Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Elvic&yourcore

Uploaded by

atul-heroOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Elvic&yourcore

Uploaded by

atul-heroCopyright:

Available Formats

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

1

Written by Diane Lee BSR, FCAMT, CGIMS

Presentedinwholeorpartatthe:

AmericanBackSocietyMeetingSanFrancisco2005

BCTrialLawyersMeetingVancouver2005

JapaneseSocietyofPosture&MovementMeetingTokyo2006

Introduction

A primary function of the pelvis is to transfer the loads generated by body weight and

gravityduringstanding,walking,sittingandotherfunctionaltasks.Howwellthisloadis

managed dictates how efficient function will be. The word stability is often used to

describe effective load transfer and requires optimal function of three systems: the passive

(formclosure),active(forceclosure)andcontrol(motorcontrol)(Panjabi1992).Collectively

these systems produce approximation of the joint surfaces (Snijders & Vleeming 1993a,b).

Theamountofapproximationrequiredisvariableanddifficulttoquantifysinceitdepends

on an individuals structure (form closure) and the forces they need to control (force

closure). The following definition of joint stability comes from the European guidelines on

thediagnosisandtreatmentofpelvicgirdlepain(Vleemingetal2004).

Definition of Joint Stability

The effective accommodation of the joints to each specific load demand through an

adequately tailored joint compression, as a function of gravity, coordinated muscle and

ligament forces, to produce effective joint reaction forces under changing conditions.

Optimal stability is achieved when the balance between performance (the level of stability)

and effort is optimized to economize the use of energy. Nonoptimal joint stability

implicatesalteredlaxity/stiffnessvaluesleadingtoincreasedjointtranslationsresultingin

a new joint position and/or exaggerated/reduced joint compression, with a disturbed

performance/effortratio.

(VleemingA,AlbertHB,vanderHelmFCT,LeeD,OstgaardHC,StugeB,

SturessonB).

Based on this definition, the analysis of pelvic girdle function will require tests for

excessive/reduced joint compression (mobility) as well as tests for motion control of the

joints(sacroiliac(SIJ)andpubicsymphysis)duringfunctionaltasks(onelegstanding,active

straight leg raise). Motion control of the joints requires the timely activation of various

muscle groups such that the coactivation pattern occurs at minimal cost (minimal

compression or tension loading and the least amount of effort) to the musculoskeletal

system.Analysisofneuromuscularfunctionwillrequiretestsforbothmotorcontrol(timing

of muscle activation) and muscular capacity (strength and endurance) since both are

required for intersegmental or intrapelvic control, regional control (between thorax and

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

2

pelvis, pelvis and legs) as well as the maintenance of whole body equilibrium during

functional tasks. Treatment protocols should include techniques to reduce joint

compression where necessary, exercises to increase joint compression where and when

necessary and education to foster understanding of both the mechanical and emotional

componentsofthepatientsexperience.

Passive System Analysis of the SIJ

For many decades, it was thought that the SIJ

was immobile due to its anatomy. It is now

known that mobility of the SIJ is not only

possible(Egundetal1978,Hungerfordetal2004,

Lavignolle et al 1983), but essential for shock

absorption during weight bearing activities and

is maintained throughout life (Vleeming et al

1992a).Thequantityofmotionissmall(bothfor

angular and translatoric motion) and variable

betweenindividuals(Kissling&Jacob1997).

Thepassivesystem(joint/ligaments)isanalysedbycomparingtheamplitudeandsymmetry

ofmotionbetweentheinnominateandsacrum(Lee2004,Lee&Lee2004)).TheSIJisthen

passively taken into the closepacked position (the position where there is maximum

congruence of the joint surfaces and tension of the articular ligaments) which for the SIJ is

sacral nutation/posterior rotation of the innominate) and the translations are repeated.

When the ligaments are intact and healthy, no translation of the joint should occur in this

closepacked, stable position. In addition, this test should be pain free.If there is increased

motionwhentheSIJisinaneutralpositionandthistranslationpersistsintheclosepacked

position, this suggests that the ligaments have been stretched and a deficit in the passive

system is implicated. This test often reproduces SIJ ligamentous pain. If there is increased

motionwhentheSIJisinaneutralpositionandnotranslationoccurswhenthejointisinthe

closepacked position, this suggests that the force closure or motor control system is

impaired and that there is insufficient (or at least asymmetric) compression of the SIJ in

neutral. Further tests are required to determine the specific deficit in the motor control

system.

