Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Frege's Sharpness Requirement - by GaryKemp

Uploaded by

s_j_darcy0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views17 pagesGaryKemp on Frege's Sharpness Requirement

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentGaryKemp on Frege's Sharpness Requirement

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

10 views17 pagesFrege's Sharpness Requirement - by GaryKemp

Uploaded by

s_j_darcyGaryKemp on Frege's Sharpness Requirement

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 17

The Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 48, No. 183 April

ISSN 0031-fagy

FREGE’S SHARPNESS REQUIREMENT

By Gary Kemp

Readers of Frege could excusably reason as follows: whether or not he is

correctly described as a ‘philosopher of language’, Frege advanced a theory

of the structure and composition of thoughts, and of how those components

function in determining the truth-values of sentences which express them.

According to that theory, an atomic sentence comprising a proper name

and unary predicate is true where the name and predicate denote, respec-

tively, an object and a concept, and the object falls under the concept. But

he also stressed that there can be no such thing as a concept which is not, as

he put it, sharp: for every concept and object whatsoever, either the object

falls under the concept, or it falls under its contradictory. Thus only sent-

ences whose predicates are defined for every object whatsoever as argument

can be true. And that seems manifestly wrong.!

In what follows, I discuss two remarkable attempts, recently advanced by

Joan Weiner and Tyler Burge, to dispel the appearance of a real difficulty

on this point. The appearance, according to each, is due to the persisting

influence of more familiar but anachronistic interpretations of Frege’s work

both urge the re-interpretation of central Fregean doctrines in such a way as

I refer to the works of Frege as follows:

Grundgseze der Artonet 1 (Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1962) [Gi].

The Basic Laws of Arithmetic: Exposition ofthe System, ed, and wwans. M. Furth (Univ. of California

Press, 1964) [BL]

Begriffuchrift und andere Auftze, ed. 1. Angele (Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1964) [BE]. An

English translation is included in J. van Heijenoort (ed), From Frege to Gel: a Source Book in

Mathematical Logic (Harvard UP, 1967). References are to the section numbers

Kicine Schifen, ed. T Angele Hildesheim: Georg Olms, 1967) [A3

The Foundations of Arithmetic, trans. J-1. Austin {Northwestern Univ, Press, 1968) [F2]

Nachgelasine Schrifen, ed. H. Hermes eal, (Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 196g) [NS]

Wissenschaflcher Brfvesl, ed. G. Gabriel eal. (Hamburg: Felix Meiner, 1976) {1B}

Posthumous Wraings, ed. H Hermes et al. Univ. of Chicago Press, 1979) [PH]

Philsophical and Mathematical Correspondence, ed. H. Hermes et al. (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1980)

(AMC)

Translations fom the Philosophical Wirtings of Gatlob Frege, grd een, ed. and trans. P. Geach and M.

Black (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1980) [TPH]

Collected Papers on Mathematics, Log, and Philosophy, ed. B. McGuinness (Oxford: Basil Blackwell

1984) (CP.

i an he np tg Py al a 1 iy Rone 9 ER

FREGE'S SHARPNESS REQUIREMENT. 169

to reflect those deeper currents in Frege’s thought which, due to their

subtlety and disaffinity from the outlook of subsequent analytical philo~

sophy, have escaped its notice. The warning against anachronism is well

taken; but I shall contest these interpretations, partly on the grounds that the

deeper subtleties these authors adduce can only wilfully be read into Frege’s

work, and partly on the grounds that neither is consistent with rather less

subtle but far more explicit and even basic components of Frege’s general

philosophical position. Indeed I shall argue that, largely owing to these com-

ponents, the sharpness problem (as I shall call it) is not only inevitable but

ruinous; and hence that Frege’s overall enterprise is not ultimately viable,

Of course in downplaying these components the interpretations of Burge

and Weiner do promise relief from that difficulty. But that signifies little, for

these are avowedly attempts at fidelity, not at reconstruction {in any case I

believe that as reconstructions they would lack the intrinsic strength to

justify the proposed alterations). I shall begin by indicating the Fregean

philosophical commitments which I wish to stress: these concern the status

which Frege assigns to logic, and the peculiar interpenetration he perceives

amongst the notions of truth, judgement and assertion. I shall then explain

why these components make the sharpness problem unavoidable, before

turning to the discussion of Weiner and Burge.

1, Nothing is more central to Frege’s philosophical outlook than his estimate

of the status of logic, He thought of that estimate as implied by the incoher-

ence of psychologism, and it was essential both to the content and to the epi-

stemological importance of his version of logicism. Repeatedly, from his

earliest comments on the subject to his latest, Frege characterizes logic as

comprising the ‘Laws of Truth’ or ‘Laws of Thought’, which pertain to

‘everything that can be thought’; they ‘prescribe universally the way in

which one ought to think, if one is to think at all’? But the way in which

Frege envisages the laws of logic as exerting their jurisdiction over all

thought is not, as we might expect, by virtue of being about thought (or sen-

tences, statements or propositions); not, in particular, by generalizing about

thoughts according to their form, showing for example that all thoughts of a

For these and similar charactrizatons see BG S23 ix; FA §14; PHW’pp. 128, «47,

175 4X8 pp. 199,159, 164-70, 190} CP pp. 112, 336-8, 951-2 (AS pp. 103, 320-2, 42-3) FA ti

88), $105, BL pp. 12-15 (GA r pp. x¥i-wvil). There Is not room here to argue for this

interpretation, but see J. van Heijenoor, “Logic as Caleulus and Logie as Language’, Sti,

17 0967), pp. 924-30; W. Goldlarh, "Logic inthe Twenties, Journal of Sbole Lae, 44 (0979)

pp. 51-685 T. Burge, Frege on Knowing the Third Realm” Mind, 100 (1992), PP- 053-50.

©The oreo Th opel Cos

170 JARY KEMP

given form are true, hence logically true, Logic, rather, stands in the same

first-order relation to reality as any science.

