Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brux I Art 2015 Consumatori

Uploaded by

Laura IpateCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brux I Art 2015 Consumatori

Uploaded by

Laura IpateCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Private International Law

ISSN: 1744-1048 (Print) 1757-8418 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rpil20

Consumer Collective Redress under the Brussels I

Regulation Recast in the Light of the Commission's

Common Principles

Beatriz Aoveros Terradas

To cite this article: Beatriz Aoveros Terradas (2015) Consumer Collective Redress under the

Brussels I Regulation Recast in the Light of the Commission's Common Principles, Journal of

Private International Law, 11:1, 143-162

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17536235.2015.1033202

Published online: 13 Jun 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 280

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rpil20

Download by: [188.4.112.111]

Date: 12 October 2015, At: 09:32

Journal of Private International Law, 2015

Vol. 11, No. 1, 143162, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17536235.2015.1033202

Consumer Collective Redress under the Brussels I Regulation

Recast in the Light of the Commissions Common Principles

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

Beatriz Aoveros Terradas*

This paper examines the state of play on cross-border consumer collective

redress in Europe in the light of three important instruments: (1) the

Brussels I Regulation (Recast) (2) the Commission Communication entitled

Towards a European Horizontal Framework for Collective Redress; and

(3) the Commissions Recommendation of 11 June 2013 on common

principles for injunctive and compensatory collective redress mechanisms in

the Member States concerning violations of rights granted under Union

Law. The study highlights general disappointment with the new European

Union instruments. The disappointment stems from the mediocre consumer

collective redress likely to be achieved by the aforementioned three

instruments.

Keywords: Collective redress mechanisms; Private International Law;

European Union Law; Consumer Law; Brussels I Regulation (Recast)

A. Introduction

Collective redress mechanisms (CRM) are fairly new in Europe compared with

other legal systems such as in the US. Nevertheless, the European Union and its

Member States have been giving the matter thought for some years now.1 Most

EU Member States have CRM2 but there are many differences between them

*Associate Professor of Private International Law at ESADE Law School Universtat

Ramon Llull. Email: beatriz.anoveros@esade.edu

1

Green Paper on Anti-Trust Actions, COM(2005)672, 19.12.2005; White Paper in 2008,

COM(2008)165, 2.4.2008; Green Paper on Consumer Collective Redress, COM(2008)

794 nal, Brussels, 27.11.2008 and White Paper on Damages Actions for Breach of the

EC Anti-Trust Rules, COM(2008) 165 nal, Brussels, 2.4.2008. Directive 98/27/EC

[1998] on injunctions for the protection of consumers interests (codied by Directive

2009/22/EC) [2009] OJ L110/30. Collective Redress in Antitrust, Directorate-General

for Internal Policies, Policy Department A: Economic and Scientic Policy, European Parliament,

2012,

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201206/

20120613ATT46782/20120613ATT46782EN.pdf (accessed 3 March 2015).

2

Commission Staff Working Document. Public Consultation: Towards a Coherent European Approach to Collective Redress, Brussels, 4th February 2011. SEC (2011) 173

nal, 3. F Cafaggi and HW Micklitz, Collective Enforcement of Consumer Law: A Framework for Comparative Assessment (2008) European Review of Private Law 391.

2015 Taylor & Francis

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

144

B.A. Terradas

and they have proved to be limited in scope and effectiveness3 (for instance,

most of the national mechanisms are generally restricted to national claims).

In 2011, the EU Commission launched a public consultation entitled Towards

a Coherent European approach to Collective Redress4 in order to identify

common legal principles of collective redress and to examine how such

common principles could t into the European Union legal systems. The European

Parliament also participated in the debate through a resolution based on an owninitiative report on collective redress.5

This consultation showed the interest in and the importance of the issue but it

also revealed how controversial the issue and the gap between consumers and

business are. Whereas consumers favour the introduction of CRM within the framework of European Union law, businesses are generally against the idea.6

It is not only collective mechanisms and their features that have been debated

but also the cross-border dimension of collective redress.7 It is well known that

several issues of private international law arise in connection with cross-border

consumer collective redress, including international jurisdiction, recognition and

enforcement, and choice of law.

This paper examines the state of play on cross-border consumer collective

redress in Europe in the light of three important instruments: (1) the Brussels

I Regulation (Recast) (henceforth BIR (Recast))8, covering amendments to the

Brussels I Regulation on jurisdiction and enforcement in civil and commercial

matters;9 (2) the Commission Communication entitled Towards a European

Horizontal Framework for Collective Redress;10 and (3) the Commissions

Recommendation of 11 June 2013 on common principles for injunctive and

compensatory collective redress mechanisms in the Member States concerning

violations of rights granted under Union Law (hereinafter Commissions Recommendation).11 The third item marks the end of a long journey begun by

S Tang, Consumer Collective Redress in European Private International Law (2011) 7

Journal of Private International Law 101, 102.

4

Commission Staff Working Document. Public Consultation: Towards a Coherent European Approach to Collective Redress, Brussels.

5

European Parliament Resolution of 2nd February 2012 Towards a Coherent European

Approach to Collective Redress.

6

Commission Communication entitled Towards a European Horizontal Framework for

Collective Redress, COM(2013) 401 nal, 11.6.2013, 6.

7

Commission Staff Working Document. Public Consultation: Towards a Coherent European Approach to Collective Redress.

8

Regulation 1215/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December

2012 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters (Recast), [2012] OJ L351.

9

Council Regulation (EC) No 44/2001 of 22 December 2000 on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters, [2001] OJ L12/1.

10

COM(2013) 401 nal, 11.6.2013.

11

[2013] OJ L201/60.

3

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

Journal of Private International Law

145

the European Union some years ago.12 These instruments aim to facilitate legal

redress for violation of EU rights and recommend that Member States have their

own CRM following the same basic principles.13 They skate over private international law issues. This is understandable given that the EU now has sole competence on the rules in this eld and thus has no need to resort to such

instruments. Nevertheless, differences between the procedural rules of the

Member States may hamper the establishment of a truly European Union area

of freedom, security and justice (Title V Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, hereinafter, TFEU) where any citizen of a Member States should

have access to the same judicial protection.14 For this reason DG JUST has

also taken part in the debate (together with DG SANCO and DG COMP).

At rst sight, none of the aforementioned instruments by itself has meant a big

change or a great step forward in solving all private international law questions at a

European Union level. Nevertheless, and as will be shown, their interdependence

necessitates making the rules of EU private international law more workable. We

shall examine the BIR (Recast) in the light of the Commissions principles to

assess the impact of the latter on the Brussels system.

B. Harmonising through common principles or seeking competition

between legal orders?

One should note that the common principles (soft law) are framed in a recommendation (which by denition is non-binding). Two burning questions arise from the

lack of statutory force. The rst concerns what the Recommendation is meant to

achieve. Is the Commission really attempting to harmonise substantive procedural

law or is it merely aiming to minimise the high cost of harmonisation (insofar as

the Member States may have different interests and/or legal traditions)? Taking

into account the Member States diversity in this eld, is the Recommendation

a breakthrough in tackling competition between legal orders or as Danov and

Becker put it merely a stab at Inter-Jurisdictional Regulatory Competition?15

Secondly, why is the Commission using a non-binding instrument?

