Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Tokyo Guideline TG13 PDF

Tokyo Guideline TG13 PDF

Uploaded by

Joo AnCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Tokyo Guideline TG13 PDF

Tokyo Guideline TG13 PDF

Uploaded by

Joo AnCopyright:

Available Formats

J

UOEH 35 4 : 2492572013

249

Review

Progression of Tokyo Guidelines and Japanese Guidelines for Management

of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis

Toshihiko Mayumi1*, Kazuki Someya1, Hiroki Ootubo1, Tatsuo Takama1, Takashi Kido1, Fumihiko Kamezaki1,

Masahiro Yoshida2 and Tadahiro Takada3

1

Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health,

Japan. Yahatanishi-ku Kitakyushu 807-8555, Japan

2

Clinical Research Center Kaken Hospital, International University of Health and Welfare, Koufudai Ichikawa 272-0827, Japan

3

Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Teikyo University, Kaga, Itabashi-ku 173-0003, Japan

Abstract : The Japanese Guidelines for management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis were published in 2005 as

the first practical guidelines presenting diagnostic and severity assessment criteria for these diseases. After the Japanese version, the Tokyo Guidelines (TG07) were reported in 2007 as the first international practical guidelines. There

were some differences between the two guidelines, and some weak points in TG07 were pointed out, such as low

sensitivity for diagnosis and the presence of divergence between severity assessment and clinical judgment for acute

cholangitis. Therefore, revisions were started to not only make them up to date but also concurrent with the same

diagnostic and severity assessment criteria. The Revision Committee for the revision of TG07 (TGRC) performed

validation studies of TG07 and new diagnostic and severity assessment criteria of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. These were retrospective multi-institutional studies that collected cases of acute cholangitis, cholecystitis, and

non-inflammatory biliary disease. TGRC held 35 meetings as well as international email exchanges with co-authors

abroad and held three International Meetings. Through these efforts, TG13 improved the diagnostic sensitivity for

acute cholangitis and cholecystitis, and presented criteria with extremely low false positive rates. Furthermore, severity assessment criteria adapted for clinical use, flowcharts, and many new diagnostic and therapeutic modalities

were presented. The worlds first management bundles of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis were also presented.

The revised Japanese version was published with the same content as TG13. An electronic application of TG13 that

can help to diagnose and assess the severity of these diseases using the criteria of TG13 was made for free download.

Keywords : practice guidelines, acute cholangitis, acute cholecystitis, management bundles, antibiotics.

Received July 8, 2013, accepted October 18, 2013

What are practice guidelines?

If all interventions were standardized, there would

be no need for practice guidelines, but, in any medical fields, when new diagnostic and therapeutic methods are developed some controversy over them may

occur. If there were a best practice, discrepancies in

these interventions might result in poor medical care

for patients.

Practice guidelines are made to improve patients

outcome, disseminating current good practices, but

some medical staff fear that if they did not follow the

guidelines they might be sued. Although medical staff

need to explain the contents of the guidelines to patients

*Corresponding Author: Toshihiko Mayumi, MD, Department of Emergency Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental

Health, Yahatanishi-ku, Kitakyushu, Fukuoka 807-8555, Japan. Tel:+81-93-691-7516, Fax: +81-93-691-7579, Email: mtoshi@med.uoeh-u.ac.jp

250

T Mayumi et al

and patients family, interventions should be chosen not

only by evidence, but also with the approval of the patients/family and by the medical circumstance of the

institution. Therefore, following the guidelines in any

and all situations is not necessarily the best practice.

The Japanese Guidelines for management of acute

cholangitis and cholecystitis 2003

There were no practical guidelines, evidence-basedcriteria for diagnosis, or severity assessment of treatment of acute cholecystitis or acute cholangitis before

2003. Although Charcots triad and Reynolds pentad

are well known, the full complement of symptoms and

signs described in these criteria are infrequent and not

useful in clinical management strategies [1].

In these circumstances, a project committee began to

prepare evidence-based guidelines for the management

of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. This work was

funded by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and

Welfare, in cooperation with the Japanese Society for

Abdominal Emergency Medicine, the Japan Biliary Association, and the Japanese Society of Hepato-BiliaryPancreatic Surgery. The working group, consisting of

46 experts in gastroenterology, surgery, internal medicine, emergency medicine, intensive care, and clinical

epidemiology, analyzed and examined the literature on

patients with acute cholangitis and cholecystitis in order to produce evidence-based guidelines.

There was a lack of high-level evidence in these

fields, and the working group formulated the guidelines by obtaining consensus, based on best evidence.

This work required more than 20 meetings to obtain a

consensus within the working group on each item. Following that, four forums were held to permit examination of the Guideline details in Japan to an audience in

order to collect public comments. After these efforts,

the Japanese Guidelines for management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis and diagnostic and severity assessment criteria for these diseases were published in

2005 as the first practice guidelines in the world.