Frege sometimes obscures this point; at FA §87, for example, he charac-

terizes the ‘laws of number’ (hence, by implication, the laws of logic), as

asserting ‘connections between judgements’. But the immediate point there

was to insist on the non-empirical status of arithmetic — to distinguish laws of

number, which, since they contain no predicates of “external things’, are not

‘applicable’ to them, from laws of nature, which do contain such predicates.

The axioms of Begrifischrift generalize about objects and concepts, not judge-

ments. The universality of logic is owed to its extreme generality and abs-

tractness. Whereas the laws of the special sciences set forth the facts co

cerning objects and properties of some particular domain, the laws of truth

set forth what holds of all objects and properties whatsoever. Logic thus

enunciates those maximally general facts; it consists of those axioms and

theorems derivable from them which constrain what may be true, hence

be asserted, within any science, any domain of thought or

reasoning. These are the ‘laws of the laws of nature’, the ‘most general laws’

(FA §87, GA p. xv). For example, whereas Newton's second law tells us that

the force exerted by a material object is equal to its mass multiplied by its

acceleration, Leibniz’ law tells us that for any property F and any objects «

and », if x= y then if Fx then Fy. By universal instantiation, such laws enable

us to derive further truths within more specific domains of knowledge.

‘These laws constitute the ultimate standards of correct argumentation,

for they set out ‘what holds with the utmost generality for all thinking, what

ever its subject matter’, They are given by ‘the very constitution of reason’.

and can be denied only on pain of ‘complete confusion’.’ There is, then, no

question of justifying them (except where provable from other logical laws);

to hold them in suspense would be to renounce reason.* This is in turn what

made the thesis of logicism, the establishment of which was the over-arching

aim of Frege’s most productive years, so compelling. ‘The general applic-

ability of arithmetic (understood to include analysis) was in Frege’s view

incompatible with its deriving from any faculty of sensibility, whether a priori

or empirical, for the applicability of propositions justified by any such source

of knowledge could not extend beyond that source. Nothing could account

for that general applicability, except that it should be included in the ‘Uni:

versal Laws of Thought which transcend all particulars’ (BG Preface). Thus,

if the acceptance of those laws is in some sense a precondition of though

logicism identifies the ‘epistemological nature’ of arithmetic (Ga p. 4

what ma

Pp. 351 (Ap. 342: PHU. 128 (NS p. gos Fi $14, See also Burge in Mind 1993

See the great polemical introduction to Grandgeris pp. xv Xvi, Russell makes the same

point in The Prinaples of Mathomatis $17

The Ft Te Pie th

FREC

‘SHARPNESS REQUIREMENT 17

‘This conception of logic, whereby ‘Every proposition of Begriffeschrift

expresses a thought’, contrasts sharply with the semantic or model-theoretic

conception which is now standard. According to that conception, the

content of logic is not itself expressed by logical formulae; logic, rather,

generalizes about the statements expressible in a particular symbolic system

on the basis of their form, telling us, for instance, that any instance of a

given schema such as ‘Fx ~9 Fy’ is true, which is produced by substituting a

denoting name and an interpreted predicate for ‘x’ and ‘F’ respectively. No

singular epistemic status need be claimed for logic. An explanation of logical

truth is thus available in terms of semantics, and a justification of a proof:

procedure is available in terms of semantic soundness and completeness

proofs. The application of logic is effected by interpreting the formalism, not

by universal instantiation,

Since Frege’s ‘laws of truth’ do not actually employ the notion of truth,

the peculiar need of the semantic conception for that notion, for the purpose

of generalizing about statements or sentences, simply does not arise (Tar-

skian semantics can proceed without recognizing any semantic concepts as

indefinable, but only by restricting itself to languages with finite vocabu-

laries: it is doubtful that any such strategy could cope with all thought)

Logic itself, then, was no obstacle to Frege’s denial that truth, strictly speak-

ing, is a genuine property, something which might explicitly and irreducibly

constitute the characteristic subject-matter of some science, This denial

receives positive substantiation from Frege’s frequently repeated character-

ization of judgement as the acceptance of a thought as true (there is also a

notoriously vexing regress argument, which I shall not discuss). At various

points in his writings, Frege urges that the predicate ‘ — is true’ properly

attaches only to thought-names; but rather than signifying a genuine pro-

perty of thoughts, it serves only as an explicit indication of assertoric force.”

For, although what we accept, in judging that p, is surely the truth of p, the

content of our judgement is just that p. Likewise, to assert that p is true is just

to assert p. This redundancy conception of the truth-predicate and Frege's

non-semantic conception of logic are thus complementary: to say that logic

comprises ‘the most general laws of truth’ is to say that it comprises the most

general laws, not that it concerns a distinctive property in the way that the

laws of motion do.* Whereas the laws of motion contain (for example) the

motion-predicate ‘x is the velocity of »’, Frege’s laws of logic do not actually

contain a truth-predicate (Frege’s horizontal stroke is not a truth-predicate;

CP pp. 164, 352-5 (AS pp. 150, 943-5): PH pp. 19, 294. 258-2 (NS pp. 211,252, 271-2). 1

discuss Frege's dental that truth + a property in G. Kemp, “Fruth in Frege's Laws of Truth’,

forthcoming in Sythe 105 (1996).

