Professional Documents

Culture Documents

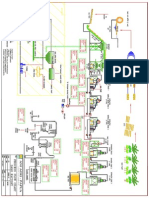

Risk Assestment Gas Terminal N Pipeline

Uploaded by

Aris Kancil0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

85 views14 pagesRisk Assestment for design of Gas Terminal & Gas Pipeline

Original Title

Risk Assestment Gas Terminal n Pipeline

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentRisk Assestment for design of Gas Terminal & Gas Pipeline

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

85 views14 pagesRisk Assestment Gas Terminal N Pipeline

Uploaded by

Aris KancilRisk Assestment for design of Gas Terminal & Gas Pipeline

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLEMENTATION OF RISK ASSESSMENT

METHODS FOR ONSHORE NATURAL GAS TERMINALS,

STORAGE SITES AND PIPELINES

1. INTRODUCTION

The onshore gas industry worldwide has a good safety record, and accidents are rare.

Nevertheless, the possibility of accidental releases can never be discounted, and it is important

that operators have an understanding of the causes and potential consequences of such releases

in order to help manage the risks involved. The development of techniques to allow quantified

risk assessments of natural gas pipelines and associated facilities to be undertaken has

accelerated in recent years, supported by mathematical modelling and experimental validation.

These techniques offer operators the opportunity to optimise safety by targeting areas where risk

can be reduced most cost-effectively, and to optimise the use of assets by avoiding inappropriate

restrictions on operations. Risk assessment techniques have been developed by Advantica for a

broad range of gas industry applications, including offshore platforms, reception terminals, high

and low pressure pipelines, compressors, gas storage and LNG sites. This paper describes the

background to the development of these techniques, the framework that has been established in

Great Britain for decision-making based partly on results of quantified risk analysis (QRA) and

techniques developed and applied by Advantica for transmission and distribution pipelines,

terminals and storage sites.

2. BACKGROUND

All activities involve an element of risk, defined as the frequency of the occurrence of an

undesired event. However carefully a system is designed, constructed and operated there

remains the possibility, however small, of failure and the consequences of such failures may pose

a risk to people or the environment. Such failures occasionally occur on gas pipelines and

installations, and it is essential to understand the risks involved, and if possible to quantify them,

to support operational decisions, for example by reducing risk in the most cost-effective way or to

support pipeline uprating, and to develop appropriate standards and design codes.

The objective of developing risk assessment techniques, and a framework for risk-based

decisions, is to enable informed and consistent decisions involving risk to be taken, and to

provide the means of maintaining levels of risk that are as low as reasonably practicable. The

use of such techniques allows operators to avoid unnecessary safety expenditure, and to

demonstrate to safety regulators, the public, and investors, that the risk presented by their

operations is managed effectively.

The use of these techniques is now well-established in Great Britain, where the pipeline

operator, Transco and its forerunners (including the former British Gas), has over 30 years

experience of transmission pipeline operations, and experience of distribution pipeline operations

stretching back over 100 years. The British system is extensive, given the relatively small size of

the country, with approximately 20,000km of transmission pipeline and 250,000km of distribution

M.R. Acton, T.R. Baldwin and R.P. Cleaver

Advantica, England

pipelines. Great Britain is a crowded island, and as a result, gas pipelines and installations are

inevitably often in close proximity to populated areas. As risk assessment techniques have

become better established design codes and legislation have developed to reflect this. For

example, Edition 4 of the IGE/TD/1 design code (Ref. 1), and recent changes in legislation in the

US, allow greater flexibility in pipeline design and operation, where demonstrated as safe by the

use of risk assessment techniques.

3. RISK ASSESSMENT

Risk can be expressed either as individual risk, meaning the frequency of an individual at

a specified location being a casualty; or societal risk, defined as the relationship between the

frequency of an incident and the number of casualties that may result. This is usually expressed

in the form of a graph of the cumulative frequency (F) of N or more casualties plotted against N

(an "FN curve"). An expectation value (i.e. the numbers of casualties expected on average per

year) may be calculated by integration of an FN curve.

To quantify the level of risk, the range of credible failure causes must be considered, and

the failure frequency for each event and the resulting consequences in terms of harm to people

need to be evaluated. The risk associated with each event is calculated by combining the results

of the failure frequency and consequence calculations, and the results for all events summed to

obtain the overall risk level for the pipeline or installation being considered. For pipelines (unlike

installations) it is important that the length of pipeline being assessed is consistent with the length

of pipeline to which the risk criterion applies, since the frequency of failure, and hence the level of

risk, increases directly with pipeline length.

In order to demonstrate that a certain level of risk is acceptable, both individual and

societal risks need to be quantified for comparison with established risk criteria. In Great Britain,

the safety regulator the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) have published individual risk criteria,

with some indication of the levels of societal risk that would be considered acceptable (Ref. 2).

However, the key test is generally to demonstrate that the calculated level of risk is ALARP (As

Low As Reasonably Practicable). This is achieved by consideration of available practical options

for reducing risk. According to HSE, in order for the level of risk to be ALARP, the cost of such

risk reduction measures must be shown to be disproportionate to the benefit in terms of risk

reduction.

The HSE uses a three-band approach in regulating industrial risks. At the top end of the

scale there are risks that are so great that they are refused altogether. At the bottom end are

situations where the risk is, or has been made, so small that no further precaution is necessary -

a broadly acceptable region. In between these two extremes is a region where risks are

tolerable only if their level has been reduced to one which is ALARP. For activities in the

tolerable region there is an expectation that society desires the benefit of the activity creating the

risk and that the nature and level of the risks are assessed and controlled using the best available

scientific techniques. Control measures should be introduced to move the residual risk towards

the broadly acceptable region until further risk reduction is impractical or the benefit gained in

risk reduction is grossly disproportionate to the cost incurred. At this point the risk is ALARP.

