Professional Documents

Culture Documents

English Grammar For Today, G.leech - M.deucar - R.hogenraad, MacMillan

Uploaded by

Anca Mariana0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views121 pagesgrammar book Leech

Original Title

English Grammar for Today, G.leech - M.deucar - R.hogenraad, MacMillan

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentgrammar book Leech

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views121 pagesEnglish Grammar For Today, G.leech - M.deucar - R.hogenraad, MacMillan

Uploaded by

Anca Marianagrammar book Leech

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 121

4

English Grammar for Today

‘A new introduction

Geoffrey Leech

Margaret Deuchar

Robert Hoogenraad

MACMILLAN

cmon in

© Gootrey Lote, Margret Deucher, Robert Hoogearia 982

Allright reserved No eprouton, copy or tansmison of

‘hs pbs maybe made wit weten permission,

No pararaph ofthis puiearon maybe reproaced, cope or

‘suited ve with writen prin on accordnce wi

the poinnn Ue Coppa Dei so Pos Act 508,

‘rater the tame oan once pernstng aed copying

{Suey he Copia Liens Agony, 9 Totem Cou

Rosa Loudon WIP SHE.

Ay person wh dos ay wuts act in elation his

ueton ay einen exis rsecaton ad

ie for damage.

int publi 1982 by

‘THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD

Hovngrl, Bsinguoke, Hampshire RGD 2XS

td Landon

‘Compania eresenstves

throwghow he wer

ISBN 0-333-3054-0harcover

ISBNO-335 506409 paperback

Printed in Hong Kong

pene 1982 (wth caren), 1984 with eiso),

955 (ic), 1986 987 98,1980, 1981, 1983,

Contents

Foreword

Preface

Symbols and conventions

(o ean a: TRODUCTION

1 What grammar sand isnot

‘Grammar apd ole in language

“Good” ant ‘bad? grammar

Variation in language

[English and other languages

Grammar and effective communication

‘Grammar in prose style

(Grammar in poetry

Conlon

Everciet

PART B: ANALYSS

'D Sentences and thei parts

21 Prologue: pris of spech

22 Thehierschy of units

23° Grammatial notations

24 Uaing teats

255 Form and fonction

25 Summary

Beeries

3 Words

31 Open and closed word cases

32 The open dases

34 Sommary and conshsion

Beerciaes

30

2

36

37

ry

56

ss

2

B

4

contexts

Phrases

41 Clans of pha

42 Mainand ubardaate phases

43° Noun phases and related phrase clases

‘44 The adjective phase and the deb pase

45° The ver phrwe

46 Sommay

Beeres

tense

Sil Elements of the cause

52 Complex sentence

53 Finite and nonfnte clauses

54 Declarative interogatie and imperative

clause

SS Actie and passive aus

S16 Move on clause structure

57 Cause paters

58 The structure of non-finite causes

59 Parsing simple sentence

5.10. Summary

Beeries

‘Subordination and coordination

61 Subordinate causes

62 Fite subordinate causes

63. Tae functions of subordinate causes

64 Nonfinitesubordinas causes

65 Direceand lndivest sbordiation

66 Skeleton analyse

67 Coordination

63 Summary and conclusion

Exerc:

asic and derived structures

Ta Constventstrectare grammar

72 Badeand derived strotures

73 Mising’ elements

74 Sot eonstiuents

73 ‘Double analysis"

715 Back to parsing

7

58

0

85

7

n

1%

n

*

»

2

2

84

86

"7

3

31

93

100

01

105

1s

107

109

mL

Eo

93

113

13

us

us

119

120

123

17

78

contents

Style and transformations

‘Summary and coneusion

Beercaes

% pant c: aeucarions

|

| :

|

Tnodctory

Speech and wating: which comes ist?

unclons of wating and sesh

‘The form of speech and wring

Linguistic harcterstics of speech and

wating

‘Azalyss of spoken and written diesouree

Cencusion

Tnsrodustory

‘Tenor

‘Teno and discourse

Domain

Domain and dicoure

Combining categories of use

Exerebe

Analysis of literary discourse

101

102

103

104

How toamiyse syle

lutrative extract

Outine analysis

Further iustatve extracts for dacuson

Bxerises

Grammar and problons of wage

‘Opinions about grammar

Prescriptive "les

‘The pests of wage

The problem of personal pronouns

The problem of number concord

‘The problem ofthe goer matcline

Probleme of lips

2s

128

ne

145

us

us

146

150

151

153

uss

158

se

166

1st

168

110

m

m

im

114

us

vi

Bn

contexts

11.8 Dangling on-fnte claves

119 Condusion

Exeries

Grammar and composition

re

122

03

08

n3

126

Answer to exercises

Fur

Index

er realire

180

181

182

186

184

190

191

we

193

ws

199

2s

28

184

Foreword

‘Voisin the Baglsh Asoiation ave been urpng for some tine tat

‘he moment ip for anew English gramsar fr usin schools colleges

nd univers and the Amoiation hasbeen fortunate in bringing to

(ber tee authors whowe distinction and experi eminently qualify

‘em fr the task and' pubsher long established inthe Se.

Tt i probably true to my that not many years ago sucha book could

aly ave attracted a publisher, fortwo very good resons,

“The clmate of opinion has for long been unftvoursbi to ving

rammatial teaching to nati speakers of English. From cases that

Sle need not go into ere, the old tradition of school grammar wane.

“Grammnas foc Toei Ierers was acknowedged to be unavoidable the

eet us could manage without. And 4, of course, many of us aid;

Sd perhaps we fet the language survived qltehappily when we dd not

{Ook too Cony, whether 4 teachers cea students ofa nea users

fof the language, 3 he imprecision, the incoherence and - let us const

often the incompreenablity of much of what we read or even

‘wrote in oar everyday Ines,

SA ceond reason Wat severly practical ti after al, ot ong since

Profesor Randolph Quirk complained of the absence of any yound

{sterion by which to establish what really was acceptable English: the

Srter ofa feching grammar iat the grammatical lewel lost

Tatiely without « body of descriptive data, and so he has to rely

{angel on a hesitant and nertain introspection ino his own wsage o

is intuve knowedge

"That the situation has changed is due in great measure to Professor

{Quik and his collages inthe Surey of English Usage, at University

College, London, and to its daughter project at the University of

Tancancr, where Profesor Leech and is colleagues are investigating

* Rando Ql, comsen na tee rp in i ss on a ei

[gue Med and Moore (Lomion Longman 1968110

x FOREWORD

present-day English withthe si ofthe computer. By far the most im

povtant achievement of thi new emphasis on the study of Engh

[arma through ft usage in the Isngusge Ie surely the monumental

‘Grammar of Contemporary Engiah which is widely regaded as

sutbortauve.

“Authorttiw’, Uke the word ‘authority’ ie kely to sais hackles,

snd 4 te prope to point ou that it authoritative statements of the

‘ts of English today that aren question, not rulesastohow weshould|

‘or should not expos oureles Re there wilbe, based on unqueston-

thle fat, but often It sa mater rather of grades of acceptability. We

Tateve ther is now a growing body of option eager for direction of|

‘hirkind,

WWehope that Bln Gramma for Today willsere a vatsbl ool

for students, however litle thlr Koowlodge of eemmaticl terms, a

alo for teacher, whether Inclined more toa traditional or « modem

fpproach, who belive thats rstumn to 2 viglant and welinformed

tad towards the language they use and lve slong overdue

"The English Assocation Is grateful to the authors for the care they

‘nave gen to the prepartion ofthis book, and to thos ofits members

snd offs Executive Comittee who red earier drafts and contated

suggestion for improvement. Further sugestios from readers wil be

‘wolomed.

GEOFFREY HARLOW

(Chairman, Publications Subcommittee,

The English Assocation,

1 Priory Gandess, Bedford Pak,

Tendon, W4 ITT

* by Rai Gu ey Gnomes ah etx Sati

(Goosen: Lona, 17

Preface

“his is an lataductory outs in English gramma for use in Engish-

‘madi schools, coleges aa universities, Lamentably, theresa present

to recognised ple for Engluh grammar in the Brith educational

Cuca, En fact 8 ll possible fora student to end up witha degre

in Engl ate Brishunivesity without having case to know tho fst

thing about English grammar, or the grammar of any other language

Buti we ace rights supposing that the time sight fora real of

the subject in schools, tte wil be » rowing acd fr introductory

‘Soursey at various level, Thu thie bok as a multiple parpos. I

‘rimily designed as coursebook fr salents atthe upper secondary

‘Boe (oc forms) and the tetary level oles, polytechnics, ulver-

Stes), but it is also adapted to the needs of teacher intersted inex

loving ¢ new approach fo grammr, or of any person keen fo catch UP

‘th subject 50 wetchedly neglected by our education system.