With regard to the rst question, the Recommendation states that it aims to

facilitate legal redress for violations of rights under EU law, stop illegal practices

and enable injured parties to obtain compensation while ensuring appropriate

See a good summary in C Hodges, Collective Redress: a Breakthrough or a Damp

Squib? (2014) Journal of Consumer Policy 6789.

13

Commissions Recommendation, whereas n 10.

14

L Gorywoda, N Hatzimihail and A Nuyts, Introduction: Market Regulation, Judicial Cooperation and Collective Redress in A Nuyts (ed), Cross-Border Class Action: the European Way (Sellier European Law publishers, 2013) 155, 26.

15

M Danov and F Becker, Introduction: Centralisation (Harmonisation) or Decentralisation (Inter-Jurisdictional Regulatory Competition), in M Danov, F Becker and P Beaumont

(eds), Cross-Border EU Competition Law Actions (Hart Publishing, 2013), 97101.

12

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

146

B.A. Terradas

procedural safeguards to avoid abusive litigation.16 To this end, the Commission

recommends all Member States set up CRM following the common principles in

order to avoid malpractices and abusive litigation (something that, according to the

Commission, has happened in other legal systems such as in the US) while

respecting different legal traditions.17 An obvious question is how the application

of common principles to national CRM can be reconciled with maintaining and

respecting national legal traditions. It is important to bear in mind that some of

the Member States have already been active in this eld and, therefore, the diversity among them has already grown.18 The result could even be that this approach

to CRM through the common principles puts a spanner in successful, efcient

national redress mechanisms without doing anything to improve inefcient ones.19

The Recommendation is limited to violations of rights granted under EU

Law.20 This limitation raises an important question. Should Member States set

up a national collective system for dealing with violations of national law (assuming one does not already exist) and another for violations of EU Law? It is unclear

how this requirement would be implemented by Member States. As proposed by

Carballo, would it not have been better to have set up a facultative instrument

(such as the European Payment Order Regulation)?21 This at least would have

had the merit of showing greater respect for different legal traditions.

Furthermore, it appears that the wording of the common principles purporting

to prevent malpractices and abuses (such as punitive damages, pre-trial discovery

of documents and jury awards (see whereas 15) is tendentious.22 According to

the Commission, the principles should uphold the fundamental procedural rights

of the parties and incorporate safeguards against abuses (see whereas 13). Nevertheless, it cannot be proved that the safeguards established by the common principles will end the aforementioned abuses. As noted by Hodges, there are too

many exceptions to the safeguards provided for by the common principles.23 He

argues that What is claimed to be a solid statement of safeguards turns out on

closer inspection to be a aky, permeable and porous wall, with little stability.24

Commissions Recommendation, whereas n 10.

Commissions Recommendation, Section I, points 1 and 2.

18

C Hodges, supra n 12, see the comparison study made by this author. See as well, specically in the eld of antitrust, the study carried out by the European Parliament Collective

Redress in Antitrust, supra n 1, 1837.

19

L Carballo Pieiro, Recomendacin de la Comisin Europea sobre los principios

comunes aplicables a los mecanismos de recurso colectivo de cesacin o de indemnizacin

en los Estados miembros en caso de violacin de los Derechos reconocidos por el Derecho

de la Unin Europea (Strasbourg, 11 June 2013) (2013) Revista Espaola de derecho

internacional 2, 395, 396.

20

Commissions Recommendation, Section I, point 1.

21

Ibid.

22

Ibid.

23

C Hodges, supra n 12, 78.

24

Ibid, 79.

16

17

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

Journal of Private International Law

147

Even if most of the aforementioned abuses are foreign to European legal traditions, the main problem with regard to collective procedures seems to be their

lack of efciency and that there are too many barriers for claimants but not the

abuses that worry the Commission.25 The key questions are: (1) how the

Member States will implement the Commissions safeguards (assuming they

accept them); and (2) whether national collective redress systems will draw

closer or whether there will be greater competition among jurisdictions. If there

is competition, the jurisdiction rules set up in the BIR (Recast) will be a linchpin

in cross-border collective action insofar as they allow consumers to exercise collective action in the Member States (different from the defendants domicile) that

best meets their interests. An analysis of those rules will be conducted later.

A deeper analysis of the proposed principles may give a clue to the expected

harmonisation. The Recommendation applies both to injunctive and compensatory

relief in a horizontal way that is to say it not only addresses specic areas such as

consumers collective actions or Competition Law.26 Specic rules have been

included in a proposal for a Directive on suing for damages under national law

on infringements of competition law (Damages Directive)27 and Guidance for

national courts on quantifying harm resulting from such infringements (the Practical Guide).28 We welcome this horizontal approach because it will allow a collective mechanism that is lacking in many Member States.

The structure of the Recommendation is very simple. It is split into seven chapters: (1) purpose and subject matter; (2) denitions, common principles; (3) specic

principles relating to injunctive relief; (4) specic principles relating to compensatory collective redress; (5) general information; (6) supervision; and (7) reporting.

The common principles established by the Commission relate to standing, admissibility, information on collective redress actions, economic aspects such as the

loser pays principle, funding and lawyers fees and third-party funding. It then

establishes some specic ones for injunctive relief and compensatory collective

actions. The Commissions principles draw a CRM with an admissibility/verication phase by the competent court. Special rules of legal standing are provided in

cases of so-called representative action (both public and private entities). The

opt-in system has been chosen, requesting the express consent of the persons

25

L Carballo Pieiro, supra n 19, 396.

Some of the Member States CRM are limited to specic areas (competition and consumer protection) as in Bulgaria, Finland, France , Germany, Greece, Italy or Spain, while

others provide for a collective mechanism in all elds (UK, Denmark, Portugal Sweden

and The Netherlands). See Carballo Pieiro, supra n 19, 396.

27

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on certain rules

governing actions for damages under national law for infringements of competition law provisions of the member states and the European Union, COM(2013) 404, 11 June 2013.

28

Communication from the Commission on quantifying harm in actions for damages based

on breaches of Article 101 or 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union,

OJ C167/17, 13 June 2013.

26

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

148

B.A. Terradas

claiming to have been harmed.29 Any exception to this principle, by law or by court

order, should be based on sound administration of justice.30 The members of the

group should be free to leave the claimant party at any time.31 Injured victims

will also have the right to join the group at any time before the judgment is

given or the case settled, taking into account the need for sound administration

of justice.32 As noted earlier, contingency fees, punitive damages, pre-trial discovery of documents or jury awards are forbidden.33 Finally, a concern on the funding

leads to a deep control of it especially when it comes from a third party.