Tokyo Guidelines for management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis 2007

As a next step, we attempted to make worldwide

practice guidelines for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. Since the diagnosis and management of acute

biliary infection may differ from country to country,

we appointed a publication committee and held 12

meetings to prepare draft guidelines in English. We

then had several discussions on these draft guidelines

with leading experts in the field throughout the world,

via e-mail. Finally, an International Consensus Meeting took place in Tokyo, on April 1st2nd, 2006, to

obtain international agreement on diagnostic criteria,

severity assessment, and management strategies [2].

With minor modifications after the international meeting, the Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute

cholangitis and cholecystitis (TG07) were published in

2007 as the first international practice guidelines for

these diseases [3-6]. TG07 has not only diagnostic and

severity assessment criteria, but also flowcharts, epidemiology, and several kinds of techniques of biliary

drainage and surgical methods [6-10].

Distribution of Tokyo Guidelines for management

of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis 2007

After the publication of TG07, the criteria for diagnosis and severity assessment criteria were frequently

used in new clinical studies of acute cholangitis and

cholecystitis, and citations of TG07 increased [11].

These were referred to in a text book [12, 13], in a

review in the New England Journal of Medicine [14],

and in the Guidelines for Diagnosis and management

of complicated intra-abdominal infection by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases

Society of America [15]. Also, it was reported that

compliance with the TG07 was correlated with good

outcomes of patients with acute cholangitis [16].

Japanese Guidelines 2005 (JG05) and Tokyo

Guidelines 2007 (TG07) in clinical practice

On the other hand, critical appraisal of TG07 showed

problems in applying it in clinical settings. First, the

sensitivity of acute cholangitis was low [17]. Second,

since mild and moderate acute cholangitis can be distinguished only 24 hrs after initial medical treatment in

TG07, the criteria is impractical for deciding the timing of biliary drainage [18, 19].

Progression of Tokyo Guidelines

Since the diagnostic and severity assessment criteria and the flowchart were different between the two

guidelines, these discrepancies led to confusion and

misinterpretation in Japan.

Tokyo Guidelines 2013 (TG13)

To update and correct these defects in the Japanese

Guidelines 2005 (JG05) and the Tokyo Guidelines

2007 (TG07), we set up the Tokyo Guidelines Revision Committee for the revision of TG07 (TGRC) in

June 2010 and started the validation of TG07. We also

set up new diagnostic criteria and severity assessment

criteria by retrospectively analyzing cases of acute

cholangitis and cholecystitis, including cases of noninflammatory biliary disease, collected from multiple

institutions [1, 20]. TGRC held 35 committee meetings, and three International Meetings for the Clinical Assessment and Revision of Tokyo Guidelines in

2011-2012. Through these meetings, the final draft

of the updated Tokyo Guidelines (TG13) was prepared

on the basis of evidence from retrospective multi-cen-

251

ter analyses and were published in 2013 [11]. To be

specific, discussion took place involving the revised

new diagnostic and severity assessment criteria, new

flowcharts of the management of acute cholangitis and

cholecystitis, recommended medical care for which

new evidence had been added, new recommendations

for gallbladder drainage and antimicrobial therapy,

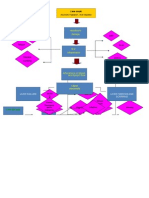

and the role of surgical intervention (Table 1, 2) (Fig.

1, 2) [21-27].

TG13 improved the diagnostic sensitivity for acute

cholangitis and cholecystitis, and presented criteria

with extremely low false positive rates adapted for

clinical practice [21, 22]. The sensitivity improved

from 82.8% (TG07) to 91.8% (TG13). While the

specificity was similar to TG07, the false positive rate

in cases of acute cholecystitis was reduced from 15.5

(TG07) to 5.9% (TG13). Furthermore, severity assessment criteria adapted for clinical use, f lowcharts,

and many new diagnostic and therapeutic modalities

were presented. Free full-text articles and a mobile application of TG13 are available via http://www.jshbps.

jp/en/guideline/tg13.html (Fig. 3).

Table 1. TG13 diagnostic criteria for acute cholangitis

A. Systemic inflammation

A-1. Fever and/or shaking chills

A-2. Laboratory data: evidence of inflammatory response

B. Cholestasis

B-1. Jaundice

B-2. Laboratory data: abnormal liver function tests

C. Imaging

C-1. Biliary dilatation

C-2. Evidence of the etiology on imaging (stricture, stone, stent etc.)

Suspected diagnosis: One item in A + one item in either B or C

Definite diagnosis: One item in A, one item in B and one item in C

Thresholds

A-1 Fever

A-2 Evidence of inflammatory response

B-1 Jaundice

B-2 Abnormal liver function tests

BT

> 38

WBC (1000/l ) < 4, or > 10

CRP (mg/dl ) 1

T-Bil 2 (g/dl)

ALP (IU) > 1.5STD

GTP (IU) > 1.5STD

AST (IU) > 1.5STD

ALT (IU) > 1.5STD

Note: A-2: Abnormal white blood cell counts, increase of serum C-reactive protein levels, and other changes indicating inf lammation.