"See PHY p. 252 (NS'p. 272). Especially in some early writings, ¢.g, PHW'p. 3 (NS p. 3),

Frege often obscures this

© The rT Poa Con

172 GARY KEMP

whereas thoughts are the proper subject of the predicate ‘is tne’, the

horizontal yields the value false when attached to a name of a true sentence

or thought

2. Let us now consider the sharpness requirement. In view of the status

Frege assigns to logic, the requirement is no mere shrill and dubiously war-

ranted concern that such fallacies as that of the heap might actually arise in

mathematical reasoning. Nor is it merely the observation that the employ-

ment of a concept-script requires that the extensions of predicates be defined

so as to ensure a truth-value for every atomic sentence. It is, rather,

stantive proposition, a theorem of what is both epistemologically and

ontologically the most funcam is, simply, one of the laws of

truth that (Va)(VF\[Fx v ~Fx) that for any concept and any object, «

the object falls under the concept, or it falls under its contradictory. A non:

sharp concept-sign lacks denotation.’ And since every function-sign and

every relation-sign can occur as part of some concept-sign, it follows gener-

ally that there is no such thing as a function not defined for every argument.

and no case in which neither a given relation nor its contradictory holds of a

given pair of objects. Thus, since ‘Fa’ is true if and only ifn object denoted

by the proper name falls under a concept denoted by the concept-sign, it is

true only if the concept-sign is defined for every argument (and false only if

its negation is true}.

The trouble is obvious. Take virtually any ordinary concept-sign you like.

and apparently it will not be true that you can attach any denoting proper

name whatsoever to it and get a sentence which must be either true or false

The implication is that precious little of what we actually think and say is

true or false. There are two sorts of cases. First, some expressions, such as“:

is a heap’, have indefinitely bounded extensions, and are thus neither true

nor false of certain objects to which they can significant! ribed. Frege

maintains that the logical misbehaviour of such expressions shows that they

denote no concept, but the kinds of paradoxes engendered by ordinary

conventions relating to those expressions can be generated, even if less

obviously, with respect to a very wide range of ordinary predicates which we

should be far from acknowledging to be defective. Take away one molecule

from a stone, a bicycle or a galaxy, and it will naturally seem that what you

have is still what it was, and similarly for most ordinary predicates. Second.

most funetion-signs seem significantly applicable only within some proper

subset of the universe of objects in ge

the case of logically simple concept-signs: one could maintain that a given,

simple predicate applies wherever its contradictory fails to apply ~ that, for

a sub-

be as

eral. At most, this could be denied in

PHW pp. 122, 80 (NS pp. 133, 195): CP pp. 448, 40 (AS pp. 145. 290): BL (Gili 80.

Fhe Fann Te Papi ets

FREGE'S SHARPNESS REQUIREMENT 173,

instance, ‘The number three is hungry’ is fale rather than nonsense, and

hence that it is true that the number three is not hungry. However, what

plausibility this position enjoys quickly evaporates when we turn to function-

signs which are not predicates, and to complex predicates involving them.

There is clearly no such thing, for instance, as the square root of San

Francisco, and hence no truth value for ‘Napoleon < (San Francisco)’ ~

not, at least, in keeping with anything like Frege’s account of how the truth-

value of such a predication is determined.

So the conjunction of Frege’s estimate of logic with his logical theory

appears not to allow room for either the truth or falsity of ordinary state-

ments. Even by the most minimal principle of charity, it surely follows that

Frege did not see this. He writes as if he missed it. He repeatedly contrasts

‘admissibility for science’ with ‘myth’ or ‘fiction’; except for the case of

‘heap’, never is an example given of a term which is part of accepted science

or of accepted common-sense truth, but which is said to lack (Fregean) de-

notation." Yet he says repeatedly that logic can ‘recognize’ only sharp con-

cepts, that it ‘presupposes’ their sharpness.* This is fair enough when logic is,

conceived as the construction and interpretation of formal systems, for then

it is part of the bargain to speak a separate or inclusive meta-language from

which to assign objects to singular terms and extensions to predicates, and

thus to secure, from the outside, the wholesome fodder for which such a

scheme is designed. Nothing about reality or language evidently follows

from, and very little is evidently presupposed by, the possibility of such an

activity. But where logic is advanced as the universal ‘laws of the laws of

nature’, no such external perspective is available, and logical formulae such

as that asserting the law of excluded middle acquire a thoroughgoing factual

portentousness; they assert that reality is really like that. It is thus misleading

to speak of what logic can and cannot ‘recognize’; it has already been

defined as recognizing everything. A striking example of this equivocality is

the last footnote to §65 of Grundgesetze, in which Frege inveighs at length

against conditional definitions, ‘It is self-evident’, he declares, ‘that certain

functions must be indefinable, because of their logical simplicity. But these

too must have values for all arguments.” The trouble lay concealed by

Frege’s not having asked himself ‘What exactly is the force of this must?”

Thave described the trouble in a very wooden sort of way, taking Frege’s

explicit views at something like face value; it is natural then to wonder

whether there are not subtleties in Frege’s views which might get him round

" See PHW pp. 122, 186, 191, 232 (NS pp. 133, 202, 208, 50); CP pp. 226, 241, 929 (KS pp.

208, 227); PMCYIU/1 p, 63, VIII/12 p. Bo, XV/4p. 52, XV/8 p 185 (WB xi p. 96, x007

12 p. 128, xx0/14p. 152, 200/18, P24).

“Ex, PHW pp. 1Bo, 229-30 (NS pp. 105, 24

856-65).

TPW pp. 139-50 (GA

©The Enso The Pape oi

174 GARY KEMP.

it, The two attempts at rescue which I shall discuss both involve identifying

such subtleties and extending them in certain ways; I shall argue that those

extensions stray too far from Frege's most general and philosophically basic

commitments, and further that the purported subtleties are simply not

attributable to Frege.

