Professional Documents

Culture Documents

National Association of School Psychologists Position Paper On Retention

Uploaded by

Chris0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

140 views5 pageshttp://www.nasponline.org/about_nasp/pospaper_graderetent.aspx

Original Title

National Association of School Psychologists Position Paper on Retention

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documenthttp://www.nasponline.org/about_nasp/pospaper_graderetent.aspx

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

140 views5 pagesNational Association of School Psychologists Position Paper On Retention

Uploaded by

Chrishttp://www.nasponline.org/about_nasp/pospaper_graderetent.aspx

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as TXT, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 5

Position Statement on Student Grade Retention and Social Promotion

The increasing emphasis on educational standards and accountability has rekindle

d public and professional debate regarding the use of grade retention as an inte

rvention to remedy academic deficits. While some politicians, professionals, an

d organizations have called for an end to "social promotion," many states and di

stricts have established promotion standards.

Despite a century of research that fails to support the efficacy of grade retent

ion, the use of grade retention has increased over the past 25 years. It is est

imated that as many as 15% of American students are held back each year, and 30%

- 50% of students in the US are retained at least once before ninth grade. Fur

thermore, the highest retention rates are found among poor, minority, inner-city

youth. Research indicates that neither grade retention nor social promotion is

an effective strategy for improving educational success. Evidence from research

and practice highlights the importance of seeking alternatives that will promot

e social and cognitive competence of children and enhance educational outcomes.

The National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) promotes the use of inte

rventions that are evidence-based and effective and discourages the use of pract

ices which, though popular or widely accepted, are either not beneficial or are

harmful to the welfare and educational attainment of America's children and yout

h. Given the frequent use of the ineffective practice of grade retention, NASP u

rges schools and parents to seek alternatives to retention that more effectively

address the specific instructional needs of academic underachievers.

Research Findings

Findings from extensive research during the last century on the efficacy of grad

e retention warrant serious consideration. The following summarizes the prepond

erance of the evidence.

Student characteristics:

Some groups of children are more likely to be retained than others. Those at hig

hest risk for retention are male; African American or Hispanic; have a late birt

hday, delayed development and/or attention problems; live in poverty or in a sin

gle-parent household; have parents with low educational attainment; have parent

s that are less involved in their education; or have changed schools frequently.

Students who have behavior problems and display aggression or immaturity are m

ore likely to be retained. Students with reading problems, including English Lan

guage Learners, are also more likely to be retained.

Impact at the elementary school level:

. While delayed entry and readiness classes may not hurt children in the short r

un, there is no evidence of a positive effect on either long-term school achieve

ment or adjustment. Furthermore, by adolescence, these early retention practice

s are predictive of numerous health and emotional risk factors, and associated d

eleterious outcomes.

. Initial achievement gains may occur during the year the student is retained. H

owever, the consistent trend across many research studies is that achievement ga

ins decline within 2-3 years of retention, such that retained children either do

no better or perform more poorly than similar groups of promoted children. This

is true whether children are compared to same-grade peers or comparable student

s who were promoted.

. The most notable academic deficit for retained students is in reading.

. Children with the greatest number of academic, emotional, and behavioral probl

ems are most likely to experience negative consequences of retention. Subsequen

t academic and behavioral problems may result in the child being retained again.

. Retention does not appear to have a positive impact on self-esteem or overall

school adjustment; however, retention is associated with significant increases i

n behavior problems as measured by behavior rating scales completed by teachers

and parents, with problems becoming more pronounced as the child reaches adolesc

ence.

. Research examining the overall effects of 19 empirical studies conducted durin

g the 1990s compared outcomes for students who were retained and matched compari

son students who were promoted. Results indicate that grade retention had a nega

tive impact on all areas of achievement (reading, math and language) and socio-e

motional adjustment (peer relationships, self esteem, problem behaviors, and att

endance).

Impact at the secondary school level:

. Students who were retained or had delayed kindergarten entry are more likely t

o drop out of school compared to students who were never retained, even when con

trolling for achievement levels. The probability of dropping out increases with

multiple retentions. Even for single retentions, the most consistent finding fro

m decades of research is the high correlation between retention and dropping out

. A recent systematic review of research exploring dropping out of high school

indicates that grade retention is one of the most powerful predictors of high sc

hool dropout.

