Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Sciencedirect

Uploaded by

dalimahOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Sciencedirect

Uploaded by

dalimahCopyright:

Available Formats

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 8 (2014) 281285

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders

Journal homepage: http://ees.elsevier.com/RASD/default.asp

Evaluation of the concurrent validity of a skills assessment for

autism treatment

Angela Persicke a, Michele R. Bishop a, Christine M. Coffman a,

Adel C. Najdowski a, Jonathan Tarbox a,*, Kellee Chi b, Dennis R. Dixon a,

Doreen Granpeesheh a, Amanda N. Adams b, Jina Jang a, Jennifer Ranick a,

Megan St. Clair a, Amy L. Kenzer a, Sara S. Sharaf a, Amanda Deering a

a

b

Center for Autism and Related Disorders, United States

California State University, Fresno, United States

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 5 December 2013

Accepted 10 December 2013

Accurate assessment is a critical prerequisite to meaningful curriculum programming for

skill acquisition with children with autism spectrum disorder. The purpose of this study

was to determine the validity of an indirect skills assessment. Concurrent validity of the

assessment was evaluated by contrasting parent responses to participants abilities, as

indicated by direct observation of those skills. The degree to which parent report and

direct observation were in agreement was measured by Pearson correlation coefcient for

each curriculum area. Results indicated moderate to very high levels of agreement

between parent report and direct observation of the behaviors. Results are discussed in

terms of implications for efciency of assessment and treatment.

2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Skills assessment

Curriculum

Validity

The use of applied behavior analysis (ABA) for the treatment of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has been welldocumented as effective in the research literature (Matson & Smith, 2008). Several key variables to effective intervention

programs have been identied, one of which includes pairing behavior analytic procedures with an individualized

comprehensive curriculum tailored to the unique needs of each child (American Academy of Child and Adolescent

Psychiatry, 1999; Hancock, Cautilli, Rosenwasser, & Clark, 2000; Lovaas, 2003). In order to develop curriculum programs for

children with ASD that are specic to their individual needs, comprehensive assessment is required, and results of such

assessment must guide curriculum design and selection of treatment targets (Love, Carr, Almason, & Petursdottir, 2009).

Failing to conduct a comprehensive assessment may lead to deleterious effects, as discussed below.

Within the context of ASD treatment, the goal of conducting an assessment is to gain an accurate and thorough

understanding of how a child functions across all relevant domains. This enables the clinician to determine which skills are

decit and address these accordingly. Assessment also helps the clinician to identify a childs strengths, which allows the

clinician to build off of these skills (e.g., if the child is a good reader, textual prompts might be helpful for teaching other

skills) and also avoid wasting valuable time teaching skills in areas where the child has no need for intervention.

When a comprehensive assessment is not conducted, clinicians are more likely to develop treatment programs for

children using a cookbook approach, that is to say, teaching step-by-step from a curriculum, instead of based on

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +1805 379 4000.

E-mail address: j.tarbox@centerforautism.com (J. Tarbox).

1750-9467/$ see front matter 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.12.011

282

A. Persicke et al. / Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 8 (2014) 281285

the childs needs. This can lead to moving too far ahead with a skill by teaching beyond age-appropriateness and/or

teaching skills that are too advanced for the child or even nonfunctional and irrelevant to his/her daily life (Gould,

Dixon, Najdowski, Smith, & Tarbox, 2011). Absence of assessment can also lead to the development of a lopsided or

unbalanced curriculum, wherein programs focus too heavily in one or two areas while ignoring other important areas

(e.g., focusing solely on language and ignoring social, motor, and adaptive skills; Gould et al., 2011). Given the potential

adverse side effects of poor assessment, the importance of proper assessment cannot be ignored. Ultimately, curriculum

programming without guidance leads to wasting valuable teaching time and hindering the childs ability to reach his/

her maximum potential.

Assessment can be performed using various methods including direct observation, indirect assessment (verbal report), or

a combination of the two. From a behavior analytic perspective, direct observation is considered the gold standard (Cooper,

Heron, & Heward, 2007); however, it not only requires trained observers but also must be implemented systematically

across multiple observations for a duration of time that is sufcient to capture a valid sample of behavior (Sigafoos, Schlosser,

Green, OReilly, & Lancioni, 2008). Using solely direct observation to assess all areas of human functioning can be quite timeconsuming and resource-intensive (Gould et al., 2011), especially for older children who require assessment of skills starting

from early childhood to current chronological age. Further, in an effort to obtain reliable information, only a limited number

of behaviors can be observed during any one observation (Matson, 2007). Given these requirements, the use of direct

observation alone may be unrealistic in some cases and indirect assessments such as rating scales, checklists, and

questionnaires may be a more practical option (Sigafoos et al., 2008). Indirect assessment can be combined with direct

observation when the rater is uncertain whether the child is able to exhibit the skill, thereby yielding a reasonable

compromise between the ability to conduct a comprehensive assessment efciently and doing so with the highest degree of

accuracy possible (Gould et al., 2011).

