Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Using A Jigsaw Task To Develop Japanese Learners' Oral Communicative Skills: A Teachers' and Students' Perspective

Uploaded by

Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Using A Jigsaw Task To Develop Japanese Learners' Oral Communicative Skills: A Teachers' and Students' Perspective

Uploaded by

Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemCopyright:

Available Formats

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

87

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral

Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

Colin James Thompson and Gareth Andrew Blake

Abstract:

In 2003, the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) issued

a set of guidelines outlining the need to improve Japanese learners use of English. In an attempt to help

meet this objective a Jigsaw task was designed and then implemented into an intermediate level University

EFL program to help develop the oral communication skills of Japanese learners. This paper investigates

how successful the task was in meeting the goals of MEXT and the goals of the program by interviewing

the teachers who used the task in the curriculum. Data was also collected from students who participated

in the task to see how motivational the task was as a means of language learning. The paper begins by

defning tasks and describes how they can be considered a motivational tool for language learning.

The following section describes how a Jigsaw task was chosen and developed to improve learners oral

communication skills in an intermediate level course. The analysis section then describes teachers views

regarding the success of the task in facilitating students use of English as well as meeting the goals of the

course. Student data is also analyzed to determine how motivational the task was. This is followed by the

fndings section which discusses the implications and limitations of these results. The paper concludes

that the Jigsaw task appeared to be a success in meeting the goals of MEXT, it was a suitable task for the

course, and that it was motivational for students however, the results of which are bound by limitations.

Key terms: task, MEXT, curriculum, communication, communicative competence, motivation

Introduction

Recently, the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) has indicated

the need to develop Japanese learners use of English. MEXT was concerned that Japanese students lacked the

necessary English oral skills to communicate effectively in todays global environment. Educational institutions

in Japan began responding to MEXTs goals by developing English curriculums that focused on developing

students oral skills. A study carried out by Millington and Thompson (2009) examined if tasks could be used

as a suitable methodology for developing learners oral interactive skills for an intermediate level program

at Ritsumeikan Asia Pacifc University (APU). The results of the study were successful enough to introduce

tasks into a newly developed intermediate level curriculum that focused on developing learners speaking and

writing skills. In order to design and successfully implement an appropriate task into the course, consideration

would need to be given to make sure the task not only accommodates the goals of MEXT but also the goals

of the course as well as the needs and wants of the students. This paper aims to investigate how successful the

task was in meeting those requirements. This was carried out in two ways. First, six teachers who taught using

the task were interviewed to fnd out how effective the task was in developing learners communication skills.

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

88

Second, the opinions of twenty two students who participated in the task were collected and analyzed to see

how benefcial the task was as a means of oral language learning.

The purpose of this paper is to answer the following questions: How do teachers view a Jigsaw task as

contributing to the development of students use of English in an intermediate level curriculum? How do

teachers view a Jigsaw task as a means to help students meet the speaking goals of the intermediate level

program? How do students consider a Jigsaw task as a motivational means of language learning?

The paper begins by defning tasks and how they can be considered motivational for students learning an L2.

This is followed by a summary of Millington and Thompsons (2009) study that investigated whether tasks

could be used to develop intermediate level learners communicative skills at APU. The paper then discusses

the speaking goals of the intermediate course, the goals of MEXT, and issues relating to learners motivation

towards learning spoken English. The next section outlines the justifcation for choosing a Jigsaw task and how

it was developed to improve learners oral interactive skills. The analysis then describes the teachers views

about how the task facilitated students use of English and how it helped meet the goals of the course, as well as

reporting the student data concerning the motivational aspect of the task. The fndings section then discusses the

limitations and implications of these results. Finally, the paper concludes that the Jigsaw task appeared to be a

success in meeting the goals of MEXT, it was an appropriate task for the curriculum and it was motivational for

the learners but that modifcations could be made to the task to suit the needs of different learners.

Defnition of Tasks

There are many defnitions of pedagogic tasks, however for the purpose of this paper, we shall rely on Bygate,

Skehan and Swains defnition:

A task is an activity which requires learners to use language, with emphasis on meaning, to attain an objective

(2000, p.11)

In other words, tasks are used so learners can communicate with each other in English in order to achieve a non-

linguistic goal. The above defnition differs from the defnition of a task used in Millington and Thompsons

(2009) paper because that task was intended to promote interaction, and elicit correct use of language form by

focusing on the article system. However, the task in this study was primarily intended to promote students use

of English with more emphasis on meaning.

Tasks as a motivational means of language learning

Van Patten (1996) argued that tasks are a motivational way of language learning as they facilitate language use

which is considered to be an enjoyable learning process. In 2000, Littlewood interviewed 2,307 students in

eight East Asian countries about their attitudes towards learning English and his results showed that students

like activities where they are part of a group in which they are all working towards common goalswhen

working in these groups, they all like to help keep the atmosphere friendly (ibid, p. 34). This indicates that

Asian students want to take part in tasks that promote the use of English, and that tasks could be motivational

for them learning an L2.

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

89

Justifcation for using tasks in a University curriculum

The Millington and Thompson (2009) study investigated whether tasks could be used as a methodology in an

intermediate level University program by meeting the communicative goals set out by MEXT (2003). A task

was developed and tested on a class of 24 intermediate level learners and the fndings of the study showed the

task led to improvements in students use of English. Also, as the learners could use whatever language they

felt was necessary, this appeared to motivate their performance, thus supporting Littlewoods (2000) and Van

Pattens (1996) claim that tasks could be a motivational way of language learning. The success of these results

led to the introduction of tasks into a newly developed intermediate level curriculum. However, in order to

design and successfully implement a specifc task into the course program, the task would have to accommodate

the goals of the course as well as the aims of MEXT.

Speaking goals of the curriculum: Communicative competence

The speaking component of the newly developed curriculum was designed on the principles of communicative

competence (Canale and Swain, 1980). Dell Hymes introduced the concept in 1972 and there have been

numerous defnitions of it since. According to Canale and Swain, Hymes original defnition of communicative

competence refers to learners profcient use of an L2 that includes not only grammatical competence (or

implicit and explicit knowledge of the rules of grammar) but also contextual or sociolinguistic competence

(knowledge of the rules of language use) (1980, p.4). In other words, for learners to successfully communicate

in the L2, they need not only the understanding of the grammatical rules, but also the knowledge of how the L2

is used by native speakers in different social contexts.

In order for a curriculum to refect the notion of communicative competence, in particular the sociolinguistic

aspect, it would need to contain a communicative approach towards language learning (Canale and Swain,

1980). As a result, a curriculum would incorporate communicative functions (e.g. apologizing, describing,

inviting, promising) that a given learner or group of learners needs to know and emphasize the ways in which

particular grammatical forms may be used to express these functions appropriately (ibid, p.2). Given the

variety of different social contexts in which English is used, curriculum developers of the program decided to

focus on speaking goals that would allow students to develop the skills to communicate in different situations.