u

I begin with Weiner’s interpretation, as expressed in her book Frege in

Parspectice (Cornell UP, 1990). Her central thesis is that, unlike contemporary

analytical philosophers of language, Frege is not concerned to present an

account either of existing language or of the thought-content it embodies,

but to present an epistemological ideal — the ideal of building up the exact

sciences within a Begrifischrft — and to argue the epistemic importance of

striving for this ideal, gradually replacing ‘unsystematic science’ with

‘systematic science’. Her account is complex, but I think we can safely single

out for discussion the following components of what is very much an

attempt to come to terms with the sorts of difficulties in Frege just described,

According to Weiner (pp. 133-224), Frege recognized that since only

sharply defined concept-signs and proper names have denotation, the signs

of arithmetic, not having been previously so defined, lacked denotation. He

thus held that prior to their being assigned precise meanings by the defin-

itions of his Grundgesetze, mathematical statements, though they expressed

thoughts, lacked denotation, and thus lacked truth-values. The implications

however, are not so deleterious as one might suppose. For one thing,

the propositions constituting pre-systematic arithmetic may be said to be

‘vindicated’ by the fact that what content they possessed is included in the

content of their replacements in systematic arithmetic." But more import-

antly, according to Weiner (pp. 227ff), Frege is committed to a category

difference between science and philosophy, whereby only the former is

capable of embodying truths, strictly speaking. Science, rigorous or ‘ideal’

science, is that which is expressed in a properly constructed Begrifschrft: this

is to contain all the genuine factual content of science. The role of philo-

sophy, for Frege, is only to elucidate, rhetorically to impress upon us what

such rigorous science is like. It is not to describe language as it is in point of

fact; it is not aimed at ‘objective theorizing or the establishment of truths’

Weiner p. 245). For it cannot itself satisfy the requirements of rigorous

science; therefore such elucidation must fall short altogether of factual

statement. It may be successful or unsuccessful in inculeating the requisite

"Weiner p. 136; see also pp. 97-8, 112, 193, 228

0h ans Pe Pp! i

FREGE'S SHARPNESS REQUIREMENT 75

awareness, but it cannot be true or false. Frege frankly acknowledges the

ultimate ineffability of his distinction between objects and concepts ~ saying,

famously, that any attempt in natural language to convey the distinction

‘must miss my thought’; Weiner's claim is that he thought of the rest of his

informal writings in much the same way. His logical and semantic theory,

then, and in particular the sharpness requirement, have no factual implic-

ations for ordinary thought and discourse. When we say that ordinary words

lack Bedeutung we are not, strictly speaking, asserting anything about the

objective status of ordinary discourse; at most, we are saying that those

words lack the precise definitions of the signs of systematic science

This is not the place to raise merely general doubts about the intelligi

bility of the notion of elucidation, of a distinction between factual and non-

factual discourse according 10 which, it seems, no such distinction can

actually be stated. For that, we can turn to the voluminous literature on

Wittgenstein’s Tractatus. Instead, | shall first make a textual point — that

Frege’s remarks on elucidation are far narrower in scope than Weiner

claims — before arguing that the features of Frege’s position I have been

stressing simply leave no latitude for a systematic/unsystematic distinction to

play the role Weiner envisages for it

Frege certainly did think of some of what he wrote as elucidation. On a

number of occasions he was positively emphatic that, although it is some-

times important to ensure, by means of examples or elucidation, that all

investigators grasp the primitive terms of a science in the same way, that

activity is not to be confused with formal definition, and indeed is not part of

the content of the science at all. A passage from a letter to Hilbert is typical:

I would not want to count [elucidations} as part of mathematics itself, but refer them

to the antechamber, the propaedeutics. Th

re similar to definitions in that they too

are concerned with laying down the meaning of a sign (or word), If such a case the

meaning to be assigned is logically simple, then one cannot give a proper definition

but must confine oneself to warding off unwanted meanings among those that occur

in linguistic usage and to pointing to the wanted one, and here one must of course

always rely on being met half-way by an intelligent guess. Unlike definitions, such

clucidatory propositions cannot be used in proof because they lack the necessary

precision, which is why I should like to refer them to the ante-chamber.

But Weiner infers too much from this. In this and other passages in which

Frege explicitly discusses the role of elucidation there is nothing to indicate

that he is making anything but a relatively narrow point about the dis

tinction between what is primitive and what is defined in a theory; the

philosophical lesson is just that only a genuine formal definition, usable in

"PMC IV/s pp. 36-7 (WB xv/5 p. 63 see also CP pp. 182, 300-1 (KS pp. 167-8, 288);

PHW pp. 207, 231 (NS pp. 224, 290)

Th Pel Coe

176

proofs, can actually be credited with showing that proven results depend on

an analysis of the term defined. Elucidation is aimed at ensuring the mutual

grasp amongst scientists of the undefined terms. The only clear implication

of Frege’s remarks on elucidation, for an essay like ‘Uber Sinn und Bedeutung’,

is that it must leave some concepts undefined — perhaps such concepts as

Sinn and Bedeutung ~ not that it advances no theory. Indeed, it does not even

follow from the need for elucidation that elucidatory propositions cannot be

true or false; as a definition, it would be circular, for instance, to say °A

conjunction is true where the first conjunct is true and the second conjunct

is true’, but not thereby untrue.

More cogent, then, would be to argue that since Frege did recognize that

nothing he could say in his famous response to Kerry could actually state

the distinction he wished to insist upon between concepts and objects, he

was aware that some points in logical theory could not actually be stated:

he may, then, have been prepared to extend the same verdict to his other

philosophical writings. But this would again be to infer too much. The con-

cept horse problem, as it has come to be known, is a very special case. The

idea is to insist upon a strict and exclusive distinction of syntactic roles to be

fulfilled by proper names and predicates, so that neither could sensibly

occupy places occupied by the other. The distinction is ‘grounded deep in

the nature of things’ rather than in linguist

material mode of speech could state the requirement without violating it,

and hence lapsing into nonsense."

