Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alves Ritos de Iniciacion PDF

Uploaded by

LauraZapataOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alves Ritos de Iniciacion PDF

Uploaded by

LauraZapataCopyright:

Available Formats

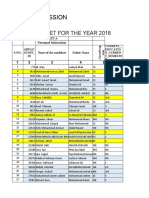

Transgressions and Transformations: Initiation Rites among Urban Portuguese Boys Author(s): Julio Alves Source: American Anthropologist,

New Series, Vol. 95, No. 4 (Dec., 1993), pp. 894-928 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of the American Anthropological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/683023 Accessed: 10/06/2010 09:35

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Blackwell Publishing and American Anthropological Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Anthropologist.

http://www.jstor.org

JULIO AIVES

SmithCollege

and Transformations: Rites Initiation Transgressions amongUrbanPortugueseBoys

In the absence of institutionalized, initiation ritesin thecommunity of Ajuda adult-guided old boysconstructed in Lisbon,Portugal,nine-and ten-year theirownritesin thepeergroup. Theseritesconsisted thecommunity and narrative of a combination of rampages throughout aboutthoseexperiences in thepeer and thenarratives performances group.Boththerampages exhibit associated with ritesof passage.This articleappliestraditional featurestraditionally conceptsin novel ways that may prove promising in studying initiation rites in other urbansocieties. Western, contemporary,

COMMUNITYOF AJUDA in Lisbon, Portugal, which I studied from TN THEWORKING-CLASS November 1986 to June 1987, there were no institutionalized, adult-guided initiation rites. However, nine- and ten-year-old boys constructed their own initiation rites in the peer group, rites that displayed features usually associated with traditional rites of passage. These rites consisted of rampages throughout the community (solo or with peers) and subsequent public narrativization of these experiences before peers. Rampage narratives occurred in any number of public settings (the school yard, the playground, the street) where there was an audience of peers. The two narratives discussed in this article (included in full in Appendixes A and B) were told by two nine-year-old boys, Bernardo and Ernesto, one wintry Monday afternoon (February 2, 1987) in the former cafeteria of their school. The school no longer served hot meals and the former cafeteria was nothing but a big room with a few tables and chairs that was used for play and special projects. The boys attended school only in the morning, and in the afternoon, weather permitting, they often played in the school yard and the street in front of the school. On cold and rainy days, like the one on which the two narratives discussed here were collected, play moved indoors into the former cafeteria. Present in the room the day these two narrativeswere collected were myself, Bernardo, Ernesto, and three other boys. By the time I collected these narratives,I had been part of the boys' life in the school, the school yard, the playground, and the street for over three months, during which time I got to know the boys well, conducted observations of their verbal and nonverbal interaction in a variety of locales, and had the opportunity to talk with community members about the boys and other matters. Rampage narratives were performed regularly in the peer group by nine- and ten-year-old boys. Once introduced, these narratives often generated other narratives of the same type, as was the case when the two narratives discussed here were collected. The storytelling events could turn into a kind of competition for the best story. Those boys (like Ernesto) who successfully underwent rampages and were highly skilled performers of rampage narratives had power and status in the peer group; they were considered more manly than the majority of the boys.1In some ways, the performances of rampage narratives in the peer group were more important initiation rites than the rampage experiences themselves, because the experiences, unlike the narratives, were usually beyond the scrutiny of the peer group. In other words, within the context of the American 95(4):894-928. Copyright ? 1993, American Anthropological Association. Anthropologist

894

Alves]

ANDTRANSFORMATIONS TRANSGRESSIONS

895

storytelling events, the narrative performances were more real than the experiences: it that accorded storytellers more manly status in the peer was the narrativeperformances group. The narratives and the actual experiences are very much two sides of the same coin, however, and should be discussed together; the boundary between narrative and experience is not alwayseasily discernable. Van Gennep and Turner on Rites of Passage In an early, groundbreaking work, van Gennep (1960[1909]) argued that the life cycles of individuals and collectives can best be understood as the crossing of a series of ritual thresholds. In his words, "lifeitself means to separate and to be reunited, to change form and condition, to die and to be reborn. It is to act and to cease, to wait and rest, and then to begin again, but in a different way" (p. 189). From birth to death, human beings everywhere are positioned in various social states, "synchronically and in succession," said van Gennep. Periodic transitions from one state to another involve changes in social status and are alwaystimes of social and emotional crisis for those undergoing the changes. Ritual ceremonies aid in incorporating individuals into their new statuses in the group. These ceremonies may differ in form, depending on the particular culture and event, but they all have the similar function of aiding individuals in passing from one well-defined state to another. It is these ceremonies that van Gennep originally called ritesdepassage,or rites of passage.2 Rites of passage, then, are ceremonies that occur at times of transition (crisis) in individuals' social and cultural lives. Specifically, events such as birth, initiation rites (social puberty), betrothal, marriage, advancement to a higher class, or funerals are but a sample of times of transition in the lives of human beings across cultures; of course, the particular times of transition deemed critical across cultures vary. For van Gennep, the full schema of a rite of passage comprises three major phases: (1) preliminal rites (rites of separation), (2) liminal (or threshold) rites (rites of transition), and (3) postliminal rites (rites of incorporation). Each of these phases is, however, not developed to the same degree in every ceremonial pattern, even within the same culture. For example, rites of separation may be emphasized in funeral ceremonies, whereas rites of transition may be an important part of initiation, betrothal, and pregnancy ceremonies, but be minimized in adoption, birth of a second child, or remarriage ceremonies. Rites of incorporation may be prominent in marriage ceremonies. Turner (especially 1967, 1969, and 1974a) developed van Gennep's argument specifically in terms of initiationrites,rites of social puberty.3Turner (1974a:298) elaborated the thesis that "a man is both a structural and an anti-structural entity, who 'grows' Turner said, is "all through anti-structure and 'conserves' through structure." Structure, that holds people apart, defines their differences, and constrains their actions" (p. 47). However, structure does not characterize all social activity. Turner used van Gennep's term liminality to describe the domains of antistructure, which he defined as "any condition outside or on the peripheries of everyday life" (p. 47). Times of transition between well-defined, fixed states dominated by socialstructure (everyday life) are always liminal; that is, they are alwaystemporally, spatially,and socially "ambiguous, unsettled, and unsettling" (p. 274). Turner (1974b) described such periods as "social limbo." Out of these periods of liminality, a state of what Turner called communitas emerges. In Turner's framework, communitasis a vague and elusive term that is defined extensively in contrast to structure. Both communitas and structure are social modalities. Communitas is brought about during liminal periods by ritual trials, ritual strippings of preliminal status, and ritual humiliation. It liberates individuals from the constraints of conformity to social norms imposed by structure. Itis "adirect, immediate and total confrontation of human identities" (Turner 1969:132; 1974a:49). In a very brief and impressionistic manner, the opposition between the experiences of communitas and structure might be outlined as follows:

896

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

Communitas Nature Freedom Spontaneous Direct and immediate Concrete Undifferentiated Nonrational Liberating Egalitarian

Structure Culture Law Controlled Circumstantial and removed Abstract Differentiated Rational Confining Hierarchical

