Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Colonic Polyps

Colonic Polyps

Uploaded by

Indra AjaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Colonic Polyps

Colonic Polyps

Uploaded by

Indra AjaCopyright:

Available Formats

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF GASTROENTEROLOGY

Copyright 1998 by Am. Coll. of Gastroenterology

Published by Elsevier Science Inc.

Vol. 93, No. 4, 1998

ISSN 0002-9270/98/$19.00

PII S0002-9270(98)00053-7

Colonic Polyps: Experience of 236 Indian Children

Ujjal Poddar, M.D., D.M., B. R. Thapa, M.D., Kim Vaiphei, M.D., and Kartar Singh, M.D., D.M.

Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Department of Gastroenterology and Pathology, Postgraduate Institute of

Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

Objectives: We studied the clinical spectrum, histology, and malignant potential of colonic polyps in Indian

children (<12 yr). Methods: Two hundred thirty-six children with colonic polyps were studied from January

1991 to October 1996. They were evaluated clinically

and colonoscopic polypectomy was done. Children with

five or more juvenile polyps were labeled as having

juvenile polyposis and serial colonoscopic polypectomies

were done every 3 wk. Colectomy was performed when

there were intractable symptoms or clearing of the polyps by colonoscopy was not possible. Histological examination of the polyps was done. Follow-up colonoscopy

was done in children with juvenile polyposis only.

Results: The mean age of these children was 6.12 6 2.7

yr, with a male preponderance (3.5:1). Rectal bleeding of

a mean duration of 14 6 16 months was the presenting

symptom in 98.7%. Solitary polyps were seen in 76%,

multiple polyps in 16.5%, and juvenile polyposis in 7%

(n 5 17) of the children. A majority (93%) of the polyps

were juvenile and 85% were rectosigmoid in location.

Adenomatous changes, seen in 11%, were more common

in juvenile polyposis (59%) than in juvenile polyps (5%).

Among those with juvenile polyposis, colon clearance

was achieved in eight, six required colectomy for intractable symptoms, and three were still on the polypectomy

program. Polyps recurred in 5% of children with juvenile polyps and 37.5% of those with juvenile polyposis.

Conclusions: Juvenile polyps remain the most common

colonic polyps in children. A significant number of cases

of polyps are multiple and proximally located, which

emphasizes the need for total colonoscopy in all. Juvenile

polyps should be removed even if asymptomatic because

of their neoplastic potential. Colonoscopic polypectomy

is effective even in juvenile polyposis. Surveillance

colonoscopy is required in juvenile polyposis only. (Am

J Gastroenterol 1998;93:619 622. 1998 by Am. Coll.

of Gastroenterology)

of rectal bleeding in children (1). Polyps occur in as many

as 1% of children and 90% of these are juvenile polyps (2).

Traditionally, juvenile polyps have been reported to be

solitary and rectosigmoid in location in 80 90% of cases

(35). A recent study, however, done on a small number of

children, has shown that .50% polyps are multiple and

located proximal to the sigmoid colon (6).

Juvenile polyps are generally thought to be hamartomatous lesions with little malignant potential. Some reports,

however, have documented the occurrence of colorectal

adenomas and carcinomas in patients with single juvenile

polyps as well as those with juvenile polyposis (712). Thus

the nature of association between juvenile polyps and colorectal neoplasia is controversial. We present here the clinical

spectrum, histology, and malignant potential of colonic polyps seen on colonoscopy in a large number of Indian children (#12 yr).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Two hundred thirty-six children with colonic polyps were

studied in the Pediatric Gastroenterology center of our institute from January 1991 to October, 1996. After a clinical

evaluation, fiberoptic colonoscopy was done in all the children. In the initial phase of the study, colonoscopic preparation was done with liquid diet and laxative (liquid paraffin) for 2 days and saline enema 1 h before the procedure.

For the last 2 yr, we have started using polyethyleneglycol

(PEG) to prepare the child on the same day of the procedure.

Diazepam (0.5 mg/kg, intravenous [IV]) or ketamine (1

mg/kg, IV) in young children (,5 yr), was used for sedation

as and when required, but general anesthesia was not used

in any patient. Colonoscopy was done with PCF or CFP1OI

(OLYMPUS) scope. Polyps seen on colonoscopy were removed by the snare cautery technique. Children were observed for 6 24 h after polypectomy to detect any complications, such as hemorrhage or perforation.