The EU strategy on collective redress is very disappointing. It aims to harmonise while respecting national legal traditions. It builds a CRM based on fear of

non-proven abuses and the need for safeguards to prevent such abuses and limit

violations of European Union Law. All these drawbacks make one sceptical of

the Recommendations impact on Member States CRM and the safeguards provided. The reason for such a mediocre result probably lies in the lack of consensus

between the various stakeholders especially between consumers and businesses

and the need for a political compromise. This reveals why the chosen instrument is

a non-binding one; there was not enough political support for anything stronger.34

C.

Brussels I Regulation (Recast) in the light of CRM common principles

The specic cross-border dimension of collective redress has always worried the

Commission.35 For this reason, Principle 17 of the Commissions Recommendation

The Member States should ensure that when a dispute concerns natural or legal

persons from several Member States, a single collective action in a single forum

is not prevented by national rules on admissibility or standing of the foreign

groups of claimants or the representative entities originating from other national

legal systems. Furthermore, it states that representative entities ofcially designated

in one Member State should be recognised in the member state with jurisdiction to

hear the collective action. The Commission Communication devotes point 3.7 to

the: Effective enforcement in cross-border collective actions through private international law rules and makes the following statements:

The general principles of European international private law require that a collective

dispute with cross-border implications should be heard by a competent court on the

29

Commissions Recommendation, point 21.

Commissions Recommendation, point 21.

31

Commissions Recommendation, point 22.

32

Commissions Recommendation, point 23.

33

Commissions Recommendation, whereas 15 and points 30 and 31.

34

According to the Communication, only ve states were in favour (Bulgaria, Greece,

Poland, Portugal and Italy but with reservations), another ve were strongly sceptical

(Austria, Czech Republic, France, Germany and Hungary). See Hodges, supra n 12.

35

Commission Staff Working Document. Public Consultation: Towards a Coherent European Approach to Collective Redress, Brussels, 4 February 2011. SEC (2011) 173 nal, 6.

30

Journal of Private International Law

149

basis of European rules on jurisdiction, including those providing for a choice of

court, in order to avoid forum shopping. The rules on European civil procedural

law and applicable law should work efciently in practice to ensure proper co-ordination of national collective redress procedures.

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

The Commission considers that the existing rules of the BIR (Recast) should be

fully exploited. One can reasonably infer from the statement that no amendments

on jurisdiction and enforcement are expected in the near future, contrary to the

views expressed and proposals made by some writers.36 This paper analyses

whether a specic rule on jurisdiction for consumer collective redress actions

could be established through CJEU interpretation of the current BIR (Recast) in

the light of its case-law and the proposed common principles.

1.

Jurisdiction rules

In collective consumer redress cross-border cases, the rst issue that arises is the

international jurisdiction. As noted earlier, the BIR (Recast) has not made major

changes to the jurisdiction rules. The revision of the jurisdiction rules was a

golden opportunity to introduce a special rule for collective actions as some

scholars proposed37 but unfortunately it was missed. Such an opportunity will

not arise again in the near future.

On the contrary, the only amendment worth highlighting in this connection is the

change of the geographical scope of Section 4 of Chapter II dealing with jurisdiction

over consumer contracts. Under Regulation 44/2001, that section only applies if the

defendant is domiciled in a Member States; according to Regulation 1215/2012 the

section will be applicable regardless of the defendants domicile. Article 18(1) of

the BIR (Recast) would therefore allow EU consumers to sue third-State suppliers

in the courts of the Member States of the consumers domicile. The main purpose

of this reform is to ensure protection for EU consumers. It should however be

borne in mind that in connection with compensatory actions, such protection will

only be effective if the supplier owns property in a Member States since such judgments will probably not be recognised outside the EU. 38

None of the jurisdiction rules provided for in the BIR (Recast) is particularly

designed for collective redress. In fact, the Regulation rules were largely conceived for two-party proceedings. Article 8(1) deals with proceedings where

there are several defendants but, as Lein points out, there is doubt as to its potential

application by analogy to cases of plurality of claimants especially due to the

C Gonzalez Beilfuss and B Aoveros Terradas, Compensatory Consumer Collective

Redress and the Recast Brussels I Regulation, in A Nuyts (ed) Cross-Border Class

Action: the European Way (Sellier European Law publishers, 2013) 24158.

37

S Tang, supra n 3, 101; C Gonzalez Beilfuss and B Aoveros Terradas, supra n 36, 241.

38

C Gonzalez Beilfuss and B Aoveros Terradas, supra n 36, 241.

36

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

150

B.A. Terradas

exceptional character of Article 8(1) of the BIR (Recast).39 The jurisdiction system

established by the BIR (Recast) creates several different heads of jurisdiction,

sometimes based on the type of action in question (contracts, torts), sometimes

on general jurisdiction rules, such as the defendants domicile or party autonomy.

The suitability of the different grounds of jurisdiction with regard to consumer collective redress claims is a complex question that varies depending on the characterisation of the action in question. In fact there are several grounds for jurisdiction

which a consumer redress action could t: general jurisdiction based on the defendants domicile; consumer contract protection rules and the special fora provided

for in matters relating to contract and in matters relating to tort.

The Commissions Recommendation introduces autonomous procedural denitions that may have an impact on the BIR (Recast) and the characterisation of the

action in question and therefore on the applicable jurisdiction rule.

(a) Characterisation

As denounced by some scholars, Neither in the European Union Member States

nor at the European level, is there any coherent denition of collective redress.40

Therefore, the denitions introduced by the European Union instrument were

needed to identify the framework of European Union action. According to the

Recommendation, collective redress means:

(i) a legal mechanism that ensures a possibility to claim cessation of illegal behaviour collectively by two or more natural or legal persons or by an entity entitled to

bring a representative action (injunctive collective redress); (ii) a legal mechanism

that ensures a possibility to claim compensation collectively by two or more

natural or legal persons claiming to have been harmed in a mass harm situation or

by an entity entitled to bring a representative action (compensatory collective

redress).41

Two main types of compensatory collective redress actions can be distinguished. First, the so-called group action, in which dened claimants (two or

more natural or legal persons) bring actions in a single procedure to enforce their

similar claims together, with each group member being a party in the proceedings.

E Lein, Cross-Border Collective Redress and Jurisdiction under Brussels I, in D Fairgrieve and E Lein (eds), Extra-territoriality and Collective Redress (Oxford University

Press, 2012) 129, 141. It has nevertheless been used by the Amsterdam Court of Appeal

in the Royal Dutch Shell case of 29 May 2009 (NJ [2009] 506) and on the Convenium settlement cases, Preliminary Ruling Court of Appeal, 12 November 2010, LJN: BO3908 and

Court of Appeal of Amsterdam of January 2012, LJN:BV1026 (quoted and explained by

E Lein). See as well B Hess, A Coherent Approach to European Collective Redress, in

D Fairgrieve and E Lein (eds), Extraterritoriality and Collective Redress (Oxford University Press, 2012) 1134.

40

Hess, supra n 39, 108.

41

Commissions Recommendation, Section II point 3 letter (a).

