Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Nicky Rousseau, University of The Western Cape Eastern Cape Bloodlines

Nicky Rousseau, University of The Western Cape Eastern Cape Bloodlines

Uploaded by

Thandolwetu Sipuye0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views1 pageThis paper examines the exhumation of human remains from a farm near Cradock in the Eastern Cape in 2007. It discusses how "bloodlines" can be assembled or not assembled to establish individual identification and personhood. Nationhood in this context rests on other "bloodlines" running through the histories of property and perpetration at this location, including the murders of Steve Biko and others. The paper considers the tensions between exhumation as recovery and recuperation, and as a process that disassembles existing connections between place, time, objects, bodies, and more. It draws attention to the work needed to stabilize exhumed bodies that claims of history, justice, and nationhood rely upon.

Original Description:

A

Original Title

Rousseau Abstract

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis paper examines the exhumation of human remains from a farm near Cradock in the Eastern Cape in 2007. It discusses how "bloodlines" can be assembled or not assembled to establish individual identification and personhood. Nationhood in this context rests on other "bloodlines" running through the histories of property and perpetration at this location, including the murders of Steve Biko and others. The paper considers the tensions between exhumation as recovery and recuperation, and as a process that disassembles existing connections between place, time, objects, bodies, and more. It draws attention to the work needed to stabilize exhumed bodies that claims of history, justice, and nationhood rely upon.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

22 views1 pageNicky Rousseau, University of The Western Cape Eastern Cape Bloodlines

Nicky Rousseau, University of The Western Cape Eastern Cape Bloodlines

Uploaded by

Thandolwetu SipuyeThis paper examines the exhumation of human remains from a farm near Cradock in the Eastern Cape in 2007. It discusses how "bloodlines" can be assembled or not assembled to establish individual identification and personhood. Nationhood in this context rests on other "bloodlines" running through the histories of property and perpetration at this location, including the murders of Steve Biko and others. The paper considers the tensions between exhumation as recovery and recuperation, and as a process that disassembles existing connections between place, time, objects, bodies, and more. It draws attention to the work needed to stabilize exhumed bodies that claims of history, justice, and nationhood rely upon.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

Nicky Rousseau, University of the Western Cape

Eastern Cape bloodlines

If red is politics, tradition, and also that which is read, then red is also violence and

bloodlines. This paper thinks about the different ways in which bloodlines can be

assembled - or not - by examining the exhumation of human remains from a farm near

Cradock in the Eastern Cape in 2007.

While bloodline is regarded as the most reliable forensic requirement for individual

identification, establishing or, following Zoe Crossland, producing - personhood requires a

different kind of assembling, one that centres around hands and their handling of artefacts

and bone. Both identification and personhood rest on techniques and assemblages of, among

others, forensic medicine, physical anthropology, criminology and increasingly the

testimonial practices of transitional justice. Nationhood, on the other hand, in which these

particular bodies were (and continue to be) entangled, rests on yet other bloodlines that run

through histories of property (prison and police station, holiday farm, hunting lodge and

abbatoir) and perpetration (the murders of Steve Biko, Siphiwo Mtimkhulu,Topsy Madaka,

the Pebco 3, the Cradock 4, the Motherwell 4).

In thinking about these particular bloodlines and the ways in which they are assembled

(including here), this paper works with the tensions between exhumation as a project of

recovery and recuperation, one that is not dissimilar to that of recording and writing hidden

histories or recuperating silenced voices, and one that disassembles existing assemblages

of place and time, material and symbol, human and animal, and the body itself. Focusing on

disassembly draws attention to the work that is expended in stabilising the exhumed body,

upon which the claims of social history, transitional justice and nationhood rest.

You might also like

- Body of Power, Spirit of Resistance: The Culture and History of a South African PeopleFrom EverandBody of Power, Spirit of Resistance: The Culture and History of a South African PeopleRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Clea Koff Forensic AnthropologistDocument3 pagesClea Koff Forensic AnthropologistSydney MacekNo ratings yet

- Spooky Archaeology: Myth and the Science of the PastFrom EverandSpooky Archaeology: Myth and the Science of the PastRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Binford 1971Document24 pagesBinford 1971Rodolpho Silvia de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Ant Group PaperDocument4 pagesAnt Group Paperapi-252856164No ratings yet

- Deviant Burials in ArchaeologyDocument26 pagesDeviant Burials in ArchaeologyPodivuhodny Mandarin100% (1)

- The Beast Within' Race, Humanity, and Animality PDFDocument20 pagesThe Beast Within' Race, Humanity, and Animality PDFanjanaNo ratings yet

- The Archaeology of Death From Social Personae' To Relational Personhood' Mihael BudjaDocument12 pagesThe Archaeology of Death From Social Personae' To Relational Personhood' Mihael BudjaDavor PečarNo ratings yet

- Viveiros de Castro - Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism (Copie en Conflit de Clément CARNIELLI 2017-09-27) PDFDocument21 pagesViveiros de Castro - Cosmological Deixis and Amerindian Perspectivism (Copie en Conflit de Clément CARNIELLI 2017-09-27) PDFpolakantusNo ratings yet

