Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mixed Tropical Fruit Nectars

Uploaded by

Billy Mervin StraussOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mixed Tropical Fruit Nectars

Uploaded by

Billy Mervin StraussCopyright:

Available Formats

1290

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2007, 42, 12901296

Original article Mixed tropical fruit nectars with added energy components

M. de Souza Filho,2 Paulo H. M. de Sousa,1* Geraldo A. Maia,1 Henriette M. C. de Azeredo,2 Men de Sa 2 1 Deborah dos S. Garruti & Claisa A. S. de Freitas

, Av. Mister Hull, n 2977, Campus do Pici, C.P. 12168, Fortaleza1 Departamento de Tecnologia de Alimentos, Universidade Federal do Ceara CE, CEP 60356-000, Brazil 2 Embrapa Agroindu stria Tropical, Rua Dra. Sara Mesquita, 2270, Bairro Planalto Pici, C.P. 3761, Fortaleza-CE, CEP 60511-110, Brazil (Received 26 October 2005; Accepted in revised form 2 March 2006)

Summary

The purpose of this work was to develop energy drinks from mixed tropical fruit nectars with added caeine or guarana. The nectars were formulated from puree blends, consisting of cashew apple, acerola, papaya, passion fruit and guava. Firstly, a mixture design was carried out by varying the puree proportions, in order to establish the most accepted formulation of the mixed nectar. Higher proportions of guava and papaya purees resulted in better acceptance scores, while passion fruit puree impaired the product acceptance. The most accepted formulation was that with the following puree contents: passion fruit, 3.9%; papaya, 5.7%; guava, 5.7%; and acerola, 5.7%. This formulation was dened as the control for the dierence-from-control sensory tests, conducted to compare the control added with energy components (guarana or caeine) with the control itself. Although both energy drinks were signicantly dierent from the control, they were well accepted, indicating their potential for being commercialised.

caeine, energy components, fruit puree, guarana, mixed tropical fruit, mixture design.

Keywords

Introduction

The consumers have been increasingly searching for food products that combine sensory and nutritional quality. The functional, health-promoting properties have also received major interest. One of the most important classes of functional compounds is the one of antioxidants, such as phenolic compounds, carotenoids and ascorbic acid. These compounds are involved in reducing the so-called oxidative stress in the human body. Fruits and their products are usually well accepted by the consumers, and are important sources of nutrients and antioxidant compounds. Brazil produced about 33 millions of tons of fruits in 2003, in a total area of 2.4 millions of hectares. It is one of the largest fruit producers in the world, surpassed only by China and India (FAO, 2004). The production of fruit juices and purees has continually increased. Silva (1999) estimated that the food products whose production growth rates were the highest between 1993 and 1999 were papaya, mango, acerola and guava purees and pineapple, passion fruit and cashew apple juices. In Brazil, Europe and China, there is an increasing consumption of fruit juices, nectars and other fruit beverages. In Brazil, the production volume of these

*Correspondent: Fax: 558533669751; e-mail: phmachado@vicosa.ufv.br

beverages increased by 7.5% in 2003, when the sales reached 192 millions of litres (Bouc as, 2004). Currently, there is an increasing market demand for beverages formulated from fruit blends, especially from tropical fruits (Branco & Gasparetto, 2003). Such products can be gasied or not, with variable fruit juice contents. The mixed fruit beverages present a number of advantages, such as the possibility of combining dierent avours, nutrients and functional compounds (Matsuura et al., 2004). Matsuura & Rolim (2002) obtained a mixed beverage from pineapple and acerola juices, with vefold the vitamin C content of pineapple juice alone. Salomon et al. (1977) and Mostafa et al. (1997) registered high acceptance of papayapassion fruit and papayamango mixed nectars, respectively. The addition of energy components (such as caeine) to fruit beverages has also been an important tendency. Caeine is well known by its stimulating eect on central nervous system. Guarana extracts may be used as a source of this compound (Espinola et al., 1995). Tropical fruits are widely accepted by consumers, and important sources of antioxidant compounds. Acerola (Malpighia emarginata D.C.), known to have high vitamin C levels, is also rich in anthocyanins and carotenoids, antioxidant pigments whose combination is responsible for the fruit red colour (Lima et al., 2005). Guava, mango and papaya contain considerable levels of phenolic compounds and carotenoids (Steinmetz &

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.01318.x

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Institute of Food Science and Technology Trust Fund

Mixed tropical fruit nectars P. H. M. de Sousa et al.

