Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2

Uploaded by

juloc34Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2

Uploaded by

juloc34Copyright:

Available Formats

Standards of Practice

Standards for Specialized Nutrition Support: Hospitalized Pediatric Patients

American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Board of Directors and Task Force on Standards for Specialized Nutrition Support for Hospitalized Pediatric Patients: Jackie Wessel, MEd, RD,CNSD, CSP; Jane Balint, MD; Catherine Crill, PharmD, BCPS, BCNSP; and Kimberly Klotz, RN, BSN.

Introduction

The American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) is a professional society of physicians, nurses, dietitians, pharmacists, allied health professionals, and researchers dedicated to assuring that every patient receives optimal nutrition care. A.S.P.E.N.s mission is to serve as the preeminent, interdisciplinary nutrition society dedicated to patient-centered, clinical practice worldwide through advocacy, education, and research in the eld of specialized nutrition support. These Standards for Nutrition Support for Hospitalized Pediatric Patients are an update of the 1996 standards. These standards present a range of performance of competent care based on expert clinical opinion that should be subscribed to by any acute care hospital caring for pediatric patients with or without a formal nutrition support service. A separate reference, Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adults and pediatric patients1 provides evidence-based practice guidelines which are coded to reect the strength of evidence supporting the guideline to assist clinicians in their decision making process in the development of nutrition care plans for patients. Use of the word shall within this document indicates standards to be followed strictly to conform to the standard, use of should indicates that among several possibilities one is particularly suitable, without mentioning or excluding others, or that a certain course of action is preferred but not necessarily required. May is used to indicate a course of action which is permissible within the limits of recommended practice. A list of denitions is included in the

last chapter of this standard to assist the reader to understand terms used in this standard. The standards are presented in the most generic terms possible. The details of specic tests, therapies, and protocols are left to the discretion of individual hospital nutrition support services, teams, or appropriate interdisciplinary hospital nutrition committees. Ideally, each healthcare institution should have a formal interdisciplinary team responsible for specialized nutrition support (SNS). It is recognized, however, that this is often not feasible in todays medical economic climate. Each institution shall strive to provide the best nutrition support structure that is possible given the resources of the institution. The standards aim to assure sound and efcient nutrition care for those hospitalized pediatric patients in need of SNS. These standards do not constitute medical or other professional advice, and should not be taken as such. To the extent that the information published herein may be used to assist in the care of patients, this is the result of the sole professional judgment of the attending healthcare professional whose judgment is the primary component of quality medical care. The information presented in these standards is not a substitute for the exercise of such judgment by the healthcare professional. Intent statements are included to provide additional information and guidance in interpreting the standards.

CHAPTER I: Organization

Standard 1. Nutrition Support Service Delivery of nutrition care services requires coordination of work and collaboration among departments and professional groups. A nutrition support service or nutrition care team shall function to assess and manage patients determined to be nutritionally-at-risk.2 1.1 When an organized nutrition support service or team exists, it shall be directed by a practitioner who by appropriate education, specialized training, and/or experience is knowledgeable in the delivery of SNS.2

103

Correspondence: A.S.P.E.N., 8630 Fenton St, Ste 412, Silver Spring, MD 20910. Electronic mail may be sent to aspen@nutr.org.

0884-5336/05/2001-0103$03.00/0 Nutrition in Clinical Practice 20:103116, February 2005 Copyright 2005 American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition

104

A.S.P.E.N.

Vol. 20, No. 1

Figure 1. The nutrition care process.

1.2 An organized nutrition support service should include a physician, nurse, dietitian, and pharmacist, each following standards of practice for their discipline.36 1.3 If a nutrition support service or team is not established, SNS should be managed by an interdisciplinary approach and should include the patients physician, nurse, dietitian, and pharmacist.2 1.4 Health care professionals involved with nutrition support of pediatric patients shall be competent to assess the nutrition status and manage the SNS of that population. Standard 2. Policies and Procedures Written policies and procedures for the provision of SNS shall be established.2 2.1 The policies and procedures shall be created with the input and review of all members of the nutrition support service or team.2 2.2 The policies and procedures shall be reviewed and revised as appropriate to ensure optimal patient care.2 Standard 3. Performance Improvement The nutrition support service or interdisciplinary team shall review and report on team performance, patient outcome data, and cost of services. 3.1 The review of performance should assess the appropriateness and effectiveness of the administration of SNS to individual patients. 3.2 Performance improvement mechanisms to initiate policy, procedure, or protocol changes that enhance the safety and efcacy of provision of SNS shall be recommended by the

nutrition support service or interdisciplinary team.

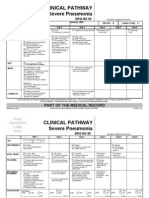

CHAPTER II: Nutrition Care Process

Standard 4. Nutrition Screening2 The process of nutrition care and the administration of SNS require a series of steps with feedback loops. These steps include nutrition screening, nutrition assessment, formulation of a nutrition care plan (NCP), implementation of the plan, patient monitoring, reassessment of the care plan, reevaluation of the care setting, and then either reformulation of the care plan or termination of therapy.1,2 The nutrition care process is outlined in Figure 1. Patients who are nutritionally-at-risk should be identied by nutrition screening. Criteria specic to pediatrics shall be established for identication of pediatric patients who are nutritionallyat-risk.7,8 4.1 The policy and procedure for nutrition screening shall be formalized and documented.2 4.2 All patients admitted to the hospital shall be screened for nutritional risk within 24 hours.2 4.3 The result of the nutrition screen shall be documented and appropriate intervention initiated.2 4.4 A procedure for nutrition re-screening should be implemented.2 Intent of Standard The primary purpose of the pediatric nutrition screen is to determine when a pediatric patient is nutritionally-at-risk and when a detailed pediatric nutrition assessment is indicated. Pediatric screening criteria should include, but not be limited to:

February 2005

STANDARDS: HOSPITALIZED PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

105

pediatric patients on altered diets, formulas or diet schedules; diagnoses associated with specic nutrition requirements/problems; recent change in body weight or dietary intake; and growth failure or altered weight/length or weight/height relationships. Pediatric patients with specic nutrition requirements or problems may include: premature infants, ill newborns, those receiving extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, critically ill patients, transplant and bone marrow transplant patients, obese patients, those receiving home SNS and patients with necrotizing enterocolitis, short bowel syndrome, inammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal pseudo-obstruction, intractable diarrhea, liver disease, chronic renal failure, diabetes mellitus, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, cystic brosis, central nervous system disorders, cancer, eating disorders, and inborn errors of metabolism. Examples of pediatric screening mechanisms hospitals could develop or use may include but not be limited to: a nutrition checklist performed by the nurse; identication of specic disease codes; and a review of admitting parameters (for example, National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) growth chart percentiles, serum albumin level or iron indices). The pediatric screening mechanisms should include but not be limited to: chronological age; gestational age (for neonates and infants); gender; weight; length or height; and head circumference (for children less than 3 years of age). Intent of Standard The screening process should be fast and efcient so that resources may subsequently be allocated to those patients with current problems or who are nutritionally-at-risk. Screening has been implemented by most hospitals in order to comply with standards of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations9; no evidence-based literature exists to support these standards, nor has it been shown that assessment within 24 hours of admission actually has an impact on the outcome of pediatric hospitalized patients. Because of the 24-hour, 7-day-a-week time requirement for the initial nutrition screen, many organizations use staff nurses to complete the nutrition screening during the admission process. These screens are generally shorter in length than more in-depth screens that include laboratory values, but have the advantage that they can be done efciently and in a timely fashion.2 Standard 5. Nutrition Assessment All pediatric patients identied as nutritionallyat-risk by the pediatric screening mechanism shall undergo a nutrition assessment.1,10 13 This nutrition assessment shall be documented and be available to all patient care providers. The intent of the nutrition assessment is to document baseline subjective and objective nutrition parameters, determine nutritional risk factors, identify specic nutri-

