Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Professional Pilgrim

Uploaded by

Ashutosh MohanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Professional Pilgrim

Uploaded by

Ashutosh MohanCopyright:

Available Formats

The professional pilgrim

Ashutosh Mohan

Nallappa practiced a peculiar vocation: he was a professional pilgrim. Early every

morning, he pedalled an old-fashioned rickshaw that was improvised into a

perambulating shrine, from one of those abominably putrid side streets that lovingly

hug Central Station, into the heart of residential Madras to solicit money and

offerings; he would eventually make a 1,500 kilometre journey to Shirdi and deposit

them on the slightly exaggerated and symbolic feet of Sai Baba, a mendicant saint

who lived and died there over a hundred years ago.

Nallappas first encounter with Sai Baba was as a five-year old toddler living in a

concrete pipe measuring three feet in diameter along one of the highways of Bihar

that had the privilege of being in a state of perennial construction and mending. One

night, his father had brought home a calendar that was forthcoming of details

exclusively regarding months between August and December of the last year. Above

some numbers that meant nothing to Nallappa, who couldnt read, or to the others,

who didnt bother to read, was a picture of Sai Baba; he had deigned to sit with a

folded left leg flattened cleanly on the floor and an oblique right leg, folded again.

Nallappa would stand in front of the portrait and move a foot to the left and then to

the rightthe Babas eyes seemed to follow his movement.

The boy is a bastard and a fool. Nallappa would be able to cleanly recollect the

words of a father whose name he would not be able to recollect with any consistency.

I hope Baba gives him sense. He has to start earning his keep in a couple of years.

Those prophetic words came true. An earthquake that struck Bihar in 1988

exacerbated social fault lines; seismic emigration of the wretchedly poor to other

states followed. Nallappa ended up in Tamil Nadus capital city: Madras, a chaotic

and hopeful metropolis that was scurrying to find its own identity.

***

I come from Bihar, master. I am looking for a job here. Nallappas lucid declaration

was lost on the Central Station tea stall owner who couldnt understand a word of

Hindi. He hated the language simply because his beloved and ever-young Tamil

sounded like honey poured into the ears; he had also forbidden his two daughters from

learning Hindi. His wife brought the family much needed extra income by conducting

Hindi tuitions on their porch in evenings. Fractures in communication inflicted by

linguistic and political standoff were plastered by earnest mime. Nallappa was hired

as an errand boy in exchange for a salary of protecting him from the police who were

not as cruel to outsiders as corporation men were to stray dogs.

Nallappa trivially achieved an existence free from the tyranny of money by losing his

family in Bihar, making his way to wherever fortune took him, and welcoming

whatever came his way. Being an errand boy kept him away from hunger, sorrow and

the law. In due course, Nallappa helped marry the tea mans daughters. He especially

enjoyed playing chauffeur for the post-marriage ceremonial drive around the

neighbourhood in an old mongrel of a car decorated with gaudy flowers; finally, he

deposited the newlyweds into their first nighta trenchant expression with

unbelievable assumptions causing no self-consciousness in anyone.

He had graduated from an errand boy to an errand man and felt the need to move on

on life.

***

I wish I were still an errand boy in my tea shop. Nallappa told his wife, a sigh that

frequently admixed with his speech rendered the last words strongly wistful.

She continued serving him food, grumbling about how the two girls were pestering

her to send them to school.

We cannot afford to send them to school, preempted Nallappa.

Only because you cannot find a better job.

Yes. I agree. said Nallappa in a tone of rehearsed resignation and reconciliation.

But what will they do with education after all? Baba has given us this life and we

should not ask for more. I cannot wait to get them married myself and then disappear

from everything altogether.

What do you meandisappear?

Nallappa capitalised on this distraction to segue into the quotidian. Oh nothing. Do

you think we can afford a fridge? The girls like to eat ice cream everyday.

I dont think so. We cant buy a fridge with the kind of money you make.