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

3

Motor Control and the SIJ

Function would be significantly compromised if joints could only be stable in the close

packed (selflocked or selfbraced) position. Stability for load transfer is required

throughouttheentirerangeofmotionandisprovidedbytheactivesystem(directedbythe

controlsystem)whenthejointisnotintheclosepackedposition.Optimalforceclosureof

the pelvic girdle requires just the right amountof force being appliedat just the right time

(Hodges2003).Thisinturnrequiresacertaincapacity(strength/endurance)ofthemuscular

systemaswellasafinelytunedmotorcontrolsystem,onethatisabletopredictthetiming

of the load and to prepare the system appropriately. The amount of compression needed

depends on the individuals form closure and the loading conditions (speed, duration,

magnitude). Therefore there are multiple optimal strategies possible, some for low loading

tasks and others for high loading tasks. The compression,or force closure, is produced by

anintegratedactionandreactionbetweenthemusclesystems,theirfascialandligamentous

connections, and gravity. The timing, pattern and amplitude of the muscular contractions

depend on an appropriate efferent response of both the central and peripheral nervous

systems which in turn rely on appropriate afferent input from the joints, ligaments, fascia

andmuscles.Itisindeedacomplexsystem,oftendifficulttostudy,yetwhenonereturnsto

the definition of joint stability (the ability to transfer loads with the least amount of effort

whichcontrolsmotionofthejoints)notdifficulttoassessortreat.

A healthy, integrated neuromyofascial system ensures that loads are effectively

transferred through the joints while mobility is maintained, continence is preserved and

respiration supported. Nonoptimal strategies result in loss of motion control (excessive

shearingortranslation)oftenassociatedwithgivingway,and/orexcessivebracing(rigidity)

of the hips, low back and/or rib cage. These strategies often create an excessive increase in

theintraabdominalpressure(Thompsonetal2004)whichcancompromiseurinaryand/or

fecal continence. In addition, nonoptimal respiratory patterns, rate and rhythm can

develop. Often, patients with failed load transfer through the pelvic girdle present with

inappropriate force closure in that certain muscles become overactive while others remain

inactive, delayed or asymmetric in their recruitment (Hungerford et al 2003). These

alterations in motor control must be considered during assessment because if altered, the

systemisnotpreparedfortheloadswhichreachitandrepetitivestrainsofthepassivesoft

tissues can result. In particular, the recent evidence regarding the role of transversus

abdominis, the deep fibres of the lumbar multifidus and the pelvic floor muscles suggests

thattheybesingledout.

Although it does not cross the SIJ directly, transversus abdominis (TrA) can impact

stiffness of the pelvis through its direct anterior attachments to the ilium as well as its

attachments to the middle layer and the deep lamina of the posterior layer of the

thoracodorsal fascia (Barker et al 2004). Richardson et al (2002) suggest that contraction of

the TrA produces a force which acts on the ilia perpendicular to the sagittal plane (i.e.

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

4

approximatestheiliaanteriorly).Inastudyofpatientswithchroniclowbackpain,atiming

delay was found in which TrA failed to anticipate the initiation of arm and/or leg motion

(Hodges & Richardson 1996). This delayed activation of TrA could imply that the

thoracodorsal fascia is not sufficiently pretensed, hence the pelvis not optimally

compressed,inpreparationforexternalloadingleavingitpotentiallyvulnerabletotheloss

of intrinsic stability during functional tasks. Three other studies have shown altered

activationinTrAinsubjectswithlongstandinggroinpain(Cowanetal2004),lowbackpain

(Ferreiraetal2004)andpelvicgirdlepain(Hungerfordetal2003).

Hidesetal(1994,1996),Danneelsetal(2000)andMoseleyetal(2002)havestudiedthe

response of multifidus (deep, superficial and lateral fibres) in low back and pelvic girdle

pain patients and note that the deep fibres of multifidus (dMF) become inhibited and

reducedinsizeintheseindividuals.Itishypothesizedthatthenormalpumpupeffectof

the dMF on the thoracodorsal fascia, and therefore its ability to compress the pelvis

posteriorly,islostwhenthesizeorfunctionofthismuscleisimpaired.