There has been ample psychometric research demonstrating that indirect assessments can be valid methods to measure a

number of domains such as adaptive skills (e.g., Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales-Second Edition [VABS-II]; Sparrow,

Cicchetti, & Balla, 2005) and behavior function (e.g., Questions About Behavioral Function [QABF]; Matson & Vollmer, 1995).

However, there is little to no published research that has evaluated the validity of skills assessments for the treatment of ASD.

Unfortunately, the most commonly used assessments for ABA treatment planning have not undergone even the most basic

psychometric evaluations (Gould et al., 2011).

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the validity of the Skills1 Assessment. The Skills Assessment is part of a

larger web-based system designed for the management of autism treatment, which includes a curriculum, an assessment

linked directly to it, an indirect functional assessment for challenging behavior, a behavior intervention plan builder, as well

as progress tracking capabilities for challenging behavior reduction and skill acquisition (http://www.skillsforautism.com/).

The concurrent validity of the Skills Assessment was evaluated by comparing the results of parent report to data collected

from direct observation of skills.

1. Method

1.1. Participants and setting

Participants were recruited from Southern and Central California and Central Arizona via email and postings in various

social media outlets and community. Participation was limited to individuals with a current DSM-IV diagnosis of autism or a

related developmental disorder. Additionally, participation was limited to individuals between the ages of three and ten

years old at the onset of the study. A total of 42 participants were identied and included in the study. Of the participants

selected, three were not included in nal data analyses. Two of these participants were terminated due to substantial child

noncompliance across three consecutive direct observation sessions; thus collected data were deemed inaccurate. The third

participant withdrew due to scheduling conicts.

For the remaining 39 participants, age in months ranged from 37 to 131 with a mean age of 81.23 months. Thirty-three of

the 39 participants included in the study were male (male to female ratio was 5.5:1). Thirty-three children had a diagnosis of

Autistic Disorder, 2 children were diagnosed with Aspergers Disorder, and 1 child with PDD-NOS according to DSM-IV

diagnostic criteria veried through diagnostic reports by independent licensed professionals for each participant. The 3

remaining children were diagnosed with multiple other developmental disorders including cerebral palsy, developmental

delay, speech/language delay, visual impairment, Developmental Language Disorder, Downs Syndrome, Hypotonia, and

global delays.

Sessions for 27 participants were conducted in the home and sessions for the other 12 participants were conducted at a

center specializing in early intensive behavioral intervention for children with ASD. Home-based sessions were scheduled at

the familys convenience and occurred one to ve times per week with no more than one session per day. Home-based

sessions were between 30 and 60 min in duration. Center-based sessions were scheduled daily for shorter durations (15

45 min). The maximum total duration of direct observation sessions for any individual participant was 30 h and ranged from

6 to 30 h across participants, with a mean of 17.3 h. The study was conducted over a period of 13 months. Participation in the

study ranged from 10 to 233 calendar days (including weekends). The number of days that any participant remained in the

study was dependent on frequency and duration of sessions during each week.

A. Persicke et al. / Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 8 (2014) 281285

283

1.2. Materials

All data were collected by hand using pen and paper and raw data were entered into a spreadsheet by a data entry team.

Materials that were familiar to participants were used for direct observation sessions, whenever such materials were

available. For example, many participants owned items such as books, balls, puzzles or other games, toothbrushes, and

clothing, and these items were used during direct observation sessions. Experimenters brought any additional materials to

the home or center, as needed. If a required item for any given probe was not provided or not readily available in the probe

setting, then the skill was not probed. For example, some items in the Adaptive domain involve the use of a washing machine

which was not available for the participants in the center. Other items in the Motor domain involve climbing stairs or

playground related skills and these materials were not readily available for many participants in the home setting.