We might be able to, if you give Hindi tuitions like madam used to do. Maybe the

girls can give tuitions too when they grow up. That will be very useful to their

husbands.

Where is the time? As if walking with your pathetic shrine all day is not tiring

enough, I cook and do all the housework. The girls will not help and you just sit

outside smoking your beedi. How much do you expect one woman to do?

Dont start complaining now. Do we have chillies for the gruel? Go, bring me some

quickly.

***

Amma! Amma! cried Nallappa hoping that there would be at least one elderly

person in the house. The house was big. In Nallappas mind, big houses meant

disproportionately big problems and hence generous offerings to the Baba.

A young boy of ten looked out through the railings that half-heartedly tried to form

themselves into a gate. What do you want?

I am going on a Pilgrimage to Shirdi. Are there any offerings I could take? Are there

any adults in the house? Where is your mother?

Why is the music from your rickshaw so loud?

It is not a rickshaw. It is Sai Babas shrine. Are there any adults in the house?

Amma!

Why is the music from Sai Babas shrine so loud? asked the domineering

conversationalist.

How else will everyone in the street know when Baba enters? Nallappa asked back,

indignation gaining an upper hand over sugary sweetness.

But it is awfully loud. I am getting a headache. What is the point of playing it so

loud? You are going to ride through the whole street anyway. I am getting a

headache. The boy pinched his eyelids together and grimaced.

Oye here! Reduce the volume. Little master here is not keeping well, said Nallappa

to his wife, casually misrepresenting facts; she stolidly fidgeted with knobs and

brought the volume down, only after momentarily turning it up startling already

nervous birds in the neighbourhood.

That is better. So, why are you going to Shirdi?" asked the boy.

To carry peoples offerings and to pray for their profuse welfare," rattled off

Nallappa becoming impatient.

So, Amma asked you to come?

No, no. said Nallappa, indignation morphing into a species of irritation. I will be

going to Shirdi anyway. I am merely here to ask if your mother has any offerings that

I can carry for you.

Why do you want to carry peoples offerings?

To help people. Baba helps me, if I help others.

Unconvinced, the boy hesitated for a moment. He then turned around and went into

the house. He returned with his mother.

Nallappa! you are here finally! I knew Baba would send you soon.," said the boys

mother animatedly as she opened the gate. The last time you took our offering to

Shirdi, my husband got promoted at his work in less than a week! A miracle! The

boy had lost interest by now and was trying to balance a big smooth pebble on top of

a tiny serrated rock.

It is all Babas grace Amma. I am simply a messenger.

When are you going again? I have some clothes and money. This time I have vowed

to feed five beggars. Leaving the gate open, the boys mother went inside to fetch

Nallappas cargo.

***

Swamiji, where are you traveling to? Nallappa asked cautiously.

A bearded gent in ochre robes rearranged his face instantly into a smile that hinted

that he had been expecting the question all alongafter all, they were alone in this

compartment of the train. Haridwar, I go there every six months. One needs to wash

ones sins away, eh? But then, one starts accumulating sins even on the journey back

home from Haridwar. These sins, how pernicious they are, how capricious.

Nallappa was silent, he did not want offend his Swamiji by claiming to understand

deep mysticism such as this.

How about you? asked the gent.

Shirdi, Swamiji. I go there every three months.

The gent quenched conversation by looking out the barred window, his long hair

seeming to register protest against this act by dashing away in the opposite direction.

Do you want to know what I do for a living, Swamiji?

Do you want me to know? said the gent enigmatically.

Swamiji, I collect peoples offerings, submit them to Baba and pray that he blesses

them profusely in return.

You have no other job?

No, Swamiji.

Do you have a family?

Yes, Swamiji. One wife and two daughters.

How do you feed them without a job? You dont look like someone with a big

inheritance?

Whatever I collect from people I take forty percent as Babas blessing to this poor

soul. I even pay for my travel to Shirdi and accommodation from that forty percent.