1291

Potter, 1996; Nguyen & Schwartz, 1999; LuximonRamma et al., 2003). Cashew apple are rich in vitamin C, carotenoids and phenolic compounds (Assunc a o & Mercadante, 2003; Kubo et al., 2006). However, most tropical fruits are highly perishable, and their postharvest losses are of major concern in tropical countries. Losses can be reduced by processing the fruits into a variety of products, such as juices or nectars. Cashew apple culture has an especial socioeconomic role in north-east Brazil. Cashew nuts are its most valuable product, while the cashew apples are sometimes treated as a residue and widely wasted. The main form of utilisation of cashew apples is to process them into juice, but its high astringency tends to impair its acceptance. The formulation of mixed fruits and nectars may be an ecient way of reducing the negative impact caused by the cashew apple astringency. The purposes of this work were to optimise the formulation of mixed tropical fruit nectar, and to evaluate its applicability as a base-formulation to develop energy drinks, by addition of guarana extract or caeine.

Materials and methods

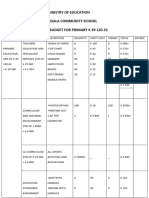

Table 1 Compositions of the mixed fruit nectars Puree proportions (%) Treatment 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Cashew apple 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 Passion fruit 7.00 3.50 3.50 3.50 5.25 5.25 5.25 3.50 3.50 3.50 5.70 3.90 3.90 3.90 4.40 Papaya 3.50 7.00 3.50 3.50 5.25 3.50 3.50 5.25 5.25 3.50 3.90 5.70 3.90 3.90 4.40 Guava 5.25 5.25 8.75 5.25 5.25 7.00 5.25 7.00 5.25 7.00 5.70 5.70 7.4 5.70 6.10 Acerola 5.25 5.25 5.25 8.75 5.25 5.25 7.00 5.25 7.00 7.00 5.70 5.70 5.70 7.50 6.10

Formulations of mixed nectars

Pasteurised and frozen cashew apple, acerola, passion fruit, papaya and guava purees were used. The purees were characterised in terms of: soluble solid contents, measured by a PR-101 digital refractometer (Atago, Norfolk, VA, USA); pH, by a HI 9321 pHmeter (Hanna Instruments, Villafranca, Padovana, Italy); and total titratable acidity (TTA) (Association of Ocial Analytical Chemists, 1995). The formulations were composed by 35% puree blend, 10% sucrose and 55% water. The puree blend consisted of cashew apple, acerola, passion fruit, papaya and guava purees. Cashew apple puree had its content xed in 14%, determined by preliminary tests as the maximum content which did not impair the acceptance of the mixed nectar. The proportions of the other purees were dened from preliminary tests. The compositions of the dierent nectar formulations, presented in Table 1, were determined according to a mixture design (Barros Neto et al., 1995).

Physicochemical and sensory analyses

per sessions. The panelists received 30 mL of each sample at 1618 C, in glasses codied with three-digit numbers. The presentation order of the samples was balanced (MacFie et al., 1989). The overall acceptance was evaluated by using a nine-point structured hedonic scale (1 dislike extremely to 9 like extremely) (Peryam & Pilgrim, 1957). In the same score sheet were included just right scales (Meilgaard et al., 1987) for assessment of the following individual attributes: bory, sweetness and acidity, in which the medium point (4) corresponded to ideal for each attribute.

Analyses of results

The software Statistica (Statsoft, 1995) was used to analyse results. For each physicochemical or sensory attribute, a model was tted from the analytical results. The models were analysed in terms of their signicance (by F-test) and determination coecient (R2). The contour plots were used as a tool to analyse the behaviour of the experimental responses as functions of the proportions of purees, as well as to determine the most accepted by the consumers.