1.3. Skills Assessment

The Skills Assessment is a comprehensive assessment that addresses over 3000 skills across every domain of child

development. The domains included in the assessment are Language, Social, Play, Adaptive, Executive Functions, Cognition,

Motor, and Academic. The assessment is designed to be used by someone who is familiar with the child being assessed (i.e.,

parent, guardian, teacher, or clinician who has a very lengthy history of interacting with the child). The informant answers

yes-or-no questions that are linked to the over 3000 skills. Each question asks the informant whether or not the child has

each skill (e.g., Does your child spontaneously ask for a desired object when the object is not present?). Participants

caregivers were instructed to answer a question with yes only if they have observed the child execute that skill in the

course of their normal everyday life. When the assessment is used clinically, the informant also has the option to answer any

question as unsure, so that the skill can be directly probed later. For this study, only yes or no answers were included in the

data, as unsure could not be quantied for comparison with direct observation data.

Each question in the Skills Assessment is assigned an age that it generally emerges in typical child development. For each

individual participant, both questionnaire and direct probe data were collected on all of the items contained on the Skills

Assessment that were equal to or lower than the participants chronological age. For example, if a participant was ve years

old, he would receive all questions and direct observation probes for skills that emerge in typical development up to age ve.

1.4. Procedures

1.4.1. Consent

All procedures, including participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis, were approved by an Institutional

Review Board (IRB) prior to beginning the study. Once parents/caregivers showed interest in their child participating in the

study, an initial phone call was scheduled to provide more information about the study, to answer any additional questions,

and to set up an in-person meeting. During the in-person meeting, a researcher provided a verbal description of the study

purpose and procedures in addition to a more detailed written description of the study that could be read at a later time.

Additionally, a consent form was provided during the initial in-person meeting and was signed in the presence of the

researcher. Parents/caregivers were encouraged to voice any questions or concerns and were informed that they may choose

to withdraw from the study at any point in time.

1.4.2. Caregiver questionnaires

After consent was received, the researcher provided the caregiver with the printed assessment questionnaires for each

domain of the Skills Assessment. The parent was given verbal instructions to complete each question on the assessment to

the best of his or her ability by circling either Yes or No for each question. Caregivers were encouraged to answer every

question based on their current knowledge of their childs abilities and to not leave any questions blank, if possible.

1.4.3. Direct observation probes

Prior to beginning probe sessions, the researcher would select a few preferred items to use during the session. Differential

consequences were not provided for responding to any probe, in order to avoid affecting probe results. In order to make

probe sessions as fun as possible for participants, preferred items were made available after every 510 completed probes for

12 min, regardless of participant responses to probes. Researchers consequated all participant responses to probes by

saying, Okay, in a neutral tone and then presented the next probe.

1.5. Interobserver agreement

Trained secondary independent observers were available to collect interobserver agreement (IOA) data for 35

participants. IOA was collected on 43.3% (15,858) of all probes. IOA was calculated on a trial-by-trial basis, by dividing the

number of trials where both data collectors scored exactly the same data by the number of trials for which two data

collectors scored data, and multiplying by 100 to yield a percentage. Mean IOA across all probes was 98.1%. Mean IOA for

individual participants ranged from 88.2% to 100%. Across participants, the percentage of probes for which IOA data were

collected ranged from 15.3% to 100%.

284

A. Persicke et al. / Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 8 (2014) 281285

2. Results

Curriculum domain scores were calculated by taking the total number of known skills and dividing this by the total

number of skills probed. The total number of skills probed per domain varied depending upon the participants age and

feasibility of probing each skill in the individual participants environment. Additionally, some participants did not receive

probes from all domains due to various reasons (e.g., reaching the maximum number of hours, change to center-based

placement, scheduling conicts). The number of probes per participant thus varied from 75 to 1256 (m = 935.1). This resulted

in a total of 36,467 individual probes conducted across all participants.

To evaluate the degree to which results of the Skills Assessment items agreed with results from the direct probes, a

Pearson product-moment correlation coefcient was calculated for each curriculum domain score. As can be seen in Table 1,

there were moderate to high correlation values between direct observation and parent-report for each domain.

3. Discussion

The results of the current study suggest that the Skills Assessment has excellent concurrent validity. These results are

encouraging for a number of reasons. First, it is important for a curriculum assessment to be valid because precious

treatment time will be wasted if an assessment produces inaccurate results. Clinicians may waste time trying to teach skills

that a child already knows or may waste time trying to teach a skill that the assessment may have inaccurately indicated he

has the prerequisite skills for. Accurate information on what a child knows and does not know is likely to help treatment be

more individualized, more targeted, and more efcient.