Using the Doppler imaging system, Richardson et al (2002) noted that when the

subjectwasaskedtohollowtheirlowerabdomen(resultinginacocontractionofTrAand

dMF)thestiffnessoftheSIJincreased.Theseauthorsstatethatundergravitationalload,it

is the transversely oriented muscles that must act to compress the sacrum between the ilia

andmaintainstabilityoftheSIJ.Althoughmultifidusisnotorientedtransversely,bothit

and several other muscles (erector spinae, gluteus maximus, latissimus dorsi, internal

oblique)cangeneratetensioninthethoracodorsalfasciaandthusimpartcompressiontothe

posteriorpelvis(Barkeretal2004,vanWingerdenetal2004).

The muscles of the pelvic floor play a critical role in the maintenance of urinary and

fecal continence (AshtonMiller et al 2001, Barbic et al 2003, B & Stein 1994, Deindl et al

1993,1994,Sapsfordet al2001)andrecentlyattentionhasbeendirectedtotheir roleinthe

stabilization of the joints of the pelvic girdle (Lee & Lee 2004b,c,d, OSullivan et al 2002,

PoolGoodzwaard 2003). The research suggests that motor control (sequencing and timing

ofmuscularactivation)playsacriticalroleintheabilitytoeffectivelyforceclosetheurethra,

stabilizethebladderandcontrolmotionoftheSIJduringloadingtasks.

Theactivestraightlegraisetest(ASLR)examinestheabilityofthepatienttotransfer

loadthroughthepelvisinsupinelyingandhasbeenvalidatedforreliability,sensitivityand

specificityforpelvicgirdlepainafterpregnancy(Mensetal1999,2001,2002).Itcanalsobe

usedtoidentifynonoptimalstabilizationstrategiesforloadtransferthroughthepelvis.The

supine patient is asked to lift the extended leg 20 centimeters and to note any effort

difference between the left and right leg (does one leg seem heavier or harder to lift). The

strategyusedtostabilizethelumbopelvicregionduringthistaskisobservedandtheeffort

scoredfrom0to5.Thepelvisisthencompressedpassively(anteriortosimulatetheforceof

TrA and posterior to simulate the force of the dMF (Lee & Lee 2004a,c)) and the ASLR is

repeated;anychangeinstrategyand/oreffortisnoted.

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

5

Subsequently, the patients ability to

voluntarily contract the TrA, dMF and the

pelvic floor is assessed and the results co

related to the findings of the ASLR test. To

assesstheabilityoftheleftandrightTrAtoco

contract in response to a pelvic floor cue, the

abdomen is palpated just medial to the ASISs

and the patient is instructed to gently squeeze

the muscles around the urethra or to lift the

vagina/testicles.Whenabilateralcontractionof

TrA is achieved in isolation from the internal

oblique, a deep tensioning will be felt symmetrically and the lower abdomen hollows

(movesinward)(OSullivanetal2003,Richardsonetal1999).

ThedMFispalpatedbilaterallyclosetothespinousprocessorthemediansacralcrest.

Inahealthysystem,acuetocontractthepelvicfloorshouldresultinacocontractionofthe

dMF (clinical experience Lee & Lee 2004a,c). When a bilateral contraction of dMF is

achievedthemusclecanbefelttoswellsymmetricallybeneaththefingers(Richardsonetal

1999).Thereshouldbenoevidenceofsubstitutionfromthemoresuperficialmultisegmental

fibersofthemultifiduswhichwillproduceextensionofthelumbarspineandaphasicbulge

of the substituting muscle. TrA should coactivate with the dMF and both muscles can be

palpatedunilaterallytoassesscocontractionduringaverbalcuetocontractthepelvicfloor

(clinicalexperienceLee&Lee2004a,c).

The activation patterns of the deep muscle system can also be assessed using

rehabilitativeultrasoundimaging(Henry&Westervelt2005,Lee&Lee2004c,Richardsonet

al1999).Thefigurebelowontheleftisoftherightanterolateralabdominalwallatrestand

the

right illustrates an optimal isolated contraction of the transversus abdominis. During an

optimal, isolated contraction the medial TrA fascia should translate laterally, TrA should

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

6

increaseingirthandthemuscleshouldcorsetlaterallyaroundthetrunkbeforeanychange

ingirthisseenintheinternaloblique(IO).