The risk framework outlined applies both to individual and societal risks. For individual

risks, the HSE quotes risks of fatality that are regarded as broadly acceptable (1x10

-6

per year)

and represent the boundary between tolerable and unacceptable (1x10

-3

per year for workers and

1x10

-4

per year for members of the public). These benchmark values for individual risk are based

on the fact that a level of 1 x10

-6

per year is a very low level of risk when compared to the

background level of risk for all hazards. For societal risks there are no such detailed criteria,

although guidance with respect to gas transmission pipelines is provided in the latest edition

(Edition 4) of the IGE/TD/1 design code, which includes an example of an FN type criterion for

societal risk (Figure 1). For transmission pipelines and other major hazard installations, which

have the potential to cause multiple fatality events, the consideration of societal risk is usually at

least as important as individual risk, which is often well below the broadly acceptable level.

1 10 100 1000

Number of Casualties, N

1.00E-10

1.00E-9

1.00E-8

1.00E-7

1.00E-6

1.00E-5

1.00E-4

F

r

e

q

u

e

n

c

y

o

f

N

o

r

M

o

r

e

C

a

s

u

a

l

t

i

e

s

p

e

r

Y

e

a

r

Tolerable risk based upon

ALARP considerations

Negligible or

acceptable Risk

Figure 1: Sample FN criterion (from IGE/TD/1 Edition 4 Ref. 1)

Advantica has developed quantified risk assessment methodologies that allow individual

and societal risks to be calculated across the full range of gas industry installations and plant.

Some of these applications are described in the following sections.

4. TRANSMISSION PIPELINES

4.1 Methodology

In Great Britain, gas transmission pipelines are generally laid in accordance with the

IGE/TD/1 design code prepared by the Institution of Gas Engineers and Managers (Ref. 1). This

has historically been a prescriptive code, however the most recent editions allow for flexibility

where justified by a risk assessment. Such a need arises, for example, in the event of an

infringement to the code in the vicinity of an existing pipeline, or if the operator wishes to change

the operation of the pipeline in a way not foreseen at the time the pipeline was laid, for example

by increasing the operating pressure ("uprating"). To address these issues, Transco (formerly

British Gas) developed a risk assessment package for transmission pipelines. The package had

limited functionality, and was tailored specifically to British requirements. In 1994, an

international collaboration of a number of gas transmission companies was formed to develop a

more sophisticated tool called PIPESAFE, which could be applied to a wider range of situations,

and with improved functionality. PIPESAFE is a software package for PCs that contains a range

of mathematical models, linked in a logical manner, to calculate individual and societal risk. It is

based on many years of research into the causes and consequences of transmission pipeline

failures, including both mathematical modelling and experimental validation at both small and

large scale.

Phase 1 of the collaboration funded the development of the new PIPESAFE package by

Advantica (Ref. 3). This included new models, for a wide range of failure causes, and new

consequence models including a model to predict the initial transient stages of a fire following

immediate ignition of a pipeline rupture. The collaboration also developed a pipeline damage

database, which allowed members of the collaboration to pool damage data for pipelines to

enable failure frequency models to be modified to make appropriate predictions based on

operational experience in different countries or companies.

In Phase 2, a detailed analysis of the sensitivity of PIPESAFE predictions to the input

parameters and of the levels of uncertainty associated with the model predictions was carried out,

and the predictions of PIPESAFE were compared with information available from incidents.

Phase 2 also included a comparison of the risk calculation methods used in the different

companies participating in the project, and considered ways of extending the risk calculation

methods in PIPESAFE to give greater flexibility.

In Phase 3, PIPESAFE has been refined so that a wider range of failure modes can be

considered, and provides greater flexibility by implementing a number of the risk calculation

methods identified in Phase 2, thus allowing the package to meet the different requirements of

gas companies operating in different countries (Ref. 4).

The main elements of a pipeline failure considered in the PIPESAFE methodology are

failure cause, failure frequency, failure mode, gas outflow, dispersion, ignition, thermal radiation

and thermal effects. Knowledge and models are combined in a logical manner, to calculate

casualty probability and risk. These elements are described in more detail below:

Failure - Failure of a gas pipeline can occur due to a number of different causes such as

external interference, corrosion, fatigue, ground movement, material or construction defects. The

failure modes that can occur are leaks (punctures), or breaks (ruptures). The failure mode is

determined by the length, depth and type of defect, and is dependent on the pipe diameter, wall

thickness, material properties and the operating pressure. Estimates of failure probability can

either be made from historical data where appropriate, or by the application of predictive methods.

Recently, Advantica has also been at the forefront of developing new predictive methods,

sometimes known as Structural Reliability Assessment (SRA), to quantify the significance of the

effect on overall failure probability of changes in pipeline parameters (Ref. 5).

Preventive measures to reduce the likelihood of failure offer the main opportunity to

reduce risk, and it is these measures that generally form the basis of an ALARP calculation.

Gas Outflow - Due to the pressure at which transmission pipelines are operated, a failure

of a pipeline leads to a turbulent and complex gas release. Following a rupture, or large puncture,

there will be rapid depressurisation in the vicinity of the failure. For buried pipelines, the overlying

soil will be ejected with the formation of a crater of a size and shape which influences the

behaviour of the released gas. Depending on the alignment of the pipe ends in the case of a

rupture, the gas will escape to the atmosphere in the form of a jet, or jets. At the start of the

release, a highly turbulent mushroom shaped cap is formed which increases in height above the

release point due to the source momentum and buoyancy, and is fed by the gas jet and entrained

air from the plume which follows. In addition to entrained air the release can also result in

entrainment of ejected soil into the cap and plume. Eventually, the cap will disperse due to

progressive entrainment and a quasi-steady plume will remain. Immediately following a rupture

the flow from each side of the rupture will be balanced. However, at later stages the flow through

each limb will be determined by the behaviour of the pipeline system. This is affected by features

such as compressor stations or feeds from, or to, other pipelines which may be at large distances

from the failure point. These boundary conditions determine whether the flow through the

pipeline at the rupture will decrease to zero or to a steady-state flow.