Formulation and sensory analyses of energy drinks

The formulations resulting from all treatments were submitted to sensory and physicochemical tests. The physicochemical analyses were the following: pH, total soluble solids (TSS) and TTA. For the sensory analysis, thirty-two panelists were enlisted as suggest by Stone & Sidel (1993) in laboratory test. The tests were conducted in individual booths, under white light (daylight), and the samples were presented monadically, three samples

The most accepted formulation was submitted to a more detailed characterisation, in terms of: pH; TSS; TTA; reducing and non-reducing sugars (Miller, 1959; Instituto Adolfo Lutz, 1985) and vitamin C (Pearson, 1976). This formulation, which will be further called baseformulation, was used to elaborate the energy drinks. Synthetic caeine (Vetec, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) or guarana extract with 0.98% caeine (Duas Rodas do Sul, Brazil) were added to the Aromas, Jargua base-formulation in order to obtain a nal caeine

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Institute of Food Science and Technology Trust Fund

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2007

1292

Mixed tropical fruit nectars P. H. M. de Sousa et al.

concentration of 100 mg L)1, as used by Soares et al. (2001) in a drink formulated with cashew apple juice and guarana extract. This amount is permitted by FAO/ WHO (1997), as well as by Brazilian legislation (Brasil, 2005a), which allows a maximum caeine level of 350 mg L)1 in energy drinks. The samples were submitted to a dierence-fromcontrol sensory test. Thirty-two panelists were asked to taste the sample identied as the control (the baseformulation without energy components) and three test samples coded with random three-digit numbers (two samples with added energy components, and a third one consisting on the control sample itself the hidden control). They were asked to compare the three test samples with the control by using a scale ranging from 1 (equal to the control) to 9 (extremely dierent from the control). The results of this test were analysed by using a Dunnett test (P 0.05), in which the mean scores of the test samples were compared with that of the control. The three samples were also tested for overall acceptance, by means of a 9-point structured hedonic scale, ranging from 1 (disliked very much) to 9 (liked very much). The mean hedonic scores were compared to each other by Duncan test (P 0.05). Both Dunnett and Duncan tests were applied by using the software SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., 1999).

Results and discussion

Table 3 Means of the sensory and physicochemical determinations from the treatments Physicochemical results

Sensory results

Overall Treatments acceptance Body Sweetness Acidity pH 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 6.7 7.1 7.2 7.0 7.0 6.5 7.0 7.6 6.9 6.9 6.5 7.5 7.2 6.8 7.2 4.3 4.2 4.1 3.7 4.1 4.2 4.2 3.9 4.0 4.0 4.0 3.9 4.2 4.1 4.0 3.7 4.3 4.2 3.7 3.9 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.8 3.9 3.2 4.1 4.1 4.1 3.9 4.6 3.9 4.2 4.4 4.2 4.3 4.5 4.0 4.2 3.9 4.6 3.9 4.1 4.3 4.4 3.57 3.78 3.83 3.73 3.95 3.91 3.78 3.93 3.97 4.02 3.76 3.90 3.85 3.84 3.83

TSS TTA 12.3 12.6 12.5 12.5 12.3 12.2 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.7 10.5 12.4 13.0 13.5 13.5 0.40 0.28 0.28 0.34 0.35 0.35 0.35 0.29 0.30 0.31 0.36 0.29 0.30 0.33 0.35

TSS, total soluble solids (Brix); TTA, total titratable acidity (% citric acid).

Table 4 Regression coefcients of the models Physicochemical analyses

Sensory analyses Overall Terms acceptance Body A B C D AB AC AD BC BD CD R2 F 6.615 7.152 7.2098 6.947 0.606 )1.678 0.596 2.196 )0.330 )0.615 0.82 2.49ns 4.267 4.178 4.141 3.736 )0.801 )0.074 0.715 )1.053 0.136 0.463 0.74 1.61ns

Table 2 presents the results of the physicochemical determinations of the fruit purees, and the experimental responses are presented in Table 3. The pH, TSS and TTA total values of all the fruit purees were considered normal for the products, in accordance with the values mentioned for acerola (Vendramini & Trugo, 2000), passion fruit (De Marchi et al., 2000), guava (Lima et al., 2002), cashew apple (Akinwale, 2000) and papaya (Santana et al., 2004). The regression coecients of the models (in the normalised form), as well as F and R2 values, are presented in Table 4. All variables (puree proportions) had signicant eects on all responses, while the interactions were not signicant (P < 0.05). The model for TTA was the only signicant one. The others were considered as tendency indicators. The low signicance

Table 2 Physicochemical characterisation of the fruit purees Puree Passion fruit Guava Acerola Cashew apple Papaya pH 3.4 4.3 3.7 4.5 4.7 TSS 10.7 7.1 7.0 11.6 8.9 TTA 3.78 0.52 1.08 0.37 0.24

