Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Regional Rootedness of Places: You Can Plan With That: Lineu Castello & Iára Regina Castello

Uploaded by

qpramukantoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Regional Rootedness of Places: You Can Plan With That: Lineu Castello & Iára Regina Castello

Uploaded by

qpramukantoCopyright:

Available Formats

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

1

THE REGIONAL ROOTEDNESS OF PLACES:

YOU CAN PLAN WITH THAT

Lineu Castello & Ira Regina Castello

Introduction

Our senses are local, while our experience is regional. So the discussion will cover things as

large as air basins and freeway systems and as small as sidewalks, seats, and signs

(LYNCH 1978 p.10). Such were the words that Kevin Lynch employed in his celebrated

essay, dated of 1976, in which he envisages the possibilities for managing the sense of a

region, and so, to enhance what he understood as the sensory quality of a region. Probably,

this visionary thought seems to still hold true, even in present times, around thirty years after

it was firstly stated. As a matter of fact, the reasoning behind this statement actually supports

the theoretical background that underlies the present paper. In the paper, the prevalent

reasoning is based on the assumption that a sharing of common attributes can be

recognized as inherent to all (or at least to most of) the settlements that comprise an urban

region. This is so because these attributes lie at the very rootedness of the regions centres,

assigning them a somehow distinguishable pattern that, in the end, becomes responsible for

marks that evince the linkage each centre establishes with the region. In this case, perhaps

the best term to express this connectedness is undoubtedly rootedness. The authors are

borrowing this expression from the writings of the classic humanist geographer Yi-Fu Tuan,

who describes the concept as: Rootedness is an unreflective state of being in which the

human personality merges with its milieu (TUAN 1980 p.6). This is what is precisely

meaningful for the purposes of the paper: to acknowledge the existence of a sort of

amalgamation that develops from the interactions between people and environment. The

manifestation of a people-environment fusing will be assumed as a basic issue in the paper

arguments. Moreover, this sort of interacting also lies at the basis of the concept of place, a

concept that will be often called throughout the papers contentions, and whose main lines

explain that A good place is one which, in some way appropriate to the person and her

culture, makes her aware of her community, her past, the web of life, and the universe of

time and space in which those are contained. (LYNCH 1982 p.142). Accordingly, places that

constitute a region, irrespective of their physical scales, will convey intrinsically mutual

characteristics, which will work towards labelling all places under a regional umbrella-like

unifying identity. Or, in other words, will gather them within a system collectively

characterized by the regional rootedness of places.

It is the assumption of the paper that the identification of a regional rootedness of places may

work as a positive factor enhancing the possibilities for planning the regions development.

The paper will attempt to substantiate this conviction by examining pragmatic manifestations

that will help to show that the rootedness of places is not merely a theory. In particular, two

constellations of urban places in the hilly Serra Gaucha region, in the Brazilian state of Rio

Grande do Sul, are significant insofar as the rootedness of places is concerned. United by

common roots, the regions settlements show that there are grounds to believe that this

rootedness not only does exist in the real world but does also help to enhance the attempts

to governing and managing a territory run as an urban region.

A regional dimension for the concept of place

As information technology shortens time-space distances, it contributes to accelerate the

globalisation process todays world engages in, thus creating homogenized environments

that rapidly replicate themselves in a worldwide scale. Therefore, the importance of a

regionalized system of places, formed by individual localities that retain their identifiable

character though constantly subject to a massive exposition to intense global flows,

represents an inspiring achievement. This seems to be the case with the regions discussed

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

2

further below. But before doing so, it seems important to debate the extended dimension the

concept of place is receiving in todays discussions.

Though a theoretical construct of the area of spatial studies, places, in the real world, is a

concept that operates at the crossroads of current social, political, economic, and

environmental issues. Notwithstanding, it is people and their use of the environment that

contribute, over time, to the differentiated status a place can attain in a city, in a region, in an

urban region. There are two clauses in the previous sentence that demand closer attention.

One is the inference that a joining process agglutinating people and their use of the

environment is in action in the genesis of a place. Therefore, places may be said to result

from the interaction between a community and their collective use of space, which, in turn,

implies that places are a social construct. And the other is the expression over time, which

implies the presence of historic factors which lay deeply imbricated within the concept of

place (and that remain immerse during the process of pragmatic creation of the place as

well). Therefore, the influence of memory may be seen as an important factor in the genesis

of a place, since memory evokes on the recondite domains of the regional communitys

cognition, intertwining social, historical, and psychological components into a places

significance. In fact, it is from their regional rootedness that places become originally

structured - physically and subjectively. The manifestation of this regional influence in a

places creation is also acknowledged in philosophical terms, which state () creation

consists in the production of particular places out of pre-existing regions () (CASEY 1998

p.35). There is a common acceptance, then, that a place is layered with the symbolic

attributes that evoke the role this place played in some of the most significant times the

region has experienced. Consequently, the roots shared in common throughout the places of

a single region have an influential role to perform in the definition of the regions future.

New trends for regional planning in Brazil

Despite several well-intentioned efforts, one cannot say that regional planning is a successful

practice in Brazil, and new trends are strongly demanded in the area. Although a practice

dating from the second half of the twentieth century, it never really achieved satisfactory

pragmatic implementations

1

. Most of the plans produced at that time were basically

analytical, often following extensive technical examinations, but in the end, not capable to

present any straightforward guideline, ready for prompt implementation. Additionally, most

policies were not accompanied by design outlines, thus bringing severe difficulties for their

accomplishment when applied to the local level. In fact, as a general rule, local governments

are unprepared, or not used to, to take the politically charged regional decisions that are

engulfed within the plans. Therefore, regional planning in Brazil progressed slowly and has

been rather ineffectively in its attainments. Incidentally, elsewhere in the world, with few

exceptions, the regional planning scenario was not entirely different. In the United States, for

example, Attempts to foster regional planning have a long history. Sadly, the story is not a

thrilling one: with some notable exceptions () it is typically a succession of false starts and

disappointed hopes (CULLINGWORTH & CAVES 2003 p.56). Naturally, successful

exceptions can be pointed out, mostly the ones whose objectives aimed at developing

undeveloped or impoverished regions (of which, the Italian Mezzogiorno, the Brazilian

Northeast SUDENE, and the North-American Tennessee Valley Authority seem to provide

satisfactory examples); or at smoothing the excessive urbanisation of certain areas (like in

the New Towns policies). Surely, also among the exceptions is mandatory to include some of

the so-called world cities. This term, christened by Patrick Geddes as early as 1915, refers

to what he envisaged as the greatest urban agglomerations of his time: the first urban

regions formed by a conurbation of urban centres surrounding a metropolitan pole. Several

years later, the major metropolises of the world became individually singled out, as listed in

the classic book called The World Cities, by economic geographer Peter Hall (1966):