Children with more than five juvenile polyps were labeled as having juvenile polyposis (12) and their detailed

family history regarding juvenile polyposis and colon carcinoma was recorded. All these children were examined

carefully to detect any associated congenital defects and

esophagogastroduodenoscopy and barium meal followthrough study was done at least once. Serial colonoscopic polypectomies were done in these patients every 3

INTRODUCTION

Rectal bleeding is an alarming event for children as well

as for parents. Polyps are among the most common causes

Received Jan. 3, 1997; accepted Dec. 22, 1997.

619

620

PODDAR et al.

AJG Vol. 93, No. 4, 1998

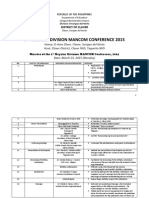

TABLE 1

Distribution of Polyps (Excluding Juvenile Polyposis)

Site

No. of

Polyps

(%)

Rectum

Sigmoid

Descending colon

Transverse colon

Ascending colon/cecum

193 (72.0)

52 (19.5)

10 (3.7)

7 (2.5)

5 (2.0)

wk until colon clearance was achieved. Surgery (total colectomy, mucosal proctectomy, and ileoanal anastomosis)

was performed when there were intractable symptoms despite repeated colonoscopic polypectomies, or clearing of

the polyps by colonoscopy was not possible. After clearance

of the colon, surveillance colonoscopy was done whenever

the child was symptomatic or twice yearly, whichever was

earlier. Polyps were removed by snare polypectomy and

surgical specimens were subjected to histological examination. Associated dysplasia, if present, was graded according

to the WHO grading system (13).

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean 6SD. Differences

between groups were analyzed using x2 and Z-test; p , 0.05

was considered significant.

RESULTS

During the study period, 459 colonoscopies were done in

382 children for various indications and 236 of them

(61.7%) had colonic polyps. The mean age of these latter

children was 6.12 6 2.7 yr (range 212 yr); male:female

ratio was 3.5:1. The mean duration of symptoms was 14 6

16 months (range 2 wk 8 yr). Bleeding per rectum was the

presenting symptom in all except three children, and it was

intermittent, fresh, and usually painless. Prolapse of mass

per rectum was present in 30, pain abdomen in 10, colitislike symptoms in five, and two each had diarrhea and

recurrent intussusception.

A majority of the children (76%) had solitary polyps.

There were both sessile and pedunculated polyps, and size

varied from 530 mm. Juvenile polyposis was diagnosed in

17 (7%) cases; one of them had polyps in the stomach and

terminal ileum also. Thirty-nine (16.5%) children had multiple polyps (two to five in number). Table 1 shows the

distribution of polyps in the colon. Two hundred sixty-seven

polyps were removed from 219 children (excluding 17 children with juvenile polyposis). One hundred fifty-five children had polyps in the rectum, 41 in the sigmoid, seven in

both rectum and sigmoid, and three each had polyps in both

rectum and descending colon and rectum and transverse

colon; seven had polyps in the descending colon and three

had polyps in the transverse colon. Children with juvenile

polyposis had polyps distributed throughout the colon, ex-

cept in two, who had six polyps each in the transverse colon.

Overall, 201 (85%) had polyps in the rectosigmoid area.

One hundred fifty-two children had polyps available for

histological examination, 142 (93%) of which had juvenile

polyps; five each had hyperplastic and inflammatory polyps.

Adenomatous changes (dysplasia) were seen in 17 (11%)

children with juvenile polyps. Significantly, this was more

common in juvenile polyposis (59%) than in juvenile polyps

(5%) (p , 0.001). Of the seven children with adenomatous

changes in juvenile polyps, five had solitary polyps and one

each had two and three polyps, respectively. Associated

dysplasia was focal and low-grade (Fig. 1A, B).

After initial polypectomy, 10 (5%) children with juvenile

polyps had recurrence. Eight of these had synchronous

polyps (within 6 months of initial polypectomy), whereas

two had metachronous (. 6 months after initial polypectomy) polyps and none had adenomatous changes.

Among the children with juvenile polyposis, none had a

family history of the same or any associated congenital

defects. Colon clearance was achieved in eight children after

an average 5.3 polypectomy sessions. On followup (28 6 15

months) three (37.5%) of them had recurrence of polyp

requiring repeat polypectomy, but none had adenoma or

carcinoma. Surgery was needed in six of the children because of intractable symptoms, and three of them were still

on the polypectomy program at the time of reporting. In

comparison to juvenile polyps (Table 2), children with juvenile polyposis were significantly older, had longer duration of symptoms, greater number of polyps, more adenomatous changes in polyps, and required more polypectomy

sessions to clear the colon. However, there was no significant difference in gender ratio and presentation, such as

rectal bleeding. The total number of polypectomy sessions

was 310 and colonic perforation occurred only once, but

none had significant hemorrhage.