If grammar is to besome tal subject inthe English eusicaum, we

tye fo enor finally the spectre of Browring’s grammarian who

Gave us the doctrine of the enclite De

‘Dead from the wast down,

‘Rober Browning, The Gramimarions Funerl)

‘That spectre sll aunts our colectve consciousness inthe form ofa

Viciorun schoolmaster instilling gulty felings about split infntivs|

And dangling prtepee, and vague Tears that grammar may prove tobe

fothing els tha hacking the corpses of sentences to pieces and stick

ing labels onthe resting fragments. That is why’ some ofthis book i

evoted to the correcting of preconceptions. Part A Intoduction is

meant to provide «reorientation: dspeling myths, and seeking 2 new

{Appa f the veoe uc yanmar i peewneday eduction. Pert B.

“Anaya is the man ar ofthe book, presenting a method *

{ng the grammatial structure of sentenoes, Pat C, “Applicat

x FOREWORD

roent-day Enlish with the ald of the computes. By far the most i

fortant achievement of this new emphass on tho study of English

fzammar though is sage inthe language surely the monumental

Grammar of Contemporary Engish, which is widely regarded a

suthorte.

“Authortie’, Uke the word ‘authority, likely to raise hackles,

‘and so ts prope to point ou that it authoritative statements of the

faetoF English today that are in question, not rulesasto how we should

‘or should aot expos ourselves. Rules there willbe, based on unguston

thle fat, but often it isa mater rather of pades of acceptability. We

belive there is now 2 growing body of opinion eager for direetion of

this kind,

‘We hope that English Grammar for Today wilsere as valsble ool

for students, however lite thelr Knowledge of grammatical tems, and

also Tex aches, whether nclaed more to a tadltionl or a modem

Spproach, who Talive that a rtura to a viglant and wellinformed

tude towards the language they use and love i long overdue.

‘The English Association Is grateful tothe authors for the care they

‘havo given to th preparation of this ok, ani to thos ofits members

sd of its Executive Commitee who red ear rafts and contted

Suggestions for improvement. Further suggestions from readers wil be

swolomed

GrorFREY HARLOW

Chairman, Publcations Subcommittee,

‘The English Assocation,

1 Priory Gardens, Beford Park,

indon, W4 ITT

1 by Randolph Qu, siney Geetuun, Guotoy Leech and Jan Snrteik

(onion: Longa, 1972),

Preface

‘This isan Intodetory course in English grammar for ase in English

‘medium schools, colleges and universities. Lamentably, thereat present

‘0 recogaised place for English grammar in the Buitsh educational

uric, fn fact i stil possible for astuent tend up witha degree

in Englah at Beith university without having cause to know the fist

thing about Engish grnumar, or the grammar of any other langue

[Buti we are ight fm supposing that the ime is ight foc a real of|

the subject in tahool, tate wil be a rowing need for introductory

‘courses at various levels. Thus this book ha a multiple purpose, Ii

‘Primal dened st couse book for stents atthe upper secondary

{evel (ech form) andthe teary level colleges, polytechnic, univer

sites), but iti abo adapted tothe needs of teachers interested inex

ploring «new approach to gram, or of say person Kees to catch up

‘with eobjec 40 wetchely neglected by our educational syste

if grammar isto become a ital subject in the English curiculsm, we

tye fo exocce finally the specte of Brownings grammarian who

‘Gave us the doctrine f the ence De

‘Dead irom the wait down,

(ober Browning, The Grammartan’s Funeral)

‘That spectre stl aunts our collective consciousness inthe form ofa

‘Victorian schoolmaster inating guy feelings about split infntves

Ain dangling participles, and ygve fers that grammar may prove tobe

nothing else than hacking the corpse of satences to pieces and stick

ing ibels onthe vesting fragments. That s why some ofthis book i

‘devoted tothe correcting of preconceptions. Pat A, “ntoducton is

tneant to provide a reorientation: dapeling anys, and seeking 2 new

fppmisil GF the vue of grammar tm presutay education. Pat Dy

‘Analysis the main prt ofthe book, presen ¢ method fr dese

ing the grammutial structure of entenoes. Past C,“Applations shows

xi PREFACE

how this method of analysis can be used in the study of style i its

broadest sense and inthe development of writen language ls.

‘The ystm of grammatical analysis introduced in Part Bisinluenced

by the semle grammar of McA. Halliday, and more directly by

that found ia Randolph Quis etal, A Grammar of Contemporary

English (1972) ands adaptations ia Quik and Greenbaum, A Unvesty

(Granonar of Englth (1974) and Leech and Svar, A Communicabe

Grammar of Engl (1975). 1s feamowork which hasbeen widely

‘opted inthe tudy of Eglh by notaative speakers, making informal

‘we of moder developments in lnguiss, but not departing without

{good reason from tadiona terme snd eitegories which aze to some

{xtent a coramon cultural hetage of the Western world. Naturally the

Framework has had to be considerably simplified. Grammar, for our

purpot, is defined In a ntrow sense for which nowadays the tem

‘Symax is someties usd. It means roughly “the rules for constructing

sentences out of words and it excludes, tcl speaking, the study of

‘what words and sntencs mean and how the ae pronounced.

‘Exerees ave provided atthe en ofeach chapter, bat ther funtion

fn each Pact somewhat diferent. For Par A the execs ae merely

fn encourgement towards thinking on new ins about grammar. Ia

Part B the exerces are mush mote fully integrated into the leaning

process, important for students to et thelr progres ia understand-

tng the sjeem hy doing the exercnes where diated, In part C the

exercises in Chapters 8-10 invite the student to try out the system of

(wammatial analysis on diferent styles and varieties of English. Here

[ram wil be seen in relation to other levels of langue, euch

‘eaning and vocabulary, as pat ofthe total funcdoning of language a

‘ communiation system,

"The book can be ued a a course book, each chapter providing one

cor two weeks work, though the exercises are varied in form and pur

pote, Some exercises const of problems with more or less defite

Snswers and in those cass answers are gen atthe back ofthe book

(p.199-214), Oiherexereies are openended tasks fo which no answers

tt be piven, The exercles which have anowers provided are so ndicted

by the rosvzeference ‘answers on. 00 alone the heading. Thus

Mae using the Book for peat sty wil ain some feedback, while

‘eachers using the book ata course book wil fad enough material for

‘woek-by-veek preparation and discusdon, in addon to the exercises

‘which students may check for themselves.

Following the Answers to Exucss, we lit books and aris for

Further Reaing (on pp 215-17). The ist alphabetical, andon the fe

‘ccaion in the text where we need to refer to one ofthe works sted,

references ae given by the author's name, the tie, and the date of

PREFACE ai

publication: og “Crystal Lint, 1971" It would be imposible to

[ive due ered to grammars and ther scholars whose work and ideas

[ve influenced this book deel or iniecly; where such Meas have

‘Become part of the curtency of present-day linguistic, we make no

attempt fo do.

“though the book does aot Include a losary of technical terms,

the function of sich a losury can be matched by careful use of the

Index, in which technical terms of grammar ae listed alphabetically,

‘ogetier wit the pages on which they are introduced and explained.

"We tank Martin MeDonald for providing us wth the material quoted

on pp 131, 193, 135-5

‘We owe a general debt 10 the English Association, which provided

the impetus and opportunity for the writing of this book, and.» more

patiolr debt {0 the Chatman of it Publetons Subcommittee,

Geofivey Harlow, and to other members of the Asocation, especialy

Raymond Chapman, who have piven us encouragement and detaled

uldance

Lancaster CCEOFFREY LEECH

August 1981 MARGARET DELHAR

ROBERT HOOGENRAAD

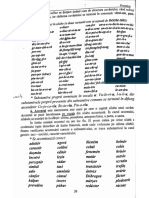

Symbols and conventions

‘The szetons whore the symbol or convention is fist intoduoed, and

where the grammaticsl category i most fully discussed, are here shown

in backs

Labels

Function label

An Advetblal(253;5.13) My Main verb (25.3348)

Aue “Ausliny web G53; 0 Objct @25.2;5.1.2)

43) 04 Dizet abject 5.5).

© Complement 253:5.12) OF Indirect object (5.6)

Object complement (55) Prediestor(25.2:8.1.1)

CE Subjecccomplement——S_—_Subject (2$3;5.L1)

(23:56) Voc Voeutve 6.)

Ho Head 25334.)

‘M_—(Pre-or post) modifier

5341)

Form labels

ACI" Adverbia cluee (6.1.1; NCL Noun dause(611;62.1)

622) NP Noun phnse 2.5.1:

Aj Adjective @5.1;323) 43)

AP Adjective phate @-S.1; yp Proposition (2.5333.34)

4a) Por Prepostional cause (62.5)

Ay Adwib @5.;324) Ph Fhutse(22)

ANP Adve phge(25.1; pn Pronoun (3.13332;

G42) 43.2)

(CCL Comparative cause PP Prepostional phrase

(624) @5:;433)

svata01s aND CONVENTIONS w

sbordinaingoreo- == N_ Noun (25.1;321)

‘ordiatng) con RCI Relative dase (62.3)

junction(31;335) ~ Genitive muzer (4;

.hause(22) for Ci, ‘434

‘Cling. Clen,see below) SCI_Sbortnate clause (5.26.1)

4 Detemniner(3.1:33.1; Se Sentence (2.2),

432) Vi Verb (25.1;322) (sed

Enumerator (3.13333) for fuller or operator.