Ignition - Ignition can occur at any time during the release. If it occurs immediately on, or

shortly after, rupture, a transient fireball will occur. The fireball, which is the result of combustion

of the mushroom-shaped cap lasts, typically, for up to thirty seconds, and then burns out leaving

a quasi-steady state fire. If ignition occurs after the initial highly transient phase, the transient

involved in establishing a quasi-steady fire is much less pronounced and, for modelling purpose,

the consequences of the quasi-steady fire only are considered.

Mathematical models to predict the dispersion behaviour of an unignited plume of gas

released by a high pressure pipeline failure can be used for specific situations to evaluate the

likelihood of flammable gas concentrations being produced at a specific location where ignition

sources are available. Generally, however, routine assessments take values for ignition

probability based on historical data (Ref. 6).

Thermal Radiation - The levels of thermal radiation incident on the area surrounding the

ignited release vary with time after rupture and with distance from the release point, and are

dependent on the shape, nature and extent of the fire (determined by the source and atmospheric

conditions), and the atmospheric transmissivity between the fire and the receiver (determined by

the humidity). Following the initial fireball phase after a pipeline rupture, the gas outflow gradually

decays, and the fire behaviour can be treated as though it is quasi steady-state.

Thermal Radiation Effects - Both people and property in the vicinity of an ignited pipeline

release can be affected by the levels of incident thermal radiation. People can become casualties

as a result of receiving large doses of thermal radiation, and buildings can be ignited by thermal

radiation directly from the fire or from secondary fires (e.g. from burning vegetation). A number of

different criteria can be used for predicting casualties, depending on the definition of a casualty

being used, taking account of the distance from the pipeline and the availability of shelter.

Risk Calculations - The calculation of risk at a particular location from an extended

pipeline source is complicated by the fact that the failure position is unknown in advance. It is

necessary to consider the effects from the predicted pipeline fire along the interaction length,

which is the length of pipeline that could pose a hazard to the development or point of interest.

Individual risk is calculated at specified locations and distances from the pipeline, and societal

risk can either be calculated generically, based on estimates of population density, or in a site-

specific manner, taking account of the precise locations of buildings and people.

4.2 Validation

In order to have confidence in the predictions of a package such as PIPESAFE, it is

essential to demonstrate that the results are realistic. The approach adopted for the

consequence models in PIPESAFE has generally been to develop the models on the basis of

theoretical understanding, guided by the results from small scale experiments. However,

because many of the processes involved are strongly dependent on the scale of the event,

especially fires, it is also necessary to conduct experiments at as large a scale as practical, to

validate the models and to provide an essential input to further development. All of the

consequence models in PIPESAFE have been validated by comparison with results from

comprehensive programmes of experiments carried out at very large scale, mainly conducted at

the Advantica Spadeadam Test Site (see Figure 2), in the north of England. Spadeadam is a

unique facility, consisting of a large area of open ground within an area controlled by the Ministry

of Defence, equipped with gas storage and delivery systems and the necessary infrastructure to

allow large and full scale experiments to study the behaviour of accidental releases of gas and

other fuels at high and low pressure, to be conducted safely.

Figure 2. Aerial view of Advantica Spadeadam Test Site, where many of the experiments

were performed to provide data for model development or validation

In addition to experiments undertaken at Spadeadam, a very important source of data for

validation of the models and methodology in PIPESAFE is the results of two full scale

experiments conducted in Canada as a collaborative project, managed by Advantica (Ref. 7).

The experiments involved the deliberate rupture of a 76km length of 914mm diameter natural gas

pipeline operating at a pressure of 60 bar, with the released gas ignited immediately following the

failure. Over 200 instruments were successfully deployed in each experiment to take detailed

measurements, which included the weather conditions, the gas outflow, the size and shape of the

resulting fire, and the thermal radiation levels. Large fires were produced in both experiments,

with maximum flame heights of over 500m in the initial stages, which decayed rapidly in size as

the gas outflow reduced following the initial rupture.

As a further check, the predictions of PIPESAFE have also been compared against

information collected from actual pipeline incidents, involving rupture and ignition of the gas

released. Three types of comparisons between PIPESAFE predictions and incidents were made:

Building ignition times,

Burn areas surrounding the failure, and

Injuries to people.

If the ignition time of any buildings adjacent to the pipeline fire is known this can be

compared directly with results from PIPESAFE. PIPESAFE can generate ignition times for

structures based on either piloted or spontaneous ignition of wood.

Information relating to the burnt area around the pipeline fire is generally available from

pipeline incident reports. However, comparisons with modelling predictions can be complicated

by a number of factors, for example, the subjective nature of determining the burnt area.

Materials that have been scorched may appear to be similar to materials that have actually

ignited and been partially burnt, but the levels of radiation required for these two scenarios could

be substantially different.

In addition to uncertainties in quantifying the consequences of an incident, there may also

be difficulties in making direct comparisons, because the information available from incident

reports is often not sufficient to provide all of the necessary inputs to PIPESAFE. For example, it

may be that the features of the pipeline system governing the boundary conditions following

failure (as required by the outflow model) are not well defined. This means that incident data are

not suitable for detailed model validation. They can, however, be used to give an indication of a

general level of consistency of the predictions from PIPESAFE.

An exercise to compare the predictions of PIPESAFE with details of 18 incidents and the

two full-scale experiments indicated that PIPESAFE gives a reasonable but generally

conservative prediction of burn area. However, because of the subjective nature of determining

the burnt area, and uncertainty due to fire spread and moisture content of the surrounding

combustible materials, a wide spread in the predicted and reported burn areas was found.