Therefore the goals of giving information and eliciting information seemed appropriate as students could

practice giving information in various ways such as expressing opinions and describing information whilst also

eliciting information by developing the skills of asking questions. Therefore to develop a suitable task for the

program, the task would need to facilitate students use of giving formation and eliciting information.

Aims of MEXT

Another factor infuencing how a task should be used was the communicative goals set out by MEXT. In 2003,

MEXT published guidelines to cultivate students basic and practical communication abilities (Regarding

the Establishment of an Action Plan to Cultivate Japanese with English Abilities, 2003). These guidelines

were issued due to dissatisfaction with Japanese students lack of ability in obtain[ing] and understand[ing]

knowledge and information as well as the abilities to transmit information and to engage in communication. In

order to cultivate these communication abilities, MEXT specifed one main goal for students on graduating from

tertiary education: [o]n graduating from university, graduates can use English in their work. MEXT stated

that in order for students to achieve these goals it is necessary for students to know more than just grammar

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

90

and vocabulary; students also need to have the ability to use English for the purpose of actual communication.

Therefore, in relation to the task chosen for the curriculum, it would need to facilitate learner interaction and

students use of English.

Learner issues related to the aims of MEXT

Designing a task to meet the goals of MEXT however, could still cause problems for certain students. Brown

and Kikuchis (2009) study showed that Japanese students entering University did not appear to have beneftted

from MEXTs guidelines because courses in senior high schools tended to be either entrance examination-

oriented, grammar translation-oriented, or textbook-oriented. Consequently, Japanese students entering

University seem to have had little opportunity to use English through oral communication and may therefore

feel uncomfortable engaging in a communicative task. Greg Ellis (1996) refers to this when the gap between an

old method of instruction and new experience becomes too great, learners produce passive resistance or non-

learning. If the task was designed to meet the communicative goals of the course and MEXT, it may also be

met with resistance from some learners who have not had suffcient exposure with using similar communicative

activities in their previous educational background.

Selection and development of a task for an intermediate curriculum

In order to develop a task that helped to facilitate the goals of the course in giving and eliciting information

whilst also maintaining MEXTs desire for oral communication, it was important to choose the type of task

that would meet these requirements. According to Ellis (2003), task classifcation is important because it

ensures variety on a course by providing teachers with a selection of tasks. It also gives teachers a framework

for experimentation. As with the defnition of tasks, task classifcation has also received much coverage in

the TBLT literature. Ellis summarizes four approaches to classifying tasks: pedagogic; rhetorical; cognitive;

and psycholinguistic. Among these different approaches, Ellis states that the psycholinguistic classifcation of

tasks is based on how students are expected to interact in order to achieve the goals of the task. This allows

opportunities for students to test their language use and work towards comprehension, and by doing so develop

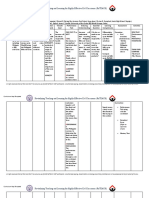

their language ability. Pica et al (1993) proposed the following categories:

1. Interactant relationship (the responsibilities given to task participants to hold, request, and/or supply

information needed to achieve the task goals)

2. Interaction requirement (the optional or obligatory requirements for information to be exchanged by

participants in order to achieve the task goals)

3. Goal orientation (the convergent or divergent requirements of interactants in achieving the goals of the task)

4. Outcome options (the range of acceptable task outcomes available to interactants in attempting to meet task

goals)

Using this framework, Pica et al (1993) devised a typology of communication task types. The following table

identifes the task types and their requirements:

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

91

Interactant

relationship

Interactant

requirement

Goal orientation Outcome options

Jigsaw Each interactant

holds, supplies,

requests

information.

Required Convergent 1

(One outcome

option.)

Information-gap One interactant

holds and supplies

information.

Another requests

information.

Required Convergent 1

(One outcome

option.)

Problem-solving Each interactant

has access to

information and

supplies it if

requested.

Not required Convergent 1

(One outcome

option.)

Decision-making Each interactant

has access to

information and

supplies it if

requested.

Not required Convergent 1+

(More than one

outcome option.)

Opinion-exchange Each interactant

has access to

information and

supplies it if

requested.

Not required Not convergent 1+

More than one

outcome option,

and no outcome

option.

(Pica et al, 1993, p.180)

From the six task types outlined by Pica et al (1993), the curriculum developers felt the Jigsaw task type was

the most conducive to facilitating interaction between students and thus provides opportunities for interactants

to work towards comprehension. Based on the criteria of this type of task, an election task was devised

whereby each student in a group would be given a different profle of a candidate for leader of an English

Circle. Students would need to communicate with each other by describing their candidates profles and asking

questions in order to decide which is the best candidate.

Justifcation for using the Jigsaw Task

The justifcation for using the task was based on three reasons: (1) to meet the speaking goals of the course, (2)

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

92

to meet the guidelines of MEXT, and (3) to be a motivational means of language learning for students.

1. The speaking goals of the course

According to Pica et al (1993), the Jigsaw task type requires each participant to hold, supply and request

information (interactant relationship) to complete the task. This necessitates two-way interaction (interaction

requirement) between participants in order to achieve a convergent (goal orientation), single outcome (outcome

option). Consequently, a jigsaw task is most likely to generate opportunities for interactants to work toward

comprehension, feedback, and interlanguage modifcation processes related to successful SLA (ibid, 1993,

p.175). This type of interaction works well with the speaking goals of the course in giving and eliciting

information. In order to successfully complete the task, students would have to engage in two-way conversation

by giving information, for example, describing their leader profles to the rest of the group. Students would also

work towards comprehension by eliciting information through asking questions to the other group members to

obtain information about the other profles, and then deciding which profle should be elected as leader.

2. Guidelines of MEXT

The guidelines set out in MEXT (2003) for a more communicative approach towards language learning would

appear to match the communicative rationale behind using a Jigsaw task in the classroom. Students would be

required to work together in groups and interact with each other by comparing information in the L2.

3. Motivational means of language learning

The third factor relates to the motivational aspect of the task. As students would have to interact with each other

in the L2 to complete the task, it was intended that they would be motivated by participating in the task and this

would improve their language learning (Van Patten, 1996; Littlewood, 2000; Millington and Thompson, 2009).

However, implications as a result of Brown and Kikuchis (2009) study suggest learners with a lack of exposure

in using the L2 may be resistant to participate in an interactive Jigsaw task.

Methodology

Research objectives

The purpose of this study is to fnd answers to the following questions:

1. How do teachers view a Jigsaw task as contributing to the development of students use of English in an

intermediate level curriculum?

