Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dancing the Ramayana Across Asia

Uploaded by

Kyaw Kyaw100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

17 views2 pagesClassical dances of Asia have an important function in society - to be performed at royal courts, to celebrate the rituals of life and death. The narrative of the Ramayana travels from India to Myanmar, Thailand, laos, Indonesia, Cambodia and beyond. Three dance traditions illustrate some of the differences in style: The Bharata natyam form from india, Balinese dance from Indonesia and classical Khmer dances from Cambodia.

Original Description:

Original Title

04 Ramayana

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentClassical dances of Asia have an important function in society - to be performed at royal courts, to celebrate the rituals of life and death. The narrative of the Ramayana travels from India to Myanmar, Thailand, laos, Indonesia, Cambodia and beyond. Three dance traditions illustrate some of the differences in style: The Bharata natyam form from india, Balinese dance from Indonesia and classical Khmer dances from Cambodia.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

17 views2 pagesDancing the Ramayana Across Asia

Uploaded by

Kyaw KyawClassical dances of Asia have an important function in society - to be performed at royal courts, to celebrate the rituals of life and death. The narrative of the Ramayana travels from India to Myanmar, Thailand, laos, Indonesia, Cambodia and beyond. Three dance traditions illustrate some of the differences in style: The Bharata natyam form from india, Balinese dance from Indonesia and classical Khmer dances from Cambodia.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Dancing the

Ramayana

Classical dances of Asia have an important function

in society to be performed at royal courts, to celebrate

the rituals of life and death and to be a conduit with

the spiritual world linking the earth to the cosmos. Epic

dramas such as the Ramayana form an important part of

this continuum. The narrative of the Ramayana travels

from India to Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Indonesia,

Cambodia and beyond, and it is fascinating to explore it

through dance.

Basically, the story recounts the fortunes of Prince

Rama and his beautiful wife, Sita, who are banished from

his fathers kingdom, Kosala, and left to survive in the

forest. While in exile, they learn many of lifes important

lessons via numerous small scenes and subplots including

the kidnapping and rescue of Sita. A variety of good

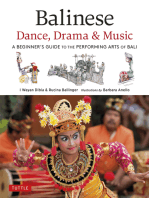

Ramayana Bali

PASSAGE April 2009

Across Asia

By Stephanie Burridge

and evil characters appear, including Ramas brother

Lakshmana, Ravana the demon king and the monkey

god Hanumaan. The story operates on multiple levels

touching on relationships, family loyalty, responsibility

and obedience, and it reveals deep moral and ethical

issues. Metaphorically, it relates to the universal aspects of

human frailty such as the struggle between good and evil,

weakness and power, lust and greed, the masculine and

the feminine and the search for the soul.

The essence of the Ramayana remains the same

although dance forms and interpretations vary across the

region. These variations include some differences in the

characterisation, the costumes, musical accompaniment

and the emphasis placed on certain parts of the story.

Three dance traditions that illustrate some of the

differences in style are the Bharata natyam form from India,

Balinese dance from Indonesia and the classical Khmer

dances from Cambodia.

The Bharata natyam is one of the eight forms of

traditional classical dance from India. This dance form

works on two expressive levels the feet pound out the

intricate rhythms of the dance and the body moves rapidly

through the space while incorporating up to 52 precise

gestures for the hands, called hastas. In Bharata natyam the

hands tell the narrative and each gesture has a meaning

that can be read both literally and metaphorically. For

instance, the lotus flower, the peacock, a bud or a leaf

are all gestures used by Sita in the Ramayana story as she

explores the forest. There are also eight emotive responses

that are embodied in these gestures and these so called

rasa include love, jealousy, serenity and happiness.

In Asia, students usually learn traditional dance

through rigorous study under the tutelage of a revered

guru or dance master. On a visit to Ubud, Bali, I watched

a master teacher pass on his wisdom to a group of 70

young dancers. Dancers

from five to eighteen

years of age assembled

silently in neat rows and

watched while, through

calm gestures, an old

man passed on the stories

of the dances. Senior

dance professionals

then demonstrated the

steps and the students

followed the intricate

pathways of the dance. Heads were poised, fingers

bent backwards into seemingly impossible positions

as their bodies danced the legong, the first dance that

the young Balinese girls learn.