TheRTUSfigurebelowontheleftisoftherightanterolateralabdominalwallatrestandthe

rightisanonoptimalattempttoisolateacontractionofthetransversusabdominis.Thereis

overactivationoftheinternaloblique(circle)duringthisisolationattempt(notetheincrease

ingirthofboththeTrAandtheIOarrows).Thisstrategyresultsinglobalbracingofthe

abdominalwallandproducesexcessivecompressionoftheribcagewhichinturnlimitsthe

ability to breathe. In addition, this strategy significantly increases the intraabdominal

pressure which can have long term consequences for urinary continence especially in

women.

TheRTUSfigureontheleftisasuprapubic,transabdominalviewofthepelvicfloormuscles

andtheurinarybladderandthefigureontherightistheimpactthatanoptimalcontraction

of the pelvic floor has on the bladder shape. This midline lift suggests that an optimal

contractionofthepelvicfloormuscleshasoccurred.

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

7

Treatmentfortheimpairedpelvicgirdlemustbeprescriptivesinceeveryindividualhasa

uniqueclinicalpresentation.Ultimately,thegoalistoteachthepatientahealthierwaytolive

and move such that sustained compression and/or tensile forces on any one structure are

avoided.Exercisesformotorcontrolareaimedatretrainingstrategiesofmuscularpatterning

sothatloadtransferisoptimizedthroughalljointsofthekineticchain.Optimalloadtransfer

occurswhenthereisprecisemodulationofforce,coordination,andtimingofspecificmuscle

contractions, ensuring control of each joint (segmental control), the orientation of the spine

(spinalcurvatures,thoraxonpelvicgirdle,pelvisinrelationtothelowerextremity),andthe

controlofposturalequilibriumwithrespecttotheenvironment(Hodges2003).Theresultis

stabilitywithmobility,wherethereisstabilitywithoutrigidityofposture,withoutepisodesof

collapse,andwithfluidityofmovement.Optimalcoordinationofthemyofascialsystemwill

produceoptimalstabilizationstrategies.Thesepatientswillhave:

the ability to find and maintain control of neutral spinal alignment both in the

lumbopelvicregionandinrelationshiptothethoraxandhip

theabilitytoconsciouslyrecruitandmaintainatonic,isolatedcontractionofthedeep

stabilizers of the lumbopelvis to ensure segmental control and then to maintain this

contractionduringloading,

the ability to move in and out of neutral spine (flex, extend, laterally bend, rotate)

withoutsegmentalorregionalcollapse,

theabilitytomaintainalltheaboveincoordinationwiththethoraxandtheextremities

infunctional,workspecific,andsportspecificposturesandmovements.

ThefindingsfromtheASLRtest(impactofspecificcompressions)togetherwiththeresults

of palpation analysis of the transversus abdominis and multifidus coupled with the RTUS

findings in response to verbal cuing and the ASLR test help the clinician to determine the

specificmotorcontroldeficitspresentinapatientwithfailedloadtransferthroughtheSIJ.

These tests also facilitate a prescriptive exercise program which is unique to the patients

clinicalpresentation.

More information on the integrated multimodal approach to the assessment and treatment

of the lumbopelvichip region can be found in Lee & Lee 2004b,c, the Discover Phyiso

websiteatwww.discoverphysio.caorRichardsonetal1999,2004.

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

8

References

AshtonMillerJA,HowardD,DeLanceyJOL2001Thefunctionalanatomyofthefemalepelvicfloor

andstresscontinencecontrolsystem.ScandJ.UrolNephrolSuppl207

BarbicM,KraljB,CorA2003Complianceofthebladdernecksupportingstructures:importanceof

activitypatternoflevatoranimuscleandcontentofelasticfibersofendopelvicfascia.

NeurourologyandUrodynamics22:269

BarkerPJ,Briggs,CA,BogeskiG2004Tensiletransmissionacrossthelumbarfasciainunembalmed

cadavers.Spine29(2):129

BK,SteinR1994NeedleEMGregistrationofstriatedurethralwallandpelvicfloormuscleactivity

patternsduringcough,valsalva,abdominal,hipadductor,andglutealmusclescontractions

innulliparoushealthyfemales.NeurourologyandUrodynamics13:3541

CowanSM,SchacheAG,Prukner,BennellKL,HodgesPW,CoburnP,CrossleyKM2004Delayed

onsetoftransversusabdominusinlongstandinggroinpain.Medicine&ScienceinSports&

Exercise,Dec20402045

DanneelsLA,VanderstraetenGG,CambierDC,WitvrouwEE,DeCuyperHJ2000CTimagingof

trunk muscles in chronic low back pain patients and healthy control subjects. European