2. How do teachers view a Jigsaw task as a means to help students meet the speaking goals of the intermediate

level program?

3. How do students consider a Jigsaw task as a motivational means of language learning?

Data collection

Part of the data for this research was collected using a qualitative research method by carrying out interviews

with teachers in an attempt to gain detailed objective responses. A quantitative approach was also used to obtain

data from Japanese students of the course in the form of an anonymous questionnaire written in both Japanese

and English. In doing so students could provide information with greater ease and privacy.

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

93

Participants

Six teachers from the intermediate program who used the task in the curriculum during the spring semester

2009 were interviewed. The teachers were of different nationalities Japanese, Scottish, Canadian, Romanian,

American. Twenty-two students of the intermediate level program who completed the task during the Fall 09

semester carried out the anonymous questionnaire.

Interview and Questionnaire Design

The interview data used in this study were taken from nine questions. Most of these are open questions designed

to fnd out how the teachers felt the task contributed towards helping students meet the requirements set out

in MEXT and the speaking goals of the course without asking them directly. The student questionnaire was

comprised of six questions to fnd how Japanese students viewed the task as a motivational means of language

learning. The students were asked to rate each item on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree with the question) to 6

(strongly agree with the question).

The task and how it was used

It was decided that the task would be used as a means of language learning as well as language assessment.

In terms of the former, the task was used following Willis (1996) framework for task-based learning (TBL).

TBL begins with a pre-task stage where the function and goal of the task is introduced to the learners. This

is followed by the task cycle which involves the students doing the task. The fnal part is called language

focus, where learners are given the opportunity to notice the language necessary to successfully complete the

task and can then practice using it by repeating the task. As the task was also later used as a communicative

assessment students were graded on using certain key vocabulary and phrases.

Interview / Questionnaire Settings and Instruments

In order to obtain teachers views on how effective the Jigsaw task was in meeting the goals of the course and

that of MEXT, the interviews were carried out after the semester had fnished, in October 2009. Due to time

constraints, the student data could only be collected at the same time period, at which time the students who

participated in the task during the semester had changed classes. Therefore, the Jigsaw task was carried out

with a new group of intermediate level students. After participating in the task, the students completed the

questionnaire outside of class time via email during November 2009.

Analysis

In terms of how the teachers viewed a Jigsaw task as contributing to the development of students use of

English, the following questions were asked:

1. What do you think the task aims the students to do? / What do think are the main benefts of this task?

2. What are the strengths of the task?

3. How do you think this task makes students interact with one another?

Teacher 1 (T1)

T1 said the task helped students use language to explain their ideas, negotiate to reach a solution and ask other

students questions. The tasks strengths were that it was like a real life situation requiring the use of English and

the students had to interact with each other by asking questions and communicating.

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

94

Teacher 2 (T2)

T2 said the main beneft of the task was that the students were able to use the language that they already had and

to negotiate with each other to make a decision. The task strengths were that it was a group activity so they got

a chance to work together and it was very student centered. Students had to interact by working together and

sharing talking time in order to complete the task.

Teacher 3 (T3)

T3 said the aim of the task was frstly about vocabulary because students had to recognize and defne words,

then they had to compare profles, give arguments, and decide on which profle was best. The task strengths

were that it was easy to follow. In regard to) interaction, T3 said the students had to interact by comparing,

listening and asking questions.

Teacher (T4)

T4 said the task involved students to study and practice new words related to leadership, but that it could also

help students to formulate their opinions. The task strengths were that it provided vocabulary items students had

to use. In response to how students would interact, T4 said that it depends on how the teacher used the task, and

that it could be very interactive.

Teacher (T5)

T5 said the aims of the task were about communication, discussion and exchanging ideas. The task strengths

were that it allowed students to interact naturally with each other using some required vocabulary and the

students could interact by focusing on the goal of the activity whilst the teacher observed.

Teacher (T6)

T6 said the benefts of the task were to practice talking in a group and making decisions, the task strengths

were in allowing students to work in a group, and fnally the task allowed students to interact by expressing

themselves, their ideas and decisions in a group.

From these responses it appears that all the teachers suggest the task contributed to students use of English.

In relation to how teachers viewed a Jigsaw task as a means of meeting the speaking goals of an intermediate

level program (giving information and eliciting information), the following questions were asked:

1. How do you think this task could contribute in terms of students language development?

2. What issues or problems could arise from using this task?

3. Would this task ft in with your teaching?

4. Would you use this task at an intermediate level?

5. Would you change or adapt it?

Teacher 1 (T1)

T1 did not feel that the task was successful in contributing to the students language development because the

students were reluctant to negotiate towards comprehension. Also, students lack of ability in the L2 could cause

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

95

problems for the rest of the group in completing the task. T1 would use the task again and at intermediate level

but would supplement the task by introducing similar mini-tasks beforehand.

Teacher 2 (T2)

T2 felt the task contributed to students language development by giving them confdence to share information

and communicate with each other. The problem of the task could be preventing dominant speakers from

speaking too much and allowing shy learners to participate. T2 would use the task again at intermediate level,

but would like to change the task by repeating it using a different topic.

Teacher 3 (T3)

T3 said the task contributed to students language development by allowing students to use and recycle

vocabulary in different contexts, but was not sure how students could learn new things through the task. The

problem of the task was that if repeated, it would not be much fun for the students and could be too easy. T3

would use the task again at intermediate level, but would change the task in order to allow students to be more

creative, for example with vocabulary use.

Teacher 4 (T4)

T4 said the task contributed to students language development by increasing vocabulary knowledge and use,

and to support their own opinions in English. The problems of the task could relate to Japanese students not

being good at persuading others. T4 would use the task if it could be modifed and would use it at intermediate

level as a warm up, but would change the task depending on the needs of the students and also by allowing them

to use their own vocabulary.

Teacher 5 (T5)

T5 said the task contributed to students language development by learning vocabulary words and then having

natural communication. The task problems could be if students do not support each other or if they do not

prepare for the task by learning the vocabulary. T5 thinks the task is good to have in class but would perhaps

change the task by changing the situation.

Teacher 6 (T6)

T5 said the task contributed to students language development by giving students the opportunity to practice a

discussion using vocabulary. The task problems relate to certain students who may not be able to complete the

requirements of the task or their personal feeling may hinder their performance. T6 was not sure if he would use

the task in his teaching because he had to teach according to the curriculum. However, he would use the task

at intermediate level but would change the task or the preparation for the task depending on the needs of the

students.

These responses show that despite some criticisms of the task, all teachers commented how they would use the

task again in an intermediate level curriculum.