. Retained students have increased risks of health-compromising behaviors such a

s emotional distress, cigarette use, alcohol use, drug abuse, driving while drin

king, use of alcohol during sexual activity, early onset of sexual activity, sui

cidal intentions, and violent behaviors.

Impact in late adolescence and early adulthood:

. Prospective, longitudinal research provides evidence that retained students ha

ve a greater probability of poorer educational and employment outcomes during la

te adolescence and early adulthood. Specifically, in addition to lower levels o

f academic adjustment in eleventh grade and a greater likelihood of dropping out

of high school by age 19, retained students are also less likely to receive a d

iploma by age 20. Retained students are also less likely to be enrolled in a po

st-secondary education program and more likely to receive lower education/employ

ment status ratings, be paid less per hour, and receive poorer employment compet

ence ratings at age 20 in comparison to a group of low-achieving, promoted stude

nts. In addition, it should be noted that the low-achieving but promoted group

of students are comparable to a general population of peers on all employment ou

tcomes at age 20.

. Grade repeaters as adults are more likely to be unemployed, living on public a

ssistance or in prison than adults who did not repeat a grade.

There are multiple explanations for the negative effects associated with grade r

etention, including: 1) the absence of specific remedial strategies to enhance s

ocial or cognitive competence; 2) failure to address the risk factors associated

with retention; and 3) the consequences of being over-age for grade, which is a

ssociated with an assortment of deleterious outcomes, particularly as retained c

hildren approach middle school and puberty (stigmatizing by peers and other nega

tive experiences of grade retention may exacerbate behavioral and socio-emotiona

l adjustment problems). Evidence of the psychosocial effects of grade retention

is apparent in studies examining children's perceptions of twenty stressful life

events. Initial research two decades ago indicated that, by the time students w

ere in 6th grade, they feared retention most after the loss of a parent and goin

g blind. In 2001, 6th grade students rated grade retention as the most stressfu

l life event, followed by the loss of a parent and going blind.

Individual Considerations

The research on retention at all age levels and across studies is based on group

data. While there may be individual students who benefit from retention, no stu

dy has been able to predict accurately which children will gain from being retai

ned. Under some circumstances, retention is less likely to yield negative effect

s:

. Broadly, research indicates that students who have relatively positive self-co

ncepts; good peer relationships; social, emotional, and behavioral strengths; an

d those who have fewer achievement problems are less likely to have negative ret

ention experiences.

. Students who have difficulty in school because of lack of opportunity for inst

ruction rather than lack of ability may be helped by retention. However, this as

sumes that the lack of opportunity is related to attendance/health or mobility p

roblems that have been resolved and that the student is no more than one year ol

der than classmates.

. Retention is more likely to have benign or positive impact when students are n

ot simply held back, but receive specific remediation to address skill or behavi

oral deficits and promote achievement and social skills. However, such remediati

on is also likely to benefit students who are socially promoted.

Alternatives to Retention and Social Promotion

Both grade retention and social promotion fail to improve learning or facilitate

positive achievement and adjustment outcomes. Neither repeating a grade nor me

rely moving on to the next grade provides students with the supports they need t

o improve academic and social skills. Holding schools accountable for student p

rogress requires effective intervention strategies that provide educational oppo

rtunities and assistance to promote the social and cognitive development of stud

ents. Recognizing the cumulative developmental effects on student success at sch

ool, both early interventions and follow-up strategies are emphasized. Furtherm

ore, in acknowledging the reciprocal influence of social and cognitive skills on

academic success, effective interventions must be implemented to promote both s

ocial and cognitive competence of students. NASP encourages school districts to

consider a wide array of well-researched, evidence-based, effective, and respon

sible strategies in lieu of retention or social promotion (see Algozzine, Ysseld

yke, and Elliott, 2002 for a discussion of research-based tactics for effective

instruction; see Shinn, Walker, and Stoner, 2002 for a more extensive discussion

of interventions for academic and behavior problems).

Specifically, NASP recommends that educational professionals:

. encourage parents' involvement in their children's schools and education thro

ugh frequent contact with teachers, supervision of homework, etc.