GP Gentine phrase 05.5, wet)

434), ¥ Opecatorib (.1;33.)

4 mtenecton (3.1533. VP Vers pra 25.1583)

‘MCL Mais dause (52) Wo Word (22)

Composite labels

1, ACI, CCI, NCL and RCI combine with ng, en to form composite

‘abel for nonin dus pes

ch tate de

Gi hodiae "| GayrAce Neher 6a)

Gon “tn ceo

‘Vand combine with o, 5, ed 1 ing, en to form compost label for

finite and non ft vec forms:

Vo Prewnt tons or base form

Ve Third person singular present tense form } (3.2.2,3.36,45.1)

Ved Psst tense form

Vi Ininsuve (451)

Ving “ING or preset participle

Yor “Recreate ¥ 2a,a3.483)

Specialised ies

‘The folowing symbols are used, mainly in 4.5, for sbelases of Aue

and

Aus:Mod Modality (45) vibe Primary eb t0be(3.3.6

Past Pasive voice (45) 35)

Por Pecective aspect do Dummy? ved do (45;

G3) 452)

Propewive pet hv rimary vee 4 Ave

a3) G35)43)

mm Modal mb (.3.6;45)

wi SYMBOLS AND CONVENTIONS.

“The following particles (3.3.8) are used as their own abel:

it ‘empty’ subject there ‘existent there (7.72)

oa) for infinitive marker (34)

rot saute negation (4)

{i soxnd clauses

©) round phases ean)

fepraten word constituents

‘hele wo ox more coordinates (6.7)

fnclore an optional constituent (2.4.4)

links interrupted constituents of sunt (5.13): 0g (he) kit

nay

[

Labeing

‘The aymbol* (ote) rede an ungrmmatel consicton 25.1.

Fon nbls 21) havea ital ail for open cases, lower cat

Tor coved le, Tey ace weten as uss before te opening

trackt oc before the word: xe(yaYou).

Function abe 3.2) arin ain the text whe weting them se

raring: cae 8 for S- They are won ar oper before

the opening bast or ttre the word: (You!

nation pis form ily 21,338) the function els witen

hove te form abet es ou,

Skeleton analysis 6)

rea direlly subordinated constituent (6.5.1, 66)

shore tn indie subordinated constituent (6.5.2, 6.6)

“The aymbo + (pls) stands forthe coordinating conjunction inked

hordnation (67)

‘The comma is usd between coordinates in unlinked coordination

Yer)

‘Tree dlagrams (232)

S205 9.9m how to bull up uly labelled toe agra,

PART A

INTRODUCTION

1

What grammar is and is not

1.1. Grammar and its role in language

[es important fom the ouset that we are dear about what we mean

by the teem GRAMMAR inthis boo. Many people think of prammar as

Yatherborig schol subject which has tle use in elif. They may

Ihave come acoss the concept in Latin 0" lee, in Eaglsh composition,

for ln the explanations of teacher as whit poo! or "ba grammar

So grammar soften asocatedin people's minds with one ofthe follow-

sgammar is completely wrong, but they do not represent the whole

plete

In tis book we shall se the term grammar inrternce tothe mach

anism according to which anguage works when tis sed to communicate

‘with other people. We cannot se ths mechanism eoneretely, becuse it

[i represented rather abstractly inthe human mind, but we know i is

‘thae because it works. One way of dessin this mechanism sas a set

‘fale wilh allow us to pot words together in certain ay, Dut wich

do not allow others. At some level, speakers ofa language must know

‘those rae, ocherwis they would not be able to put words togeter ins

meaningful wy.

‘Even they have never ard ofthe word grammaralnatve speakers

‘of English (le. thowe who have learned Engl ar tel ist langasee)

know at least unconscious that adjectives are placed before nouns in

English. Thos you would get unanimous agreement among Englsh

spurs tat The bie ook ison the ble where Dhe wa adjective,

Book s noun) Isa possible sentence, wheteas The Book ble it om the

table i not.

if we stidy the grammar of our native language, then we ae tying

‘to make expt the mnowiedge o he inguage tat wealreasy hae, We

might do this out of pure curiosity a to how Inguage works, but we

‘ight alo find the knowlege wef fr other purposes, We might wish

3

4 [ENGLISH[GRAMMAR FOR TODAY

to teach Engl to frelgnee, or example, of wouk out how a foreign

lnnguaps i diferent from our ov. Or we might want 19 work out how

the language of poetry or advertang makes an ingact onus, lean (0

‘tice and improve our own style of writing.

‘So fr weve eid crely that gamma isa mechanism fr puting

‘words together, but we fave si ite sbout sound or meaning. We can

Think of paar a Being conta prt of language which lates sound

find meaning. The meaning of a message conveyed by language has tobe

fonverted into words put tether scording f grammatical rls, nd

these word are then conveyed by sound. The term PHONOLOGY iscften|

neg to mean the sytem of sounds in language, and seMATIC, the

‘ystems of meaning, However, in thisbook we willbe concerned mainly

‘wih. the central component of language, GRAMMAR, which relates

[Phonology and semantic, or sound and meaning. The ilationstip be

{ween the thre components in epresered in Flgue

Figure 1.1

‘Semantics ‘Grammar Phonology

‘So meanings are conveyed, va grammar, in sounds but what about

ting? One of the eas which many people have about languages that

{thas odo withthe watten langage. The word grammar in fact comes

from the Grek grapho, meaning wre’, Du although statements

the origin of words such at th may be interesting soil, we ean-

‘ot rely on them o tll us the cunent meaning ofthe words reanings

Change inte, Tadionaly, grammar di have todo with tho watt

tanguge, especially that of Latin, which continuo be stuled and

‘ued ins wtten form log ae It had cand tobe generally spoken.

But the waten form of nguage really only secondary toitsspoken

form, which developed fist. Chkren ean to speak before they lea

fo wie, and whereas they letn to speak naturally, witout tition,

from the lnguae they hear around them, they have fo be teu 16

Arte: Ht iyo covert hic speech tox written or secondary Form.

Tower, waking performs an extremely important function in out

fallure Gee Chptr 8) an inthis book we Bll Wey gemma ab

Inechansm for producing both speck and writing. Therefore we can

‘modify our revots diagram as shown in Figure 1.2.

WHAT GRAMOUAR 1S AND IS NOT. 5

Figue 1.2

Phonobay

‘Semantics ra ng tems

1.2. ‘Good’ and ‘bad? grammar

"The terms good and bad do not apoy to grammar inthe way in which

‘We ate using that term in this book. If we Wew grammar asset of rales

‘whic deserve how we use language, the als themselves are pot good

‘rad, though they may be described adequately or inadequately ins

‘eserition of how the language Works.

Linguists who write grammars are concerned with desribing how

‘the language ls ed rather than preserbing how i shouldbe used. So if

itis common for people to Use sontenoes sich as Who di you give this,

fo? hen te rls of a desrptiv gaammar must allow for this type of

Senience nits ues, Thos concerned with prescription, however, might

onder this to bean example of bad grammar’ and might sgest that

‘To whom did you gve this would be a better sentence. What is con-

‘dered better ot wort, however fofno concer toa descriptive ngs,

fn writing a prommar that acsounts for the way people sctaly se

language. If people re communicating efectively with language, then

they tmst be following rales, even if those rules are not univesally

tpproved. The role of the linguist i thus analogous to that ofthe

{nthropoigit who, if asked to desc a yateuar culture's eting

Tubts, would be expected to doso without exposing personal opinion

fs to what they should be like, The later would be prescriptive ap-

‘roach. lee probably easier, howewer, o avo being prescriptive when

eating with cultare other than our ow. Ax spears of oar native

language we are bound to have feat or proscriptve notions about how,

it soul! be usd. But we should beable to separate the expression of

‘our own opinions fom the activity of describing actual langue se

‘though the foo ofthis book i tobe on descriptive amma, we

have to recognise the existence ofpreseriptve rls, uch a that which

Says that one sould qoid ending sentence witha preposition. This

"Tle wat broken in the example quoted abowe (Who did you gv his

tot) because the pepoation #0 & place atthe end of the sentence,

reserpine rues are leary not grammatical ues i the sme sense as

Ascrpuive roles, so might be eppropriste to cll thr rules of gram-

faved! eiquetes Then ove cau > Ul whut some people cll bad

‘rama fe akin to ad mannecs Le refers to something you might

Iwan to avoid doing, onl to convey a good impreson ins particular

6 ENGLISH GRAMMAR FOR TODAY

situation, Some people consider it bad manners to put one's eows on|

the table wil eating and yet, fom a descriptive olnt of ew, oscars

father often, Nevertheless, people who eat regularly at home with their

‘cows on the table might avoid doing it ata formal diner party, simply

‘cae t would not be appropriate behaviour in sucha wetting Sil

there are oceasions when being on on

theying ules whit one would nat normally obey

“Fis ead us tothe point that, as woll a knowing the grammatical

rules of language, Is speakers aso have to Know how to we the

language appropriately, and this often Involves a choice between dif

ferent opto oe diffrent LANGUAGE VARIETIES.