Frege perceives this very vividly, and is at pains to point out the oddity of

the situation; his considered position is close to Wittgenstein’s doctrine

of formal concepts, whereby something’s being, for instance, an object can

only be shown by its syntactic category, not indicated by a predicate. But

however problematic it may ultimately be, no immediate paradox of unsay-

ability arises in the case of the doctrine of sense and denotation, and Frege

never suggests that there is any such difficulty. In contrast with his frequent

the writings on sense and

other logical matters just do present themselves as describing how it is in

point of fact with thought and language. Indeed, contrary to the impression

which Weiner conveys, Frege's writings on these subjects tend to focus

almost exclusively on ordinary language (rather than on a concept-script),

which would be an extremely ill-conceived strategy if his real aim were not

to describe the way language works in general, but only to com

appreciation of what a concept-script is. Some telling examples: he points

out that such a sentence as ‘Scylla has six heads’ expresses a thought but

lacks truth-value because of the denotation failure on the part of ‘Scylla’

convention, but nothing in the

warnings over the words ‘concept’ and ‘objec

an

2» PMC XN /; pp. 1gt-2 (VB xxxi/7 p. 234)

FRE

HARPNESS REQUIREMENT 7

(PHW p. 225/NS p. 243); while discussing ordinary examples he says that to

the sense of a predicate there also corresponds something in the realm of

denotation (PHW p. 255/NS p. 275); he equates a thought’s being neither

true nor false with the lack of truth-value on the part of any sentence which

expresses it (PHW p. 232/NS p. 250); in §§56-67 of Grundgesetze he introduces

the doctrine of definition in connection with ordinary language, and only

then declares that it ‘holds good of arithmetical signs’; he declares late in life

that he ‘never had any doubt that the numerals designate something’ (PHW

p. 275/NS p. 295); he says that the truth-values ‘are recognized, if only

implicitly, by anyone who undertakes to judge’ (CP p. 163/K3 p. 149); he

says ‘If words are used in the ordinary way, what one intends to speak of is,

what they denote’ (CP p. 159/A8 p. 145).!” Weiner’s position on Frege’s use

of his apparent semantic vocabulary would require that virtually all of

Frege’s informal work must be regarded as wantonly misleading.

But the claim that Frege thought of so much of his informal work as

elucidation is, so to speak, only textually problematic. What disturbs rather

the substance of Frege’s thought is that Weiner thinks of this as a con-

sequence of Frege's idea that only systematic science — that conducted by

means of a concept-script ~ generally satisfies the constraints set down by

means of such elucidation. Thus Weiner observes that, given Frege's

constraints upon the denotations of concept- and function-signs, it seems

inescapable that pre-Fregean arithmetical signs lacked denotation, and con-

sequently that pre-Fregean arithmetical sentences lacked truth-values; but,

since there is nothing peculiarly defective about the signs of arithmetic,

Frege’s constraints upon denotation imply that sentences of ordinary

language and existing science, all or virtually all of them, lack truth-values.

In placing the systematic/unsystematic distinction at the centre of Frege’s

thought, Weiner thus goes beyond accepting that Frege’s logical theory has

this consequence; her claim is that Frege actually perceived and accepted it,

even if he was too cunning to say so. Weiner does not say right out that

Frege accepted that few if any pre-systematic sentences have truth-values,

but it follows too immediately from what she does take to have been Frege’s

consciously held view ~ that only in a properly constructed Begriffschrift can

denotation and hence truth-telling take place ~ for there to be room for

attributing the ground but not the consequence.

It might be thought that there is nothing so remarkable in this; Frege

would not, after all, have been the first to hold that only in the most rigorous

of scientific discourse can strict truth be achieved. Descartes, for instance,

held that perception has only ‘some truth in it’. Indeed, Weiner says that it

does not follow from the position she attributes to Frege that pre-Fregean

On Bedeutung see PMCXV/14 p. 152 (WB xxxvil14 p. 235).

{© The Ess of The Pipi rt

8 GARY KEMP

arithmetic was simply ‘wrong’; for if what theoretical content it possessed

could be preserved, but suitably augmented and sharpened, by a systematic

science, then it admits of being vindicated, The same could presumably be

said of any domain of discourse; an arbitrary statement could be defined as

something like ‘correctly assertable’ just in case it is true on all interpreta~

tions which preserve what is determinate and unproblematic in its existing

interpretation (it would be circular to define a statement as true if and only if

truc on all such interpretations). Frege gives no indication of actually having

held such a view, but since he plainly did think ordinary discourse unsuit-

able for scientific purposes as it stands, it might be thought that, in the spirit

of charitable reconstruction, he ought to be interpreted as having held it

But he cannot be ~ not without the sacrifice of some of his most important

and frequently stated views. In particular, it would disturb the interpenetra-

tion, described in §I above, which Frege thought he had discovered amongst

the notions of truth, judgement and assertion, To judge, for Frege, is ‘to ac-

cept a proposition as true’; the other side of the same coin is that to ascribe

the words ‘is true’ to a proposition is just to assert it, Thus, if only statements

of a Begrffischrift achieve truth-values, then, wherever one is unavailable, we

should, preposterously, have to refrain from judging and asserting alto-

gether, Further, the redundaney-conception of the truth-predicate

cludes our trying to smooth things over by saying things of the form ‘Well.

do say that f; I do not say it is strictly speaking a TRUTH that p’. The

proposed reconstruction does nothing to address these points, and could be

advanced only on pain of abandoning Frege’s account of the wuth

judgement-assertion trinity. Frege simply has no place for a region of

assertion which aims at anything less than truth

Some of what Weiner says might suggest that she could take another line

She argues at Iength (pp. 1g0ff) that, since Frege’s philosophical work is

aimed only at characterizing ideal science, Frege's Bedeutung — what I have

been rendering as ‘denotation’ — should not be equated with the ordinary

notion of reference, understood as a word's ‘hooking on to" an extra-

linguistic entity. Thus, in order to avoid the extreme consequences just de-

scribed, one might suppose that Fregean denotation is simply not to be

invoked in discussing ordinary sentences (ignoring the fact that he does in-

voke it); one might then suppose that ordinary sentences do in general have

truth-values in virtue of what their components on some level refer to, in

this ordinary sense, even if their parts do not achieve denotation, in Frege's

special, technical sense. But this is not coherent. Fi laws of truth are to

‘extend to everything that can be thought’; they ‘hold with the utmost

generality for all thinking’ (he also declares that he ‘cannot recognize

1th ais ot hepa

FREGE’S SHARPNESS REQUIREMENT. 179

different meanings of the word “true”""), If the notion of denotation is to be

involved in an exposition of the laws of truth, and ordinary sentences

express truths, then the notion of denotation is appropriately invoked in

connection with them. Or, to put it the other way round, if ordinary sent-

ences express truths, stand in logical relationships, and so on, then whatever

concepts are needed in explicating those phenomena — reference, for

instance ~ are those which ought to he employed in expounding the laws of

truth. It would be in terms of these that one should attempt to describe the

character of a Begriffischrift, the ideal forum for truth-telling.