B-2: Increased serum ALP,GTP (GGT), AST and ALT levels. Other factors which are helpful in diagnosis of acute cholangitis include

abdominal pain [right upper quadrant (RUQ) or upper abdominal] and a history of biliary disease such as gallstones, previous biliary

procedures, and placement of a biliary stent. In acute hepatitis, marked systematic inf lammatory response is observed infrequently. Virological and serological tests are required when differential diagnosis is difficult. STD: upper limit of normal value, BT: body temparature,

WBC: white blood cell count, CRP: C-reactive protein, T-Bil: toital birirubin, ALP: alkaline phosphatase, cGTP (GGT): c-glutamyltransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, Reproduced from ref. Kiriyama S et al (2013): J Hepatobiliary

Pancreat Sci 20: 24-34 [21] with permission of the Springer Science

T Mayumi et al

252

Table 2. TG13 severity assessment criteria for acute cholangitis

Grade III (Severe) acute cholangitis

Grade III acute cholangitis is defined as cholangitis that is associated with the onset of dysfunction in at least one of any of

the following organs/systems:

1. Cardiovascular dysfunction

Hypotension requiring dopamine > 5 g/kg per min, or any dose of norepinephrine

2. Neurological dysfunction

Disturbance of consciousness

3. Respiratory dysfunction

PaO2/FiO2 ratio < 300

4. Renal dysfunction

Oliguria, serum creatinine > 2.0 mg/dl

5. Hepatic dysfunction

PT-INR > 1.5

6. Hematological dysfunction

Platelet count < 100,000 / mm3

Grade II (moderate) acute cholangitis

Grade II acute cholangitis is associated with any two of the following conditions:

1. Abnormal WBC count ( > 12,000 / mm3, < 4,000 / mm3)

2. High fever ( 39C)

3. Age ( 75 years old)

4. Hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin 5 mg/dl)

5. Hypoalbuminemia ( < STD 0.7)

Grade I (mild) acute cholangitis

Grade I acute cholangitis does not meet the criteria of Grade III (severe) or Grade II (moderate) acute cholangitis at

initial diagnosis.

Notes: Early diagnosis, early biliary drainage and/or treatment for etiology, and antimicrobial administration are fundamental treatments

for acute cholangitis classified not only as Grade III (severe) and Grade II (moderate) but also Grade I (mild). Therefore, it is recommended that patients with acute cholangitis who do not respond to the initial medical treatment (general supportive care and antimicrobial

therapy) undergo early biliary drainage or treatment for etiology (see f lowchart). STD: lower limit of normal value, Reproduced from ref.

Kiriyama S et al (2013): J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 24-34 [21] with permission of the Springer Science.

Diagnosis and

Severity

Assessment by

TG13

Guidelines

Grade I

(Mild)

Treatment According to Grade, According to Response,

and According to Need for Additional Therapy

Antibiotics

and General

Supportive Care

Grade II

(Moderate)

Finish course

of antibiotics

Biliary

Drainage

Early Biliary Drainage

Antibiotics

General Supportive Care

if still needed

percutaneous treatment,

Urgent Biliary Drainage

Organ Support

Antibiotics

Fig. 1. Flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis: TG13.

for etiology

(Endoscopic treatment,

Grade III

(Severe)

Treatment

or surgery)

Performance of a blood culture should be taken into consideration before initiation of

administration of antibiotics. A bile culture should be performed during biliary drainage, : Principle

of treatment for acute cholangitis consists of antimicrobial administration and billary drainage

including treatment for etiology. For patient with choledocholithiasis, treatment for etiology might

be performed simultaneously, if possible, with biliary drainage. Reproduced from ref. Miura F et al

(2013): J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 47-54 [23] with permission of the Springer Science.

Progression of Tokyo Guidelines

Diagnosis and

Severity

Assessment by

TG13

Guidelines

Grade I

(Mild)

Treatment According to Grade and According to Response

Observation

Antibiotics

and General

Supportive Care

Grade II

(Moderate)

Antibiotics

and General

Supportive Care

Grade III

(Severe)

253

Antibiotics

and General

Organ Support

Early LC

Advanced laparoscopic

technique

available

Emergency

Surgery

Successful therapy

Failure

therapy

Urgent/early

GB drainage

Delayed/

Elective

LC

Fig. 2. Flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis: TG13.

LC: laparoscopic cholecystectomy, GB: gallbladder, : Performance of a blood culture should be

taken into consideration before initiation of administration of antibiotics, : A bile culture should

be performed during GB drainage. Reproduced from ref. Miura F et al (2013): J Hepatobiliary

Pancreat Sci 20: 47-54 [23] with permission of the Springer Science.