Spine9(4):266272

DeindlFM,VodusekDB,HesseU,SchusslerB1993Activitypatternsofpubococcygealmusclesin

nulliparouscontinentwomen.BritishJournalofUrology72:46

Deindl F M, Vodusek D B, Hesse U, Schussler B 1994 Pelvic floor activity patterns: comparison of

nulliparous continent and parous urinary stress incontinent women. A kinesiological EMG

study.BritishJournalofUrology73:413

Ferreira P H, Ferreira M L, Hodges P W 2004 Changes in recruitment of the abdominal muscles in

peoplewithlowbackpain,ultrasoundmeasurementofmuscleactivity.Spine29:25602566

HenrySM,WesterveltKC2005Theuseofrealtimeultrasoundfeedbackinteachingabdominal

hollowingexercisestohealthysubjects.JOSPT35(6):338345

HidesJA,RichardsonCA,JullGA1996Multifidusrecoveryisnotautomaticfollowingresolutionof

acutefirstepisodelowbackpain.Spine21(23):27632769

HidesJA,StokesMJ,SaideM,JullGA,CooperDH1994Evidenceoflumbarmultifidusmuscles

wastingipsilateraltosymptomsinpatientswithacute/subacutelowbackpain.Spine19(2):

165177

HodgesPW2003Corestabilityexerciseinchroniclowbackpain.OrthopaedicclinicsofNorth

America34:245

HodgesPW,RichardsonCA1996Inefficientmuscularstabilizationofthelumbarspineassociated

withlowbackpain.Amotorcontrolevaluationoftransversusabdominis.Spine21(22):2640

2650

HungerfordB,GilleardW,HodgesP2003Evidenceofalteredlumbopelvicmusclerecruitmentinthe

presenceofsacroiliacjointpain.Spine28(14):1593

LeeDG,LeeLJ2004cAnintegratedapproachtotheassessmentandtreatmentofthelumbopelvic

hipregionDVD.www.dianelee.ca

Lee D G, Lee L J 2004d Stress Urinary Incontinence A Consequence of Failed Load Transfer

Through the Pelvis? In: Proceedings from the 5th interdisciplinary world congress on low

backandpelvicpain.Melbourne,Australia

Pelvic Stability & Your Core

9

LeeDG,VleemingA1998Impairedloadtransferthroughthepelvicgirdleanewmodelofaltered

neutralzonefunction.In:Proceedingsfromthe3

rd

InterdisciplinaryWorldCongressonLow

BackandPelvicPain.Vienna,Austria

MensJMA,VleemingA,SnijdersCJ,KoesBJ,StamHJ2001Reliabilityandvalidityoftheactive

straightlegraisetestinposteriorpelvicpainsincepregnancy.Spine26(10):11671171

MensJMA,VleemingA,SnijdersCJ,StamHJ,GinaiAZ1999Theactivestraightlegraisingtest

andmobilityofthepelvicjoints.EuropeanSpine8:468473

MensJM,VleemingA,SnijdersCJ,KoesBW,StamHJ2002Validityoftheactivestraightlegraise

testformeasuringdiseaseseverityinpatientswithposteriorpelvicpainafterpregnancy.

Spine27(2):196

MoseleyGL,HodgesPW,GandeviaSC2002Deepandsuperficialfibersofthelumbarmultifidus

musclearedifferentiallyactiveduringvoluntaryarmmovements.Spine27(2):E29E36

OSullivanPB,BealesD,BeethamJAetal2002AlteredmotorcontrolstrategiesinsubjectswithSIJ

painduringtheactivestraightlegraisetest.Spine27(1):E1

OSullivanP,BryniolfssonG,CawthorneA,KarakasidouP,PedersonP,WatersN2003Investigation

ofaclinicaltestandtransabdominalultrasoundduringpelvicfloormusclecontractionin

subjectswithandwithoutlumbosacralpain.In:14thinternationalWCPTcongress

proceedings.Barcelona,Spain,CDROMabstracts

PoolGoudzwaardA2003BiomechanicsofthesacroiliacjointsandthepelvicfloorPhDthesis.

Chapter8:relationbetweenlowbackandpelvicpain,pelvicflooractivityandpelvicfloor

disorders.