39

Journal of Private International Law

151

Secondly, there are the so-called representative actions dened by the Commission Recommendation as:

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

An action which is brought by a representative entity, an ad hoc certied entity or a

public authority on behalf and in the name of two or more natural or legal persons

who claim to be exposed to the risk of suffering harm or to have been harmed in

a mass harm situation whereas those persons are not parties to the proceedings.42

The main difference between those mechanisms is the person/persons who may

bring an action and the type of interest they defend. In the case of representative

actions, a new litigating relationship is created between the plaintiff (certied

entity or a public authority) and the defendant. The interests at stake are at least

partly public. Group actions are actions with multiple claimants. They protect

mainly individual interests.

In the case of a representative action, even if the current case-law of the CJEU

with regard to the interpretation of Section 4 of Brussels I seems to favour a restrictive interpretation rather than a teleological one (which led some to argue that the

protective fora cannot be extended to representative actions),43 some writers have

suggested otherwise when a consumer association brings the action.44 The relevant factor should be the lack of bargaining power and the weaker position of

the person who brings the action vis--vis the other party. In relation to the standing needed to bring a representative action, the common principles established by

the Commissions Recommendation state that Member States should designate

representative entities on the basis of clearly dened conditions of eligibility.

This means that, at the very least, (a) the entity should be of a non-prot nature;

(b) there should be a direct relationship between the main objectives of the

entity and the alleged violations of rights granted under EU Law; and (c) the

entity should have sufcient capacity in terms of nancial resources, human

resources and legal expertise.45 The need to demonstrate that all these conditions

are met makes it clear that the entities bringing the action do not need special jurisdictional protection rules to offset their weakness.

Other important denitions are: mass harm situation, meaning a situation

where two or more natural or legal persons claim to have suffered harm causing

damage resulting from the same illegal activity of one or more natural or legal

42

Commissions Recommendation, Section II point 3 letter (d).

Case C-89/91, Shearson Lehman Hutton Inc v TVB Treuhandgesellschaft fr Vermgensverwaltung und Beteiligungen mbH, [1993] ECR I-139. See C Gonzalez Beilfuss and B

Aoveros Terradas, supra n 36.

44

L Carballo, Las acciones colectivas y su ecacia extraterritorial. Problemas de recepcin

y trasplante de las class actions en Europa (Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, 2009)

107; P Jimnez, El tratamiento de las acciones colectivas en materia de consumidores en el

Convenio de Bruselas (2003) La Ley, 157383

45

Commissions Recommendation, Section III, points 4, 5 and 6.

43

152

B.A. Terradas

persons;46 and action for damages, meaning an action by which a claim for

damages is brought before a national court.47 Both concepts use the word

damage in a broad sense covering both contract and tort actions. In fact, the

Spanish version, for instance refers to accin de daos y perjuicios covering

contractual and extra-contractual remedies. Therefore, depending on the action

in question, the heads of jurisdiction on matters relating to a contract and in

matters relating to delict and quasi-delict can apply.

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

(b)

Heads of jurisdiction and multiple defendants

There are differing views on the right jurisdictional rules for consumer collective

redress. As the Commission explains in its Communication, a rst group of stakeholders advocate a new rule giving jurisdiction in mass claim situations to the

court where the majority of the allegedly injured parties are domiciled and/or an

extension of the jurisdiction for consumer contracts to representative entities

bringing a collective claim.48 This rst proposal raises several questions, most

of them already highlighted by scholars.49

Depending on the action in question (consumer contracts, contracts, torts)

different special heads of jurisdiction could t a collective consumer redress

action. The analysis carried out above on the potential application of the consumer

protection rules of Section IV of the BIR (Recast) to representative actions shows

that the option of extending those rules to claims brought by those entities is

hardly practicable. May the special fora in matters relating to a contract or

matters relating to tort be used to allocate jurisdiction in mass claim situations

to the court where most of the parties who claim to have been injured are domiciled?

The main difculty will arise when there is a plurality of consumers (claimants)

having their domicile in different Member States.50 The CJEU has supported

looking at the centre of gravity of the claimant in online speech torts in order to

cut down the number of courts that may have jurisdiction.51 Nevertheless, as

46

Commissions Recommendation, Section II, points 3, letter (b).

Commissions Recommendation, Section II, points 3, letter (c).

48

Commissions Communication, point 3.7.

49

S Tang, supra n 3 102; B Hess supra n 39, 108. A Nuyts, The Consolidation of Collective Claims Under Brussels I, in A Nuyts (ed), Cross-Border Class Action: the European

Way (Sellier European Law Publishers, 2013) 69, 83; C Kessedjian, Le droit entre concurrence et co-operation, in Vers de nouveaux quilibres entre les orders juridiques Liber

Amicorum H. Gaudemet-Tallon, (2005), 129.

E Lein, supra n 39, 141; D Tzakas, Effective Collective Redress in Anti-trust and Consumer Protection Matters: Panacea or Chimera? (2011) 48 Common Market Law Review

(2011) 1125.

50

The same issue arises when applying Section 4 to a group action and there is a multiplicity

of consumers with domiciles in different Member States,

51

See Cases C 509/09 and C 161/10, eDate Advertising GmbH and Olivier Martinez/Robert

Martinez [2011] ECR I-10269.

47

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

Journal of Private International Law

153

explained elsewhere with Professor Gonzlez Beilfuss,52 the use of the interpretation given by the CJEU concerning the application of the special fora53 when

there are several places of delivery, several places of provision of services or

several places where the harmful event occurred, raises tricky issues that sit ill

with the CJEUs recent interpretation. National courts are encouraged to identify

one of the places of performance of the obligation at issue as the principal one

and assert jurisdiction in that place. In Color Drack,54 for instance, the CJEU

ruled that where goods are delivered in several places in one Member State

(cases of micro-multiplicity),55 the court of the main place of delivery is entitled

to hear all claims. In order to dene the principal place of delivery, economic criteria

should be used. When this is not possible, the claimant is entitled to choose where to

sue. Where services are provided or goods delivered in several places in different

Member States (cases of macro-multiplicity) this principle may not always work.

In its decision in Air Baltic,56 concerning the carriage of passengers by air, the

CJEU was unable to identify either the place of departure or the place of arrival

as the main place of provision of the services. Both the place of departure and the

place of arrival had sufcient connections. It was then the plaintiffs decision

whether to sue in either of those places. In Wood Floor57 there were more than

two places of provision of services and the court held that the place where the

main services are provided has jurisdiction to determine all claims arising from

the contract. In the Wood Floor case, the contract was a commercial agency contract

and the court held that the place where the main services were provided was the main

place where the agent provided the services. This is determined by analysing

whether the contract denes the main place where the agent should provide the services, failing that the main place where the agent in fact provided the services (provided he did not act contrary to the terms of the contract in doing so) or, failing that,

where the agent is domiciled.58

Can the principle of centre of gravity be extended to consumer compensatory

collective redress? In the case of a group action under Article 18 of the BIR

(Recast), discrimination is the main problem that may arise. Section 4 of

Chapter II of the BIR (Recast), especially Article 18, aims to protect the consumer

52

In this section, I am following the reasoning we (Prof Gonzalez and I) used in our article C

Gonzalez Beilfuss and B Aoveros Terradas, supra n 36.

