Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Establishing Standards: Mathematical Practice

Uploaded by

api-256960061Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Establishing Standards: Mathematical Practice

Uploaded by

api-256960061Copyright:

Available Formats

532 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL Vol. 19, No.

9, May 2014

h

in which students create their own

solutions to problems, critique the

reasoning of their peers, and come

to a consensus on viable mathemati-

cal strategies and solutions (CCSSI

2010). However, these Standards for

Mathematical Practice (SMP) are

difcult for most middle school stu-

dents to enact, and CCSSM gives no

information on how to help students

embody these practices. This article

outlines some teaching strategies from

A grocery shopping

problem can link

the Common Cores

standards with a

new classroom

culture.

Michelle L. Stephan G

E

O

R

G

E

D

O

Y

L

E

/

T

H

I

N

K

S

T

O

C

K

(

3

)

Have you ever tried to get a middle

school student to explain her reason-

ing in front of her peers? In your

attempts to have students understand

one anothers reasoning, how many

times have you heard, I dont get it!

Any of it! And how do your middle

school students react when someone

makes a mistake? Common Core

State Standards for Mathematics

(CCSSM) expects teachers to estab-

lish problem-solving environments

ESTABLISHING STANDARDS

MATHEMATICAL PRACTICE

F

O

R

Copyright 2014 The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc. www.nctm.org. All rights reserved.

This material may not be copied or distributed electronically or in any other format without written permission from NCTM.

Vol. 19, No. 9, May 2014 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL 533

my own middle school mathemat-

ics classes in an attempt to help my

students implement the SMP.

One particular school year, I

videotaped my eighth-grade class

during the rst two weeks of school.

The purpose was to document the

strategies that enabled students to

problem solve and to discuss their

solutions without fear of embarrass-

ment. CCSSM was not yet adopted,

so research on social norms guided the

development of my teaching practice.

Social norms are the expectations that

the teacher and students have for each

other regarding ways of participat-

ing in classroom discussions. These

social norms, the most prominent in

Standards-based classrooms, expect

students to

1. explain their reasoning to others;

2. indicate agreement or disagreement;

3. ask clarifying questions when they

do not understand; and

4. attempt to understand the reason-

ing of others (Cobb et al. 1992;

Stephan and Whitenack 2003).

These social norms align with many

of the SMP, particularly the stan-

dards of making sense of problems

and persevering in solving them

(SMP 1), reasoning abstractly and

quantitatively (SMP 2), and con-

structing viable arguments and

ESTABLISHING STANDARDS

MATHEMATICAL PRACTICE

534 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL Vol. 19, No. 9, May 2014

critiquing the reasoning of others

(SMP 3). The excerpts that follow

contain details of some of the strate-

gies I have developed to make these

SMPs and social norms come alive in

my middle school classroom.

SPECIFIC TECHNIQUES

The rst two weeks of the school

year were committed to setting social

norms through general problem solv-

ing (SMP 1). For example, the prob-

lem that students encountered when

they entered my classroom for the rst

time is shown in gure 1.

At the beginning of the rst day of

class, the eighth graders were greeted

as they walked in. They were then

asked their names and asked to sit

next to a person who they thought

would be helpful during math class.

They were also told to try the prob-

lem on the whiteboard. Because stu-

dents had studied ratio and propor-

tions in the seventh grade, I expected

this problem to be accessible to all

students, including those who were

identied with special needs.

As students were problem solving,

I monitored their work in a fashion

similar to that described in 5 Practices

for Orchestrating Mathematics Discus-

sions (Smith and Stein 2011). During

my monitoring time, students were

encouraged to write their thinking

on paper and to talk with a peer

when they were stuck (SMP 1). I

also gathered information on how

students solved the problem so that I

could select students who had solution

processes that would be helpful for the

follow-up class discussion.

Because of my agenda of establish-

ing social norms, students presented

their ideas in a specic sequence. For

example, Brianna went rst because

her solution method was highly

computational and would need deeper

explanation for other students to un-

derstand. Her presentation would give

the class the opportunity to discuss the

importance of explaining and asking

questions. The six strategies that fol-

low guide the establishment of social

norms for productive problem solving.

