Professional Documents

Culture Documents

John Ashton Oslo Speech August 2014

John Ashton Oslo Speech August 2014

Uploaded by

climatehomescribd0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

433 views25 pagesThis document is a speech given by John Ashton at the Statkraft Conference in Lysaker, Oslo on August 21, 2014. In the speech, he recalls fond childhood memories from a summer vacation in Norway in 1968. He discusses how Norway had achieved near utopian prosperity and social welfare in the postwar years. However, he expresses concern that global challenges may threaten what Norway has built, so Norway must reaffirm its values and develop a vision for navigating future challenges through responsibility and sacrifice.

Original Description:

John Ashton speech

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document is a speech given by John Ashton at the Statkraft Conference in Lysaker, Oslo on August 21, 2014. In the speech, he recalls fond childhood memories from a summer vacation in Norway in 1968. He discusses how Norway had achieved near utopian prosperity and social welfare in the postwar years. However, he expresses concern that global challenges may threaten what Norway has built, so Norway must reaffirm its values and develop a vision for navigating future challenges through responsibility and sacrifice.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

433 views25 pagesJohn Ashton Oslo Speech August 2014

John Ashton Oslo Speech August 2014

Uploaded by

climatehomescribdThis document is a speech given by John Ashton at the Statkraft Conference in Lysaker, Oslo on August 21, 2014. In the speech, he recalls fond childhood memories from a summer vacation in Norway in 1968. He discusses how Norway had achieved near utopian prosperity and social welfare in the postwar years. However, he expresses concern that global challenges may threaten what Norway has built, so Norway must reaffirm its values and develop a vision for navigating future challenges through responsibility and sacrifice.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 25

The Statkraft Conference

Lysaker, Oslo, 21 August 2014

Speech by John Ashton

Little Norway, Big Norway

Electricity Today and Tomorrow: Reflections on

Europe, Energy and Climate Change

1. All Norway basked that August in perpetual

sunshine. Or so it seemed to one wide-eyed

visitor from England, on vacation with his family

in the old whaling town of Sandefjord.

2. Still in the fullness of childhood, eleven years old.

Every day on the beach, in the water, swimming,

splashing, shouting. Look at me.

3. He and his three siblings were a handful, and his

parents were grateful for the support of Signe,

their young Norwegian au pair, who went

everywhere with the family. And in Sandefjord

she was joined by her big sister Solveig.

4. Signe: sweet-natured and warm. Solveig:

willowy, graceful, cool. Apple pie and ice cream.

Both always ready with a reassuring smile, ready

to throw back the beach ball, to laugh at his

jokes, and to laugh with him as he did his best to

master their exotic language. Jeg liker is. Jeg

liker eplepai.

5. Signe and Solveig were angels and that summer

was a Norwegian idyll. The man the boy grew up

to be can still hear the laughter on the beach,

echoing down a corridor nearly five decades long.

6. Yet somehow he began in those weeks to sense

that he would soon enter a more complicated

world, a world of shadow as well as light, of the

unexpected as well as the familiar, of feelings

and events that could take you unawares.

7. One day in the warm shallow waters he noticed

some strange pink blobs. And then he heard

something he had never heard before. He heard

his mother scream. Brenn maneter, one bit of

Norwegian vocabulary he has never forgotten.

The pink blobs were jellyfish and one of them had

stung her.

8. Terror as he scrambled out of the water was

quickly displaced by rage at his normally gentle

father who, with a thirst for vengeance worthy of

Odin himself, promptly executed the aquatic

criminal by burying it in sand. It has a right to

live, protested the son in vain, not really

understanding why he was so upset.

9. He learned a grown up lesson that day. The

water may look inviting. But it is not always safe

to go into it.

10. That summer happened to be a momentous

one. It was 1968. As jellyfish invaded a

Sandefjord beach, Russian tanks were rolling into

Wenceslas Square, bringing the curtain brutally

down on the Prague Spring. The news as it came

through burst the warm holiday bubble that had

enveloped the boys family. It was not so much

the tanks he found unsettling as the shadow that

fell across the faces of his parents, and even of

Signe and Solveig, normally ever cheerful.

11. And with that came a second grown up lesson.

Contentment always exists in a bubble. The

outside world is never far away and events there

can prick the bubble with no warning.

12. Why after all did the Gods need to build a wall

with turrets and sentinels behind which to disport

themselves? Outside, their old enemies pace the

bounds, waiting for a breach. Eventually the wall

proves useless, the enemy swarms in, the Gods

of the old order resist valiantly but they know they

must perish. Asgard always falls and something

new must take its place.

