Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Safety Management Systems and Flight Crew Training PDF

Uploaded by

Daniel QuinnOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Safety Management Systems and Flight Crew Training PDF

Uploaded by

Daniel QuinnCopyright:

Available Formats

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES

IN AVIATION

A discussion of Flight Crew Training and the

role of Safety Management Systems in aviation

operations

Daniel Quinn z3462434

INTRODUCTION

The multitude of airline accidents in recent years have placed the spotlight onto how airlines

approach the issue of accident prevention. As technology has advanced over the years, the root of

such accidents have evolved from technical weaknesses, to causes largely preventable through

improved flight crew training and robust systematic frameworks. This report seeks to discuss the

current state of Safety Management Systems and in greater detail, risk management and flight crew

training, in relation to the topic of accident prevention.

SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS

With increasing pressure from the community for airlines to operate under a well-defined Safety

Management System (SMS), the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) has set out the

global standard for aviation management. Preceding this discussion, three key words must be

defined as set out by the Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority:

Safety: is the state in which the probability of harm to persons or property is reduced to,

and maintained at, a level which is as low as reasonably practicable (ALARP) through a

continuing process of hazard identification and reduction

Management: requires planning, sources, directing and controlling

System: a coordinated plan of procedure

Combining the three components together, the role of a SMS is to serve as an organised approach

to managing safety, including the necessary organisation structures, accountabilities, policies and

procedures. Under ICAOs framework, a SMS is scalable to any organisation size and is comprised of

four components:

SAFETY POLICY AND OBJECTIVES

The first step of SMS implementation is the to establish policies and objectives, which dictate the

intended safety outcome, the steps management are required to take to achieve them and how the

organisation as a whole will work to support such policies and objectives. As a part of this process,

key safety personnel such as a Safety Manager (to oversee and drive SMS implementation) and

Safety Committee and Action Groups (to monitor and review safety performance and outcomes)

must be appointed with well-defined accountabilities and knowledge requirements. These roles are

critical and must be appropriately suited to the size of the aviation organisation in question. In a

large organisation, an entire Safety Department with a Head of Safety Manager and several support

groups may be required, whereas a less complex organisation may only require one Safety Manager

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN AVIATION | Daniel Quinn

with one or two support groups. Ultimately, the implementation of safety policy and objectives

should define the organisations culture of safety. While one may argue that any aviation operation

would inherently uphold a culture of safety, a strict way of doing business is still necessary to

guide day-to-day actions as well as having tangible, measurable goals to work towards.

SAFETY RISK M ANAGEME NT

In achieving the aforementioned policy and objectives, an organisation must then work to identify

the relevant hazards, assess their associated risks and mitigate their potential to cause harm. The

diagram below illustrates the steps required in this process.

The collapse of effective risk assessment and management has been the root of several high profile

accidents. For example, the crash of the Air France 447 Airbus A330 over the Atlantic, which resulted

in the deaths of all 228 passengers and flight crew, was likely due to the freezing of the planes pilot

tubes (BEA, 2012). The Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA) noted that

the pilot tube failures were well known on the Airbus long-range fleet yet the significant risk of these

hazards did not appear to be recognized. Such negligence in risk management is not a rare

occurrence, as aircraft operators can often expect approximately 1,000 operational safety reports

per year, of which less than 5% would be considered anything beyond low probability of risk. The

critical, yet highly difficult, step in risk management is to correctly identify the hazards which could

cause a catastrophic outcome. Tools such as risk ratings currently exist to help categorise reported

hazards but they too, are often open to interpretation.