DISCUSSION

Juvenile polyps are the most common tumors of the

gastrointestinal tract in children. The reported prevalence of

colonic polyps in children undergoing colonoscopy for various indications is 4 17.5% (14, 15). In the present series it

was 61.7%. This high figure may be due to the fact that the

most common indication for colonoscopy in our center is

painless rectal bleeding and inflammatory bowel disease (a

common indication for colonoscopy in the West) (12) is rare

in children in our country (16). The clinical presentation of

children with polyps in our study was similar to other

reported series (3, 6, 14).

As reported in the literature (6, 14, 17), the most common

type of polyp seen in our study was also juvenile polyp

(93%). Interestingly, however, we did not encounter even a

single case of adenomatous polyp, whereas the reported

incidence is 23% in other series (6, 14, 17). This possibly

may be due to the younger age of our patients and a low

prevalence of adenomatous polyp in our population (18).

AJG April 1998

COLONIC POLYPS IN INDIAN CHILDREN

621

FIG. 1. (A) Low-power photomicrograph showing distended glands with inflammatory cell exudate within the lumen. In addition, there are glands showing

features of dysplasia (arrow) (hematoxylin and eosin, 350). (B) High-power photomicrograph showing one of the glands having dysplastic lining epithelium,

i.e., increase in nucleocytoplasmic ratio, stratification, prominent nucleoli, and relative lack of goblet cells (hematoxylin and eosin, 3550).

TABLE 2

Comparison Between Juvenile Polyps and Juvenile Polyposis

Age (yrs)

Gender (M:F)

Duration of symptoms

(months)

Rectal bleeding

Polyps localized to

rectosigmoid

Adenomatous changes

Polypectomy (session/

child)

Juvenile

Polyps

(n 5 219)

Juvenile

Polyposis

(n 5 17)

p Value

5.97 6 2.62

3.5:1

12.24 6 13.15

7.68 6 2.95

3.2:1

33.0 6 27.0

,0.05

NS

,0.001

99%

90%

5%

1.04 6 0.20

94%

0%

59%

4.76 6 3.72

NS

,0.001

,0.001

,0.001

It generally has been accepted that 90% of juvenile polyps

are solitary and located in the rectum or sigmoid (3, 6, 14,

16, 17, 19). There is some suggestion that with the introduction of fiberoptic colonoscopy this picture has

changed. Two series (6, 15) have recently shown that

5358% of polyps are multiple and 30 60% are proximal

to the sigmoid colon. However, in both these studies the

number of children was small. In our study, 24% of the

children had multiple polyps and 15% had polyps proximal to the sigmoid colon. Our results are similar to those

of a recently published series (14) where the authors

found polyps in the rectosigmoid area in two-thirds of

cases and 96% had solitary polyps. This shows that,

although a majority of children had solitary polyps in the

rectosigmoid area, a significant number had multiple and

proximally located polyps, which reemphasizes the need

for doing total colonoscopy in all children with unexplained rectal bleeding.

Juvenile polyps are generally considered benign hamartomas. So far only five cases of adenomatous changes in

solitary juvenile polyps (9, 15) and two cases of colorectal

malignancy in juvenile polyps have been documented in the

pediatric age group (10, 11). We have seen adenomatous

changes in seven (5.6%) children with juvenile polyps. In all

these cases this was focal and low-grade dysplasia. Therefore, juvenile polyps carry a small but definite neoplastic

potential and require polypectomy in all cases even if

asymptomatic.

There is no doubt that juvenile polyposis is a premalignant condition (9, 12). The reported incidence of adenomatous changes in this condition is as high as 47% (12). We

have also seen adenomatous changes in 58.8% of cases and

in all of them it was focal and low-grade dysplasia. None of

them had associated adenoma or carcinoma, perhaps due

to the younger age of patients in our series in comparison

to others (9, 12). In view of the risk of malignancy, this

group of children requires surveillance colonoscopy 23

times/yr, after their colons are cleared of polyps. In our

study, three of eight children had recurrence of polyps on

surveillance colonoscopy. On the other hand, surveillance

and follow-up has not been recommended in juvenile

polyps (20).

The recurrence of juvenile polyps after polypectomy is

rare (1.7%) (3). In our series polyps recurred in 4.5% cases.

It is possible that we might have missed some of the polyps,

thus accounting for predominantly synchronous polyps.

In conclusion, juvenile polyps remain the most common

colonic polyps in children. Though a majority of these are

solitary and rectosigmoid in location, in a significant number of cases polyps are multiple and proximally located,

which emphasizes the need for total colonoscopy in all.