13. Soon afterwards Signe left to build her own life.

Devoted as he had become to the two sisters, the

wide-eyed English boy never saw Signe or

Solveig again.

14. I am the man the boy grew up to be, today

once again back in Norway in August, and I

cannot quite suppress an impossible hope that

Signe and Solveig are sitting somewhere here in

this hall.

15. Anyway, Sandefjord in 1968 may have been

my first experience of Norway, but I was really

only continuing a family tradition.

16. My grandparents - my mothers parents - lived

in a large house, Windrush, surrounded by a

garden full of apple trees, daisies and buttercups,

badgers, foxes and owls. This corner of

wonderland was located in Boars Hill, outside

Oxford, where my grandfather was Professor of

Forestry at the University.

17. The guest bedroom in Windrush was always

known in their household as Little Norway. That

was because, during the War, they had kept open

house for Norwegian airmen who had escaped to

Britain ahead of the German invasion, and who

now flew alongside their Royal Air Force

comrades, in the celebrated free Norwegian

fighter squadrons, the 331

st

and 332

nd

.

18. In Boars Hill these brave men could enjoy a

well-deserved respite from the Luftwaffe, amidst

leafy tranquility, home cooking, and bracing

Oxonian discourse.

19. Follow the branches further back and they join

in a single Anglo-Norwegian trunk. I only

discovered this from my mother as I was

preparing for this visit, but her mother was cousin

to a shipwright from Larvik, a stones throw from

Sandefjord, whose name will be well known to

you.

20. He was Colin Archer, who built the Fram, that

sailed to one end of the Earth with Nansen and

with Amundsen to the other, and now in stately

retirement welcomes visitors not far from here in

its own museum. I went there this morning. The

reek of tar and pine and varnish, and of

adventure, is still overpowering. I have to say I

felt proud as I contemplated the handiwork of my

great Norwegian forebear.

21. Its a small world and in it there are bonds of

history, respect and affection that tie my nation

and yours together. Thats why, though I am a

visitor here, I feel I can only do honour to your

invitation if I speak to you like this, from my heart.

[PAUSE]

22. Since those days when our airmen flew side-

by-side to keep our continent free, what you have

accomplished in this land is little short of

miraculous.

23. I dont want to sound starry-eyed or envious.

There are certainly no Utopias on Earth nor ever

will be.

24. But if Utopia were a realm that is safe and

fruitful, where everybody has enough; a realm

where what binds people together is stronger

than what pits them against each other, where

those who prosper yield up freely a portion of

what they gather to help those less fortunate; a

realm where in times of bounty there is the

foresight to put something away for when the wolf

is scratching at the door; and where from

childhood you can look forward to a life that will

be long, healthy, and if you are not too

melancholy happy as well: if Utopia were all

those things then in Norway in these postwar

years you came pretty close to it.

25. Yes, I did say came. The choice of tense was

deliberate. Some of you, I know, can just hear a

naggle rattle in the distance. Will Norway

tomorrow really be quite such a nice place as it is

today? Have you already passed your peak or if

not, will you have to strive harder to hold onto

what you have?

26. That is a widespread fear. It is spreading

across the industrialized world, in all those

countries that have enjoyed relative peace and

prosperity since World War II, and even beyond

to those reaching for it now. In many such places,

including in Britain, anxiety about tomorrow

weighs a lot heavier than it yet does here,

particularly on young people.

27. And there is a good reason for the anxiety.

Outside the wall, old enemies prowl with new

vigour. Poverty and conflict. Discontent,

displacement, and disorder. They have always

been there but we sense this time that they are

driven by deeper forces than we have seen in our

lifetimes: historic forces, unleashed by our own

unquenchable desires, and acting now on a

global scale.

28. If we fail to make the effort to understand those

forces, to summon the will and wisdom to tame

them, they will sweep aside everything we value.

[PAUSE]

29. When what you have built is under threat, you

must first remind yourself of the virtues that

enabled you to build it.

30. Shared values are the bedrock of any nation.

Your values - your independence of spirit, your

love of freedom and of your rugged land, your

commitment to each other - were forged in your

successful struggles to make yourselves a free

people.

31. And when on 22 July 2011 thunderbolts

smashed down from a clear sky onto Oslo and

Utya, and cut short the lives of 77 Norwegians,

your first instinct was not to lash out, it was to

reaffirm the values that make you who are.

32. Even before you knew that there was no further

threat, you made clear that no corners would be

cut, no suspects secretly rounded up and

tortured, no laws suspended. Standing on the

shoulders of those who came before you, you

knew immediately that the rights they fought and

sometimes died to win must under no

circumstances be compromised.