53

See C Or Martnez, El artculo 5.1.b) del Reglamento Bruselas I: examen crtico de la

jurisprudencia reciente del Tribunal de Justicia (2013) 2 In Dret, 124.

54

Case C-386/05, Color Drack Gmb v Lexx International Vertriebs GmbH [2007] ECR I3699.

55

Term used by A Briggs and P Rees, Civil Jurisdiction and Judgments (5th ed, Informa,

2009) 234.

56

Case C-204/08, Peter Rehder v Air Baltic Corporation [2009] ECR I-6073.

57

Case C-19/09, Wood Floor Solutions v Silva Trade SA [2010] ECR I-2121, at paras 24

29.

58

Paragraphs 3842. See the critique of this case by P Beaumont and P McEleavy, Private

International Law: Anton (SULI, 3rd ed, 2011) 305.

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

154

B.A. Terradas

by giving him the option of suing in the jurisdiction of his domicile. If the national

court has to identify one of the consumers domiciles as the centre of gravity of the

collective action in question, the consumers whose domiciles have not been

chosen may feel that they have been discriminated against (they are bereft of protection). Furthermore, which criteria should the national court use to decide which

consumers domicile is the centre of gravity? Will it depend on the number of consumers?59 If so, what is the threshold? Does a numerical criterion comply with the

teleological interpretation followed by the CJEU when interpreting Section IV of

the BIR (Recast)?60 Even if there is a forum where most of the consumers have

their domicile which could be identied as the centre of gravity, the principle of

non-discrimination must lead us to dismiss this interpretation. It is therefore difcult to accept the suitability of Article 18 of the BIR (Recast) when consumers

domiciled in different Member States are involved in the collective action.

In a representative action brought under Article 7(1) of the BIR (Recast), the

place of delivery of the goods or the place where the services have been provided

will often coincide with the place of the consumers domicile.61 In this case, is it

possible to apply the centre of gravity doctrine laid down by the CJEU to identify one court with jurisdiction over the whole claim? The special jurisdiction

ground in Article 7(1) of the BIR (Recast) is based on the principle of proximity.

Under this principle there is no problem in identifying the closest court or the

centre of gravity of the action in question. The main difculty in the case of a collective action is that there are several contracts with one place of performance each

(instead of one contract with several places of performance). As has been pointed

out, Where there are two contracts, it is doubtful that proceedings can be brought

at the place of performance of a given contract, even if the legal and factual issues

are the same.62 Following this interpretation it is doubtful whether Article 7(1) of

the BIR (Recast) allows aggregation of all the contract claims before the place of

performance of one of them.63 The wording of Article 7(1) suggests that jurisdiction is provided for each individual contract. It could, nevertheless, allocate claims

that relate to several contracts which happen to have the relevant place of performance in the same Member States.

However, it could be decided that there are several courts with potential jurisdiction over the contractual claims that have a connection with the forum. The contractual claim is divided and the Shevill principle64 of strict proximity is extended

to compensatory consumer collective redress actions. There are no advantages in

59

S Tang, supra n 3, 142.

See for example Case C89/91 Shearson Lehamn Hutton v TVB Treuhandgesellschaft fr

Vermgensverwaltung und Beteiligungen GmbH [1993] ECR I139 point 13; Case C269/

95 Benincasa v Dentalkit Srl [1997] ECR I3767.

61

Tang, supra n 3, 140.

62

Nuyts supra n 49.

63

Ibid.

64

Case C-68/93 Shevill v Presse Alliance SA [1995] ECR I-415.

60

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

Journal of Private International Law

155

this solution since there will be several collective actions and not a pan-European

collective action against the defendant.

In the case of a cross-border tort, Article 7(2) of the BIR (Recast) should be

applicable. Following the CJEU canons of construction with regard to this provision, the class claimants may choose between bringing the action before the

courts where the causal event occurred (with wider jurisdiction) or before the

courts where the damage was rst inicted. In the rst case, the seised court will

have jurisdiction for the entire damage inicted and it will generally coincide

with the establishment of the tortfeasor (ergo generally the court of the domicile

of the defendant).65 In the second case, the seised court has jurisdiction limited to

the damages that occurred in its territory (the Shevill principle). The problem

which arises again is the case where the damage is inicted in several Member

States usually because the victims are domiciled in different Member States. Is

there a way to unify all tort claims in one court? As some authors argue, the new

CJEU case law in e-Date Advertising/Martinez66 may allow all the damages to

be claimed at the place of the centre of interests of the collective injured

parties.67 The new connecting factor place of the centre of interests of the

victim has been developed by the CJEU in the e-Date Advertising/Martinez case

with regard to an infringement of personality rights on the internet. In such a

case, the CJEU stated that jurisdiction would be possible either at the place

where the website can be accessed, but only for the harm caused in that Member

States (the Shevill principle), or for all the damages at the place where the

alleged victim has his centre of interests.68 According to the CJEU, the place

where a persons interests are centred is generally that of his habitual residence.

However, a person may also have the centre of his interests in a Member States

in which he does not habitually reside, insofar as other factors, such as the

pursuit of a professional activity, may establish the existence of a particularly

close link with that State.69 Is it possible to extend this connecting factor to a consumer class action where there are victims from different Member States? In such a

case, what would the injured parties centre of interests be? Would it be possible to

consider that the centre of interests is the place where most of the victims have their

habitual residence or even the jurisdiction whose CRM protect them best? The

answer to these questions is far from easy taking into account the reasoning of

A Nuyts, Suing at the Place of Infringement: The Application of Article 5(3) of Regulation 44/2001 to IP Matters and Internet Disputes, in N Hatzimihail, A Nuyts and K Szychowska (eds), International Litigation in Intellectual Property and Information

Technology (2008, Kluwer Law International) 105, 11821. See also A Nuyts, supra n 49.

66

Cases C-509/09 and C-161/10, eDate Advertising GmbH and Olivier Martinez/Robert

Martinez [2011] ECR I-10269.

67

A. Nuyts, supra n 49, 76.

68

Cases C-509/09 and C-161/10, supra n 67, para 52.

69

Ibid, para 49.

65

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

156

B.A. Terradas

the CJEU and the aim of predictability of the rules governing jurisdiction,70 ensuring sound administration of justice and effective conduct of proceedings. Furthermore, in the Wintersteiger71 case the CJEU refused to extend the application of

the connecting factor centre of interests of the victim to online infringement of

national trademarks, basing the refusal on the principle of the territoriality of

national trademarks.