London, Paris, Moscow, the great city complexes of Holland (Randstad) and the Rhine Ruhr;

and outside Europe, New York and Tokyo. In the extended lists prepared by Hall naming the

worlds metropolitan regions around the year of 1960, only two Brazilian cities were

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

3

mentioned, Rio de Janeiro and So Paulo. Nowadays, however, this situation has been

significantly altered. In the 2000s, over 80% of the Brazilians are now residing in urban

areas, the country became largely urbanised, so as to actually present numerous

concentrations of urban centres, sprawling over regional scales. Worldwide things have

changed dramatically as well, and it hardly seems accidental that ISOCARP - the

International Society of City and Regional Planners - addresses the present 40

th

World

Planning Congress of the Association stating One of the most important transformations

faced by cities at the beginning of the 21

st

century is the emergence of urban regions.

Admittedly, the terms more often used to describe todays collective, spatial forms are

megalopolis, edge city, heterotopia, and cyberspace (LAVIN 1999 p.347). As interpreted

by Garreau, for the particular North-American situation of the novel edge cities their society

is now experiencing, urbanites are already facing a third wave in their urban ways of living:

First, we moved our homes out past the traditional idea of what constituted a city. This was

the suburbanization of America (). Thenwe moved our marketplaces out to where we

lived. This was the malling of America (). Today, we have moved our means of creating

wealth () - our jobs - out to where most of us have lived and shopped (). That has led to

the rise of Edge City (GARREAU 1992 p.4, underlined by the authors). This circumstance

described by the journalist is not far from the increasing number of urban regions we

currently encounter all over the world, and which accompany the homogenized ways of living

produced by globalisation.

Understandably, the emergence of intensive clustering of urban centres and their growing

mutual interdependence pose a difficult challenge to Brazilian planning. Any attempts to

define a pragmatic path aiming at a suitable management of todays numerous urban

regions, represent a welcome and needed topic to the subject of regional planning.

Consequently, even incipient manifestations, likely to introduce a regional thinking into the

planning of a dispersed cluster of urban centres, must be taken into account. This is why the

lessons raised by spontaneous activities actually occurring in certain Brazilian urban regions

are investigated in the paper.

In search for new trends in regional planning, especially on the planning of the newly formed

urban regions, two situations will be examined in the paper. One focuses on the

management initiatives employed in the planning of an urban region known as the

Grapevine region, in which all initiatives are taken under the supervision of formal (private)

agents. The other focuses on the informal activities that are been employed in the

management of a region called the Hortensias region, also stimulated by private agents.

They are both situated in the hilly portion of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, within a

larger geographical region named Serra Gacha (Sierra Gaucha). Either formal or informal,

both cases deal with procedures anchored precisely on the strategic factors related to the

regions cultural roots. So, once understood what we mean by the regional rootedness of a

place, lets move forward to understanding why do we believe that one can plan with that.

The Serra Gacha Region

The scene is the state of Rio Grande do Sul, in southern Brazil. With a population of over 10

million inhabitants, 82% of which living in urban areas, the state enjoys a good socio-

economic status in Brazilian terms. According to data from the IBGEs

2

Census, its gross

domestic product amounted, in 2000, to US$46,290,529,879.00 and the GDP per capita to

US$4,544.00. Social development indicators are also good, with the state showing a low

illiteracy ratio (6%); a coefficient of infant mortality also low (18.3 children per thousand); and

97.5% of the dwellings served with sanitary facilities.

The region was originally populated by a huge bulk of European immigrants, Italians and

Germans, who came to the area in the second half of the nineteenth century. The sierra

gaucha is a region blessed with beautiful landscapes, both natural and cultural. Nature

provided the region with rich and dense vegetation, covering the hilly undulated scenery and

establishing delightful panoramic vistas. The immigrants, attracted by the temperate zone

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

4

climate and by the mountainous features predominant in the region, soon founded there a

flourishing occupation, tinged with a rich cultural blending. Two different clusters of urban

regions are highlighted in the paper: the Grapevine and the Hortensias regions (FIG.1).

Figure 1 - The map of Rio Grande do Sul showing the Grapevine and Hortensias Regions.

Source: elaborated by the authors on INTERNET base map.

In certain parts, the scenery is very reminiscent of European regions, either by the natural

features or by the cultural manifestations. The strong influence, especially Italian and

German, made the region a different place from the rest of the country. Furthermore, Rio

Grande do Suls subtropical weather is responsible for precise distinctions among the four

seasons, imparting to the sierra region the rare spectacle of snowfalls in winter, a curiosity

for the rest of the country (FIG.2). However, not only the snow attracts attention elsewhere in

Brazil. Germans and Italians brought with them their recognized disposition to work, and also

all their practices, their shared knowledge, and their common values. Their adaptation to an

alien territory resulted in the thriving of an extremely rich and varied culture, characterized by

particular tastes in arts and manners. Traditional architecture, traditional foods, traditional

drinks, in short, traditional roots, ended up by differentiating the region and furnishing the

grounds for marking the special character it eventually attained.

Figure 2- Snowfalls in Gramados Lago Negro. Source: Zero Hora Newspaper

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

5

The formal management of the Grapevine Region

The Grapevine Region, colonized by Italian immigrants in the end of the nineteenth century,

comprises 25 municipalities where Italian ethnicity is absolutely prevalent. Proud of their

origins, citizens cultivate their roots through the preservation of the habits, customs,

traditions, gastronomy, and even through the dialect veneto (the same of the first

immigrants), that can be listened in the streets. The population of the region summed up

728,000 inhabitants, occupying an area of 7,040km

2

(IBGE Census of 2000).

Its management as a region started with an informal proposition attributed to a former

resident, who had migrated to the states metropolitan capital, Porto Alegre (SEBRAE 2003).

In 1980, returning to his hometown, Bento Gonalves, he wondered why the region was not

being able to retain the intensive rural exodus it was experiencing. Propertys abandonment,

loss of cultural identity, socio-economic depression, marked the scenery among the Italian

descendants, mainly youngsters. Furthermore, former tourist activities experienced an

agonising decline, as the hotel run by his parents was showing. A casual experience led him

to what could be an alternative to that dismal scenery: he toured the hotels guests to a visit

to the neighbouring vineyards. The visit turned out to be such a success, that he perceived

that the cultural rootedness of the region still presented a strong tourist appeal. This initial

finding precipitated a series of connected actions, triggering a successive flow of events.