Another perspective from which we can examine the issue, is the to focus on the fact that there are

an overwhelming number of reports. The Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) is the governing body for

safety investigations in Australia which has a mandatory reporting requirement. All serious incidents

as defined by ICAO Annex 13 are immediately reportable to the ATSB (Office of Parliamentary

Counsel, 2003). However, several other events fall into a category called Routine Reportable,

which typically have no cause for alarm. As a result, the ATSB received approximately 15,000 reports

between 2014 15 (Australian Transport Safety Bureau, 2015), of which only approximately 0.2%

were investigated. As a result, the Australian Civil Aviation Safety Authority (ACASA) has begun

taking a greater role in the process of safety investigation as the ATSB can no longer be relied upon

to observe all hazards which warrant investigation due to the sheer number of reports. This is a

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN AVIATION | Daniel Quinn

positive step towards a more effective SMS by facilitating a more robust safety investigation

capability.

Once a risk is identified, it should be managed to the extent it is ALARP, whereby the cost of further

prevention measures be significantly larger than the subsequent increase in safety. This definition

however, is once again subjective and a misinterpretation could have far reach consequences. For

example, The American Eagle flight 4184 in 1994 crashed after ice on its right wing caused the plane

to spiral and kill all 68 people on board. In the aftermath, a whistle-blower revealed longstanding

problems with the ATR aircraft under freezing conditions. The National Transport Safety Board later

determined that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) was a direct contributor to the incident

as its aircraft icing certification requirements failed to consider the hazards to a sufficient degree

(National Transport Safety Board, 1994). It was later revealed that for thirteen years prior to this

accident, the FAA consistently fought against the NTSB on changing its icing certification

methodologies as it would be excessively penalising and economically prohibitive. In 1998, the FAA

finally implemented several proposed rules and directives which are intended to reduce icing

hazards. It is clear that the interpretation of ALARP by the FAA was clearly insufficient, and that

the potential increase in safety, in fact, far outweighed the increase in cost. Hence, diligence in

assessing the extent of risk management and agility in responding to risk assessments are critical in

the effective implementation of SMS.

SAFETY ASSURANCE AND PROMOTION

Effective SMS implementation in the long run requires ongoing and systematic monitoring of safety

performance as well as constant reviews of processes and practices. The scope and complexity of

assurance measures should be congruent with the scale of the aviation organisation, and can range

from effective hazard reporting systems to front-line supervisors who report day-to-day activities

and daily inspections of safety-critical areas. Further, the service provider should establish a formal

process to evaluate changes, whether organisational or operational, which could impact its net level

of risk. One example may be ensuring the rapid expansion of an airline does not undermine the

allocation of resources to maintaining its safety standard. In response to such changes, the

organisations SMS must be amended accordingly. Overall, this process should result in a continual

improvement of the SMS.

Once all elements of a SMS are in place, the last step is to ensure the system is thoroughly promoted

to every corner of the organisation, ensuring it reaches employees of all positions, from executive

management to engineers. A constant effort must be made to ensure the various SMS processes are

communicated, and that staff are properly trained to carry out the required tasks.

FLIGHT CREW TRAINING

In addition to a robust SMS, there is now increasing public scrutiny on flight crew training and

whether it sufficiently prepares them for catastrophic circumstances. It will also be apparent

throughout the discussion, that a well-equipped and capable flight crew should is a natural

consequence of a robust SMS. A flight crew comprises of the pilot and the cabin crew. Set out below,

are the three stages of training required to hold a commercial pilot licence.

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN AVIATION | Daniel Quinn

On the other hand, there is no official regulation with regard to cabin crew training, only

recommendations from various governing aviation bodies. Central to the recommendations is Crew

Resource Management (CRM), which has become a global standard in training programs. CRM

training was initially created for pilots but was then extended to encompass all crew members. The

concept is to enhance situational awareness, planning and decision making, communication and

teamwork skills, and stress management, in order to manage flight safety under all circumstances

(Royal Aeronautical Society, 1999).