One might resist these criticisms on the grounds that they illegitimately

derive consequences from an elucidatory quasi-theory, as if it were intended

as factual. But if elucidation is worth engaging in at all ~ and if Frege's

informal writings are worth debating about ~ then there is no choice but to

deal with it as if it were so intended. We must at any rate complain if itis

nly true,

not coherent, or inconsistent with what is more cert

ul

Burge claims to have discovered the materials in Frege necessary to address

the sharpness problem more directly." Frege does not, according to him,

accept the inference from our not understanding anything by a predicate

which delimits a sharp concept to the conclusion that it fails to denote a ger

uine Fregean concept. According to Burge, Frege holds that expressions of

pre-systematic scientific discourse and even ordinary discourse do in general

express logically adequate senses, and do in general achieve denotation; itis

just that we are not in general fully cognizant of the senses with which we

operate, and which our words express, in the self-conscious way which

would be achieved by systematic or ideal science. We perceive the sorts of

difficulties T have been discussing only because we assume that if the users

of an expression, taken either individually or collectively, neither apprehend

clearly and distinctly a definite sense nor determine one by their use of the

expression, then the expression has no definite sense. This manifests a

contemporary naturalistic tendency to regard sense or meaning as neces-

sarily being shown forth by linguistic practice or intuition, a tendency which

on Burge’s reckoning is quite foreign to Frege. Fregean sense is not to be

equated with linguistic meaning. It may be that no amount of considered

articulation of linguistic meaning will elicit the senses we engage with in

using our words as we do,

"PMC I11/g p. 20 (WB iv/ p. 94). It might be objected that this remark is being pulled

out of context

7. Burge, ‘Frege on Sense and Linguistic Meaning’, in D. Bell and N. Cooper (eds), The

Analytic Tradition (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1990), pp. 30-60.

(©The es Tr Pl tn

180 GARY KEMP

Of course this will seem a dark and gratuitous doctrine unless some

positive account is sketched of what does make it the case that we are

thinking with this sense rather than that. But Burge finds such a account in

Frege: Frege believes, he claims (p. 49; see also pp. 48, 51), that the senses

with which we operate are those which would be brought to light by a full

analysis of an ideal and complete true theory of the world:

Frege’s view [is] that the ultimate foundation and justification of current linguist

practice may supplement ordinary understanding in such a way as to attach it to a

definite sense that no one may currently be able to articulate adequately, or

thoroughly grasp. The presupposition is that some of our practices are founded on a

deeper rationale or on deeper aspects of “reality” than a have presently

understood... Frege must sce full understanding as guaranteed only by a completely

Fundamental and completely satisfactory theory

Reflexive conceptual clarity may have to await thoroughgoing knowledge

of what is the case, but this could not be so if judgements were not already

taking place which embodied those concepts. It seems to follow that there

must be a mode of cognitive engagement, with the right set of concepts,

which is prior to the achievement of that sort of clarity

One of Burge’s aims is the need to solve the ‘interpretative puzzle’

presented by the seemingly disastrous consequences of Frege’s strictures on

denotation. His case is based almost entirely upon certain passages from the

monograph ‘Logic in Mathematics’, in which Frege describes unimpeach-

ably competent users of words which express certain senses as grasping those

senses only tenuously, or as if perceiving them through a haze. Frege speaks

in this way so as to make it intelligible that there should be such gross errors

as those made by many of his contemporaries ~ none other than Weierstrass

is the stalking-horse ~ in their analyses of basic mathematical concepts. Such

thinkers are seduced into believing their definitions to be adequate, when

in fact nothing of mathematical consequence follows from them: their belief

that their definitions are adequate, Frege supposes, is sustained, not by find-

ing the latter to engender the right consequences, but by being covertly

guided by a correct but implicit ‘inkling’ of the notions they purport to

lyse. Such thinkers engage with the sense in a way sufficient for the

practice of arithmetic, but without completely understanding it. Thus the in-

definiteness of linguistic intuition does not entail that no determinate sense is

actually grasped.

I shall not question the intrinsic plausibility of such a view, focusing in-

stead upon the following objections: (1) that it represents only a very partial

solution to the sharpness problem; (2) that it renders the notion of sense

incapable of fulfilling its most explicitly advertised purpose; (3) that the texts

cited by Burge do not actually support its being attributed to Frege.

The Eu The Pap en

FREGE'S SHARPNESS REQUIREMENT 181

1. That our logical and mathematical powers spring from our contact

with abstract entities which we may be unable to articulate is a claim of

long-standing cogency. But outside logic and mathematics its plausibility

lapses precipitously: where less abstract notions are concerned ~ the concept

of a house, a mountain or a river — sense is surely just the conventional

meaning determined by practice, actual and potential. But this fact is

crucial: the problem generated by the ‘requirement’ that concepts must be

sharp was that it is actually a substantive theorem of that science which is

presupposed by all science, all knowledge. Burge’s proposal does nothing to

show how, consistently with Frege’s position, everyday statements might

acquire truth-values.