tional decits, establish nutritional needs for individual patients, and identify medical, psychosocial, and socioeconomic factors that may inuence the prescription and administration of SNS.2 5.1 The nutrition assessment shall be performed by or under the supervision of a registered dietitian with pediatric experience or in conjunction with other health care professionals with pediatric nutrition expertise, within a timely manner as specied by institutional policy. 5.2 The nutrition assessment shall include subjective, and objective assessment of the patients current nutrition status and nutritional requirements. 5.2.1 The subjective assessment of nutrition status should include, but not be limited to: a nutritionally focused history, eg, feeding tolerance, dietary intake patterns, feeding skills development, and psychosocial/religious/cultural factors that affect intake. Elements that should be documented as part of the subjective assessment of nutrition status include caregiver perception of previous growth history (qualitative), ideal body weight, recent changes in body weight, adequacy of current nutrient intake, recent changes in dietary intake; development of oral motor skills; gastrointestinal problems (including stomatitis, gastrointestinal intolerance, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation and anorexia), current status and recent changes in functional capacities, eg, ambulation, activities of daily living, school activities, developmental delays, and physical activity level. 5.2.2 Clinical data gathered for the nutrition assessment should include but not be limited to: admitting diagnosis; concurrent medical and surgical problems that may affect nutritional requirements and nutrition support options (including allergies and medications). 5.2.3 The objective assessment of nutrition status should include data obtained from clinical, anthropometric and laboratory evaluations. Elements that should be documented as part of the objective assessment of nutrition status of pediatric patients should include but not be limited to: growth indices both previous and current (including percentiles as appropriate); birth anthropometrics as appropriate; head circumference (for patients 3 years of age); height (length); current weight; 50% for weight/height (length); and Tanner stage1, as appropriate. While malnutrition has long been recognized as a con-

106

A.S.P.E.N.

Vol. 20, No. 1

cern14,15 the overweight patient is equally concerning. Children and adolescents are identied at risk for overweight with a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles. Children and adolescents with a BMI greater than the 95th percentile are considered overweight. Children and adolescents experiencing rapid increases in BMI of 3 to 4 units per year are also considered at risk of developing obesity.14 All of the above parameters should be obtained via age, appropriate measurement techniques and documented on the appropriate standardized growth chart. Specialized growth curves exist for premature infants as well as infants and children with diagnoses such as Trisomy 21,16 Turner,17 Williams,18 and Prader-Willi syndromes;19 quadriplegic cerebral palsy.20 Often the NCHS curves are used in combination with the specialized curves for growth evaluation.21 Some of the specialized curves are based on a small sample size and some are based on older data prior to more aggressive nutrition practice.22 A discussion of the benets and drawbacks of some of the growth curves is provided elsewhere.23,24 Elements of the physical exam relevant to nutrition status should be evaluated (eg, loss/lack of subcutaneous fat, muscle wasting, edema, ascites, mucocutaneous lesions, and hair changes). Any recent laboratory studies should be reviewed and additional studies might include: renal prole, glucose, CBC, electrolytes, calcium, magnesium, phosphorous, serum proteins and others based on clinical condition. Intent of Standard Postnatal growth parameters should be corrected for gestational age at birth for very low birth weight (VLBW) infants for at least 2 years.22,24 25 Many references are available for assessment of growth over time for VLBW infants.26 32 An evaluation of these references has been provided elsewhere.22 If the Infant Health and Development Program (IHDP) is chosen to evaluate VLBW infants, it should be noted that it was developed in 1985 before the use of more aggressive medical and nutritional standards of care, which potentially could improve growth status. The most recent VLBW growth charts only extend to 120 postnatal days or 2000 grams.30 Although the Center for Disease Control (CDC) growth charts do not include infants below 1500 grams in the data set, it is the only chart available for infants over 36 months or for stature after 24 months.33 The CDC charts can be adjusted

to view a VLBW infant against nonVLBW infants. The growth percentiles and z scores are on the CDC web site.34 5.3 The subjective and objective assessments of nutrition status shall be summarized and documented. A system may be used to classify nutritional risk. 5.3.1 Patients nutritional requirements shall be summarized based on the subjective, clinical, and objective nutrition assessments. The summary should include protein, fat, and calorie target requirement. The summary should also include uid, electrolyte and micronutrient requirements that will not be met by standard oral, enteral, or parenteral feedings. 5.4 Nutrition assessment shall include an evaluation of psychosocial and socioeconomic factors that may inuence prescription and administration of nutrition support. Intent of Standard Factors that may be included in the psychosocial portion of the nutrition assessment include: family dynamics; language barriers, neurobehavioral status (eg, developmental status); family ethnic, cultural or religious dietary prescriptions; psychiatric disorders (patient or caregiver); prognosis; family nancial situation (eg, participation in the Women, Infants and Children program); and family preferences and directives with regard to intensity and invasiveness of care. 5.4.1 The psychosocial assessment of nutrition status shall be documented. The summary should include an overall assessment of the appropriateness of SNS for the individual patient. 5.5 Nutrition assessment shall include an assessment and documentation of factors relevant to route of SNS administration. Relevant factors may include the following: ability to suck/swallow (infants) or other age appropriate feeding skills ( 1 year old); presence of gag reex; functional status of the gastrointestinal tract; mental status; developmental status; enteral and vascular access; and schedule of tests and invasive procedures.

CHAPTER III: Development of a Nutrition Care Plan

Standard 6. Objectives The nutrition care plan (NCP) is the template for nutrition therapy and is created by analysis of information from many aspects of care, including consultations, therapies, and assessments. The NCP should include nutrient requirements and intake goals, route of SNS administration, and measurable short-and long-term objectives of care and intervention.2

February 2005

STANDARDS: HOSPITALIZED PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

107

Standard 7. Interdisciplinary Approach The NCP should be developed using an interdisciplinary team approach2 involving the nutrition support service, the patients physician and other health care personnel with pediatric experience. The NCP should be developed using a family centered approach. The American Dietetic Association has adopted a Nutrition Care Process as a systematic problemsolving process for dietetics professionals to critically think and make decisions to address nutrition related problems and provide safe and effective nutrition care. This involves the establishment of nutrition diagnoses and is described elsewhere.35 Standard 8. Goals and Expectations The NCP should include patient/caregiver education about goals and expectations of SNS and should incorporate patient/caregiver wishes.2 Goals should be established to dene the desired outcome of therapy. This assures that therapy provides optimal, appropriate and resource-efcient family centered care. It also establishes a patient-specic set of goals that should be used to continually assess the efcacy of therapy and adequacy of growth. Routes of administration appropriate for use shall be dened, and identication of requirements for nutrient intake shall be included.2 Standard 9. Selection of Route The route selected to provide SNS shall be appropriate to the patients medical condition. 9.1 Enteral nutrition (EN) should be used in preference to parenteral nutrition (PN) to the greatest extent possible.2 9.2 PN should be used when the gastrointestinal tract is not functional or cannot be accessed, or the patients nutrient needs are greater than those which can be met through the gastrointestinal tract. 9.3 The route of SNS administration should be reassessed for adequacy and appropriateness. Standard 10. Selection of Formulation The EN or PN formulation shall be appropriate for the patients disease process and route of access. 10.1 The EN or PN formulation shall be adjusted as appropriate in patients with growth failure and/or organ dysfunction. 10.2 When similarly effective EN or PN formulations are available and tolerated, the least costly should be selected. 10.3 When signicant amounts of nutrients are provided through means other than the feeding formulation (eg, parenteral infusions, drugs, uids, continuous arteriovenous hemodialysis), the formulation should be adjusted accordingly.