In addition to the required training, Regulation 217 of the Civil Aviation Regulations 1988 (CAR)

requires all operating flight crew of training and checking organisations undergo two checks of a

nature to test the competency of each member every 12 months (Civil Aviation Safety Authority,

2014). There has been an increasing focus on training and checking organisations in recent years, as

accidents repeatedly appear to have been caused by pilot failure to manage basic, textbook

situations. Such examples include, the Colgan Air Bombardier Q400 at Buffalo, New York, Turkish

Airline Boeing 737- 800 at Amsterdam and the FedEx Boeing MD-11F landing accident at Narita,

Tokyo. There is an increasingly prevalent school of thought which believes pilots are no longer as

diligent or skilled in their aircraft operations in the face of increasing technological advancement and

automation. It should be apparent that the need to reinforce basic flying skills in response to the

complacency caused by automated flight decks would have been easily identified under a robust

SMS. In carrying out Safety Assurance, a diligent organisation would have presumably identified

technological advancement and automation as a material change to the airlines operating

environment and evaluated any changes to its current processes necessary to maintain its standard

of safety.

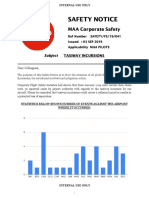

Recent commercial airline crashes such as the intentional crashing of Germanwings Flight 9525 into

the French Alps by the co-pilot in 2015 has also placed a spotlight on the emotional stability of pilots.

As illustrated by the timeline below, possible pilot suicides in airline crashes are infrequent, but still

concerning.

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN AVIATION | Daniel Quinn

While most jurisdictions require regular testing of a pilots psychological condition, increased efforts

may be necessary as part of the core training program in order to prevent incidents initiated by

unstable pilots. Note that once again, the emotional health of pilots is a hazard which should be

easily identified as part of a SMS Safety Risk Management process.

CONCLUSION

It is evident that a robust Safety Management System is a necessity in modern aviation, commercial

airlines face increasing public pressure to demonstrate their commitment so safety. Further, the

recent occurrences of accidents caused by pilot actions have also reignited debates about flight crew

training and whether it is sufficient in preventing catastrophic consequences. Ultimately however,

the successful implementation of an effective Safety Management System should work in tandem

with other aspects of the organisation such as Flight Crew Training and ensure they are adequate in

maintaining the required level of safety.

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN AVIATION | Daniel Quinn

REFERENCES

Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, (2014). SMS 1: Safety management system

basics. Canberra.

Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, (2014). SMS 2: Safety policy and objectives.

Canberra, Australia.

Australian Transport Safety Bureau, (2015). ATSB Annual Report. 2014 - 15. Canberra.

BEA, (2012). Final Report On the accident on 1st June 2009 to the Airbus A330-203 registered F-GZCP

operated by Air France flight AF 447 Rio de Janeiro - Paris. France.

Civil Aviation Safety Authority, (2014). Civil Aviation Advisory Publication. CAR 217 Flight

CrewTraining and checking organisations. Canberra.

International Civil Aviation Organization, (2013). Safety Management Manual (SMM). Montreal,

Canada.

National Transport Safety Board, (1994). AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT. IN-FLIGHT ICING ENCOUNTER

AND LOSS OF CONTROL SIMMONS AIRLINES, d.b.a. AMERICAN EAGLE FLIGHT 4184.

Washington.

Office of Parliamentary Counsel, (2003). Transport Safety Investigation Regulations 2003. Canberra.

Royal Aeronautical Society, (1999). Crew Resource Management. London.

CONTEMPORARY ISSUES IN AVIATION | Daniel Quinn

You might also like

- Airline Transport Pilot Oral Exam Guide: Comprehensive preparation for the FAA checkrideFrom EverandAirline Transport Pilot Oral Exam Guide: Comprehensive preparation for the FAA checkrideNo ratings yet

- Threat And Error Management A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionFrom EverandThreat And Error Management A Complete Guide - 2021 EditionNo ratings yet

- Air Crash Investigations - Inadvertent In-Flight Slat Deployment - The Near Crash of China Eastern Airlines Flight 583From EverandAir Crash Investigations - Inadvertent In-Flight Slat Deployment - The Near Crash of China Eastern Airlines Flight 583No ratings yet