PDF are downloadable for free from

http://link.springer.com/journal/534/20/1/page/1 (Springer Link) or

http://www.jshbps.jp/en/guideline/tg13.html (JSHBPS HP)

Fig. 3. Download of Application and Tokyo Guidelines.

254

T Mayumi et al

Management bundles for acute cholangitis and

cholecystitis in TG13

Management bundles for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis were introduced for effective dissemination

of the guidelines recommendations for the first time in

the world (Table 3, 4) [28]. Adherence to these bundles

is a great indicator of the distribution of the guidelines,

and the correlations with adherence to these bundles

and the patients prognosis are also good indicators

of the effectiveness of the guidelines. For the conve-

Table 3. Management bundle of acute cholangitis

1. When acute cholangitis is suspected, diagnostic assessment is made using TG13 diagnostic criteria every 6-12 h

2. Abdominal X-ray (KUB) and abdominal US are carried

out, followed by CT scan, MRI, MRCP and HIDA scan

3. Severity is repeatedly assessed using severity assessment

criteria; at diagnosis, within 24 h after diagnosis, and during the time zone of 24-48 h

4. As soon as a diagnosis has been made, the initial treatment

is provided. The treatment is as follows: sufficient fluids

replacement, electrolyte compensation, and intravenous

administration of analgesics and full dose of antimicrobial

agents are provided

5. For patients with Grade I (mild), when no response to the

initial treatment is observed within 24 h, biliary tract drainage is carried out immediately

6. For patients with Grade II (moderate), biliary tract drainage is immediately performed along with the initial treatment. If early drainage cannot be performed due to the

lack of facilities or skilled personnel, transfer of the patient

is considered

7. For patients with Grade III (severe), urgent biliary tract

drainage is performed along with the initial treatment and

general supportive care. If urgent drainage cannot be performed due to the lack of facilities or skilled personnel,

transfer of the patient is considered

8. For patient with Grade III (severe), organ supports (noninvasive/invasive positive pressure ventilation, use of vasopressors and antimicrobial agents, etc.) are immediately

performed

9. Blood culture and/or bile culture is performed for Grade II

(moderate) and III (severe) patients

10. Treatment for etiology of acute cholangitis with endoscopic, percutaneous, or operative intervention is considered

once acute illness has resolved. Cholecystectomy should

be performed for cholecystolithiasis after acute cholangitis

has resolved

KUB: kidneyureterbladder, US: ultrasonography, CT: computed

tomography, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, MRCP: magnetic

resonance cholangiopancreatography, HIDA: hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid. Reproduced from ref. Okamoto K et al (2013): J

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 55-59 [28] with permission of the

Springer Science.

nience of clinicians, a checklist of the bundles has also

been prepared to confirm compliance with the bundles

of TG13.

Table 4. Management bundle of acute cholecystitis

1. When acute cholecystitis is suspected, diagnostic assessment is made using TG13 diagnostic criteria every

6-12 h

2. Abdominal US is carried out, followed by HIDA scan

and CT scan if needed to make the diagnosis

3. Severity is repeatedly assessed using severity assessment criteria; at diagnosis, within 24 h after diagnosis,

and during the time zone of 24-48 h

4. Taking into consideration that cholecystectomy is performed, as soon as a diagnosis has been made, the initial treatment takes place involving the replacement of

sufficient f luid after fasting, electrolyte compensation,

intravenous injection of analgesics and full dose antimicrobial agents

5. For patients with Grade I (mild), cholecystectomy at an

early stage within 72 h of onset of symptoms is recommended

6. If conservative treatment patients with Grade I (mild)

is selected and no response to the initial treatment is

observed within 24 h, reconsider early cholecystectomy

if still within 72 h of onset of symptoms or biliary tract

drainage

7. For patients with Grade II (moderate), perform immediate biliary drainage or drainage if no early improvement

(or cholecystectomy in experienced centers) along with

the initial treatment

8. For patients with Grade II (moderate) and III (severe) at

high surgical risk, biliary drainage is immediately carried out

9. Blood culture and/or bile culture is performed for Grade

II (moderate) and III (severe) patients

10. Among patients with Grade II (moderate), for those

with serious local complications including biliary

peritonitis, pericholecystic abscess, liver abscess or

for those with gallbladder torsion, emphysematous

cholecystitis, gangrenous cholecystitis, and purulent

cholecystitis, emergency surgery is conducted (open or

laparoscopic depending on experience) along with the

general supportive care of the patient. If surgery cannot

be performed due to the lack of facilities or skilled personnel, transfer of the patient is considered

11. For patients with Grade III (severe) with jaundice and

those in poor general conditions, emergency gallbladder

drainage is considered with initial therapy with antibiotics and general support measures. For patients who are

found to have gallbladder stones during biliary drainage, cholecystectomy is performed at after 3 month interval after the patients general conditions are improved

US: ultrasonography, CT: computed tomography, HIDA: hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid. Reproduced from ref. Okamoto K et al

(2013): J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 55-59 [28] with permission

of the Springer Science.