1.3. Variation in anguage

131 Introduction

Ii-we were to take + dopmtily prescriptive approach to langue, we

‘nigh suger that tere was Just one, ‘omee™ form ofthe langage

‘which everyone should we, We might reognise that not everyone speaks

the correct form of thelnguaz, but we would describe any ther orm

simply wrong

however, We are to take the descriptive approach explored in ths

book, we eaanotdimiss some forms of language a incorrect: we have

tobe prepaed to desrbe all ites of language.

‘A deseitve approach fecognises that there are many varieties of @

language auch ae English. We can eatily Americans as speaking ina

“ferent way ftom Bitsh people, northerners fom southerners, Young

ftom ol, middle cass people rom workinglas peopl, and men from

twomen, So language wl vary according to crn characteristics of ts

‘USER. A wie’ speoch may well elect several ofthese characteristics

simulianeously for example, young woman may wellspea diferent

fiom botha young man and an oder Woman

‘So language cin vary fom user to user, depending onthe users

‘pecsonal characteristic, This 90 meant fo imply that each peron

{peaks a uniform variety of languape which never changes, OF course

‘poech may change a personal characteristics change: as young person

‘Becomes olde, a northerner moves south, or socalcas: membership

tGhnges asa result of edueaton, for example. In adition, «person's

Speech wll ary according to th USE. at speechisput to. or example,

the way you tact a filend wil be diferent from the way you alk 0

[Snoaager The wey you tall om the telephone wl be diferent om thn

tray you tlk to somoone face to face, and you wil we yet anther

‘avy in wing alter. Your language wil als vary acording to what

|WHATGRANBEAR If AND IS NOT 1

you are talking about, e. spor, pots or religion. The variation of

Tinpuage eesoring to ite woe menns hat each wor has a Whole range of

Tunguage varies which e or ah leans by experience, nd knows how

to wse appropriately If you talked in the castoom as you would in the

pub, you might be considered ilmannered (dis might be using "bad

[zammar fom a preciptive point of vew),and if you addressed your

fend as you would your teacher, you might be laughed

Ws ow omer tion tng cord rand wt a

sore deal

132 Variation according to wee

Gharacteritin of the anguage ver which can effect language include

the following! reponal oii, social class membership, age and sex. A

‘ful term fn connection with thew characteristics is DIALECT, This it

‘often ded to deserve rial ogi, asin, for example, Yorkshire

‘alot, Cockney (London) dislect, But canbe wsed to refer to any

language vrety related tothe personal characteristics sted above.

‘REGIONAL ORIGIN, We ean often tll where a person coma rom by

the way he or she speaks. Depending on how far we are withthe

aety of a ven region, we may be able to identi, fr example,

(Cockney, Yorkshire, Soous (Liverpool) or Geordie (Tyneside) speech,

‘We ean Hentfy speech on the bass of ts pronunciation, voabulry or

grammar, For example, in Yorkshire daect, asin some other northern

{Edtet he words pu and pur are pronounced slice becaute the vowel

found inthe standard or southern pronuclation of words sich as ust,

‘hs, eup ete snot wed. The dict also has its own voeabulary, for

trample, the use of che word happen to mean ‘perhaps Fnally,on the

level of pramumar, Yorkshire dialect has were asthe ast tense ofthe

‘er De nalts forme, 30 that, for example, he were ishearé commonly

Insead of he war, So dnc cn be eatifiod on the lees of promunc-

ston, vocsbulary and rama. Voesbuliry end grammar are the mos

base levee for describing dialect, since regional pronunciation, or

‘gional ACCENT, can be Used When Speaking standard English swell as

when speaking a epional lect

"A this plat i should be emphaabed that the term dilect does not

imply an ioorect or deviant eof language: itis imply used to mean

‘valet of language determined by the characteris of usr Some

tines, however the term may be ued to refer to vareisof the guage

‘which are not STANDARD. The standard language isin fact just another

‘arity or dalect, but ia Beltain i happens to be established os that

‘ety which generally wed by southern Beith, educated speakers

‘F the Langage, and in writing aod in ple usage suchas on radio and

“elevision. Ir sometines known as BBC Empl or even ‘The Quen

8 ENGLISH GRAMMAR FOR TODAY

English. Standard Engh ot inherently beter or snre‘pamaaticl?

than non-standard English (all varieties ave grammatical in that they

{follow ules, but it has prestige for soci athr than linguistic eatons.

Its prestige i due tothe fat that it is ultimately based on the speech

of educated peopl living inthe southeast of England, whee the in

Dortant institutions of goverment and eduction became exsbliha.

‘Because standaré English sth best-Known variety of Engin Brita,

‘we chal ust for analy in Part B of thls book,

SOCAL-CLASS MEMSERSHD. The extent {0 which we can identify

socials dialects is controversial but te socal clas ofthe speaker

foes seem to affect the variety ofthe anguape aod. In Brita there

‘an interesting relationship between socal slat and the we of tanard

‘and nonstandard spech in Ut the “higher” you are up the socal sae,

the les lksly you ae to use nonatandand or regionally Aentifable

‘speech, This means that itis not usualy poasble to iSentify the eponal

Dackgiound of, for example, an uppe-micdle-cas peaker educated at

public schol. Tomake tls clearer, imagine that you tel rom Land's

Ed to John O'Groats talking only io Factory workers and taperecoré-

ing thei speech. Then, on th way back, you take tho same out, but

‘ecord only the speech of ‘profesional suchas doctors and teaches

(On comparing the tapezecordngs you Would expect to find more

‘atiaton nthe speech of the workers that in tha ofthe profesionals

‘The speech of workers would contain higher proportion of features

which ae not found in the standard lnguage, Several of these features

‘would be found in more than one aeafor example, done asthe past

tense of dois found in both Liverpool and London among werking-as

‘speakers (who might say, for example, done as opposed tod i).

"AGE. Lis is Known about tho effect of age on lanevage vation,

‘but there may be grammatical features which disingish ae dialect 0

some exten. For example, the question Do ye hive some money?

‘would be more likely tobe take by a younger speaker of Bish English

(tis common for speakers of all ages in American English) thananolder

speaker, a the latter would be more lel to say Have you (01 some

‘money? The way young people speak eof pate interes nay

‘be indcative ofthe dieetion in which she language i changing.

SEX, Thete seem to be some ingusti dferencesscoording to the

speakers sx, though litle i yet known about them, However ceria

‘rammatialfntures have been tzoclted more with wormen han with

‘nen, and it hasbeen found that women are more ely to use standard

than men,

Tt should by now be cer tat perl character of te language

user can combine to affect the varetyof guage wd. The termcilet

fas been vse for convenience to Scent the effete ofthese caacts-

[WHAT ORAMOAR IS AND IS NOT 9

Inte, ati, for example, reponal det, socials der, ut thee

‘remot ray seprato ones. All he characters ntrat with one

Soother, 20 that any individual wl speak a Tanguge vase) made up of

features fom several lect,

133 Variation according to te

{As was point out in 131, 00 user of language uses one uniform

‘arity of language. Language also varies acording othe se fo which

Ite put, Wh he term ditc x convenient to refer to langue Yari-

tion according tothe user, REGISTER canbe used 0 refer to vation

{scordng to uke Gomer ao known as ‘tle’) Regier can be

Suhdiided ino thee categories of language use, each of which affects

the language vast. These ate: TENOR, MODE and DOMAWY

"TENOR: This has todo with the relationship Between a speaker and

the addesee(s) ina pres situation, and soften characterise by seater

‘or lesser formal. For example, «request to close the window might

be Would you be so Kind as fo cbse he window? ina forma situation,

compared with Shut the window, pews in an informal situation,

Formality alo his the effect of producing speech which Is dose tothe

‘andard, For example, a witnesin court might be cael to say He

‘dn’ do, Your Honour, rather than neser done which might be

‘aid to Cockney speaking fends outa the courtroom. A speak has

{okaow which sthe ght kind of nguage tows in which drcumetances,

‘ough sometimes the wrong choice may be made debberately, for

humors or sarcastic effec.

MODE. This ha o do with te effets ofthe melium in which the

language is transite. Spoken language used in faetoface situations

rakes use of many ‘nonsebal movements sich ay gestures and Tall

‘xpreeonsOnthe telephone, however, the sul chanel isnot rahe

50 that, fr example, Yes has to be substituted for headnodding. In

‘writing only the vil chanel is avalbleso that theofTet of ntonaton,

‘or tone of vic cannot be conveyed, except, in pat by graphic means

such as exclnation- and questionsmarks. Witte language usually in-

Wolves the additonal curated thatthe adreee, who 0 present,

Cannot respond immediatly and this has an effect onthe language For

‘example, in letrs, dict questions tendo be less common than in

onverstion, 2 that you might be more ely to write, for example,

‘Let me know vhether you are coming than Are you coming? Ths

category of mode is particularly relrant forthe distinction between

‘writen and spokea language, and tis wil be iven further consideration

in chapter.