CHAPTER IV. Implementation

Standard 11. Ordering Process Implementation of the NCP shall follow nutrition assessment and development of a formal NCP. 11.1 Implementation of a NCP shall have a dened ordering process. 11.1.1 Prescriptions/orders for food or SNS products shall be documented in the patients medical record before administration.9 11.1.2 Verbal prescriptions/orders for food or SNS shall be accepted only by personnel designated by institutional policy and should be signed by the prescribing/ ordering practitioner within a dened time period.9 Standard 12. Nutrition Support Access Access for SNS shall be achieved and maintained in a manner that minimizes risk to the patient.1,11,13 12.1 Access devices shall be placed by or under the supervision of a physician, nurse, or specially trained healthcare professional who is procient in placement of access devices in children and who is competent and knowledgeable in recognizing and managing complications associated with the placement and maintenance of access devices. 12.2 Access devices shall be placed safely, effectively and humanely in children. Methods for appropriate sedation or anesthesia, use of sterile technique and selection of appropriate catheter size and material shall be dened. 12.3 Standard techniques and protocols shall be established and followed for access device insertion and routine care 12.4 Proper placement of vascular and enteral access devices shall be appropriately conrmed and documented in the medical record before use. 12.4.1 Central venous access shall be obtained prior to the administration of central parenteral nutrition. The catheter tip should be positioned in the distal portion of the superior vena cava or at the superior vena cava adjacent to the right atrium.36 12.5 Complications related to an access device and outcome of actions to manage the complications shall be clearly documented in the medical record. Intent of Standard Technical complications (e.g., pneumothorax, catheter occlusion, breakage, accidental removal, venous thrombosis) and infectious complications (bacteremia, fungemia, entry site infection) shall be recorded in the childs medical record and reviewed periodically. Strategies to reduce the risk of compli-

108

A.S.P.E.N.

Vol. 20, No. 1

cations should be designed, implemented and documented. Standard 13. Parenteral Nutrition Formulation Preparation PN formulations shall be prepared accurately and safely as prescribed. 13.1 PN formulations shall be prepared using current and established policies and procedures regarding sterile compounding,37 compatibility, stability, sterility and labeling.2 These procedures shall be supervised by a licensed pharmacist. 13.2 Automated equipment used for the preparation of PN formulations shall be cared for properly. 13.2.1 Policies and procedures for the use of automated compounding devices for PN formulations shall be developed to address responsibilities for operation, calibration and maintenance, staff training, and checking and monitoring compounder performance at all times.37 13.2.2 Personnel shall be trained in proper operation, calibration and maintenance of the equipment. 13.2.3 Personnel shall be trained in the use of computer software to assist in daily use and trouble shooting of automated compounding equipment. 13.2.4 Documents generated by the automated compounding device shall be compared with the PN formulation that is ordered.2 13.2.5 The operator shall monitor the equipment continuously during the preparation process to assure the proper operation of the equipment. 13.3 PN formulations shall be sterile. 13.3.1 PN formulations shall be prepared in a laminar or vertical airow hood by an individual trained in aseptic technique under the direction of or by a licensed pharmacist. 13.3.2 The preparation area should be a class 100 environment38 with limited access to decrease the potential for microbial contamination. 13.3.3 Aseptic technique shall be taught, used and validated on a periodic and routine basis. 13.3.4 Sterility testing shall be performed on a regular surveillance basis. 13.4 PN formulations shall be visually inspected to identify signs of gross contamination, particle formation, or phase separation during the preparation process, before hanging, and during administration of the formulation to identify potential incompatibilities of the formulation.

13.5 If repackaging of fat emulsions is conducted, methods should be taken to ensure sterility, including preparation in a laminar or vertical airow hood and utilization of appropriate infusion hang-times.39 13.6 All PN formulations shall be prepared in compatible containers.2 Methods should be taken to limit the amount of aluminum contamination in PN formulations.40,41 Standard 14. EN Formulation Preparation EN formulations shall be prepared accurately and safely as prescribed. 14.1 EN formulations shall be prepared and stored according to manufacturers recommendations and using current and established policies and procedures, published data and/or written institutional policies regarding manufacturing, compatibility, stability, sterility and labeling.42 Example of Implementation The pediatric department requests that certain infant formulas be prepared in concentrated form (e.g., 24 and 27 kcal/oz) in addition to the standard 20 kcal/oz. An institutional policy is developed to establish standards for preparation of the formulas in these concentrations. 14.2 EN formulations shall be prepared by trained personnel under professional supervision with appropriate credentials and experience using established preparation guidelines.42,43 14.3 Commercially sterile, ready to feed or liquid concentrate formulas prepared with sterile water using aseptic technique should be used in all neonatal intensive care settings, in neonatal and infant patients, and those that may be immunocompromised. Powdered formula should be used only when no alternative comparable formula is available.44 14.4 A separate room should be available for the preparation of infant formula, expressed breast milk, and enteral feedings. In facilities where that is not possible, a dedicated clean space with facilities for aseptic technique should be available.45 14.5 Preparation equipment should be sanitized regularly according to institutional guidelines. 14.6 A quality control plan following Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP) guidelines should be developed to ensure and assess sanitary techniques in the preparation, handling, storage, and administration of EN formulations.46,47 14.7 Guidelines should exist for the expression, storage and handling of expressed breast milk.48,49 14.8 Guidelines should exist for the use of donor human milk as a feeding alternative for

February 2005

STANDARDS: HOSPITALIZED PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

109

infants whose mothers are unable to provide human milk. Donor human milk shall be pasteurized.50,51 14.9 Guidelines should exist that delineate the institutions response to a batch error or a manufacturers formula recall.47 Standard 15. Additives Components added to a PN formulation shall be appropriate and compatible with all ingredients and shall be added safely and accurately. 15.1 Additions to PN formulations shall be listed on the label. 15.2 Healthcare professionals responsible for the preparation and delivery of PN formulations shall employ methods for detection and prevention of formulation incompatibilities.2,50 15.2.1 All additions to a PN formulation shall be made in a laminar or vertical airow hood under the direct supervision of or by a licensed pharmacist. 15.2.2 Individuals who inject additives into PN formulations shall be trained in proper sterile technique. 15.2.3 The addition of medications or other nutrients to PN formulations after they have left the pharmacy shall be discouraged. 15.2.4 Healthcare professionals responsible for the addition of drugs or nutrients to PN formulations shall have resources available to verify compatibility and stability of any additives. 15.3 Protocols should be established to dene acceptable minimum and maximum amounts of specic nutrients and additives in PN formulations. 15.4 The sequence of addition of calcium and phosphorous to PN formulations should be optimized to prevent calcium/phosphorous precipitation.2,50 15.4.1 Calcium gluconate is the preferred calcium salt and should be used in PN formulations. 15.4.2 Phosphorous salts shall be added to the PN formulation, before any other formulation additive. 15.4.3 Calcium should be added near the end of the compounding sequence to take advantage of the maximum volume of the PN formulation. 15.4.4 Some amino acid formulations contain phosphate ions. This additional amount of phosphate should be accounted for in the calculation of calcium/phosphorous solubility. 15.5 Deviation from established policies and procedures should require approval by a healthcare professional who is knowledgeable about phys-

ical-chemical compatibilities, drug-drug and drug-nutrient interactions. Intent of Standard Professionals who are knowledgeable in physical/chemical compatibilities and drugdrug and drug-nutrient interactions should supervise the direct addition or co-infusion of nutrients or drugs with PN formulations to assure compatibility and stability of the formulation and the added product. Example of Implementation A neonatal patient receiving PN develops radiographic evidence of rickets. The pharmacist, using published data, is able to switch to a different amino acid source and adjust pH by changing some of the additives. This shifts the solubility curve of calcium and phosphorus and allows a signicant increase in the amounts that can be given safely. 15.6 All pediatric patients receiving PN should receive daily parenteral multivitamins in quantities established by the Subcommittee on Pediatric Parenteral Nutrition Requirements from the Committee on Clinical Practice Issues of The American Society for Clinical Nutrition.51 Dosing may need to be adjusted in severe renal and hepatic dysfunction, excessive losses, or in patients receiving long-term PN. In the event of parenteral multivitamin product shortage, multivitamin use may need to be adjusted per patient population. Institutions should follow the recommendations for multivitamin administration during shortages set forth by A.S.P.E.N. 15.7 All pediatric patients receiving PN should receive daily parenteral trace elements in quantities established by the Subcommittee on Pediatric Parenteral Nutrition Requirements from the Committee on Clinical Practice Issues of The American Society for Clinical Nutrition.51 Dosing shall be adjusted for severe renal and hepatic dysfunction, excessive losses, or in patients receiving long-term PN1. In the event of a parenteral multiple trace element product shortage, trace elements should be dosed individually. Institutions should follow the recommendations for trace element administration during shortages set forth by A.S.P.E.N. 15.8 Components added to EN formulations shall be appropriate and compatible with all ingredients and shall be added safely and accurately. 15.8.1 Healthcare professionals responsible for the preparation and delivery of EN formulations shall employ methods for detection and prevention of formulation incompatibilities. 15.8.2 Protocols should be established to dene acceptable minimum and maximum amounts of specic nutrients in EN formulations.