The rest I offer to Babas feet. The forty percent feeds me and my family. It is barely

sufficient for us. You know, with two daughters and todays inflation, just forty

What? interrupted the gent unceremoniously. That is preposterous. You will rot in

hell for this.

A startled Nallappa said cautiously, But Swamiji

Also, the beedi you were smoking at the station - that will steep you in snake pit of

cancer. Over and over we are born and over and over are we killed. What you are

doing will entrench you further in this horrendous cycle of samsara. Find a decent

job. Leave the saint alone.

That night, the gent slept the sleep of an honest man who has withheld nothing.

***

This infernal coughing is getting worse. Sometimes I even cough blood. What are

you putting in my food nowadays? Sawdust instead of chilli powder to save money?

Your cooking has become pathetic.

This accusation made his wife livid. Stop this nonsense, you slob. It must be the

beedi you smoke all the time.

Dont take away the only pleasure I have, please. It must be the food. Check if there

are insects in the kitchen. I saw a grotesque lizard there just yesterday.

I wont," said his wife flatly. In any case, do you remember the loan we took from

mama? He has waited so long only because he is my moms brother. But now, he

wants his money back by the end of this week.

Where is the money? asked Nallappa helplessly.

We need to find it. I will lose my familys respect otherwise. You dont want them to

think that you are no-gooder either, do you? taunted his wife.

If he wants something by next week, I can only think of taking money from Babas

offerings," said Nallappa and laughed. But of course, that is unthinkable," he

teetered.

His wife capitalised on this pregnant equivocacy. Why? We can always replace the

money. Also, who would really care if you did not go to Shirdi? Baba will understand.

Helping the poor is helping God. We desperately need this money. Without meeting

his eye, she got up, went to the fridge and brought him some ice cream.

What flavour is this? asked Nallappa.

Butterscotch. The girls like it a lot.

Hmit is good. Let us take the money out tonight. I think we should repay mamas

loan immediately. I wont go to Shirdi this time. Baba is merciful, he will

understand.

***

Amma! Amma! crowed Nallappa.

The boy recognised Nallappa and called out to his mother.

You did not bring back any prasad from your last trip, accused the boys mother.

How was it? she asked trying to produce an aftertaste of curiosity.

I had an unfortunate trip. On my way back, I lost all my belongings including the

prasad in the train. I know how much prasad means to devotees, they are physical

manifestations of Babas blessings. I have known children being cured of deadly

diseases after eating just a handful of the rock sugar. I dont know why Baba is testing

me like this. Nallappa began to intently follow the track of an ant carrying a piece of

what looked to him like jaggery on its back.

Oh, that is not good! Did you lose any valuables? Do you need any money? asked

the boys mother, as if still trying to plaster with copious amounts of concern, the dent

of her original accusation.

No, Amma. It is the prasad that I am feeling bad about. The ant had dropped its

putative jaggery and was trying to pick it up again.

Dont worry about that. It is all right. When are you going back again?

In a week.

All right, I will bring some money. Wait a minute.

As he was waiting, Nallappa suddenly became conscious of the small boy who was

staring at him from behind the bars of the closed gate. Even though it had been only

three months, it seemed to Nallappa as if the boy had grown over two feet.

***

Madras Central Station was crowded. Nallappa was sitting on his berth, looking

through the barred window at his wife who was standing on the platform, resting her

forehead of the bars of the window.

I am sorry that I cannot come this time.

Oh, that is all right. We need to start saving more money. The girls will have to be

married off soon.

They are only fifteen. We should wait for five more years, protested his wife.

Nallappa was looking intently at a train that was just pulling into the station. Initially,

it produced a pinching shriek that degenerated progressively into a chugging quiet. I

dont feel comfortable waiting that long. It is good to get everything over soon.

Especially with my health

You are a pathetic hypochondriac. You are just fine. Mama said that coughing blood

is quite common at your age. You have not yet stopped smoking beedi.