First, it was created the brand Vale dos Vinhedos (Grapevine Valley), followed by the

inauguration of ATUASERRA (the Tourist Association of the North-eastern Sierra). Some

years later, in 1998, a covenant was signed between ATUASERRA and SEBRAE, the

Brazilian Service of Support to Micro and Small Enterprises

3

. The first work of the recently

established joint venture started by processing a thorough examination of all business

opportunities that already existed in each of the municipalities

4

. It followed the launching of a

special project aiming at the development of Tourism, Agribusiness and Craftsmanship

activities, working under the orientation of a Management executive group. Besides

ATUASERRA and SEBRAE, the managing council included also representatives of some of

the municipal governments (including two of the Mayors, and several Tourism and/or

Agriculture Secretaries); members of the Hotels and Catering Services Union; the Federal

University of Rio Grande do Sul (in charge of establishing a formal registered control for the

wine production, known as D.O.C

5

); and the University of Caxias do Sul

6

(in charge of

establishing specific educational services, including a Bachelor and Master degrees in

Tourism).

Curiously, the greatest emphasis of the project focused on the rural development of the

region, seeing the rural-urban continuum as an integrated development unit. In effect, therein

lies a determining aspect of an urban regions planning. In particular, in the case in point, this

focus proved highly strategical, mainly because: (i) the region is densely urbanised (84% of

the population); (ii) the projects intention is to work in close association with the micro and

small entrepreneurs interests; (iii) it aims at increases in the number of jobs and in the

average incomes; (iv) a major proposal is to attain an upgrading in the quality of regional

services and products; (v) it emphasises the growth of regional businesses and the formation

of partnerships among the regional actors. Obviously, important consequences may result

from this sort of procedure, such as preventing the rural exodus, providing new job

opportunities for the natives, keeping them rooted to their cultural and natural environment

joining the company of their families and their community, and increasing their self-esteem.

In general terms, this tends to further the environmental sustainability through a harmonic

development of the regional places, both rural and urban.

The informal management of the Hortensias Region

The Hortensias Region is an example of a successful partnership established between four

municipalities - four places - symbolically representative of the regions assets. Even if the

findings described here derive from informal entrepreneurial initiatives, in which municipal

agents act freely, manifestations of a collective nature may be singled out. Through a series

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

6

of strategic projects these places managed, over time, to get together, in order to promote

the most distinguished attribute they share in common, their environmental heritage.

Surrounded by a beautiful, mountainous landscape, the places, formerly tiny trade areas

supporting the colonial hinterland occupied and exploited by Italian and German migrants,

eventually developed as winter vacation resorts. The four municipalities spread over a

geographical area of 4,117km occupied by just over 100,000 inhabitants. Although most of

the population concentrates in urban areas (80%, in 2000), the overall population density is

quite low, about 26 persons/km. This situation results, in part, from the relative wilderness of

the municipality of So Francisco de Paula, whose huge territorial boundaries occupy

roughly 80.7% of the regions whole area.

So Francisco de Paula (12,269 persons in the urban area), in spite of its scarcely

occupied territory, is one of the oldest places in the State of Rio Grande do Sul. Its origins

date from the eighteenth century, when Brazilians from So Paulo firstly managed to enter,

explore and eventually, occupy, the southern territories of Brazil. At that time, the area was

just an advanced post for the stopovers of the cavalry trails, though an incipient urban

settlement was already present, providing catering and trading services. Soon the area got

fractioned, subdivided into cattle raising ranches. Eventually, the urban area evolved into an

authentic gauchos

7

place. As such, it presents the traditional features usually associated to

the gaucho image, that is to say, showing all the well known signs displayed by this ethnic

type, such as the typical bombachas they are used to wear, their feeding habits based on

eating red meat in the form of churrasco (barbecue), the matte tea they are used to drink

in special cups, as well as their rodeos and cultural festivals, that add to the distinctiveness

that characterises the southern Brazilian cattleman (FIG. 3). These features, allied to the

temperate climate and the splendorous scenery, attracted, since the early times, people

prone to take a quiet, cheap and distinctly holiday period in very simple hotels and vacation

resorts.

As the states territorial occupancy went on, the official colonization fronts that populated the

region turned to So Francisco de Paulas adjacent territories. Ultimately, this set the trend

for the Sierra Gacha general occupation and, more precisely, for siting the places known

today as Canela, Gramado and Nova Petrpolis.

Figure 3 - Typical gauchos in front of the native pine-tree (Araucaria brasiliensis), and a

monument to the sipping cup for drinking matte. Source: Convention & Visitors Bureau

Canela (30,760 urban residents), the closest municipality to So Francisco de Paula, shows

today a mix of influences resulting on the one hand, from the primordial localization of

Brazilians farms that characterized So Francisco; and, on the other hand, from the colonial

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

7

immigrants occupations. As a consequence the place is ethnically mixed today, revealing its

multi-cultural original influences. It is very Italian in matters such as the food served to

tourists, relying strongly on homemade pasta and polenta; but one can also encounter a real

dressed-up Gaucho on horse back in his daily life activities; or enter into a replica evoking

German architecture, as the stone gothic cathedral planted amidst the central park of the

city, a monument to peoples religiosity, side by side to quite simpler timber Italian buildings

(FIG. 4).

Figure 4 - A blend of Italian, German and gaucho cultures. Photos: L. & I. Castello

Gramado (23,328 urban residents), a straightforward product of the European colonization

is, nowadays, a renowned tourist centre and probably the best-known tourist town attracting

people from outside the state of Rio Grande do Sul. Initially a modest vacation spot, it soon

grew into a reputed holiday resort, offering several tourist attractions. In the last years, the

town experienced a remarkable growth, close accompanied by important investments in the

real estate business. The introduction of varied tourist activities, followed by sound marketing

strategies, rapidly transformed Gramado in a requested place. A curious feature the town

displays, though, is the intentional resemblance of its architecture to that of a European

alpine village. Tyrol roofs, Swiss chalets, Bavarian gables, engraved friezes, the whole lot of

alpine artefacts intertwine in Gramados urban landscape so as to produce a patchwork of

architectural styles, to the enchantment of visitors (and despair of architectural scholars).

Moreover, the fantasy does not end in the real scale architectural elements of the town.

Among the favourite spots there is an outstanding Enchanted-world Park, exhibiting a

miniaturized reproduction of the Hortensias Region colonization. The Palace of the

Festivals, an immense edifice in the style of Italian Alps buildings, placed in the main street

of Gramado, is the major headquarters of the Annual Movie Festival, which draws

competitors from all over Latin-american and Iberian countries. The Lago Negro, the Black

Lake, an artificial lake and one of the most visited points in town, has its name taken from

Germanys Black Forest, simply because it is surrounded by luxuriant woodland composed

entirely of exotic plants that duplicate the species found in the famous German forest. This

same exotic vegetation is also found in another man-made lake, the Joaquina Bier (Fig.5).