- Flight Examiner Handbook v1Document219 pagesFlight Examiner Handbook v1Joey MarksNo ratings yet

- Q 400 SYSTEM BestDocument9 pagesQ 400 SYSTEM BestTeddy EshteNo ratings yet

- Understanding Performance Flight Testing: Kitplanes and Production AircraftFrom EverandUnderstanding Performance Flight Testing: Kitplanes and Production AircraftRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Human Performance and Limitations in AviationFrom EverandHuman Performance and Limitations in AviationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Threat and error management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionFrom EverandThreat and error management A Complete Guide - 2019 EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Safety Management Systems For Small Aviation OperationsDocument46 pagesSafety Management Systems For Small Aviation OperationsCazuto LandNo ratings yet

- Amos Form ManualDocument195 pagesAmos Form ManualIvan David Silva RodriguezNo ratings yet

- CRJ-550/700/900/1000 FMS Guide: Revision Info VOLDocument67 pagesCRJ-550/700/900/1000 FMS Guide: Revision Info VOLDaniel De AviaciónNo ratings yet

- The Grid 2: Blueprint for a New Computing InfrastructureFrom EverandThe Grid 2: Blueprint for a New Computing InfrastructureNo ratings yet

- Part 141 Student PresentationDocument48 pagesPart 141 Student PresentationRavi Ku MarNo ratings yet

- MEL M and O OnlyDocument24 pagesMEL M and O OnlymagsumNo ratings yet

- Oral and Practical Review: Reflections on the Part 147 CourseFrom EverandOral and Practical Review: Reflections on the Part 147 CourseNo ratings yet

- Safety Management Manual: Safety Is Good Business!Document5 pagesSafety Management Manual: Safety Is Good Business!Saravanan ShanmugamNo ratings yet

- Faa Airman Information Manual PDFDocument2 pagesFaa Airman Information Manual PDFRaquelNo ratings yet

- PC-12 AMM Chapter 05 31-05-2014Document310 pagesPC-12 AMM Chapter 05 31-05-2014Anonymous lcUl47JMNo ratings yet

- FAR-FC 2021: Federal Aviation Regulations for Flight CrewFrom EverandFAR-FC 2021: Federal Aviation Regulations for Flight CrewNo ratings yet

- 700 29 027 BasicDocument13 pages700 29 027 BasicHimanshu Pant100% (1)

- IATA Reference Manual For Audit Programs Ed. 8Document121 pagesIATA Reference Manual For Audit Programs Ed. 8Sandeep AroraNo ratings yet

- The Difference Between The Flapper ValvesDocument7 pagesThe Difference Between The Flapper ValvesRamez EnwesriNo ratings yet

- Annex IcaoDocument1 pageAnnex IcaoMampyu WidodoNo ratings yet

- United Balkan Airlines: Operation ManualDocument2 pagesUnited Balkan Airlines: Operation ManualÖmür EryükselNo ratings yet

- FAA Hazardous Materials Carried by Passengers and CrewDocument16 pagesFAA Hazardous Materials Carried by Passengers and Crewabelardo219No ratings yet

- STD User Approval Checklist: Appendix 18 To Chapter 9 Aircraft Operations Division Caa of LatviaDocument5 pagesSTD User Approval Checklist: Appendix 18 To Chapter 9 Aircraft Operations Division Caa of LatviaKarthikeyan RamaswamyNo ratings yet

- ATA AircraftMarshallingSignals2010Document29 pagesATA AircraftMarshallingSignals2010Santiago HidalgoNo ratings yet

- 9574 Manual On Implementation of A 300 M (1 000 FT) Vertical Separation Minimum Between FL 290 and FL 410 InclusiveDocument44 pages9574 Manual On Implementation of A 300 M (1 000 FT) Vertical Separation Minimum Between FL 290 and FL 410 InclusiveMauro SolorzanoNo ratings yet

- GaspDocument103 pagesGaspfarellano89No ratings yet

- NAT Doc 007 - V-2016-1Document207 pagesNAT Doc 007 - V-2016-1Lbrito01No ratings yet