A more rigorous test of the PIPESAFE consequence models was possible where ignition

times and thermal radiation effects on people were reported. Where comparisons were possible,

the PIPESAFE predictions gave good agreement with the ignition time of adjacent properties.

The level of burn injuries seen in the population near to the pipeline fire was also consistent with

the predictions of PIPESAFE. The PIPESAFE package has also been subjected to a

comprehensive programme of software testing, and independent checking.

4.3 Applications

Risk assessment may be applied to transmission pipelines for a variety of reasons,

including:

Infringements to pipeline design codes

Pipeline uprating

Pipeline design and routing

Land use planning

Emergency planning

The most frequent use of PIPESAFE is to make decisions on the appropriate course of

action when developments encroach upon the pipeline. When pipelines are laid in Great Britain,

they are routed to IGE/TD/1 such that no buildings would be located within 1 BPD (Building

Proximity Distance) of the pipeline. Encroachments can cause code infringements of two main

types:

a) Proximity infringements

b) Population density infringements

Encroachments to the pipeline are identified when the pipeline is surveyed according to

the methods and frequencies recommended in the IGE/TD/1 code. The survey will identify if any

buildings have been built within 1 BPD of the pipeline or if the population density has increased

within the survey zone, defined as 4 BPD either side of the pipeline, due to further development

between 1 and 4 BPD from the pipeline, such that the population density now exceeds that for the

pipeline designation. This can occur, for example, when the population density surrounding a

pipeline increases sufficiently to be classed as suburban, although the pipeline itself is

designated as being laid and run to standards appropriate for a rural area.

A pipeline risk assessment may be carried out to determine the risk levels at any

infringement and the results used to decide on the appropriate course of action. Having

calculated the risk levels at the infringement, the key determining factor is usually the level of

societal risk. This is because the high design integrity of most pipelines means that individual risk

levels are rarely a problem, although there is still the potential for high numbers of casualties.

The determining factor as to whether a risk is acceptable or unacceptable, is whether the risk

from the pipeline is ALARP (As Low As Reasonably Practicable). This will be assessed by

evaluating the risk reduction arising from a number of possible measures, and carrying out cost

benefit calculations on each option before a decision is made.

Another major application of the use of pipeline risk assessment techniques is pipeline

uprating, where the pipeline operator needs to increase capacity, usually because of a forecast or

actual rise in demand, without the high cost associated with construction of an additional pipeline.

In this situation, the key determining factor is the effect of the increased pressure on the integrity

of the pipeline, and Structural Reliability Assessment (SRA) techniques are applied to determine

whether or not the predicted failure frequency will be significantly increased by the proposed

change in operating pressure. The predicted change in failure frequency is then used to assess

the increase in risk to the population in the vicinity of the pipeline, in order to determine the

acceptability or otherwise of the risk levels.

The SRA approach has been applied in examining the potential for pipelines with a design

factor of up to 0.72 (the current limit in IGE/TD/1) to operate at a higher design factor (up to 0.8).

This approach, which is recognised in the latest edition of IGE/TD/1 (Ref. 1), involves:

Identification of all credible failure mechanisms, based on consideration of all the

loads the pipeline is likely to see and the ability of the pipeline to resist those loads

Assessment of the proportionate increase in failure probability when operating at the

Higher Design Factor rather than 0.72, for each failure mechanism

Assessment of whether the absolute value of failure probability from a particular

failure mechanism at the Higher Design Factor is a significant contributor to the

overall pipeline failure probability. This applies for each failure mechanism for which

the proportionate increase in failure probability is significant.

These techniques have been successfully used to demonstrate the potential for pipeline

uprating in order to meet forecast growth in demand for gas in Great Britain as an alternative to

new pipeline construction.

5. DISTRIBUTION PIPELINES

5.1 Methodology

Although the gas distribution industry has a good safety record, a small number of

incidents involving failures of distribution pipes occur each year, and an understanding of the

hazards and risks associated with distribution pipeline operations is important in order to manage

the risks effectively. To quantify the risk posed by distribution pipes the causes of failure and the

failure modes of the pipe together with the possible consequences of the failure need to be

established. The main hazards posed by releases of natural gas are from an explosion or a fire.

Explosions may occur following in-ground failures of distribution pipelines, which for low

pressure pipelines (typically < 2 bar) usually result in gas being released into the ground around

the failure. The presence of soil around the failure normally reduces the amount of gas released

compared to a release directly to atmosphere. The gas is released into the soil and will travel in

the direction of least resistance to flow. When the surface above the failure is open (e.g. grass)

the gas is likely to vent through the upper surface. However, when the surface above the failure

is sealed (e.g. by a tarmac or concrete covering) the gas may travel large distances in the soil.

This is especially likely to happen if there are tracking routes in the ground along which the gas

can travel easily. Examples of these are disused drainage pipes, a sandy or gravel pipe bed or

the routes of other pipes. In some cases gas can reach and enter an adjacent property in

sufficient quantities to form a flammable gas/air mixture, which could be ignited by ignition

sources such as domestic appliances.

Fires following gas releases directly to atmosphere can occur as a result of interference

damage to the pipe by excavation work or as a result of an in-ground failure of a higher pressure

pipeline (typically greater than 2 bar) which removes the ground cover above the pipe. This can

lead to releases of significant quantities of gas. In such situations, the historical record suggests

that relatively few releases are ignited. However, the sources of ignition for those that are ignited

are very varied, including adjacent damaged electricity cables, vehicles or equipment in the

vicinity. In the event of ignition, the size of the fire is affected by parameters including the

pressure of the pipeline, the size of the failure, the release geometry and the weather conditions.