Finally, in terms of how students viewed the task as a motivational means of language learning the following

questions were used:

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

96

1. How enjoyable was this task? 1-6 (6 = a lot of fun)

2. Would you like to do more tasks like this in the classroom? (Yes / No)

3. Do you like speaking to your classmates using English? (Yes / No)

4. How successful do you think you were in completing this task? 1-6 (6= very successful)

5. Do you think this task was suitable for your level? (Yes / No)

6. Have you ever done this kind of task before? (Yes / No)

In terms of enjoyment, 18% of the students chose option four and 64% chose option fve or six (a lot of fun).

68% of the students indicated they would like to continue using similar tasks in their lessons and 100% of

the students liked speaking to their classmates using English. In terms of how successful the students were in

completing the task, 32% chose option fve or six with 50% choosing option four. 77% of the students felt the

task was suitable for their intermediate level and 68% confrmed they had never had this type of task before.

These results show that the majority of students enjoyed using the task and that they would like to use similar

tasks in their lessons. Most of the students also felt the task was suitable for an intermediate level. Therefore

these fndings indicate that the task appears to be a success as a motivational means of language learning despite

only 32% of the students confrming that they were successful in completing the task.

Findings

The purpose of this paper was to investigate whether the implementation of a Jigsaw task into an intermediate

level program was a success in terms of facilitating students use of English, meeting the speaking goals of the

program, and providing a motivational means of language learning for students.

Justifcation for using a Jigsaw task in the curriculum

All the teachers provided comments that the Jigsaw task gave students the opportunity to communicate with

each other using English. Therefore the task appears to be a success in terms of meeting the speaking goals set

out by MEXT. T3 and T4 did refer to the tasks interactive function, however, initially they mentioned the main

aim of the task was vocabulary learning. Although T3 and T4 did not talk in as much detail about the tasks

communicative role as other teachers, they did not have previous experience of using tasks. In fact, only half the

teachers (T1, T2 and T6) had used tasks before in their teaching and so these results indicate a lack of exposure

that teachers may have in regard to task-based teaching. As the student data shows learners are generally

motivated to learn English through using tasks this could prompt the need for more teacher training on the use

of tasks.

In terms of how teachers viewed the Jigsaw task as contributing to the goals of the course, in particular giving

information and eliciting information the results were less clear cut. None of the teachers explicitly referred to

the speaking goals as giving information and eliciting information. However, most of the teachers referred to

students asking questions and giving opinions, and all the teachers said the task was suitable for an intermediate

level. Therefore, it can be implied that the task was a success in meeting the goals for an intermediate

program, although all the teachers gave comments on how they would alter or change the task to either seek

improvements in learners L2 speech or help to meet the needs of different students. For example, T4 would

not have provided any key vocabulary and instead would have allowed students more freedom to engage in

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

97

discussion. T3 would alter the task by allowing the students to be more creative. Although this change may have

the effect of making the task more enjoyable, the interaction requirements would still be the same, and therefore

may still prove challenging for some students. On the other hand, T1, T2 and T6 commented on how they would

introduce some form of pre-task planning before using the Jigsaw task in order to prepare their students to

successfully complete the task. As suggested by T2, this preparation may be in the form of supplementary tasks

whereby the interaction requirements are less demanding, such as problem-solving or decision-making tasks,

and would thus allow lower-level students the opportunity to work towards more interaction when ready. This

may be particularly benefcial for lower-intermediate students who lack the ability to complete the Jigsaw task,

and could help teachers to identify these students needs.

In response to the teachers views, a Jigsaw task may be appropriate for the course in that it facilitates

two-way interaction between learners and thus meets the requirements of MEXT, but in order for it to be a

complete success, there needs to be opportunities for teachers to adapt the task to suit the needs of lower-

level intermediate students. One way in which this can be achieved is by introducing other task-types at the

beginning of the semester, and then building) up towards the Jigsaw task in order to guarantee full interaction of

participants.

Student Questionnaire Results

The majority of the twenty-two students who participated in the questionnaire enjoyed using the task, they

enjoyed speaking to their classmates in English, and they would like to use similar tasks in the future. These

results imply that the task was a success as a motivational way of learning English. However, these results are

bound by the following limitations.

Task limitations

The class was conducted with twenty-two students, and therefore any large classes may not guarantee the same

results as it would be diffcult for the teacher to manage more groups of students. In addition, lower intermediate

levels could also struggle with the language necessary to successfully complete the task. Furthermore, Julkunen

(2001, cited in Dornyei, 2002) comments how learners motivation for using tasks can derive from two sources;

the challenge of the task itself and the intrinsic interest of the language as a whole. Dornyei (ibid.) refers to

these two sources as task-dependent and task independent factors respectively. Consequently, if the students

have a general interest in English, it could be argued that the task, as a motivational means of language learning,

may not be as successful as the results from the questionnaire suggest. For example, students may fnd any

means of English language learning enjoyable, whether it be through tasks or other activities as long as they are

learning English. Dornyei & Kormos (2000, cited in Dornyei, 2002) carried out a study involving two groups of

students performing a task in the L2. One group did not enjoy using the task because they disliked speaking in

the L2. However, when both groups of students performed the task in their L1, the group in question performed

the task with greater interest. This further highlights the diffculties in assessing tasks as a motivational means

of language learning due to various external variables that affect learners motivation. Consequently any results

taken from a task in relation to learners motivation would have reliability issues.

This led us to consider other factors that may alter students motivation when participating in the task. For

example:

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

98

1. Carrying out the task using a different group of students

2. Carrying out the task with students who are friends / not friends

3. Carrying out the task at different times of the day

4. Carrying out the task at different stages of the semester

5. Carrying out the task with different teachers

6. Carrying out the task with lower / higher level intermediate students

Ultimately, as Dornyei points out, Engaging in a certain task activates a number of different levels of related

motivational mindsets and contingencies, resulting in complex interferences (2002, p.374). To accurately

assess learners motivation for language learning would require a much larger scale of investigation taking into

account a multiple of social variables that affect learners behavior in the classroom. In terms of this paper,

although the questionnaire results indicate the task was a motivational form, this cannot be confrmed due to

the many additional variables that infuence learners motivation. Implementing tasks for lower level students

however would require careful planning regarding which task types would be suitable and how teachers would

best facilitate using them in the classroom.

Implications of the Student Questionnaire

The results of the student questionnaire posed a number of implications about how tasks (and subsequent

tasks) could be used in the curriculum in the future. For example, all the students liked speaking English to

their classmates yet only 64% of the students really enjoyed participating in the Jigsaw task. A number of

implications about the task can be drawn based on the remaining students. Although all the students may want

to speak to their classmates in English, this may be in a relaxed, private setting. Whilst having to participate in

a highly interactive task using a variety of speech acts with the additional pressure of having to perform in front

of classmates may not be appealing for some students. Consequently, the use of different task types prescribed

by Pica et al (1993) such as Information Gap or Problem solving tasks which are less interactive may be a

more comfortable form of language learning and hence more motivational. This could result in the use of less

interactive tasks at the beginning of a semester.

