Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Indikasi Invisalign PDF

Indikasi Invisalign PDF

Uploaded by

hanataniarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Indikasi Invisalign PDF

Indikasi Invisalign PDF

Uploaded by

hanataniarCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical

Practice

Clinical Limitations of Invisalign

Contact Author

Xiem Phan, BSc, DDS; Paul H. Ling, DDS, MDS Ortho, MOrth, FDS, RCS

Dr. Ling

Email: paulling@

rcsed.ac.uk

ABSTRACT

Adult patients seeking orthodontic treatment are increasingly motivated by esthetic considerations. The majority of these patients reject wearing labial fixed appliances and

are looking instead to more esthetic treatment options, including lingual orthodontics

and Invisalign appliances. Since Align Technology introduced the Invisalign appliance in

1999 in an extensive public campaign, the appliance has gained tremendous attention

from adult patients and dental professionals. The transparency of the Invisalign appliance enhances its esthetic appeal for those adult patients who are averse to wearing

conventional labial fixed orthodontic appliances. Although guidelines about the types

of malocclusions that this technique can treat exist, few clinical studies have assessed the

effectiveness of the appliance. A few recent studies have outlined some of the limitations

associated with this technique that clinicians should recognize early before choosing

treatment options.

For citation purposes, the electronic version is the definitive version of this article: www.cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-73/issue-3/263.html

n 1945, Kesling1 introduced the tooth positioning appliance as a method of refining

the final stage of orthodontic finishing

after debanding. A positioner was a onepiece pliable rubber appliance fabricated on

the idealized wax set-ups for patients whose

basic treatment was complete. The practical

advantage of the positioner lay in its ability

to position the teeth artistically and to retain

the alignment of the teeth achieved through

basic treatment with conventional fixed appliances. Various minor tooth movements could

be incorporated into the positioner. Kesling

predicted that certain major tooth movements

could also be accomplished with a series of

positioners fabricated from sequential tooth

movements on the set-up as the treatment progressed. In 1971, Ponitz2 introduced a similar

appliance called the invisible retainer made

on a master model that prepositioned teeth

with base-plate wax. He claimed that this appliance could produce limited tooth move

ment. Sheridan and others3 later developed a

technique involving interproximal tooth reduction and progressive alignment using clear

Essix appliances. This technique was based

on Keslings proposal, but almost every tooth

movement required a new model set-up and

therefore a new set of impressions at almost

every visit, making the technique excessively

time-consuming.

In 1997 with the introduction of the

Invisalign appliance, available to orthodontists in 1999, Align Technology made Keslings

proposal much more practical. Instead of necessitating a new set-up for each new aligner,

creation of an Invisalign appliance involves

computer-aided-design and computer-aidedmanufacturing (CAD-CAM) technology,

combined with laboratory techniques, to fabricate a series of positioners (aligners) that

can move teeth in small increments of about

0.25 to 0.3 mm.

JCDA www.cda-adc.ca/jcda

April 2007, Vol. 73, No. 3

263

Ling

What is the Invisalign

Appliance?

The Invisalign appliance involves

a series of aligners made from a transparent, thin (typically less than 1 mm)

plastic material formed with CADCAM laboratory techniques. These

aligners are similar to the splints

that cover the clinical crowns and

the marginal gingiva (Fig. 1). Each

aligner is designed to move the teeth

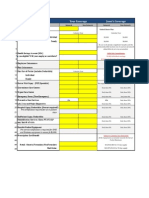

Figure 2: Finishing and detailing

Figure 1: On closer inspection, some mild

a maximum of about 0.25 to 0.3 mm

with the Invisalign appliance varies

esthetic limitations become apparent. The

in precision. Closure of extraction

Invisalign appliance is not completely invisover a 2-week period, and is worn in

spaces is often prone to excessive tipible. An inherent translucent space is visible

a specific sequence. The Invisalign apping, as seen in the lower canine and

along the incisal edges.

pliance is currently recommended for

premolar. Vertical interarch settling is

adults and for adolescents with fully

also difficult to complete.

erupted permanent teeth who meet

an acceptable standard of compliance.