110

A.S.P.E.N.

Vol. 20, No. 1

15.8.3 Procedures and policies shall be established regarding subsequent additions to EN formulations, including dilution of formula and addition of medications. Any additions to the formulation shall be ordered by the prescribing practitioner or designee and documented by the formulating personnel and should be consistent with published guidelines.2,52 15.8.3.1 Macronutrient additives should be added in the formula room. 15.8.3.2 All additives should be included as part of the EN label. Intent of Standard Additions to EN formulations that are nutritional products, such as protein, carbohydrate, and fat fortiers, should be added to the enteral formulation at the time of compounding in the formula room. These additives should be included on the EN label. Other additives to enteral formulations, such as electrolytes, are often individualized over a daily period. Based on institution specic protocols, these products may be added to the EN formulation by the bedside nurse. Any additional additives to an EN formulation after leaving the formula room should be noted on the label. 15.8.3.4 Colorants (food coloring and methylene blue) should not be added to enteral feeding products.53 Blue dyes have been used in feedings to detect aspiration visually. The safety, sensitivity, and specicity of blue tinted enteral feedings has not been documented.5458 Case reports have associated the use of FD&C Blue No. 1 to serious adverse events and death, although a direct casual relationship has not been proven.5963 Methylene blue toxicity has also been described.64 Microbial contamination of feedings has also been associated with the use of dye dispensed from multiple dose containers.65 Standard 16. Packaging and Labeling PN and EN formulations shall be packaged, labeled and stored to assure stability and compatibility. In addition, the label should identify the formula composition and administration information.

16.1 PN formulations shall be packaged in containers that can assure maintenance of sterility and allow visual inspection during preparation, storage and administration.50 16.1.2 PN formulations shall be labeled with the patients name, additives, rate of administration, expiration date and time, and composition. The content and format of a PN label should follow the standard label format for neonate or pediatric patients as recommended by the National Advisory Group on Standards and Practice Guidelines for Parenteral Nutrition.50 16.1.3 PN formulations should be stored at 4C.2 16.2 EN formulations shall be packaged in containers to assure the least contamination possible and accuracy of volume. 16.2.1 EN formulations shall be clearly and conspicuously labeled to include the following as identied in Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities:43 patients name, medical record/ID number, patients location, base formula plus additives, caloric density/volume, volume in container, expiration date and time (24 hours after formula preparation), route of administration, frequency or rate of administration, for be enteral use only and refrigerate until used. Shake well also may be included as a reminder to nursing staff to agitate the formula before decanting it into an individual unit or volufeed. 16.3 Expressed human milk shall be stored in food grade plastic or glass containers.49 16.3.1 Human milk shall be labeled with the infants name, medical record number, date and time of expression, and any medications taken by the mother, fresh or frozen, contents in container (expressed breastmilk), date and time milk thawed, and expiration (based on whether the milk was fresh or frozen) Standard 17. Administration of SNS Formulations PN and EN formulations shall be administered accurately in accordance with the prescribed therapeutic plan and consistent with the patients tolerance.2 17.1 SNS formulations shall be administered by or under the supervision of trained personnel.2 17.2 The type and volume of PN and EN formulations, the rate of administration, and tolerance to the feeding shall be documented in the childs medical record.

February 2005

STANDARDS: HOSPITALIZED PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

111

17.3

17.4

17.5

17.6 17.7

17.8 17.9

17.2.1 A protocol should exist to insure accurate settings on pump rates prior to and during an infusion period. The label on the formulation shall be checked against the order before administration of the formulation to assure the prescribed formulation is compounded correctly and that the formulation is given to the appropriate patient and by the correct route. PN formulations shall be checked visually for particulate material or precipitates prior to and during administration. In the case of total nutrient admixtures (TNAs), the solution should be checked for signs of deterioration.66 PN formulations shall be administered with an in-line lter.50 0.22-micron lters should be used for 2-in-1 formulations. 1.2-micron lters shall be used for TNAs. The use of a 2-in-1 formulation with the separate infusion of fat emulsion should be used in neonatal and infant patients.50 Methods should be established to limit patient exposure to the plasticizer di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) while providing EN and PN. Products without the plasticizer DEHP are preferred67 especially in patients receiving fat emulsions and fat containing products. The rate of prescribed administration shall be checked each time a new volume of formulation is ordered and during its administration. Institution specic protocols and procedures shall exist regarding techniques used to administer PN and EN formulations. 17.9.1 Protocols shall be written to prevent and manage vascular or enteral access device occlusion. 17.9.2 A protocol shall be written to prevent and manage patient infections caused by contamination of the formulation and/or the equipment used in its administration. 17.9.3 A protocol shall be written regarding the time within which PN and EN formulations shall be used before its contents become unstable or pose an infectious risk to the patient. 17.9.3.1 PN formulation infusion must be completed within 24 hours of initiating the infusion or the remaining formulation shall be discarded.68 17.9.3.2 Fat emulsion infused separately from PN formulations must be completed within 12 hours of initiating the infusion or the remaining fat emulsion shall be discarded.2 If volume considerations require more time, fat emulsion infusion

should be completed within 24 hours of initiating the infusion or the remaining fat emulsion shall be discarded.68 17.9.3.3 Formulations shall be labeled with administration and discard date and time.2 17.9.4 Cycling on PN formulations should be considered in select patients, such as those on long term PN or those with cholestasis.69,70 Intent of Standard The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends limiting fat emulsion infusion rates in low birth weight infants to less than 0.12 g/kg/hr. In this patient population, it may be necessary to infuse fat emulsions over periods greater than 12 hours.68 Other pediatric patients may also require longer infusion times, depending on uid restrictions and clinical status. 17.9.4 A protocol shall be written regarding the maximal rate for fat emulsions. Manufacturers recommendations should be considered in formulating this protocol.2 17.9.5 A protocol shall be written to minimize the risk of microbial contamination of EN formulations.2 17.9.5.1 Commercially sterile, readyto-feed formulas that have been carefully poured from the packaged container into a tube feeding system should be used within the time that is recommended by the manufacturer. 17.9.5.2 Hang time for continuous feeding of human milk should be 4 hours or less. Hang times for formula for newborns in a newborn intensive care unit or for other immune suppressed patients should be 4 hours or less. Hang times for other pediatric patients on commercially sterile ready to feed formula should be 8 hours and 4 hours when using powdered formulas or formulas made with nonsterile additives.52 Feeding sets should be changed every 4 hours for human milk or non sterile formulas, and changed every 8 hours for use with sterile products in the non immune compromised pediatric patient. 17.9.5.3 Facility prepared formula not immediately refrigerated

112

A.S.P.E.N.