An advantage of indirect assessments is they require signicantly less time to administer than do direct observations. This

allows clinicians to spend more time on treatment planning or exploring the nuance of particular skills through direct

observation. Further, it is worth noting that in this study the questions were completed by the parent or guardian. This is a

signicant contribution in that it frees the clinician to focus their time on treatment. Requiring less of the clinicians time for

assessment may have the added benets of improving the overall efciency of treatment and reducing costs.

An additional consideration is that the assessment evaluated in this study is web-based, so it may contribute to

expanding access to research-based information on ASD treatment to remote and underserved regions. The use of web-based

treatment resources may increase efciency by allowing a higher percentage of in-person treatment time to be spent on

treatment rather than assessment and curriculum management.

Finally, as noted by Gould et al. (2011), there is a general lack of psychometric evaluation of assessments that are

commonly used in ABA treatment for ASD. To our knowledge, this is the rst study to document the validity of a

comprehensive curriculum assessment for ASD treatment. It may not be surprising that few or no existing assessments for

ASD treatment planning have been subjected to psychometric evaluation. Curricula for treating children with autism are

often developed by researchers and practitioners in the eld of ABA and there is a strong tradition of direct assessment in the

eld. Indeed, virtually none of the tools developed by ABA practitioners have been subjected to rigorous psychometric

research. Part of this may be due simply to the fact that psychometric research is not an area of expertise for the vast majority

of ABA researchers. It may also be due to a perception that such research is not necessary because their tools are assumed to

be effective without them. In many simpler cases, this may seem reasonable. For example, if you want to know if a child can

ride a bike, then just give him a bike and ask him to do it. No amount of psychometric research is going to make this direct

interaction more or less valid than it already is. However, the reality of ASD skills assessment is far more complicated.

One objection to the current study is in the use of indirect assessments, per se. It is already well-accepted within the

applied behavior analytic literature that direct observation is preferable over indirect assessment, so one might argue that

establishing the validity of a particular indirect assessment is not a worthy endeavor because one should simply use direct

assessment instead. However, it may also be worth noting that indirect assessment can sometimes be more accurate than

direct observation. In order for direct assessment to be accurate, one must observe a sample of the behavior that is

representative of the real status of the behavior. It is not always obvious how to determine how large a sample this is, for any

particular skill or for any particular child. And the size of the sample that one observes is affected by several things,

including the number of times the behavior occurs, the number of opportunities there were for it to occur, the duration of

Table 1

Number of participants probed and Pearson product-moment correlation coefcients for each curriculum domain.

Curriculum

Correlation

Academic

Adaptive

Cognition

Executive function

Language

Motor

Play

Social

37

31

35

34

34

34

33

35

0.949*

0.646*

0.851*

0.665*

0.954*

0.747*

0.924*

0.738*

* p < 0.001.

A. Persicke et al. / Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 8 (2014) 281285

285

time one observes for, and the number and variety of settings one observes in. For example, if one wants to probe whether a

child can put on his shoes when asked to, how many times should one ask the child to do it? On how many different days?

With how many different kinds of shoes? And how many different people should ask him to do it? Variability is a

fundamental feature of behavior and it is therefore expected that one or two probes of a particular skill may not represent

reality. A child may be having a particularly bad" or "good" day. She may have not been attending when the skill was probed.

The many variables that affect the accuracy of any particular small sample of direct observation can be listed ad nauseam. For

some children and with some skills parent recall across many different days and settings may actually be more accurate than

a very limited number of direct probes. Especially in the case of reactivity to new observers, what the clinician observes can

sometimes be less representative of reality than what the parent reports.

Nevertheless, we would argue that, in cases where resources allow for direct probing of skills, that method should be

attempted. For example, if a childs treatment program consisted only of a focused intervention for teaching basic functional

communication skills, and the child was only two years old, then the number of skills that the clinician would need to

directly observe may well be manageable. However, the most scientically supported treatment for children with autism is

comprehensive early intensive behavioral intervention, meaning that every area of skill decit must be addressed. In the case

of a child who is ve years old, the clinician may need to directly observe and probe many hundreds, perhaps a thousand

skills something akin to what was done in the current study to collect the direct observation data. This process required up

to 30 h per child to complete and that was with trained researchers who already possessed all the materials and datasheets

required. Few children with autism have the luxury of a treatment team with 30 or more hours that they can dedicate purely

to assessing current skill levels at the outset of treatment. In most EIBI programs, there simply is not enough time to directly

assess every skill that should be assessed. The only alternatives are then to ignore a substantial portion of child development

and directly assess only the skills which the clinician believes to be particularly important (something that is likely

commonplace in current clinical practice) or to use indirect assessment in order to achieve a more comprehensive

assessment.

