Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fowden Gart The Revival of Monasticism On Athos

Uploaded by

ANDROMEDA19740 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views3 pagesαθος

Original Title

Fowden Gart the Revival of Monasticism on Athos

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentαθος

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views3 pagesFowden Gart The Revival of Monasticism On Athos

Uploaded by

ANDROMEDA1974αθος

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

the faith of people in the camps and of religious services whispered secretly

by groups of mien as they rested on the grass. In the solitude Dr. Levitin was

able to pray and recite the services of the Russian Orthodox Church to himself

and at such times he had a vision of the ecumenical nature of the Church—

the One Body.

OF the Conference, too, prayer and meditation formed an integral part

of our lives. Each day began either with an Orthodox Liturgy or an Anglican

Holy Communion (or, once, a Roman Mass), and in the evening there was

either Orthodox Vespers or abbreviated Evening Prayer. The Orthodox

worship T found very helpful and as the week progressed I was happy to find

mysolf mnaking the transition from a spectator to one who could pray the

services and make much of them his own, I am sorry to say I was less at home

with the Anglican services—in their ceremonial they owed much to nineteenth

century borrowings from Rome and frequently contained features (uch as

devotion to Mary) which are not altogether typical of traditional Anglican

teaching or practice. Perhaps it is a present challenge to the Fellowship to seek

to bring a wider spectrum of Anglicanism into contact with Orthodoxy? There

were alo meditations in the morning and frequently again at night : those of

Fr, Lev Gillet I found especially helpful. Thus the whole Conference was

undergirded by an atmosphere of prayer and the sense of being God's people

in Christ, which, for me at Ieast, gave an added depth and purpose to our

activities. It was no doubt also this underlying spiritual awareness that ensured

that the Conference really was a meeting of people in fellowship. The atmo-

sphere was very friendly and accepting, and the many meetings and con-

versations were as important as the official lectures. There are several people

from whom I learned something more of Christian love during the week, but

T will mention only three. The first was Isa Gulean, a young Syrian Orthodox

from Turkey, who was able to talk without any bitterness of all that his

Church has suffered from both Islam and the Western Church. The other two

are Nicolas and Militza Zernov, in whom I began to see what the Orthodox

mean when they talk of man as capable of becoming an icon of Christ. My

fe is the richer for having met them.

Finally, I must express my gratitude to Ganon Allchin and all those who

helped plan and run the Conference, particularly of course Rev. Gareth Evans

who, in some of the hottest weather of the year, coped very efficiently yet

unobtrusively with the problems of administering such a large and unruly

body as we were,

ignorance and prejudice between Christians and enabling them to see that

in Christ they are children of the same Heavenly Father who ‘s good and

loves mankind’,

130

jong may the Fellowship continue its part in the task, not,

so much of healing the divisions within the Church, but of overcoming‘

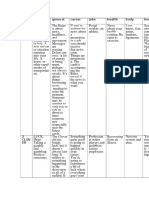

THE REVIVAL OF MONASTICISM

ON ATHOS

by GARTH L. FOWDEN

On July 23rd, 1974, Greece witnessed 2 remarkable and still in many ways

mysterious revolution in its political life. In a dramatic reversal of fortunes

an older generation of politicians returned to govern a country where seven

years of authoritarian rul.—a curious blend of oriental conservatism, even

prudery, with a constant exposure to "ie cultural values of the regime’s main

external ally, the Americans—had done much to undermine the Greece they

had known before their exile from political life. In a short article written a

year before the fall of the ‘Junta’, and published in the Winter 1973 issue of

Sobornost, I drew attention to the encouraging signs of a revival of the mon-

astic life on the Holy Mountain of Athos, while suggesting at the same time

that the failure of outsiders to understand the value of its unique zhythms of

life might lead to a dangerous jsulation from and vulnerability to the outside

world—to its becoming an island in time. Two years later, both the internal

condition and the external context of the Athonite communities have changed

and developed sufficiently to warrant a brief second glance at the problem.

‘The two decayed monasteries which had already been fully revived in

1973 have since consolidated their position, The pioneering community at

Stavronikita now consists of fifteen monks and three novices, under their

distinguished abbot Basileios. Although this community is small even by

Athonite standards, its monastery is small too, and no great expansion is anti-

cipated in the near future, although it has recently acquired two foreign

members, one English and one Swiss. Its somewhat intellectual character led

to initial suspicions of radicalism on the part of the always conservative

inhabitants of the Holy Mountain, but gradually the community has been

able to show’ that one of the best ways of strengthening traditions is by under-

standing them—a point which will doubtless be best appreciated by visitors

used to the off-hand manner in which older monks are still sometimes inclined

to treat the artistic treasures in thelr care.