It is important not to confuse structure and social structure, for both communitas and structure are part of social structure, part of a person's overall (contrasting) social experience. As Turner (1974a:274) made clear, "communitas does not merge identities; it liberates them from conformity to general norms, though [and this is important] this is necessarily a transient condition if society is to continue to operate in an orderly fashion." Traditionally, anthropologists have studied preindustrial, highly religious cultures in which stages of physiological and social maturation tend to be overtly accompanied by religious (highly ritualized) ceremonies; for example, initiation ceremonies in these cultures might involve mutilation rites (such as circumcision) as a means of symbolizing permanent differentiation (a rite of separation). Generally, however, initiation rites exist in all societies in varying degrees. Turner (1967:93) argued that "rites depassageare found in all societies but tend to reach their maximal expression in small-scale, relatively stable and cyclical societies, where change is bound up with biological and meteorological rhythms and recurrences." Gilmore (1987) and others (see Gilmore 1987:15 for details and references) have noted, however, that Mediterranean societies (urban and rural) are particularly lacking in institutionalized, adult-guided initiation rites. In general (there are exceptions), becoming a man in the Mediterranean is an individual enterprise. Boys have to find their own ways to demonstrate their manhood, because there is pressure on them to do so even though formal rites are minimal or nonexistent. In Gilmore's words, "in the resultant absence of a clear-cut consensual rupture with femininity, and without biological markers like menarche to signal manhood, each individual must prove himself in his own way" (1987:15). My research supports Turner's (1967:93) claim that "ritesdepassageare found in all societies" and Douglas's (1966, 1970) point that everydaylife in contemporary, Western, urban societies is full of common symbols and everyday rites, including initiation rites, that we do not recognize (frame) as such. Indeed, "there is no evidence that a secularized urban world has lessened the need for ritualized expressions of an individual's transition from one status to another" (Kimball 1960:XVII). As Douglas (1966:68) convincingly showed, an activity as mundane as spring cleaning, for example, can be construed as a rite of separation and renewal. However, there are obvious, important differences between initiation rites in preindustrial societies and those in a contemporary, Western, urban society like Ajuda. In Ajuda, initiation rites were not formal and institutionalized, and the novices (those undergoing the rites, also known as candidates, initiands, or neophytes) were not guided through the rites by elders (also known as instructors or shamans). This lack of adult guidance had repercussions for the organization of initiation rites: the rites became exclusively peer-group centered. Coon's comments about contemporary American culture apply also to Ajuda:

Unlike the children of hunters, the boys and girls [nowadays] have no adults to guide them through the puberty ordeals that they need in order to maintain social continuity. It is no wonder that they create age-graded micro-societies of their own. The secrecy that once formed

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS

897

to their parents,to whom they will not revealwhat a vital partof pubertyrites is transferred theyhavebeen doing. [1971:392] The Rampage: Initiation Rites in Ajuda In Ajuda, preadult stages of social maturation were intimately connected with schooling. There were three primary stages of social development for boys. As predicted by van Gennep (1960[ 1909] ), all three stages entailed not only a change in social position, but also a change in territorial (spatial) domains. The three stages were as follows: Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Early childhood Late childhood Adolescence app. 0-05 years old app. 6-10 years old app. 11-18 years old

Each of these stages manifested a different Discourse.4 A child spent early childhood (stage 1) with a primary caretaker (usually the mother) and siblings within the confines of the home (spatially, the house and the backyard). The child was not allowed to go out unattended. The beginning of late childhood (stage 2) was marked by the beginning of schooling and, for boys, a move out into the street. Boys then spent most of their time either at a local elementary school or playing with their peers in the street.5 They explored different areas of their immediate environment together, unescorted by a caretaker. Adolescence (stage 3) was marked by the end of primary schooling (at a local school) and the beginning of secondary schooling in a different neighborhood. In this stage, boys explored their own neighborhoods thoroughly and began exploring neighborhoods beyond their own, ultimately, the entire city and beyond. In this article, I focus on the transition between late childhood (stage 2) and adolescence (stage 3). In terms of Discourses, I analyze the transition from the Discourse of the male child to that of the male adolescent. In general, the male Discourse became increasingly gendered and dominant over time. As noted above, however, there were no formal, institutionalized, adult-guided initiation rites in Ajuda. In the absence of these, nine- and ten-year-old boys in Ajuda created their own initiation rites by themselves and/or with their peers; this supports Gilmore's (1987) claim that initiation rites in the Mediterranean are an individual enterprise to a great extent. The boys went out into the community on their own or in small groups and ran wildly, seemingly without a purpose (other than for the sake of running itself), through other people's backyards, creating damage as they went along and exposing themselves to danger. Such antisocial behavior is expected during liminal periods, when "the young people can steal and pillage at will or feed and adorn themselves at the expense of the community" (van Gennep 1960[1909]:114) and "profane social relations may be discontinued, former rights and obligations suspended, the social order may seem to have been turned upside down" (Turner 1974b:59). Douglas (1966), too, argued that antisocial behavior is an appropriate way to express one's marginal condition during liminal periods. The rampages were subsequently followed by long, involved narrative accounts in the peer group. The rampages and the narrative performances worked in tandem as an initiation rite in the peer group. The narratives were a crucial aspect of the rampages because, in the absence of adults who could publicly declare the meanings of specific experiences, they were the only means boys had to invest the rampages with appropriate meanings in a public forum. Also, as noted earlier, because the boys often underwent rampages on their own or with a small group of friends, the narrative performances were a means for them to make their experiences known to the wider peer group. The rampages and their narrative accounts were rites accompanying a critical transition period in the construction of an increasingly well-defined, gendered male Discourse. Consequently, they reflected a state of communitas.

898

ANTHROPOLOGIST AMERICAN

[95, 1993

Turner(e.g., 1967, 1974b) noted that during the liminal periods of initiation rites, a stateof communitas is brought about by a series of ritual trials, ritual stripping of any signsof preliminal status, and ritual humiliation. Initiation into the various stages of manhood is usually a difficult process for novices. As Gilmore (1990:11) noted, "real manhood [across cultures] is different from simple anatomical maleness ... it is not a naturalcondition that comes about spontaneously through biological maturation but ratheris a precarious or artificial state that boys must win against powerful odds." The rampagenarratives of boys in Ajuda reveal a number of ritual trials, especially in the formof confrontations with dangerous situations, peers, and even adults. In all cases, boyshad to show courage by holding their ground and standing by their convictions. Participationin the ritual trials of the rampage was compulsory if a boy wanted to increasehis power and status within the peer group. (Across cultures, participation in initiation rites is also a compulsory, nonvoluntary activity; cf. Gilmore 1990.) The rampagewas exciting and empowering for the boys, but it was also frightening. Boys whowere afraid to participate in rampages risked being accused of childishness and/or effeminacy (accusations that would have greatly diminished their power and status in the peer group), so they usually had excuses ready as to why they did not participate, suchas Bernardo's: 1:B(A):6

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 eu tava la num dia Iwas there one day a brincar corn o meu irmao nas ferias grandes playingwith my brother during summer vacation eramos uns tropas que andavamos a correr pelos quintais wewere soldiers who were running through backyards ia ia tum tum (sound effects) e o meu irmao and my brother eu tinha que ir nessedia ao medico I had to go to thedoctorthat day e fui-meembora andwent away tomeibanho I tooka bath

Sometimes, however, boys were struck by fear on the spot and simply refused to participate, or quit halfway through if the rampage was already underway. In the following excerpt from Ernesto's narrative, Bernardo quit halfway through: 2:E(B):

48 49 50 fomos a andar fomos a andar we walked we walked ate que chegamos a um beco sem sa/da until we got to a dead end "olha agora so podemos sair por este quintal" "look now we can only go out through this backyard"

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS

899

51

era o Nardo assim and Nardo went like this "ai nao por ai nao saio "oh no I'm not going out through there ta ai um velho there's an old man there ha ai um velho there's an old man there vou mas e vou mas e dar a volta what I'm going to do what I'm going to do is go around e ainda aparece ai com um sacho ou com uma vassoura and he might well show up there with a weeding hoe or a broom ficamos sem cabeta" we'll lose our heads"

52 53 54 55 56 57

Ernesto went on to tease Bernardo for having lost his nerve, and implied that he'd acted like a girl. In relating Bernardo's alleged excuse as direct discourse (lines 52-57), Ernesto was teasing his friend (who was one of the boys present at this performance) by projecting on him the values of the domestic realm (safety, caution, fear) and simultaneously glorifying himself by implicitly disavowing those values for himself. Instead he claimed for himself one of the quintessential value of the public realm: courage. Later in the narrative, when Ernesto returned to Bernardo, who had stayed behind, and told him of his adventures, Ernesto again teased his friend. Ernesto reported the following interchange between the two, beginning with Bernardo's response: 3:E(B): 114 B: "ah ah iii porque e que tu nao me disseste? "ah ah heee why didn't you tell me? 115 porque?" why?"