Strategy 1: State Expectations Early

That opening period would be the

rst whole-class discussion of the year,

so it was critical to use it to begin the

process of developing the norms that

would drive the students for the rest of

the year. Therefore, I engaged them in

a discussion about ways to participate

in the upcoming discussion. They were

told that their job is to listen. When

students were prompted to explain

why, Anders responded, You might

like their ideas. To this statement, I

added the following comments:

You might like their ideas. And

then you should steal it, right? Steal

their ideas? Thats why I want you

to listen. Im going to be asking you

when somebodys up here presenting,

Arthur, I want you to be listening,

trying to understand their way. What

if you didnt do it their way? Should

you try to understand their way? Or

just say, Who cares? They didnt do

it my way, I dont need to listen. No!

You need to listen because as Anders

just said, you might like their way

better, right?

I also added this comment:

Im going to be asking you questions.

Lets say that Brianna is up here ex-

plaining. Im going to ask someone to

explain what Brianna just did. And if

you cant, you need to ask a question.

The expectation that students should

listen to others explanations was explic-

itly outlined. I asked them specically

what their job is when someone is ex-

plaining, then solicited reasons why this

was important. However, if the SMP of

analyzing and critiquing other students

arguments is going to become routine,

stating these expectations upfront is not

enough. Teachers must hold students

accountable for listening, so I stated my

accountability technique: I am going to

call on students to explain what another

student just argued.

Strategy 2: Hold Students

Accountable for Explanations

To begin the whole-class discussion,

Brianna came to the board to explain

her approach to solving the Bacon

problem in gure 1. At this prompt,

Brianna realized I was expecting more

than just an oral presentation from

her desk. Our class conversation can

be found in gure 2. I again called on

the class to anticipate the rationale for

certain expectations. Arthur argued

that it is easier for the speaker just to

read it, so I asked about the needs of

the audience. Anders explained that

it would be easier for the audience to

understand if Brianna wrote some-

thing, and she complied (see g. 3).

As Brianna wrote her process on

the board, I challenged the students to

see if they could gure out her reason-

ing while she wrote it. This was my

way of communicating to students that

they should be analyzing Briannas

Drake found a sale on bacon at the Winn-Dixie. They were selling 4 packages

for $10.

How much would Drake pay for 6 packages?

How much would he pay for 1 package?

Fig. 1 Solving the Bacon problem, the frst task of the school year, sets the stage for

the forms of conversations that students can expect throughout the year.

Vol. 19, No. 9, May 2014 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL 535

work and attempting to understand it

(SMP 3). I paused for a few seconds

of thinking silence and asked Brianna

to move to the side so that everyone

could analyze her written argument

(SMP 3). The statements, I think

were ready and Can you explain . . .

to everybody, rather than I think I am

ready or Can you explain . . . to me?

are ways to let students know that the

purpose of explaining is for the students

to analyze and verify solutions, not just

the teacher.

As a result of this prompting,

Brianna said:

I knew that 4 packages was $10.00.

So I did 4 divided by $10.00 and got

$2.50, so one package was $2.50.

And then I knew I had to get 6

packages so I added the four and one

was $2.50 plus $2.50 was $5.00. And

$10.00 plus $5.00 is $15.00.

Strategy 3: Hold Students

Accountable for Asking Questions

The computational explanation given

by Brianna did not contain an indica-

tion of what her steps and the results

meant, so I searched the room to see

what sense students had made of her

work. I asked students to indicate

whether they agreed or not by

asking:

Could you re-explain it? [They

indicated yes.] Hold your hand up

if youve got a question. Before she

escapes [sits down], anybody got a

question for her? That means if I call

around, youll know, youll be able to

explain her way, right? Alright. Im

going to call around. Valerie, youre

her partner. Whatd she do, howd

she solve this one?

Valerie responded, I dont know.

Because Briannas explanation was

very procedural (see Thompson et al.

1994), many students probably did not

connect why she added $2.50 twice to

$10.00. This procedural explanation

gave me the opportunity to hold stu-

dents accountable for asking questions

when they did not understand. I let

students know that I was about to ask

others to re-explain Briannas solution

method. As expected, no one raised a

hand, so I called on Valerie to re-

explain. When she admitted she could

not, I took this time to re-iterate my

expectation that students should raise

their hand if they do not understand.