Progression of Tokyo Guidelines

The Japanese Guidelines 2013 (JG13)

255

cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat

Surg 14: 1-10

After finishing the final draft of TG13, a revision of

the Japanese Guidelines 2013 (JG13) was begun with

TGRC. To avoid making double standards, as between

JG05 and TG07, main schema, such as diagnostic and

severity assessment criteria, flow charts, and recommendations were set the same as TG13. Little was

modified from TG13 according to Japanese medical

situations, such as the availability of antibiotics. JG13

was published in Japanese in March 2013 as a book.

4 . Wada K, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007): Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg

14: 52-58

5 . Hirota M, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007): Diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat

Surg 14: 78-82

6 . Miura F, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007): Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholan-

Computer Application for TG13

gitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14: 27-34

To distribute TG13, we made a computer application that can help to diagnose and assess the severity

of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis using the criteria

of TG13. This Application also shows f lowcharts and

recommended antibiotics, and can be downloaded for

free (Fig. 3).

7 . Sekimoto M, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007): Need

for criteria for the diagnosis and severity assessment of

acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines.

J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14: 11-14

8 . Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007):

Techniques of biliary drainage for acute cholangitis:

Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14:

Conclusions

35-45

9 . Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007):

The Japanese and Tokyo Guidelines for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis were revised in 2013 with a

retrospective multi-center analysis of these disease

and non-inf lammatory biliary disease. These studies

and many revised international meetings lead to the

adaption of these guidelines to clinical management of

these disease. We hope that the management bundles

and computer application of these guidelines will be

distributed to medical staff and will aid the diagnosis

and severity assessment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis and improve the outcome of patients.

Techniques of biliary drainage for acute cholecystitis:

Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14:

46-51

10 . Yamashita Y, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007): Surgical treatment of patients with acute cholecystitis:

Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14:

91-97

11 . Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS et al (2013):

TG13: Updated Tokyo Guidelines for the management

of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary

Pancreat Sci 20: 1-7

12 . Cameron JL & Cameron AM (2011): Current Surgical

References

Therapy. 10th ed. Elsevier Mosby, Philadelphia, 1392 pp

13 . Dooley JS, Lok A, Burroughs A & Heathcote J (2011):

1 . Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al (2012): New

diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute

cholangitis in revised Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 19: 548-556

Sherlocks diseases of the liver and biliary system, 12th

ed. Blackwell, Hoboken, 792 pp

14 . Strasberg SM (2008): Clinical practice. Acute calculous cholecystitis. N Engl J Med 358: 2804-2811

2 . Mayumi T, Takada T, Kawarada Y et al (2007): Results

15 . Solomkin JS, Mazuski JE, Bradley JS et al (2010): Di-

of the tokyo consensus meeting Tokyo Guidelines, J

agnosis and management of complicated intra-abdom-

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 14: 114-121

inal infection in adults and children: Guidelines by the

3 . Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y et al (2007): Background: Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute

Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases

Society Of America. Clin Infect Dis 50: 133-164

T Mayumi et al

256

16 . Murata A, Matsuda S, Kuwabara K, Fujino Y, Kubo T,

TG13 guidelines for diagnosis and severity grading of

Fujimori K & Horiguchi H (2011): Evaluation of com-

acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pan-

pliance with the Tokyo Guidelines for the management

creat Sci 20: 24-34

of acute cholangitis based on the Japanese administra-

22 . Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al (2013): TG13

tive database associated with the Diagnosis Procedure

diagnostic criteria and severity grading of acute chole-

Combination system. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 18:

cystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20:

53-59

35-46

17 . Yokoe M, Takada T, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Hasegawa

23 . Miura F, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al (2013): TG13

H, Norimizu S, Hayashi K, Umemura S & Orito E

flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis and

(2011): Accuracy of the Tokyo Guidelines for the diag-

cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 47-54

nosis of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis taking into

24 . Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Takada T et al (2013): TG13

consideration the clinical practice pattern in Japan. J

antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and chole-

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 18: 250-257

cystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 60-70

18 . Fujii Y, Ohuchida J, Chijiiwa K, Yano K, Imamura N,

25 . Tsuyuguchi T, Itoi T, Takada T et al (2013): TG13 in-

Nagano M, Hiyoshi M, Otani K, Kai M & Kondo K

dications and techniques for gallbladder drainage in

(2012): Verification of Tokyo Guidelines for diagnosis

acute cholecystitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pan-

and management of acute cholangitis. J Hepatobiliary

Pancreat Sci 19: 487-491

19 . Tsuyuguchi T, Sugiyama H, Sakai Y, Nishikawa T,

dications and techniques for biliary drainage in acute

Yokosuka O, Mayumi T, Kiriyama S, Yokoe M &

cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci

Takada T (2012): Prognostic factors of acute cholan-

20: 71-80

gitis in cases managed using the Tokyo Guidelines. J

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 19: 557-565

20 . Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al (2012): New

diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute

27 . Yamashita Y, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al (2013):