It may also be worth mentioning that the simple reality of autism treatment today is that, in most settings, direct probing

of all the skills children with ASD need to learn is not feasible. The vast majority of staff in special education settings do not

have the training nor the time to do a comprehensive probe of every skill that would need to be evaluated. Staff in welltrained ABA settings may indeed have the expertise required to complete such a task but few if any have the time. Put simply,

comprehensive direct assessment of everything a child with ASD needs to learn is just not going to happen on anything

approaching a large scale.

Perhaps the most judicious approach is to start with a truly comprehensive indirect assessment, such as that found in

Skills, and then to supplement it by implementing brief direct probes for particular skills which are going to be targeted soon.

In essence, such an approach would be akin to conducting ones own mini validation study with each individual skill before

teaching it with each individual child. For example, if the comprehensive indirect assessment produced a list of 200 ageappropriate skills that a child does not already possess, then the clinician might start by prioritizing the top 15, in terms of

which are more fundamental, which have prerequisite skills already in place, and so on. Then the clinician might directly

probe several examples of those 15 skills across a few environments and people. These direct observation data would then

help conrm the results of the indirect assessment for that particular child. If the child does the skill when directly probed, it

may not need to be taught. If the child does not demonstrate the skill, then it is included in her treatment program. This

process can then be repeated once or twice per month, as the child ages and gains new skills, thereby ensuring that the

treatment program always addresses the full range of skills the child may need (because it is based on the comprehensive

indirect assessment) but is also based on accurate assessment information, because that information is directly conrmed

via direct observation. This model may represent an effective marriage between the efciency and comprehensiveness of

indirect assessment with the reliability and accuracy of direct assessment.

References

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. (1999). Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children, adolescents, and adults with

autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 32S54S.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Gould, E., Dixon, D. R., Najdowski, A. C., Smith, M. N., & Tarbox, J. (2011). A review of assessments for determining the content of early intensive behavioral

intervention programs for autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(3), 9901002.

Hancock, M. A., Cautilli, J. D., Rosenwasser, B., & Clark, K. (2000). Four tactics for improving behavior analytic services. Behavior Analyst Today, 1, 3538.

Lovaas, O. I. (2003). Teaching individuals with developmental delays: Basic intervention techniques. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Love, J. R., Carr, J. E., Almason, S. M., & Petursdottir, A. I. (2009). Early and intensive behavioral intervention for autism: A survey of clinical practices. Research in

Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 421428.

Matson, J. L. (2007). Determining treatment outcome in early intervention programs for autism spectrum disorders: A critical analysis of measurement issues in

learning based interventions. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28, 207218.

Matson, J. L., & Smith, K. R. M. (2008). Current status of intensive behavioral interventions for young children with autism and PDD-NOS. Research in Autism

Spectrum Disorders, 2, 6074.

Matson, J. L., & Vollmer, T. (1995). Questions about behavioral function (QABF). Baton Rouge: Scientic.

Sigafoos, J., Schlosser, R. W., Green, V. A., OReilly, M., & Lancioni, G. E. (2008). Communication and social skills assessment. In J. L. Matson (Ed.), Clinical assessment

and intervention for autism spectrum disorders (pp. 165192). Burlington, MA: Academic Press.

Sparrow, S. S., Cicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. A. (2005). Vineland adaptive behavior scales, survey forms manual (2nd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

You might also like

- Therapist's Guide to Pediatric Affect and Behavior RegulationFrom EverandTherapist's Guide to Pediatric Affect and Behavior RegulationNo ratings yet

- S A S D R: Ummary of Utism Pectrum Isorders EsearchDocument19 pagesS A S D R: Ummary of Utism Pectrum Isorders EsearchMike GesterNo ratings yet

- Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Shin-Yi Wang, Ying Cui, Rauno ParrilaDocument8 pagesResearch in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Shin-Yi Wang, Ying Cui, Rauno ParrilaYusrina Ayu FebryanNo ratings yet

- CoachingDocument15 pagesCoachingHec ChavezNo ratings yet

- Social Skills Assessments For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders 2165 7890.1000122Document9 pagesSocial Skills Assessments For Children With Autism Spectrum Disorders 2165 7890.1000122Shinta SeptiaNo ratings yet

- Improving Adaptive Skills in A Child With Mental Retardation: A Case StudyDocument5 pagesImproving Adaptive Skills in A Child With Mental Retardation: A Case StudySadaf SadaNo ratings yet