DOMAIN. This has to do with how language vases aconding to the

‘actty la which plays part. seminar about chemistry, for example,

0 ENGLISH GRAMMAR FOR TODAY

wll invole a witer range of vocabulary, more technical terms and

possibly longer entences than a convertion about the weather (ones

by meteoroloits!). Siilry, the language of pal document wl be

ferent fom that of an advertisement, and the language ofa rious

Service wil be diferent from tht of newspaper eporting. We can ths

{efer tothe domaine of chemistry law, religion, and soo

‘As with dnet variation, the categories of register variation ll affect

lunguage simultaneously so that we cannot really identify dsrete

reuters any more than discrete dialects Also, dialect and repister

“arltion interac with exch other since both the dimensions of weer and

‘Ge are aways prevent

“To summarise what has been sid in this selon (13), language varies

scoring to both wer and use. Cetaln pesonal characteristics wl be

reflected in te speech of given petion and that person wil als have

sts o a range of varieties appropriate for various ws

1.4 English and other languages

144 What isa language?

‘So far we have shown that a langage such as English has many diferent

‘arses, which reult from a combination of factors. We have aso

Shown that these varies ae aot separate entices, and tht although

they ean be descubed onthe bas of linguistic Features they cannot be

categorically dstinguisod from one another.

‘We have act questioned the assumption, however, that a language

snade up of such varieties can be clea distinguished from all other

[nnguage. Is true that we have separate labels for diferent languages,

eg. Engh, French, Chinese, but the exstnce of labels should not

Asie us ino believing that these are linguistically welldefined entities,

(One ererion used to define a langage is MUTUAL INTELLIGIBILITY. AC

coring to this, people who can understand each other speak the same

language, whereas those who cannot do not. But thee are degrees of

‘comprehension, For example, southern Brith English speakers may

ave difficulty understanding Geordlo, end American Engish speakers

‘may fad It vitally incomprehensible” Thee even les rutul itl

bility In the roup of “dlects refered to os Chinese: speakers of

Mandarin, for example, cannot understand Cantonese, though both use

‘the same writen language. On the other hand, n Sendinai, speakers

of Norwegian, Dansh nd Swedsh can often understand one another,

‘ven though they speak what are called diferent lnguage. Scandinavia

‘were one political entity, then these languages might Be considered

WHAT GRAMOKAR IS AND 1S NOT "

lect of just one language. So the cxtesa for defining languages are

ten politi and geographical rahor than tcl igus

1.42, Grammatieal rls in English and other

Tee iangunge vary reed aba standard langage rather than

dialect (sally fornomtingiste reasons), then it as more soci prestige.

“This explain, for example, the nstenceof separatists in Catalonia that

Catalan i language rather tat a dialect of Spanish, When language

Variety dose not have socal prestige, ts grammatical rules are often

‘iematied This ere of the Yule of mutple negation in some English

Aigcass or example. Tle rule allows sentences such as den se

nothing (1 didn't se anythin), which would not occur inthe standard

"The high prestige of the standard leads people to claim that mute

negation is wrong because ie ogkal or miseading. However, we have

‘eve ead Freoch sedis complainabout multpeneptionin standard

French which has Je ma re, containing tvo negative elements

tnd rien, asa teanation ofthe Engl sentence. Moreover, Chaucer

fad no lnbition about the mater when he wrote (in the Probgue to

the Gaterbury Tale)

Ho never yet no ieyaye ne sayde

Inaihiriyf unto no mane wight

(te never ye dat speak no dicourtesy

In ali fe ono kind of penoa")

Infact not content wth double negation, he ues four nepatvesinthese

{wo tines? Malte negation was perfectly acepablein Chaucer's period.

THis mportant for English speaker of whatever variety to ease that

other languages or vate may follow diferent grammatical ues, We

nnotastume tht othe languages or vretes wifi the famework

tthe one we know wel, Thr Kind of mistake was made inthe past by

asea scholars who teed to desibe Enlh i the framework of

atin. For example, the prescriptive rae that I sgt and 8 me

{s wiong comes from assuming tat the dsnction between and me

Imus be the same ae the dneton made in Latin between ero and me.

‘Ths ules ota ll descriptive nce Jisme oscurs often In Enlsh.

any of us fist become svar of the existence of gammatcal res

siteon rom our own when we lear foreign language suchas French,

German o Spanish, We find that, for example, the les of wor order

in these languages are ifferent from English in French adc objet

pronoun must precede the ver rather thaa foo 1.80, fr example,

ce hom i ansutd a Je evs tray“ him se), In German the

innit form of the verb must be placed at the end ofthe ventnce,

2 ENGLISH GRAMMAR FOR TODAY

‘2 that, for example, wilgo tomorow santo a Joh werdemorgon

sehen ‘iterally“ wll tomorrow go) In Spanish subject pronoun or

foun comes after a past participle in question rather tan before, >|

that, for example, Have you forgotten the word? is transated as fle

‘olvidedo ated i polaba? (literal, “Have forgotten you the word?)

"However, French, German and Spanish sl show considerable simaity

to Engh in their grammatical rules, forall four languages belong 10

{he INDO-EUROPEAN group, and have been in cose cultural comtat. In

all four, for example, you can form questions by changing the order of

words inthe sentence. Ths isnot tive of all languages, however in

Japenese, fr example nicht en Indo-Europea naga qucstons

tue formed bythe adtion of particle (ka) atthe end ofthe sentence

‘So Suauksan waar meas" Saruktiplng vie Steuktson

vw imase a? means Is Mes Suz going”

‘Thee examples have served to vtat tat we must avoid precon-

ceptions about the form which grammatical rules wil take in a gven

lnnguage or langage variety. Instead, we can find out what these ules

axe by observing the way people speck or wate in different situations.

‘Once we have done this, we can return a this Book doesn Chapter 11)

{o questions of prescriptive use.

1.5 Grammar and effective communication

‘The maln function of language so communicate with other people. We

said in section | 2 hat thre was o such thingas ood!” or bad grammar

1 is legitimate, however, to distinguish between good and bad com-

‘munication. In her wards, language should not be etlusted according

to wat typeof grammatical rules i follows, but aconding to wheter

1 conveys its mesage effecvely. Is quite posible, for exazple, to

speak oF wit according to the grammatical rules of sandard English,

fd yet to produce langage which unclear or dificult ofolow. This

Can be described asad syle’ and the folowing examples fom witen

English usrate the point

(1). Tris ies pote that aa that frend of mine knows pints

(2) _Taaw stina book tata former teacher of mine thought of mone

@ by cannot dink cold milk thou be bole.

@ ‘ano belonging to 2 lady going abroad with an oak

case and cared les.

(5) The prov of what contribution the public should make to the

swimming poo arose

(6) Shetan given theo in London vp

WHAT GRABBAR IS ANDIS NOT 8

ts interesing to consider why certain sentences are fet tobe ls ue

{sly constructed than other In (1) sod (2) he sentences ate pt

together ina may which makes them diffical to unmveland understand.

For example, in (1) who painted the peture-the gor the ind? Most

‘people wil have fo regead the sentence in order to puzzle out exactly

‘that i's saying ln @) abd (4 to construction ofeach sentence leads

{oan ambiguty: what the Welter intended to sty isnot cles sto.

‘This docs not neces imply that che reader cannot workout the

{tended meaning. You ae ullksy, for instance, to imagine tha the

Tay rather than the mak to be Boded in (3). But you amie at this

nck tn spite of grammar rather than eons ff The grammar

fpeumits «second meaning, which Ike an ftersmage lurks distracting

[the background. In (S) and (6) he dial i that there seems tobe

2 lack of blanc, atophetine in the construction of exch sentence.