Does anyone have a question? is a

weak way to hold students accountable

because they can answer yes and the

teacher moves on. The teacher should

follow up and ask specic people to

re-explain; if they cannot, reiterate the

expectation.

Strategy 4: Hold Students Accountable

for Making Sense of Solutions

Asking questions is important for

helping students understand others

solutions, but the teacher must help

students know what questions to ask.

Most students give very calculational

explanations (i.e., the steps that were

taken) for their solutions (Thompson

et al. 1994). The teachers role is to

push students toward more conceptual

explanations in which the student ex-

plains why a particular calculation was

made and what the results of that cal-

culation mean in terms of the quanti-

ties in the problem situation (SMP 2).

Thompson and others (1994) contend

that conceptual explanations are more

benecial for struggling students

Brianna: Oh, I have to write it, too?

Teacher: Well, what do you guys think? Should she write something on the

board, or should she just read it from her paper?

Arthur: Its easier to read it from your paper than write it.

Teacher: It is easier when youre the speaker. Right, Hugo? To just speak it

from your paper? What about if youre the person listening? Whats easier

for you if youre trying to learn?

Anders: Its easier [for the listener] to read it.

Teacher: Its easier to read it, Anders says. So what do you think? Whats

your advice to her? Should she write something down for you to read?

Students: Yeah!

Fig. 2 This conversation demonstrates how the explain-your-thinking expectation

became the norm.

Fig. 3 At the request of classmates, Brianna demonstrated her reasoning by writing the

explanation on the board.

536 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL Vol. 19, No. 9, May 2014

because the reasons behind the steps

are revealed to them.

To begin the sample discussion

in gure 4a, Jamie simply restated

the steps that he used to solve the

problem. To press for understanding,

I asked Judson what the numbers on

the top stood for, so that students

could draw connections to the quanti-

ties in the Bacon problem. As a result,

Mariana brought out the term unit

rate, and Marta related to students

what that meant in this situation.

Strategy 5: Hold Students

Accountable to Question What

They Do Not Understand

Often when students do not un-

derstand the explanation of another

student, the teacher presses them to

ask a question. At the beginning of

the school year, the most frequent

response in my class is I dont get

it! Any of it. How does a teacher

handle this exclamation without

re-explaining everything in his or

her own words? How can we teach

students how to identify their areas of

misunderstanding?

As the dialogue in gure 4a

continued, Keisha responded that

she really did not understand Jamies

solution. In the subsequent exchange

with Keisha, shown in gure 5, I at-

tempted to model how a student can

go through the steps of the process

and how to ask themselves, Do I

understand this part? As it turned

out, Keisha was able to explain almost

all the steps except when misread-

ing Jamies writing as 250 rather than

2.50. Such a misinterpretation caused

her difculty in making sense of the

rest of the solution. Helping to nd

the misunderstanding was an effec-

tive strategy when students indicated

that they did not understand an

entire solution. With enough of these

explicit conversations, students began

to analyze others solutions to nd

specic places about which they could

Teacher: Oh, what part dont you get?

Keisha: The whole thing.

Teacher: Oh no! The whole thing! Lets start here. Do you understand that part?

Keisha: Uh, 4 over 10? That four, that four packages cost $10.00.

Teacher: You understand it, that part! [with excitement] Whats this part all

about, Keisha? See if she can get it. I bet she can, dont you? Whats that

next part all about?

Keisha: Does it say 250?

Anders: Thats 2 point 50.

Keisha: Oh! That one pack costs $2.50.

Teacher: And then what? Whats this stand for?

Keisha: Thats one package, and it costs $2.50.

Teacher: Uh-huh. Whats this stand for?

Keisha: 6 packages and $15.00?

Teacher: Uh-huh.

Jamie: OK, so when I frst looked at the problem, it said that 4 packages was

$10. So 4 and 10. And then I tried to get to 1. I divided 4 by 4 to get 1

and 10 by 4 to 2.50. Then I did 1 times 6 to get 6 and then 2.50 times

6 to get to 15 [see g. 4b].

Teacher: Alright; Judson, what do these numbers on the top stand for in the

problem, for Jamie? What are they standing for?

Judson: The number of packages.

Teacher: How many packages? Mariana, what were you gonna say?