Both Canela and Gramado are now experiencing a booming in the real estate sector,

through the rapid growing industry of condominiums, gated communities designed

according to the local thematic architecture.

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

8

Figure 5 - Joaquina Bier Lake and Gramado Main Street: even an old-fashioned bus for touring

the countryside adds magic to the local fantasy. Photos: I. & L. Castello

Nova Petrpolis (12,208 urban residents) is a charming little place situated in the centre of

the provincial colony founded in 1858. Carefully planned to allocate the German immigrants,

the territory was initially partitioned into allotments of equivalent size (roughly 50ha), assisted

by colonial settlements distributed at every 10km. Centrally located, the colonial

administrative seat was designed accordingly, and assigned as a Stadtplatz (city place) to

perform the management of the colonial area. Taking advantage of: (i) the short distance to

Porto Alegre, the states capital city (about 90km.); and of (ii) the high accessibility provided

by the bordering road (the first cross country connection opened in Brazil), the zone soon

managed to attract economic activities, generating an upgrade in the local standards. The

signs of the Germanic culture are found everywhere in the municipality (FIG.6).

Figure 6 - German architectural and landscape signs. Photos: Germano Schr & Convention

& Visitors Bureau

This brief description of the four places united through the partnership called Hortensias

Region shows both, the similarities that helped to put them together, and the diversity they

imply. All four places certainly share the same geographical region, all present a temperate

climate with cold (and sometimes) white winters, exhibit a spectacular landscape, with

mountains, valleys and waterfalls. Moreover, they also have in common the capacity to

maintain signs and cultural manifestations representative of their origins, i.e. they manage to

keep their roots still quite visible. Nonetheless, each place creates its own history, traced by

the action of people over the land, over a period of time, and over a common colonial

background, evolving into distinctive patterns that enlighten and enrich the regional context

as a whole.

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

9

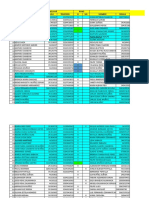

The economic strength of the region comes from activities associated to the tourist sector. As

Chart 1 shows, besides manufacturing of food, textiles, tourist souvenirs and handcraft

goods, activities such as retailing, food & catering, real estate and building are responsible

for the greatest part of the regional economy. Chart 2 displays, for the food & catering sector,

the share of each municipality in the total number of employees, from 1998 to 2001.

Chart 1 - Hortensias Region Economic Activities, 2001

21%

44%

14%

3% 8%

7%

3%

manufacturing retail food & catering warehouse

real estate building others

Source: IBGE, Cadastro Central de Empresas

Chart 2 - Hortensias Region: food & catering employees

386 487 866 932

951 1.029

1.905 2.049

224 249

263 282

148 172 201 244

1998 1999 2000 2001

year

n employees

Canela Gramado Nova Petrpolis So Francisco de Paula

Source: IBGE Database

The informal planning actions that actually take place in the urban region function under the

advisory management of a tourist entity, the Convention & Visitors Bureau of the Hortensias

Region. A non-profit civil association, this entity congregates mostly enterprisers of the

tourist sectors, such as, hoteliers, caterers and festival organizers. Their major purpose is to

develop tourist activities, creating, supporting and attracting them to the region. For this

purpose, they plan an annual calendar of events, and set them in action through coordinated

strategic marketing policies

8

. The regional association started, in fact, as a joint venture of

only two places, Gramado and Canela. This goes back to the 1990s, when Gramado,

already a sound tourist town, envisaged the potential benefits of expanding the tourist area

and, consequently, to amplifying the tourism oriented assets and facilities existing in the

region. The natural course for the accomplishment of this strategy was surely to contact

Canelas enterprisers, since the places stand only 7 kilometres apart. So the informal

association got started and a monument celebrating the union was erected in the bordering

line of the two municipalities. The monument displays two human beings shaking hands

the cultural union and sharing a bouquet of hortensias, the exotic flower that - as the

immigrants - was transplanted into the region and performed so well that it became a

regional symbol (FIG. 7).

Figure 7 - A monument in praise of the integration, located alongside the roadway linking

Gramado to Canela, marks the association of the Hortensias Region. Photo: INTERNET.

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

10

In order to aggregate diversity, the association expanded along a regional axis, eventually

including So Francisco de Paula to the east (and the Gauchos roots it represents); and

Nova Petrpolis to the west (and the Germanic atmosphere it symbolizes). Actually, the four

places stand over a strip alongside some 70 kilometres apart, which defines the core of the

Hortensias Region (FIG.8).

Figure 8- The Hortensias Region strip. Source: INTERNET

What planners have to learn

As the earlier sections of this paper suggest, planning can extract from the internal texture of

an urban region - that is to say, from the places that configure that region - strategic factors

that offer fresh directions for the design alternatives that may enhance the regions

development.

Although part of the evidence for this reasoning lies within the realm of subjective

conjectures there is all possibility, indeed, that the identification of those factors demands a

thorough dissection of the rootedness that has earlier determined the genesis of the places.

Therefore, it seems reasonable to argue that, to parse on the collective rootedness that

underlies the regional network of places will surely help to glide along the tracks of decision,

and hence, establish the managerial bases for an adequate regional governance. Such a

procedure will avail to face one of the important questions that vex our times, the correct

management of the complex task of planning an urban region. However, it is important to

remember that the study of actual urban regions is still at an embryonic stage and that, as

explained by CALTHORPE & FULTON (2001 p.104), Each region has i ts own history,

ecology, geography, economy, political framework, and social and cultural backdrop. This

means that the Regional City will take many forms, adapting itself to the conditions of each

region as appropriate.

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

11

Even a cursory review of the two cases presented shows that the management of both

regions examined demanded (and resulted) from a thorough insight into the rootedness of

the regions constituent places. It is also interesting to note that all places matter: big,

medium, small, micro, urban, rural, indicating that the region must be conceived as a unit.

Furthermore, an urban region represents, today, a new human locus of attachment: one

pertains to a region. In fact, it is crucial to observe that people see themselves nowadays (as

it happened in former historic times) more closely tied economically, and more intimately

socially identified with a region, than with the state, as their main referential entity.

The Grapevine Region case shows that tourism was the common interface that the regional

dwellers chose as a unifying factor in their goals for an integrated management of the

regional system. However, in order to use tourism as a development strategy, they needed to

warrant the conservation of the regions cultural assets, to guarantee the preservation of the

natural resources, and to assure the maintenance of the regional diversity in all its forms,

either on the offer of a balanced mix of leisure activities, either on the blending of the goods

that can be regionally produced. In other words: they stimulated the regional sustainability.