{To solve this diffialty, one sould change the order of the words 5

fellows

(5) The problem arose of what contiution the publi should make

fo the swimming Poo

(6a) Shea given up the Job in London

[At this stage we shal not attempt to explain exact what the matter

wrth (I) tis enough to mote that these ae Just three types of dt

Fealy do forming sd sterpeting grammatical sentences,

‘Since using anpuage i 4 sil ts ineitable that some people are

mote ake inthis espect than other. Thar sno nee to ink from

‘ralaton ofthis il” for example, saying that one writer asa beter

‘ipl of writing than srothe. Is etl fortis purpose, tobe aware

ithe grammutclrexources ofthe language, andthe various possibilities

thigh may be open tothe wser who wants to make effective use of the

EEnguage Ia thi way we gan consis contol ovr the skal of using

Tnnguape, This one ofthe rain reasons for learning about pram,

ad weal tues to tn Chapter 12

1.6 Grammar in prose style

[At the other extzema fom sentences (1)-(6 te the products of itera

imasters of pose style, In Iteratre, the resources of the language,

cluding grammar, ueed not only for efficent communication of

Hens, but for effective comrnunication tna broudersese:communicat-

fig an nterpeting people's xpeconce of Me, india an collective

‘This means ting language in special ways, 2 canbe iustated, on

ial sale, by oven a short sentence like the flowing

“ ENGLISH GRAMMAR FORTODAY

(7) To tive ke to love~ all reason Is aglat i, and all healthy

inte frit

(Gere Butler, NoteBooks)

‘The éifcaty of making ease of (7) s quite different from that of

‘aking tense of (1) and (2). An wouual sentiment is exprased ia

ftrikng and unevl wey. This typical of rary expression, rd means

that mich meaning s condensed ito few words, Let us bie con

‘der how grammar contabates 0 the effect, parieulsely through

‘paraletion: the matching of one conseutio wih anther, sma one

igre 13 ca sul representation o this paral

Figure 1.3

wie] lke «| ove

all esion ‘Albay instinct

is is

insti forit

As the diagram shows, sentence (7) i cleverly constructed 90 a8 to

bring ovt to parlelisns. The fit is one of nlarty (2 Be.0

love) an the sesond sone of contrast (al reason. all heathy insti).

‘The paallms are expremed by symmetry in the actual choice and

combination of words, 0 that almom every word inthe wntence is

‘alancod sgncandy against another word. Even the sound of words

hslps to undetine these relationships: the analogy between te and ve

4 emphaased by simlar promuncstion, andthe word like, which

“radiate betwee the wo, esmbles the forme in appearance and the

biter in meaning.

Sentences exit primarily ine ather han ingpace,andso the order

in which words ocour i portant for Lterary effect. Suppose (7) had

read ike tis

(7a) To ei ike to Lore ll heathy instincts fort and all reason

sensi

‘The remalt woul hae bee to sess Yeason'at the expense of stn —

most as i the write were iaviting us all to coms suede, Thi is

|WHATGRAOIAR IS AND ISNOT 5

‘because thar sa general principle (oe 12.23) tat the most newsworthy

fd important Information in sentence tends tobe saved tothe end

Sentence (7), a Butler writs i sop rather than pessimistic

for he plas natin in fumpbaat postion atthe end, adding the

‘word eal for further optimile emphasis The fist par of 7) po-

Vides a further example ofthe saiieance of ordering. Let us iapine

{hat Butler had weiten To love i lke fo ie. In that as he would

be comparing loving with ving’ rather than vce vera As itstands (7)

In effex says: "You know about love being the teumph of heathy

{instinct over feton, don't you" Now Tm telling you that be el is

[ike that? That tho stance Bogine with what we may all shared

{eneal knowledge (the traditional conception of love defyiag reason),

Sd extends thie wellknown ds to new sphere rather, generaies

itt the whole of ie Soi Buller had water "To love js like tole,

the whole effect would have been altered, to the baflement of the

reader,

“Tis extremely simple example shows how much the way we con-

strut sentence - the way we put the parts together ~ an conte

{o the effect makes on a reader of listener. If we want to understand

the wrtues of god writing, whether a studenisof erature, or aswriters

‘urseles, we heed to undertand something the grammatical resources

‘ofthe language, andthe ways in which they may Be exploited,

1.7 Grammar in poetry

“The same appli o poetry Poetry and grammar seem tobe poesapat ~

the one mggestve of “he spark o” Nature's fre the other ofthe cold

tye of analy. Buta poet Would be fools to procaim Tam above

‘gama fori isby parmaticalehoie that many of the speci mean

lage of poetry are schievod. Often these effects show "poeticlience~

‘the poet's acknowledged prilge of deviation from the rulesor conven

tone of everyday Iaguago. Without the rules, of ours, the poet's

{ovation from the rules would lav its communicative forge The fllow-

Ing short poem, on a nun’ taking the ve, shows some ofthe charactet-

fis (In adliion fo thos of mete and thyme) which we may expet

{0 find in the language of poe

@ Heaven-Haven

bre desied to 0

‘Toads where fes no sharp snd ded hal

“And a few les Dow

6 ENGLISH ORAMMAR FOR TODAY

And have sted to be

Where no storms come,

Where th green swell iin he havens dom

‘Aad ot ofthe swing of the wa

(Gera Maniey Hopi)

[Asin (7), but more obviously, word stko up special relationships wth

fone antes because of similis of sound snd meaning, and also be

‘ose of slates of grammatical structure. The fst tendency is best

‘itated by the pan i thee, Haling the Words heaven and haven

‘The second tendency i evident in the marked paral of the two

stanza, az shown in hi elton esto

Ga) hae —edto- And Lhave _edto—

‘Where ‘Where

‘To fields whee Where

ed ‘had

‘We could study, further, the unEngish grammar ofthe second ine (Were

springs not farther thn Where springs do not fai) the inversion of

the normal order of wes inthe thi line (To ll where sno sharp

(and sided hay and the postponement of the adjective dumb othe end

‘of the seventh Hine, Sich unusual Testures of prammar contribute toa

‘range disoiation of words fom tet expected contexts that simple

nd ocdinary words ike sprigs, les, bow, sl! and sing seem 10

[Main sbpovmal Tore. Ir enovgh hore to point out that the poet's

vty in language voles both extra feedom (including freedom to

Aepart from the rues of grammar), and extra discipline (te discipline

tnhich comes withthe superposition of special structures on language)

‘We shal later (Chaper 10) explore the applization of grammar to the

stady of tert, trough specimen anal,

1.8 Conclusion

In this chapter we have almed to provide a backcioth forthe study of|

English grammar, We ben with a attempt to ‘iemythologe the sub-

ject that to dispel rome mlconceptons about grmmas which hae

‘oan prevalent in the pas, ad stl have influence today.

"We showed how the notlon of grammar mus alow for variation in

language, and that We cannot prescribe the form which grammatical

‘les wi take, We thu ejected the possi of evalusting grammar

eal, but went on to show bow language canbe ued fr mote ores

‘effective communication. In Patt Cf this book we wl return to some

Of the points which weave managed totals only briefly and simply

\WHAT GRAMOHAR I$ AND IS NOT "

so far, and we will abo dusete the practical benefits of studying

{Pammitforundertanding out language and wing it mor effectively.

Part B, whic folows, ims to make you avare of your knowledge

‘of how sandard Enplsh i stroctred. We tall be intoducing gram-

‘tial texniology nd techlgues of anayss that wil enable you to

Alesrbe this stroetre Part of understanding grammar i learning how

{oo I, so we would urge you fo work through the exercise i each

‘haptr in oder to apply your new knowledge,

Exercises

vere Lt

‘True fase questionnaire (ots your understanding of the chaptes)

‘The following statements shoal be beled tue or as:

(aenerson 7199)

1. Thestudy of grasumar must include the stay of Latin.

3. Grammar canbe ten aes set of rules Walch we follow when we

tr teagan.

3, We an follow the grammatcalales of ouraatve langage without

Bi

owing them comeioul.

"The tndy of grammar wi improve your spelling.

Grammar ony deals with the ody of wing, because orginally

heat wt’ in Grek

6. Chilren ave tobe propely tutored in ther language if they are

{lear to speak grammatically.

+7, Stuiying grummar voles eraing how people thou speak

I sinaowect to end amntence with prepostion

5, Americas English sens grammatical han Brith Engi

(0, ‘The way we speak depends, among other things om 8 personal

Sharcteais

11, The way We speak to frends is Sentcl tothe way we sesk to

12, Duar inferior to the standard ngaag

13, Pactory workers inthe nor and south of Bala difer more in

fir epecc tha Jo doctors

14, The term TENOR reer the pitchef your voiceina given situation,

1S, Whatever you can some inspeech, you canalio convey n wet,

16, Medsie could be comsered a lanztge domain

[illanguage follow the sane grammatical rls

1a, AURtEneE nck ic to oncertaod mst be ungrammate

19, The ue of language in erature ithe sme as in convertion,

30, Poets icene in offic permstion to write post.

8 ENGLISH GRAMMAR FOR TODAY

arcse 1 (answers om p199)

Qusifiaton of ttences

Sttof the folowing sentences have something “wr

{fo wook out whether each

'A--ungrammatcel in he snse that it doee aot fllowa ule observable

i he lnguags beharour of native speakers of English;

1B “bad etiquette’ from the point of view of prescriptive grammar

Geter

with them, Ty

(© “bad tye" inthe sense tht i doesnot communlsateefecurey

1, Team recommend this candidate for the post for whch he apes

‘vith complete confidence.

2, Taint going nowhere tonight,

3. We'need more comrenersve schools

4, Tovar ornot to was, that be te ask,

$1 Thetelines he dene fens deep down things.

& How ase yous it han long ine that we don't hve heared from

1

8

5

0.

youreain

"given the prevent that ad Boosh in the shop in which I

Fan met the mato whose house weat yesterday.