TG13 surgical management of acute cholecystitis. J

Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 89-96

28 . Okamoto K, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al (2013):

cholecystitis in revised Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobi-

TG13 management bundles for acute cholangitis and

liary Pancreat Sci 19: 578-585

cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20: 55-59

21 . Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM et al (2013):

creat Sci 20: 81-88

26 . Itoi T, Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T et al (2013): TG13 in-

Progression of Tokyo Guidelines

257

Tokyo Guidelines

1 1 1 1 1 1 2

3

1

2

2005

2007 Tokyo GuidelinesTG07

TG07

TG07

3 35 TG13

TG13

J UOEH35

4

249 257

2013

You might also like

- Insuficiencia Hepatica Aguda Sobre Cronica: R1 de Gastroenterologia: Gerson Gustavo Arucutipa PinedaDocument20 pagesInsuficiencia Hepatica Aguda Sobre Cronica: R1 de Gastroenterologia: Gerson Gustavo Arucutipa PinedaGerson Arucutipa PinedaNo ratings yet

- Slide Jurnal BTKVDocument14 pagesSlide Jurnal BTKVVistaririnNo ratings yet

- Gallbladder Natural Therapy PDFDocument14 pagesGallbladder Natural Therapy PDFSoumitra Paul100% (2)

- Pathophysiology in Liver CirrhosisDocument4 pagesPathophysiology in Liver CirrhosisCyrus Ortalla RobinNo ratings yet

- Tokyo Guidelines For The Management of Acute Cholangitis and CholecystitisDocument10 pagesTokyo Guidelines For The Management of Acute Cholangitis and CholecystitisYohan YudhantoNo ratings yet

- 1 Tokyo Guidelines 2018 - Antimicrobial Therapy For Acute Cholangitis and CholecystitisDocument14 pages1 Tokyo Guidelines 2018 - Antimicrobial Therapy For Acute Cholangitis and CholecystitismvaneNo ratings yet

- CCDuodenum Periampullary Neoplasms ChuDocument68 pagesCCDuodenum Periampullary Neoplasms ChuSahirNo ratings yet

- Gastric Perforation in The Newborn: Ai-Xuan Le Holterman, M.DDocument23 pagesGastric Perforation in The Newborn: Ai-Xuan Le Holterman, M.Dpldhy2004No ratings yet

- WIFI Score For Diabetes Foot UlcerDocument17 pagesWIFI Score For Diabetes Foot Ulcertonylee24100% (1)

- Definitions, Pathophysiology, and Epidemiology of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis Tokyo GuidelinesDocument12 pagesDefinitions, Pathophysiology, and Epidemiology of Acute Cholangitis and Cholecystitis Tokyo GuidelinesGuillermo AranedaNo ratings yet

- Systemic Therapies of CRC: Johan KurniandaDocument56 pagesSystemic Therapies of CRC: Johan KurniandaANISA RACHMITA ARIANTI 2020No ratings yet

- Tokyo Guidelines 2018 Flowchart For The Management of Acute CholecystitisDocument43 pagesTokyo Guidelines 2018 Flowchart For The Management of Acute Cholecystitisfranciscomejia14835No ratings yet

- Duodenal InjuryDocument54 pagesDuodenal InjuryTony HardianNo ratings yet

- Hepatolithiasis: Alireza Sadeghi, MDDocument62 pagesHepatolithiasis: Alireza Sadeghi, MDSahirNo ratings yet

- Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Pablo Gabriel Trujillo Caraveo 299769Document51 pagesTokyo Guidelines 2018: Pablo Gabriel Trujillo Caraveo 299769Francisco Javier Espitia Romero100% (1)

- Medical Ethics Handout 2018Document37 pagesMedical Ethics Handout 2018Muhamad GaafarNo ratings yet

- Hernia World Conference ProgramDocument112 pagesHernia World Conference ProgramYovan Prakosa100% (1)

- Portal Hypertension SurgeryDocument6 pagesPortal Hypertension SurgeryjackSNMMCNo ratings yet

- Jurnal BTKV Herman 1Document11 pagesJurnal BTKV Herman 1Elyas MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Klippel Trenaunay SyndromeDocument14 pagesKlippel Trenaunay SyndromeamsirlimbongNo ratings yet

- Radiology of Gastrointestinal Tract: (GIT) Bachtiar MurtalaDocument53 pagesRadiology of Gastrointestinal Tract: (GIT) Bachtiar MurtalaMichael HusainNo ratings yet

- Principles of Minimal Invasive SurgeryDocument39 pagesPrinciples of Minimal Invasive SurgeryAvinash KannanNo ratings yet

- Biliary InjuryDocument9 pagesBiliary InjurySINAN SHAWKATNo ratings yet

- Cara Mengukur Tekanan IntrakompartemenDocument2 pagesCara Mengukur Tekanan Intrakompartemenfatimah putriNo ratings yet