For young men, participating

in the famous kecak chant dance

is an important cultural event.

Although it originated from

traditional ritualistic roots, the

present day version was created

for tourists in the 1930s by the

German painter, Walter Spies,

who greatly influenced Western

perceptions of Balinese culture

and art, in collaboration with local

danceWayan Limbak. The kecak

has become an integral part of

the Ramayana in Bali. It depicts

the scene where the monkey god

Hanumaan and Prince Rama battle

against the demon king Ravana

during their banishment to the

forest. Balinese dance incorporates

bursts of energy as the dancers

move between stillness and rapid

movements for the arms, feet and

head. Although there is the same

graceful carriage of the torso for

the women, unlike Cambodian

dancers with downcast eyes, the

Balinese performers stare out at

their audience with expressive

eyes, or wear masks.

In Cambodia, the version of the

Ramayana is known as Reamker or

Ramakerti. All the features of the

classical Khmer dance are present

in a Cambodian performance

of Reamker deep knee bends,

turned up toes, the famous flexed hands and fingers and

an innate serenity. In their entrances and exits the dancers

seem to float above the floor as they sweep in and out

with small, fast steps. There are many short scenes and the

male and female roles and real and mythical characters

interweave in the dance. The emotions of each character

are conveyed through a complexity of gestures that reveal

the stock attributes of each.

Against the backdrop of chilling statistics that 80%

to 90% of the artists in Cambodia perished during the

infamous Pol Pot regime of the 1970s, the remaining

masters feel the urgency to pass on the traditional classical

dances. Khmer Classical Dance dates from between the 1st

and 6th centuries. During the period of Angkor, dancers

of the Royal Ballet were considered servants of gods and

the link between heaven and earth. In 2003 Cambodian

classical dance was awarded World Heritage Status by

UNESCO, confirming the importance, and perhaps the

burden, of the task of preservation. Costumes had to be

remade, musical instruments sourced, dancers trained,

steps remembered and the famous characters of the

Ramayana, like Hanumaan the monkey general, had to be

brought back to life.

Ramayana Cambodia

Traditional classical dances from the Asia Pacific

region are alive with symbolism and metaphor. While

the narrative of the Ramayana is described through the

dance, a complexity of meaning is embodied within

every hand and eye gesture, every posture and sequence

of movement. The dancers are superb mimics and are

trained to perform the characters of the epics with clarity.

Knowledgeable audiences can recognise the various

attributes of each and the ability of the dancers to bring

these to life in their renditions of the roles. Following

in the steps of the Ramayana is a wonderful way to get

to know the diversity and complexity of some of the

traditional dance forms in Asia.

Stephanie Burridge grew up in Tasmania, an island as famous

for convicts and Aboriginal history as for its spectacular scenery,

ghosts, excellent wine and food. Before moving to Singapore in 2001,

she lived in Canberra, where she developed a great appreciation for

Aboriginal art and culture. She is a dancer, choreographer, teacher,

critic and writer.

Images are from Ramayana Bali and Cambodia, da:ns festival 2008.

Photos courtesy of The Esplanade Co Ltd

PASSAGE April 2009

You might also like

- Temples of the Dance: Khmer Apsara Traditions in Ancient CambodiaFrom EverandTemples of the Dance: Khmer Apsara Traditions in Ancient CambodiaNo ratings yet

- Henna ??????????: La Danseuse Du Cambodge (The Dancer from Cambodia)From EverandHenna ??????????: La Danseuse Du Cambodge (The Dancer from Cambodia)No ratings yet

- Mapeh-presentation-g8Document29 pagesMapeh-presentation-g8adambilalmuneergubaNo ratings yet

- Manhoar, Sathya & Supriya, Vandana - Yakshagana and Modern TheatreDocument11 pagesManhoar, Sathya & Supriya, Vandana - Yakshagana and Modern TheatreJAJANo ratings yet