Figure 3 shows an experiment performed at Spadeadam to study an ignited release from a

distribution main into a trench.

Figure 3. Example of experimental simulation of a fire produced following a release from a

distribution main.

Advantica has developed two risk assessment methodologies to quantify the risk

associated with the explosion and fire hazards (Ref. 8).

5.2 Explosion Methodology

The risk assessment methodology developed to predict the frequency of an explosion

occurring for distribution pipelines uses a combination of predictive mathematical models and

historical statistics on pipeline failures. The risk assessment methodology predicts the likelihood

and consequences of an explosion incident occurring per km of distribution pipeline per year. It

uses a site-specific approach to calculate the risks and therefore a survey of the area surrounding

the pipeline needs to be conducted before the pipeline can be assessed. The methodology

considers the likelihood of each of the different stages occurring in turn.

The first step is to calculate the likelihood of an in-ground failure of the pipe, using

historical data on failures of pipes. The model calculates the quantity of gas released from the

pipe, requiring the range of possible failure sizes, established from historical data, and the

pipeline pressure to be known.

The behaviour of the gas as it travels through the ground is calculated using

mathematical models. Three mathematical models have been developed by Advantica and

validated against full scale experiments at the Spadeadam test site. One is used in cases where

the surface above the pipe is sealed (e.g. by tarmac or concrete) and this assumes the gas

spreads radially away from the failure but cannot vent through the sealed upper surface. Another

is used where the surface is open (e.g. grass) where the gas can vent through the upper surface.

The final model is for situations where there is a tracking route in the ground along which gas will

travel preferentially.

The next stage is to calculate the likelihood and quantity of gas that could enter any

adjacent properties. The probabilities of gas entering properties given the failure of an adjacent

buried distribution pipeline are calculated using historical data on the failures of pipelines. Given

that gas enters the property the quantity of gas entering is calculated using mathematical models.

Following gas ingress, the build-up of gas within the property is calculated, for a range of

likely room sizes, ventilation rates and gas entry points. The build-up of gas within the room is

calculated assuming perfect mixing of the gas and air from the point of entry of the gas to the top

of the room. The calculations for the build-up of gas within the property are also combined with

calculations to assess the likelihood and consequences of the release of gas being detected and

action taken subsequently to disperse the gas release, such as opening windows and doors to

increase the ventilation rate.

The final stage is to assess the likelihood of any flammable gas/air mixtures being ignited

and the consequences of any explosions. Ignition probability is estimated from experience of

dealing with gas escapes and explosion incidents. Advanticas model to calculate the

consequences of confined explosions has been developed and validated against full scale

explosion experiments.

5.3 Fire Methodology

The approach adopted to assess risks associated with releases to atmosphere from

damaged distribution pipelines, and the resulting fire if ignition occurs, closely follows the

methodology for gas transmission pipelines described previously. The approach addresses all

the main elements required to undertake a quantified risk assessment of the fire hazard, namely

failure cause and frequency, failure mode, gas outflow, ignition, thermal radiation and thermal

radiation effects. Knowledge and mathematical models are combined in a logical manner to

calculate risk, in an integrated software package similar to PIPESAFE.

For PE pipelines, the main cause of failure is third party interference damage. Historical

data from Great Britain is used to estimate the likelihood of an impact on a PE pipeline, and the

likely damage that could be produced. Generally, interference damage leads to a release of gas

directly to atmosphere, although it is possible for activities such as moling techniques for laying

cables, for example, to lead to an in-ground failure. In such cases, a release directly to

atmosphere may still occur, with the potential to present a significant fire hazard, because gas

released from failures of pipelines operating at pressures in the region of 2 bar and above will

generally lead to the removal of the ground cover above the pipeline. Larger PE pipelines,

particularly those constructed from materials such as High Density Polyethylene (HDPE), offer

significant resistance to impact damage, and only a proportion of impacts will be of sufficient force

to cause rupture.

5.4 Applications

In Great Britain both metallic and PE pipes are used to transport natural gas within the

distribution system at pressures of less than 7 bar. If not addressed, ageing distribution pipelines

constructed from iron can fail, possibly leading to an explosion hazard as described in this paper.

In order to minimize the likelihood of such events, a programme has been undertaken to replace

selected cast or ductile iron pipelines with new PE pipelines. Since the commencement of the

replacement programme in Great Britain, the number of incidents associated with failures of

distribution pipelines has been significantly reduced.

One application of the risk assessment methodologies is in identifying metallic distribution

pipelines for replacement. The process by which pipelines are selected for replacement has

recently become more formalised with the introduction of risk-based techniques. The

methodology for assessing explosion risk described in this paper has been implemented to

optimise the effectiveness of the replacement programme, by selecting pipes for replacement on

the basis of risk.

The risk assessment methodologies can also be used to help develop industry standards

and are being used to support design guidelines for the installation of new PE pipelines. The

models can be used to determine hazard-based proximity distances for new pipeline projects or

to assess the impact on the risk of changes in the way distribution systems are operated, such as

the effect on risk of increasing or reducing the operating pressures of distribution pipelines.

6. TERMINALS AND STORAGE SITES

Under British legislation, all industrial sites that store above a certain quantity of a

flammable or toxic substance, are required to produce and maintain a 'Safety Report'. The report

has to be submitted at regular intervals to the HSE and the relevant Environment Agency, who

ensure that health, safety and environmental issues are being addressed in a responsible manner.

The Safety Reports should describe measures to prevent accidents and limit their consequences

and provide a systematic analysis that determines the safety measures on the site. Unlike the

previous Regulations, the emphasis in the reports is now on demonstration. Therefore, sufficient

details are required to enable the inspectors to understand the purpose of the establishment and

the nature of the surrounding environment and to verify that appropriate management

arrangements, including the safety management system, are in place. Information should be

provided on the possible releases that could occur, identifying and analysing in detail those

incidents that might give rise to major accidents to people or the environment.