Nallappa sighed.

Have you packed all the offerings? asked his wife. She strained her toes to extend

her height after which she strained her eyes trying confirm the existence of a bundled

cloth bag.

Yes," confirmed Nallappa. I will be back in a week.

You should buy a cellphone. It will be easier for me to keep in touch, now that you

are going to travel by yourself mostly.

Okay. The fans have started spinning. The train will leave soon. You go home and

take care of the girls. His wife seemed not to hear; she was intently looking at

someone who, she whisperingly conjectured, was a film actor. Nallappas train began

to chug out of the station. The actor had disappeared.

***

Nallappa was coming out of the temple, peoples offerings duly handed over to the

Babas feet. He was wearing a white shirt decorated with haphazardly splashed rust

red. He started walking to Shirdi railway station.

Give me something to eat, master. I havent eaten anything for a week. A beggar,

whose cloak smelt of rancid meat, was approaching him. Stray dogs were following

him with an eagerness that suggested that at least some of the food donated to him

percolated down to them.

I dont have anything. I will give you something next time. Take your beggary

elsewhere. Nallappa turned away from the beggar to look at the temple. He

perfunctorily tilted his head downwards in symbolic obsequiousness. Usually, he

liked to catch a glimpse of the shrine before turning left into a lane with high-rise

apartment buildings that entirely hid the temple. Shaped like a giant funnel, the temple

dome appeared whiter than usual. He wondered whether it had been polished recently.

I cannot wait master. Might not be alive," said the beggar jolting Nallappa out of his

reverie. Nallappa turned around and almost crashed into the beggars scraggy and

hirsute chin. Without lifting his head, Nallappa apologised to the beggars thighs,

sidestepped, and continued walking.

But master, I cannot wait," persisted the beggar.

What? Who are you? What do you want? asked Nallappa with good-natured

curiosity.

Master, I said I cannot wait.

Wait for what? Nallappa resumed walking.

Wait until you come back next time," said the beggar, now walking at Nallappas

side. The dogs sauntered a few feet behind him.

Why do you have to wait for me? I never asked you to.

For a moment the beggar hesitated, trying to decide whether recapitulation or renewal

might be the best strategy to resuscitate this conversation. Can you give me

something to eat? I havent eaten anything for a month," he renewed, his deprivation

inflated from a week to a month within the span of two minutes.

I do not have anything now. Ill give you something the next time I come.

But master, I cannot wait. Might not be alive. said the beggar, not altering the line

of his pitch.

Nallappa froze. His body became still, eyebrows the only moving parts. His eyes

became unfocussed. The beggar, informed by his copious worldly experience,

resigned and began walking away.

Here, take my bag, whispered Nallappa.

Master? asked the beggar dubiously.

Here, take my clothes, sell them, wear them, do whatever makes you happy! said

Nallappa, almost screaming. He thrust his cloth bag into the beggars arms which

instinctively grasped it.

The beggar hesitated for a moment as he digested this unprecedented reaction.

Master is angry with me. I do not want anything. Here, take your bag back.

Nallappa stood still with folded hands and stared blankly.

Master wants to punish me. Please take your bag back, beseeched the beggar.

Nallappa continued to stare blankly.

The beggar, now a nervous wreck, looked around frantically to find an arbitrator. He

saw a small crowd in a tea stall by the road. Just as he began walking towards them,

Nallappa sprinted in the direction of the railway station.

***

There was no one else in Nallappas compartment. Now shorn of his luggage, he

stretched himself out on his berth. Resting the back of his head on his palms, he

crossed his feet and desultorily stared through the barred window. As the train picked

up speed, time compressed space, rending objects into a hypnotic visual concoction

that was engrossing as kaleidoscope but devoid of meaning. He began reminiscing

about how he sat on top of a goods train on his first trip to Madras, about how the

view from the top of a train was very different from the view through its window,

about how he would sell tea in trains in his errand boy days, about how when a

compartment was empty, he would sit by the window, press his face against the metal

bars and count trees as the train throttled along, about how someone stole his purse,

about how the kind ticket inspector loaned him some money and saved him from

caning, about how the blind beggar sat next to the lavatory and sang delightful songs.