- Apsara DanceDocument4 pagesApsara DancePhirun RaNo ratings yet

- Thumri - India's Light Classical Dance FormDocument5 pagesThumri - India's Light Classical Dance FormAzure HereNo ratings yet

- Burmese DanceDocument2 pagesBurmese DanceKo Ye50% (2)

- Khmer Apsara Dance: Cambodia's Heavenly TraditionDocument3 pagesKhmer Apsara Dance: Cambodia's Heavenly TraditionGabriela LorenaNo ratings yet

- Bali Dance and DramaDocument5 pagesBali Dance and Dramawebdesignbali100% (1)

- DanceDocument2 pagesDanceaditri anumandlaNo ratings yet

- Folk Dances of South IndiaDocument21 pagesFolk Dances of South IndiaUday Jalan100% (1)

- Dances of BangladeshDocument5 pagesDances of BangladeshAtiqur Rahman67% (3)

- Burmese 1Document11 pagesBurmese 1Mi KeeNo ratings yet

- Balinese Dance, Drama & Music: A Guide to the Performing Arts of BaliFrom EverandBalinese Dance, Drama & Music: A Guide to the Performing Arts of BaliNo ratings yet

- Manipuri Dance FormsDocument16 pagesManipuri Dance FormsSaurabh SinghNo ratings yet

- Festival and Theater Arts: China and JapanDocument34 pagesFestival and Theater Arts: China and JapanBrianne PimentelNo ratings yet

- Midterm: Pe Folk Dances in Foreign Countries: Prehistoric Times: Egyptian Tomb Paintings DepictingDocument2 pagesMidterm: Pe Folk Dances in Foreign Countries: Prehistoric Times: Egyptian Tomb Paintings DepictingMANAMTAM Ann KylieNo ratings yet

- Yakshagana and Modern TheatreDocument10 pagesYakshagana and Modern Theatreswamimanohar100% (4)

- KathakDocument3 pagesKathakkokruNo ratings yet

- Headspace 2nd YearDocument401 pagesHeadspace 2nd YearBarbara Richards100% (1)

- Desi Lens - Dance and CostumesDocument19 pagesDesi Lens - Dance and CostumesRiddhi ShahNo ratings yet

- 5 Asian DancesDocument2 pages5 Asian DancesMushy_ayaNo ratings yet

- Almost Done PeDocument7 pagesAlmost Done PeJonBelzaNo ratings yet

- Peking Opera Costumes and RolesDocument53 pagesPeking Opera Costumes and RolesRuth Aramburo83% (24)

- Indian Dance Drama Tradition: Dr. Geetha B VDocument4 pagesIndian Dance Drama Tradition: Dr. Geetha B Vprassana radhika NetiNo ratings yet

- International Folk Dance Forms and Physical Education ObjectivesDocument20 pagesInternational Folk Dance Forms and Physical Education ObjectivesKervin N. LudiviceNo ratings yet

- A Wright Brothers PresentationDocument35 pagesA Wright Brothers PresentationHilda HallNo ratings yet

- Traditional Dance in Sri Lanka NewDocument5 pagesTraditional Dance in Sri Lanka Newapi-313662154100% (1)

- 850359Document8 pages850359nanda harisahNo ratings yet

- DanceDocument21 pagesDanceJowee Anne BagonNo ratings yet

- Drametse Ngacham EdDocument4 pagesDrametse Ngacham EdzhigpNo ratings yet

- Tari Kecak: Pertunjukan Seni Khas BaliDocument10 pagesTari Kecak: Pertunjukan Seni Khas BaliwendyNo ratings yet

- Indian Classical DanceDocument5 pagesIndian Classical Dancesarora_usNo ratings yet

- Manipuri Drama's Origins in Religious Festivals and Development Over CenturiesDocument7 pagesManipuri Drama's Origins in Religious Festivals and Development Over CenturiesRajender BishtNo ratings yet