By their very nature, major accidents at terminals or storage sites have a low frequency,

albeit with potentially high consequences. Assigning quantitative measures to the risks of such

accidents is difficult, as there are few observations on which to base a judgement of how the

scenarios may evolve. In such cases, the consequences are often sensitive to the assumptions

that have to be made in representing the scenario within the analysis. Using a worst-case

analysis or considering only a single, representative case may distort the assessment compared

with a full evaluation, taking into account the range of ways in which an accident may develop.

This is similar to the situation that has arisen in evaluating the explosion risks on offshore

platforms, particularly those situated in the North Sea. Here a worst-case analysis, involving

ignition of a uniform stoichiometric mixture throughout a module, may lead to very severe blast

loading criteria being adopted in the design process. The results of a recent joint industry project,

carried out by Advantica, Shell Global Solutions and Gexcon, has demonstrated that releases are

likely to lead to a range of flammable cloud sizes and hence, if these are ignited, overpressures

(Ref. 9). Studies by Advantica have shown that taking into account the likely range of explosion

pressures, through the construction of overpressure excedance curves, for example, allows more

realistic design criteria to be adopted (Ref. 10).

Just as for the offshore assessments, Advantica has developed a similar risk assessment

methodology for onshore plant. This allows the different realisations of scenarios to be analysed,

taking into account relevant parameters such as release and wind directions. Details of this

method have been summarised in recent papers (Refs. 11 and 12). The methods allow the

location specific risk to individuals, either on or off the site, to be evaluated. Further, by

accounting for the residency of different groups of people in different locations, the risk to average

and the most exposed groups of people can be evaluated. This is useful in that the values can

be compared with the published acceptability criteria (Ref. 2), as noted previously. The method

also allows an assessment of the risk to workers in occupied buildings to be evaluated, in

accordance with methodology incorporated within the Guidelines issued by the Chemical

Industries Association (Ref 13) and in associated publications (Ref. 14).

The societal impact of the major accidents can also be addressed as a result of these

calculations. Curves showing the frequency F with which N or more casualties are predicted to

occur can be constructed from the frequency and number of casualties for each individual

realisation. Such curves can then be compared with acceptability criteria for societal impact, as

for transmission pipelines, although as noted earlier at present there is rather less guidance

published as to the exact location of the bounding curves for individual installations.

Nevertheless, the method allows the contributions from the different realisations to be analysed.

The cases that contribute the most to the risk can be identified and, hence, guidance can be

given on those situations for which risk reduction should be considered. The FN curve can also

be analysed to determine the expectation value of the number of casualties any scenario could

produce. When this value is multiplied by the event frequency, a single measure of the risk is

obtained. In an offshore context, this is sometimes referred to as the expected loss of life for a

given accident scenario. This number can be used to rank the different scenarios and provides a

useful way of comparing a low frequency - high consequence scenario with a more likely, but less

severe scenario. This approach has been adopted by Advantica in a number of Safety Reports.

It is noted that using this method may reveal that some preconceived ideas about what is

the worst case are not always correct. Figure 4 shows one specific example of this type of

analysis, in which a measure of the maximum harm from a specific release of liquefied natural

gas (LNG) is plotted against the time of ignition.

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

0 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 8000 9000

Ignition Delay (s)

R

e

s

u

l

t

i

n

g

M

a

x

i

m

u

m

H

a

r

m

Figure 4. Example of analysis comparing maximum harm arising for different ignition

delay times following a large gas release

It would have been difficult to have guessed before hand what would have been the

sensitivity to the time of ignition for this situation, as shown in Figure 4.

As well as being of use when carrying out qualitative risk assessments for Safety Reports

for example, these methods are of great help in cost benefit analysis. As noted in (Ref. 11), using

worst-case assumptions can often mask the benefits of protective measures, as they may have

little effect on the worst-case realisation. However, using the methodology allows a correct

identification of suitable measures to be taken to reduce risks, as the impact of the measure on all

the different realisations is assessed. Again, the HSE have given guidance as to how such cost

benefit analyses should be performed as a part of an ALARP demonstration, if required, for a

specific site.

7. DISCUSSION

The above sections have demonstrated how methodology has been developed to enable

assessments to be made of the risks posed by onshore gas installations and transmission and

distribution pipelines. This methodology can be used to assess the impact of changes at the

design stage and to optimise expenditure to achieve the maximum benefit in terms of risk

reduction. The methodology can be used within the context of a wider cost benefit analysis to

support arguments that demonstrate to a wider audience that risks have been reduced to as low

as is reasonably practicable the so-called ALARP criteria for risk reduction adopted within Great

Britain by the HSE. However, the basic approach of developing a linked series of consequence

and frequency models that can address the many different possible realisations of a single

accident scenario is equally applicable to other applications within the onshore gas supply system.

For example, Advantica has produced packages to assess the risks arising from gas services,

connecting the distribution mains to individual domestic, industrial or commercial properties. The

packages have been extended to consider both metallic and PE pipes, combining knowledge of

incident history to determine appropriate failure frequencies with consequence models for fires or

gas movement and explosion. An important aspect of these models is modelling the response of

people to gas detection and the possibility of successful intervention to prevent fires or explosions.

Work such as this allows the most safety critical areas on the whole of the gas supply chain to be

identified and, hence, expenditure to be targeted to achieve cost effective risk management.

8. REFERENCES

1. "Steel Pipelines for High Pressure Gas Transmission", IGE Code TD/1 Edition 4,

Communication 1670 (2001).

2. Reducing Risks, Protecting People, 2001, HSE Books.

3. Acton, M.R., Baldwin, P.J., Baldwin, T.R., and Jager, E.E.R. The Development of the

PIPESAFE Risk Assessment Package for Gas Transmission Pipelines, ASME International,

Proceedings of the International Pipeline Conference 1998 (IPC98), Calgary, June 7-11 1998.