By the time the train had reached the next railway junction, a sleep that had eluded

Nallappa until now, finally enveloped him.

You might also like

- The Characteristic Features of Indian Culture Have Long Been A Search For Ultimate Verities and The Concomitant DiscipleDocument3 pagesThe Characteristic Features of Indian Culture Have Long Been A Search For Ultimate Verities and The Concomitant DisciplePrince bhaiNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Hard WorkDocument7 pagesThe Importance of Hard WorkClare TrizNo ratings yet

- The Lotteries of Haji ZakariaDocument5 pagesThe Lotteries of Haji Zakariacharo bao-ilanNo ratings yet

- Lured To LaraliaDocument11 pagesLured To LaraliaNausikaDalazBlindazNo ratings yet

- All The Ten Stories FinalDocument56 pagesAll The Ten Stories FinalKaramchedu Vignani VijayagopalNo ratings yet

- Aen 1semesterDocument14 pagesAen 1semesterANNISHA SEBASTIAN 2131228No ratings yet

- Two NovelsDocument6 pagesTwo NovelsNauman MashwaniNo ratings yet

- Our Duty Toward Our ParentsDocument5 pagesOur Duty Toward Our ParentsShani Ahmed SagiruNo ratings yet

- RebatiDocument15 pagesRebatiAjay Ashok0% (1)

- Sai Satcharitra: Sai Satchritra - Chapter XXIXDocument6 pagesSai Satcharitra: Sai Satchritra - Chapter XXIXayush_ruiaNo ratings yet

- Her Journey Within - Preview ChapterDocument38 pagesHer Journey Within - Preview ChapterViraj KulkarniNo ratings yet

- Rocking-Horse-Winner Short StoryDocument13 pagesRocking-Horse-Winner Short StoryFlorenciaNo ratings yet

- Shirdi Sai BabaDocument26 pagesShirdi Sai BabaBharath TrichyNo ratings yet

- A Time of Waiting by Clare WestDocument63 pagesA Time of Waiting by Clare WestZakaria EL KHILANINo ratings yet

- Lost SpringDocument12 pagesLost SpringAkashNo ratings yet

- English Practicum Pesut MahakamDocument9 pagesEnglish Practicum Pesut Mahakamdinda nikmatulNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 2. Lost Spring - WatermarkDocument6 pagesChapter - 2. Lost Spring - WatermarkFaizan AnsariNo ratings yet

- Lit 3 Module 14 The Beautiful HorseDocument4 pagesLit 3 Module 14 The Beautiful HorseDominick AlbisNo ratings yet

- Yes! It Is The Right ThingDocument2 pagesYes! It Is The Right ThingFaheem MushtaqNo ratings yet

- Faith Under Water: A Gripping True Account of Flooding Disasters and Escaping Slavery and Organized Crime in Dhaka, Bangladesh: True stories of climate change refugees, #1From EverandFaith Under Water: A Gripping True Account of Flooding Disasters and Escaping Slavery and Organized Crime in Dhaka, Bangladesh: True stories of climate change refugees, #1No ratings yet

- 06 Story StiffnessDocument2 pages06 Story StiffnessDigvijay GiraseNo ratings yet

- Design and Assembly Analysis of Piston, Connecting Rod & CrankshaftDocument12 pagesDesign and Assembly Analysis of Piston, Connecting Rod & CrankshaftD MasthanNo ratings yet

- Recruiting Test General KnowledgeDocument15 pagesRecruiting Test General KnowledgeRelando Bailey84% (174)

- When A Migraine OccurDocument9 pagesWhen A Migraine OccurKARL PASCUANo ratings yet