Him and me ar going othe beach today.

ep sl bpd hh ne tn te ae Wt

"Ta othe sort of Enaish up with which 1 wil ot pat

Exess 1 ansers nd sures on p.200)

dentin categories of ruse ua (set 133)

ewify the categories of language st in test saps of angus, 8

follows

“Tenor formal or iformal

Mode spoken or watt,

Domin sdvertsing,ouralsm, or eligion

‘Beomple After reading this, other central heating ystems wont 10K

fonot.

Tenor: informal, Mode: welten; Domain: advertising,

1. The Senate yesterday announced the creation of» nineman com

Tutt tovenizate th relationship between Bily” Carter 3d

Colonel Qadsatts goverment in Libye.

2, Pine and glory and wislom, thaakapving and honour, rower and

iit, beto ou God forever aad eve! Amen

[WHAT GRAMDIAR I§ AND 1S NOT 9

Anywhere return stil ont SOP.

Contour ing looks sper, it fee mares

"what's likely ¢o happen now? Well the Fepert hasbeen vent co

{he Director of Public Proseation, new of er certain eden,

PART B

ANALYSIS

2

Sentences and their parts

(Grammar ca be bsiely described a6 a set of rules fr constructing and

for analysing sentences, The proves of analysing sentences into th

puts o” CONSTITUENTS isn as PARSING. In thisand the next ie

‘faplers we shall gradually bud up a simplified technique for parsing

English vontences, It parsing sem at first a neptive proces of taking

things to ples, remember that by taking a machine to pices one learns

how it works, Analy and eyntheiae two aspects ofthe sae process

‘ofunderstanding, Thschapter introduces the main concepts of param,

svith examples. you find parts of aia, cw be a comfort to

Tinow that all he Sascations of Chapter 2 wl be dealt with in more

‘et ater on

2.1 Prologue: parts of speech

241 Atos

First, hore i a shor text which may be sten as avery easy general

“knowledge test about English prrnmar. Its purpose is simply to start,

you thinking on the ight lines n some cases, no doubt, this wil mean

Femembering what yt learned may years ago, and hae rarely thought

shout since,

Gta sentences (1)-(4) make alt, in four columns, of the ital

‘hed morés which ae ()) nouns, (i) verb, (i) adjecties, and

Go advebs:

(1) New cars are very expensive nowadey

(2) Tunderstand that even Dacula hates werewobves.

(@)_Lhave wom more rounds of go tha you have hd hot dimer.

{3 Mother Hustard went tothe cupboard, Long viny for food

fonbe ber dos

(©) Now tnt you ave ade thet, my why you afd the word

as you di, Ths wil sguie some Kind of definition of what «

‘ou ave, am adjective ran adverb

23

Pa ENGLISH ORAMMAR FOR TODAY

fyou remember about traditional word chasse, or PARTS OF SPEECH as

they ae called, your Its wil be something ike the following: ca,

Dracus, werewobes, rounds, golf, diners, food and dog ate nouns, are

understand, hates, won, ha went, loking and ge ate verbs; new,

expensive and hora adjectives; ner, nowadays an snl ae ade,

Je wer to exp your it, you may have ud friar defitons

© ‘Armoun ia naming word: it eer to a thing peron, substance,

(‘A veri doing word: it refers tn am aeton*

(Gi) sAn adjective isa word which describes or qualifies 2 noun.”

(is) ‘An adver 2 word which desrbes or qualifies other types of

‘words, such a vebs adjectives and adverbs"

Tig a ety sat ein in ef mn

i Sh deine stl Saupe pc ee

Ss ettrg our gunnar bt es ate (y

‘ot ape te Shaya me ee

oral nt cb es nam ut oct

1 ec Bo efoto aa

Opa he lee Po ae me

Thiet Gut ay edt door oars

‘Rie wen he weld se sting so

tet rahe eo ar ina

sro eee al gf chasm ance

Ara sonra dens Ohta eae

te ia ocean of hse

pt mn a a aed one Nos

Say win wn ln ste Socpon way

to pov boa ont p elon eta ae

‘nina Noa te Soa

te ew var srw eels a et

Sure sand ce hoes ee on We

Tee mon my eter Son anne

Bec gy Be dean ae eat na ee

feo, An wit Tho ova our tt ere

Sie i eS tae Se

a ond pode tara att hohe a

etme pr opt hn Dennen ane

f Basel hed Secchi py one eet

Ne Daan nes er eT e Ra sel al t

‘Bang ka sh ree "a

‘Son hotse enticed fe ae et

SENTENCES AND THEIR PARTS 2s

4 bout many ABSTRACT NOUNS wh ke rd, ated in

ole ev ab'oc an aja reduereacion wee; nee!

{Pease kines doerntdernc; ool

te: abhernocky?

Fe a crehron meaniog in defining word clases, The

Soe cae, iy oben we aoe (many hae noted bet)

Fa de oem ach Lew Cros Jabbersoaty we ant

a ae mnmne words ven thogh te J not know

rang:

asi, an he sity toes

hd gov and sinble inthe wate:

’Amimey were the Bororoves,

‘And the mone rath outgsabe

know fo tne, hat fre and Borogve ae nous tha 2,

Mende tet ata sy and mina edhe.

eas we know? Cartan ot on atount of sing! Rat,

Petey ak wor on thet ottoman ts pstion Bove

NSS GeEIuT eas nie volar pra ein of ou)

Set oe Si sie Dt om een

1 ot Chou ut) at wea 24

mee ence would mit he comps The a ony pasta

seehloh ut ty tow the kind of ites a grata.

San oft pad wh boak on Banat as ©

sage Ta show a sae sl ot pray pe

Sion meaning,

13. Te fn Soman of pant ee

Re Laattten tot oman delons ae fe and ae slo di

To a si ya le eta ga

wet anced etiam oe

Ree re sate un, bn dg ma, We

ie anon ht a nnn he at

ie Tae of ris wd me

cae ee ee an te cj wt

a oe thy ac meg

‘oe a scene seach ne

amt le canon ear Sa

a tir ipo he,

Say asin ot ad gi paws robs

2% [BNGLISHGRANOLAR FOR TODAY

type, hres cages docks nd penguins ae in meres dees

ie! The mine cote of caters wit acy sige ees

‘Sum Jute chase casts oho tale

fon ds ale “dy tan ors, 0 soe num atten?

= othe and ome verb et wey ‘than others. The typical, or

ope, hou a the wich eto pepe sia

{5 te Ingen, nelly to manber smote the he ate

his iden ian Te aot poms with te st os

‘ut ungae aswel, Stary, hey wean wae

though th mast common ve fae enolase

iat folios, then, esl fie when dee penal

soto te words ach yp enrlyraetae e

nae Ta ot weaous t's 2 wlio of he ey

Sound mal aor, oul ee nin

is concept of fue” ear apes nau cing bat

sto to formal specs of ceftion. Fa anes pp oasis

Dalin-sands peal vb hsp tne in bah aca

Gh havea pul may (og ven, fhe whieh hve al

3. suman hr as We wh a ge a

tte,

Gina nt ede palo matenatal sen, bt Bas

smh in common wt bloga yer ett ivlesoaaring

Gitetaand bas fry wg Te ie ty af guns poste

the docile pltypan Thin means ates nat siva

Signy ce of eso i

reenet about wha hte bet aias eta etn ee

‘Exercise 2a] ot pea

22. The hierarchy of units

‘The SENTENCE isthe largest unt of language that we shal be concerned

ih ere sentence conponed of nar ut, CLAUSES, PASS

GRAMMATICAL UNITS OF ENGLISH syMBOL,

Sentence +

Cause

so B

Word h

For convenience in parg, we ge each grammatical category we ne

trodue shorthand symbol, The symbols nd abbrevtons aed nts

‘book ae sted om pape 3,

SENTENCES AND THEIR PARTS a

“The wnits SENTENCE and WORD need tl introduction as they ae

fuiy dearly repeonted in ove wsting system. In general we shall

enti them acsording tothe usual convention: that

‘be denied by an ntl capital letter anda final fllstop (or question.