- Article Psicometria PDFDocument14 pagesArticle Psicometria PDFEstela RecueroNo ratings yet

- 6 - A Review On Measuring Treatment Response in Parent-Mediated Autism Early InterventionsDocument16 pages6 - A Review On Measuring Treatment Response in Parent-Mediated Autism Early InterventionsAlena CairoNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Young Children, ChallengDocument20 pagesKeywords: Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Young Children, ChallengKristin Lancaster WheelerNo ratings yet

- AutismScreen AssessDocument42 pagesAutismScreen AssessMelindaDuciagNo ratings yet

- Brainsci 10 00368 v2Document17 pagesBrainsci 10 00368 v2agathamhhNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Tools To Measure Outcomes For Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder - PubMedDocument2 pagesSystematic Review of Tools To Measure Outcomes For Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder - PubMedDaniel NovakNo ratings yet

- Social Competence and Social Skills Training and Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument11 pagesSocial Competence and Social Skills Training and Intervention For Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersbmwardNo ratings yet

- Inclusion of Toddlers - AutismDocument18 pagesInclusion of Toddlers - AutismVarvara MarkoulakiNo ratings yet

- Pone 0080247Document9 pagesPone 0080247Kurumeti Naga Surya Lakshmana KumarNo ratings yet

- Outcome of Comprehensive Psycho-Educational Interventions For Young Children With AutismDocument21 pagesOutcome of Comprehensive Psycho-Educational Interventions For Young Children With AutismMilton ObandoNo ratings yet

- Berry Et Al 2015 PATHS RCT (2 November 2015)Document59 pagesBerry Et Al 2015 PATHS RCT (2 November 2015)ceglarzsabiNo ratings yet

- Scott M. Myers, MD Et, Al (2007) in The Last 2 Decades, Research and ProgramDocument3 pagesScott M. Myers, MD Et, Al (2007) in The Last 2 Decades, Research and ProgramMariakatrinuuhNo ratings yet

- Parent Implemented Intervention Complete10 2010 PDFDocument63 pagesParent Implemented Intervention Complete10 2010 PDFVictor Martin CobosNo ratings yet

- Media On ChildrenDocument9 pagesMedia On ChildrenJmNo ratings yet

- Autism RPDocument36 pagesAutism RPJeffrey Viernes100% (1)

- ESDMDocument9 pagesESDMVictória NamurNo ratings yet

- Autism Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesAutism Literature Reviewnaneguf0nuz3100% (1)

- Evidence Base Quick Facts - Floortime 2021Document3 pagesEvidence Base Quick Facts - Floortime 2021MP MartinsNo ratings yet

- Brief Report Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of A Behavioral Intervention For Minimally Verbal Girls With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument7 pagesBrief Report Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of A Behavioral Intervention For Minimally Verbal Girls With Autism Spectrum Disordergeg25625No ratings yet

- Warren (2011) Sistematic ReviewDocument11 pagesWarren (2011) Sistematic ReviewMariaClaradeFreitasNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Review of Interventions For Autism Used in or of Relevance To Occupational TherapyDocument14 pagesEvidence-Based Review of Interventions For Autism Used in or of Relevance To Occupational TherapyVanesaNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Predictors, Moderators, and Mediators of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Outcomes For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument12 pagesA Systematic Review of Predictors, Moderators, and Mediators of Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Outcomes For Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderOrnella ThysNo ratings yet

- Idd Manuscript For Special Issue Mapss Intervention Final VersionDocument20 pagesIdd Manuscript For Special Issue Mapss Intervention Final Versionapi-436977537No ratings yet

- SynopsisDocument4 pagesSynopsisaxnoorNo ratings yet

- Final Repoet Marketing ResaerchDocument11 pagesFinal Repoet Marketing Resaerch24 HoursNo ratings yet

- Peer-Mediated Social Skills Training Program For Young Children With High-Functioning AutismDocument14 pagesPeer-Mediated Social Skills Training Program For Young Children With High-Functioning AutismPsicoterapia InfantilNo ratings yet

- Applied Examples of Screening Students at Risk of Emotional and Behavioral DisabilitiesDocument9 pagesApplied Examples of Screening Students at Risk of Emotional and Behavioral DisabilitiesMohammed Demssie MohammedNo ratings yet