2, In the main discussions in ‘On Sense and Meaning’ and ‘On Function,

and Concept’, the peculiar office of the notion of sense was to take up the

apparent cognitive slack amongst co-denotational terms, thereby identifying

those differences as objective.” But if a thought need not be transparent to

the thinker who is, nevertheless, in a position to affirm or deny it, then

subjective impressions of cognitive difference need not so readily be thought

to betoken differences of objective content, This not only prevents the

notion of sense from playing the epistemological role for which it was most

cogently recruited. It threatens to undermine what ought t0 be a quite

innocuous version of a Fregean standard for individuating senses ~ that the

senses of ‘6’ and ‘c’ differ where ‘A believes that ... b.” and ‘A believes that

¢...” are logically independent (this is weaker than the principle whereby

thoughts differ when it is possible rationally to affirm one but deny the

other). Ifa thought need not be distinctly apprehended in order to affirm or

deny it, then there is no reason to exclude the possibility that one might

believe the thought expressed by *.. 6...” but deny that expressed by *..¢..,

when in fact they are the same thought. That Frege regarded that standard

of individuation as something more than contingently true is indicated by a

claim he often repeats about judgement: when we judge, according to Frege,

we are ‘poised between opposites’; to judge is to commit oneself, to choose

amongst mutually exclusive alternatives, so that “The acceptance of [the

thought} and the rejection of [its negation] are one and the same’."” By

definition, then, just as a woman torn between two suitors cannot he said to

have chosen until she rejects one of them, we cannot judge that p but also

that not-p. Such a claim seems absolutely right if the object of judgement is

io

"See, for instance, the discussion in ‘Function and Concept’ (CP pp. 144-5/48 p. 132),

Frege also argues thus in “On Sense and Meaning’ (CP pp. 157-8/43 pp. 143-4}, GA §2:

PHW p. 192 (NS pp. 208-), and in letters to Peano (PMC XIV/1t pp. 127-8/ WB xxxiv/11

pp. 196-7) and Jourdain (PMC VIIL/12 p. 8o/ WB p. 128),

PHW pp. 7-8, 149, 185, 198 (NS pp. 7-8, 161, 201, 216-17); CP pp. 380-5 (KS pp. 369-74)

1 Theos The Ppl Qi,

182 GARY

P

conceived as what is explicitly understood by the judging subject, but if not,

then it is surely contentious

3. OF course Burge is well aware of these points, and is himself a leading

promulgator of the central realization of recent philosophical semantics, that

a person’s state of understanding, on any untendentious conception of

‘understanding’, cannot in general be sufficient for determining the truth-

conditions of what that person says. Perhaps it has come to seem incredible

that it should be, but that is not the issue. The issue is whether there is

anything in Frege’s work to suggest that he accepted that those things might

come apart (even where indexicality is not involved). And I think it clear

that Burge has misappropriated the passages which form the textual ca

the claim that he did. The passages, it will be recalled, concerned the plight

of otherwise exemplary mathematicians such as Weierstrass, who advance

grossly unsatisfactory definitions of mathematical terms which they none the

less use correctly; Burge infers that this betrays a want of understanding of

those terms on their part, thus showing that, in Frege’s view, fuzziness of

understanding does not entail non-sharpness of sense. Frege does speak of

such mathematicians as being ‘unclear’ on concepts, and he says such things

as that Weierstrass’ sentences ‘express true thoughts, if they are rightly

understood’. But, as we shall see in a moment, there is a crucial sort of

ambiguity in such words as ‘understanding’ and ‘clarity’, which shows

Burge’s inference to be unwarranted, The underlying purpose which is

exercising Frege in this discussion is to grind the old axe about the nature of

definition. People typically assume that the correctness of a definition can be

recognized by how it seems to us when we grasp it. Nothing could be further

from the wuth. The substance of Frege’s divorce of cognition from phen-

omenology, and of its corollary, the context principle, can be summed up by

saying that neither thought, nor thinking abou! thought, is like perception, as

if a thought were like a mental image, or a kind of picture or diagram, held

before the mind’s eye." What shows a definition to be correct, rather. is that

you can prove the right theorems with it, and nothing else. Weierstrass,

presumably unmindful of the exemplar provided by his arithmetical de-

finition of limit, had given a logically useless explication of the natural

numbers and arithmetic operations, because he had appealed to psychologi-

cal processes and intuitive images rather than logically relevant conceptual

content; his attention had wandered into the inner psychological ‘peep-

show’, as Frege had put it in Grundgesetze (PHW’ p. 217/NS p. 234). Nothing

trotted out from there could ever serve as a logical analysis of a concept of

"See PHW’ pp. 137. 144-6 (NS pp. 149

38-60. Sec also G. Kemp, ‘Salmon on Fre

Philosophical Studies, 78 (1995). PP. 153-62

156-8): CP pp. 371-2 (KS pp. 361 2) FA S26,

igean Approaches to the Paradox of Analysis

FREGE'S

HARPNESS REQUIREMENT 183

arithmetic, however useful as elucidation it might be. But, by the same

token, the inadequacy of such an explication does nothing to cast serious

doubt on Weierstrass’ grasp of the relevant concept. It is not so much an

unsuccessful attempt at definition as a confused endeavour with no clearly

conceived purpose. That someone should make that sort of mistake has

nothing essentially to do with his grasp of a concept; he is in a muddle about

definition, not about arithmetic (and it is not just that he cannot define ‘de-

finition’; what he calls ‘definitions’ are no such things). That is what Frege

means by saying that Weierstrass ‘lacks the ideal of mathematics’. There is

nothing to suggest that if Weierstrass knew what definition was — possessed

the ideal — he would be any less well placed than Frege himself to give ad-

equate definitions. His, so to speak, first-order understanding of arithmetical

signs is manifested by what propositions involving the concept he accepts as

true and what propositions involving it he is prepared to infer from others."