Mariana: Wouldnt it be like fnding the unit rate?

Teacher: Woo! Did you hear that? What do you think? That was kind of

directed at you [class]? What did she just ask? What did Mariana just ask?

[No one raises their hand.] Oh no! All listen. Mariana, ask again real loud.

Mariana: Wouldnt that be fnding the unit rate?

Marta: That one package costs 2.50.

Teacher: That one package costs 2.50. There it is. And then you used that

unit rate, Jamie, to fnd out how much 6 packages cost. What do you

think about Jamies way?

(a) Class discussion

(b) The calculations in Jamies strategy

Fig. 4 In this discussion, the teacher pushed the students to expound on the calculations.

Fig. 5 In this excerpt, the teacher helped students push through and reach understanding.

Vol. 19, No. 9, May 2014 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL 537

have made them. The class applauded

each person who presented and

congratulated students on listening

and being able to re-explain students

arguments. I also stated that we had

some work to do asking questions

when students do not understand one

another. However, we would begin

working on that more during the next

class period.

ESTABLISHING

NORMS TAKES TIME

The objective of this article was to

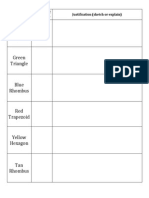

describe the strategies (see g. 6) for

establishing social norms that are

consistent with CCSSMs Standards

for Mathematical Practice. A class-

room environment in which students

persevere in solving problems and

feel engaged and safe enough to

explain their thinking to their peers

can have a positive effect on their

learning (Tarr et al. 2008). However,

social norms for communicating

productively in class do not arise fully

formed on the rst day of class. It

takes weeks for the teacher and stu-

dents to establish these norms and for

them to become stable for the rest of

the school year. For this reason, I do

not attempt to establish every single

norm on the rst day.

I reserve the rst two weeks for

building strong social norms and

SMPs. Two weeks is not only a rea-

sonable time period but also essential

for setting the stage for communica-

tion in later units that target specic

content. I recommend using general

mathematics problems that elicit

a variety of strategies and are not

focused on developing new knowl-

edge in a particular domain. Doing so

allows the teacher to focus his or her

attention explicitly on establishing

ask questions rather than say they

misunderstood the entire solution.

Strategy 6: Praise Students for

Their Participation and for Providing

Informative Feedback

To end the rst discussion of the

school year, it is extremely important

to stop in a similar manner as started:

being explicit about expectations for

current and future participation. This

helps students understand the char-

acteristics of their participation that

were acceptable in class and those that

needed to be improved. In addition, it

is important to point out which social

norms and Standards for Mathemati-

cal Practice were not acted on very

well. For example, at the close of the

Bacon problem, students were praised

for their willingness to present their

arguments in front of their peers,

acknowledging how nervous it might

Participating in NCTMs Member Referral Program is fun, easy,

and rewarding. All you have to do is refer colleagues, prospective

teachers, friends, and others for membership. Then as our

numbers go up, watch your rewards add up.

Learn more about the program, the gifts, and easy ways

to encourage your colleagues to join NCTM at

www.nctm.org/referral. Help others learn of

the many benets of an NCTM membership

Get started today!

NCTMs Member Referral Program

Help Us Grow Stronger

I NSPI RI NG TEACHERS. ENGAGI NG STUDENTS. BUI LDI NG THE FUTURE.

538 MATHEMATICS TEACHING IN THE MIDDLE SCHOOL Vol. 19, No. 9, May 2014

problem-solving norms rather than on

developing students knowledge of one

particular mathematics concept.

CCSSM Practices in Action

SMP 1: Make sense of problems and

persevere in solving them.

SMP 2: Reason abstractly and

quantitatively.

SMP 3: Construct viable arguments

and critique the reasoning of others.

REFERENCES

Cobb, Paul, Terry Wood, Erna Yackel,

and Betsy McNeal. 1992. Charac-

teristics of Classroom Mathematics

Traditions: An International Analysis.

American Educational Research Journal

29: 573604.

Common Core State Standards Initia-

tive (CCSSI). 2010. Common Core

State Standards for Mathematics.