Sweetness Acidity pH 3.565 4.313 4.223 3.749 )0.408 )0.987 0.466 )1.092 )0.439 0.182 0.59 0.80ns 4.615 3.836 4.173 4.384 0.067 )0.059 0.362 )0.017 0.404 )1.322 0.87 3.62ns 3.587 3.805 3.841 3.749 0.804 0.517 0.213 0.192 0.567 0.640 0.76 1.78ns

TSS

TTA

11.866 0.398 12.547 0.276 12.524 0.277 12.612 0.340 )0.859 0.049 )0.546 0.052 0.589 )0.063 0.976 0.0466 1.551 )0.028 2.265 0.015 0.29 0.95 0.23ns 10.67*

A passion fruit; B papaya; C guava; D acerola. TSS, total soluble solids (Brix); TTA, total titratable acidity (% citric acid). Signicant values are shown in bolded (P 0.05). For F-values: ns, non-signicant (P > 0.05); *signicant (P 0.05).

TSS, total soluble solids (Brix); TTA, total titratable acidity (% citric acid).

of the models may be attributed to the very small variations among conditions of dierent treatments, generating small variations in responses; the models probably were not able to accurately predict the behaviour of the responses. The contour plots are presented in Figs 14. Although the body, acidity and sweetness values were near the

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2007

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Institute of Food Science and Technology Trust Fund

Mixed tropical fruit nectars P. H. M. de Sousa et al.

1293

Figure 1 Contour plots referring to total soluble solids.

Figure 2 Contour plots refering to pH.

Figure 3 Contour plots referring to total titratable acidity (%).

ideal for all treatments, some tendencies were observed (Table 3). The treatments that resulted in acidity nearer to ideal values were those containing higher contents of guava and papaya purees, that is to say, those with lower TTA (about 0.3%) and higher pH (near 4.0). The nearer ideal sweetness values occurred for the samples with higher guava and papaya contents that presented

higher TSS (above 12.5Brix). The samples with higher passion fruit puree contents were perceived by panelists as slightly more concentrated than ideal; this may be related to their higher acidity. The higher the proportions of guava and papaya puree, the higher was the acceptance. On the other hand, the passion fruit puree was the one that most impaired

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Institute of Food Science and Technology Trust Fund

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2007

1294

Mixed tropical fruit nectars P. H. M. de Sousa et al.

Figure 4 Contour plots referring to overall acceptance (1: dislike extremely to 9: like extremely).

the product acceptance. Thus, it seems that the betteraccepted samples were those with higher TSS/TTA ratio. Among the tested formulations, the highest overall acceptance was presented by the following formulation: 3.9% passion fruit, 5.7% papaya, 5.7% guava and 5.7% acerola. The characteristics of the chosen beverage were the following: pH, 3.86; TSS, 12.97Brix; TTA, 0.34%; TSS/ TTA, 38.15; reducing sugars, 11.04%; non-reducing sugars, 19.51%; vitamin C, 77.35 mg (100 mL))1. These pH, TSST and TTA values in the nal product contribute to its safety (Jay & Anderson, 2001). Even so a daily dose of 200 mL (content of the packaging used) of the formulation, the content of vitamin C provides 340% of the recommended daily intake of this vitamin, i.e. 45 mg (100 mL))1 (FAO/ WHO, 2001; Brasil, 2005b). Table 5 presents the results of the dierence-from-control test, indicating that both energy drinks were signicantly dierent from the control (P 0.05). Brazilian legislation does not prescribe a maximum daily dose for caeine, but only the maximum caeine concentration in beverages (350 mg L)1) (Brasil, 2005a), whose values are in accordance with the energy drinks obtained in this work. Table 6 presents the results of Duncan test of overall acceptance of the energy drinks and the control. The mean hedonic ratings for both energy drinks were not signicantly dierent from each other, but both were lower than the control (P 0.05). Still, their mean score was within

Table 6 Results of the difference-from-control test Sample Control Caffeine Guarana Mean overall acceptance 7.11 a 6.44 b 6.40 b

Means followed by the same letter are not signicantly different (P > 0.05).

Figure 5 Frequency histogram for overall acceptance scores.