Another observation from the student survey was that although 64% really enjoyed using the task and 77%

recommended the task for an intermediate level curriculum, it was surprising that only 32% of the students felt

they were really successful in completing the task, given the fact that 50% of the students voted option four

for successful task completion. This could suggest that students felt they were successful in completing the

task but did not want to appear over-confdent in their L2 ability and were instead modest or shy given their L2

profciency.

After examining the students data, there is support for Van Pattens (1996) and Littlewoods (2000) claims that

by having learners interact with each other using English this will serve to motivate their language learning. For

example, a lot of students commented that they enjoyed speaking to their classmates in English, they enjoyed

the task, they felt they completed it successfully and they would like to learn English by using more tasks in the

future. However, other students responded differently. For example, one student did not enjoy the task and had

repeated this type of task before. Therefore this learners motivation may be attributed to the fact that the learner

did not fnd the task challenging or interesting because they had repeated the task. This refects T3s comments

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

99

that repeating the same type of task may result in learners losing interest. Another student did not enjoy the task,

was not successful in completing the task and had not used this kind of task before, but still recommended using

the task in an intermediate course. From this it could be assumed that certain students may lack the confdence

or ability to speak in the L2. The consequence of this could be to incorporate a variety of different tasks into the

curriculum each involving different challenges thus maintaining learners interest. However, the tasks would

have to be structured in a way that each task follows on from the last so as to gradually develop the learners

oral L2 ability, for example, starting with a less interactive task and fnishing with a highly interactive task such

as the Jigsaw task.

Conclusion

This study investigated how a Jigsaw task that was incorporated into an intermediate level University

curriculum was considered a success in relation to three factors: MEXTs desire for Japanese learners to

improve their use of English, the speaking goals of the course, and as a motivational form of language learning.

To determine this, interviews were carried out with the teachers who used the task and data was also collected

from students who participated in the task. The fndings of our investigation confrm that all the teachers viewed

the Jigsaw task as contributing towards students use of English. Therefore the task appeared to be a success in

helping to meet the communicative goals set out in MEXT. In terms of the task meeting the speaking goals of

the course, the teachers did not refer explicitly to the goals of the course, however, all the teachers confrmed

that the task was a success in terms of sharing information and asking questions which can be interpreted

as giving information and eliciting information. A further indication of the tasks suitability was that all the

teachers would use the task in an intermediate level curriculum. Finally, the fndings from the student data

showed the task seems to be a success as a motivational means of language learning. The majority of the

students enjoyed participating in the task and would like to participate in similar tasks in the future. However,

there are a number of limitations regarding the student data, for example, only twenty-two students participated

in the task questionnaire, and therefore any implications from this study can only be speculative. Also, as

motivation is such a complex issue involving so many variables it makes it diffcult to reach any accurate

conclusions.

Overall our results are positive enough to continue using tasks in the curriculum. The implications from this

study suggest the task could be changed to suit the needs and wants of different learners. One area relates to the

highly interactive nature of the Jigsaw task which could pose diffculties for lower-intermediate level students.

This could result in the introduction of other task types at the beginning of the curriculum which require less

interaction and instead could help scaffold the communicative skills of students during the semester until they

reach the stage where they can successfully complete a Jigsaw task and know that they are heading towards

communicative competence.

References

Browne, C. & Kikuchi, K. (2009). English education policy for high schools in Japan: ideals vs. reality, RELC

Journal, 40: 172-191.

Bygate, M., Skehan, P. & Swain, M. (2000). Researching Pedagogic tasks: second language learning, teaching,

testing. New York: Longman

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

100

Canale, M. & Swain, M. (1980) Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching

and testing, Applied Linguistics, 1:1-47.

Dornyei, Z. (2002) The motivational basis of language learning tasks. In Van den Branden, K., Bygate, M., & J.

M. Norris (Eds), Task-based language teaching (pp.171-192).

Dornyei, Z. & Kormos, J. (2000). The role of individual and social variables in oral task performance.

Language Teaching Research, 4, 275-300.

Ellis, G. (1996). How culturally appropriate is the communicative approach? ELT Journal, 50/3: 213-218.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Julkunen, K. (2001). Situational-and task-specifc motivation in foreign language learning. In Z. Dornyei &

R. Schmidt (Eds.), Motivation and second language acquisition (pp. 29-41). Honolulu, HI: University of

Hawaii Press.

Littlewood, W. (2000). Do Asian students really want to listen and obey? ELT Journal, 54/1: 31-35.

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) (2003). Regarding the Establishment

of an Action Plan to Cultivate Japanese with English Abilities. Retrieved from http://www.mext.go.jp/

english/topics/03072801.htm

Pica, T., Kanagy, R. & Falodun, J. (1993). Choosing and using communication tasks for second language

instruction. In Van den Branden, K., Bygate, M., & J. M. Norris (Eds), Task-based language teaching

(pp.171-192).

VanPatten, B. (1996). Input processing and grammar instruction. Norwood, N.J: Ablex.

Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based langugae teaching. New York: Longman.

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

101

Appendix

Task materials

Cut these apart. Give one to each student. Write the eight characteristics on the board. Students should share

their profles with the group, and discuss what characteristics each leader has. Finally, each group should elect

the person that they think is best qualifed for the role of leader.

8 characteristics of leaders:

0. Vision

1. Persuasiveness

2. Good at deal-making

3. Tenacity

4. Team-worker

5. Confdent

6. Popular

7. Fluent in English

NAME: Bill AGE: 21

I want to create an English Circle where students can study English online anytime, with their own

computer and brand new computer programs.

Characteristic:

I don't have many friends, because I spend a lot of time playing with computers, and last year started a

computer company at university.

Characteristic:

NAME: Shunsuke AGE: 18

I am a member of the soccer club at university. We have 32 members, and we do everything together, as a

team. If one of the members is in trouble, we help him or her, and they all help me.

Characteristic:

Last year, I was chosen Best Player in the universitys soccer team by my team-mates. This made me

really happy, because two years ago I broke my leg, and the doctor said I would never play soccer again. I

practiced and practiced and trained and trained, and now I am a great player.

Characteristic:

Polyglossia Vol. 18, February 2010

102

NAME: Jerry AGE: 20

I was born and raised in America, and came to Japan last year to study at university.

Characteristic:

I watch a lot of TV, and I think watching TV makes learning languages easier. I want to get giant plasma

TVs in every room and on every wall of the universitys buildings, all showing English movies and TV

programs.