RichardsonCA,JullGA,HodgesPW,HidesJA1999Therapeuticexerciseforspinalsegmental

stabilizationinlowbackpainscientificbasisandclinicalapproach.ChurchillLivingstone,

Edinburgh

RichardsonCA,SnijdersCJ,HidesJA,DamenL,PasMS,StormJ2002Therelationshipbetween

thetransverselyorientedabdominalmuscles,SIJmechanicsandlowbackpain.Spine

27(4):399405

SapsfordRR,HodgesPW,RichardsonCA,CooperDH,MarkwellSJ,JullGA2001Coactivation

oftheabdominalandpelvicfloormusclesduringvoluntaryexercises.Neurourologyand

Urodynamics20:3142

ThompsonJ,OSullivanP,BriffaK,NeumannP2004Motorcontrolstrategiesforactivationofthe

pelvicfloor.In:Proceedings5

th

InterdisciplinaryWorldCongressonLowBackandPelvic

Pain.Melbourne,Australia,Novemberp116

VanWingerdenJP,VleemingA,BuyrukHM,RaissadatK2004StabilizationoftheSIJinvivo:

verificationofmuscularcontributiontoforceclosureofthepelvis.EuropeanSpineJournal

13(3):199

You might also like

- Breakfast: Enjoy The One You're With!Document1 pageBreakfast: Enjoy The One You're With!atul-heroNo ratings yet

- Thai Square: City MinoriesDocument16 pagesThai Square: City Minoriesatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Lunch & Early Evening MenuDocument1 pageLunch & Early Evening Menuatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Chef's Special Menu: 1. Micro Green Sashimi $15Document2 pagesChef's Special Menu: 1. Micro Green Sashimi $15atul-heroNo ratings yet

- Thal SinDocument8 pagesThal Sinatul-heroNo ratings yet

- InnerDocument1 pageInneratul-heroNo ratings yet

- Evening Menu: Breads and OlivesDocument1 pageEvening Menu: Breads and Olivesatul-heroNo ratings yet

- The Sadhana of Buddha Amitabha: Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Samma SambuddhassaDocument7 pagesThe Sadhana of Buddha Amitabha: Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Samma Sambuddhassaatul-heroNo ratings yet

- BeenuDocument2 pagesBeenuatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Ocer MeDocument4 pagesOcer Meatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Pites MemerDocument2 pagesPites Memeratul-heroNo ratings yet

- EveninuDocument1 pageEveninuatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Din 2Document1 pageDin 2atul-heroNo ratings yet

- Lumbo-Pelvic Stability and Back Pain: What's The Link?Document8 pagesLumbo-Pelvic Stability and Back Pain: What's The Link?atul-heroNo ratings yet

- The Sadhana of Buddha Amitabha: Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Samma SambuddhassaDocument7 pagesThe Sadhana of Buddha Amitabha: Namo Tassa Bhagavato Arahato Samma Sambuddhassaatul-heroNo ratings yet

- 'Flow' Experiences: The Secret To Ultimate Happiness?: Lance P. Hickey, PH.DDocument7 pages'Flow' Experiences: The Secret To Ultimate Happiness?: Lance P. Hickey, PH.Datul-heroNo ratings yet

- Zoo Run Registration - 2014Document1 pageZoo Run Registration - 2014atul-heroNo ratings yet

- What Is Child Life?: What I'm Not: What I'm Not: What I'm Not: What I'm NotDocument1 pageWhat Is Child Life?: What I'm Not: What I'm Not: What I'm Not: What I'm Notatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Park Entry FeesDocument1 pagePark Entry Feesatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Group Class Schedule SpringDocument1 pageGroup Class Schedule Springatul-heroNo ratings yet

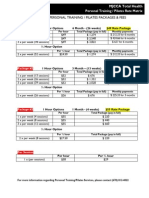

- One-On-One Personal Training / Pilates Packages & Fees: Package #1Document2 pagesOne-On-One Personal Training / Pilates Packages & Fees: Package #1atul-heroNo ratings yet

- The Lost Letter: Prof. Chaman LalDocument5 pagesThe Lost Letter: Prof. Chaman Lalatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Adversity Advantage: Turning IntoDocument1 pageAdversity Advantage: Turning Intoatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Restorative Yoga Yoga Nidra: Janet ParachinDocument1 pageRestorative Yoga Yoga Nidra: Janet Parachinatul-heroNo ratings yet

- The Hand &flowers Wine ListDocument12 pagesThe Hand &flowers Wine Listatul-heroNo ratings yet