4. Acton, M.R., Baldwin, T.R., and Jager, E.E.R. Recent Developments in the Design and

Application of the PIPESAFE Risk Assessment Package for Gas Transmission Pipelines,

ASME International, Proceedings of the International Pipeline Conference 2002 (IPC02),

Calgary, 29

th

Sept. 3

rd

Oct. 2002.

5. Francis, A. and Senior, G. The Use of Reliability Based Limit State Design Methods in

Uprating High Pressure Gas Pipelines ASME International, Proceedings of the International

Pipeline Conference 1998 (IPC98), Calgary, June 7-11 1998

6. Bolt, R. and Owen, R.W. "Recent Trends in Gas Pipeline Incidents (1970 1997). A Report

by the European Gas Pipeline Incident Data Group (EGIG), IMechE Conference on Ageing

Pipelines, Newcastle, October 1999

7. Acton, M.R., Hankinson, G., Ashworth, B.P., Sanai, M., and Colton, J.D. "A Full Scale

Experimental Study of Fires following the Rupture of Natural Gas Transmission Pipelines",

ASME International, Proceedings of the International Pipeline Conference 2000, Calgary,

October 1-5 2000

8. Acton, M.R. and Smith, B.J., The Development and Application of Risk Assessment

Techniques for Gas Distribution Pipelines, Rio Oil & Gas Conference, IBP2000.

9. OTC Paper 14134, Investigation of Gas Dispersion and Explosions in Offshore Modules; D.M.

Johnson, R.P. Cleaver, J.S. Puttock, C.J.M. Van Wingerden, Houston, May 2002.

10. Assessing Gas Accumulation and Explosion Potential on Offshore Modules, R. P. Cleaver

and D. M. Johnson, IGRC, Amsterdam, November 2001.

11. Cleaver RP, Robinson CG and Halford AR. Analysing High Consequence, Low Frequency

Accidents on Process and Storage Plants, Chemical Engineer, July 2002.

12. Modelling High Consequence, Low Probability Scenarios, R.P. Cleaver, A.R. Halford and

C.E. Humphreys to be published in Hazards XVII, Manchester, April 2003.

13. Guidance for the location and design of occupied buildings on chemical manufacturing sites,

Chemical Industries Association (CIA) publication, February 1998.

14. Location and design of occupied buildings assessment step by step, M. Goose, IChemE

Symposium Series No 147, 1999.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Energi Indonesia 2012Document29 pagesEnergi Indonesia 2012Aris KancilNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Claude Frederic BastiatDocument3 pagesClaude Frederic Bastiatapi-26172897No ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- SAGU EXTRACTION FLOW DIAGRAMDocument3 pagesSAGU EXTRACTION FLOW DIAGRAMAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Flow Sheet Sago Rev Feb 2014 Flow ChartDocument1 pageFlow Sheet Sago Rev Feb 2014 Flow ChartAris KancilNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Segmen Mjpahit Jatingaleh MjpahitDocument1 pageSegmen Mjpahit Jatingaleh MjpahitAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- SImulasi Mass Balance - 18april2013 - As (Version 1)Document7 pagesSImulasi Mass Balance - 18april2013 - As (Version 1)Aris KancilNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- PipeP PE2406 CharacteristicDocument3 pagesPipeP PE2406 CharacteristicAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Segmen Jatingaleh Bawen-3of3Document1 pageSegmen Jatingaleh Bawen-3of3Aris KancilNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- 01 DS Ball Valve CSDocument4 pages01 DS Ball Valve CSAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Power distribution concept for 3000 KVA steam turbine generator panelDocument1 pagePower distribution concept for 3000 KVA steam turbine generator panelAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Water Flow Diagram Ver Feb 27022013Document1 pageWater Flow Diagram Ver Feb 27022013Aris KancilNo ratings yet

- Blok Diagram Ekstrasi Sagu Rev 1 April 2013Document4 pagesBlok Diagram Ekstrasi Sagu Rev 1 April 2013Aris KancilNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Cng-000-El-011 Voltage Drop Calculation (MS) r1Document6 pagesCng-000-El-011 Voltage Drop Calculation (MS) r1Aris KancilNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Flow Sheet Layout3Document1 pageFlow Sheet Layout3Aris KancilNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Burlian Plot Plan Burlian - Okt 2012 2007 ModelDocument1 pageBurlian Plot Plan Burlian - Okt 2012 2007 ModelAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Gas Line Sizing - SPBG PalembangDocument24 pagesGas Line Sizing - SPBG PalembangAris KancilNo ratings yet

- 10.Cnb-dwg-p-006 Layout SPBG Jalan Ki MeroganDocument1 page10.Cnb-dwg-p-006 Layout SPBG Jalan Ki MeroganAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Pipe wall thickness calculation sheet for high pressure natural gas lineDocument1 pagePipe wall thickness calculation sheet for high pressure natural gas lineAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Risk ManajemenDocument4 pagesRisk ManajemenAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Gas Transmision CodeDocument59 pagesGas Transmision CodeAris KancilNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Instrument and Control Design BasisDocument3 pagesInstrument and Control Design BasisAris KancilNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- 01 DS Ball Valve CSDocument4 pages01 DS Ball Valve CSAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Kalkulasi Studikasus KSDocument6 pagesKalkulasi Studikasus KSAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Spek PipaDocument7 pagesSpek PipaAris KancilNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Fire and Gas Detection SpecificationDocument4 pagesFire and Gas Detection SpecificationAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Gas Technology Institute PresentationDocument14 pagesGas Technology Institute PresentationAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Valve SheetDocument23 pagesValve SheetAris KancilNo ratings yet