According to other stakeholders, jurisdiction at the place of the defendants

domicile is the most appropriate since it is easily identiable and ensures legal

certainty.72 Even if the objective benets of such a forum are agreed (especially

in terms of legal certainty a principle highlighted by the new European Union

instruments), it also greatly benets corporations since they would always be

defending the class action at home. It has nevertheless, a great disadvantage

for the potential consumers insofar as they would always have to face the

cost and difculties of litigating abroad.73 Here, it is hard to reconcile both principles: legal certainty and the necessary consumer protection both stated

objectives in the Commissions Recommendation.

A third category of stakeholders suggests creating a special judicial panel for

cross-border collective actions within the CJEU.74 This proposal has been ditched

given that the aim of the common principles is to set up minimum harmonisation

standards of justice for different national CRM.

Therefore, the main drawbacks with regard to the existing rules on jurisdiction within the BIR (Recast) still need to be overcome but this will have to be

done through the interpretation of the heads of jurisdiction laid down in the BIR

(Recast). The risk of parallel proceedings will probably rise (given the difculties in concentrating all actions in one court apart from the defendants domicile)

and thus the scope for irreconcilable rulings. Nevertheless, as rightly observed

by Tzakas:

This situation constitutes an optimal balance of the parties interests since on the one

hand it prevents forum-shopping or vexatious jurisdictional practices and on the

other hand it offers to the victims an alternative to the exclusive jurisdiction of the

courts where the defendants seat is located.75

In such a case the rules on lis pendens should apply in order to avoid irreconcilable

decisions. Nevertheless, the BIR (Recast) lis pendens rules have not been adjusted

70

See eg Case C-144/10 BVG [2011] ECR I-3961, para 33.

Case C-523/10, Wintersteiger AG v Products 4U Sondermaschinenbau GmbH ECLI:EU:

C:2012:220 especially paras 249.

72

Commissions Communication, point 3.7.

73

Nuyts, supra n 49. DPL Tzakas, supra n 49, 11558.

74

Commissions Communication, point 3.7.

75

DPL Tzakas, supra n 49, 1163.

71

Journal of Private International Law

157

to collective actions and may cause several problems, analysis of which goes

beyond the scope of this paper.76

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

2. Enforcement

A key element in the Commission Proposal on the BIR (Recast) was the full abolition of exequatur.77 Nevertheless, such abolition was underpinned by the premise

of mutual trust and for that reason the Proposal maintained the exequatur proceeding in some areas where there was a lack of harmonisation. Article 37 of the Proposal excluded some collective actions because of the lack of mutual trust. Article

37(3)(b) reads as follows:

(b) in proceedings which concern the compensation of harm caused by unlawful

business practices to a multitude of injured parties and which are brought by

i. a State body,

ii. a non-prot organisation whose main purpose and activity is to represent

and defend the interests of groups of natural or legal persons, other than

by, on a commercial basis, providing them with legal advice or representing them in court, or

iii. A group of more than twelve claimants.

Leaving aside the various questions that this rule begs, one should highlight

the Commissions belief that some of the collective actions were excluded by

the abolition of exequatur due to the lack of harmonisation.78 This means that a

certain degree of harmonisation of collective redress procedures is necessary to

go a step further in the process of the abolition of exequatur. In this sense the

approximation of the laws of the Member States (if achieved) in accordance

with the aforementioned principles will have considerable impact since harmonisation of substantive law underpins the principle of mutual trust.79

76

See an analysis with regard to competition actions in M Danov, Jurisdiction in CrossBorder EU Competition Law Cases: Some Specic Issues Requiring Specic Solutions,

in M Danov, F Becker and P Beaumont (eds), Cross-Border EU Competition Law

Actions (Hart Publishing, 2013) 167, 18694.

77

See an exhaustive analysis of the provisions on collective redress by the Proposal for a

Brussels I Recast in L Carballo Pieiro, Collective Redress in the Proposal for a Brussels

I Regulation: A Coherent Approach? (2012) 2 Journal of European Consumer and Market

Law 8194. See as well with regard to competition law, P Beaumont, Abolition of Exequatur under the Brussels I Regulation as it Affects EU Competition Law, in M Danov, F

Becker and P Beaumont (eds), Cross-Border EU Competition Law Actions (Hart Publishing, 2013), 37183; S Bariatti, The Recognition and Enforcement in the EU of Foreign

Judgments in Anti-Trust Matters: The Case of US and Dutch Judgments and Settlements

Rendered upon Class Actions, in M Danov, F Becker and P Beaumont (eds) CrossBorder EU Competition Law Actions (Hart Publishing, 2013) 38597.

78

See an analysis of this article in L Carballo Pieiro, supra n 80, 85.

79

Ibid, 82.

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

158

B.A. Terradas

In fact, the BIR (Recast) makes no such distinction. The reason for this change

might be twofold: (a) the nal idea of abolition of exequatur is far from the one

designed in the Proposal. Despite, the Commissions Proposal to the contrary, the

Recast has retained the possibility for refusal of enforcement (the control of the

foreign judgment will take place in the actual enforcement proceedings); and (b)

a horizontal approach has been nally settled upon so, on the one hand, it makes

no sense to distinguish between different collective actions depending on the

elds as the Proposal did and, on the other, there will be harmonisation of

minimum standards in the EU.

Although Article 39 of the Recast provides that A judgment given in a Member

State which is enforceable in that Member State shall be enforceable in the other

Member States without any declaration of enforceability being required it then

allows for a control of the decision in the addressed Member States in the actual

enforcement procedure on the EU grounds in Article 45 of the BIR (Recast). This

means that enforcement of the judgment may still be refused on the same

grounds as those in Articles 34 and 35 of the Brussels I Regulation but aggregated

in one provision.

Many questions arise at this point with regard to the different grounds for nonenforcement of a class action decision.80 This paper concentrates on the key

ground for non-enforcement: the public policy exception and the impact of

some of the common principles in it. Little consideration of other grounds for

non-enforcement will be given for want of space.

The Recast has not adapted the grounds for non-enforcement to the features of

collective actions where the rights of the putative claimants are of great importance. The Recast Brussels I Regulation only takes into account the defendants

due process rights.

(a)

Public policy ground for refusal

The scope and content of public policy is crucial. The meaning of this concept is to

be determined by reference to the law of the State where enforcement is sought.

Thus the approximation of the laws of the various Member States should have

an impact on this concept. Further, as held by the CJEU,81 the limits or parameters

of public policy depend on European Union Law. Therefore, the common principles will also have a signicant impact on those limits.

As noted earlier, the Commission clearly chose the opt-in principle. Any exception to this principle, by law or by court order, should be duly justied by reasons of

80

Very frequently, collective proceedings end with a court settlement. The Recast Brussels I

Regulation maintains the public policy control which is very important with regard to collective redress settlements since they raise many due process questions.

81

Case C-7/98 Krombach [2000] ECR I-1935, para 23; Case C-394/07 Gambazzi [2009]

ECR I-2563, Case C-619/10, Trade Agency ECLI:EU:C:2012:531, para 69.

Journal of Private International Law

159

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

sound administration of justice. Must decisions taken in an opt-out proceeding justied under the Commissions exception be enforced in all Member States and may it

not be refused on public policy grounds?