116 E: "eujfaestava a espera" "Iwas waiting for that" 117 B: "tu e que tens tanta sorte" "you'rejust very lucky" 118 E: "a culpa foi tua por nao vires comigo" "it was your fault for not having come with me" 119 acabou it ended

Ernesto deemed Bernardo's behavior cowardly and Bernardo was publicly teased for it in the narrative performance. During the rampage, caution was a weakness and a sign of childishness and effeminacy. Such behavior was teased. Bernardo missed out on the excitement of roaming through the neighborhood and exposing himself to all sorts of danger because he did not have courage. Bernardo tried to defend himself by pinning the incident on luck (line 117). Ernesto contradicted him, however. He was ready with an answer, because, as he said, he "was waiting for that [the excuse]" (lines 116 and

900

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

118).Emesto countered that it was Bernardo's "fault"(line 118), the "fault"being that Bernardodid not show more courage and gowith him in the first place. Such teasing is not uncommon during initiation rites.Turner (1974a) discussed similar practices of ritual humiliation during initiation rites. Actually, it is one means of bringingabout a state of communitas. Gilmore (1990:12-14) also noted that, in many cultures,including Greek Aegean culture (Bernard 1967), boys who are not unwaveringlycourageous and show signs of weakness during oftentimes brutal initiation rites arescorned and accused of childishness and effeminacy. Ernesto's teasing of Bernardo was friendly and not mean-spirited, but the message was clear nonetheless. Likethe rampageexperiences, the performances of the rampagenarratives in the peer group were a kind of trial for the boys performing, because in performing their rampagenarratives, boys publicly exposed themselves to the scrutiny and judgment of theirpeers. Also like the rampage experiences, the performances were compulsory if a boywanted to enhance his power and status in the peer group; undergoing rampages on one's own was not sufficient to enhance one's power and status in the peer group. The fact that the teasing/humiliation that happened between Ernesto and Bernardo at thetime of the rampage happened again during Ernesto's performance of his narrative (witha new audience) further exemplifies the interconnection between narrative and experience. Such interconnections between narrative and experience conflate absolute distinctions between the two with regard to initiation rites in Ajuda and often make it difficult to discern between the two. RitualTrials and Temporary Insanity To be judged mature by their peers and acquire power and status in the peer group, boys in Ajuda confronted and overcame "powerful odds" (Gilmore 1990) in the form of dangerous physical trials, often cast in military terms. Boys performed rampage narrativesto show their peers that they (the boys) possessed the prestigious qualities of the male Discourse: courage, autonomy, bravery, fearlessness, assertiveness, toughness, resolve. Again, the performances of rampage narratives were particularly important in the context of initiation rites because these performances were boys' main opportunity to present their newly constructed, adultlike Discourses to their peers; it was through these performances that they showed their peers that they were good at being men (to borrow a phrase from Herzfeld 1985:16). In other words, boys asserted their own manhood in the peer group extensively through public performances of rampage narratives.Similar celebrations of manhood through oral narrative performances have been documented for other cultures. For example, in eastern Morocco, the heroic, brave feats of "true"men are celebrated in songs at festivals (Marcus 1987); in Crete, men sing about their own (and their ancestors') virility-including the heroic, brave feats of both-in coffee shops (Herzfeld 1985). Boys went to great lengths in their narratives to show the harshness of their trials during the rampages, and often they even claimed to have purposefully aggravated the trials to intensify their efficacy. Here is Ernesto, speaking of one such trial (ignore the column on the right for now): 4:E(B):

9 10 11 andamosa subir arvores we went around climbing trees pedras a cair rocks falling eramos uns aventureiros we were adventurers preterit perfect no inflected verb preterit imperfect

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS ANDTRANSFORMATIONS

901

12

e depois anddmos por ervas and then we walked through weeds os sapatos cheios de lama sujavamos we would get our shoes really muddy

pra escorregarmosmais

preterit imperfect preterit imperfect

personal infinitive

13

14

so that we slip more 15 e pra termos mais frio and so that we feel colder e subiamos grandes mon/ and we would climb high moun/ grandes subidas assim em pedra big ramps like of stone que se a gente por acaso caisse that if we happened to fall by chance

eramos capaz de partir duas pernas we could well break two legs

personal infinitive

16 17 18

preterit imperfect no inflected verb

preterit imperfect of the subjunctive mood preterit imperfect no inflected verb

19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

e e a cabeca e dois bracos and and the head and two arms

ficavamos a quase paralfticos

we would become practically paralyzed todos embrulhados em ligaduras all wrapped up in bandages mas por sorte nada disso aconteceu but luckily nothing like that happened eu desta vez desta vez desta vez this time this time this time I desta vez eu erao o chefe this time I was the the leader erao comandante Iwas the commandant e eu e e eu e que ia tripular este treino and I and and I was the one who was going to navigate this training session subi uma rampinha I went up a small ramp

cheia de pedras a cairem

preterit imperfect no inflected verb

preterit perfect no inflected verb

preterit imperfect preterit imperfect simple present, preterit imperfect preterit perfect future imperfect of the subjunctive mood preterit perfect

28

29

full of falling rocks 30 pus-me de pe I stood up

902

ANTHROPOLOGIST AMERICAN

[95, 1993

31

olhei pra baixo

down looked 32 33 34 35 36 37 e eraeu assim pra mim I went like this to myself and "ai meu Deus "oh my God ainda bem que nao tenhovertigens I'm glad I don't get dizzy spells trambolhao" se naoja tava a dar um or I'dbe falling right now" depois andamos we went then andamosa rastejar pela relva went crawling through the grass we

quando fomos a ver

perfect preterit imperfect preterit inflected verb no

present simple

preterit imperfect perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit imperfect preterit

38

we took a look when

39

todos verdes por causa da erva estdvamos all were we green because of the grass

trials. Similar Lines13-15 speak specifically to the intensification of already difficult also been has bravery extra show to rites initiation during intensification of trials Island in Truk on documented for other, radically different cultures. For example, of manqualities desirable highly Micronesia, young men show strength and courage, motorsmall in trips open-ocean long-distance, hood, by participating in dangerous, boats.Marshall (1979:59) wrote: often undertake boats are much less seaworthy than the sailing canoes, and young men These but liquid aboard nothing and sails, or oars no motor, single a fuel, limited voyages with such other risky Several bravery. show to craft... refreshments. .., risking the open sea in a small bravery on exhibiting for A way men.... Trukese young occupy endeavors ordangerous sharks is to spearfish in the deepwater passes and areas outside the reef where large Piis-Losap common. [Quoted in Gilmore 1990:72] are acts of bravery The Trukese constantly reaffirm their manhood by displaying aggressive the principles but different, are in a public forum. The details of these two situations are similar. Ernesto wanted The intended effect ofErnesto's narrative, above, is blatantly obvious. consistent with most be to project to his peers the image of himself that he imagined to this most accomplished He it. the male Discourse as he and his peers constructed mood. and verb aspect effectively through narrative by manipulating habitual actions In Portuguese, the preterit imperfect is usually used to depict to depict nonhabiused is (durative, not restricted in time), whereas the preterit perfect two senfollowing the of example, For tual actions (momentary, restricted in time). reading: habitual a ("whenever") has A tences, only Sentence A. Quando o bebe chorava,eu levantava-me. When (ever) the baby cried, I got up. Quando o bebe chorou,eu levantei-me. When (one time) the baby cried, I got up. preterit imperfect preterit perfect

B.

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS

903

Table 1 The distribution of inflected verbs in text 4. Verb tense, aspect and mood Present indicative Preterit perfect, indicative Preterit imperfect, indicative Preterit, imperfect,

subjective

Number of occurrences 2 9 11

Line numbers of occurrences 27, 34 9, 12, 23, 28, 30, 31, 36, 37, 38 11, 13, 16, 19, 21, 25, 26, 27, 32, 35, 39 18 29 14, 15 9-39

Percentage of total number of inflected verbs 8 35 42

1 1 2 26

4 4 8 lOla

Future, imperfect, subjective Personal infinitive Total

a101% is due to the rounding off of numbers. The total should be 100%.