- Evidence For The Reliability and Preliminary Validity of The Adult ADHD Self Report Scale v1.1 (ASRS v1.1) Screener in An Adolescent CommunityDocument9 pagesEvidence For The Reliability and Preliminary Validity of The Adult ADHD Self Report Scale v1.1 (ASRS v1.1) Screener in An Adolescent CommunityMeritxell PerezNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Autism and Early InterventionDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Autism and Early Interventiondyf0g0h0fap3100% (1)

- Cognitive Behavioral With AutismDocument15 pagesCognitive Behavioral With Autismviorika56No ratings yet

- Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Learning PotentialDocument14 pagesWisconsin Card Sorting Test Learning PotentialIngrid DíazNo ratings yet

- Autism Screen and AssessmentDocument51 pagesAutism Screen and Assessmentcynthia100% (3)

- Zheng Et Al. 2021Document16 pagesZheng Et Al. 2021JonathanNo ratings yet

- ADOS ThesisDocument44 pagesADOS Thesistelopettinilamattina0% (1)

- Evidence Based Review of Interventions For Autism Used in or of Relevance To Occupational TherapyDocument14 pagesEvidence Based Review of Interventions For Autism Used in or of Relevance To Occupational Therapyapi-308033434No ratings yet

- Ezmeci & Akman, 2023Document7 pagesEzmeci & Akman, 2023florinacretuNo ratings yet

- Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Fabrizio Stasolla, Viviana Perilli, Rita DamianiDocument8 pagesResearch in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Fabrizio Stasolla, Viviana Perilli, Rita DamianiNatalyNo ratings yet

- Behavior Assessment System For Children BascDocument83 pagesBehavior Assessment System For Children Bascroselita321100% (2)

- BookChapter MethodsOfScreeningForCoreSymptDocument18 pagesBookChapter MethodsOfScreeningForCoreSymptXavier TorresNo ratings yet

- Debodinance, E., Maljaars, J., Noens, I., & Noortgate, W. (2017)Document14 pagesDebodinance, E., Maljaars, J., Noens, I., & Noortgate, W. (2017)Carlos Henrique SantosNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of The Measurement Properties of Tools Used To Measure Behaviour Problems in Young Children With Autism - PMCDocument26 pagesSystematic Review of The Measurement Properties of Tools Used To Measure Behaviour Problems in Young Children With Autism - PMCDaniel NovakNo ratings yet

- Banda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFDocument7 pagesBanda Et Al. - 2010 - Impact of Training Peers and Children With Autism PDFMuhammad Bilal ArshadNo ratings yet

- The Early Start Denver Model A Case Study of An Innovative PracticeDocument18 pagesThe Early Start Denver Model A Case Study of An Innovative PracticeLuis SeixasNo ratings yet

- A Comparison Intensive Behavior Analytic Eclectic Treatments For Young Children AutismDocument25 pagesA Comparison Intensive Behavior Analytic Eclectic Treatments For Young Children AutismRegina TorresNo ratings yet

- Statistical Analysis of Psychological Data: A Case Study of Reactive Attachment Disorder in ChildrenDocument3 pagesStatistical Analysis of Psychological Data: A Case Study of Reactive Attachment Disorder in Childrensouvik5000No ratings yet

- Behavior Problems Among School-Aged Children With Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument30 pagesBehavior Problems Among School-Aged Children With Autism Spectrum Disorderkhappi jantaNo ratings yet

- Lybarger-Monson-Final Report Autism AdhdDocument26 pagesLybarger-Monson-Final Report Autism AdhdvirgimadridNo ratings yet

- Spectrum Disorders A Systematic Review of Vocational Interventions For Young Adults With AutismDocument10 pagesSpectrum Disorders A Systematic Review of Vocational Interventions For Young Adults With Autismapi-212231304No ratings yet

- A Study Exploring The Autism AwarenessDocument8 pagesA Study Exploring The Autism AwarenessAndrés Mauricio Diaz BenitezNo ratings yet

- Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Short Version) .Document17 pagesAlabama Parenting Questionnaire (Short Version) .DijuNo ratings yet

- Evidence Base For DIR 2020Document13 pagesEvidence Base For DIR 2020MP MartinsNo ratings yet

- Njoroge 2011Document9 pagesNjoroge 2011ccarmogarciaNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of An Organization Skills Intervention To Improve The Academic Functioning of Students With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderDocument11 pagesEfficacy of An Organization Skills Intervention To Improve The Academic Functioning of Students With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity DisorderFábio Levi FontesNo ratings yet