- Spesifikasi Truc HyundayDocument32 pagesSpesifikasi Truc HyundayAris Kancil50% (4)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Biogas GuideDocument63 pagesBiogas GuideAris KancilNo ratings yet

- SDS SikaHyflex 250 Facade - EU - ENDocument9 pagesSDS SikaHyflex 250 Facade - EU - ENFajar Reza LaksanaNo ratings yet

- D - 2022 June Vol 19 No 1 Chemical Health Risk Assement of Cleaning Activities in An Office BuildingDocument7 pagesD - 2022 June Vol 19 No 1 Chemical Health Risk Assement of Cleaning Activities in An Office BuildingTs Mohammad Hezrie ZainolNo ratings yet

- Electrocuted HelperDocument2 pagesElectrocuted Helperjacc009No ratings yet

- Quality Assurance Control Supplier Manager in San Francisco Bay CA Resume Tony McKelveyDocument2 pagesQuality Assurance Control Supplier Manager in San Francisco Bay CA Resume Tony McKelveyTonyMcKelveyNo ratings yet

- Eng. Nouh, ASP - CSP Videos LinksDocument2 pagesEng. Nouh, ASP - CSP Videos LinksAhmed AbdulfatahNo ratings yet

- Physical security system essentialsDocument5 pagesPhysical security system essentialsLindo Gondales Jr.No ratings yet

- Acs 580Document36 pagesAcs 580Francisco ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Leonardo, Trisha Lou C. Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesLeonardo, Trisha Lou C. Lesson PlanTrish LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet Aristoflex AVC PDFDocument12 pagesSafety Data Sheet Aristoflex AVC PDFArsiaty SumuleNo ratings yet

- Director Safety Risk Management in Denver CO Resume Scott MaxeyDocument3 pagesDirector Safety Risk Management in Denver CO Resume Scott MaxeyScottMaxeyNo ratings yet

- JSA Scaffolding Erection and Dismentling New 2021Document5 pagesJSA Scaffolding Erection and Dismentling New 2021Captain ChickenNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- HSE-000-PLN-0017 Plan To Control Chemical HazardsDocument13 pagesHSE-000-PLN-0017 Plan To Control Chemical Hazardsernesto100% (1)

- European Standard EN 1838 Norme Europeenne Europaische NormDocument12 pagesEuropean Standard EN 1838 Norme Europeenne Europaische NormAts ByNo ratings yet

- MSDS - IC - Cleaner Norma PDFDocument8 pagesMSDS - IC - Cleaner Norma PDFDhea sylvia frasiscaNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet for LUBLIGHT #500-WDDocument4 pagesSafety Data Sheet for LUBLIGHT #500-WDAzuan MABKNo ratings yet

- Electrical Engineering Internship CertificateDocument6 pagesElectrical Engineering Internship Certificatexosim12242No ratings yet

- HS-176ENG Safety Bulletin No 42Document4 pagesHS-176ENG Safety Bulletin No 42saiedNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet: 901 Janesville Ave. Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-0901 Phone: 920-563-2446Document2 pagesSafety Data Sheet: 901 Janesville Ave. Fort Atkinson, WI 53538-0901 Phone: 920-563-2446FalihNo ratings yet

- Diesel generator operation JSADocument3 pagesDiesel generator operation JSASaiyad RiyazaliNo ratings yet

- Unilap 100 E: Installation TesterDocument4 pagesUnilap 100 E: Installation Testerchoban19840% (1)

- PTSBD Course Outline on OSH2Document21 pagesPTSBD Course Outline on OSH2ilhammkaNo ratings yet

- TR Automotive Electrical Assembly-NC IIDocument73 pagesTR Automotive Electrical Assembly-NC IIMichael V. Magallano100% (1)

- Human Factors Presentation on Maintenance SafetyDocument72 pagesHuman Factors Presentation on Maintenance SafetyTDH100% (1)

- Employee Daily Ppe Log SheetDocument6 pagesEmployee Daily Ppe Log SheetRaynus ArhinNo ratings yet

- Safety QuestionerDocument3 pagesSafety QuestionerPremji SanNo ratings yet

- Safety Data Sheet for Argon, CompressedDocument2 pagesSafety Data Sheet for Argon, CompressedDragan TadicNo ratings yet

- 80-140-100-15D-111-7S-00 Tech Manual REV MAY2017 PDFDocument121 pages80-140-100-15D-111-7S-00 Tech Manual REV MAY2017 PDFmarcoNo ratings yet

- Dow Corning Singapore Chemical Safety Data Sheet for 3145 RTV Adhesive/SealantDocument7 pagesDow Corning Singapore Chemical Safety Data Sheet for 3145 RTV Adhesive/Sealantwillis kristianNo ratings yet

- Iosh Noise at Work Risk Assessment CourseDocument7 pagesIosh Noise at Work Risk Assessment Coursebcqv1trr100% (2)

- Tudalen 65 - Expires 01-06-2025Document13 pagesTudalen 65 - Expires 01-06-2025Muhammad YusufNo ratings yet

- The Cyanide Canary: A True Story of InjusticeFrom EverandThe Cyanide Canary: A True Story of InjusticeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (51)

- The Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the WorldFrom EverandThe Rights of Nature: A Legal Revolution That Could Save the WorldRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Down to the Wire: Confronting Climate CollapseFrom EverandDown to the Wire: Confronting Climate CollapseRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- 3rd Grade Science: Life Sciences in Eco Systems | Textbook EditionFrom Everand3rd Grade Science: Life Sciences in Eco Systems | Textbook EditionNo ratings yet

- Art of Commenting: How to Influence Environmental Decisionmaking With Effective Comments, The, 2d EditionFrom EverandArt of Commenting: How to Influence Environmental Decisionmaking With Effective Comments, The, 2d EditionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)