Excellent compliance is mandatory

since the appliance has to be worn a

minimum of 20 to 22 hours a day and each aligner should

Current Technique

Fixed orthodontic appliances have been the backbone be worn 400 hours to be effective.

of orthodontic biomechanical technique. However, the

reluctance to wear buccal braces because of their poor

esthetic has been a driving force for the development of

alternative treatment options for the adult population.

Some current treatment options include Essix retainers,

Trutain retainers, lingual orthodontics and Invisalign

appliances.

Because of their removable nature, Essix retainers

and Trutain retainers are indicated for mild nonskeletal

malocclusions. Essix appliances have conventionally been

used as anterior retainers from cuspid to cuspid. They

are fabricated from vacuformed plastic sheets, and have

a physical memory and flexibility that allows them to

snap onto the anterior teeth, extending into gingival

undercuts. With minor modification, Essix appliances

can achieve small tooth movements, and serve as temporary bridges and bite planes.

The Invisalign appliance alone is also generally indicated for mild nonskeletal malocclusions. It was successfully used by Boyd4 in conjunction with segmental fixed

appliances, or with full fixed appliances used immediately before and after surgery for certain skeletal Class III

malocclusions.

Fixed lingual orthodontic appliances, on the other

hand, can be used for complex malocclusions. Lingual

orthodontics uses the same concept as conventional fixed

braces, but with bracket placements on the lingual rather

than the buccal surfaces of teeth. This approach improves

the esthetic look of the appliance, but has been slow to

gain popularity in North America because of insufficient

training and knowledge of the technique.

264

Indications for the Invisalign Appliance

Joffe5 suggested that the Invisalign appliance is most

successful for treating mildly malaligned malocclusions

(1 to 5 mm of crowding or spacing), deep overbite problems (e.g., Class II division 2 malocclusions) when the

overbite can be reduced by intrusion or advancement of

incisors, nonskeletally constricted arches that can be expanded with limited tipping of the teeth, and mild relapse

after fixed-appliance therapy.

Conditions that can be difficult to treat with an

Invisalign appliance or are contra-indicated altogether

include:

crowding and spacing over 5 mm

skeletal anterior-posterior discrepancies of more

than 2 mm (as measured by discrepancies in cuspid

relationships)

centric-relation and centric-occlusion discrepancies

severely rotated teeth (more than 20 degrees)

open bites (anterior and posterior) that need to be

closed

extrusion of teeth

severely tipped teeth (more than 45 degrees)

teeth with short clinical crowns

arches with multiple missing teeth.

Use of the Invisalign appliance is relatively new for

orthodontists and is still being developed. Currently, few

clinical studies and case reports have assessed the effectiveness of this technique. Although Align Technology has

suggested guidelines for its appropriate use, clinicians

have encountered numerous limitations when using the

appliance.

JCDA www.cda-adc.ca/jcda April 2007, Vol. 73, No. 3

Invisalign

Clinician Involvement

Although diagnostic preparation for treatment with

the Invisalign appliance is similar to that for treatment

with conventional fixed orthodontic appliances, clinicians play a more limited role during treatment with the

Invisalign appliance. Preparation includes initial assessment, diagnosis, treatment planning and completion of

pretreatment records (e.g., panoramic and lateral cephalometric radiographs, bite registration, photos and polyvinyl siloxane impressions), all of which must be sent to

Align Technology in California where simulated virtual

treatment is formulated by proprietary 3-dimensional

CAD-CAM technology. Clinicians then download the

virtual treatment set-up from the Internet to evaluate the

proposed final positioning of the teeth. Clinicians can request modifications at this time, but once the aligners are

made, they cannot alter the appliance during the treatment. As a consequence, clinicians must prospectively

formulate a precise treatment plan. If the results are unsatisfactory, clinicians may use auxiliary appliances (e.g.,

fixed braces) or contact Align Technology for adjustment

and fabrication of new aligners.