They also needed a project. This is perhaps one of the most important points to underline

here: they realized that they needed to follow the lines launched under an organized path,

put forward through the directives of a project. This is why they saw the creation of a non-

governmental agency as a tool to bring forward a renewed oxygenation for their purposes;

purposes that were already embedded in the regional rootedness. But, that to become

effective would require, from each and every community, their efforts on learning how to

become regionally articulated, so as to profit from the businesses opportunities that only

regional partnerships are able to produce. Today they benefit from the accumulated

knowledge that a project may gather in terms of the planning, organizational, informational,

administrative and technological advisements necessary to make their purposes true. The

Grapevine experience is very recent; the project was launched as early as in 1998.

Nevertheless, some good results may be already evinced. Whatever else it may have

introduced, the project has opened opportunities for approaching, in a simultaneous manner,

a number of regional features scattered over the whole regional system. In this way, a varied

spectrum of scales got correctly contemplated, starting from the macro regional pole, the city

of Caxias do Sul and its mature industrial power; to the micro locality and the modest

handicraft performed by the natives. The mutual advantages are clear. While Caxias do Sul

offers a prodigal educational system, both technical and professional, specialising human

resources in agribusiness, catering, hotel management, tourist services, arts and crafts, and

whatever else the region specifically demands for, the small centres keep the natives

attached to the local production, slackening the flux of rural people who migrate to Caxias do

Sul in search of job opportunities.

The Hortensias Region case is even youngest: it dates approximately to the year 2000. The

major topic is again tourism, but their approach to tourism is rather different. They

concentrate on the diversity sought after by tourists, and manage to offer them a balanced

sample of the rootedness flavour noticed all over the region. So, their proposal for a

harmonic tourist product combines a necessary sample of all the traditional characteristics

the region presents. Plainly put, the cultural and natural elements that best represent the

regions rootedness - real or fake - are put at the service of tourism, even if under the form of

a theme park. As a matter of fact, in the Hortensias region, rootedness is for sale. The early

twenty-first century is bringing to the region a radical change in their managerial practices.

The regions management shows traces of what is actually known as postmodern urbanism,

that is to say, it combines the practices of creating places - placemaking - to the

mechanisms of selling the places - placemarketing - thus created. The trendy world of

theme parks became entirely absorbed among the regional decision-makers practices, which

regard them as a sure and profitable source of economic turnover. The creation of the

Convention & Visitors Bureau helps to expand their intuitive knowledge on tourist,

entertainment, and catering matters. The energetic pace the council adopts is managing to

elaborate a tasty seasonal calendar of events that keeps visitors busy all year round.

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

12

Thenceforth, the planned marketing of the rootedness continued to foster new and innovative

directions for the management of the four places as an urban region.

As for the results that have been already achieved, the four municipalities experienced a

remarkable increase in their economic growth. Job opportunities also increased, as Chart 3

demonstrates, despite the general recession the country faced at that time. As expected, the

growth occurred in the categories more closely associated to tourism, establishing a sort of

chain effect in the offer of employment, linking the catering sector to the accommodation

services, as well as to the construction and to the real estate areas. Furthermore, there was

also a general raise in the average incomes, shown in Chart 4, producing an upgrade in the

standard living conditions, founding a virtuous cycle of economic growth-cum-economic

development.

Chart 3 - Hortensias Region employees

Building

Retail

Food &

Catering

Real Estate

Transport

0

2.000

4.000

6.000

8.000

10.000

12.000

14.000

16.000

1996 1998 2000 2001

year

n

e

m

p

l

o

y

e

e

s

Source: IBGE Database

1996

1998

2001

38

55

32

14

19

30

24

13

20

31

20

9

0

50

100

150

R

$

1

,

0

0

0

.

0

0

year

Chart 4 - Hortensias Region wages

Canela Gramado Nova Petrpolis So Francisco de Paula

Source: IBGE, Cadastro Central de Empresas

The Hortensias Region today counts with a variety of locales specializing in the selling of

the cultural and natural roots. One can choose whether to visit the reproduction of a German

village in Nova Petropolis or the replica of the early urbanization of Gramado-Canela in the

strip that links the two centres, or yet, to attend a rodeo performed by typically dressed

gauchos in the farms of So Francisco de Paula. The mouth also sells tradition. Local food

is a famed attraction so as the equally famed restaurants, rodizios

9

and galletos

10

;

homemade chocolate is another temptation; and the so-called colonial coffee is a gluttony

that overindulges craving tourists. Tradition is also present in the selling of the traditional

Gramados furniture, exported to all parts of the country; the traditional Sierras knitwear,

manufactured in the local mills; and also in the retailing of a paraphernalia of souvenirs, dolls,

home-made liqueurs, crafts, and whatever. Indeed, no matter what, the regions rootedness

sells extremely well, and became a model in administrative terms. In fact, the regions

management is presently administering the selling of locality, but it is doing so according to

the lessons learned through technicalities that postmodern globality taught them to adopt.

Perhaps an illustration of that is the present growth of the new gated communities that are

invading the realty business.

In short, among all the points that have been commented, the ones that deserve to be

highlighted in a synthetical review seem to be: the offer of education (the existence of a

regional University); the construction of a regional brand (ascribing powerful labels to

products such as tourist services, wines and crafts); and the presence of consultive

associations, that work under the auspices of the private sector. These are the main strategic

factors that are bringing favourable results in terms of: (i) tourist development; (ii)

preservation of cultural heritage; (iii) upgrading living standards. All results have close links to

the rootedness that defines the regions places, which is used as a planning strategy either

for fixing people to the internal privatopias of their cultural niches; or to introduce them into

the heterotopias of a changing postmodern way of living.

Lineu Castello & Ira Castello, The Regional Rootedness of Places: you can plan with that

40

th

ISoCaRP Congress 2004

13

References

CALTHORPE, Peter & FULTON, William (2001). The Regional City. Planning for the End of

Sprawl. Washington: Island Press.

CASEY, Edward (1998). The Fate of Place. A Philosophical Story. Berkeley, CA/London, UK:

University of California Press.

CULLINGWORTH, Barry & CAVES, Roger (2003). Planning in the USA. Policies, Issues and

Processes. London and New York: Routledge.

GARREAU, Joel (1992). Edge City. Life on the New Frontier. New York: Anchor

Books/Doubleday.

HALL, Peter (1966). The World Cities. London: World University Library.