33. You also knew that the goal of politically

motivated violence in peacetime is not the

shedding of blood. It is by shedding blood to

provoke repression, because a nation that

betrays its own values is a weakened nation.

34. Please know that many of us in Britain, sharing

your grief, applaud too the dignity and clarity of

mind with which you acted.

35. But values alone are not enough.

36. A nation needs a vision. Where there is no

vision, the people perish as it is written in the

Book of Proverbs.

37. Thats a question not just of who you are but of

what kind of society you choose to build. If you

have a vision, the future isnt whatever is going to

happen to you. It is something you make, you

take responsibility for making, even if struggle

and sacrifice are going to be needed.

38. And it seems to me this taking of responsibility

for the future is also a Norwegian virtue.

39. When oil and gas were found under the North

Sea, we said in Britain: Lets make hay while the

sun shines. We taxed the companies and

promptly spent the proceeds. The future could

look after itself.

40. You said a rainy day will come so lets get

ready for it. You set up the oil fund, so that you

could invest the proceeds from your windfall to

build a future beyond the time when oil and gas

could pay your bills.

41. Soon the oil fund will be worth $1 trillion, and

many of us in Britain are wondering why we did

not have your foresight.

42. But even if you have a clear vision and the will

to pursue it, you also need the capacity to act

together to make it real. And for that you need a

public realm in which everybody feels at home. A

national hearth around which a family

conversation constantly hammers out a shared

appreciation of the public interest so that publicly

mandated agencies can act with trust and

legitimacy to secure it.

43. People need to feel, in other words, that politics

is something they are part of, not something that

happens far away from their communities and

their lives, that their voice will be heard not

ignored, that whatever is done is done with them

not to them.

44. People need to trust government and public

institutions, to see them as enablers of a better

future, not enemies of enterprise and freedom.

45. And people need to understand that the market

is and must always remain our servant not our

master, that of course we should harness it when

it can help secure the public interest but we

should never surrender to it our right and

responsibility to determine the public interest

ourselves.

46. It is because we had lost confidence in our

public realm and surrendered it to the caprices of

private capital that the crash of 2008 did so much

damage in Britain. We failed to ask what kind of

economy we needed to bind us together and

make us stronger. We let go of the tiller and

allowed the animal spirits we had unleashed to

drag us into overdependence on underregulated

financial industries. And we are still paying the

price.

47. Values; vision and the will to pursue it; and a

trusted public realm animated by politics that

gives everyone a voice. We must all cherish

those virtues because we need them now more

than we ever have before.

[PAUSE]

48. Among the first Europeans to enjoy the

benefits of electric street lighting were the citizens

of Hammerfest, high in the Norwegian Arctic. Not

many people know that! The inauguration of the

Hammerfest lights in 1891 was a landmark in the

first golden age of electricity and it made Norway

a pioneer.

49. Humming wires soon girdled the world and

nothing was ever the same again.

50. Today we stand on the threshold of a second

golden age of electricity. But facing us this time

are two paths, heading in different directions.

51. If we follow the first path, we will electrify

transport by road and rail, as well as heating. We

will achieve a step change in the efficient use of

electricity, and of energy in all its forms. We will

take carbon emissions completely out of

electricity, largely through the use of renewables.

Access to affordable clean electricity will lift

billions of people out of poverty.

52. And all this, on the first path, will be

accomplished everywhere within a single

investment cycle, that is, pretty much by the time

the children of my generation reach our age. It is

they after all who will have to reap the harvest we

sow with our choices today.

53. There are no insurmountable obstacles on this

path, unless they lie in our own nature. We have

the knowledge, the technology, and the wealth to

follow it all the way to its destination.

54. The company you are building here at Statkraft

faces along the first path. Christian nailed your

colours to the mast when he promised that all

your new investment from now on would be in

renewables.

55. You are broadening your offer beyond your

core hydropower business, especially to onshore

and offshore wind, including in Britain. You are

speeding the expansion of community-based

renewables that is turning European electricity

markets upside down and threatening to do the

same in the US.

56. And you are building footholds in what will be

an equally dramatic expansion in renewables in

South America and South Asia.

57. At first sight, the second path bears some

resemblance to the first, at least in its early

stages. The rise of renewable energy continues.

We redouble our efforts to waste less energy.

Each generation of electric cars turns ever more

heads.

58. But in reality the two paths could not be more

divergent.

59. Recently two of the words biggest oil and gas

companies have tried to reassure investors about

the so-called carbon bubble.

60. Might todays high carbon assets end up

stranded by the combination of action by

governments on climate change and the

plummeting cost of renewables? And if so how

should this risk be priced into the value of carbon-

exposed portfolios?