- Eric R. Wolf, Perilous IdeasDocument13 pagesEric R. Wolf, Perilous IdeasFrancesco AndriolloNo ratings yet

- The Body Sacrificed A BioarchaeologicalDocument34 pagesThe Body Sacrificed A BioarchaeologicalfugicotorraNo ratings yet

- Knörr - 2010 - Contemporary Creoleness - Or, The World in PidginizationDocument30 pagesKnörr - 2010 - Contemporary Creoleness - Or, The World in PidginizationBeano de BorbujasNo ratings yet

- Chronically Unstable Bodies (Vilaca)Document18 pagesChronically Unstable Bodies (Vilaca)Carlos Juárez VelascoNo ratings yet

- Clio/Anthropos: Exploring the Boundaries between History and AnthropologyFrom EverandClio/Anthropos: Exploring the Boundaries between History and AnthropologyNo ratings yet

- Näser Equipping and Stripping The DeadDocument22 pagesNäser Equipping and Stripping The DeadJordynNo ratings yet

- Anthropology and DemographyDocument13 pagesAnthropology and DemographyTristan MagistradoNo ratings yet

- Scheper-Hughes - Militant AnthropologyDocument33 pagesScheper-Hughes - Militant AnthropologyNaaomy DuqueNo ratings yet

- ILJ 6.1 ErmineDocument11 pagesILJ 6.1 Ermineeli_s173No ratings yet

- Europe, Race and Diaspora - Susan Arndt - Academia - EduDocument18 pagesEurope, Race and Diaspora - Susan Arndt - Academia - EduSusan ArndtNo ratings yet

- David Wengrow and David Graeber, Farewell To The "Childhood of Man": Ritual, Seasonality, and The Origins of Inequality', Journal of The Royal Anthropological Institute, 2015 .Document23 pagesDavid Wengrow and David Graeber, Farewell To The "Childhood of Man": Ritual, Seasonality, and The Origins of Inequality', Journal of The Royal Anthropological Institute, 2015 .OSGuinea100% (1)

- More Than Just Bones: Ethics and Research On Human RemainsDocument168 pagesMore Than Just Bones: Ethics and Research On Human Remainsprofessor0858100% (1)

- Cannibalism Ecocriticism and Portraying The JourneyDocument10 pagesCannibalism Ecocriticism and Portraying The JourneyMousumi GhoshNo ratings yet

- Queer Ecology Critique - Georgetown 2014Document104 pagesQueer Ecology Critique - Georgetown 2014Evan JackNo ratings yet

- Department of Celtic Languages & Literatures, Harvard UniversityDocument56 pagesDepartment of Celtic Languages & Literatures, Harvard UniversityMr Yuma BurgessNo ratings yet

- Death Warmed UpDocument29 pagesDeath Warmed UpVerónica SilvaNo ratings yet

- N'tacimowin: Our Coming in Stories. Wilson CWS, 2009Document8 pagesN'tacimowin: Our Coming in Stories. Wilson CWS, 2009Alex WilsonNo ratings yet

- Boustan&Sanzo HTR Final - Revised-1 TCCDocument31 pagesBoustan&Sanzo HTR Final - Revised-1 TCCBrenda SousaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare and The Senses: Holly DuganDocument15 pagesShakespeare and The Senses: Holly DuganSukanNo ratings yet

- Rogers Short Essay 2Document6 pagesRogers Short Essay 2api-621525562No ratings yet

- Locating A Tranimal Past: A Review Essay of Tranimalities and Tranimacies in ScholarshipDocument6 pagesLocating A Tranimal Past: A Review Essay of Tranimalities and Tranimacies in ScholarshipyotamNo ratings yet

- Crossland 2015Document19 pagesCrossland 2015Pola Alejandra DiazNo ratings yet

- Ova Donation and Symbols of Sub - Konrad, MonicaDocument26 pagesOva Donation and Symbols of Sub - Konrad, MonicaataripNo ratings yet

- Forensic Archaelogoy Humanistic ScienceDocument2 pagesForensic Archaelogoy Humanistic ScienceRodrigo MictlanNo ratings yet

- Understanding Cultural LandscapesDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Cultural Landscapesstephen_duplantier100% (1)

- Chapter 8Document26 pagesChapter 8Jorge CayoNo ratings yet

- Pampa La Cruz A New Mass Sacrificial Burial Ground During The Chim Occupation in Huanchaco North Coast of PeruDocument87 pagesPampa La Cruz A New Mass Sacrificial Burial Ground During The Chim Occupation in Huanchaco North Coast of Peruabeeja.reinaNo ratings yet

- Queer Anthropology Cambridge Encyclopedia of AnthropologyDocument20 pagesQueer Anthropology Cambridge Encyclopedia of AnthropologyAndrea TaiboNo ratings yet

- Two Spirit Muxe Zapotec IdentityDocument14 pagesTwo Spirit Muxe Zapotec IdentityCalibán Catrileo100% (1)