Characteristic:

NAME: Ayu AGE: 17

I love singing. I go to karaoke 4 times a week with my friends, and I have hundreds of friends.

Characteristic:

Some people say singing in front of lots of people is scary, but I think it is the best feeling in the world. I I

have a pretty good voice and I can sing, and talk, in front of anybody.

Characteristic:

NAME: Johnny AGE: 19

Last year, I started a Movie Club with 5 friends, and we all share the work. When I am busy, my friends do

extra work, and when they are busy, I work harder.

Characteristic:

Last year I had a 2hour meeting with the offce staff at APU, and we made a deal to show English movies

every night at APU, for free.

Characteristic:

NAME: Kimberly Age: 22

I worked with some of my friends to open a dance club at university. Every Friday we get DJs from a

famous club in Beppu to come to the university and play dance music for free. In exchange, every Saturday

night we go to the club to help serve food and drinks.

Characteristic:

At frst, no one came to our night club, but we didnt give up. We changed the music and added some

decorations and now the club is full every Friday night!

Characteristic:

Using a Jigsaw Task to Develop Japanese Learners Oral Communicative Skills: A teachers and students perspective

103

NAME: Johnny AGE: 19

Characteristic:

At frst, no one came to our night club, but we didnt give up. We changed the music and added some

decorations and now the club is full every Friday night!

Characteristic:

You might also like

- The Structured Method of Pedagogy: Effective Teaching in the Era of the New Mission for Public Education in the United StatesFrom EverandThe Structured Method of Pedagogy: Effective Teaching in the Era of the New Mission for Public Education in the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Distributed Leadership in Organizations - Review of Theory and Research - IJMR.2011Document19 pagesDistributed Leadership in Organizations - Review of Theory and Research - IJMR.2011johnalis22No ratings yet

- Macro and Micro Evaluation of Task Based TeachingDocument47 pagesMacro and Micro Evaluation of Task Based Teachingsteadyfalcon100% (2)

- Denver School-Based Restorative Practices Partnership: Implementation GuideDocument44 pagesDenver School-Based Restorative Practices Partnership: Implementation GuideMichael_Lee_Roberts100% (2)

- Research PresentationDocument14 pagesResearch PresentationCeeNo ratings yet

- CaseStudy MindanaoStateUniversityDocument9 pagesCaseStudy MindanaoStateUniversityJessa Mae Banse LimosneroNo ratings yet

- Leveraging Leaders: A Literature Review and Future Lines of Inquiry For Empowering Leadership ResearchDocument45 pagesLeveraging Leaders: A Literature Review and Future Lines of Inquiry For Empowering Leadership ResearchMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Leveraging Leaders: A Literature Review and Future Lines of Inquiry For Empowering Leadership ResearchDocument45 pagesLeveraging Leaders: A Literature Review and Future Lines of Inquiry For Empowering Leadership ResearchMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Module 3 Task 1Document3 pagesUnit 3 Module 3 Task 1Aslı Serap Taşdelen100% (1)

- The Use of Task-Based Learning Activity: A Study On The Three Narrative Components As Seen in The Senior High School Reflective EssaysDocument26 pagesThe Use of Task-Based Learning Activity: A Study On The Three Narrative Components As Seen in The Senior High School Reflective EssaysJoneth Derilo-VibarNo ratings yet

- Digital Technologies in Education 4.0-Does It Enhance The Effectiveness of LearningDocument17 pagesDigital Technologies in Education 4.0-Does It Enhance The Effectiveness of LearningMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- The Strengths and Weaknesses of Task Based Learning (TBL) Approach.Document12 pagesThe Strengths and Weaknesses of Task Based Learning (TBL) Approach.Anonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Improving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic JournalDocument11 pagesImproving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic JournalViophiLightGutNo ratings yet

- Proposal Action ResearchDocument31 pagesProposal Action ResearchSanuri Oke63% (8)

- Practicum Evaluation Form: NA Not ApplicableDocument1 pagePracticum Evaluation Form: NA Not ApplicableCOLEGIO DE SANTIAGO APOSTOL, INC. Plaridel BulacanNo ratings yet

- Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Francisco Morazán: Class: TESOL WorkshopDocument57 pagesUniversidad Pedagógica Nacional Francisco Morazán: Class: TESOL WorkshopJose Miterran Hernandez MunguiaNo ratings yet

- ALIGUAY First Reflection EDL 251Document10 pagesALIGUAY First Reflection EDL 251FrankieNo ratings yet

- Focus of Research-Team08Document7 pagesFocus of Research-Team08Miranda BustosNo ratings yet

- 224 425 1 SMDocument8 pages224 425 1 SMfebbyNo ratings yet

- The Application of Interactive Task-Based Learning For EFL StudentsDocument9 pagesThe Application of Interactive Task-Based Learning For EFL StudentsAhmed Ra'efNo ratings yet

- Fitriani He PaperDocument11 pagesFitriani He PaperFitrianiNo ratings yet

- Mid Term AsignmentDocument10 pagesMid Term AsignmentWinda DNo ratings yet

- Using The Mind Mapping Technique For Better Teaching of Writing in English by FitriaDocument13 pagesUsing The Mind Mapping Technique For Better Teaching of Writing in English by FitriaLEMAR LUMBANRAJANo ratings yet

- The Implementation of Cooperative Script Technique in Teaching Reading Comprehension To The Students of Senior High SchoolDocument12 pagesThe Implementation of Cooperative Script Technique in Teaching Reading Comprehension To The Students of Senior High SchoolAzida KhairaniNo ratings yet

- 7259 19724 1 PBDocument8 pages7259 19724 1 PBRaghadNo ratings yet

- Teaching Grammar Through Task-Based Language Teaching To Young EFL LearnersDocument15 pagesTeaching Grammar Through Task-Based Language Teaching To Young EFL Learnersminoucha manouNo ratings yet

- Use of Picture As TestDocument15 pagesUse of Picture As TestAnonymous 18wd39bNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis Team8Document9 pagesData Analysis Team8Miranda BustosNo ratings yet

- 10 55078-Lantec 1118527-2435881Document13 pages10 55078-Lantec 1118527-2435881Ahmet Gökhan BiçerNo ratings yet

- 2015 Theme Based Curriculum and Research Based InstructionDocument21 pages2015 Theme Based Curriculum and Research Based InstructionFong King YapNo ratings yet

- JURNAL BAHASA INGGRIS SemiinarDocument8 pagesJURNAL BAHASA INGGRIS SemiinarLimaTigaNo ratings yet

- Influence of Implementing RT in L2 Classes Reading Skills & Motivation To Read Qutob 2020 Has QuestionnaireDocument13 pagesInfluence of Implementing RT in L2 Classes Reading Skills & Motivation To Read Qutob 2020 Has QuestionnaireAqila HafeezNo ratings yet