Juvenile polyps should be removed in all cases not only

because of bleeding but also for their neoplastic potential.

Colonoscopic polypectomy is effective and safe in children

even with juvenile polyposis. Surveillance colonoscopy is

required in juvenile polyposis.

Reprint requests and correspondence: Dr. B. R. Thapa, Additional

Professor, Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Postgraduate Institute of

Medical, Education and Research, Chandigarh-160012, India.

622

PODDAR et al.

REFERENCES

1. Holgersen LO, Mossberg SM, Miller RE. Colonoscopy for rectal

bleeding in children. J Pediatr Surg 1978;13:835.

2. Gelb A, Minkowitz S, Tresser M. Rectal and colonic polyps occurring

in young people. NYS J Med 1962;62:513 8.

3. Roth SI, Helwig EB. Juvenile polyps of the colon and rectum. Cancer

1963;16:468 79.

4. Toccalino H, Guastavino E, De Pinni F, et al. Juvenile polyps of the

rectum and colon. Acta Paediatr Scand 1973;62:337 40.

5. Shermeta DW, Morgan WW, Eggleston J, et al. Juvenile retention

polyps. J Pediatr Surg 1969;4:2115.

6. Mestre JR. The changing pattern of juvenile polyps. Am J Gastroenterol 1986;81:312 4.

7. Friedman CJ, Fechner RE. A solitary juvenile polyp with hyperplastic

and adenomatous glands. Dig Dis Sci 1982;27:946 8.

8. Berg HK, Herrera L, Petrelli N, et al. Mixed juvenile adenomatous

polyp of the rectum in an elderly patient. J Surg Oncol 1985;29:40 2.

9. Giardiello FM, Hamilton SR, Kern SE, et al. Colorectal neoplasia in

juvenile polyposis or juvenile polyps. Arch Dis Child 1991;66:9715.

10. Liu-TH, Chen MC, Tseng HC. Malignant change of a juvenile polyp

of colon: A case report. Chin Med J 1978;4:434 9.

AJG Vol. 93, No. 4, 1998

11. Schilla FW. Carcinoma in a rectal polyp. Am J Surg 1954;4:434 9.

12. Jass JR, Williams CB, Bussey HJR, et al. Juvenile polyposisa

precancerous condition. Histopathology 1988;13:619 30.

13. Jass JR, Sobin LH. World Health Organization: Histological typing of

intestinal tumors, 2nd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1989.

14. Latt TT, Nicholl R, Domizio P, et al. Rectal bleeding and polyps. Arch

Dis Child 1993;69:144 7.

15. Cynamon HA, Milov DE, Andres JM. Diagnosis and management of

colonic polyps in children. J Pediatr 1989;114:593 6.

16. Thapa BR, Mehta S. Diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy in children: Experience from a pediatric gastroenterology centre in India.

Indian Pediatr 1991;28:3839.

17. Kumar N, Anand BS, Malhotra V, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy

North Indian experience. J Assoc Physicians India 1990;38:272 4.

18. Bhargava DK, Chopra P. Colorectal adenomas in a tropical country.

Dis Colon Rectum 1988;31:6923.

19. Jalihal A, Misra SP, Arvind AS, et al. Colonoscopic polypectomy in

children. J Pediatr Surg 1992;27:1220 2.

20. Nugent KP, Talbot IC, Hodgson SV, et al. Solitary juvenile polyps:

Not a marker for subsequent malignancy. Gastroenterology 1993;105:

698 700.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Virgil Donati InterviewDocument3 pagesVirgil Donati InterviewPedro MirandaNo ratings yet

- McGraw Hill Personal Finance Chapter 9Document2 pagesMcGraw Hill Personal Finance Chapter 9Kathleen0% (1)

- Clinica Chimica Acta: SciencedirectDocument6 pagesClinica Chimica Acta: SciencedirectIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research NoteDocument7 pagesThe Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A Research NoteIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: U.S. Normative Data and Psychometric PropertiesDocument8 pagesThe Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: U.S. Normative Data and Psychometric PropertiesIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- Valganciclovir Dosing According To Body Surface Area and Renal Function in Pediatric Solid Organ Transplant RecipientsDocument8 pagesValganciclovir Dosing According To Body Surface Area and Renal Function in Pediatric Solid Organ Transplant RecipientsIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- 1Document8 pages1Indra AjaNo ratings yet