‘attr exclamation, and a word wil be delimited, for most pur

pws, by = space (or punctuation mark ther than a hyphen oF apo

pte) on en e

72S the ipl unio which sentences ae compo. A

scotence may const of one or mare causes, For example:

(5) tack Syrak wul eat 2 ft

‘This, standing on its owa, is a sntence. Bt (5) can also occur as part

of larger une

(©) Usok Spat cout et no fat), ahs wife could eat n ea,

(5) Brey eld knows (tht Jack Spret could ext o fa

Here (6) and (7) ar sentence, but the parts of them in quae rackets

gnats are uns intermediate between clase and word. Th

comin of nlve words, but these words are grouped ito four phases:

(8) (By Uncle Olaf vas munching) (ls peach) (with lsh),

0 creas meat

teres aaa ae

aca me aaa ate

aaa cermrmere as

eens

Se ate

‘Aclause consist of one or more phrases

‘Aphmse consist of one or more words

Lower # Avo

; tant wo otc that we ee sg i’ 2d ow int

Tella! wu wees that wit ofthe ight const

ag ‘A sentence const of one or mare claies

1 put soe that thos comention a aot aves flow Iwan 1

Ie Wi ded we era? Hota a Hee Wh You a toa

ee ee he al th daar wl cao 09

Srpunl'ns out €1, we sow sia a ree ate

Sando eae ware me olay on,

RESIST Soto desta ete inne wd

8 ENGLISH ORAMBAR FOR TODAY

of one or more of the units of the next lower rank, Soa seatenes cas

‘Sesto ony oe cane center lt Sr SENTENCES)

se ‘only one word. Compare sentence (8) with

(6) {(OtaN (munch) (peaches) (contented)

The whole of hs etence ia sgl clases by the square

‘rackets and each word ao comnis «pat Gn toed aca

For hat iatter, a wel ten an cont single wud: Shon

sentence consining fone ane cosine Pras cos,

‘A ft lactis concept fren may sem ane but the foow-

ing analog may belp fo cay Er nother human setety at

ting, bt exting te cold op an ale of our any maa,

court ping mouthf Amel my cont of one or more ne

urea cour may soa of oor mre tan one Sling as

tclping may const of one or moe than one moutful Sock sak

ssl adaptable enough to azount for wile wrt of human stag

‘avon aa tom aserensnure tanga ich ony ase ee

‘ison heiingy oa re snack whe, Italy someone haste

{0 et Smythe rank sae of gama scout for awe oops

of ngage beheour.Obvouty, the rank of nt not eceay

feet eof anos an, ees

ens of oly for Words wheres he aun qarernces

tC), wih of omer a, con smn seen werd

23° Grammatical notations

For both daity and brevity, it i estentlto ave away of represent

ing grammatical structure on paper. la fact, it is wslul to have two

«ferent graphic notations: bracketing and se dingrems,

23.1 Bracketing

Wiohave already usd a simple wet of BRACKETING conventions

(©) Sentences ae marked with an tcp ter andl al

(©) Cates are enclosed in square brackets: [].

(o) Phrases are enciowed in ound brackets: (),

(© Words ae separetd by spaces

(6) IE we need to separate the grammatical components of words, we

conse dash:

SENTENCES AND THEIR PARTS »

So in (@)-(L1) we have as complete patsng as can be managed at

resent

(©) (Our land-Iady) (keep) (a sttt—ed moot) (in er atti]

(10) [(Uncle Oia) seage—iy) (vous) (isnt peach).

(11 tetey) Coe plying) (Assnad (tome) (next wee]

‘Novice that ein They're playing (11) belongs with plying rather than

with Tey, To se thi, we expand "eto are, whlch early belongs 0

the verb pase are playing.

igrams

{Tae bacetingy of ©)-(11) ae easy to use but they do mot ve ery

‘Sear visa petre ofthe elation between constituents. Por this, when

ive ant fo, we can replace the brackets by a TREE DIAGRAM (32

Pipe 2.1,

vewe2s

: ®

t a

r4

Wo Wo Wo Wo Wo Wo WoWo Wo Wo

fee eee]

(Gucland—lady) (Keeps) (@ stuff—e moose) (inher ate)

symbol Cl ete which we nodule ae he we as

anus Tor rds de te, tur al os of he sae ak Gt

‘fon on fet od) ype these lov he Bach

amie ne eps tn of wot for sel,

SEERA cor te dupam mane Toe pn Our indy

ont wo words te Ouran ens

‘The conventions of bracketing and diagramming sould be our sve

and no our masters we shuld oe them only to show Whats pertinent

for our purpose. For sxampl, ifs sentence contains a single clause it

‘soften unnecessary to show the dause lee, and its often unnecessary

30 _ENGLISHGRAMBIAR FOR TODAY

to label the words. The tre shown ln Figure 22, which may be called

fn ABBREVIATED tre diagam, show some simplifications,

Figure 22

Se sefct

Uncle Olaf samgely devoured. is sth peach Wo

We may een want o snp hag een furs, an pods an

[UNLABELLED tree diagram (see Figure 2.3), ir

Figure 23

Se

‘They “e plying Arenal at home next week

‘Thus we can we the notations lexbly,to show whatever information|

‘we consider important. But it aso important tobe abe odo com:

plete parsing when necessary, and for this, we ned tobe abl Yo raw a

FULLY LABELLED tee diagiam, suc as Figue 2.1, where every con

stunt labaled. [Now try Exeris 2.)

24 Using tests

in bracketing and drawing te dagrme we fav toot fr pari

‘cil ene a mo dar at we cata

{athe pueture of sentence macly by pase Sserigi weneed

‘to investigate actively the relations between it 8 by using various

GRAMMATICAL TESTS, eee

242 ei

ong (11) we exo re nto, ad 0 made tear

tht eae epante ve blaping tte a pleat

SENTENCES AND THEIR ARTS 3

with They, We can sso expand a word by adding ater words 910

{how tha ihe word isacting aes phrase. For example, eachof the words

fof Ge) canbe expanded ito a word group"

(2) [ (Olaf) (munchea) (peaches) (contented) }

(88) {conte Ota) (has munehed) (A peaches) (ery contetell)]-

Such additions, although they ad something to the meaing, do not

‘hangs the relation bse the prs of the sentence. Hence theround

‘rackets in (8) correctly show (Ol), (munched), et, 8 phrases, ke

the phrases of 8).

242. Substttion tests

Sometimes, een though we canpot use an expansion text, by sbstitt-

figs word sequence for a word We can se thatthe word actly

behaving asa pre, For nstanc, in (01) we marked They ané Arsenal

se pais:

(it0) (They) ate paying) (Arsenal) (at home (next wee)

[And to help show that ths analysis scorect, we can replace cach of|

‘hos constituents by a Mord group having the same Function, anda

sar meaning

(118) (Thee team are playing) (our team) (at home) (nent weak)!

243. Sobuaction tests

‘Tie opposte of an expansion test a subtraction test, i. omitting

Tome part ofa construction, In Jabberwocky in 21.2, tone inthe

{ly foves was secogised. at « coun, and this in pat was because

{ation tells ws tht fore (athout the -s) would als be grammatical

Equally (10), we marked the ed asa separate grammatieal sfx of

‘rou edad this partly jostied by the fact that the remaining

‘Sart of the word, devours el capable of standing alone a soparate

word,

244. Movement tests

{in (10), Unte Ole sragey devoured his sth peach we ete sary

{aerate pr ther tana prt of pe sagt dvr,

habs man becuse sorely can be moved ceewhore inthe case,

+ onthe we of he ple foowng am 3:21.94, mn 115, 9.17

2 ENGLISH GRAMMAR FOR TODAY

‘without noticeably changing is meaning or function inthe clase, and

‘without dragging devoured with tt

(4100) {Saragey) (Uncle Ota (devoured) (i sath peach).

‘Thae tests wil be refined as we go, and at the moment must be used

pith caution. Also bear in mind that, because grammatical eaeporet

ave fuzzy edge, one testis ruely enough: we often have to tly on

{A mumber of diferent tet in desing which analy isthe covtest or

best one, Nevertheless, thetstsare already uefa and thiss parila

ident in recogisig types of pase. Each phate dss has Keyword?

spss csoeml 1, a whieh provides it with sme. For example,

{5 (12) the ‘keywords’ of the phrses are follows:

a oo adjetve adres

Anat Gin) (hs sehed) ther samy). Gust rected)

own verb sijectve adeeb

phase phane ine Phrase

‘And we can se that these words are esentil othe structure, ia that if

se reduce the sentence to a minimum by subtraction or ubattion,

‘we end up with them lone

(128) {CGinays (soomed) (grumpy) (recent

IE we want to indicate which constituents ae optional, we can place

‘them in erly backs asia (128)

(120) [((Aunt} Glad (Qas) seemed (ate) grumpy)

Guat recent)

(Now try Bxercte 20)

2.8 Formand function

‘This brings us to the general qutstion oF how to easy grammatical

nits, To explain how sentences are constructed, it so! enough

‘entity consituets such a clases, phrases and words; we ts oad

to Mentiy thes as belonging to various classes,

251. fom ass

‘se hve en wd edie ino word cae so 0,

Se Gn A

nts phn (NP ver pre (VP deve pas IAD) sed

rs (io gene prot (OP and pid pie ae

SENTENCES AND THEIR PARTS 3

hepa ead worl casita 032,445)

Forthe moment, rte hat on eon why we ne 0 ety ich

‘as to xpi he orden whlch lena th tense cat

ital aad to pth eo @) ito ay oe

2) (Orla (ae ast mooi) Un be a),

(G0) Stocco (ested soon) urna her st)

{52} “Nae moom) en in er ot (ur wa)

Nor would itt pt the worn any oer nr within he ae:

(20) [Landay 0 (ee ae moon) (a ati)

Te tse dram shown i Fg 24, aap fom wntenc (1),

Sows how the exon inaraton soa he nd wor casa be