- The Application of Peer-Assisted Study Sessions (Pass) To Teach Writing at Students of Class Eight of SMP Negeri Sempol BondowosoDocument11 pagesThe Application of Peer-Assisted Study Sessions (Pass) To Teach Writing at Students of Class Eight of SMP Negeri Sempol BondowosoAndry Sartika, S.Kep.,Ners.,M.KepNo ratings yet

- "Improving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic": AbstractDocument10 pages"Improving Vocabulary Ability by Using Comic": AbstractekanailaNo ratings yet

- Karil Sastra InggrisDocument12 pagesKaril Sastra InggrisyasiriadyNo ratings yet

- Teacher's Code-Switching As Scaffolding in Teaching Content Area SubjectsDocument5 pagesTeacher's Code-Switching As Scaffolding in Teaching Content Area SubjectsJessemar Solante Jaron WaoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 EditedDocument7 pagesChapter 1 EditedRosevee Cerado HernandezNo ratings yet

- AsiaTEFL V4 N4 Winter 2007 Developing Learners Oral Communicative Language Abilities A Collaborative Action Research Project in ArgentinaDocument27 pagesAsiaTEFL V4 N4 Winter 2007 Developing Learners Oral Communicative Language Abilities A Collaborative Action Research Project in ArgentinaFrank RamírezNo ratings yet

- Theories in Developing Oral Communication For Specific Learner Group Marham Jupri HadiDocument6 pagesTheories in Developing Oral Communication For Specific Learner Group Marham Jupri Hadivaughn jayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document14 pagesChapter 2Hamzah FansyuriNo ratings yet

- 90-Article Text-239-2-10-20200310Document7 pages90-Article Text-239-2-10-20200310nanik lestariNo ratings yet

- Project-Based Learning and Problem-Based Learning For EFL Students' Writing Achievement at The Tertiary LevelDocument18 pagesProject-Based Learning and Problem-Based Learning For EFL Students' Writing Achievement at The Tertiary LevelIla Ilhami QoriNo ratings yet

- Ewc ProposalDocument7 pagesEwc ProposalIkhmal AlifNo ratings yet

- Thesis Proposal 0.2 MayangDocument31 pagesThesis Proposal 0.2 MayangMayang jinggaNo ratings yet

- Task 2Document5 pagesTask 2api-302673693No ratings yet

- Learning by Teaching, Teach English As A Second Language Learning Method in MexicoDocument6 pagesLearning by Teaching, Teach English As A Second Language Learning Method in MexicoMd Salah Uddin RajibNo ratings yet

- The Use of Crossword Puzzle To Improve VocabularyDocument10 pagesThe Use of Crossword Puzzle To Improve VocabularyVina MustikaNo ratings yet

- Def& Types of Task BassedDocument17 pagesDef& Types of Task BassedNgọc PhươngNo ratings yet

- Bismillah Proposal AisyahDocument16 pagesBismillah Proposal AisyahMuhammad Riezal DkbpNo ratings yet

- Speaking-1 Ka Ofi, Monic, j2nDocument8 pagesSpeaking-1 Ka Ofi, Monic, j2nMuhamad jejen NuraniNo ratings yet

- As The Author KhanDocument12 pagesAs The Author KhanCamilo Bonilla TorresNo ratings yet

- Reaction PaperDocument9 pagesReaction PaperMelchor Sumaylo PragaNo ratings yet

- Task Based Learning Factors For Communication and Grammar UseDocument9 pagesTask Based Learning Factors For Communication and Grammar UseThanh LêNo ratings yet

- Ped Gram Final OutputDocument8 pagesPed Gram Final Outputamara de guzmanNo ratings yet

- Bab 2 by EnglishDocument18 pagesBab 2 by EnglishM.Nawwaf Al-HafidzNo ratings yet

- Caluna Action Research Cpnhs 2021Document19 pagesCaluna Action Research Cpnhs 2021Earl Vestidas CapurasNo ratings yet

- Benefits and Implementation Challenges of Task-Based Language Teaching in The Chinese EFL ContextDocument8 pagesBenefits and Implementation Challenges of Task-Based Language Teaching in The Chinese EFL ContextNgọc Điệp ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Findings Final LTMDocument25 pagesFindings Final LTMLee LeeNo ratings yet

- 1659-ArticleText-3880-1-10-20180122Document9 pages1659-ArticleText-3880-1-10-20180122Gomez Al MuhammadNo ratings yet

- A. Research BackgroundDocument26 pagesA. Research BackgroundPutriFiraNurulHanifahNo ratings yet

- A Study of the Effectiveness of Dictogloss on English Grammar and Motivation for Japanese Junior College Students in English Communication Class 英文法指導におけるディクトグロスの有効性とモチベーションに関する一考察Document12 pagesA Study of the Effectiveness of Dictogloss on English Grammar and Motivation for Japanese Junior College Students in English Communication Class 英文法指導におけるディクトグロスの有効性とモチベーションに関する一考察Nguyen HalohaloNo ratings yet

- Project Based Learning IndonesiaDocument16 pagesProject Based Learning Indonesiagabriela.carroNo ratings yet

- Task Based LearningDocument4 pagesTask Based LearningBambang SasonoNo ratings yet

- Admin,+5 Nengah+Dwi+HandayaniDocument5 pagesAdmin,+5 Nengah+Dwi+HandayaniWandaNo ratings yet

- Project Work For Teaching English For Esp Learners.: Pham Duc ThuanDocument16 pagesProject Work For Teaching English For Esp Learners.: Pham Duc ThuanRodica Stanislav CiopragaNo ratings yet

- Improving Students' Achievement in Writing Descriptive Paragraph Through Simultaneous Roundtble Strategy Yudhi Pratama Tarigan Yunita Agnes SianiparDocument16 pagesImproving Students' Achievement in Writing Descriptive Paragraph Through Simultaneous Roundtble Strategy Yudhi Pratama Tarigan Yunita Agnes SianiparJo Xin Tsaow LeeNo ratings yet

- Proposal QRMDocument8 pagesProposal QRMWira AgustyanNo ratings yet

- CTL Excerpt WeeblyDocument15 pagesCTL Excerpt Weeblyapi-518405423No ratings yet

- Transformation or Evolution Education 4 0 Teaching and Learning in The Digital AgeDocument25 pagesTransformation or Evolution Education 4 0 Teaching and Learning in The Digital AgewilsonNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1048984317300607 MainDocument25 pages1 s2.0 S1048984317300607 MainRizky AmeliaNo ratings yet