Washington, DC: National Governors

Association Center for Best Practices

and the Council of Chief State School

Ofcers. http://www.corestandards

.org/wp-content/uploads/Math

_Standards.pdf

Smith, Margaret S., and Mary Kay

Stein. 2011. 5 Practices for Orchestrat-

ing Mathematics Discussions. Reston,

VA: National Council of Teachers of

Mathematics.

Stephan, Michelle, and Joy Whitenack.

2003. Establishing Classroom Social

and Sociomathematical Norms

for Problem Solving. In Teaching

Mathematics through Problem Solving:

PrekindergartenGrade 6, edited by

Frank K. Lester, pp. 14962. Reston,

VA: National Council of Teachers of

Mathematics.

Tarr, James E., Robert E. Reys, Barbara J.

Reys, scar Chvez, Jeffrey Shih, and

Steven J. Osterlind. 2008. The Impact

of Middle-Grades Mathematics

Curricula and the Classroom Learning

Environment on Student Achieve-

ment. Journal for Research in Math-

ematics Education 39 (May): 24780.

Thompson, Alba G., Randolph A. Philipp,

Patrick W. Thompson, and Barbara

A. Boyd. 1994. Calculational and

Conceptual Orientations in Teaching

Mathematics. In Professional Develop-

ment for Teachers of Mathematics, 1994

Yearbook of the National Council of

Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM),

edited by Douglas B. Aichele and

Arthur F. Coxford, pp. 7992. Reston,

VA: NCTM.

Any thoughts on this article? Send an

e-mail to mtms@nctm.org.Ed.

Michelle L. Stephan, michelle.stephan@

uncc.edu, is a former middle school math-

ematics teacher who now works as an

assistant professor of mathematics educa-

tion at the University of North Carolina

at Charlotte. She works with elementary,

middle, and high school mathematics

preservice teachers and is interested in

designing inquiry mathematics materials

for all students.

Strategy 1: State expectations before the rst explanation occurs

The teacher

states his or her expectations explicitly before a whole-class discussion

begins; and

engages students in developing the rationale for some of the norms.

Strategy 2: Hold students accountable for explaining

The teacher

calls on as many students as possible and uses names on day one;

calls on students by name to explain their reasoning; and

expects students to explain both verbally and in written form while

engaging students in understanding the rationale.

Strategy 3: Hold students accountable for asking questions

The teacher

calls on students by name to see if they have questions;

asks students to re-explain a solution method; and

reiterates that it is unacceptable to violate certain norms (e.g., not

asking a question when they do not understand).

Strategy 4: Hold students accountable for making sense of solutions

The teacher

asks students to not only re-explain but also describe why the particular

procedures were taken and what the results mean in terms of the situation.

Strategy 5: Hold students accountable to question what they do not

understand

The teacher

does not accept students claims that they do not understand the entire

solution explanation and instead teaches them how to analyze the strategy

to fnd the misunderstanding.

Strategy 6: Praise students for their participation and for providing

informative feedback

The teacher

applauds students for meeting norm expectations and provides feedback

when certain norms are not being met effectively.

Fig. 6 This listing describes strategies for establishing standards-based social norms in

math class.

NCTM Proudly Presents

INSIDE

Effective Teaching

and Learning

Essential Elements

Access and Equity

Curriculum

Tools and Technology

Assessment

Professionalism

Taking Action

Principles to Actions:

Ensuring Mathematical

Success for All

What it will take to turn the opportunity of the

Common Core into reality in every classroom,

school, and district.

Continuing its tradition of mathematics education leadership, NCTM

has undertaken a major initiative to dene and describe the principles

and actions, including specic teaching practices, that are essential for

a high-quality mathematics education for all students.

This landmark new title offers guidance to teachers, mathematics coaches,

administrators, parents, and policymakers:

Provides a research-based description of eight essential Mathematics

Teaching Practices

Describes the conditions, structures, and policies that must support the

Teaching Practices

Builds on NCTMs Principles and Standards for School Mathematics

and supports implementation of the Common Core State Standards

for Mathematics to attain much higher levels of mathematics

achievement for all students

Identies obstacles, unproductive and productive beliefs, and key

actions that must be understood, acknowledged, and addressed by all

stakeholders

Encourages teachers of mathematics to engage students in

mathematical thinking, reasoning, and sense making to signicantly

strengthen teaching and learning

www.nctm.org/PrinciplestoActions

April 2014, Stock #14861

List Price: $28.95 | Member Price: $23.16

SAVE 25%! $21.71

Use code MTMS514 when placing order.