Vol. 20, No. 1

should be used within 4 hours.52 17.9.5.4 Formulations shall be discarded at the time of expiration listed on the label.2 17.9.6 Protocols and procedures should exist to minimize the risk of regurgita- tion and aspiration of EN formulations.2 17.9.7 A protocol shall exist to prevent the inadvertent administration of an EN formulation through a vascular access device.2,71 Syringe pumps and intravenous pumps are sometimes used for EN administration for their accuracy at low feeding volumes. Caution should be used to make sure that enteral products and pumps are not accidentally used for intravenous administration. Feeding sets that have a unique color and connector should be used only for enteral feedings. 17.9.8 Guidelines should exist that delineate the institutions response to the misadministration of human milk.49 Standard 18. Sentinel Event Management A sentinel event related to the administration of SNS shall be reported according to hospital protocol to assure that the event is properly documented and that a corrective action plan can be instituted. This process reduces the risk of the development of a serious adverse outcome in the future.9

CHAPTER V: Monitoring and Re-evaluation of the NCP

Standard 19. Parameters and Frequency A plan for monitoring the effect of nutrition interventions should be stated in the NCP.1 Monitoring parameters are chosen relative to the goals of the NCP and should include therapeutic and adverse effects and clinical changes that may inuence nutrition therapy. The NCP shall be revised to optimize SNS and achieve predetermined outcomes for the patient.2 19.1 Protocols should be developed to obtain baseline weight, height or length, and head circumference to be plotted on an age appropriate growth curve, and for periodic review of the patients growth, development, clinical and laboratory status. 19.2 The frequency of monitoring should depend on gestational age, postnatal age, disease, severity of illness, degree of malnutrition, and level of metabolic stress.1 Daily or more frequent monitoring may be required for neonates, infants, critically ill patients, and those who have debilitating diseases or infection, are at risk for refeed-

ing complications, are transitioning between PN or EN and oral diet, or have experienced complications associated with SNS.2 19.3 Monitoring parameters may include the following:1,2 Physical assessment, including clinical signs of uid and nutrient excess or deciency. Vital signs Actual uid and nutrient intake (oral, enteral, and parenteral) Measurement of output (urine, gastrointestinal, wound losses, chest tube drainage). Weight (height and head circumference in infants with prolonged hospital stay) Laboratory data (complete blood count, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, electrolytes (Na, K, Cl, CO2), calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, liver function tests, triglycerides, serum proteins, or INR, urine glucose, urine sodium, urine specic gravity). The burden of the test, including consideration of the blood volume required to do the test, should be balanced by the benet or usefulness of the results, particularly in small infants and those who have been on a stable parenteral or enteral regimen. Review of medications Changes in gastrointestinal function indicating tolerance of nutrition therapy (such as ostomy output, stool frequency and consistency, presence of blood in the stool, presence of abdominal distention, increasing abdominal girth, nausea, vomiting. Intent of Standard In neonates in particular, and in patients with selected disease states, an assessment of uid intake and output should accompany an evaluation of weight gain to determine whether the source of the weight increase is uid or lean body mass. 19.4 Abnormalities in monitoring parameters shall be identied. Recommended changes in SNS formulation, volume, or route shall be made in writing and resulting outcomes shall be documented.2 Standard 20. Procedures Monitoring procedures for SNS administration shall include the following: 20.1 Visual inspection of the patients enteral or parenteral access devices and insertion site.2 20.2 Periodic check of the SNS label, expiration date, and infusion rate setting.50 20.3 Inspection of the SNS formulation before administration for signs of gross contamination, particle formation, and phase separation of lipid emulsions.50 20.4 Review of patient medication prole for the following:2

February 2005

STANDARDS: HOSPITALIZED PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

113

Potential effects on both nutrition and metabolic status Incompatibilities with SNS formulation1 Standard 21. Re-evaluation of NCP The patient shall be monitored for progress toward short- and long-term objectives as dened in the NCP.2 21.1 Appropriate parameters should be measured serially during SNS and documented.1 Parameters may include weight change, growth in height or length, head circumference change, appropriateness of growth and development, adequacy of intake and output, ability to transition to enteral or oral diet, changes in laboratory data, achievement of developmental milestones, functional status performance, and quality of life. 21.2 The monitoring parameters should be compared with the goals of the NCP. The frequency of comparison should be based on the patients gestational and/or postnatal age, disease or condition, medical stability, tolerance of nutrition therapy, and progress toward achievement of goals. If goals are not being met or new problems/risks have arisen, the NCP should be modied or rewritten as appropriate. Adjustments to the SNS formulation or volume necessitated by an infants growth shall be identied and recommendations documented in writing. Guidelines for frequency of reassessment for given patient populations and nutrition therapies should be developed. Revision of the nutrition care plan goals shall involve the patient, caregiver, and health care professionals, as appropriate. The cost effectiveness of the updated nutrition care plan shall be evaluated in terms of the potential risks and benet for the patient.

Standard 23. Continuity of Care There shall be continuity of care and active communication with all members of the care team (the patient, parents and/or caregivers, and members of the medical team) to develop a plan for transition of SNS.2 If the patient requires extended SNS, home care should be considered. Every effort should be made to secure home health care nurses and home infusion agencies that are competent in pediatric care. Standards for home PN and EN support need to be followed.72 23.1 Hospitals should develop protocols for discharge criteria for home EN and PN support. 23.2 Patients and/or caregivers should be adequately trained in administration and monitoring of home EN and PN prior to hospital discharge to assure safe administration.11 Standard 24. Termination of Therapy Protocols to address the termination of SNS shall be developed. These protocols shall acknowledge the use of clinical judgment in accordance with accepted standards of medical ethics, local practice standards and local, state, and federal law.2 24.1 Minors, functionally competent patients,73 parents/guardians, and/or the legal surrogate of minor or incompetent patients shall be involved in decisions regarding withholding or withdrawing of treatment.74 Minor patients and previously functionally competent minor patients wishes shall be considered in making decisions to withhold/withdraw SNS.73,74 24.2 SNS should be modied or discontinued when there are disproportionate burdens or when benet can no longer be demonstrated.1,2 Example of Implementation In certain patient cases of terminal illness when EN is not feasible the use of PN may be used to improve and/or maintain quality of life.

CHAPTER VII: Denitions CHAPTER VI: Transition of Therapy

Standard 22. Adequacy of Intake The child should demonstrate appropriate nutrient intake and growth on enterally administered nutrients or oral nutrients prior to the termination of PN and removal of a vascular access device. 22.1 During the transition to EN, PN should be continued while EN is increased. 22.2 Adequate oral intake and growth should be demonstrated and documented prior to termination of SNS. 22.3 When appropriate, SNS should be gradually decreased as oral intake increases so that overall adequate nutrient intake and growth are sustained. Admixture. The result of combining two or more uids. Automated Compounding Device. A device used in the preparation of PN. It automates the transfer of dextrose, amino acids, fat emulsion, sterile water as well as small volume injectables, such as electrolytes and minerals to the nal PN container. The device is driven by computer software. Beyond-use date. The date established by healthcare professionals from the published literature or manufacturer-specic recommendations for intravenous sterile preparations beyond which the pharmacy-prepared product should not be used. Compatibility. The combination of 2 or more chemical products such that the physical integrity of the products is not altered. Incompatibility refers to concentration-dependent precipitation or acid-base

114

A.S.P.E.N.

Vol. 20, No. 1

reactions that result in physical alteration of the products when combined together. DEHP. di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, a plasticizer used in various intravenous administration sets or plastic infusion bags. Drug-drug interaction. An event that occurs when a drugs activity, availability, or effect is altered by another drug. Drug-nutrient interaction. An event that occurs when nutrient availability is altered by a medication, or when a drug effect is altered or an adverse reaction caused by the intake of nutrients. Enteral Access Devices. Tubes placed directly into the gastrointestinal tract for the delivery of nutrients or drugs. Enteral Nutrition(EN). Nutrition provided through the gastrointestinal tract. OralEnteral nutrition taken by mouth. TubeEnteral nutrition provided through a tube, catheter, or stoma that delivers nutrients distal to the oral cavity. Expiration date. The date established from scientic studies to meet FDA regulatory requirements for commercially manufactured drug products beyond which the product should not be used. Formulation. A ready-to-administer mixture of nutrients. Hang time. The period of time beginning with the ow of a uid through an administration set and catheter or feeding tube and ending with the completion of the infusion. Indicators. Prospectively determined measures used as normative standards within a Performance improvement process. Intravenous fat emulsion (IVFE). An intravenous oil-in-water emulsion of oil(s), egg Phosphatides and glycerin. The term should be used in preference to lipids. Malnutrition. Any disorder of nutrition status including disorders resulting from a deciency of nutrient intake, impaired nutrient metabolism, or overnutrition. Nutrition assessment. A comprehensive approach to dening nutrition status that uses medical, nutrition, and medication histories; physical examination; anthropometric measurements; and laboratory data. A formal nutrition assessment should provide all of the information necessary to develop an appropriate NCP. Because of the inextricable relationship between malnutrition and severity of illness and the fact that tools of nutrition assessment reect both nutrition status and severity of underlying disease, an assessed state of malnutrition or presence of specic indicators of malnutrition in fact refers to the consequences of a combination of an underlying illness and associated nutritional changes and decits. Nutritionally-at-risk. Neonates should be considered at nutritional risk if they have: Very low birth weight (1500 gm) or low birth weight (2500 gm) even in the absence of