. adopt age-appropriate and culturally sensitive instructional strategies that a

ccelerate progress in all classrooms

. emphasize the importance of early developmental programs and preschool program

s to enhance language and social skills

. incorporate systematic assessment strategies, including continuous progress mo

nitoring and formative evaluation, to enable ongoing modification of instruction

al efforts

. provide effective early reading programs

. implement effective school-based mental health programs

. use student support teams to assess and identify specific learning or behavior

problems, design interventions to address those problems, and evaluate the effi

cacy of those interventions

. use effective behavior management and cognitive behavior modification strategi

es to reduce classroom behavior problems

. provide appropriate education services for children with educational disabilit

ies, including collaboration between regular, remedial, and special education pr

ofessionals

. offer extended year, extended day , and summer school programs that focus on f

acilitating the development of academic skills

. implement tutoring and mentoring programs with peer, cross-age, or adult tutor

s

. incorporate comprehensive school-wide programs to promote the psychosocial and

academic skills of all students

. establish full-service schools to provide a community-based vehicle for the or

ganization and delivery of educational, social and health services to meet the d

iverse needs of at-risk students.

For children experiencing academic, emotional, or behavioral difficulties, neith

er grade retention nor social promotion is an effective remedy. If educational

professionals are committed to helping all children achieve academic success and

reach their full potential, we must discard ineffective practices, such as grad

e retention and social promotion, in favor of "promotion plus" specific interven

tions designed to address the factors that place students at risk for school fai

lure. NASP encourages school psychologists to actively collaborate with other p

rofessionals and parents in their school districts to address the findings of ed

ucational research, and develop and implement effective alternatives to retentio

n and social promotion. Incorporating evidence-based interventions and instruct

ional strategies into school policies and practices will enhance academic and so

cial outcomes for all students.

References

Algozzine, B., Ysseldyke, J. E., & Elliot, J. (2002). Strategies and tactics fo

r effective instruction. Longmont, CO: Sopris West.

Anderson, G. E., Jimerson, S. R., & Whipple, A.D. (2002). Student's ratings of

stressful experiences at home and school: Loss of a parent and grade retention a

s superlative stressors. Manuscript prepared for publication, available from aut

hors at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Anderson, G., Whipple, A., & Jimerson, S. (2002, November). Grade Retention: Ac

hievement and mental health outcomes. Communiqué, 31 (3), handout pages 1-3.

Dawson, P. (1998, June). A primer on student grade retention: What the research

says. Communiqué, 26 (8), 28-30.

Ferguson, P., Jimerson, S. R., & Dalton, M. (2001). Sorting out successful fail

ures: Exploratory analyses of factors associated with academic and behavioral ou

tcomes of retained students. Psychology in the Schools, 38 (4), 327-342.

Jimerson, S. R. (1999). On the failure of failure: Examining the association of

early grade retention and late adolescent education and employment outcomes. J

ournal of School Psychology, 37 (3), 243-272.

Jimerson, S. R. (2001a). Meta-analysis of grade retention research: Implications

for practice in the 21st century. School Psychology Review, 30 (3), 420-437.

Jimerson, S. R. (2001b). A synthesis of grade retention research: Looking backw

ard and moving forward. The California School Psychologist, 6, 47-59.

Jimerson, S. R., Anderson, G., & Whipple, A. (2002). Winning the battle and los

ing the war: Examining the relation between grade retention and dropping out of

high school. Psychology in the Schools, 39 (4), 441-457

Jimerson, S. R., Carlson, E., Rotert, M., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, E. (1997). A

prospective longitudinal study of the correlates and consequences of early grade

retention. Journal of School Psychology, 35 (1), 3-25.

Jimerson, S. R., Egeland, B., Sroufe, L. A., & Carlson, E. (2000). A prospect

ive longitudinal study of high school dropouts: Examining multiple predictors ac

ross development. Journal of School Psychology, 38 (6), 525-549.

Jimerson, S. R., & Kaufman, A. M. (2003). Reading, writing, and retention: A pr

imer on grade retention research. The Reading Teacher, 56 (8).

McCoy, A. R., & Reynolds, A. J. (1999). Grade retention and school performance:

An extended investigation. Journal of School Psychology, 37 (3), 273-298.

Shinn, M. R., Walker, H. M., & Stoner, G. (Eds.) (2002). Interventions for acad

emic and behavior problems II: Preventive and remedial approaches. Bethesda, MD:

National Association of School Psychologists.