Table 5 Results of the difference-from-control test Mean difference-from-control Hidden control Caffeine Guarana 1.97 2.81* 7.03*

Values signicantly different from the control (Dunnetts test, *P 0.05).

the acceptance range (i.e. above 5 neither liked nor disliked). Although the mean overall acceptance of both energy drinks was not signicantly dierent from each other, the histogram in Fig. 5 indicates some dierences in their frequency distributions. The frequency of scores within acceptance range was lower for the sample with added guarana extract (74.55%) than for the sample with synthetic caeine (83.64%), while the control sample was accepted by 89.09% of the panelists. The most frequent response of the control was 8 (liked much). The sample with added caffeine presented a near-normal distribution around 7

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2007

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Institute of Food Science and Technology Trust Fund

Mixed tropical fruit nectars P. H. M. de Sousa et al.

1295

(moderately liked). Although the sample with added guarana has been the least accepted one, it is interesting to notice that it was scored 9 (liked very much) by 20% of the consumers, the highest frequency for this score.

Conclusions

The formulation with 3.9% passion fruit, 5.7% papaya, 5.7% guava and 5.7% acerola was the most accepted by consumers. Although the energy drinks have been signicantly dierent from the control, both were well accepted, especially that with added synthetic caeine, which suggests that they may represent an interesting option for consumers.

Acknowledgements

This work received nancial support from MESA, cio, MCT/CNPq and FUNCAP. CT-Agronego

References

Akinwale, T.O. (2000). Cashew apple juice: its use in fortifying the nutritional quality of some tropical fruits. Europe Food Research and Technology, 211, 205207. Association of Ocial Analytical Chemists (1995). Ofcial Methods of Analysis of the AOAC, 16th edn. P. 1141. Arlington, VA: AOAC. Assunc a o, R.B. & Mercadante, A.Z. (2003). Carotenoids and ascorbic acid composition from commercial products of cashew apple (Anacardium occidentale L.). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 16, 647657. Barros Neto, B., Scarminio, I.S. & Brums, R.E. (1995). Planejamento e Otimizac a o de Experimentos. P. 299. Campinas: Editora da UNICAMP. Bouc as, C. (2004). Bebidas: Consumo de sucos prontos cresceu 11,2% em 12 meses. Jornal Valor Economico, 1, 13. Branco, I.G. & Gasparetto, C. (2003). Aplicac a o da metodologia de superf cie de resposta para o estudo do efeito da temperatura gico de misturas terna rias de sobre o comportamento reolo manga, laranja e cenoura. Ciencia e Tecnologia de Alimentos, 23, 166171. Brasil (2005a). Resoluc a o RDC no 273, de 22 de setembro de 2005. Aprova o Regulamento Tecnico para Misturas para o Preparo de Alimentos e Alimentos Prontos para o Consumo. D.O.U. Diario Ocial da Unia o; Poder Executivo, de 23 de setembro de 2005. ria. ANVISA Age ncia Nacional de Vigila ncia Sanita Brasil (2005b). Resoluc a o RDC no 269, de 22 de setembro de 2005 Aprova o Regulamento tecnico sobre a ingesta o diaria recomendada rio Ocial da (IDR) de protena, vitaminas e minerais. D.O.U. - Dia Unia o; Poder Executivo, de 23 de setembro de 2005. ANVISA ria. Age ncia Nacional de Vigila ncia Sanita De Marchi, R., Monteiro, M., Benato, E.A. & Silva, C.A.R. (2000). Uso da cor da casca como indicador de qualidade do amarelo (Passiora edulis Sims. f. avicarpa Deg.) maracuja ` industrializac destinado a a o. Ciencia e Tecnologia de Alimentos, 20, 381387. Espinola, E.B., Dias, R.F., Mattei, R. & Carlini, E.A. (1995). Pharmacological activity of Guarana (Paullinia cupana Mart.) in laboratory animals. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 55, 223229.