gastrointestinal, pulmonary, or cardiac disorders. Birth weight less than 2 standard deviations below the mean (approximately the 3rd percentile for gestational age on fetal weight curves. Acute weight loss of 10% or more. Nutritionally-at-risk. Children should be considered at nutritional risk if they have: A weight/length or weight for height less than the 10th percentile or greater than the 90th percentile. Increased metabolic requirements. Impaired ability to ingest or tolerate oral feedings. Documented inadequate provision or tolerance of nutrients. Inadequate weight gain or a signicant decrease in an individuals usual growth percentile. Nutrition Care. Interventions and counseling of individuals on appropriate nutritional intake through the integration of information from the nutrition assessment. Nutrition Care Plan (NCP). A formal statement of the nutrition goals and interventions prescribed for an individual using the data obtained from a nutrition assessment. The plan formulated by an interdisciplinary process, should include statements of nutrition goals and monitoring parameters, the most appropriate route of administration of SNS (oral, enteral, and/or parenteral) method of nutrition access, anticipated duration of therapy, and training and counseling goals and methods. Nutrition Screening. A process to identify an individual who is malnourished or who is at risk for malnutrition to determine if a detailed nutrition assessment is indicated. Nutrition Support Service (or Team). A multidisciplinary group of healthcare professionals including a physician, nurse, dietitian, and pharmacist with expertise in nutrition who manage the provision of SNS. Nutrition therapy. A component of medical treatment, that includes oral, enteral, and parenteral nutrition Outcome. The measured result of the performance of a system or process. Parenteral Nutrition (PN). The administration of nutrients intravenously. Central. Parenteral nutrition delivered into a large-diameter vein, usually the superior vena cava. Peripheral. Parenteral nutrition delivered into a peripheral vein, usually of the hand or forearm. Sentinel Event. An unexpected death or serious injury that is not related to the natural course of the patients illness. Specialized Nutrition Support (SNS). Provision of nutrients orally, enterally, or parenterally with therapeutic intent. This includes, but is not limited

February 2005

STANDARDS: HOSPITALIZED PEDIATRIC PATIENTS

115

to, provision of total enteral or parenteral nutrition support and provision of therapeutic nutrients to maintain or restore optimal nutrition status and health. Stability. The extent to which a product retains, within specied limits,a dn throughout its period of storage and use (i.e., its shelf-life), the same properties and characteristics that it possessed at the time of its manufacture. Standard. Benchmark representing a range of performance of competent care that should be provided to assure safe and efcacious care. Total Nutrient Admixtures (TNAs). A parenteral nutrition formulation containing IVFE as well as the other components of PN (carbohydrate, amino acids, vitamins, minerals, trace elements, water and other additives) in a single container. Vascular Access Device(VAD). A device inserted into a vein which permits administration of intermittent or continuous infusion of parenteral solutions or medications.

References

1. Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations Board of Directors. 2003 Comprehensive Accreditation Manual for Hospitals: The Ofcial Handbook. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2003. 2. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors and Task Force on Standards for Specialized Nutrition Support for Hospitalized Adult Patients. Standards for specialized nutrition support: adult hospitalized patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2002;17:384 391. 3. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors. Standards of practice for nutrition support nurses. Nutr Clin Pract. 2001;16:56 62. 4. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors. Standards of practice nutrition support dietitians. Nutr Clin Pract. 2000;15:5359. 5. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors. Standards of practice nutrition support pharmacists. Nutr Clin Pract. 1999;14:275281. 6. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors and Task Force on Standards for Nutrition Support Physicians. Standards of practice nutrition support physicians. Nutr Clin Pract. 2003;18:270 275. 7. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors and the Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26(Suppl):SA1138SA, errata:1002;26:144. 8. Nevin-Folino N. Pediatric Diet Manual. Chicago, IL: Amer Diet Assoc, 2003. 9. Cox JH. Obesity. In: Cox JH, ed. Nutrition Manual for At-Risk Infants and Toddlers. Chicago, IL: Precept Press, 1997. 10. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors. Clinical Pathways and Algorithms for Delivery of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition Support in Adults. Silver Spring, MD: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; 1998. 11. Klotz KA, Wessel JJ, Hennies GA. Goals of Pediatric Nutrition Support and Nutrition Assessment. In: Merritt R, ed. The A.S.P.E.N. Nutrition Support Practice Manual. Silver Spring, MD: American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition, Silver Spring, MD; 1998;23-123-13. 12. American Dietetic Associations denitions for screening and nutritional assessment. J Amer Diet Assoc. 1994;94:838 839. 13. Schwenk WF, Olson D. Pediatrics. In: Gottschlich M, ed. The Science and Practice of Nutrition support. A Case-Based Core Curriculum. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co.; 2001; 347354. 14. Nevin-Folino N. Nutrition assessment for adolescents. In: NevinFolino N, ed. Pediatric Manual of Clinical Dietetics, 2nd ed. Chicago, IL: Amer Diet Assoc, 2003;167. 15. Waterlow JC. Classication and denition of protein-calorie malnutrition. Br Med J. 1972;3:566 569.

16. Cronk C, Crocker AC, Pueschel SM, et al. Growth charts for children with Down Syndrome. Pediatr. 1988;81:102110. 17. Lyon AJ, Preece MA, Grant DB. Growth curve for girls with Turner Syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1985;60:932935. Commercially available from Genentech, Inc., 1987. 18. Morris CA, Demsey MS, Leonard CL, et al. Height and weight of males and females with Williams Syndrome. Williams Syndrome Assoc Newsletter, Summer 1991;29 30. 19. Butler MG, Meany FJ. Standards for selected anthropometric measurements in Prader-Willi syndrome. Pediatr. 1991;88:853 858. 20. Krick J, Murphy-Miller P, Zeger S, Wright E. Pattern of growth in children with cerebral palsy. J Am Diet Assoc. 1996;96:680 685. 21. Bonnema S. Neurological Compromise. In: Cox JH ed. Nutrition Manual for At-Risk Infants and Toddlers. Chicago, IL: Precept Press; 1997;113133. 22. Sherry B, Mei Z, Grummer-Stawn L, Dietz WH. Evaluation and recommendations for growth references for very low birth weight (1500 grams) infants in the United States. Pediatr. 2003;111: 750 757. 23. Cox JH. Growth Assessment. In: Cox JH, ed. Nutrition Manual for At-Risk Infants and Toddlers. Chicago, IL:Precept Press; 1997;4358. 24. Elliman AM, Bryan EM, Harvey DR. Gestational age correction for height in preterm children to seven years of age. Acta Paediatr. 1992;81:836 839. 25. Wang Z, Sauve RS. Assessment of postnatal growth in VLBW infants: selection of growth references and age adjustment for prematurity. Can J Public Health. 1998;89:109 114. 26. Babson SG, Benda GI. Growth graphs for the clinical assessment of infants of varying gestational age. J Pediatr. 1976;89:814 820. 27. Brandt I. Growth Dynamics of low birth weight infants with emphasis on the perinatal period. In: Falkner F, Tanner JM, eds. Human Growth: 2. Postnatal Growth. New York, NY: Plenum Press, 1978;557 617. 28. Casey PH, Kraemer HC, Bernbaum J, et al. Growth patterns of low birth weight preterm infants: longitudinal analysis of a large, varied sample. J Pediatr. 1990;117:298 307. 29. Casey PH, Kraemer HC, Bernbaum J, Yogman MW, Sells JC. Growth status and growth rates of a varied sample of low birth weight, preterm infants: longitudinal cohort from birth to three years of age. J Pediatr. 1991;119:599 605. 30. Ehrenkranz RA, Younes N, Lemons JA, et al. Longitudinal growth of hospitalized very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics. 1999;104:280 289. 31. Guo SS, Wholihan K, Roche AF, Chumlea WC, Casey PH. Weight for length reference data for preterm, low birth weight infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150:964 970. 32. Gairdner D, Pearson J. A growth chart for premature and other infants. Arch Dis Chil. 1971;46:783787. 33. Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Guo SS, et al. 2000 CDC growth charts for the United States: methods and development. Vital Health Stat. 2002;11.246:1190. 34. CDC website www.cdc.gov/growthcharts 35. Lacey K, Pritchett E. Nutrition care process and model: ADA adopts road map to quality and outcomes management. JADA. 2004;103:10611072. 36. Collier PE, Goodman GB. Cardiac tamponade caused by central venous catheter perforation of the heart: a preventable complication. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:459 463. 37. ASHP Council on Professional Affairs. ASHP guidelines on the safe use of automated compounding devices for the preparation of parenteral nutrition admixtures. Am J Health Sys Pharm. 57(Special Report), 2000. 38. (797) Pharmaceutical CompoundingSterile Preparations. United States Pharmacopeial Convention, Pharmacopeial Forum. 2003;29:940 965. 39. Sacks GS, Driscoll DF. Does Lipid Hang Time Make a Difference? Time is of the Essence. Nutr Clin Pract. 2002;17:284 290. 40. A.S.P.E.N. Aluminium Task Force and A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors. A.S.P.E.N. statement on aluminum in parenteral nutrition solutions. Nutr Clin Pract. 2004;19:416 417.