- Cav Public Document Pilot HandbookDocument15 pagesCav Public Document Pilot HandbookAnonymous d8N4gqNo ratings yet

- 60XR RopatDocument122 pages60XR RopatFernando Julian Mamousse100% (2)

- PDFDocument62 pagesPDFSai ChNo ratings yet

- FAR-AMT 2019: Federal Aviation Regulations for Aviation Maintenance TechniciansFrom EverandFAR-AMT 2019: Federal Aviation Regulations for Aviation Maintenance TechniciansRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- 010-11 Search and RescueDocument42 pages010-11 Search and RescuePedro PinhoNo ratings yet

- Developing Advanced CRM Training, A Training Manual - Thomas L Seamster, 1998Document220 pagesDeveloping Advanced CRM Training, A Training Manual - Thomas L Seamster, 1998Endro RastadiNo ratings yet

- Week 1: Aviation LegislationDocument64 pagesWeek 1: Aviation LegislationSyamira ZakariaNo ratings yet

- IATA Training - Qualification Initiative (ITQI)Document39 pagesIATA Training - Qualification Initiative (ITQI)Jose Maria Sureda Compañ100% (1)

- Analytical Methods and ToolsDocument198 pagesAnalytical Methods and ToolsCarlos Pérez AntónNo ratings yet

- Kia e Niro English Owners ManualDocument574 pagesKia e Niro English Owners ManualdaleotarNo ratings yet

- Taxiway IncursionDocument3 pagesTaxiway IncursionDhruv Joshi100% (1)

- Fly the Airplane!: A Retired Pilot’s Guide to Fight Safety For Pilots, Present and FutureFrom EverandFly the Airplane!: A Retired Pilot’s Guide to Fight Safety For Pilots, Present and FutureNo ratings yet

- SkyWest Code of Conduct SP150Document10 pagesSkyWest Code of Conduct SP150mina catNo ratings yet

- Easa Part 145 Rev.01Document146 pagesEasa Part 145 Rev.01airsor100% (1)

- Odm 301 Rev 30Document910 pagesOdm 301 Rev 30JAVIER TIBOCHANo ratings yet

- Operations Attachment 1 - Atlas Air Interview TranscriptsDocument734 pagesOperations Attachment 1 - Atlas Air Interview TranscriptsGFNo ratings yet

- All Summer in A Day Text and Study QuestionsDocument4 pagesAll Summer in A Day Text and Study QuestionsDaniel QuinnNo ratings yet

- Probability of RuinDocument84 pagesProbability of RuinDaniel QuinnNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Stock PitchDocument13 pagesPresentation On Stock PitchDaniel QuinnNo ratings yet

- The Cosmic Engine NotesDocument3 pagesThe Cosmic Engine NotesDaniel QuinnNo ratings yet

- Structural ReliabilityDocument198 pagesStructural ReliabilityponshhhNo ratings yet

- #405 Maintenance of Emergency GeneratorDocument2 pages#405 Maintenance of Emergency GeneratorTolias EgwNo ratings yet

- Poster SIL 1Document1 pagePoster SIL 1luisbottonNo ratings yet

- MoranbahDocument143 pagesMoranbahenviroNo ratings yet

- Procedure: Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment and Risk ManagementDocument45 pagesProcedure: Hazard Identification, Risk Assessment and Risk ManagementWasim ShaikNo ratings yet

- Iec61508 Uses and AbusesDocument5 pagesIec61508 Uses and Abusesuserscribd2011No ratings yet

- L1-CHE-PRO-001 - Standard Waiver ProcedureDocument16 pagesL1-CHE-PRO-001 - Standard Waiver ProcedureCK TangNo ratings yet

- Noise PDFDocument24 pagesNoise PDFRamadan KareemNo ratings yet

- HSEIA PresentationDocument150 pagesHSEIA PresentationImranFazal100% (1)