- Mapeh 4TH Quarter, Grade 8Document11 pagesMapeh 4TH Quarter, Grade 8auxiee yvieNo ratings yet

- Classical Dance of IndiaDocument3 pagesClassical Dance of IndiaUniversal ComputersNo ratings yet

- Asian FestivalsDocument9 pagesAsian FestivalsGabrielle Aoife V. MalquistoNo ratings yet

- DANCEDocument21 pagesDANCEMILDRED RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- ImadebandempaperDocument15 pagesImadebandempaperalejandroNo ratings yet

- Festivaltheaterartsofthailandchinajapanindonesia 181025063353 PDFDocument35 pagesFestivaltheaterartsofthailandchinajapanindonesia 181025063353 PDFDonato AgraveNo ratings yet

- DanceDocument41 pagesDanceElisa Del PradoNo ratings yet

- Group 3 ChinaDocument20 pagesGroup 3 ChinaRonard Lodor LladonesNo ratings yet

- Kathak - Northern India's Sparkling Dance FormDocument9 pagesKathak - Northern India's Sparkling Dance FormManu Jindal0% (1)

- Sun and MoonDocument10 pagesSun and Moonjayalfonso7204No ratings yet

- Indian Classical Dances: A Guide to the Main StylesDocument4 pagesIndian Classical Dances: A Guide to the Main StylesAkshayJhaNo ratings yet

- BSAT-ALPHA Activity Report on Fundamental Positions, Dance Forms and Countryside DancesDocument5 pagesBSAT-ALPHA Activity Report on Fundamental Positions, Dance Forms and Countryside DancesArthur SagradoNo ratings yet

- Footprints on the Silk Road: Dance in Ancient Central AsiaFrom EverandFootprints on the Silk Road: Dance in Ancient Central AsiaNo ratings yet

- Jingling Anklets: Traditional Dance Forms of Ancient ChinaFrom EverandJingling Anklets: Traditional Dance Forms of Ancient ChinaNo ratings yet

- MenoraDocument6 pagesMenoraanon-604041100% (2)

- Alice Reyes On "Rama, Hari"Document1 pageAlice Reyes On "Rama, Hari"Aaron James VelosoNo ratings yet

- Indian Art & Culture Performing Arts-Classical and Folk Dances of IndiaDocument8 pagesIndian Art & Culture Performing Arts-Classical and Folk Dances of IndiaMani TejasNo ratings yet

- On Wings of Joy: The Story of Ballet from the 16th Century to TodayFrom EverandOn Wings of Joy: The Story of Ballet from the 16th Century to TodayNo ratings yet

- DANCEDocument4 pagesDANCEhimanshiNo ratings yet

- Pangalay Dance: - Introduction To Muslim DancesDocument24 pagesPangalay Dance: - Introduction To Muslim DancesMary Clarize MercadoNo ratings yet

- Classical Dance Forms of IndiaDocument5 pagesClassical Dance Forms of IndiaAbhinav senthilNo ratings yet

- Kathakali Theatre - 105331Document11 pagesKathakali Theatre - 105331Felix JohnNo ratings yet

- Dance Forms of KeralaDocument20 pagesDance Forms of Keralahadimuhammedmc7No ratings yet

- PHILIPPINE-BALLETDocument26 pagesPHILIPPINE-BALLETKathlyn VillarNo ratings yet

- International Folk Dance and Other Dance Forms: Folk Dances in Foreign Countries-To Be AddedDocument23 pagesInternational Folk Dance and Other Dance Forms: Folk Dances in Foreign Countries-To Be AddedBataNo ratings yet

- State-wise guide to Indian folk and classical dancesDocument13 pagesState-wise guide to Indian folk and classical dancesMayur IngleNo ratings yet

- SpellsDocument16 pagesSpellsCarol Barrett100% (1)

- Man and His MusicDocument1,281 pagesMan and His MusicVishnuNo ratings yet

- You Recite The Incantation "I Am A Pure Man": Qabû, Manû or Dabābu?Document10 pagesYou Recite The Incantation "I Am A Pure Man": Qabû, Manû or Dabābu?Tarek AliNo ratings yet