61. The two companies solemnly declared that

there is no bubble and that the business as usual

risk to shareholder value is insignificant.

62. They did acknowledge that governments have

committed themselves to keeping climate change

within 2C. And they seem implicitly to accept

that if governments were to force a shift away

from fossil energy fast enough to stay below that

threshold, some of their assets would indeed be

stranded.

63. But, the companies argue, there is no prospect

of governments keeping this promise. They do

not have the will. Electricity wont displace oil and

gas any time soon.

64. Nor will the disruptive advance of renewables

continue. Thats a - what shall we call it? a

courageous judgement in the light of growing

expectations to the contrary in the City of London

and Wall Street, and the wave of self-criticism by

those utilities who so misread energy politics in

Germany. Even Statkraft burned its fingers there

on gas.

65. But anyway by taking this position these two

companies have also nailed their colours to the

mast. They profess concern about climate

change but want us to lower our ambition, to slow

down the push to displace oil and gas. Change in

the energy system, they are saying, has its own

rhythms and cannot be rushed by the choices

people make through politics about what

outcomes are merely in the public interest.

66. They have chosen the second path, and are

betting the shirts on their own and their

shareholders backs that we will all accept their

invitation to travel along it with them.

67. This is an offer we must refuse.

68. President Obamas science adviser, John

Holdren, says that when it comes to climate

change we need to manage the unavoidable and

avoid the unmanageable. Governments promised

to keep climate change within 2C because in

their judgement thats where the unmanageable

begins. Nothing we have learned since then has

made this look too cautious.

69. The worlds systems of food, water and energy

are tightly linked. They are already under stress,

squeezed between rising middle class demand

from China and other rapidly growing economies

and extremes of temperature and rainfall that

look like the early consequences of climate

change.

70. There can be no food, water, and energy

security without climate security. And a world

without food, water and energy security is an

unmanageable world. Its a world without the trust

and confidence on which cooperation depends;

where the willingness to align around agreed

rules, so crucial for the open global economy,

drains away; where political risk and instability

stifle investment. A world on a slippery slope to

fragmentation and conflict.

71. Moreover, our dependence on fossil energy is

at the heart of a growth model that is corroding

the ecological fabric on whose integrity the entire

economy depends. It consumes resources that

cannot be replenished or substituted; and it fouls

land, air and ocean with its waste. A growth

model that destroys the ecological foundation

destroys itself.

72. This is a greater and more immediate threat

than is widely realized. Here in Norway, looking

towards the ocean and into the Arctic, you grasp

this better than most, and have tried harder than

most to tread lightly. But there will be no

prosperity or security anywhere if we cannot

quickly stabilize the ecological foundation of the

global economy. That will require a new growth

model, liberated from the intellectually and

politically bankrupt neoclassical dogma that

defines the current one.

73. Todays borders in Europe and the Middle East

are largely the product of the First and Second

World Wars.

74. Revanchist forces in Russia are now picking

holes in Europes fontier to the East. Our

dependence on Russias gas weakens our hand

in pressing it to respect its neighbours borders.

75. The way to reduce dependence on Russian

gas is to reduce dependence on gas. It is not, as

some would have us do, to lock ourselves further

into gas-based energy by developing costly

alternative sources including shale gas.

76. The Middle East, from Libya to Iraq, is in

flames and the danger of a greater conflagration

is plain. This poses new risks to security in

Europe. Our dependence on oil and gas from the

Middle East limits our leverage with those from

whom we buy it. The only way to free our hands

is to reduce our dependence not just on Middle

Eastern oil and gas but on oil and gas full stop.

77. So yes, the first path requires a clear choice. It

invites us to draw on our values, mobilize all the

forces at our disposal around a new vision for

energy, summon the will to pursue that vision,

and act to make it reality. It requires us to make

politics work to transform our societies in the

public interest. It will demand struggle and

sacrifice, because the forces of incumbency are

strong and will stop at nothing to resist

transformation.

78. But the first path takes us away from existential

danger. And though the mounting geopolitical

risks will not go away its the only path that will

put us in a better position to manage them.

79. The trouble is, we are not on the first path; not

yet. We are still on the second path. We are

choosing only not to make a choice, acting only

to avoid taking action. The two companies have

noticed that and that is why they think we have

no will.

80. In Britain, yes, we have legally binding carbon

budgets out to 2050. But we are not offering

investors and households the certainty of

outcomes and returns necessary to reach them.

And we have aroused unmeetable expectations

about shale gas, the pursuit of which, far from

uniting the country around a single vision, is

opening up new divisions.