Other important elements as to the construction of the limits of the public

policy ground for refusal of enforcement may be found in the following

common principles: (a) prohibition of contingency fees, (b) prohibition of punitive

damages; and (c) controlled funding of third parties.82 They all tend to avoid

dangerous malpractices common in other jurisdictions such as the US. Nevertheless, a deeper analysis of such practices and the consequences of forbidding them

would have been desirable.

The Common principles set up the traditional restitution in integrum since, as

the Communication explains:

the punishment and deterrence functions should be exercised by the public authorities. There is no need for EU initiatives on collective redress to go beyond the

goal of compensation: Punitive damages should not be part of a European collective

redress system.83

Therefore, according to the Commissions Recommendation, the compensation awarded to the victims in cases of mass harm should not exceed the compensation they would have been awarded had the claim had been pursued by

means of individual actions. In particular, punitive damages, leading to over-compensation in favour of the victim, should be prohibited (point 31). Is this prohibition an ofcial recognition of punitive damages as a category contrary to the

public policy of the Member States (or even contrary to EU public policy)? If

so, does it mean that a judgment awarding punitive damages may not be recognised

in another Member States? If this is the case, will this interpretation be extended to

third-country decisions awarding punitive damages? This is an important question

since there are at least three Member States that allow for these damages in

certain elds (Ireland, UK and Cyprus).84 Further, the CJEU in Manfredi held

that punitive damages should be awarded for breach of EU competition law in a

private damages action when such damages are available in the equivalent domestic

82

B Vil Costa and C Or Martnez, Comments to the White Paper on Damages Actions

for Breach of the EC Anti-Trust Rules, in http://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/

actionsdamages/white_paper_comments/unibar_en.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2015).

83

Point 3.1.

84

M Danov, Awarding Exemplary (or Punitive) Antitrust Damages in EC Competition

Cases with an International Element The Rome II Regulation and the Commissions

White Paper on Damages (2008) 29 European Competition Law Review 430, 4345; J

Carrascosa Gonzlez, Daos Punitivos. Aspectos de Derecho internacional privado

europeo y espaol, in M J Herrador Guardia (ed), Derecho de Daos (2013, Aranzadi)

383, 464, quoting J Rodrguez Rodrigo, Aplicacin privada del Derecho de competencia,

in A L Calvo Caravaca and J Carrascosa Gonzlez (eds) Derecho del comercio internacional (Cole, 2012) 1417, 1473.

160

B.A. Terradas

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

competition law actions.85 Finally, some EU Member States have allowed non-compensatory damages through the enforcement of third-State judgments. This is the

case for France86 and the Spanish Supreme Court is in favour of the recognition

of a foreign judgment granting punitive damages if it passes the following three

tests: (1) the amount of punitive damages granted by the foreign judgment is not

excessive; but (2) if the damages are excessive they still can be recognised if

there are special circumstances that warrant the damages awarded; and (3) there

is a weak link between the situation and Spain.87 This trend for the recognition of

foreign judgments clashes with the above-mentioned prohibition established in

the Commissions Recommendation.

(b) When the judgment was given in default of appearance, if the defendant was

not served appropriately

This ground for refusing to enforce the collective redress judgment concerns the procedural protection of the defendant. Within the collective redress proceedings it is

also very important to guarantee the claimants procedural rights. For instance, as

Carballo points out When economic rights are at stake, it seems logical to give

them [the claimants] at least the opportunity to intervene, i.e. they must receive

notice of the collective proceedings and the right either to include themselves (optin) or exclude themselves (opt-out).88 On the contrary, where the economic

claims of each member are so small that they are not worth being pursued in

court, legislators are laying down representative collective actions, in which the safeguard of group members due process rights relies on the adequacy of their representation, not in being notied and granted the right to opt out/opt in.89

Nevertheless, the BIR (Recast) does not take into account the need for such

protection. How can the rights of the putative claimants be protected and guaranteed?90 Again, the Common principles set up rules on the need for information on

a collective redress action. Principle 10 requires the Member States to allow the

representative or the group of claimants to disseminate information about a

claim violation of EU rights and their intention to seek an injunction or to

pursue an action for damages. Nevertheless, Principle 11 limits such an obligation

since the dissemination methods should take into account the particular circumstances of the mass harm, freedom of expression, the right to information, and

85

Case C-295/04 and C-298/04, [2006] ECR I-6619, para 99.

Cour de Cassation 1 December 2010.

87

J Carrascosa Gonzlez, Daos Punitivos. Aspectos de Derecho internacional privado

europeo y espaol, in M J Herrador Guardia (ed) Derecho de Daos (2013, Aranzadi)

383, 453. See for instance ATS 13 November 2001.

88

L Carballo Pieiro, supra n 76, 88. R Fentiman, Recognition, Enforcement and Collective Judgments, in A Nuyts (ed), Cross-Border Class Action: the European Way (Sellier

European Law publishers, 2013) 85110, 93.

89

Ibid.

90

R. Fentiman, supra n 87, 91.

86

Journal of Private International Law

161

protection of the value of the defendant companys reputation before its responsibility for the alleged violation or harm is established by the nal judgment of the

court. As Carballo points out, at this stage the collective action is already ongoing,

making such control unnecessary.91

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

(c)

Irreconcilability grounds and the risk of parallel collective proceedings

These grounds are of course potentially applicable, raising questions where the class

of parties is not identical. Article 45(1)(c) of the BIR (Recast) requires both judgments to be given between the same parties for the judgments to be considered irreconcilable. Special difculties could arise when one of the members of the group

has begun an individual claim which has been decided at the time of the enforcement

proceedings. The duality maintained by the Commissions Recommendation raises

questions as to the scope of the term parties and issues regarding lis pendens.

Furthermore, there is a high risk of parallel collective proceedings given the

foreseeable difculties in centralising the collective litigation by multiple claimants in a single national court.92 As seen, the BIR (Recast) has not adapted

the lis pendens rules to collective redress proceedings and thus is likely to increase

the chances of irreconcilable judgments.93

D.

Concluding remarks

This paper highlights general disappointment with the new European Union instruments. The disappointment stems from the mediocre consumer collective redress

likely to be achieved by the aforementioned three instruments. First, the BIR

(Recast) has not explicitly taken into account collective redress in terms of jurisdiction. Furthermore, nothing has been done to adapt procedural mechanisms. Secondly,

the Commissions Recommendation on the common principles limits its scope in a

way that will make consumer collective redress even less harmonised and more

complex than it is now. The Commission seems more worried about blocking unproven illegal practices than about establishing a worthwhile European Union consumer

collective redress system. The choice of a non-binding instrument is a clear symptom

of the lack of consensus and corporate fear of the collective mechanisms seen in other

jurisdictions. That said, it is true that the harmonisation of the laws of the Member

States in CRM is needed to achieve a truly European Union access to justice in

cases justifying collective action. Unication of substantive and private international

law rules is the only way to create a European Union redress mechanism. Nevertheless, setting up common principles through a non-binding instrument is not the way

to achieve the desired approach. Time will tell how the States (if they do it)

91

L Carballo Pieiro, supra n 19, 398.