LAVIN, Sylvia (1999). The Megalopolis and the Digital Domain. In PHILLIPS, Lisa, The

American Century: Art & Culture 1950-2000. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art,

pp.347-348.

LYNCH, Kevin (1976). Managing the Sense of a Region, Cambridge, MA/London, UK: The

MIT Press.

LYNCH, Kevin (1982). A Theory of Good City Form. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

SEBRAE (2003). A volta ao passado como garantia do futuro (Return to the past as a

guarantee for the future). In VEIT, Mara (Org.) Historias de Sucesso. Belo Horizonte,

Brazil: SEBRAE-Servio de Apoio s Micro e Pequenas Empresas (Support Services for

Micro and Small Enterprises).

TUAN, Yi-Fu (1980).Rootedness versus Sense of Place, Landscape, Vol.24, pp. 3-8.

1

There are only three official administrative Government levels in Brazil: the Nation, the States, and

the Municipalities. The regional level is not an administrative one, just a geographical division.

2

IBGE: Brazilian National Geographical and Statistical Institute.

3

SEBRAE is a private association that fosters entrepreneurial activities and is sponsored by national

enterprisers.

4

The survey visited 939 establishments and perceived opportunities in 359 of them. Criteria for

approving them were based on the assessment of the natural and cultural heritage elements they

possessed, and on the possibilities for the expansion of existing agribusinesses and artisans

craftsmanship.

5

The D.O.C. seal (Denominazione di Origine Controllata), as its equivalent, the French A.O.C.

(Appellation d'Origine Contrle) guarantees that a high standard is achieved in the production of

fine wines, as the ones produced in the region.

6

UCS, the University of Caxias do Sul, offers several units dispersed over the region. Its catchment

area reaches a vast extension, and expands over a regional level. Besides, it also provides for the

transportation of students from their different municipalities.

7

Gacho is the name by which the residents in the state of Rio Grande do Sul are known. They are

frequently seen as the cowboys of the South American pampas. In the Sierra Gaucha case, they

would represent a sort of pampas over the hills cowboys.

8

Among the planned events, the following examples can be mentioned: rodeos, winter fashion

festivals, summer musical fairs, photograph workshops, various Conferences and Congresses,

furniture show, ecological mountain bikes, international shoes and leather fair, Easter magic, knit

fashion, puppeteers festival, Latin-american cinema festival, Deutsche Weinachten, Christmas Lights.

9

A diversity of grilled meats, served in continuous rounds, usually in restaurants called churrascarias

(barbecues).

10

Restaurants specialized in serving grilled galleto al primo canto (young chickens).

You might also like

- The Meanings and Making of Place - Exploring History, Community and Identity (Kong & Yeoh)Document20 pagesThe Meanings and Making of Place - Exploring History, Community and Identity (Kong & Yeoh)eri shopping100% (1)

- Spatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElementsDocument19 pagesSpatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElementsETHAN YEO WEI CHENGNo ratings yet

- Spatialities and Temporalities of The Global - Elements For A TheorizationDocument18 pagesSpatialities and Temporalities of The Global - Elements For A TheorizationJuan IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Spatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElemeDocument19 pagesSpatialities and Temporalities of The Global ElemeCatarinaNo ratings yet

- 1984, Pred1984, Place As Historically Contingent ProcessDocument19 pages1984, Pred1984, Place As Historically Contingent ProcessArwa E. YousefNo ratings yet

- Harris - Modes of Informal Urban DevelopmentDocument20 pagesHarris - Modes of Informal Urban DevelopmentbregasNo ratings yet

- The Future Has Other Plans: Planning Holistically to Conserve Natural and Cultural HeritageFrom EverandThe Future Has Other Plans: Planning Holistically to Conserve Natural and Cultural HeritageNo ratings yet

- Paasi 2000 Reoconstruindo Região PDFDocument9 pagesPaasi 2000 Reoconstruindo Região PDFLucivânia DageoNo ratings yet

- From Space To Place-The Role of Space and Experience in The Construction of PlaceDocument14 pagesFrom Space To Place-The Role of Space and Experience in The Construction of PlaceIvana KrajacicNo ratings yet

- 220 Landzelius Contested Representations Signification in The Built Environment PDFDocument24 pages220 Landzelius Contested Representations Signification in The Built Environment PDFJavier LuisNo ratings yet

- Urban Appropriation Strategies: Exploring Space-making Practices in Contemporary European CityscapesFrom EverandUrban Appropriation Strategies: Exploring Space-making Practices in Contemporary European CityscapesFlavia Alice MameliNo ratings yet

- Between Local GlobalDocument10 pagesBetween Local GlobalMiguel LourençoNo ratings yet

- 5440-Texto Del Artículo-25503-1-10-20180621Document20 pages5440-Texto Del Artículo-25503-1-10-20180621Valentina Palacios AriasNo ratings yet

- Warf 2000Document3 pagesWarf 2000Hesti PrawatiNo ratings yet

- Alif Gusti RamadhaniDocument17 pagesAlif Gusti RamadhaniAlif gusti R RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Place As Historically Pred AllanDocument20 pagesPlace As Historically Pred AllanJhonny B MezaNo ratings yet

- Paasi Bounded SpacesDocument13 pagesPaasi Bounded SpacessimonapacurarNo ratings yet

- CFP ISRH Conference India 2024Document5 pagesCFP ISRH Conference India 2024Aiom MitriNo ratings yet

- Setha Low, 1996. Spatializing+CultureDocument20 pagesSetha Low, 1996. Spatializing+Culturema.guerrero1308463100% (1)

- Orum, A.M., Galland, D. and Grønning, M. (2022) - Spatial Consciousness.Document9 pagesOrum, A.M., Galland, D. and Grønning, M. (2022) - Spatial Consciousness.saddsa dasdsadsaNo ratings yet

- MUBI - On TerritorologyDocument21 pagesMUBI - On TerritorologyfjtoroNo ratings yet

- Translocal Geographies Spaces, Places, ConnectionsDocument6 pagesTranslocal Geographies Spaces, Places, Connectionsultra_zaxNo ratings yet

- Spatialities of GlobalisationDocument16 pagesSpatialities of Globalisationjohnfcg1980No ratings yet

- AbramDocument16 pagesAbramMatiz CarmenNo ratings yet

- Placing Names: Enriching and Integrating GazetteersFrom EverandPlacing Names: Enriching and Integrating GazetteersMerrick Lex BermanNo ratings yet

- Around Territories, Bonnemaison PDFDocument17 pagesAround Territories, Bonnemaison PDFEvelyne CornejoNo ratings yet

- Critical RegionalismDocument7 pagesCritical RegionalismBilal YousafNo ratings yet