- BDO Bardic Course SamplerDocument18 pagesBDO Bardic Course SamplerApostolis RountisNo ratings yet

- Theme 4 Thinkers Beliefs and Buildings HssliveDocument9 pagesTheme 4 Thinkers Beliefs and Buildings HssliveRAM RAWATNo ratings yet

- How To Create An Ancestral AltarDocument2 pagesHow To Create An Ancestral AltarEsùgbamíWilsonÌrosòOgbè100% (2)

- Athenian Festival CalendarDocument13 pagesAthenian Festival CalendarBrian SimmonsNo ratings yet

- 2016-12-25PM - The White Horse Rider Is Here To Ride You Into... - KBDocument20 pages2016-12-25PM - The White Horse Rider Is Here To Ride You Into... - KBJoe Manuel Morales MoragaNo ratings yet

- 7th Chapter 23 NotesDocument42 pages7th Chapter 23 NotesbuddylembeckNo ratings yet

- Charmed - 3x13 - Bride and Gloom - enDocument50 pagesCharmed - 3x13 - Bride and Gloom - enGa ConNo ratings yet

- Vedic Architecture: V .Surya TejaDocument26 pagesVedic Architecture: V .Surya Tejaarchitectfemil6663No ratings yet

- Ganapati Upanishad With Translation PDFDocument7 pagesGanapati Upanishad With Translation PDFGultainjeeNo ratings yet

- HOW TO DETECT AND DESTROY CURSESDocument11 pagesHOW TO DETECT AND DESTROY CURSESguy87100% (3)

- Like The Molave - Poem By/rafael Zulueta Da Costa Like The Molave - Poem By/rafael Zulueta Da CostaDocument1 pageLike The Molave - Poem By/rafael Zulueta Da Costa Like The Molave - Poem By/rafael Zulueta Da Costajessica costalesNo ratings yet

- طقوس عامDocument598 pagesطقوس عامAtheer AhmadNo ratings yet

- Japanese Mythology Quiz Reveals Fascinating Deities and Creation MythDocument16 pagesJapanese Mythology Quiz Reveals Fascinating Deities and Creation MythAlexis MechaelaNo ratings yet

- Types of MagickDocument5 pagesTypes of MagickdrjperumalNo ratings yet

- Divine MercyDocument17 pagesDivine MercyNo PatrickNo ratings yet

- PuranasDocument27 pagesPuranaskrshankar18No ratings yet

- Niruttara TantraDocument5 pagesNiruttara TantraashishpuriNo ratings yet

- Judaism 101 EbookDocument80 pagesJudaism 101 Ebookkrataios100% (1)

- A Dictionary Canarese and EnglishDocument1,053 pagesA Dictionary Canarese and EnglishPetko Nikolic VidusaNo ratings yet

- Om Canonical Form and Report or Permission For A Mixed MarriageDocument3 pagesOm Canonical Form and Report or Permission For A Mixed Marriagebn2552No ratings yet

- Prophets Prayer - Bin Baz PDFDocument8 pagesProphets Prayer - Bin Baz PDFomary hassanNo ratings yet

- Athena Patterson-Orazem Dreams in VodouDocument4 pagesAthena Patterson-Orazem Dreams in VodouRob ThuhuNo ratings yet

- Churchward-Origin and EvolutionDocument186 pagesChurchward-Origin and Evolutionwwkirk6292100% (2)

- Forms of Philippine Folk Theater Under 40 CharactersDocument28 pagesForms of Philippine Folk Theater Under 40 CharactersjericobernaNo ratings yet

- The Analects of ConfuciusDocument6 pagesThe Analects of ConfuciusWilliam Andrew Gutiera BulaqueñaNo ratings yet

- Three Hands Press: Thompson Rare BooksDocument78 pagesThree Hands Press: Thompson Rare BookshjorhrafnNo ratings yet

- AgniDocument5 pagesAgniSathyaprakash HsNo ratings yet