Revision adopted by the NASP Delegate Assembly on April 12, 2003.

© 2003 National Association of School Psychologists, 4340 East West Highway, Su

ite 402, Bethesda MD 20814 - 301-657-0270.

You might also like

- Vizio M-Series Quantum TV Product GuideDocument17 pagesVizio M-Series Quantum TV Product GuideChrisNo ratings yet

- Vizio M Series Quantum User ManualDocument48 pagesVizio M Series Quantum User ManualChris0% (1)

- Explaining ADHD To TeachersDocument1 pageExplaining ADHD To TeachersChris100% (2)

- Reminton Trimmer 2510-769-10118-00-1Document48 pagesReminton Trimmer 2510-769-10118-00-1ChrisNo ratings yet

- Samsung Electric Range User ManualDocument180 pagesSamsung Electric Range User ManualChrisNo ratings yet

- Samsung Microwave User Manual ME21M706BAG Black OTRDocument132 pagesSamsung Microwave User Manual ME21M706BAG Black OTRChrisNo ratings yet

- GE Dishwasher User Manual GDT58CSGF2WWDocument72 pagesGE Dishwasher User Manual GDT58CSGF2WWChrisNo ratings yet

- Samsung Referigerator User ManualDocument120 pagesSamsung Referigerator User ManualChrisNo ratings yet

- Samsung Dishwasher Manual DW80K7050UG Black SS 24 Inch 3rd Rack StormwashDocument72 pagesSamsung Dishwasher Manual DW80K7050UG Black SS 24 Inch 3rd Rack StormwashChrisNo ratings yet

- Panasonic NN765XX ManualDocument60 pagesPanasonic NN765XX ManualChrisNo ratings yet

- Panasonic NN765XX ManualDocument60 pagesPanasonic NN765XX ManualChrisNo ratings yet

- Rigorous Curriculum Design Ainsworth A Four-Part Overview Part One - Seeing The Big Picture Connections FirsDocument7 pagesRigorous Curriculum Design Ainsworth A Four-Part Overview Part One - Seeing The Big Picture Connections FirsChris100% (1)

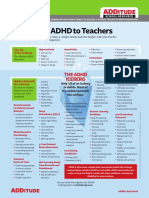

- ADD/ADHD IcebergDocument1 pageADD/ADHD IcebergChris100% (1)

- Engaging Classroom Assessments TemplateDocument26 pagesEngaging Classroom Assessments TemplateChrisNo ratings yet

- Overview To Common Formative Assessments For WMS Revised 9-9-09Document24 pagesOverview To Common Formative Assessments For WMS Revised 9-9-09ChrisNo ratings yet

- Designing Making Standards Work - ReevesDocument205 pagesDesigning Making Standards Work - ReevesChrisNo ratings yet

- Ainsworth Rigourous Curric Diagram PDFDocument1 pageAinsworth Rigourous Curric Diagram PDFChrisNo ratings yet

- Objectives Band Module 15Document2 pagesObjectives Band Module 15ChrisNo ratings yet

- Objectives Band Module 13Document2 pagesObjectives Band Module 13ChrisNo ratings yet

- Iphone User GuideDocument179 pagesIphone User GuidewiljamesclimNo ratings yet

- Band Module 10Document5 pagesBand Module 10ChrisNo ratings yet

- Samsung 55in LED TV ManualDocument181 pagesSamsung 55in LED TV ManualChrisNo ratings yet

- Objectives Band Module 01Document3 pagesObjectives Band Module 01ChrisNo ratings yet

- Yeti Microphone ManualDocument20 pagesYeti Microphone ManualChrisNo ratings yet

- Everio Manual JVCDocument84 pagesEverio Manual JVCChrisNo ratings yet

- Band Module 06Document5 pagesBand Module 06ChrisNo ratings yet

- Samsung 55in LED TV Manual Eng OnlyDocument97 pagesSamsung 55in LED TV Manual Eng OnlyChrisNo ratings yet

- Man E420 eDocument140 pagesMan E420 eckckckNo ratings yet

- Obi Device Admin GuideDocument220 pagesObi Device Admin GuideaakgsmNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Report of Inservice EducationDocument35 pagesReport of Inservice EducationAkansha JohnNo ratings yet