- Linking Empowering Leadership and Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship BehaviorDocument20 pagesLinking Empowering Leadership and Change-Oriented Organizational Citizenship BehaviorMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Ethical and Empowering Leadership and Leader EffectivenessDocument15 pagesEthical and Empowering Leadership and Leader EffectivenessMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- The Leadership Quarterly: Robert P. Vecchio, Joseph E. Justin, Craig L. PearceDocument13 pagesThe Leadership Quarterly: Robert P. Vecchio, Joseph E. Justin, Craig L. PearceMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 2014 3Document67 pages2014 3Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 2013Document27 pages2013Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- The Empowering Leadership Questionnaire: The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader BehaviorsDocument23 pagesThe Empowering Leadership Questionnaire: The Construction and Validation of A New Scale For Measuring Leader BehaviorsMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Leadership For Community Engagement-A Distributed Leadership PerspectiveDocument30 pagesLeadership For Community Engagement-A Distributed Leadership PerspectiveMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Incremental Validity of The Distributed Leadership Scale: Pai-Lu Wu, Hui-Ju Wu, Pei-Chen WuDocument14 pagesIncremental Validity of The Distributed Leadership Scale: Pai-Lu Wu, Hui-Ju Wu, Pei-Chen WuMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Gunter AdabDocument23 pagesGunter Adabscholar786No ratings yet

- Through An Eastern Window Muslims in CoDocument14 pagesThrough An Eastern Window Muslims in CoMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Increasing Behavioral Skills and Level of Understanding in Adults: A Brief Method Integrating Dennison's Brain Gym Balance With Piaget's Reflective ProcessesDocument17 pagesIncreasing Behavioral Skills and Level of Understanding in Adults: A Brief Method Integrating Dennison's Brain Gym Balance With Piaget's Reflective ProcessesMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 2016Document8 pages2016Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Incremental Validity of The Distributed Leadership Scale: Pai-Lu Wu, Hui-Ju Wu, Pei-Chen WuDocument14 pagesIncremental Validity of The Distributed Leadership Scale: Pai-Lu Wu, Hui-Ju Wu, Pei-Chen WuMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 2017Document22 pages2017Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 2004 1Document179 pages2004 1Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Movement in The Special Education Classroom The Effectiveness of Brain Gym® Activities On Reading AbilitiesDocument65 pagesMovement in The Special Education Classroom The Effectiveness of Brain Gym® Activities On Reading AbilitiesMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- PlesDocument13 pagesPlesMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 4-Brain Gym®Document13 pages4-Brain Gym®Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Moore, H., & Hibbert, F. (2005) - Mind Boggling! Considering The Possibilities of Brain Gym in Learning To Play An Instrument. British Journal of Music Education, 22 (3), 249-267.Document20 pagesMoore, H., & Hibbert, F. (2005) - Mind Boggling! Considering The Possibilities of Brain Gym in Learning To Play An Instrument. British Journal of Music Education, 22 (3), 249-267.Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- Using Augmented Reality in Early Art Education: A Case Study in Hong Kong KindergartenDocument16 pagesUsing Augmented Reality in Early Art Education: A Case Study in Hong Kong KindergartenMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 10.1007/978 94 007 6321 0 - 2Document14 pages10.1007/978 94 007 6321 0 - 2Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 2 2016Document4 pages2 2016Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- PlesDocument13 pagesPlesMohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- 2 2016Document4 pages2 2016Mohammed Mohammed Shoukry NaiemNo ratings yet

- FEES SCH3U Course OutlineDocument1 pageFEES SCH3U Course OutlineFESSCHEMNo ratings yet

- Unit 11: Develop Professional Supervision Practice in Health and Social Care or Children and Young People's Work SettingsDocument4 pagesUnit 11: Develop Professional Supervision Practice in Health and Social Care or Children and Young People's Work SettingsMalgorzata MarcinkowskaNo ratings yet

- Developing Reading ActivitiesDocument3 pagesDeveloping Reading ActivitiesbaewonNo ratings yet

- DLL EIM G9 - 3rd Grading Week 1Document4 pagesDLL EIM G9 - 3rd Grading Week 1Bong Carey100% (1)

- Steven TDocument1 pageSteven Tapi-311102929No ratings yet

- BTPDocument2 pagesBTPakashkadalisriNo ratings yet

- 2022-23 SSO Calendar SummerSchoolOnlineDocument2 pages2022-23 SSO Calendar SummerSchoolOnlineRobert CNo ratings yet

- Report Part 1Document7 pagesReport Part 1Seth NurulNo ratings yet

- Academic Calendar Spring 2022Document1 pageAcademic Calendar Spring 2022MAHABUBUL ISLAM NAYEMNo ratings yet

- Objectives of Training and DevelopmentDocument9 pagesObjectives of Training and DevelopmentRaksha Shukla0% (1)

- 19 Intl JChild Rts 547Document25 pages19 Intl JChild Rts 547Aslı AlkışNo ratings yet

- (FINAL) Social Institutions-Education, Government, EconomyDocument17 pages(FINAL) Social Institutions-Education, Government, EconomyMariel Paz MartinoNo ratings yet

- Prospectus: Under Graduate ProgrammesDocument30 pagesProspectus: Under Graduate ProgrammesSid SimpsonNo ratings yet

- Strategies in Science of ReadingDocument16 pagesStrategies in Science of ReadingMJEtreufallivNo ratings yet

- Supporting DetailsDocument3 pagesSupporting Detailsapi-301607600No ratings yet

- Tutoring Plan Template 1Document12 pagesTutoring Plan Template 1api-370205219No ratings yet

- College Affordability Final ReportDocument32 pagesCollege Affordability Final ReportAndi ParkinsonNo ratings yet

- Formal-Analysis-Writing-Rubric Spivey1Document1 pageFormal-Analysis-Writing-Rubric Spivey1api-310912859No ratings yet

- Unit Lesson 4 - Community HelpersDocument2 pagesUnit Lesson 4 - Community Helpersapi-354551047100% (1)

- The Variance Competence ModelDocument2 pagesThe Variance Competence ModelNanda Nazzha MeilaniNo ratings yet

- Oxford University Guide 2012Document191 pagesOxford University Guide 2012Geronimo StiltonNo ratings yet

- 4th Grade Narrative Story Writing RubricDocument3 pages4th Grade Narrative Story Writing RubricVilla Vanessa Mae R.No ratings yet

- Bridgeport CT Adopted Budget 2008-2009Document516 pagesBridgeport CT Adopted Budget 2008-2009BridgeportCTNo ratings yet

- Cmap Math A PentasticsDocument10 pagesCmap Math A PentasticsMirasol BaringNo ratings yet

- Organization and Management of Sports EventsDocument4 pagesOrganization and Management of Sports Eventsarianeanonymous1No ratings yet