The use of the preterit imperfect is a strategy especially common in historical writings in which historical events are disguised as timeless or typical. For example, Peixoto (1931:38) wrote of the Indies in the preterit imperfect as follows: As ndias adaptavam-semais facilmente a civiliza?ao, pois se consideravam elevadas pela uniao com os brancos, que nao as desdenhavam~ [quoted in Cunha and Cintra 1986:451, emphasis in original] The Indies adapted more easily to civilization, because they considered themselves superior due to the union with the whites, who did not despise them. [My translation] In consistently emphasizing the habitual or durative aspect of the events he was describing by choosing the preterit imperfect over the preterit perfect, Peixoto disclosed his agenda not as that of recording specific, historically bounded events for posterity, but that of revealing the essence or character of the Indies. According to Cunha and Cintra (1986), the preterit imperfect is also a common verbal strategy in contemporary realist/naturalist fiction in the lusophone world (e.g., Jorge Amado in Brazil, Miguel Torga in Portugal, and Jose Luandino Vieira in Angola) to reduce temporal distance between past and present, thus making events more immediate to the readers.7 In the excerpt above (text 4), Ernesto consistently used verb aspect and, to a lesser extent, mood to depict past events as temporally unrestricted (unfinished, continuous, and permanent). In this brief episode, inflected verbs are distributed as shown in Table 1. If we consider just aspect, then 50 percent of the inflected verbs are in the imperfect. Thirty five percent of verbs are in the perfect. The distribution of inflected verbs for nonrampage narratives of personal experience looks markedly different. Let us look at a representative sample episode from a nonrampage, personal experience narrative Ernesto told immediately after the rampage narrative under study: 5:E: 1 2 neste neste fim de semana eu eu tive this this weekend I I was a quase que fui um pai I was almost a father preterit perfect preterit perfect

904

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

e os meus amigos tambem and my friends too os meus amigos foram as maes my friends were the mothers eufuio pai I was the father nos anddmosali pelos moinhos na nos moinhos we walked around there by the windmills on the windmills ah e encontrdmos la quatro caezinhos ah and we found four puppies there e nos pensdvamos que tavamabandonados and we thought they were abandoned de frio e de fome pra eles nao morrerem so that they wouldn't die of cold and hunger trouxemos para o nosso bairro we brought (them) to our neighborhood deles depois tratdmos then we took care of them a dar leite com um biberon t/vemos-lhe we were feeding them milk with a (baby) bottle houveli um que mamoumeio biberon there was one that sucked half a bottle duma garrafa de coca-cola from a coke bottle (mimicks) bebeu ca com uma esgalha he drank with such fury os outros eratudo a olhar the others were all staring outro a gente tratdmos deles another we took care of them e ate que lhe fizemosuma barraquinha and we even made them a little hut tivemos com com eles tres dias we were with with them three days porque num dia foi tao bonito because one day it was so beautiful a mae deles their mother

no inflected verb

4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit imperfect, preterit imperfect personal infinitive preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect, preterit perfect no inflected verb no inflected verb preterit perfect preterit imperfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect no inflected verb

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS ANDTRANSFORMATIONS

905

23

parece que tinha o faro que os caes tavamali it seems that she could scent that the dogs were there foi a andar ate la she walked right up there e comeqou a ganir assim pra nos and she started yelping at us like this (mimicks) assim a ganir tadinha like yelping the poor thing o que e que ela tava a dizer depois nos nos nao sabiamos then we we didn't know what it was that she was saying e ela come?ou a correr a correr and she started to run to run na direcao onde tava a barraca dos caezinhos in the direction where the puppies' hut was foi pra la she went there assim a esfregar-se na barraca come?ou she started like rubbing herself on the hut e e nos vimosque eraela a mae and and we saw that she was the mother a por/ abrimos we opened the doo/ a porta dos caezinhos abrimos we opened the door to the puppies e ela foi ter com eles and she went to them lambeu-os she licked them

simple present, preterit imperfect, preterit imperfect preterit perfect preterit perfect no inflected verb no inflected verb

24 25

26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37

preterit imperfect, preterit imperfect preterit perfect preterit imperfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect, preterit imperfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect preterit perfect

In this episode, inflected verbs are distributed as shown in Table 2: only 24 percent of the verbs are in the imperfect; a resounding 70 percent are in the perfect. By choosing the imperfect in the rampage narratives, Ernesto accomplished three important objectives. First, by choosing verbal forms that disguised past events as temporally unrestricted ones, Ernesto minimized the element of time, thus effectively conveying the atemporal quality of the state of ecstasy (the sensation of "standing or stepping outside reality as commonly defined," Berger 1967:43) he experienced during the rampage. Such experiences are typical of a state of communitas. As Turner (1974a:238) has argued, "communitas is almost always thought of or portrayed by actors as a timeless condition, an eternal now, as 'a moment in and out of time,' or as a state to which the structural view of time is not applicable." Relatedly, in using the imperfect, Ernesto reduced the temporal distance between past and present, thus making past events more immediate to his audience. Ernesto's choice of the imperfect conflates the

906

ANTHROPOLOGIST AMERICAN

[95, 1993

distribution of The Verb tense, and mood aspect Present indicative Preterit perfect, indicative 26 Number of occurrences 12

2 Table verbs inflected

text in 5. Percentage of total number of inflected verbs 3 70

Line numbers of occurrences 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11,12, 13(2), 16, 19, 20, 21, 24, 18, 29, 31, 32, 33, 25, 35, 36, 37 34,

Preterit imperfect, indicative Preterit, imperfect, subjunctive Future, imperfect, subjunctive Personal infinitive Total 0

8(2), 17,23(2), 28(2), 30, 33 None

24 0 0 3

0 19 37

None

1-37

100

As already noted, this is a absolutedistinction between narrative and experience. in contemporary lusophone ends same the attain to commonliterary strategy used unrestricted by as events temporally in designating realist/naturalistfiction. Lastly, events but as historical as not events usingthe imperfect, Ernesto represented those did. As we he what not he who is, just In other words, the narrative represents typical. historical whereby writing, historical in common have already seen, this is a strategy, are disguised as timeless or typical. events was vague as to what the exact Throughouthis narrative (in Appendix B), Ernesto of the trials, and, consequently, nature the of of events was, but was highly suggestive turn In the narrative, Ernesto trials. such of his own character for having undergone all attributes of a Discourse constructedhimself as powerful, assertive, and courageous, in Ernesto's narrative element hewanted his peers to ascribe to him. The imaginative mood (lines 18 and the of subjunctive revealed explicitly in his use of the imperfect was as those outlined such and Consequences 14 15). 29)and the personal infinitive (lines fact explicitly noted in line 23. inlines 18 through 22 were completely hypothetical, a is once again collapsing Ernesto Inthus enhancing his experiences through narrative, absolute distinctions between narrative and experience. involved were in a self-asThe trials discussed above often happened when the boys too, the rampages are serted temporary state of (nonrational) insanity. In this regard, to which the structural state a timeless condition... 'a moment in and out of time'... "a narratives,boys often viewof time is not applicable" (Turner 1974a:238). In the rampage examples: professed that they and/or their peers were insane, as in the following 6:B(A):

9 10 tava la e eles I was there and they o meu irmao my brother

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS

907

11

elessdo malucos theyare insane

12 13 14

maisos dois companhei/ with the twofrien/ trescompanheirosmeus three friendsof mine la a correra correra correrla nos quintais andavam there theywere runningrunningrunningthroughthe backyards

7:E(B): 1 2 3

4

eu um dia one dayI agorafui ali ter com o Nardo now I went over there to meet Nardo ali com o meu amigo Bemardo there with myfriend Bernardo

e mais malucoque que dois doidos he is moreinsane than two lunatics

These claims appeared at the beginning of rampage narratives only, thus signaling that the proceeding narratives were rampage narratives. The boys' explicit claim that the rampage trialsoften happened when they (the boys) were in a temporary state of insanity is another indication that these experiences were liminal experiences, on the peripheries of the ordinariness of everyday life. Van Gennep (1960[1909] ) and Turner (1974b) both argued that during liminal periods, novices approach mental states close to

insanity.