- 21A.100 End-Of-Term Study Questions December 2004Document3 pages21A.100 End-Of-Term Study Questions December 2004Rino TimonNo ratings yet

- The Mosaic DistinctionDocument21 pagesThe Mosaic DistinctionlucafrescobaldiNo ratings yet

- Type The Document Title: (Year)Document4 pagesType The Document Title: (Year)wubetu berihunNo ratings yet

- Chapman 2003 - Social Dimensions Mortuary PracticesDocument9 pagesChapman 2003 - Social Dimensions Mortuary PracticesDaniela GrimbergNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 EthnicityDocument48 pagesChapter 4 EthnicityAnonymous nH6Plc8yNo ratings yet

- Notes For HistoryDocument2 pagesNotes For HistoryHannah Marie CaringalNo ratings yet

- The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic MayaFrom EverandThe Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic MayaNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of History, Sources of Historical Data and Historical Criticism (Notes)Document7 pagesThe Meaning of History, Sources of Historical Data and Historical Criticism (Notes)Ebab YviNo ratings yet

- TALLBEAR, Kim. An Indigenous Reflection On Working Beyond The Human-Not HumanDocument6 pagesTALLBEAR, Kim. An Indigenous Reflection On Working Beyond The Human-Not HumanjanNo ratings yet

- Mielke CH1 History of Human ClassificationDocument22 pagesMielke CH1 History of Human ClassificationbalausaibraevaNo ratings yet

- Delaney - NomosferaDocument53 pagesDelaney - NomosferafernandombsNo ratings yet

- 4Document6 pages4Andrea MolinaNo ratings yet

- His 101 Lecture 1 Introduction To HistoryDocument46 pagesHis 101 Lecture 1 Introduction To HistoryJntNo ratings yet

- Fahlander, Oestigaard - The Materiality of Death. Bodies, Burials, Beliefs PDFDocument18 pagesFahlander, Oestigaard - The Materiality of Death. Bodies, Burials, Beliefs PDFCésar Cisternas IrarrázabalNo ratings yet

- 20 CH 15Document88 pages20 CH 15Asterios AidonisNo ratings yet

- Fowler 2010, PersonhoodDocument33 pagesFowler 2010, PersonhoodNick BlueNo ratings yet

- Citizenship Construction and The Afterlife Funeral Rituals Among Orisha Devotees in TrinidadDocument51 pagesCitizenship Construction and The Afterlife Funeral Rituals Among Orisha Devotees in TrinidadCarlene Chynee LewisNo ratings yet

- Thoreau's BodyDocument30 pagesThoreau's BodyBen RossingtonNo ratings yet

- National Curriculum Statement (NCS)Document58 pagesNational Curriculum Statement (NCS)Thandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Caps Fet History GR 10-12 WebDocument58 pagesCaps Fet History GR 10-12 WebThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Emtriva: Gilead Sciences, Inc. 1Document26 pagesEmtriva: Gilead Sciences, Inc. 1Thandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Rastafari Conference ProgrammeDocument10 pagesRastafari Conference ProgrammeThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Herb Tansy: Pharmacological Actions Tanecetumvulgare or Chrysanthemum VulgareDocument1 pageHerb Tansy: Pharmacological Actions Tanecetumvulgare or Chrysanthemum VulgareThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Death of TiroDocument23 pagesDeath of TiroThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Straight Black Pride - Operations 1Document1 pageStraight Black Pride - Operations 1Thandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Congress and The AfricanistsDocument8 pagesCongress and The AfricanistsThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Archive of The PACDocument23 pagesArchive of The PACThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Awakening of National ConsciousnessDocument283 pagesAwakening of National ConsciousnessThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- The Third Age of Artificial Intelligence: Field Actions Science ReportsDocument7 pagesThe Third Age of Artificial Intelligence: Field Actions Science ReportsThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Herb Basil: Pharmacological Actions OcimumbasilicumDocument3 pagesHerb Basil: Pharmacological Actions OcimumbasilicumThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

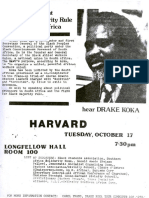

- Harvard: The Fight Blaf K Rule in South AfricaDocument1 pageHarvard: The Fight Blaf K Rule in South AfricaThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Prof PLO Lumumba ContactsDocument25 pagesProf PLO Lumumba ContactsThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Mahlubandile's New CVDocument6 pagesMahlubandile's New CVThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- DR Sebi S Product ListDocument2 pagesDR Sebi S Product ListThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Rhodes University RenamingDocument2 pagesRhodes University RenamingThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- .Letsetse April.1990Document4 pages.Letsetse April.1990Thandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Gay ManifestoDocument5 pagesGay ManifestoThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- Africa Great WarDocument8 pagesAfrica Great WarThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet

- The Historical Significance of African Liberation - The Views of South African History Education StudentsDocument12 pagesThe Historical Significance of African Liberation - The Views of South African History Education StudentsThandolwetu SipuyeNo ratings yet