Offer expires 6/30/14.*

Also available as an

List Price: $4.99 | Member Price: $3.99

For more information or to place an order,

please call (800) 235-7566 or visit www.nctm.org/catalog.

Visit www.nctm.org/catalog for tables of content and sample pages.

NCTM Members Save 25%! Use code MTMS514when placing order. Offer expires 6/30/14.*

*This offer reects an additional 5% savings off list price, in addition to your regular 20% member discount.

4449-A nctm_MTMS_May2014_FullPage_PtA_rev1_Layout 1 4/1/14 1:56 PM Page 1

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 1st Grade Phonemic Awareness Phonics AssessmentDocument19 pages1st Grade Phonemic Awareness Phonics Assessmentapi-346075502No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Motivating Climate PLPDocument29 pagesMotivating Climate PLPclaire yowsNo ratings yet

- Least Learned Skills 2020 Grade 6Document7 pagesLeast Learned Skills 2020 Grade 6Kilitisan ESNo ratings yet

- English9 - q1 - Mod13 - Make A Connection Between The Present Text and Previously Read TextDocument15 pagesEnglish9 - q1 - Mod13 - Make A Connection Between The Present Text and Previously Read Text9 - Sampaugita - Christian RazonNo ratings yet

- A "Marketing Plan With A Heart" For:: St. Paul University Manila College of Business Management EntrepreneurshipDocument14 pagesA "Marketing Plan With A Heart" For:: St. Paul University Manila College of Business Management EntrepreneurshipPen PunzalanNo ratings yet

- Area of SquaresDocument10 pagesArea of Squaresapi-256960061No ratings yet

- NasamemosDocument3 pagesNasamemosapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Whats Your Angle Lab SheetDocument2 pagesWhats Your Angle Lab Sheetapi-256960061No ratings yet

- LostinspaceDocument4 pagesLostinspaceapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Rules For ToolsDocument1 pageRules For Toolsapi-256960061No ratings yet

- BackyardprojectDocument2 pagesBackyardprojectapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Dollar Wall PresentationDocument8 pagesDollar Wall Presentationapi-256960061No ratings yet

- PlanetaryfactsheetDocument1 pagePlanetaryfactsheetapi-256960061No ratings yet

- My Grid Paper Crop CirclesDocument4 pagesMy Grid Paper Crop Circlesapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Area 51 ProjectDocument1 pageArea 51 Projectapi-256960061No ratings yet

- FillingtheboxDocument3 pagesFillingtheboxapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Pythagorean TriplesDocument3 pagesPythagorean Triplesapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Crop Circles Journal CPDocument2 pagesCrop Circles Journal CPapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Task Sports BagDocument1 pageTask Sports Bagapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Area 51 AssessmentDocument2 pagesArea 51 Assessmentapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Triangular FrameworksDocument2 pagesTriangular Frameworksapi-256960061No ratings yet

- LessonplanningguidelinesDocument1 pageLessonplanningguidelinesapi-256960061No ratings yet

- PresentationguidelinesDocument1 pagePresentationguidelinesapi-256960061No ratings yet

- 02kwc FormDocument1 page02kwc Formapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Circles and SquaresDocument1 pageCircles and Squaresapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Security CameraDocument2 pagesSecurity Cameraapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Using Indirect Measurement Method CardsDocument4 pagesUsing Indirect Measurement Method Cardsapi-256960061No ratings yet

- 06bulleted Mathematical PracticesDocument2 pages06bulleted Mathematical Practicesapi-256960061No ratings yet

- 20sd3 2labsheetDocument1 page20sd3 2labsheetapi-256960061No ratings yet

- 16cs2 4Document1 page16cs2 4api-256960061No ratings yet

- Design Challenge II: D Aw GT Ang eDocument2 pagesDesign Challenge II: D Aw GT Ang eapi-256960061No ratings yet

- 01aembeddingbinderpp1 6fDocument6 pages01aembeddingbinderpp1 6fapi-256960061No ratings yet