- 6-HSE OSD 21 - The Safe Approach, Set-Up and Departure of Jack Up Rigs To Fixed InstallationsDocument9 pages6-HSE OSD 21 - The Safe Approach, Set-Up and Departure of Jack Up Rigs To Fixed InstallationsRidamrutNo ratings yet

- Semi - Sub Ballast Tank ThesisDocument110 pagesSemi - Sub Ballast Tank Thesiskiran vinjamNo ratings yet

- Good Practice Guideline The Safe Management of Small Service Vessels Used in The Offshore Wind Industry 2nd EditionDocument105 pagesGood Practice Guideline The Safe Management of Small Service Vessels Used in The Offshore Wind Industry 2nd Editionromedic36No ratings yet

- Submarine Escape PaperDocument11 pagesSubmarine Escape PaperasdalfNo ratings yet

- NORSOK Standard Z-013 PDFDocument126 pagesNORSOK Standard Z-013 PDFAlber PérezNo ratings yet

- EPRI Field Guide For Boiler Tube Failures PDFDocument2 pagesEPRI Field Guide For Boiler Tube Failures PDFandi suntoroNo ratings yet

- PR-1076 - Isolation of Process Equipment ProcedureDocument41 pagesPR-1076 - Isolation of Process Equipment Procedurevaithy1990100% (3)

- 6.1 Risk Identification - AssessmentDocument7 pages6.1 Risk Identification - Assessmentbilo1984No ratings yet

- CS 461 Assessment and Upgrading of In-Service Parapets-WebDocument97 pagesCS 461 Assessment and Upgrading of In-Service Parapets-Webantonio111aNo ratings yet

- PBS - Safety Case - ISS02 REV00 - Dec 13th 2016 - PBS-HSE-SC-001Document231 pagesPBS - Safety Case - ISS02 REV00 - Dec 13th 2016 - PBS-HSE-SC-001George Medeiros100% (4)

- Risk Assessment TrainingDocument42 pagesRisk Assessment TrainingSami Khan100% (2)

- X-Ray Safety ManualDocument34 pagesX-Ray Safety ManualAhmed AssafNo ratings yet

- Stdprod 069405Document184 pagesStdprod 069405Victor IkeNo ratings yet

- Dam Risk Management - R.stewartDocument28 pagesDam Risk Management - R.stewartJimmy Enriquez DueñasNo ratings yet

- 2010 HP&D Asia - Dam Safety During Design, Construction and Operation - BARKER PDFDocument11 pages2010 HP&D Asia - Dam Safety During Design, Construction and Operation - BARKER PDFMihai MihailescuNo ratings yet

- Modern Safety Management System & Risk Assessmentrisk Assessment MixDocument133 pagesModern Safety Management System & Risk Assessmentrisk Assessment MixNoppanun Nankongnab100% (1)

- HSE Risk ManagementDocument9 pagesHSE Risk ManagementSamuelFarfanNo ratings yet

- JOY, Jim GRIFFITHS, Derek. National Minerals Industry Safety and Health Risk Assessment Guideline. Version 3, March, MCA and MISHC, Australia, (2011), Retrieved August 2013 at Www. Pla PDFDocument164 pagesJOY, Jim GRIFFITHS, Derek. National Minerals Industry Safety and Health Risk Assessment Guideline. Version 3, March, MCA and MISHC, Australia, (2011), Retrieved August 2013 at Www. Pla PDFAender FerreiraNo ratings yet

- FPSO Inherently Safe Design ReportSCM TC110 128 018 01Document82 pagesFPSO Inherently Safe Design ReportSCM TC110 128 018 01Faridah feedausNo ratings yet

- Paper 2Document8 pagesPaper 2Nitesh Kirnake100% (1)

- IMechE Alarp-Technical-Safety-Guide - 2021Document105 pagesIMechE Alarp-Technical-Safety-Guide - 2021jesse.ipsaro-passioneNo ratings yet