Compliance

Since the Invisalign appliance is removable, patient

motivation is critical to achieving the desired result. For

the appliance to be effective, patients must wear it at least

22 hours a day. They may remove it only when eating;

when drinking hot beverages that may cause warping

or staining, or beverages that contain sugar; and when

brushing and flossing. The transparency of this appliance

may increase the likelihood of its being misplaced when

it is removed. In their 1998 study comparing Essix and

Hawley retainers, Lindaurer and Shoff 6 found that one

sixth of their patients lost their appliances; the majority

of these losses were ascribable to the appliances being

clear and removable. Aligners from the Invisalign appliance have very similar properties to those of Essix

appliances.

Extraction Cases

Patients having premolar extractions may not be suitable candidates for treatment with the Invisalign appliance because the appliance cannot keep the teeth upright

during space closure (Fig. 2). Bonded restorative attachments on the buccal surfaces can assist in limited movements, but clinical results have suggested only partial

effectiveness. 5 Bollen and others7 reported excessive tipping around premolar extraction sites. They found that

only 29% of those with 2 or more premolars extracted

were able to complete space closure with the initial

aligners; none completed the overall treatment. Miller

and others, 8 in their case study of lower-incisor extrac

tion, found similar excessive tipping around extraction

sites using panoramic radiographs.

Anterior Open Bites

Treatment of anterior open bites with the Invisalign

appliance has had limited success. A few authors have

reported difficulty achieving ideal occlusion during

treatment of cases of anterior open bite. After retreatment of anterior crowding and open-bite relapse with the

Invisalign appliance, Womack and others9 found that the

position of the maxillary central incisors was superior to

that of the canines and posterior teeth. Although they

noted anterior extrusion, it was not enough to achieve

ideal overbite. In their 2003 randomized clinical trial,

Clements and others10 reported similar limitations; they

found no significant improvement in anterior open bite

after treatment.

Overbite

Although Joffe5 suggested that deep overbite problems

can be corrected with the Invisalign appliance, others

have provided evidence to the contrary. Kamatovic,11 in

a retrospective study, concluded that the Invisalign appliance did not correct overbite relationships. The peer

assessment rating (PAR) index was below 40%.

Occlusion

Many authors have suggested that removable appliances have limited potential to correct buccal malocclusions. The lack of interarch mechanics may explain this

limitation. In 2003, Clements and others10 demonstrated

that correcting buccal occlusions with appliances similar

to the Invisalign appliance was least successful; for some

patients, their buccal occlusions were worse after treatment. Djeu and others12 found that fixed appliances were

superior to the Invisalign appliance for treating buccolingual crown inclinations, occlusal contacts, occlusal

relationships, and overjet. Only 20.9% of their patients

treated with the Invisalign appliance met the predetermined passing standard, compared with the 47% of those

who had fixed appliances.

In addition, Kamatovic11 found that the Invisalign appliance in general did not reduce the PAR index and concluded that the appliance did not correct buccal segment

(antero-posterior and transverse) relationships. Vlaskalic

and Boyd13 also concluded that conventional fixed appliances could achieve better occlusal outcomes than the

Invisalign appliance.

Posterior Dental Intrusion

Because of the thickness of the Invisalign appliance, intrusion of posterior teeth is often observed.

Compensating for such intrusion must be accomplished

in the retention period when the teeth are allowed to

JCDA www.cda-adc.ca/jcda

April 2007, Vol. 73, No. 3

265

Ling

erupt freely into occlusion. Womack and others9 claimed

that intrusion could occur from 0.25 mm up to 0.5 mm.

This degree of intrusion was also confirmed by Boyd and

coworkers in their 200014 and 200213 studies.

Tooth Movement

Because it is a removable appliance, the Invisalign

appliance has very limited control over precise tooth

movements. Root paralleling during space closure after

extraction, tooth uprighting, significant tooth rotations

and tooth extrusion have been inconsistently successful.

Bollen and others 6 indicated that the Invisalign appliance yielded the most predictable results with tipping

movements.

Intermaxillary Appliances

The Invisalign appliance, because it is removable,

wraps around the teeth, which can inhibit the use of

interarch mechanics (e.g., Class II and Class III elastics).

Some clinicians have suggested using elastics on buttons

bonded to the buccal surfaces as adjuncts to tooth movement, but retention of the appliance when wearing these

elastics may be compromised. 5

Treatment Time

The clinicians treatment time can be lengthened because of the additional time required for documentation

during Invisalign case preparation. The treatment plan

must include the sequential movements for every tooth

from the beginning to the end of treatment.