- 05mathematical Practices With QuestionsDocument2 pages05mathematical Practices With Questionsapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Designing Triangles and Quadrilaterals: NotesDocument2 pagesDesigning Triangles and Quadrilaterals: Notesapi-256960061No ratings yet

- Progress Report 1 - Olivia Day - s5056250Document19 pagesProgress Report 1 - Olivia Day - s5056250api-375225559No ratings yet

- Establishing Strategic PayDocument17 pagesEstablishing Strategic PayRain StarNo ratings yet

- Student Learning MotivationDocument5 pagesStudent Learning MotivationAndi Ulfa Tenri PadaNo ratings yet

- Bugreport Lime - Global QKQ1.200830.002 2021 05 04 22 36 45 Dumpstate - Log 30853Document30 pagesBugreport Lime - Global QKQ1.200830.002 2021 05 04 22 36 45 Dumpstate - Log 30853Blackgouest 1043No ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - Ielts Reading in GeneralDocument28 pagesLesson 1 - Ielts Reading in GeneralTrangNo ratings yet

- Music 5 - Unit 1Document4 pagesMusic 5 - Unit 1api-279660056No ratings yet

- Circular Seating Arrangement Free PDF For Upcoming Prelims ExamsDocument14 pagesCircular Seating Arrangement Free PDF For Upcoming Prelims ExamsBiswapriyo MondalNo ratings yet

- Tips For Teaching Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of HearingDocument18 pagesTips For Teaching Students Who Are Deaf or Hard of HearingSped-Purity T RheaNo ratings yet

- Kasturi Ram College Digital Media Marketing Internship ReportDocument20 pagesKasturi Ram College Digital Media Marketing Internship ReportShreyan SinghNo ratings yet

- Personality Across Cultures: A Critical Analysis of Big Five Research and Current DirectionsDocument14 pagesPersonality Across Cultures: A Critical Analysis of Big Five Research and Current Directionsgogicha mariNo ratings yet

- Week 1 MTLBDocument7 pagesWeek 1 MTLBHanni Jane CalibosoNo ratings yet

- Philippine Constitution provisions on educationDocument2 pagesPhilippine Constitution provisions on educationLouise salesNo ratings yet

- Creating COM+ ApplicationsDocument7 pagesCreating COM+ ApplicationsAdalberto Reyes ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- Midterm - ED PCK 2Document18 pagesMidterm - ED PCK 2Cristine Jhane AdornaNo ratings yet

- PLMAT 2012 General Information Primer PDFDocument2 pagesPLMAT 2012 General Information Primer PDFemerita molosNo ratings yet

- Classified Ads for Teachers, Hairdressers and Other JobsDocument10 pagesClassified Ads for Teachers, Hairdressers and Other JobssasikalaNo ratings yet

- SK Saddam Plot - No - 490, Soniya Gandhi Nagar Sri Krishna Nagar, Suraram Hyderabad-Telangana 500055 Mobile: +91-7330764724Document2 pagesSK Saddam Plot - No - 490, Soniya Gandhi Nagar Sri Krishna Nagar, Suraram Hyderabad-Telangana 500055 Mobile: +91-7330764724Vilen RaiNo ratings yet

- Pass Rules: Types ApplicabilityDocument16 pagesPass Rules: Types ApplicabilityVikashNo ratings yet

- Independent Baptist Fellowship InternationalDocument2 pagesIndependent Baptist Fellowship Internationallamb.allan.676No ratings yet

- 12 ThinkingSkillssummaryDocument1 page12 ThinkingSkillssummaryroy_mustang1100% (1)

- EFL Competition Reading & English Skills TestDocument4 pagesEFL Competition Reading & English Skills TestMaja Spasovic StojanovskaNo ratings yet

- DLP Sci 7Document8 pagesDLP Sci 7Swiit HarrtNo ratings yet

- Application Guide: Study Program Human MedicineDocument4 pagesApplication Guide: Study Program Human Medicinechelcy kezetminNo ratings yet

- CV and Covering Letter Worksheet - Tourism IVDocument2 pagesCV and Covering Letter Worksheet - Tourism IVJonatan Gárate Aros HofstadterNo ratings yet

- Al Anizi2009Document11 pagesAl Anizi2009Yuzar StuffNo ratings yet