81. Yes, we have a truly pioneering Green

Investment Bank, the worlds first publicly-backed

financial institution designed to draw private

capital on a transformational scale into low

carbon infrastructure. Its great that its

representatives have been in meetings with

Statkraft today. But we withhold from it the

borrowing powers that would really give it

leverage.

82. In Norway you already have carbon neutral

electricity. Norwegians like electric cars. You

have in the past been a champion of carbon

capture and storage, another key piece of this

jigsaw. The oil fund may soon decide to dump its

carbon assets. Your climate diplomacy has set a

global example (and I am delighted that Minister

Brende remains as committed to it as he was

when I first met him as Norways Environment

Minister).

83. But you are still, as a producer like Britain,

deeply locked in to the oil and gas economy.

Norwegian companies want to go on a frontier

binge in the Arctic: it is madness to be developing

new projects there that will only turn a profit

above $100 a barrel. On CCS you pulled the plug

on Mongstad and seem to have run out of steam.

There is no sign of a national vision for energy.

84. We may, each of us, be pointing hopefully

towards the first path. But our feet are still firmly

planted on the second. None of our mainstream

political parties, yours or ours, is offering voters

the choice of the first path or has even articulated

that choice in meaningful political terms.

85. Those who want us to come to an

accommodation with an unwelcome reality rather

than changing it are still winning.

86. But that is not the Norwegian way, nor the

British one.

[PAUSE]

87. A journey along the first path will have many

features. But one stands out. This is something

we can only do if we do it together. This is about

reaching outwards. It is about Big Norway, not

Little Norway.

88. Ibsen, in Peer Gynt, puts into the mouth of the

Mountain King the words vaer deg selv nok.

Hes describing the attitude that makes trolls

different from humans. I suppose you could

translate this loosely as why worry about others

if you are OK?

89. In truth the approach of European nations to

energy has always displayed this kind of

insularity.

90. We cannot do what I have been talking about

unless we do it together as Europeans. It wont

work if we approach it in the spirit of vaer deg

selv nok..

91. There is a particular complementarity in energy

and electricity around the northern seas of

Europe. And Britain and Norway each have

starring roles to play in exploiting this.

92. We must now build a proper integrated grid,

fully connected across borders. We must use that

grid to smooth out peaks and troughs by trading

electricity freely in real time, and by actively

managing demand, across our continent. We will

incidentally get maximum value for cables

between the UK and Norway if we route them

past big wind sources in the North Sea, like

Dogger Bank where Statkraft has a stake.

93. Your capacity to store surplus electricity

generated elsewhere and sell it back into the grid

when needed is a huge asset for Norway and for

all of us. And when we really get moving on CCS

we will wake up to the value of the storage

capacity under the North Sea. Statoil has shown

the way at Sleipner.

94. A project like this would require serious

investment - perhaps some 100 billion over the

next 15-20 years. But the benefits would be

enormous.

95. This would not only usher in a new golden age

of electricity.

96. It would provide the stimulus we need to get

Europe moving again. It would put a new motor at

the heart of a stronger more competitive

economy, better able to withstand global shocks.

It would create high value real economy jobs

spread across all regions, including where jobs

are most needed like the East coast industrial

ports of Britain. It would drive innovation, boost

skills, grow new supply chains and give old ones,

like those in offshore engineering, a new lease of

life.

97. And politically this would offer a new prospect

of progress, hope and common purpose across

our continent, especially for young people. As we

did after the War, we would be taking

responsibility once again for our future.

98. It is for the Norwegian people to decide

Norways national interest. But if I could be your

Prime Minister for a day, I would deploy the oil

fund actively and urgently to jump onto the first

path. Im sure that should include an injection of

capital for Statkraft. Christian, just say the word, I

have the chequebook here.

99. And I would get on the phone to my Nordic

neighbours, to Prime Minister Cameron,

Chancellor Merkel, President Hollande, and to all

their counterparts. I would urge them to join me in

building the shared political vision and mobilizing

the unstoppable coalition that will persuade

investors that the long-discussed plan to build an

integrated European power grid is now a

bankable opportunity.

[PAUSE]

100. Reading the old Norse myths, there is a terrible

inevitability about the chain of events that leads

to the fall of Asgard.

101. As soon as you are told that Odins beautiful

son Baldur has been made impervious to all

anticipated threats, you know he will fall victim to

one that has not been anticipated. As soon as

you learn of the heart-rending effort by Baldurs

grieving mother Frigg to persuade all of Nature to

weep him back into the land of the living, you

know that tears will flow in rivers everywhere

except from the eyes of one mysterious creature

who insists on weeping with dry eyes.