- Identity and Territorial Character: Re-Interpreting Local-Spatial DevelopmentFrom EverandIdentity and Territorial Character: Re-Interpreting Local-Spatial DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Planning, Space and Resources: PortfolioDocument10 pagesPlanning, Space and Resources: PortfolioLars Von TrierNo ratings yet

- 77 425S 203 PDFDocument21 pages77 425S 203 PDFvigneshNo ratings yet

- Orum, A.M., Kilper, H. and Gailing, L. (2022) - Cultural Landscapes.Document4 pagesOrum, A.M., Kilper, H. and Gailing, L. (2022) - Cultural Landscapes.saddsa dasdsadsaNo ratings yet

- Defying Disappearance: Cosmopolitan Public Spaces in Hong KongDocument22 pagesDefying Disappearance: Cosmopolitan Public Spaces in Hong KongJo JoNo ratings yet

- Tourism Planning and Place MakingDocument22 pagesTourism Planning and Place MakingMadhawiNo ratings yet

- Life Among Urban Planners: Practice, Professionalism, and Expertise in the Making of the CityFrom EverandLife Among Urban Planners: Practice, Professionalism, and Expertise in the Making of the CityNo ratings yet

- Herzfeld-Spatial CleansingDocument23 pagesHerzfeld-Spatial CleansingsheyNo ratings yet

- Betancur, J. J. (2014) - Gentrification in Latin AmericaDocument15 pagesBetancur, J. J. (2014) - Gentrification in Latin AmericaHernán Marín GallardoNo ratings yet

- aLTERIDADES ANTRO PDFDocument69 pagesaLTERIDADES ANTRO PDFJuanito Sin TierraNo ratings yet

- Kearns & Parkinson 2001, Pp. 2103-2110Document8 pagesKearns & Parkinson 2001, Pp. 2103-2110JavierRuiz-TagleNo ratings yet

- The Global CityDocument7 pagesThe Global CityMegha YadavNo ratings yet

- Disciplinary Spaces: Spatial Control, Forced Assimilation and Narratives of Progress since the 19th CenturyFrom EverandDisciplinary Spaces: Spatial Control, Forced Assimilation and Narratives of Progress since the 19th CenturyNo ratings yet

- Construction of Local and Regional IdentityDocument4 pagesConstruction of Local and Regional IdentitySai RamNo ratings yet

- IDENTITY and UD Laura RodriguezDocument8 pagesIDENTITY and UD Laura Rodriguezjéssica franco böhmerNo ratings yet

- Beyond Preservation: Using Public History to Revitalize Inner CitiesFrom EverandBeyond Preservation: Using Public History to Revitalize Inner CitiesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Smith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentDocument18 pagesSmith N - Gentrification and Uneven DevelopmentnllanoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 103.77.44.145 On Fri, 31 Jul 2020 08:05:47 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 103.77.44.145 On Fri, 31 Jul 2020 08:05:47 UTCDipsikha AcharyaNo ratings yet

- The Incredible Shrinking World? Technology and The Production of SpaceDocument27 pagesThe Incredible Shrinking World? Technology and The Production of SpaceJavier ZoroNo ratings yet

- Strange Spaces A Rationale For BringingDocument36 pagesStrange Spaces A Rationale For BringingAnushkaNo ratings yet

- New Geography - ExcerptDocument36 pagesNew Geography - ExcerptindraprasastoNo ratings yet

- Between Geographical Materialism and Spatial FetisDocument10 pagesBetween Geographical Materialism and Spatial FetisibnalhallajNo ratings yet

- Massey LocalityDocument9 pagesMassey Localityelli dramitinouNo ratings yet

- System of Open Spaces and Territorial Planning: Toward A Sustainable DevelopmentDocument10 pagesSystem of Open Spaces and Territorial Planning: Toward A Sustainable DevelopmentheraldoferreiraNo ratings yet

- Brenner Globalisation As ReterritorialisationDocument22 pagesBrenner Globalisation As Reterritorialisation100475180No ratings yet

- The Conceptual Promise of GlocalizationDocument10 pagesThe Conceptual Promise of GlocalizationMonik Salazar VidesNo ratings yet

- Urbansci 04 00007 v2Document14 pagesUrbansci 04 00007 v2licenseless j-dawgNo ratings yet

- 2 - 2 Hillier SpaceIsTheMachine TimeAsAspectOfSpaceDocument19 pages2 - 2 Hillier SpaceIsTheMachine TimeAsAspectOfSpaceKavyaNo ratings yet

- Sarkis, Hashim TheWorldAccordingToArchitectureDocument8 pagesSarkis, Hashim TheWorldAccordingToArchitecturelulugovindaNo ratings yet

- AbstractDocument3 pagesAbstractojasvi gulyaniNo ratings yet

- Ezio ManziniDocument4 pagesEzio Manzinierdiltugce97No ratings yet

- Urban Landscapes SargoliniDocument193 pagesUrban Landscapes SargoliniJose F. Rivera SuarezNo ratings yet

- Johnson1993 Application of The Tourism Life CycleDocument24 pagesJohnson1993 Application of The Tourism Life CycleqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Tourismgovernanceppt 170120102520Document20 pagesTourismgovernanceppt 170120102520qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Ecotourism Opportunity Spectrum (ECOS) PDFDocument10 pagesEcotourism Opportunity Spectrum (ECOS) PDFAnonymous TAFl9qFM100% (1)

- Steventsivele Arobshowcelebratingfoodandtourismforall 190801152641 PDFDocument12 pagesSteventsivele Arobshowcelebratingfoodandtourismforall 190801152641 PDFqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- ASB LN 1 Van Noordwijk Et Al 2001 Problem Definition INRMDocument57 pagesASB LN 1 Van Noordwijk Et Al 2001 Problem Definition INRMqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Petrevska2016 A Double Life Cycle Determining TourismDocument21 pagesPetrevska2016 A Double Life Cycle Determining TourismqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Icot2012presentation 120704101620 Phpapp01Document19 pagesIcot2012presentation 120704101620 Phpapp01qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Isolinabotopromotingagrotourismdevelopmentinacpsids 191106150500Document11 pagesIsolinabotopromotingagrotourismdevelopmentinacpsids 191106150500qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- BC0338 12Document27 pagesBC0338 12qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Fagence2007 The Tourism Area Life Cycle - ReviewDocument2 pagesFagence2007 The Tourism Area Life Cycle - ReviewqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Ci1315 Cpia 131127070821 Phpapp02Document10 pagesCi1315 Cpia 131127070821 Phpapp02qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- 10.3727@154427209789130666 Life-Cycle Stages in Wine Tourism DevelopmentDocument19 pages10.3727@154427209789130666 Life-Cycle Stages in Wine Tourism DevelopmentqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- I 3482 e 01Document11 pagesI 3482 e 01qpramukantoNo ratings yet