The temporary experience of marginal mental states is one way in which novices defy their culture's "standard definitions and classifications" (Turner 1974a:232) during liminal periods. During these times, novices are at once no longer classified and not yet classified. Because of this, novices often experience a kind of "invisibility" regarding their culture's "standard definitions and classifications." (Such ambiguous states are necessarily transitory, however, because society does not allow individuals who are permanently, in Turner's famous phrase, "betwixt and between.") In some cultures, physical invisibility is enforced with overt seclusion of the novices. In Ajuda, "invisibility" for nine- and ten-year-old boys manifested itself in at least three ways. First, at the level of the rampage, the boys carried on with their destructive, intrusive behavior because they were not "visible"in the way younger and older children were. My conversations with community members revealed that they more readily tolerated antisocial (rampage-like) behaviors from nine- and ten-year-olds than from either younger or older boys. In Ajuda, it was felt that young children needed to be closely watched and protected, and adults would have perceived rampage-like behaviors on their part as self-endangering and would thus not have tolerated such behaviors. The same behaviors on the part of adolescents, on the other hand, would have been perceived as too invasive and threatening to be tolerated. Nine- and ten-year olds were old enough not to be too closely watched and young enough not to be too threatening. Thus, they benefited from a kind of social invisibility. Second, at the level of the family, nine- and ten-year-old children were more likely to be ignored than ever before in their lives. As already noted, during early childhood, children were under the exclusive vigilance of their caretakers. On public outings,

908

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

children were always supervised by their caretakers. Come late childhood, however, when children gained access to the streets in their immediate environment on their own, they were usually accompanied by adults on outings, but were not necessarily closely supervised. In fact, they were often ignored, and thus they became "invisible" to some extent; consequently, they could sometimes be forgotten or left behind. Diogo, another boy in the study, told one such story. One Sunday, he went on an outing to a public park in the city (as far as I can tell from his description, with at least his parents, his grandmother, his uncle, his aunt, and his cousins). They stayed a while, then they all left for elsewhere, but forgot to take him. So he said: 8:D: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 eu fui la ver ali a esquina duma rua I went there to take a look there at a streetcorner a ver se via alguma coisa to see if I saw anything pois eles foram-se embora then they went away pois eu quando cheguei la then I when I got (back) there ja nao tava la ninguem there wasn't anybody there anymore depois fiquei la assim encostado a then I stayed there like leaning on assim encostado la a uma carrinha like leaning against a station wagon there depois depois dum tempo e que eu then it was after a while that I a minha avo depois viu my grandmother then saw que eu nao tava la com eles that I wasn't there with them e pois e que veio a rua a ver se eu tava la and it was then that she came out to the street to see if I was there pois eu tava la na rua then I was there in the street

Not surprisingly, getting lost was a prevalent fear for boys of this age in Ajuda, and is in the personal experience narratives of the boys in Ajuda (Alves documented 1991:303). Third, at a wider social level, social invisibility was reflected in the lack of services for children of this age. The community provided virtually no social services catering exclusively to children in late childhood, although they did provide more adequate services for younger and older children. Social services in the form of after-school activities for children of this age were all private (thus, unaffordable to working-class people) and, even so, could accommodate only about 6 percent of the children. Thus,

Alves]

ANDTRANSFORMATIONS TRANSGRESSIONS

909

in terms of social services, more than three thousand children were nonexistent, invisible as citizens with rights and needs. Old Men, Walls, and Movement Across cultures, old men often function as bogeymen (van Gennep 1960[ 1909]) for the novices during initiation rites. In many preindustrial societies, elders often disguise themselves and chase the novices, often beating or otherwise maltreating them. The elders may even ritually abduct the novices, which van Gennep considered to be a symbolic celebration of the separation of the novices from their previous environment. In some cultures, these bogeymen may explicitly represent the ancestors who have come back to life specifically for these ceremonies. Even though bogeymen often impersonate death, they are also bearers of a new life for the novices. As van Gennep pointed out, images of death and rebirth into a different state are common in rites of passage. Over the years I have noticed that it is not uncommon for children in early childhood in Portuguese society to fear old men in the community. Mothers often blackmail their children into obeying them by threatening to call whatever old man the children happen to fear. The threat is usually that of abduction. Old men often play along in pretending to be bogeymen. In Ajuda (at least), old men continued to have special functions in late childhood. They were the only adults mentioned in the rampage narratives. The relationship between the boys and the old men during the rampages was alwaysone of

confrontation.

Below is an example of a confrontation with an old man from Ernesto's narrative. At the moment we pick up the action here, Ernesto had just fallen off a wall. So he said: 9:E(B): 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 era eu assim Iwentlike this "bem agoratenho que percorrero caminhopela terra" "well now I have to walkthe restof the wayon the ground" vou conformeeu dou um passo Igo (but) as soon as I take a step um grandavelho aparece-me abig old man appearsin front of me e aindapor cimatraziaum cao andon top of everythinghe had a dog era eu Iwent "iii ola caozinhoja tas a olhar assim muito pra mim "heeehello little dog you'realreadywatchingme waytoo much pernasparaque te quero"pshiu legsdo whatI wantyou for"pst saltopor uma capoeiraacima Ijumpon top of a chicken coop ia partindouma telha Ialmostbrokea (roof) tile

80

910

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

81

salto por ali pelo muro abaixopumba Ijump through there downfrom the wallboom

82 83

por pouco nao cai de cabea Ionly missedfallingon my head by a little quandovi tavamdois caes a olharparamim whenI looked there were twodogs watchingme era eu Iwent "olaaindabem e que tao presos "helloI'm glad you're all chainedup adeuzinho bye bye amanhavolto paravos visitar" tomorrow I'll come backto visityou"

84 85 86 87 88

a correra correra correra correr comego I startto run run run run Several aspects of this episode are deserving of comment. Themain characters are Ernesto himself, the old man, and the old man's dogs. The mainevents are the confrontations with the old man and the dogs. As in text 4, the tellinghighlights the dangers of these incidents. When Ernesto said in line 72 that he had to get off the wall and go the rest of the way on the ground, it was understood that sucha move entailed great danger because it made him more vulnerable to being The fact that he broke a roof tile when he jumped onto the chicken caught. coop (line also highlights the possibility that he might have fallen. In line 80) 82, he entertained the possibility of falling on his head-highly unlikely-again highlighting not just the but all the possible dangers he could think of. (These remarks also real, suggest the intensified nature of the trials.) These courageous feats were further enhanced the fact that Ernesto was not daunted by the danger, but instead confronted it with aby sense of humor, conveyed by the use of sound effects (such as "iii,"line 77; "pshiu,"line 78; and"pumba,"line 81), proverbs (line 78), and his verbally addressing the dogs (lines 77-78 and In we divide up the episode into verses and stanzas (cf. Gee 1990; fact, if85-87). Hymes 1981; Tedlock 1983) so that its organization is revealed, it becomes clear that the purpose of the episode is not to impart any real information, but to make the same point dramatithree times over. The episode is composed of three stanzas. Each cally stanza is thematically organized and all are identically patterned. The first and third stanzas are of four thematic verses: complicating move, dangerous composed consequence, evaluand resolution. The second stanza is slightly abbreviated in that the ation, evaluation is in the dangerous consequence. Specifically, it concerns line 80: implicit a roof breaking when jumping onto a roof implies that the jump was not tie totally successful. The three stanzas are interconnected in that the resolution of one is the complication that the next (see Table 3). The stanzas, then, thematically parallel each other and opens make the same point: that Ernesto courageously overcame the essentially danger at every step. This particular narrative did not detail a full-fledged confrontation with the old man. Others did. The boys knew that they were forbidden to trespass on other people's private and that in doing so they were bound to encounter the property owners/protectors of those spaces (in the rampages, the old men). Such encounters could easily escalate into

Alves]

ANDTRANSFORMATIONS TRANSGRESSIONS

911

Table3 Text 9 dividedinto versesand stanzas.