If changes are needed after treatment starts, significant additional time and documentation are required

to modify the treatment plan. In addition, the lag time

between formulating a treatment plan and inserting the

appliance can be up to 2 months. This lag time can cause

further delays if the dental changes are significant because of the additional time needed for planning and

documenting the treatment again, in addition to the

extra waiting period required to make new aligners. In

their 2002 case study, Womack and others9 described

severe limitations that prevented their completion of a

patients mandibular alignment because of the delay between planning the virtual treatment and the delivery of

the appliance.

Conclusion

The Invisalign appliance may be a treatment option

for simple malocclusions, as Joffe5 suggests, but it has

some limitations. Achieving similar results to those of

more conventional fixed appliances may be difficult. The

use of the Invisalign appliance in combination with fixed

appliances has been explored to reduce the time needed

to wear fixed appliances, but may result in considerably higher professional fees overall. Conversely, the

266

Invisalign appliance can provide an excellent esthetic

during treatment, ease of use, comfort of wear, and superior oral hygiene. 5 Additional research and refinement

of the design should allow further development of this

worthwhile treatment. a

THE AUTHORS

Dr. Phan is a general dental practitioner in Waterloo,

Ontario.

Dr. Ling is adjunct clinical professor, University of Western

Ontario, London, Ontario, and postgraduate examiner, Royal

College of Surgeons of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, U.K.

Correspondence to: Dr. Paul Ling, 89 Surrey St. E, Guelph, ON N1H 3P7.

The authors have no declared financial interests in any company manufacturing the types of products mentioned in this article.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

1. Kesling HD. The philosophy of tooth positioning appliance. Am J Orthod

1945; 31:297304.

2. Ponitz RJ. Invisible retainers. Am J Orthod 1971; 59(3):26672.

3. Sheridan JJ, LeDoux W, McMinn R. Essix retainers: fabrication and supervision for permanent retention. J Clin Orthod 1993; 27(1):3745.

4. Boyd RL. Surgical-orthodontic treatment of two skeletal Class III patients

with Invisalign and fixed appliances. J Clin Orthod 2005; 39(4):24558.

5. Joffe L. Invisalign: early experiences. J Orthod 2003; 30(4):34852.

6. Lindauer SJ, Shoff RC. Comparison of Essix and Hawley retainers. J Clin

Orthod 1998; 32(2):957.

7. Bollen AM, Huang G, King G, Hujoel P, Ma T. Activation time and

material stiffness of sequential removable orthodontic appliance. Part 1:

Ability to complete treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;

124(5):496501.

8. Miller RJ, Duong TT, Derackhshan M. Lower incisor extraction treatment

with the Invisalign system. J Clin Orthod 2002; 36(2):95102.

9. Womack WR, Ahn JH, Ammari Z, Castillo A. A new approach to correction

of crowding. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2002; 122(3):3106.

10. Clements KM, Bollen AM, Huang G, King G, Hujoel P, Ma T. Activation

time and material stiffness of sequential removable orthodontic appliance. Part 2: Dental improvements. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2003;

124(5):5028.

11. Kamatovic M. A retrospective evaluation of the effectiveness of the

Invisalign appliance using the PAR and irregularity indices [dissertation].

Toronto (Ont.): University of Toronto; 2004.

12. Djeu G, Shelton S, Maganzini A. Outcome assessment of Invisalign and

traditional orthodontic treatment compared with the American Board of

Orthodontics objective grading system. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

2005; 128(3):2928.

13. Vlaskalic V, Boyd R. Orthodontic treatment of a mildly crowded malocclusion using Invisalign system. Aust Orthod J 2002; 17(1):416.

14. Boyd RL, Miller RJ, Vlaskalic V. The Invisalign system in adult orthodontics:

mild crowding and space closure cases. J Clin Orthod 2000; 34(4):20312.