- Final CatDocument13 pagesFinal Catapi-293253519No ratings yet

- Outpatient Asthma Management Without Rescue BronchodilatorsDocument4 pagesOutpatient Asthma Management Without Rescue BronchodilatorsHerald Scholarly Open AccessNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Wardlaws Contemporary Nutrition A Functional Approach 5th Edition Wardlaw Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Wardlaws Contemporary Nutrition A Functional Approach 5th Edition Wardlaw Test Bank PDFamoeboid.amvis.uiem100% (9)

- Overconfidence As A Cause of Diagnostic Error in Medicine PDFDocument22 pagesOverconfidence As A Cause of Diagnostic Error in Medicine PDFIulianZaharescuNo ratings yet

- Roland Morris Disability QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesRoland Morris Disability QuestionnaireSaumya SumeshNo ratings yet

- Diare Pada BalitaDocument10 pagesDiare Pada BalitaYudha ArnandaNo ratings yet

- Chest Drains Al-WPS OfficeDocument16 pagesChest Drains Al-WPS OfficeisnainiviaNo ratings yet

- Tarea Nâ°1.es - en Derecho Civil Legalmente RubiaDocument5 pagesTarea Nâ°1.es - en Derecho Civil Legalmente RubiaMax Alva SolisNo ratings yet

- Dengue Virus: A Vexatious "RED" FeverDocument6 pagesDengue Virus: A Vexatious "RED" FeverDr. Hussain NaqviNo ratings yet

- AimDocument52 pagesAimjapneet singhNo ratings yet

- 2019 EC 006 REORGANIZING BADAC Zone - 1Document5 pages2019 EC 006 REORGANIZING BADAC Zone - 1Barangay BotongonNo ratings yet

- Tonometry and Care of Tonometers PDFDocument7 pagesTonometry and Care of Tonometers PDFAnni MuharomahNo ratings yet

- Stress and Coping Styles To StudentsDocument8 pagesStress and Coping Styles To StudentsArien Kaye VallarNo ratings yet

- Campus Advocates: United Nations Association of The USADocument10 pagesCampus Advocates: United Nations Association of The USAunausaNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment: Severity (1, 2 or 3)Document1 pageRisk Assessment: Severity (1, 2 or 3)Ulviyye ElesgerovaNo ratings yet

- Biological Basis of HomosexulaityDocument22 pagesBiological Basis of HomosexulaityDhimitri BibolliNo ratings yet

- American Soc. of Addiction Medicine Naloxone StatementDocument5 pagesAmerican Soc. of Addiction Medicine Naloxone Statementwebmaster@drugpolicy.orgNo ratings yet

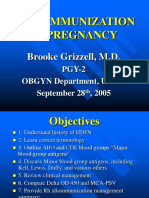

- Alloimmunization in Pregnancy: Brooke Grizzell, M.DDocument40 pagesAlloimmunization in Pregnancy: Brooke Grizzell, M.DhectorNo ratings yet

- Aldridge A Short Introduction To CounsellingDocument22 pagesAldridge A Short Introduction To Counsellingbyron chieNo ratings yet

- Wearable BiosensorDocument26 pagesWearable BiosensorViolet blossomNo ratings yet

- Planet Assist Release FormDocument2 pagesPlanet Assist Release FormJonathan W. VillacísNo ratings yet

- 03-2 Essay - Robinson CrusoeDocument15 pages03-2 Essay - Robinson CrusoeIsa RodríguezNo ratings yet

- hsg261 Health and Safety in Motor Vehicle Repair and Associated Industries PDFDocument101 pageshsg261 Health and Safety in Motor Vehicle Repair and Associated Industries PDFpranksterboyNo ratings yet

- Spoon University Nutrition GuideDocument80 pagesSpoon University Nutrition GuidermdelmandoNo ratings yet

- ABG Practice QuestionsDocument4 pagesABG Practice Questionsbbarnes0912No ratings yet

- Case Study Keme 1Document9 pagesCase Study Keme 1JhovelNo ratings yet

- PI e UREA 15Document2 pagesPI e UREA 15dewi asnaniNo ratings yet

- 2016 Article InternationalEcoHealthOneHealtDocument139 pages2016 Article InternationalEcoHealthOneHealtMauricio FemeníaNo ratings yet

- Postpartum Hemorrhage: Prevention and Treatment: Table 1Document10 pagesPostpartum Hemorrhage: Prevention and Treatment: Table 1erikafebriyanarNo ratings yet

- CH 04Document14 pagesCH 04Fernando MoralesNo ratings yet

- Cpi 260 Client Feedback ReportDocument9 pagesCpi 260 Client Feedback ReportAlexandru ConstantinNo ratings yet