Complicating move Stanza 1 Stanza 2 Stanza 3 Lines 71-73 Line 79 Line 81 Dangerous consequences Lines 74-75 Line 80 Lines 82-83

Evaluation Lines 76-78 (Implicit) Lines 84-87

Resolution Line 79 Line 81 Line 88

full-fledged confrontations with unwelcome consequences. Any man was assumed to be dangerous in the context of the rampages because, as the boys knew, male honor is intimately connected to the protection of the domestic realm. Male strangers were not, as a rule, threatening in the public realm if they were not infringed on. In general, the public realm was what van Gennep (1960[1909] :18) called neutralzones,spaces "where everyone has full rights to travel." However, men were threatening to those infringing on their private property. In other personal experience narratives, the boys talked about fighting other boys who had infringed on their own private property, a sign that the boys themselves were emerging as protectors of the domestic realm (Alves 1991:193198). Old men became bogeymen in the context of the rampages, and were portrayed as such in the narratives. Boys feared that the old men might chase, beat, or even abduct them; as noted above, ritual abduction of novices by elders is not uncommon in initiation rites across cultures. Abduction to these modem boys, however, usually meant being taken to the police. For example, once a friend of Bernardo's was caught by an old man when he was unable to cross a barbed wire fence during a rampage. The old man said: 10:B(A): 29 30 "aitens que irja ao ao hospital "ohyou haveto go to to the hospitalrightaway porquefizesteali um golpe" becauseyou made a cut rightthere"

To which Bernardo commented: 11:B(A): 31 32 mas o homem era esperto but the man wassmart queriamas era levara pol/cia whathe wantedwasto take (him) to the police

In these narratives, old men were always connected with dogs and weapons. In Ernesto's narrative, it was clear that the old man was threatening in his own right. He was qualified as "a bigold man" ("um grandavelho," line 74 from text 9, above), but he was also accompanied by a dog (sometimes, two dogs). Later in the story, the old man reappeared with a dog and a weapon: 12:E(B):

99 aparece-me o velho corn uma vassoura I see the old man with a broom

912

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

100 101

e com um cao and with a dog

era o cao atrasde mim the dog came afterme The old men could carryall sorts of weapons, the most common of which were a broom or some sort of gardening blade, for example, a weeding hoe (see text 2, line 56, above). An important, striking feature of the rampages is that of constant movement. In the excerpt about the old man (text 9), cited above, Ernesto mentioned running and jumping explicitly only twice each (lines 78 and 88, and 79 and 81, respectively), often highlighted with sound effects (lines 78 and 81, respectively), but the whole story was really about movement and blockades against movement. The old man and his dogs were symbolically significant blockades against freedom of movement through all territories, private and public. Both movement and blockades against movement were elements of symbolic significance in rampage narratives. From a performance point of view, movement is also embedded in the narrativization itself. Ernesto started the narrative at a normal rate of speaking, but periodically increased his rate (especially during lines 11-15 and 41-43). About halfway through the narrative (line 65), he increased his rate and sustained his fast rate until he finished narrating his rampage (line 112). The last few lines (112-125), Ernesto's teasing of Bernardo and his leave taking, were spoken at a normal rate once again. The importance of movement in the rampages is also attested by the greater frequency of verbs requiring physical dislocation between two points in rampage narratives than in nonrampage, personal experience narratives.8If we compare Bernardo's and Ernesto's rampage narrativesthatwe have been discussing (the narrativesin Appendixes A and B, respectively) with two nonrampage, personal experience narratives that the two boys told after the rampage narratives, we get the distribution of verbs shown in Table 4. Clearly, the rampage narratives are significantly more dominated by verbs requiring physical dislocation between two points than nonrampage narratives. Note how movement as a feature of the overall rampage experience interpenetrates both narrative and experience, once again conflating absolute distinctions between the two. Like the old men and their dogs, walls and fences were symbolic blockades against freedom of movement in the rampages recounted in the narratives. A number of the Table 4 of verbsthatdo not requirephysicaldislocationbetweentwo points and those The distribution thatdo requirephysicaldislocationin rampageand nom/aupagenarratives.

Rampage Appendix A: Bernardo (44 lines) Percentage of verbs not requiring physical dislocation between two points Percentage of verbs requiring physical dislocation between two points Difference 53% Appendix B: Ernesto (125 lines) 51% Nonrampage Bernardo (29 lines) 62% Ernesto (66 lines) 81%

47%

49%

38%

19%

6%

2%

24%

62%

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS ANDTRANSFORMATIONS

913

buildings in Ajuda had small, walled-in backyards. Beyond these yards, some people had appropriated small plots of unused land for gardens and for keeping small, domestic livestock such as chickens and rabbits; these plots were either walled or fenced in. Walls were especially symbolic because they separated the various private spaces from public spaces and from one another. Walking on walls was dangerous because it was an ambiguous state. Walking on walls for boys in Ajuda symbolized the fact that they were walking the sensitive dividing line between private spaces, as in the following excerpt: 13:E(B): 41 42 43 44 "oh nao vamos mais rastejar "oh let's not crawl anymore nao vamos mais rastejar let's not crawl anymore vamos ali andar por aqueles muros" let's walk on those walls over there" fomos pelos muros we went on the walls

Ernesto's call to walk on the walls was a challenge because it involved walking on the threshold of another's private space, and thus risking confrontation with those on the other side of the wall. Ernesto was well aware of the precariousness of infringing on someone else's boundaries. In another narrative, Ernesto described in great detail a fight he'd had with a boy because the boy was standing on his (Ernesto's) wall, dirtying it (Alves 1991:193-198). Van Gennep (1960[1909]) pointed out that transitions in social status are usually accompanied by territorial passages, such as entering a house, changing rooms, or crossing streets or squares. In Ajuda, crossing walls was usually an important rite accompanying transitions in social status. The first wall that the boys had to overcome in the path to adulthood was, of course, their own wall to the street. They made this crossing in the transition between early childhood and late childhood, as noted above. By the end of late childhood and the rampages, boys were running well beyond their own wall, but still within limits; some walls were still too difficult for young boys to walk on or cross over. Those who failed to cross difficult barriers or whose crossing was messy tried to justify the outcome to avoid criticism and denigration in the peer group: 14:E(B): 58 59 60 61 62 eu "olha entfaovai tu me "lookyou go then vai por ai que eu vou por aqui go through there and I'll go through here tenho so que saltar pelo quintal" Ionly have to jump through the yard" vou tentar ir por uma por uma parede I'mgoing to try to go on on a wall mas nao consegui but I wasn't able to porquetava bastanteescorregadio it was ratherslippery because

63

914

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

64

e a paredeera assim emdescida e tamem and also and thewall was likeon a decline e ndo tinha nada pra mesegurar and I didn'thave anythingto holdon to tive que cair bumba I had to fall boom

65 66

The younger the boy, the more insurmountable barriers there were. There were many barriers that young boys could not cross, in which case they suffered some repercussion, often an injury, but sometimes getting caught: 15:B(A): 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 eles tinham que passar por baixo do arame farpado they had to cross under the barbed wire senao cortavam assim um bocado da perna or they would cut like a part of the leg eles passaram they crossed e um colega meu and a friend of mine que era o mais pequenino who was the smallest chamado Inacio called Inacio que ele ia a correr that he was running e e fez um golpinho acho que na mao and and cut himself I think on his hand e o homem apanhou-o and the man caught him