- Hirschsprung DiseaseDocument20 pagesHirschsprung DiseaseIyan AsianaNo ratings yet

- Tg13: Updated Tokyo Guidelinesfor Acute CholecystitisDocument59 pagesTg13: Updated Tokyo Guidelinesfor Acute CholecystitisDeoValendraNo ratings yet

- ETHICS in SURGERY Peter Johanes ManopoDocument16 pagesETHICS in SURGERY Peter Johanes ManopoHengky TanNo ratings yet

- Colonoscopy: Dr. Aries Budianto, SPB (K) BDDocument52 pagesColonoscopy: Dr. Aries Budianto, SPB (K) BDRisal WintokoNo ratings yet

- Hernia UmbilikalisDocument16 pagesHernia UmbilikalisWibhuti EmrikoNo ratings yet

- D2 Gastrectomy: DR K Suneel Kaushik Senior Resident Surgical OncologyDocument66 pagesD2 Gastrectomy: DR K Suneel Kaushik Senior Resident Surgical OncologySuneel Kaushik KNo ratings yet

- An Updated Review of Cystic Hepatic LesionsDocument8 pagesAn Updated Review of Cystic Hepatic LesionsMayerlin CalvacheNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics Principles, 14 Januari 2018Document16 pagesMedical Ethics Principles, 14 Januari 2018Adji SuwandonoNo ratings yet

- SurgeryDocument107 pagesSurgerymesenbetbuta21No ratings yet

- DR Kiki Lukman Patofisiologi Acute CholangitisDocument36 pagesDR Kiki Lukman Patofisiologi Acute CholangitisAfkar30No ratings yet

- Cervical Spine InjuriesDocument18 pagesCervical Spine InjuriesAnnapurna DangetiNo ratings yet

- JAAOS-Management of Hemorrhage in Life-Threatening Pelvic Fracture 162Document11 pagesJAAOS-Management of Hemorrhage in Life-Threatening Pelvic Fracture 162Enny Yunita HariantiNo ratings yet

- Periampullary CarcinomaDocument35 pagesPeriampullary Carcinomaminnalesri100% (2)

- Intestinal Stomas - AKTDocument49 pagesIntestinal Stomas - AKTTammie YoungNo ratings yet

- Oeis SyndromeDocument9 pagesOeis SyndromeADEENo ratings yet

- Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Therapeutic Strategies: MT KhalfallahDocument49 pagesHilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Therapeutic Strategies: MT KhalfallahKhalfallah Mohamed TaharNo ratings yet

- Cystostomy NewDocument32 pagesCystostomy Newkuncupcupu1368No ratings yet

- Klippel Trenaunay SyndromeDocument15 pagesKlippel Trenaunay SyndromeamsirlimbongNo ratings yet

- TB and Lung CancerDocument26 pagesTB and Lung CanceraprinaaaNo ratings yet

- Colorectal CancerDocument39 pagesColorectal CancerFernando AnibanNo ratings yet

- Sejarah Dan Perkembangan Ilmu Bedah September 2017Document18 pagesSejarah Dan Perkembangan Ilmu Bedah September 2017Arief Fakhrizal100% (1)

- Perforated Gastric UlcerDocument18 pagesPerforated Gastric UlcerNorshahidah IedaNo ratings yet

- Tokyo Guidelines 2018Document115 pagesTokyo Guidelines 2018Alik Razi100% (1)

- RIZ - Enterocutaneous FistulaDocument35 pagesRIZ - Enterocutaneous FistulaAdiwirya AristiaraNo ratings yet

- RozerplastyDocument4 pagesRozerplastyLutfi Aulia RahmanNo ratings yet

- 02 Urothialisis - Prof. Doddy M SoebadiDocument27 pages02 Urothialisis - Prof. Doddy M Soebadirifqi13No ratings yet

- Carcinoma Rectum - Janak - NEWDocument74 pagesCarcinoma Rectum - Janak - NEWTowhidulIslamNo ratings yet

- 2017 Bone Modifying Agents in Met BC Slides - PpsDocument14 pages2017 Bone Modifying Agents in Met BC Slides - Ppsthanh tinh BuiNo ratings yet

- 04 Esophageal TumorsDocument36 pages04 Esophageal TumorsDetty NoviantyNo ratings yet

- Compilation Pocket Guidelines 2021Document525 pagesCompilation Pocket Guidelines 2021Radu-Constantin Vrinceanu100% (1)

- Liver Vascular Anatomy - A RefresherDocument10 pagesLiver Vascular Anatomy - A Refresherilham nugrohoNo ratings yet

- Eras For Psgs Review 2018Document18 pagesEras For Psgs Review 2018Gianina DelgadoNo ratings yet