116

A.S.P.E.N.

Vol. 20, No. 1

41. U.S. Food and Drug Administration Proposed Rule. Aluminum in large and small volume parenterals used in total parenteral nutrition. Fed Register. 1998;63:176 185. 42. Robbins ST, Beker LT. Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities. Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association, 2004. 43. Teske S. Personnel. In: Robbins ST and Beker LT, eds. Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities. Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association; 2003;2327. 44. Teske S, Robbins ST. Formula Preparation and Handling. In: Robbins ST, Beker LT, eds. Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities. Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association; 2004;34 43. 45. Whaley T. Physical Facilities. In: Robbins ST, Beker LT, eds. Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities. Chicago, IL: Am Diet Assoc; 2004;10 17. 46. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration, 1999 Food Code Annex 5, HACCP Guidelines. Available at http://www.cfsan.fed.gov. Accessed on August 14, 1997. 47. Teske S. Quality Assurance. In: Robbins ST, Beker LT, eds. Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities. Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association; 2004;107118. 48. The Association of Womens Health, Obstetric, and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN). Evidence Based Clinical Practice Guideline: Breastfeeding Support: Prenatal Care Through the First Year. AWOHNN, 2000. 49. Sapsford A, Lessen R. Expressed Human Milk. In: Robbins ST, Beker LT, eds. Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities. Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association, 2004, pgs 68 81. 50. Safe Practices Taskforce and A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors. Safe practices for parenteral nutrition. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;S39 S70. 51. Greene HL, Hambidge KM, Schanler R, Tsang RC. Guidelines for the use of vitamins, trace elements, calcium, magnesium, and phosphorous in infants and children receiving total parenteral Nutrition: Report of the Subcommittee on Pediatric Parenteral Nutrient Requirements from the Committee on Clinical Practice Issues of The American Society for Clinical Nutrition. AJCN. 1998;48:1324 1342. 52. Hutsler D. Delivery and bedside management of infant feedings. In: Robbins ST, Beker LT, eds. Infant Feedings: Guidelines for Preparation of Formula and Breastmilk in Health Care Facilities. Chicago, IL: American Dietetic Association; 2004;88 95. 53. McClave SA, DeMeo MT, DeLegge MH, et al. North American summit on aspiration in the critically ill patient: Consensus statement. JPEN J Parenteral Enteral Nutr. 2002;26(Suppl): S80 S85. 54. Brady S, Hildner C, Hutchins B. Simultaneous videouoroscopic swallow study and modied Evans blue dye procedure: An evaluation of blue dye visualization in cases of known aspiration. Dysphagia. 1999;14:146 148. 55. Metheny NA, Dahms TE, Stewart BJ, et al. Efcacy of dyestained enteral formula in detecting pulmonary aspiration. Chest. 2002;122:276 281.

56. Metheny NA, Myra AA, Wunderlich RJ. A survey of bedside methods used to detect pulmonary aspiration of enteral formula in intubated tube fed patients. Am J Crit Care Med. 1999;8:160 167. 57. Potts RG, Zaroukian MH, Guerrero PA, Baker CD. Comparison of blue dye visualization and glucose oxidase test strip methods for detecting pulmonary aspiration of enteral feedings in intubated adults. Chest. 1993;103:117121. 58. Thompson-Henry S, Braddock B. The modied Evans blue dye procedure fails to detect aspiration in the tracheotomized patient. Comments. Dysphagia. 1995;10:172175. 59. FDA Public Health Advisory: Reports of blue dye discoloration and death in patients receiving enteral feedings tinted with the dye, FD&C No. 1. Sept 29, 2003. 60. Maloney JP, Halbower AC, Fouty BF, et al. Systemic absorption of food dye in patients with sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1047 1048. 61. Maloney JP, Ryan TA, Brasel KJ, et al. Food dye use in enteral feedings: A review and a call for a moratorium. Nutr Clin Pract. 2002;17:169 181. 62. Maloney JP, Ryan TA. Detection of aspiration in enterally fed patients: a requiem for bedside monitoring of aspiration. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26(Suppl):S34 S42. 63. Reyes FG, Valim MF, Vercesi AE. Effect of organic synthetic food colours on mitochondrial respiration. Food Addit Contam. 1996; 13:511. 64. Albert M, Lessin MS, Gilchrist BF. Methylene Blue: dangerous dye for neonates. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1244 1245. 65. File TM Jr, Tan JS, Thomson RB Jr, Stephens C, Thompson P. An outbreak of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ventilator-associated respiratory infection due to contaminated food coloring dye: further evidence of gastric colonization preceding nosocomial pneumonia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1995;16:417 418. 66. McKinnon BT, Avis KE. Membrane ltration of pharmaceutical solutions. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50:19211936. 67. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Notication: PVC Devices Containing the plasticizer DEHP. Food and Drug Administration Letter, July 12, 2002. 68. OGrady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 51(RR10):129, 2002. 69. Collier S, Crouch J, Hendricks K, Caballero B. Use of cyclic parenteral nutrition in infants less than 6 months of age. Nutr Clin Pract. 1994;9:65 68. 70. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition: Nutritional needs of LBW infants. Pediatrics. 1985;75:976 986. 71. Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation. Enteral feeding set connectors and adapters. Nutr Clin Pract. 1997;12(1). 72. A.S.P.E.N. Board of Directors. Standards for home nutrition support. Nutr Clin Pract. 1999;14:151162. 73. Freyer D. Care of the dying adolescent: special considerations. Pediatrics. 2004;113:381388. 74. Committee on Bioethics, Guidelines on Forgoing Life Sustaining Medical Treatment. Pediatrics. 1994;93:532536.