102. And there is something about the onset of the

winter that follows that heralds the final fatal

reckoning between the Gods and their old

enemies the Giants. The end of the world as it

had been foretold. Ragnark

103. The pivotal figure in these myths is Loki, the

shape shifter, with one foot among the Gods and

the other among the Giants. Loki who stands for

fire and light. Loki who more than any figure in

any mythology embodies our own ingenuity in

harnessing fire and light for better or worse.

104. Loki who cannot resist pointing out the hidden

chink in Baldurs armour. Loki who all of a sudden

can only weep only with dry eyes. Loki who

comes with his terrible offspring the wolf and the

serpent to assist in the destruction of the order he

is at once part of and detests; and in his own

destruction.

105. Loki does what he does not because he

chooses to destroy but because destruction is in

his nature. He is clever; he is proud; he has

unquenchable desires. In indulging his desires

and his pride he cannot resist doing what his

cleverness enables him to do.

106. Loki is in all of us. It was Loki who lit up

Hammerfest. It was Loki who lit up Hiroshima and

Nagasaki. He is never still, and for better or for

worse we can see his fleeting footprints

everywhere today.

107. But though we too are clever, and proud, and

driven by unquenchable desires, we also have

values, we have our own will, we can choose

between different paths.

108. In the great Norse poem of creation the

Vluspa there is a haunting account of what

comes to pass after Ragnark. Some say it was

smuggled into an earlier text to bring a pagan

myth into line with Christian resurrection. They

argue that there was no new beginning.

109. But the idea of death followed by regeneration

is as old as we are, and the voice that utters

these evocative lines is surely an ancestral voice.

110. The question for us is not will the old order

give way to something different? Of course it will.

It is happening already.

111. The question is: will the transition to what

comes next be accomplished in an orderly way

by our own will. Or will it accomplish itself in

disorder because for too long our choice was only

not to choose? And in that event, by the time it is

over, will we be in any condition to appreciate

what comes next?

112. Its up to us. If we make the other choice, we

may even see.

.come up

a second time

earth out of ocean

once again green.

The waterfalls flow

an eagle flies over

in the hills

hunting fish.

Without sowing

cornfields will grow -

all harm will be healed,

Baldur will come.

You might also like

- Ireland, Land of The PharaohsDocument332 pagesIreland, Land of The PharaohsIM NotSirius100% (11)

- Accounting Entries in ModulesDocument88 pagesAccounting Entries in ModulesSuresh Joshi100% (2)

- MATM Test Plan DevDocument241 pagesMATM Test Plan DevKrishna TelgaveNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Loss and Damage ProposalDocument68 pagesBangladesh Loss and Damage Proposalclimatehomescribd100% (2)

- Ban Ki Moon LetterDocument6 pagesBan Ki Moon LetterclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Reign of Terror: The Budapest Memoirs of Valdemar Langlet 1944-?1945From EverandReign of Terror: The Budapest Memoirs of Valdemar Langlet 1944-?1945No ratings yet

- AFFIRMATIONS IN ACTION: A Collection of Essays and Selected PoemsFrom EverandAFFIRMATIONS IN ACTION: A Collection of Essays and Selected PoemsNo ratings yet

- 'Boy' by Roald Dahl VocabularyDocument27 pages'Boy' by Roald Dahl VocabularyNadica1954100% (1)

- Annie Besant - An AutobiographyDocument205 pagesAnnie Besant - An AutobiographyGhulam Mustafa100% (1)

- Serbia in Light and Darkness: With Preface by the Archbishop of Canterbury, (1916)From EverandSerbia in Light and Darkness: With Preface by the Archbishop of Canterbury, (1916)No ratings yet

- Fishermen, Knud Dyby and The Danish Resistance - and The Scarlet Pimpernel..Document5 pagesFishermen, Knud Dyby and The Danish Resistance - and The Scarlet Pimpernel..SusdyringNo ratings yet

- The Swiss Family Robinson (Zongo Classics)From EverandThe Swiss Family Robinson (Zongo Classics)Rating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (20)

- The Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian Encounters in New NetherlandFrom EverandThe Shame and the Sorrow: Dutch-Amerindian Encounters in New NetherlandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Spanish BrothersDocument284 pagesSpanish BrothersPaul SimonNo ratings yet

- Derbyherberteafu 00 FursuoftDocument102 pagesDerbyherberteafu 00 Fursuoftceres5No ratings yet

- 50 World’s Greatest Essays: Collectable EditionFrom Everand50 World’s Greatest Essays: Collectable EditionNo ratings yet