The older ones passed (Bemardo's older brother and his friends), but the younger one failed to pass; he was literally weeded out from the older boys. Bernardo himself (a borderline case) refused to participate and was narrating the events secondhand. Those who crossed these difficult barriers gained power and status in the peer group. Those who did not kept trying. Conclusions Communitas is simultaneously dangerous and empowering. As Turner (1974a:243) said, communitas is "a potentially dangerous but nevertheless vitalizing moment, domain, or enclave." Communitas is simultaneously dangerous and empowering because it is a time when novices push the margins of their Discourses. It is dangerous because one's social context (in social structure) is temporarily lost, and instead one experiences a new kind of structure, "one of symbols and ideas, an instructional structure" (p. 240). As Douglas (1966, 1970) argued, "all margins are dangerous. If they are pulled this way or that the shape of fundamental experience is altered. Any structure of ideas is vulnerable at its margins" (1966:121). However, this is exactly why communitas

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS

915

is also empowering. The novice becomes more powerful by venturing beyond the margins of his Discourse as a child and beginning to construct for himself a new Discourse as an adult. He also becomes more knowledgeable, acquiring gnosis,or "deep knowledge" (Turner 1974a:258). As Turner (1974a:258) wrote, it is not merelythat new knowledgeis imparted,but new poweris absorbed,powerobtained through the weaknessof liminalitywhich will become active in postliminallife when the neophytes'socialstatushas been redefinedin the aggregationrites. Douglas (1966) made an explicit connection between states of temporary insanity and power. Like Turner, she argued that temporary insanity is both dangerous and empowering. It is dangerous because such states into which a person enters are indefinable. It is powerful because the individual "who comes back from these inaccessible regions brings with him a power not available to those who have stayed in control of themselves and of society" (p. 95). In short, "to have been to the margins [a condition often expressed by antisocial behavior] is to have been in contact with danger, to have been at a source of power" (p. 97).9 As liminal experiences, rampages were transgressive and transformative in nature. Psychologically, they were ventures "into the disordered regions of the mind" (Douglas 1966:95). Socially, they were ventures "beyond the confines of society" (p. 95). During the rampages, boys acted crazy and did crazy and dangerous things. The flagrant trespassing and destruction of other people's private property was certainly a crazy and dangerous thing to do, because private property was normally considered inviolable in Ajuda. The old man, with his weapons and his dogs, symbolically embodied the danger inherent in violating another person's private space (crossing the forbidden and forbidding walls) if such a violation led to a confrontation. The rampages were also empowering, however, because they were a means for boys to test and push the limits of their social and territorial freedom. The confrontations with the old men were a source of power because they elevated the boys to an equal footing with men, although in a momentary and one-sided way. Of course, later on, the narrative performances empowered the boys in the peer group also. These experiences enabled boys to begin constructing themselves as "men"in their own right. As noted earlier, boys like Ernesto who acted manly by undergoing rampages and skillfully narrativized their experiences before their peers acquired manly stature in the peer group; they became leaders. During the rampages, boys gained new knowledge that prepared them for dealing with the social world afterwards. As Turner said, the novices return to the social world "with more alert faculties perhaps and enhanced knowledge of how things work" (1974a:106). They are thus better prepared to cope with novel situations and take initiative. Turner wrote: For societyrequiresof its maturemembersnot only adherenceto rules and patterns,but at least a certainlevel of skepticismand initiative.Initiationis to rouse initiativeas much as it is to custom.Acceptedschemata to produceconformity andparadigms mustbe brokenif initiates are to cope withnoveltyand danger.Theyhaveto learnhowto generateviableschemataunder environmental challenge. [1974a:256] In Ajuda, boys placed evaluative comments throughout the rampage narratives that showed that they had enhanced their knowledge of behavior in everyday life by participating in the rampages. For example: 16:B(A): 17 18 eles foram theywent passaram por passedthrough

916

AMERICANANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

19

eles tinham que passar por baixo do arame farpado they had to cross under the barbed wire senao cortavam assim um bocado da perna or they would cut like a part of the leg eles passaram they crossed e um colega meu and a friend of mine que era o mais pequenino who was the smallest chamado Inacio called Inacio que ele ia a correr that he was running e e fez um golpinho acho que na mao and and cut himself I think on his hand e o homem apanhou-o and the man caught him ele disse he said "ai tens que irja ao ao hospital "oh you have to go to to the hospital right away porque fizeste ali um golpe" because you made a cut right there" mas o homem era esperto but the man was smart queriamas era levara policia what he wantedwas to take(him) to thepolice

20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32

40 41 42 43

agorajd sei now I know jd ndo vou serparvo I'm not going to beafool anymore ndo vou jd andar aipor essashortas I'm not going to go aroundthrough those fields podem-me apanhar theycouldcatchme

These comments indicate that the boys perceived the rampage trials as practice for adulthood. Gilmore (1990:64-65) noted that the violent initiation rites among the

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS AND TRANSFORMATIONS

917

Trukese are "a kind of basic training for a challenging, demanding male adulthood." The same is true here and may well be true of initiation rites in general. In summary, the rampage was accompanied by a sense of growth, newfound knowledge, and power. A boy's worth as a "man" in the eyes of his peers was dependent on the extent to which he had proved himself worthy. By empowering themselves before their peers through rampage narratives, boys acquired status in the peer group and took an important step toward initiation into the company of men. If they did not prove themselves in the trials of the rampage, then they were mocked if they tried to keep the company of men. Bernardo made this very clear in his description of a picture of a group of fishermen and a boy taking in the daily catch on the shore. In his description, Bernardo mocked the boy for standing around with the men. He said: 17:B: 1 2 3 ta laium miudo no meio dos homens there's a kid there among the men quere-se armar em homem he wants to pretend to be a man coitado the poor thing the boy was too young to have proven himself worthy of the

In Bemardo's judgment, company of men.

MA SmithCollege, is Lecturer, ALVES of EnglishLanguageand Literature, Department Northampton, JULIO 01063. Notes This article is based on a chapter of my Ph.D. dissertation in Applied Linguistics at Boston University (Alves 1991). I would like to thank my readers, Carol Neidle, Beth Goldsmith, and especially my first reader, MaryCatherine O'Connor, for their early comments and support. Part of this article was presented as a paper at the AAA Annual Meeting in December, 1992. 1. Bernardo told the narrative in Appendix A even though he participated in only part of the rampage. Even though Bernardo was not ready to participate in the rampages (he dropped out of the rampages reported in both narratives in the appendixes), he knew at least that public performances of such narrativeswas what it took to acquire power and status in the peer group. This is why he was telling a narrative about events that only his peers experienced first-hand. 2. In his introduction to van Gennep's work, Kimball (1960:VII) noted that "passagemight more appropriately have been translated as 'transition,' but in deference to van Gennep and general usage of the term 'rites of passage,' this form of the translation has been preserved." In this article, I defer to the generic usage of the term, although I, too, prefer the term transition over passagebecause it is more accurate. 3. Van Gennep and Turner preferred the term initiationritesto the more common expression pubertyrites.Van Gennep argued that the term pubertyritesis inaccurate because it confuses physiological puberty and social puberty, two very different processes that do not usually coincide. Physiological puberty may precede social puberty, or vice versa. To complicate matters further, puberty ceremonies often do not occur at the same time as physical manifestations of sexual maturity. For example, van Gennep noted, for Hottentot boys, puberty ceremonies took place at 18 years of age, whereas for Elema boys, the first ceremony took place at 5 years of age, the second at 10, and the third only much later when the boy became a warrior and was free to marry. (The Elema are an ethnic group of the Papuan Gulf.) The evidence seems to indicate that puberty rites are generally not rites of (physiological) puberty per se, but markers of change in gender identity. The term initiation rites refers specifically to social puberty (i.e.,changes in gender identity), not physiological puberty.