- FAO, WHO - Assuring Food Safety and Quality. Guidelines.2003 PDFDocument80 pagesFAO, WHO - Assuring Food Safety and Quality. Guidelines.2003 PDFAlexandra Soares100% (1)

- Laws of Malaysia: Act A1648Document42 pagesLaws of Malaysia: Act A1648ana rizanNo ratings yet

- Maximizing NICU Care Through Cost-Effective TechnologiesDocument29 pagesMaximizing NICU Care Through Cost-Effective TechnologiesVonrey Tiana73% (11)

- The Many Faces of LeadershipDocument6 pagesThe Many Faces of LeadershipbillpaparounisNo ratings yet

- Ocean Breeze Air Freshener: Safety Data SheetDocument7 pagesOcean Breeze Air Freshener: Safety Data SheetMark DunhillNo ratings yet

- Philippine eHealth Program: Enabling Digital Transformation in HealthcareDocument33 pagesPhilippine eHealth Program: Enabling Digital Transformation in HealthcareBads BrandaresNo ratings yet

- ACLS Megacode Checklist For StudentsDocument3 pagesACLS Megacode Checklist For StudentsKhrisha Anne DavilloNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Functional Pain Score by Comparing To Traditional Pain ScoresDocument7 pagesAssessment of Functional Pain Score by Comparing To Traditional Pain ScoresKepompong KupukupuNo ratings yet

- First Aid and Water SurvivalDocument18 pagesFirst Aid and Water Survivalmusubi purpleNo ratings yet

- Psychological Disorders Chapter OutlineDocument13 pagesPsychological Disorders Chapter OutlineCameron PhillipsNo ratings yet

- Agriculture, biotech, bioethics challenges of globalized food systemsDocument28 pagesAgriculture, biotech, bioethics challenges of globalized food systemsperoooNo ratings yet

- Framework Nurafni SuidDocument2 pagesFramework Nurafni SuidapninoyNo ratings yet

- BipMED Price List May 2022Document9 pagesBipMED Price List May 2022erlinNo ratings yet

- NCISM - II BAMS - AyUG-RNDocument107 pagesNCISM - II BAMS - AyUG-RN43Samprita TripathiNo ratings yet

- Blood TransfusionDocument2 pagesBlood TransfusionsenyorakathNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument6 pagesNCPNimrodNo ratings yet

- Food and Beverage Training RegulationsDocument75 pagesFood and Beverage Training Regulationsfapabear100% (1)

- Skills - Care of The Pregnant Patient ComputationsDocument5 pagesSkills - Care of The Pregnant Patient ComputationsMichelle HutamaresNo ratings yet

- PT Behavioral ProblemsDocument11 pagesPT Behavioral ProblemsAmy LalringhluaniNo ratings yet

- The Asam Clinical Practice Guideline On Alcohol-1Document74 pagesThe Asam Clinical Practice Guideline On Alcohol-1adrian prasetioNo ratings yet

- MortuaryDocument6 pagesMortuaryDr.Rajesh KamathNo ratings yet

- SEHA Blood Bank With DiagramsDocument15 pagesSEHA Blood Bank With DiagramsShahzaib HassanNo ratings yet

- Bombshell by Suzanne Somers - ExcerptDocument12 pagesBombshell by Suzanne Somers - ExcerptCrown Publishing GroupNo ratings yet

- Major Case Presentation On Acute Pulmonary Embolism WithDocument13 pagesMajor Case Presentation On Acute Pulmonary Embolism WithPratibha NatarajNo ratings yet

- Geriatrics Prescribing GuidelinessDocument27 pagesGeriatrics Prescribing GuidelinessSayli Gore100% (1)

- Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Practice EssentialsDocument28 pagesLower Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Practice EssentialsJohnPaulOliverosNo ratings yet

- Functions of Agriculture DronesDocument2 pagesFunctions of Agriculture DronesShahraz AliNo ratings yet

- Willingness To Pay For Improved Health Walk On The Accra-Aburi Mountains Walkway in GhanaDocument9 pagesWillingness To Pay For Improved Health Walk On The Accra-Aburi Mountains Walkway in GhanaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 5 6141043234522005607Document5 pages5 6141043234522005607Navin ChandarNo ratings yet