FAO (2004). Statistical Database. Production and trade. Available at: http://faostat.fao.org (accessed 3 February 2004). FAO/WHO (1997). Codex Alimentarius. In: Report of the Twentyfourth Session of the Codex Committee on Food Labelling (edited by A. Mackenzie). Ottawa, ON: FAO/WHO. FAO/WHO (2001). Human vitamin and mineral requirements. In: Report 7a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation (edited by G. Nantel & K. Tontisivia). Pp. xxii + 286. Bangkok: FAO/WHO. Instituto Adolfo Lutz (1985). Normas analticas do Instituto Adolfo lises de alimentos, 3rd edn. Lutz: metodos qumicos e fsicos para ana P. 533. Sa o Paulo: Instituto Adolfo Lutz. Jay, S. & Anderson, J. (2001). Fruit juice and related products. In: Spoilage of Processed Foods: Causes and Diagnosis (edited by C.J.M. Moir, C. Andrew-Kabilafkas, G. Arnold, B.M. Cox, A.D. Hocking & I. Jenson). Pp. 187197. Marrickville: Southwood Press. , T.J. & Tsujimoto, K. (2006). Antioxidant Kubo, I., Masuoka, N., Ha activity of anacardic acids. Food Chemistry, 99, 555562. Lima, M.A.C., Assis, J.S. & Gonzaga Neto, L. (2002). Caracterizac a o dos frutos de goiabeira e selec a o de cultivares na Regia o do dio Sa Subme o Francisco. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, 24, 273276. Lima, V.L.A.G., Melo, E.A., Maciel, M.I.S., Prazeres, F.G., Musser, R.S. & Lima, D.E.S. (2005). Total phenolic and carotenoid contents in acerola genotypes harvested at three ripening stages. Food Chemistry, 90, 565568. Luximon-Ramma, A., Bahorun, T. & Crozier, A. (2003). Antioxidant actions and phenolic and vitamin C contents of common Mauritian exotic fruits. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 83, 496 502. MacFie, H.J., Bratchell, N., Greenho, K. & Vallis, I.V. (1989). Designs to balance the eect of order of presentation and rstorder carry-over eects in hall tests. Journal Sensory Studies, 4, 129148. Matsuura, F.C.A.U. & Rolim, R.B. (2002). Avaliac a a o da adic o de ` produc suco de acerola em suco de abacaxi visando a a o de um blend com alto teor de vitamina C. Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, 24, 138141. Matsuura, F.C.A.U., Folegatti, M.I. da S., Cardoso, R.L. & Ferreira, D.C. (2004). Sensory acceptance of mixed nectar of papaya, passion fruit and acerola. Scientia Agricola, 61, 604608. Meilgaard, M., Civille, G.V. & Carr, B.T. (1987). Sensory Evaluation Techniques. P. 279. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. Miller, G.L. (1959). Use of dinitrosalicycle acid reagent for determination of reducing sugars. Analytical Chemistry, 31, 226248. Mostafa, G.A., Abd-El-Hady, E.A. & Askar, A. (1997). Preparation of papaya and mango nectar blends. Fruit Processing, 7, 180185. Nguyen, M.L. & Schwartz, S.J. (1999). Lycopene: chemical and biological properties. Food Technology, 53, 3845. Pearson, D. (1976). Tecnicas de laboratorio para el analises de alimentos. P. 331. Zaragoza: Editorial Acribia. Peryam, D.R. & Pilgrim, P.J. (1957). Hedonic scale method for measuring food preferences. Food Technology, 11, 914. Salomon, E.A.G., Kato, K., Martin, Z.J., Silva, S.D. & Mori, E.E.M. ctar de papaya (1977). Estudo das composic o es (blending) do ne passion fruit. Boletim do Instituto de Tecnologia de Alimentos, 51, 165179. Santana, L.R.R., Matsuura, F.C.A.U. & Cardoso, R.L. (2004). tipos melhorados de mama Geno a o (Carica papaya L.): avaliac o sensorial e f sico-qu mica dos frutos. Ciencia e Tecnologia de Alimentos, 24, 217222. SAS Institute, Inc. (1999). SAS Users Guide: Statistics, Version 4.10, Edition. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc. Silva, E.M.F. (1999). Estudo sobre o mercado de frutas. Sa o Paulo: FIPE. Soares, L.C., Oliveira, G.S.F., Maia, G.A., Monteiro, J.C.S. & Silva Jr, A. (2001). Obtenc a o de bebida a partir de suco de cashew apple (Anacardium occidentale, L.) e extrato de guarana (Paullinia cupana sorbilis Mart. Ducke). Revista Brasileira de Fruticultura, 23, 387390.

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Institute of Food Science and Technology Trust Fund

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2007

1296

Mixed tropical fruit nectars P. H. M. de Sousa et al.

Statsoft (1995). Statistica for Windows [Computer Program Manual]. Tulsa, OK: StatSoft. Steinmetz, K.A. & Potter, J.D. (1996). Vegetables, fruit, and cancer prevention a review. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 96, 10271039.