- The King in YellowFrom EverandThe King in YellowRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (319)

- Sailing by Starlight: In Search of Treasure IslandFrom EverandSailing by Starlight: In Search of Treasure IslandRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Marie GourdonA Romance of The Lower St. Lawrence by Ogilvy, MaudDocument54 pagesMarie GourdonA Romance of The Lower St. Lawrence by Ogilvy, MaudGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- The Burgomaster's Wife: Tale of the Siege of Leyden (Historical Novel)From EverandThe Burgomaster's Wife: Tale of the Siege of Leyden (Historical Novel)No ratings yet

- Yitzhak Katnelson - Song of The Murdered Jewish PeopleDocument3 pagesYitzhak Katnelson - Song of The Murdered Jewish PeopleGeorge StevensNo ratings yet

- The Boy Who Lost His Birthday: A Memoir of Loss, Survival, and TriumphFrom EverandThe Boy Who Lost His Birthday: A Memoir of Loss, Survival, and TriumphNo ratings yet

- The Autobiography of Goethe: Truth and Poetry: From My Own LifeFrom EverandThe Autobiography of Goethe: Truth and Poetry: From My Own LifeNo ratings yet

- The Camp of the Dog (Cryptofiction Classics - Weird Tales of Strange Creatures)From EverandThe Camp of the Dog (Cryptofiction Classics - Weird Tales of Strange Creatures)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Social Problems A Down To Earth Approach 12Th Edition Henslin Test Bank Full Chapter PDFDocument22 pagesSocial Problems A Down To Earth Approach 12Th Edition Henslin Test Bank Full Chapter PDFprodigalhalfervo2b100% (8)

- The Indian Chief: The Story of A Revolution by Gustave AimardDocument180 pagesThe Indian Chief: The Story of A Revolution by Gustave AimardrenecejarNo ratings yet

- Life Lines Issue 44Document18 pagesLife Lines Issue 44Gerry ParkinsonNo ratings yet

- الغريب الغامض وقصص أخرى 2Document141 pagesالغريب الغامض وقصص أخرى 2mehdimaftouh0No ratings yet

- The Mysterious StrangerDocument74 pagesThe Mysterious Strangertendoesch1994No ratings yet

- The Long NightDocument340 pagesThe Long NightAlexandra PopoviciNo ratings yet

- 0321714113.pdfC++ BESTDocument86 pages0321714113.pdfC++ BESTMilNo ratings yet

- Upload 1Document1 pageUpload 1Patrick D. BowenNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From 911Document6 pagesExcerpt From 911api-232075351No ratings yet

- The Norsemen in The West by Ballantyne, R. M. (Robert Michael), 1825-1894Document164 pagesThe Norsemen in The West by Ballantyne, R. M. (Robert Michael), 1825-1894Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Goldstein V Climate Action Network Et AlDocument74 pagesGoldstein V Climate Action Network Et Alclimatehomescribd100% (1)

- Nordhaus Dec 2016 PaperDocument44 pagesNordhaus Dec 2016 PaperclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Nordhaus Dec 2016 PaperDocument44 pagesNordhaus Dec 2016 PaperclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Air Traffic ControlsDocument28 pagesAir Traffic ControlsclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Petition: Magbilang, o Mapabilang, Sa Mga Biktima NG Climate Change?"Document65 pagesPetition: Magbilang, o Mapabilang, Sa Mga Biktima NG Climate Change?"climatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- The Signing Ceremony of The Paris Agreement in New York On 22 AprilDocument7 pagesThe Signing Ceremony of The Paris Agreement in New York On 22 AprilMatt MaceNo ratings yet

- NGO Letter To Green Bond PrinciplesDocument4 pagesNGO Letter To Green Bond PrinciplesclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Climate Change-Related Legal and Regulatory Threats Should Spur Financial Service Providers To Action 04.05.2016Document12 pagesClimate Change-Related Legal and Regulatory Threats Should Spur Financial Service Providers To Action 04.05.2016climatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Open Letter Backing Coal Mine MoratoriumDocument1 pageOpen Letter Backing Coal Mine MoratoriumclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- GCF: 2015 Strategy SuggestionsDocument90 pagesGCF: 2015 Strategy SuggestionsclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- US China Climate Fact SheetDocument7 pagesUS China Climate Fact SheetclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Paris Agreement and Fifth Carbon Budget CCC Letter To RT Hon Amber RuddDocument8 pagesParis Agreement and Fifth Carbon Budget CCC Letter To RT Hon Amber RuddclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- In Support of A Paris Climate AgreementDocument1 pageIn Support of A Paris Climate AgreementclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- EU COP21 ConclusionsDocument12 pagesEU COP21 ConclusionsclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Marshall Islands Letter To International Maritime OrganizationDocument3 pagesMarshall Islands Letter To International Maritime OrganizationclimatehomescribdNo ratings yet