918

AMERICANANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

4. A Discourse is defined as "a socially accepted association among ways of using language, of thinking, feeling, believing, valuing, and of acting that can be used to identify oneself as a member of a socially meaningful group or 'social network', or to signal (that one is playing) a socially meaningful 'role'" (Gee 1990:143). In this usage, Discourse with a capital "D" differs from discourse with a lowercase "d."The latter refers to "connected stretches of language that make sense, like conversations, stories, reports, arguments, essays" (p. 142). 5. I never observed girls playing in the street with boys in Ajuda. However, I did ask the boys if girls ever played in the street with them, and they told me that girls did play in the street with them sometimes, but that this was only very occasionally. 6. As already noted, the two narratives that are the main subject of this article are included in full in the appendixes. Excerpts quoted in the body of the article are headed by similar identification codes, for example, 13:E(B). The first number (13) refers to the position of this excerpt in the sequence of primary texts quoted in the article. (In this case, this is the 13th excerpt quoted.) This is followed by the initial of the name of the boy who produced the text (in this case, "E"for Ernesto). The letter in parentheses refers to the appendix where the full narrative can be found (A or B). The line numbers of the entire narrative in the appendix are preserved for easy cross-reference. If an excerpt is not part of one of the narratives in the appendixes, then the parentheses are omitted and the lines are numbered from 1. The texts recorded were transcribed as they were spoken and translated into English. False starts, repetitions, and discursive markers (e.g., the Portuguese equivalent of such expressions as ah and uh in English) all were preserved. I have translated the Portuguese as accurately as possible, and I have tried to convey syntactic awkwardness,where appropriate, in the translations. Line breaks in the transcriptions indicate major pauses. I have also transcribed contractions and phonological reductions common to informal, spoken Portuguese (but not allowed in standard, written Portuguese) as they were spoken. 7. Similar narrativestrategies have been noted for English literature, also. For example, Cohan and Shires (1988) discussed the following passage from D. H. Lawrence's Sons and Lovers (1976:151-152): And gradually the intimacy with the family concentrated for Paul on three persons-the mother, Edgar, and Miriam. To the mother he went for that sympathy and the appeal which seemed to draw him out. Edgar was his very close friend. And to Miriam he more or less condescended, because she seemed so humble. But the girl gradually sought him out. If he brought up his sketch-book, it was she who pondered longest over the last picture. Then she would look up at him. Suddenly, her dark eyes alight like water that shakes with a stream of gold in the dark, she would ask: "Whydo I like this so?" Always something in his breast shrank from these close, intimate, dazzled looks of hers. "Whydo you?" he asked. "I don't know. It seems so true." "It's because-it's because there is scarcely any shadow in it; it's more shimmery, as if I'd painted the shimmering protoplasm in the leaves and everywhere, and not the stiffness of the shape. That seems dead to me. Only this shimmeriness is the real living. The shape is a dead crust. The shimmer is inside really."And she, with her little finger in her mouth, would ponder in these sayings. [Quoted in Cohan and Shires 1988:86-87; emphasis in original] and "always"), In this passage, adverbs (such as "gradually" plural nouns (such as "these sayings and looks"), and the conditional past tense of some verbs (such as "Ifhe brought up," "Then she would look up at him," and "She would ponder these sayings") conflate the past and the present, giving the events a temporal significance that is only possible in narration, not in the actual linear happening of events. 8. For example, verbs such as run, walk, go, jump, return,or bringrequire physical dislocation between two points. Obviously, verbs such as be, want, say, give, arrange,or have require little or no movement, so they clearly do not require physical dislocation between two points. Verbs such as play, hit, open, make,cut, or drink,all of which require some motion, do not require physical dislocation between two points, and so they are classified accordingly as not requiring physical dislocation between two points. 9. Going to the margins involves the kind of momentary discontinuity in social reality that I have been calling temporary insanityhere.

Alves]

TRANSGRESSIONS ANDTRANSFORMATIONS

919

References

Cited

Alves, Julio 1991 The Social Construction of Subjectivitythrough Narrative Discourse: The Case of Urban, Working-Class,Portuguese Boys. Ph.D. dissertation, Program in Applied Linguistics, Boston University. Berger, Peter 1967 The Sacred Canopy. Garden City:Doubleday. Bernard, H. Russell 1967 Kalymnian Sponge Diving. Human Biology 39:103-130. Cohan, Steven, and Linda Shires 1988 Telling Stories: A Theoretical Analysis of Narrative Fiction. London: Routledge. Coon, Carleton 1971 The Hunting Peoples. Boston: Atlantic-Little Brown. Cunha, Celso, and Lindley Cintra 1986 Nova Gramitica do Portugues Contemporaneo. Lisbon: EdicoesJoao Sa da Costa. Douglas, Mary 1966 Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Ark Paperbacks. 1970 Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books. Gee, James P. 1990 Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses. Bristol, UKIThe Falmer Press. Gilmore, David D. 1987 Introduction: The Shame of Dishonor. In Honor and Shame and the Unity of the Mediterranean. David D. Gilmore, ed. Pp. 2-21. Washington, DC:American Anthropological Association. 1990 Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity. New Haven: Yale University Press. Herzfeld, Michael 1985 The Poetics of Manhood: Contest and Identity in a Cretan Mountain Village. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Hymes, Dell 1981 "In Vain I Tried to Tell You" Essays in Native American Ethnopoetics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Kimball, Solon T. 1960 Introduction. In A. van Gennep, The Rites of Passage. Monika Vizedom and Gabrielle Caffee, trans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Lawrence, D. H. 1976 Sons and Lovers. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin. Marcus, Michael A. 1987 "Horsemen are the Fence of the Land": Honor and History among the Ghiyata of Eastern Morocco. In Honor and Shame and the Unity of the Mediterranean. David D. Gilmore, ed. Pp. 49-60. Washington, DC: American Anthropological Association. Marshall, Mac 1979 Weekend Warriors. Palo Alto: Mayfield. Peixoto, Afranio 1931 Noces da hist6ria da literatura Brasileira. Rio de Janeiro: Francisco Alves. Tedlock, Dennis 1983 The Spoken Word and the Work of Interpretation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Turner, Victor 1967 The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1969 The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine. 1974a Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1974b Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow, and Ritual: An Essay in Comparative Symbology. Rice University Studies 60:53-92.

920

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

van Gennep, Arnold 1960[1909] The Rites of Passage. Monika Vizedom and Gabrielle Caffee, trans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Appendix A Bernardo's Rampage Narrative 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 eu tava la num dia I was there one day a brincar comrn o meu irmao nas ferias grandes playing with my brother during summer vacation eramos uns tropas que adivamos a correr pelos quintais we were soldiers who were running through backyards ia ia tum tum (sound effects) e o meu irmao and my brother eu tinha que ir nesse dia ao medico I had to go to the doctor that day e fui-me embora and went away tomei banho I took a bath tava la e eles I was there and they o meu irmao my brother eles sao malucos they are insane mais os dois companhei/ with the two frien/ tres companheiros meus three friends of mine andavam la a correr a correr a correr la nos quintais they were running running running through the backyards there e vinha um homem and a man was coming entao eles eles vinh/ ele so they they com/ he eles foram they went

Alves]

ANDTRANSFORMATIONS TRANSGRESSIONS

921

18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37

passaram por passed through eles tinham que passar por baixo do arame farpado they had to cross under the barbed wire senao cortavam assim um bocado da perna or they would cut like a part of the leg eles passaram they crossed e um colega meu and a friend of mine que era o mais pequenino who was the smallest chamado Inacio called Inacio que ele ia a correr that he was running e e fez um golpinho acho que na mao and and cut himself I think on his hand e o homem apanhou-o and the man caught him ele disse he said "ai tens que irja ao ao hospital "oh you have to go to to the hospital right away porque fizeste ali um golpe" because you made a cut right there" mas o homem era esperto but the man was smart queria mas era levar a policia what he wanted was to take (him) to the police entao o gajo fugiu then the dude ran away acho que tava a rasca de fazer c6c6 nao sei I think he needed to go to the bathroom I don't know e foi he went "oh av6 av6 av6" "oh grandma grandma grandma" e agora tou corn medo que me aconteca isso a mim and now I'm afraid that that might happen to me

922

AMERICANANTHROPOLOGIST

[95, 1993

38 39 40 41 42 43 44