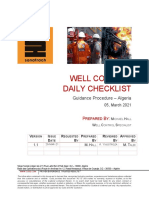

- Well Control Daily Checklist Procedure VDocument13 pagesWell Control Daily Checklist Procedure VmuratNo ratings yet

- 9 Cartesian System of CoordinatesDocument15 pages9 Cartesian System of Coordinatesaustinfru7No ratings yet

- Report NovelDocument12 pagesReport NovelHasan Moh'd Al AtrashNo ratings yet

- PSR-S700 S900 Lsi CDocument13 pagesPSR-S700 S900 Lsi CAdriano CamocardiNo ratings yet

- Fusibles NHDocument4 pagesFusibles NHPaul SchaefferNo ratings yet

- NU632 Unit 4 Discussion CaseDocument2 pagesNU632 Unit 4 Discussion CaseMaria Ines OrtizNo ratings yet

- An Open Letter To Annie Besant PDFDocument2 pagesAn Open Letter To Annie Besant PDFdeniseNo ratings yet

- Hot Vibrating Gases Under The Electron Spotlight: Gas MoleculesDocument2 pagesHot Vibrating Gases Under The Electron Spotlight: Gas MoleculesRonaldo PaxDeorumNo ratings yet

- BS en 480-6-2005Document5 pagesBS en 480-6-2005Abey Vettoor0% (1)

- Manitou Forklift MLT 845 Part ManualDocument22 pagesManitou Forklift MLT 845 Part Manualedwardgibson140898sib100% (16)

- Nutritional and Antinutritional Composition of Fermented Foods Developed by Using Dehydrated Curry LeavesDocument8 pagesNutritional and Antinutritional Composition of Fermented Foods Developed by Using Dehydrated Curry LeavesManu BhatiaNo ratings yet

- BS 5655-14Document16 pagesBS 5655-14Arun Jacob Cherian100% (1)

- Sulphur VapoursDocument12 pagesSulphur VapoursAnvay Choudhary100% (1)

- Sheet Service - SKT80SDocument3 pagesSheet Service - SKT80SAnanda risaNo ratings yet

- Hydro PDFDocument139 pagesHydro PDFVan Quynh100% (2)

- Okuma GENOS M560R-V TECHNICAL SHEET (4th Edition)Document79 pagesOkuma GENOS M560R-V TECHNICAL SHEET (4th Edition)Ferenc Ungvári100% (1)

- Australian Mathematics Competition 2017 - SeniorDocument7 pagesAustralian Mathematics Competition 2017 - SeniorLaksanara KittichaturongNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Ship Maintenance and Repair For Future Marine Engineers PDFDocument11 pagesFundamentals of Ship Maintenance and Repair For Future Marine Engineers PDFShawn Wairisal100% (2)

- LeachingDocument14 pagesLeachingmichsantosNo ratings yet

- Calvino - The Daughters of The MoonDocument11 pagesCalvino - The Daughters of The MoonMar BNo ratings yet

- Examination, June/July: ExplainDocument6 pagesExamination, June/July: ExplainSandesh KulalNo ratings yet

- Laboratory Department Tracking Sheet OriginalCHARM2Document128 pagesLaboratory Department Tracking Sheet OriginalCHARM2Charmaine CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Soil Resources Inventory For Land Use PlanningDocument9 pagesSoil Resources Inventory For Land Use PlanningmehNo ratings yet

- Anatomy ST1Document2 pagesAnatomy ST1m_kudariNo ratings yet

- Srotomaya Shariram: Dr. Prasanna N. Rao Principal, SDM College of Ayurveda, Hassan-KaranatakaDocument21 pagesSrotomaya Shariram: Dr. Prasanna N. Rao Principal, SDM College of Ayurveda, Hassan-KaranatakaDrHemant ToshikhaneNo ratings yet

- TNSTCDocument1 pageTNSTCMohamed MNo ratings yet