- Princess: A True Story of Life Behind The Veil in Saudi ArabiaDocument2 pagesPrincess: A True Story of Life Behind The Veil in Saudi Arabiaatul-heroNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sand Casting Lit ReDocument77 pagesSand Casting Lit ReIxora MyNo ratings yet

- Amnesty - Protest SongsDocument14 pagesAmnesty - Protest Songsimusician2No ratings yet

- John 20 Study GuideDocument11 pagesJohn 20 Study GuideCongregation Shema YisraelNo ratings yet

- DSP Setting Fundamentals PDFDocument14 pagesDSP Setting Fundamentals PDFsamuel mezaNo ratings yet

- Oc ch17Document34 pagesOc ch17xavier8491No ratings yet

- GALVEZ Vs CADocument2 pagesGALVEZ Vs CARyannCabañeroNo ratings yet

- Reading Activity - A Lost DogDocument3 pagesReading Activity - A Lost DogGigsFloripaNo ratings yet

- "Management of Change ": A PR Recommendation ForDocument60 pages"Management of Change ": A PR Recommendation ForNitin MehtaNo ratings yet

- Teacher LOA & TermsDocument3 pagesTeacher LOA & TermsMike SchmoronoffNo ratings yet

- Adv Tariq Writ of Land Survey Tribunal (Alomgir ALo) Final 05.06.2023Document18 pagesAdv Tariq Writ of Land Survey Tribunal (Alomgir ALo) Final 05.06.2023senorislamNo ratings yet

- "The Grace Period Has Ended": An Approach To Operationalize GDPR RequirementsDocument11 pages"The Grace Period Has Ended": An Approach To Operationalize GDPR RequirementsDriff SedikNo ratings yet

- BK Hodd 000401Document25 pagesBK Hodd 000401KhinChoWin100% (1)

- EikonTouch 710 ReaderDocument2 pagesEikonTouch 710 ReaderShayan ButtNo ratings yet

- Compilation 2Document28 pagesCompilation 2Smit KhambholjaNo ratings yet

- Types of CounsellingDocument5 pagesTypes of CounsellingAnkita ShettyNo ratings yet

- The Utopia of The Zero-OptionDocument25 pagesThe Utopia of The Zero-Optiontamarapro50% (2)

- TENSES ExerciseDocument28 pagesTENSES ExerciseKhanh PhamNo ratings yet

- Bca NotesDocument3 pagesBca NotesYogesh Gupta50% (2)

- Derivative Analysis HW1Document3 pagesDerivative Analysis HW1RahulSatijaNo ratings yet

- Why Do We Hate Hypocrites - Evidence For A Theory of False SignalingDocument13 pagesWhy Do We Hate Hypocrites - Evidence For A Theory of False SignalingMusic For youNo ratings yet

- AVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDocument16 pagesAVERY, Adoratio PurpuraeDejan MitreaNo ratings yet

- Past Simple (Regular/Irregular Verbs)Document8 pagesPast Simple (Regular/Irregular Verbs)Pavle PopovicNo ratings yet

- CMAR Vs DBBDocument3 pagesCMAR Vs DBBIbrahim BashaNo ratings yet

- "Article Critique" Walden University Methods For Evidence-Based Practice, Nursing 8200 January 28, 2019Document5 pages"Article Critique" Walden University Methods For Evidence-Based Practice, Nursing 8200 January 28, 2019Elonna AnneNo ratings yet

- Creative LeadershipDocument6 pagesCreative LeadershipRaffy Lacsina BerinaNo ratings yet

- Bayonet Charge Vs ExposureDocument2 pagesBayonet Charge Vs ExposureДжейнушка ПаннеллNo ratings yet

- Brand Management Assignment (Project)Document9 pagesBrand Management Assignment (Project)Haider AliNo ratings yet

- Firewatch in The History of Walking SimsDocument5 pagesFirewatch in The History of Walking SimsZarahbeth Claire G. ArcederaNo ratings yet

- SCHEEL, Bernd - Egyptian Metalworking and ToolsDocument36 pagesSCHEEL, Bernd - Egyptian Metalworking and ToolsSamara Dyva86% (7)

- Mcqmate Com Topic 333 Fundamentals of Ethics Set 1Document34 pagesMcqmate Com Topic 333 Fundamentals of Ethics Set 1Veena DeviNo ratings yet