- 351-995-1-PB Cultural Hegemony in Colonial andDocument12 pages351-995-1-PB Cultural Hegemony in Colonial andqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Tourism Opportunity SpectrumDocument11 pagesTourism Opportunity SpectrumqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- ASB LN 1 Van Noordwijk Et Al 2001 Problem Definition INRMDocument57 pagesASB LN 1 Van Noordwijk Et Al 2001 Problem Definition INRMqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Wandering On The WaveDocument7 pagesWandering On The WaveqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Environmental Planning in Indonesia PDFDocument91 pagesEnvironmental Planning in Indonesia PDFqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- 1603 - 27012715 Application of Ecotourism Opportunities SpectrumDocument15 pages1603 - 27012715 Application of Ecotourism Opportunities SpectrumqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Aza Standards For Elephant Management and CareDocument29 pagesAza Standards For Elephant Management and CaresnehaNo ratings yet

- Mughal GardensDocument10 pagesMughal GardensAbhishek BurkuleyNo ratings yet

- Tourism Opportunity SpectrumDocument20 pagesTourism Opportunity SpectrumqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- 77 WRVW 272 PDFDocument14 pages77 WRVW 272 PDFFelipe PiresNo ratings yet

- Tourism Opportunity SpectrumDocument20 pagesTourism Opportunity SpectrumqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Remote Sensing: Done byDocument17 pagesRemote Sensing: Done byqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Site Analysis ExampleDocument11 pagesSite Analysis ExampleTuza KutuzaNo ratings yet

- 1202bm1029 ContentDocument12 pages1202bm1029 ContentqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Mass MovementsDocument12 pagesMass MovementsqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Land Suitability Analysis For Maize Crop in OkaraDocument1 pageLand Suitability Analysis For Maize Crop in OkaraqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- VForestDocument36 pagesVForestqpramukantoNo ratings yet

- Case Studies: Piazza Del Campo & PioneerDocument3 pagesCase Studies: Piazza Del Campo & Pioneera4agarwal0% (1)

- Rosewell, MidlothianDocument1 pageRosewell, MidlothianAnonymous MDlEgaQcNo ratings yet

- Masuri de Prevenire A Inudatiilor in Orase in Curs de ExpansiuneDocument7 pagesMasuri de Prevenire A Inudatiilor in Orase in Curs de ExpansiuneMaria StoicaNo ratings yet

- Nature's Metropolis: April 2019Document6 pagesNature's Metropolis: April 2019Martti OlivaNo ratings yet

- Unit Ii - Part 2Document13 pagesUnit Ii - Part 2snehalNo ratings yet

- Handbook Disaster ManagementDocument240 pagesHandbook Disaster ManagementRahul Ramesh100% (1)

- Kiki Andri Sepriansyah - 2003511002 - EAP Assignment - ParagraphDocument2 pagesKiki Andri Sepriansyah - 2003511002 - EAP Assignment - ParagraphKiki Andry Sepriansyah AsNo ratings yet

- CH 5 Practice ProblemsDocument10 pagesCH 5 Practice ProblemsDennisRonaldiNo ratings yet

- Regional Planning IndiaDocument16 pagesRegional Planning Indiaadityaap92% (25)

- CPSD Rwanda PDFDocument127 pagesCPSD Rwanda PDFNgendahayo EricNo ratings yet

- Nueva Base de Datos Ago21Document91 pagesNueva Base de Datos Ago21EderNo ratings yet

- Development Economics - Chapter 7Document9 pagesDevelopment Economics - Chapter 7Joshua Miguel BartolataNo ratings yet

- Notable PlannersDocument98 pagesNotable PlannersDevryl RufinNo ratings yet

- Radiant City and ToDDocument13 pagesRadiant City and ToDVriti SachdevaNo ratings yet

- Envi. Strategies For GujDocument31 pagesEnvi. Strategies For GujVigneswaran Selvaraj100% (1)

- Sustainable Mobility in African CitiesDocument32 pagesSustainable Mobility in African CitiesUnited Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)No ratings yet

- Thesis Draft 1Document11 pagesThesis Draft 1joshua dolorNo ratings yet

- Bmrda Restructure PDFDocument346 pagesBmrda Restructure PDFbasavarajitnalNo ratings yet

- Research Report Bangladesh National Urban Policies and City Profiles For Dhaka and KhulnaDocument156 pagesResearch Report Bangladesh National Urban Policies and City Profiles For Dhaka and KhulnaMehedi Hasan/UDP/BRACNo ratings yet

- Urban Informal Sector - Conceptual Overview: Chapter - 2Document28 pagesUrban Informal Sector - Conceptual Overview: Chapter - 2tejaswiniNo ratings yet

- Social Problems Community Policy and Social Action 6th Edition Ebook PDFDocument62 pagesSocial Problems Community Policy and Social Action 6th Edition Ebook PDFcarolyn.kemper62697% (39)

- The Local Community Leaders PDFDocument22 pagesThe Local Community Leaders PDFReza AkbarNo ratings yet

- Robert Cull, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Jonathan Morduch, Alberto Chaia, Aparna Dalal - Banking The World - Empirical Foundations of Financial Inclusion-MIT Press (2013)Document519 pagesRobert Cull, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, Jonathan Morduch, Alberto Chaia, Aparna Dalal - Banking The World - Empirical Foundations of Financial Inclusion-MIT Press (2013)Ibrahim KhatatbehNo ratings yet

- Remesas BolivarDocument24 pagesRemesas BolivarYani PopayanNo ratings yet

- 9 - Urban & Rural Development in BangladeshDocument21 pages9 - Urban & Rural Development in BangladeshMd Omar Kaiser MahinNo ratings yet

- Transformation of Main Boulevard, Gulberg, Lahore: From Residential To CommercialDocument13 pagesTransformation of Main Boulevard, Gulberg, Lahore: From Residential To CommercialSYED QALBE RAZA BUKHARINo ratings yet

- Questionnaire 1Document2 pagesQuestionnaire 1Romneil D. CabelaNo ratings yet

- East Riverfront Framework PlanDocument46 pagesEast Riverfront Framework PlanWDET 101.9 FMNo ratings yet

- Urbanization and Its HazardsDocument4 pagesUrbanization and Its HazardsHappyKumarLadher100% (1)

- Msoe 4 em PDFDocument6 pagesMsoe 4 em PDFFirdosh KhanNo ratings yet