Since Weierstrass actually operates in these ways with arithmetic concepts as

well as anyone, this is simply not a case of someone who operates with a

sharp sense but whose employment of that sense is vague. He stumbles, as it

were, not when thinking with the sense, but when asked to think about the

sense, to give a definition. Burge’s idea, by contrast, was to give content to

something still more extreme; the proposal was that the sense employed by a

person might be sharp when his employment of it was not, thus sorting out the

difficulty we have been discussing in Frege’s position. The inability of

Weierstrass to define a given concept which he does employ sharply ~ or as,

sharply as anyone ever employs a concept ~ does nothing to show how

words which are not used precisely can nevertheless express sharp senses.

“That was the gap in Frege’s picture that wanted filling

‘Thus that exemplary users of an expression should take a wrong defin-

ition for a right one, or vice versa, does not show that understanding or

linguistic intuition is inadequate as a guide (o sense. The only linguistic

intuitions relevant to the sense/linguistic-meaning relation would be those

providing evidence for what would be said, in the material mode of speech,

in hypothetical situations. Burge has said nothing to show that Frege

thought that that sort of evidence could not adequately reveal the senses

actually expressed by words. Thus I cannot see that he has shown that

Frege’s position is not undermined by the sharpness problem, It is true, as

Burge says in support of his claim that Frege thinks that most words do

express denotation-determining senses, that ‘Frege repeatedly writes as if fic-

tion and serious mistakes are the primary sources of failures of denotation’.

I suggest that the explanation of this which best respects the letter of Frege's

" Sce PHW’p, 222 (Np. 240)

Mh tl Fe Papel ra nag

184 GARY KEMP

writings is that Frege never quite saw, or would not acknowledge, that the

severe demands imposed by his logic and theory of meaning cannot, accord-

ing to his philosophical conception of logic, be withheld from any region of

thought or discourse. Or he too readily assumed that normally those con-

ditions are met. To say this is quite different from saying that Frege actually

harboured the ‘secret doctrine’ that ‘nearly all sentences in actual use,

strictly speaking, express neither truths nor falsehoods’, as Burge imagines,

(p. 37) an opponent of his interpretation, such as Weiner, might suppose.

Vv

‘There is justice in both Weiner’s and Burge’s admonitions not to assimilate

Frege’s concerns too readily to those of con

of language. But it would be surprising if the best way to protect the

integrity of Frege’s work from that sort of arrogation were to discover in it a

previously overlooked subtlety which transforms its entire aspect. Such a dis-

covery would in any case assort very oddly with Frege’s great and exemplary

lucidity, indeed his avowed earnestness not to gain the kind of immunity 10

incisive criticism afforded by sententiousness or equivocality.2” What neither

Burge nor Weiner considers with due care is the less stirring, but not merely

jejune, hypothesis that Frege simply failed to see, or failed to acknowledge,

the collision between his universalist logic and its accompanying account of

meaning and objective cognition. Whether this was self-deception, or failure

of perception, we are truer to what Frege prized most in intellectual matters

to find, in his position, an unacceptable consequence implied by a set of

clearly enunciated and individually compelling doctrines, than we are if we

conclude that he sought to avoid it by surreptitiously holding a more re-~

condite doctrine which can only very problematically be claimed w be

expressed in what he wrote

-mporary analytical philosophy

Chiversity of Waikato

‘See the Introduction to Grundgeset2, especially pp. xix-xxiv; also the reviews of Schubert

Cohen, Schroder and Biermann, and the later attack on Thomae (Renewed Proof of the

possibility of Mr Thomae’s Formal Arithmetic) all in CP (AS,

The rs Ty spt!

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- SurangamaDocument352 pagesSurangamastudboiNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Arnswald Wittgenstein EUKLID1Document168 pagesArnswald Wittgenstein EUKLID1feripatetik100% (5)

- Irish Sentence StructureDocument24 pagesIrish Sentence Structures_j_darcy100% (3)

- Turabian Citation Style GuideDocument2 pagesTurabian Citation Style Guides_j_darcy100% (1)

- Alperovitz Et Al - The Next System ProjectDocument22 pagesAlperovitz Et Al - The Next System Projects_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Grid Portrait Letter For PrintingDocument1 pageGrid Portrait Letter For Printings_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Korean Romanization ChartDocument1 pageKorean Romanization Charts_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Frege On VaguenessDocument23 pagesFrege On Vaguenesss_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Lined PaperDocument1 pageLined Papers_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Ronald Dworkin, Justice and The Good Life-1990Document23 pagesRonald Dworkin, Justice and The Good Life-1990s_j_darcy100% (1)

- Abbey ThesisDocument85 pagesAbbey ThesisBill BuppertNo ratings yet

- Diary Gottlob FDocument40 pagesDiary Gottlob Fs_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Environmentalism As If Winning MatteredDocument12 pagesEnvironmentalism As If Winning Mattereds_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- CARNAP Stone, Abraham 2006 Carnap and Heidegger On Overcoming MetaphysicsDocument28 pagesCARNAP Stone, Abraham 2006 Carnap and Heidegger On Overcoming MetaphysicsMarlene BlockNo ratings yet

- Kitcher - Religion Science and DemocracyDocument14 pagesKitcher - Religion Science and Democracys_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Memo On Parental Leave ArrangementsDocument31 pagesMemo On Parental Leave Arrangementss_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Tres Fases de FoucaultDocument3 pagesTres Fases de FoucaultAndres OlayaNo ratings yet

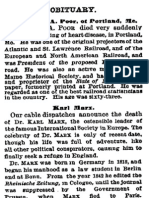

- Marx ObituaryDocument1 pageMarx Obituarys_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Diversity of Tactics - HandoutDocument1 pageDiversity of Tactics - Handouts_j_darcyNo ratings yet

- Environmentalism As If Winning Mattered by Steve DarcyDocument17 pagesEnvironmentalism As If Winning Mattered by Steve Darcys_j_darcyNo ratings yet