JCDA www.cda-adc.ca/jcda April 2007, Vol. 73, No. 3

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Theoretical Foundation of NursingDocument60 pagesTheoretical Foundation of NursingViea Pacaco Siva100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Form 2A. Laboratory Request and Result Form: To Be Filled Out by Health WorkerDocument1 pageForm 2A. Laboratory Request and Result Form: To Be Filled Out by Health WorkerJuvy Micutuan100% (2)

- Dosha Gati NotesDocument5 pagesDosha Gati NotesbalatnNo ratings yet

- Medical Benefits SummaryDocument1 pageMedical Benefits SummaryJanet Zimmerman McNicholNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation: Group 2Document30 pagesCase Presentation: Group 2Wendy EscalanteNo ratings yet

- Dental Assisting Course Work ReportDocument6 pagesDental Assisting Course Work Reportf5dmncxc100% (2)

- 06 Why Did You Decide To Be A DentistDocument10 pages06 Why Did You Decide To Be A Dentistangi paola puicon ruizNo ratings yet

- Survival GuideDocument4 pagesSurvival Guideeclipse1130No ratings yet

- Main EssayDocument7 pagesMain EssayKen UcheonyeNo ratings yet

- Adaptive ImmunityDocument6 pagesAdaptive ImmunityAvinash SahuNo ratings yet

- Drugs Acting On The Immune System: Retchel-Elly D. Dapli-AnDocument60 pagesDrugs Acting On The Immune System: Retchel-Elly D. Dapli-AnJoshua MendozaNo ratings yet

- NCM 119 Clinical MEDICINE WARD Activity 1 G3 BSN 4 2Document13 pagesNCM 119 Clinical MEDICINE WARD Activity 1 G3 BSN 4 2Allysa MacalinoNo ratings yet

- Imle 15.02.2016 PDFDocument70 pagesImle 15.02.2016 PDFRaZy Abo RayaNo ratings yet

- Inovasi Implementasi Puskesmas Poned Dalam Upaya A PDFDocument7 pagesInovasi Implementasi Puskesmas Poned Dalam Upaya A PDFSVJ officialNo ratings yet

- OHCEA Abstract Report PDFDocument123 pagesOHCEA Abstract Report PDFDenis Michael WamalaNo ratings yet

- CaballeroaDocument13 pagesCaballeroaapi-549069910No ratings yet

- Vas BerryDocument1 pageVas BerryNabaa AlhammadiNo ratings yet

- Cestosis y Cestodos PDFDocument14 pagesCestosis y Cestodos PDFErnesto VersailleNo ratings yet

- LSS GB SIPOC Diagram Johnson Anderson2Document2 pagesLSS GB SIPOC Diagram Johnson Anderson2Seda De DrasniaNo ratings yet

- Systemic Lupus ErythematosusDocument9 pagesSystemic Lupus ErythematosusTheeya QuigaoNo ratings yet

- Pep Certificate 1Document1 pagePep Certificate 1api-283487476No ratings yet

- W3health6 q1 Mod1of2 PersonalHealthIssuesSelf-MngtSkills v2-1Document22 pagesW3health6 q1 Mod1of2 PersonalHealthIssuesSelf-MngtSkills v2-1Rona DindangNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Developmental PsychopathologyDocument30 pagesChapter 1 Developmental PsychopathologyLAVANYA M PSYCHOLOGY-COUNSELLINGNo ratings yet

- Pe 1 CLPDocument15 pagesPe 1 CLPMary Rose FalconeNo ratings yet

- Abdominal Radical Trachelectomy: A Romanian SeriesDocument5 pagesAbdominal Radical Trachelectomy: A Romanian SeriesPanuta AndrianNo ratings yet

- Behçet DiseaseDocument17 pagesBehçet DiseasePaolo QuezonNo ratings yet

- BOS Mini ScrewsDocument2 pagesBOS Mini ScrewsWajeeha YounisNo ratings yet

- Study PlanDocument9 pagesStudy PlanHNo ratings yet

- Jamia Hamdard Hamdard Nagar, New Delhi: Application Form For Non-Academic and Technical PostsDocument5 pagesJamia Hamdard Hamdard Nagar, New Delhi: Application Form For Non-Academic and Technical PostsAnonymous e8SuLivNo ratings yet

- Decubitus Ulcer Wound Care - RefratDocument35 pagesDecubitus Ulcer Wound Care - RefratheraNo ratings yet