- EBM HarmDocument24 pagesEBM HarmCOVID RSHJNo ratings yet

- Shock Management, by Ayman RawehDocument15 pagesShock Management, by Ayman RawehaymxNo ratings yet

- Colorectal Cancer 1Document71 pagesColorectal Cancer 1Anupam SisodiaNo ratings yet

- Trauma Urethra: Oleh: Stase Bedah UrologiDocument46 pagesTrauma Urethra: Oleh: Stase Bedah UrologiBrantas Pra AzariNo ratings yet

- Gastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandGastric Outlet Obstruction, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Criterios Diagnóstico para Colangitis-TokioDocument4 pagesCriterios Diagnóstico para Colangitis-TokioEduardo Martinez AvilaNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakaBella Juni SafiraNo ratings yet

- Huang ClassficationDocument5 pagesHuang ClassficationMARIO DCARLO TREJO HUAMANNo ratings yet

- Liver Cirrhosis Assignment - Kalpana JeewnaniDocument8 pagesLiver Cirrhosis Assignment - Kalpana Jeewnaniadeel arsalanNo ratings yet

- Table e - Liver Anatomy Biliary SystemDocument11 pagesTable e - Liver Anatomy Biliary Systemapi-371971600No ratings yet

- L25 CLD-2Document55 pagesL25 CLD-2S sNo ratings yet

- Kolestasis Intrahepatal Vs EkstrahepatalDocument4 pagesKolestasis Intrahepatal Vs EkstrahepatalrikarikaNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of GallbladderDocument14 pagesAnatomy of GallbladderSamridhi DawadiNo ratings yet

- Clinical Characteristics, Treatment, and Prognosis of Patients With Obstructive Jaundice in Tertiary Care Facilities: A Prospective StudyDocument4 pagesClinical Characteristics, Treatment, and Prognosis of Patients With Obstructive Jaundice in Tertiary Care Facilities: A Prospective Studyrifa iNo ratings yet

- PFD VCM (Vinyl Chloride Monomer)Document1 pagePFD VCM (Vinyl Chloride Monomer)Muhammad Hadi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Carolis Disease IDocument2 pagesSurgical Management of Carolis Disease Isuraj rajpurohitNo ratings yet

- Liver CancerDocument233 pagesLiver CancerandikhgNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat Nsaid (Kelompok 6)Document4 pagesDaftar Obat Nsaid (Kelompok 6)OktarisaNo ratings yet

- Video Conten - 2017 - Blumgart S Surgery of The Liver Biliary Tract and PancreaDocument1 pageVideo Conten - 2017 - Blumgart S Surgery of The Liver Biliary Tract and PancreaJoe JoeNo ratings yet

- What Is Your Diagnosis and Suggestions From History, Lab Investigation, and Ultrasound Scan?Document4 pagesWhat Is Your Diagnosis and Suggestions From History, Lab Investigation, and Ultrasound Scan?Dagnechew DegefuNo ratings yet

- Farmacologie Pediatrica Denumire Preparat FF, Doza Doza/Kgc Doza/Varsta ObservatiiDocument4 pagesFarmacologie Pediatrica Denumire Preparat FF, Doza Doza/Kgc Doza/Varsta ObservatiipervescudanNo ratings yet

- EHBADocument14 pagesEHBAJennifer DixonNo ratings yet

- Drug Induced Liver DisordersDocument6 pagesDrug Induced Liver DisordersGeethika GummadiNo ratings yet

- Gall Bladder Stones Surgical Treatment by Dr. Mohan SVSDocument5 pagesGall Bladder Stones Surgical Treatment by Dr. Mohan SVSFikri AlfarisyiNo ratings yet

- Sir Yahaya Memorial Hospital Birnin Kebbi: Nursing DepartmentDocument7 pagesSir Yahaya Memorial Hospital Birnin Kebbi: Nursing DepartmentyusufNo ratings yet

- The Liver and Its DisordersDocument41 pagesThe Liver and Its Disordersreuben kwotaNo ratings yet

- Hepatobiliary DiseaseDocument52 pagesHepatobiliary DiseaseMelissa Laurenshia ThenataNo ratings yet

- DR Kiki Lukman Patofisiologi Acute CholangitisDocument36 pagesDR Kiki Lukman Patofisiologi Acute CholangitisAfkar30No ratings yet

- Obstructive JaundiceDocument69 pagesObstructive JaundiceAbdirazak HassanNo ratings yet

- Cholelithiasis RLDocument29 pagesCholelithiasis RLPrincess Joanna Marie B DelfinoNo ratings yet

- What Is Fatty Liver Sign and SymptomsDocument3 pagesWhat Is Fatty Liver Sign and SymptomsIshika KohliNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis AutoinmuneDocument9 pagesHepatitis AutoinmuneJULIAN CAMILO ARIZANo ratings yet

- Organ Function Test: Assessment of Functions of The OrgansDocument39 pagesOrgan Function Test: Assessment of Functions of The OrgansSri Abinash MishraNo ratings yet