You might also like

- Adult Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) : Suicide Risk AssessmentDocument4 pagesAdult Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) : Suicide Risk Assessmentjuloc34No ratings yet

- PSO - Largo Plazo - Switch Kim PappDocument13 pagesPSO - Largo Plazo - Switch Kim Pappjuloc34No ratings yet

- CXG 055eDocument3 pagesCXG 055eKishor MaloreNo ratings yet

- Start Now Before A PotDocument2 pagesStart Now Before A Potjuloc34No ratings yet

- CXG 055eDocument3 pagesCXG 055eKishor MaloreNo ratings yet

- Lahiri 2 - Unlocked PDFDocument5 pagesLahiri 2 - Unlocked PDFjuloc34No ratings yet

- Lahiri 2 - Unlocked PDFDocument5 pagesLahiri 2 - Unlocked PDFjuloc34No ratings yet

- Hospital Admission For Heart Failure: An Opportunity To Optimize Heart Failure Therapy?Document27 pagesHospital Admission For Heart Failure: An Opportunity To Optimize Heart Failure Therapy?juloc34No ratings yet

- Neuropsychiatric Manifestations of Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiencies: Data From An Inpatient Psychiatric DepartmentDocument2 pagesNeuropsychiatric Manifestations of Vitamin B12 and Folate Deficiencies: Data From An Inpatient Psychiatric Departmentjuloc34No ratings yet

- RTC-SW 2014 10 P Anaemia in Pregnancy GuidelineDocument5 pagesRTC-SW 2014 10 P Anaemia in Pregnancy GuidelineShiina LeeNo ratings yet

- Why, When, and How: Seize The Moment To Optimize Treatment For Each Patient With Heart FailureDocument7 pagesWhy, When, and How: Seize The Moment To Optimize Treatment For Each Patient With Heart Failurejuloc34No ratings yet

- Joint Statement ESPGHANESPACI1999Document8 pagesJoint Statement ESPGHANESPACI1999juloc34No ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Levofloxacin and Amoxycillin/clavulanic Acid in Adults With Mild-To-Moderate Community-AcquiredDocument9 pagesComparative Study of Levofloxacin and Amoxycillin/clavulanic Acid in Adults With Mild-To-Moderate Community-Acquiredjuloc34No ratings yet

- Baker Et Al-2003-Arthritis & Rheumatism PDFDocument13 pagesBaker Et Al-2003-Arthritis & Rheumatism PDFjuloc34No ratings yet

- Fucosylated Human Milk OligosaccharidesDocument8 pagesFucosylated Human Milk Oligosaccharidesjuloc34No ratings yet

- ACR 2011 Clinicians GuideDocument7 pagesACR 2011 Clinicians Guidejuloc34No ratings yet

- 87ri7 113Document11 pages87ri7 113juloc34No ratings yet

- IDF - Atlas 2015 - UK PDFDocument144 pagesIDF - Atlas 2015 - UK PDFjuloc34No ratings yet

- 731 1457 1 PBDocument4 pages731 1457 1 PBjuloc34No ratings yet

- A134 oct06DunnS335toS344 06Document10 pagesA134 oct06DunnS335toS344 06juloc34No ratings yet

- 8w812 Outdoor Photographer August 2015 HQ PDFDocument92 pages8w812 Outdoor Photographer August 2015 HQ PDFjuloc34No ratings yet

- Actualización Guías Tratamiento Ar Acr 2012Document15 pagesActualización Guías Tratamiento Ar Acr 2012Felipe VasquezNo ratings yet

- Effect of Iron-Deficiency Anemia On Cognitive Skills and Neuromaturation in Infancy and ChildhoodDocument7 pagesEffect of Iron-Deficiency Anemia On Cognitive Skills and Neuromaturation in Infancy and Childhoodjuloc34No ratings yet

- Efficacy and Safety of Vismodegib in Patients With Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) : 12-Month Update of The ERIVANCE BCC StudyDocument1 pageEfficacy and Safety of Vismodegib in Patients With Advanced Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) : 12-Month Update of The ERIVANCE BCC Studyjuloc34No ratings yet

- Residual Neuromuscular Block: Lessons Unlearned. Part II: Methods To Reduce The Risk of Residual WeaknessDocument12 pagesResidual Neuromuscular Block: Lessons Unlearned. Part II: Methods To Reduce The Risk of Residual Weaknessjuloc34No ratings yet

- Iron Metabolism and Requirements in Early Childhood: Do We Know Enough?: A Commentary by The ESPGHAN Committee On NutritionDocument9 pagesIron Metabolism and Requirements in Early Childhood: Do We Know Enough?: A Commentary by The ESPGHAN Committee On Nutritionjuloc34No ratings yet

- Residual Neuromuscular Block: Lessons Unlearned. Part II: Methods To Reduce The Risk of Residual WeaknessDocument12 pagesResidual Neuromuscular Block: Lessons Unlearned. Part II: Methods To Reduce The Risk of Residual Weaknessjuloc34No ratings yet

- Hyman Roma IIIDocument8 pagesHyman Roma IIIjuloc34No ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Chan VS ChanDocument2 pagesChan VS ChanEduard RiparipNo ratings yet

- A Copy of The Formal Complaint Filed by The Texas Medical Board Against Dr. Mary BowdenDocument12 pagesA Copy of The Formal Complaint Filed by The Texas Medical Board Against Dr. Mary BowdenHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- Clinical Pathways Severe PneumoniaDocument2 pagesClinical Pathways Severe PneumoniaaandakuNo ratings yet

- Medical Records, Insurance, and ContractsDocument32 pagesMedical Records, Insurance, and ContractsBernard Kwaku OkaiNo ratings yet

- Career Test Result: Personality Types and Holland CodesDocument4 pagesCareer Test Result: Personality Types and Holland Codesapi-307132793No ratings yet

- QPS Sample GuidelinesDocument23 pagesQPS Sample GuidelinesSafiqulatif AbdillahNo ratings yet

- RCL Employment Medical Examination Form A (New-Returning) Revised 2015-03Document2 pagesRCL Employment Medical Examination Form A (New-Returning) Revised 2015-03Ahmad ShodiqNo ratings yet

- NSG Process-Chitra MamDocument44 pagesNSG Process-Chitra MamJalajarani AridassNo ratings yet

- Apex Manual RPOCDocument70 pagesApex Manual RPOCtanisha100% (1)

- Ethics Professional Conduct: American Dental AssociationDocument24 pagesEthics Professional Conduct: American Dental AssociationMavisNo ratings yet

- Short Term Training Curriculum Handbook PHLEBOTOMISTDocument33 pagesShort Term Training Curriculum Handbook PHLEBOTOMISTrokdeNo ratings yet

- Activity Design June 2017 Program Title: Iclinicsys Training RationaleDocument2 pagesActivity Design June 2017 Program Title: Iclinicsys Training Rationalepedrong dodongNo ratings yet

- Pad 411 - Health AdministrationDocument177 pagesPad 411 - Health AdministrationMuttaka Turaki Gujungu100% (1)

- March 13, 2015 Letter To Dr. Kristina Borror at OHRPDocument4 pagesMarch 13, 2015 Letter To Dr. Kristina Borror at OHRPLeighTurnerNo ratings yet

- Little Harwood Health Centre Practice LeafletDocument5 pagesLittle Harwood Health Centre Practice Leafletkovi mNo ratings yet

- The Wayland News July 2011Document20 pagesThe Wayland News July 2011Julian HornNo ratings yet

- J Applied Clin Med Phys - 2022 - Fisher - AAPM Medical Physics Practice Guideline 12 A Fluoroscopy Dose Management-1Document19 pagesJ Applied Clin Med Phys - 2022 - Fisher - AAPM Medical Physics Practice Guideline 12 A Fluoroscopy Dose Management-1Roshi_11No ratings yet

- Anecdotal RecordsDocument21 pagesAnecdotal Recordsvanshika thukral80% (10)

- Know Your Hospital: Submitted by Joyita ChatterjeeDocument13 pagesKnow Your Hospital: Submitted by Joyita ChatterjeeJoyita ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Article Electroinc Medical Records Stimulation For Nursing Students 3 5Document2 pagesLiterature Review Article Electroinc Medical Records Stimulation For Nursing Students 3 5Andrea TylerNo ratings yet

- Pinamalayan Doctors' Hospital: Policies and ProcedureDocument9 pagesPinamalayan Doctors' Hospital: Policies and Procedurefredie rick luceNo ratings yet

- Proctoring Policy 5 12Document6 pagesProctoring Policy 5 12Dwi cahyaniNo ratings yet

- Secondary Use of Electronic Health RecordDocument19 pagesSecondary Use of Electronic Health RecordRaksha hiwaNo ratings yet

- MLC Area 02 - Medical Fitness - ILO - 2011-00-00 - Guidelines On The Medical Examinations of SeafarersDocument69 pagesMLC Area 02 - Medical Fitness - ILO - 2011-00-00 - Guidelines On The Medical Examinations of SeafarersMilan ChaddhaNo ratings yet

- Relevant Ethico-Legal GuidelinesDocument17 pagesRelevant Ethico-Legal GuidelinesPauline M.No ratings yet

- Healthcare Administration Resume ExamplesDocument7 pagesHealthcare Administration Resume Examplesafayememn100% (2)