- Mediastinal Masses in ChildrenDocument20 pagesMediastinal Masses in ChildrenIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Buspirone, A Fundus-Relaxing Drug, in Patients With Functional DyspepsiaDocument7 pagesEfficacy of Buspirone, A Fundus-Relaxing Drug, in Patients With Functional DyspepsiaIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- Ajg 2010151 ADocument8 pagesAjg 2010151 AIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- Red Blood Cell Transfusion: Decision Making in Pediatric Intensive Care UnitsDocument7 pagesRed Blood Cell Transfusion: Decision Making in Pediatric Intensive Care UnitsIndra AjaNo ratings yet

- Breast ImagingDocument14 pagesBreast ImagingMelissa TiofanNo ratings yet

- Carpentry NC II - COCsDocument6 pagesCarpentry NC II - COCsNestor LacsonNo ratings yet

- CCI Risk Assessment Blank FormDocument5 pagesCCI Risk Assessment Blank FormdphotoportsmouthNo ratings yet

- Secretary State's Standards Modern Zoo PracticeDocument4 pagesSecretary State's Standards Modern Zoo PracticePrunar FlorinNo ratings yet

- Work Environment Survey - Wiki PDFDocument10 pagesWork Environment Survey - Wiki PDFCyril AngkiNo ratings yet

- Olympus TJF-Q180V - Reprocessing ManualDocument118 pagesOlympus TJF-Q180V - Reprocessing ManualMarckus BrodyNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Disability and Psychotic Disorders of Adult EpilepsyDocument0 pagesIntellectual Disability and Psychotic Disorders of Adult EpilepsyRevathi SelvapandianNo ratings yet

- Govt SchemesDocument144 pagesGovt SchemesGorakhnath MethreNo ratings yet

- Tiffin Bark Park Registration Form 2016Document2 pagesTiffin Bark Park Registration Form 2016Keith HodkinsonNo ratings yet

- ApamargaDocument18 pagesApamargaShantu ShirurmathNo ratings yet

- Minimally Invasive Lumbar Spine SurgeryDocument29 pagesMinimally Invasive Lumbar Spine SurgerySourabh AlawaNo ratings yet

- The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) For Assessing The Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-AnalysisDocument21 pagesThe Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) For Assessing The Quality of Nonrandomized Studies in Meta-Analysiscygnus112No ratings yet

- S. Woolley - Children of Jehovah's Witnesses and Adolescent Jehovah's Witnesses - What Are Their RightsDocument5 pagesS. Woolley - Children of Jehovah's Witnesses and Adolescent Jehovah's Witnesses - What Are Their RightsMarco Aurélio Vogel Gomes de MelloNo ratings yet

- Mancom MinutesDocument10 pagesMancom MinutesTetzie SumayloNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Roflumilast Foam, 0.3%, in Patients With Seborrheic Dermatitis - PMCDocument19 pagesEfficacy of Roflumilast Foam, 0.3%, in Patients With Seborrheic Dermatitis - PMCPedro Mercado PuelloNo ratings yet

- BS 7562 5 IrrigationDocument32 pagesBS 7562 5 IrrigationSana UllahNo ratings yet

- Project Design On Disaster Preparedness Seminar Auto Saved)Document4 pagesProject Design On Disaster Preparedness Seminar Auto Saved)Paolo AlconeraNo ratings yet

- Factsheet - Imported Food Control Act 1992Document1 pageFactsheet - Imported Food Control Act 1992Fitria MaurinaNo ratings yet

- Socio-Cultural Representations of The VaginaDocument17 pagesSocio-Cultural Representations of The VaginaKatzenn MinzeNo ratings yet

- UNIT 2 - Bi TPDocument6 pagesUNIT 2 - Bi TPPablo TrungNo ratings yet

- HSE-SAFETY-Plant Inspection ChecklistDocument3 pagesHSE-SAFETY-Plant Inspection ChecklistsantoshNo ratings yet

- DR Vernon Coleman How Many People Are The Vaccines KillingDocument5 pagesDR Vernon Coleman How Many People Are The Vaccines KillingGeorge KourisNo ratings yet

- Touchstone 2 (2nd) WBwerwerwerDocument105 pagesTouchstone 2 (2nd) WBwerwerwerIgnacio CastellanosNo ratings yet

- Inserting An Indwelling CatheterDocument4 pagesInserting An Indwelling CatheterMarcia AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Bell V Tavistock JudgmentDocument38 pagesBell V Tavistock JudgmentAikee MaeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Tissues Glands and MembranesDocument84 pagesChapter 4 Tissues Glands and MembranesSofia MorenoNo ratings yet

- When More Pain Is Preferred To LessDocument6 pagesWhen More Pain Is Preferred To LesstestNo ratings yet

- Complications of Labor & DeliveryDocument7 pagesComplications of Labor & DeliveryPatricia Anne Nicole CuaresmaNo ratings yet