- Controlling Money Laundering in India - Problems and PerspectivesDocument50 pagesControlling Money Laundering in India - Problems and PerspectivesMadhuritaNo ratings yet

- GCG in EnglishDocument16 pagesGCG in EnglishSara NuranggrainiNo ratings yet

- PNB V. Ca & PadillaDocument1 pagePNB V. Ca & PadillaMlaNo ratings yet

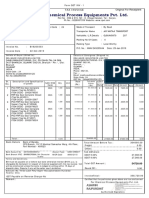

- Manisha Raval: Date VCH Type VCH No. 12-04-2017 3Document8 pagesManisha Raval: Date VCH Type VCH No. 12-04-2017 3Praveen RawalNo ratings yet

- Timesheet Meares Area Minahasa March 2021Document9 pagesTimesheet Meares Area Minahasa March 2021Angela LoleslolesNo ratings yet

- Gitam Student Profiles PDFDocument28 pagesGitam Student Profiles PDFCharan RajNo ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument20 pagesSynopsisMohd ShahidNo ratings yet

- APPLICATION FORM For Delivery Channel Services: Date of Birth: (DD-MM-YY)Document2 pagesAPPLICATION FORM For Delivery Channel Services: Date of Birth: (DD-MM-YY)jay shahNo ratings yet

- Corporate Governance and Climate ChangeDocument64 pagesCorporate Governance and Climate ChangenavneetproNo ratings yet

- Foriegn Exchange Manual 2002Document82 pagesForiegn Exchange Manual 2002Mirza AnishNo ratings yet

- Developing Singapore's Corporate Bond Market: Building A Liquid Government Benchmark Yield CurveDocument6 pagesDeveloping Singapore's Corporate Bond Market: Building A Liquid Government Benchmark Yield CurveMOHAMED RIZWANNo ratings yet

- Habitech PanchtatvaDocument6 pagesHabitech Panchtatvamadhukar sahayNo ratings yet

- Statement of Undisputed Material Facts Operation Choke PointDocument48 pagesStatement of Undisputed Material Facts Operation Choke PointThePoliticalHatNo ratings yet

- Isf WSC Handball 2018 - Bulletin 2 0Document8 pagesIsf WSC Handball 2018 - Bulletin 2 0olazagutiaNo ratings yet

- Sample Resume For Bank Teller With No ExperienceDocument7 pagesSample Resume For Bank Teller With No Experienceafiwfnofb100% (1)

- Issue Date Issue Type Issuer Industry: US$ Bond Issues From High Grade Companies in US (Mar-09) - (Hypothetical Data)Document10 pagesIssue Date Issue Type Issuer Industry: US$ Bond Issues From High Grade Companies in US (Mar-09) - (Hypothetical Data)ayush jainNo ratings yet

- Peer-to-Peer Lending in India: An Industry Analysis: August 2020Document13 pagesPeer-to-Peer Lending in India: An Industry Analysis: August 2020AshNo ratings yet

- Oracle R12 Setup ChecklistDocument30 pagesOracle R12 Setup ChecklistAsif SayyedNo ratings yet

- EChallan ManualDocument4 pagesEChallan ManualUtkarsh GuptaNo ratings yet

- J&K BankDocument7 pagesJ&K BankAzhar Shokin100% (1)

- Food Allowance May MonthDocument3 pagesFood Allowance May MonthKalyanaraman RamakrishnanNo ratings yet

- International Banking & FinanceDocument10 pagesInternational Banking & FinanceVenkateshNo ratings yet

- Invoice1 PDFDocument4 pagesInvoice1 PDFcpe plNo ratings yet

- TheWallStreetJournal-22 April 2019 PDFDocument40 pagesTheWallStreetJournal-22 April 2019 PDFMauroNo ratings yet

- Colt 1st Year (1964) Ar-15 Sp1... 3-Digit Sn#..Document56 pagesColt 1st Year (1964) Ar-15 Sp1... 3-Digit Sn#..anon_835518017No ratings yet

- CH 08 Clearing House SystemDocument13 pagesCH 08 Clearing House SystemMoshhiur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Roman V ABC Digest - Warehouse ReceiptsDocument1 pageRoman V ABC Digest - Warehouse ReceiptsLook ArtNo ratings yet

- 1.permanent Account Number (Pan)Document10 pages1.permanent Account Number (Pan)akashNo ratings yet