Stone, H. & Sidel, J.L. (1993). Sensory Evaluation Practices. P. 338. New York, NY: Academic Press. Vendramini, A.L. & Trugo, L.C. (2000). Chemical composition of acerola fruit (Malpighia punicifolia L.) at three stages of maturity. Food Chemistry, 71, 195198.

International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2007

2007 The Authors. Journal compilation 2007 Institute of Food Science and Technology Trust Fund

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Remuneration Is Defined As Payment or Compensation Received For Services or Employment andDocument3 pagesRemuneration Is Defined As Payment or Compensation Received For Services or Employment andWitty BlinkzNo ratings yet

- ABB Price Book 524Document1 pageABB Price Book 524EliasNo ratings yet

- DT2 (80 82)Document18 pagesDT2 (80 82)Anonymous jbeHFUNo ratings yet

- White Button Mushroom Cultivation ManualDocument8 pagesWhite Button Mushroom Cultivation ManualKhurram Ismail100% (4)

- Windsor Machines LimitedDocument12 pagesWindsor Machines LimitedAlaina LongNo ratings yet

- Process Interactions PDFDocument1 pageProcess Interactions PDFXionNo ratings yet

- Epenisa 2Document9 pagesEpenisa 2api-316852165100% (1)

- Hitt PPT 12e ch08-SMDocument32 pagesHitt PPT 12e ch08-SMHananie NanieNo ratings yet

- Purchases + Carriage Inwards + Other Expenses Incurred On Purchase of Materials - Closing Inventory of MaterialsDocument4 pagesPurchases + Carriage Inwards + Other Expenses Incurred On Purchase of Materials - Closing Inventory of MaterialsSiva SankariNo ratings yet

- Question Bank For Vlsi LabDocument4 pagesQuestion Bank For Vlsi LabSav ThaNo ratings yet

- QuizDocument11 pagesQuizDanica RamosNo ratings yet

- CEA 4.0 2022 - Current Draft AgendaDocument10 pagesCEA 4.0 2022 - Current Draft AgendaThi TranNo ratings yet

- Fr-E700 Instruction Manual (Basic)Document155 pagesFr-E700 Instruction Manual (Basic)DeTiEnamoradoNo ratings yet

- Relevant Cost For Decision: Kelompok 2Document78 pagesRelevant Cost For Decision: Kelompok 2prames tiNo ratings yet

- Labor CasesDocument47 pagesLabor CasesAnna Marie DayanghirangNo ratings yet

- Residential BuildingDocument5 pagesResidential Buildingkamaldeep singhNo ratings yet

- CY8 C95 X 0 ADocument32 pagesCY8 C95 X 0 AAnonymous 60esBJZIj100% (1)

- Quantity DiscountDocument22 pagesQuantity Discountkevin royNo ratings yet

- PanasonicDocument35 pagesPanasonicAsif Shaikh0% (1)

- FBW Manual-Jan 2012-Revised and Corrected CS2Document68 pagesFBW Manual-Jan 2012-Revised and Corrected CS2Dinesh CandassamyNo ratings yet

- Sign Language To Speech ConversionDocument6 pagesSign Language To Speech ConversionGokul RajaNo ratings yet

- Te 1569 Web PDFDocument272 pagesTe 1569 Web PDFdavid19890109No ratings yet

- Dynamics of Interest Rate and Equity VolatilityDocument9 pagesDynamics of Interest Rate and Equity VolatilityZhenhuan SongNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Education Musala SCHDocument5 pagesMinistry of Education Musala SCHlaonimosesNo ratings yet

- SDFGHJKL ÑDocument2 pagesSDFGHJKL ÑAlexis CaluñaNo ratings yet

- Economies and Diseconomies of ScaleDocument7 pagesEconomies and Diseconomies of Scale2154 taibakhatunNo ratings yet

- Department of Labor: 2nd Injury FundDocument140 pagesDepartment of Labor: 2nd Injury FundUSA_DepartmentOfLabor100% (1)

- In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements For The Award of The Degree ofDocument66 pagesIn Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements For The Award of The Degree ofcicil josyNo ratings yet

- Estimation and Detection Theory by Don H. JohnsonDocument214 pagesEstimation and Detection Theory by Don H. JohnsonPraveen Chandran C RNo ratings yet

- The Role of OrganisationDocument9 pagesThe Role of OrganisationMadhury MosharrofNo ratings yet