See the analysis in point 1(b).

93

DPL Tzakas, supra n 49, 1156.

92

162

B.A. Terradas

implement the common principles and whether harmonisation is achieved given the

tendency for Member States to want to maintain their own legal traditions. Meanwhile, the CJEU will have to interpret the BIR (Recast) in a way that honours

both the principle of consumer protection and the principle of legal certainty (thus

improving the workings of the internal market).

Acknowledgement

Downloaded by [188.4.112.111] at 09:32 12 October 2015

The research done for the publication of this article was carried out thanks to the nancial

aid given by lObra Social la Caixa.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- H1 Impact TradusDocument4 pagesH1 Impact TradusLaura IpateNo ratings yet

- G.G. Evaluation PlanDocument3 pagesG.G. Evaluation PlanLaura IpateNo ratings yet

- G.G. Evaluation PlanDocument3 pagesG.G. Evaluation PlanLaura IpateNo ratings yet

- Consumer Protection and Rome 1 Art 2015Document21 pagesConsumer Protection and Rome 1 Art 2015Laura IpateNo ratings yet

- Data Protection Regulation Art 2015Document19 pagesData Protection Regulation Art 2015Laura IpateNo ratings yet

- Compulsory Licensing in Eu Art 2013Document37 pagesCompulsory Licensing in Eu Art 2013Laura IpateNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Digest Eland PhilsDocument3 pagesDigest Eland PhilsKevin KhoNo ratings yet

- Manalo V de MesaDocument7 pagesManalo V de Mesadayneblaze100% (1)

- Hun Hyung Park vs. Eung Won ChoiDocument14 pagesHun Hyung Park vs. Eung Won ChoiMaria Nicole VaneeteeNo ratings yet

- J 1468-2230 1968 tb01206 XDocument31 pagesJ 1468-2230 1968 tb01206 XMacDonaldNo ratings yet

- [G.R. No. L-10128. November 13, 1956.] MAMERTO C. CORRE, Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. GUADALUPE TAN CORRE, Defendant-Appellee. _ NOVEMBER 1956 - PHILIPPINE SUPREME COURT JURISPRUDENCE - CHANROBLES VIRTUAL LAW LIBRARYDocument3 pages[G.R. No. L-10128. November 13, 1956.] MAMERTO C. CORRE, Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. GUADALUPE TAN CORRE, Defendant-Appellee. _ NOVEMBER 1956 - PHILIPPINE SUPREME COURT JURISPRUDENCE - CHANROBLES VIRTUAL LAW LIBRARYWeddanever CornelNo ratings yet

- In Court and in ChambersDocument9 pagesIn Court and in ChambersGerrit TimmermanNo ratings yet

- EUGENIA LICHAUCO PARTNERSHIP DISSOLUTIONDocument2 pagesEUGENIA LICHAUCO PARTNERSHIP DISSOLUTIONNerissa BalboaNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contracts NotesDocument5 pagesObligations and Contracts NotesyenNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Shareholder Rights Highlights Key DifferencesDocument14 pagesComparison of Shareholder Rights Highlights Key DifferencesSougata Kundu100% (1)

- ObliCon Compilation of Doctrines and Case DigestsDocument249 pagesObliCon Compilation of Doctrines and Case DigestsJohn Lester LantinNo ratings yet

- New Civil Code Provisions (Agency)Document6 pagesNew Civil Code Provisions (Agency)Maan ElagoNo ratings yet

- BVI Business Companies Act 2004 Conyers PDFDocument226 pagesBVI Business Companies Act 2004 Conyers PDFJuliani HanlyNo ratings yet

- Tanguilig Vs CADocument1 pageTanguilig Vs CAMickey Ortega100% (3)

- People v. HolgadoDocument1 pagePeople v. HolgadoJames Erwin Velasco100% (1)

- Act of The ChildDocument13 pagesAct of The ChildAnand YadavNo ratings yet

- Agripino Brillantes and Alberto B. Bravo For Plaintiffs-Appellants. Ernesto Parol For Defendants-AppelleesDocument20 pagesAgripino Brillantes and Alberto B. Bravo For Plaintiffs-Appellants. Ernesto Parol For Defendants-AppelleesJerald BautistaNo ratings yet

- Business Law Assignment PDFDocument4 pagesBusiness Law Assignment PDFamit90ish100% (1)

- RTC annuls sale of conjugal property due to forged husband's consentDocument8 pagesRTC annuls sale of conjugal property due to forged husband's consentArnaldo DomingoNo ratings yet

- Administrative Discretion ExplainedDocument60 pagesAdministrative Discretion ExplainedTanuja KorajkarNo ratings yet

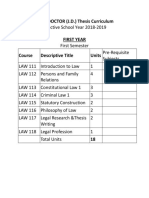

- JURIS DOCTOR (J.D.) Thesis CurriculumDocument10 pagesJURIS DOCTOR (J.D.) Thesis CurriculumleonNo ratings yet

- 8101 - Contract 2 - Semester 8Document5 pages8101 - Contract 2 - Semester 8Neha SharmaNo ratings yet

- Vda. de Manalo vs. Court of AppealsDocument13 pagesVda. de Manalo vs. Court of AppealsDianne May CruzNo ratings yet

- Article - Application of Liquidated DamagesDocument14 pagesArticle - Application of Liquidated DamagesYayank AteulNo ratings yet

- Topic 2-Proceedings in Company Liquidation - PPTX LatestDocument72 pagesTopic 2-Proceedings in Company Liquidation - PPTX Latestredz00No ratings yet

- Obli Con SemifinalsDocument32 pagesObli Con SemifinalsMingNo ratings yet

- SSGT. Pacoy Vs Hon. CajigalDocument9 pagesSSGT. Pacoy Vs Hon. CajigalJakie CruzNo ratings yet

- Sudhir Agarwal 12Document251 pagesSudhir Agarwal 12kayalonthewebNo ratings yet

- Cagungun vs. Planters Dev't BankDocument21 pagesCagungun vs. Planters Dev't BankBam BathanNo ratings yet

- Immigration Case Reverses Injunction for Chinese FamilyDocument7 pagesImmigration Case Reverses Injunction for Chinese FamilyErwin BernardinoNo ratings yet

- Au Meng Nam & Anor V Ung Yak Chew & Ors2007Document62 pagesAu Meng Nam & Anor V Ung Yak Chew & Ors2007Muhammad NajmiNo ratings yet

![[G.R. No. L-10128. November 13, 1956.] MAMERTO C. CORRE, Plaintiff-Appellant, vs. GUADALUPE TAN CORRE, Defendant-Appellee. _ NOVEMBER 1956 - PHILIPPINE SUPREME COURT JURISPRUDENCE - CHANROBLES VIRTUAL LAW LIBRARY](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/452807200/149x198/f8f1120e84/1710591200?v=1)