In similar manner, Philotheou now has forty-five members, and is expecting

more novices, Without the intellectual reputation of Stavronibita, it nonethe-

less asserts what it conceives to be the purest and strictest traditions of Greek

monasticism. Its refusal to admit non-Orthodox to the common meals, or

beyond the exonarthex of the church during services, is apt to prove puzzling

to the Western visitor but one monk remarked during a recent visit that he

found equally puzzling the arrogance of non-Orthodox visitors in not attend

ing services for this reason, for the life of the monastery is the paradigm of

Christian truth, the trunk of dogma of which Rome is but the largest branch,

and the Protestant Churches subordinate off-shoots, This is in essence the same

attitude as that which finds its most rigid and legalistic expression in the zealot

131

Athos Library

Aytopertixh BiBALoBrhKN

community of Esphigmenou, where anti-ecumenism and Old Calendarism are

treated as items of faith. That such an outlook is nonetheless a minority view

cven on the Holy Mountain was demonstrated by the failure of the other

houses to rally to the support of Esphigmenou when in 1974 it placed itself

ina state of siege and refused to receive the representatives of the Ecumenical

Patriarch, Although the monastery is still boycotting the meetings of the, Holy

Community, nobody any longer takes their slogan of ‘Orthodoxy or Death’

very seriously, and, in an almost Anglican spirit of compromise, the affair is

being allowed to die quietly.

‘A very different spirit pervades the monastery of Simonopetra, until

Christmas 1973 one of the most decayed of all Athonite houses, but now

entirely revivified through the arrival of the group of forty young monks,

mostly in their twenties and thirties, formerly living in the Monastery of the

Metamorphosis at Meteora, Hounded from there by the pressure of

tourism, they were welcomed with open arms at Simonopetra, The ori

community of ten aged momks, whose abbot had just died, immediately elected

the leader of the Meteoran group, Fr. Aimilianos, as its new head. This smooth

transition was much facilitated by the fact that Simonopetra was already a

coenobion, whereas at Philotheou the process had been less happy because the

original community had’ been idiorhythmic. The old monks of Simonopetra

greeted the new arrivals with a heart-felt joy; they would even go out and

bring flowers as tokens of. their gratitude, while in their turn the younger men,

many of them university-educated either in Greece or even in some cases

abroad, say that they seeino reason why the differences which separate them

from their older brethren should not be overcome through love and the grace

of God. For as Fr, Serapion remarks: ‘Monks are like children. They play,

and never dream their father may have problems.”

‘The younger generation of monks at Simonopetra puts its skills and

enthusiasm to good use and shows its sense of duty towards the wider life of

the Holy Mountain by taking a particular interest in the administration of the

monastic state. In 1975 it supplied both the Secretary and Under-Secretary of

the Holy Community, while foreign visitors to Simonopetra are made particu-

larly welcome by those of the community who speak foreign Languages. More

over, like Stavronikita, the house has several foreign monks or novices,

‘The monastic revival on Athos is not however confined to the three mon

asteries of Stavronikita, Philotheou, and Simonopetra. Two other houses,

Grigoriou and Koutloumousiou, have received infusions of fresh blood without

as yet undergoing a fundamental change in character. At Grigoriou, the

election of a new abbot has led to the arrival since July 1974 of fifteen new

monks, including one Peruvian, while at Koutloumousiou, another house of

little reputation in recent years, the strength of the community has now risen

to fifteen after the arrival early in June 1975 of about eight new monks,

though not this time from outside the Holy Mountain—sevaral of them came

Another aspect of the new spirit abroad on the Holy

132

Mountain is che formation of what might be described as pressure gro

within certain idiorhythmic houses, aiming at a change-over to cocnobitic

status, It is in the nature of the monastic organism, that such a fundamental

change, to be effected from within rather than (as in the case of Philotheou)

through the arrival of new forces from without, must be undertaken with

infinite caution and carefulness. In the Serbian monastery of Chilandari eight

monis (about a third of the total) are in favour of the change, and try to eat

together when possible. The attitudes of the others vary, but one of them

perfectly expressed the essence of the problem by assuring the present writer

that the coenobitic system was of course the ideal, but that for himself he

preferred the freedom (and the far from arduous character, if judged by

* coenobitic standards) of idiorhythmic life, Nonetheless, Chilazdari is lucky in

being an idiorythmic house with an excellent spirit, which perhaps it owes to

the popular esteem it enjoys among the Christians of Yugoslavia—more than

can be said for any Greek house. Possibly it is ultimately of greater significance

that there is said to be a similar pro-coenobitic group in the wealthy and

tourist-suffocated Megisti Lavra.

‘The spectacular changes of fortune enjoyed by a few monasteries during

the last eight years, and the hopes for the future nursed by others, should not

blind us to the quieter, older-established virtues of houses like Dionysiow and

Aghiou Pavlou, and of the sketes and other dependencies. Indeed, those monks

who live outside the walls of the twenty ruling monasteries enjoy a great

advantage over their brothers in that they are largely free from the intrusions

of the tourist. Few visitors will ever penetrate to the idyllic kellion of Moly-

vokklisia, for example, though it lies but fifteen minutes’ walk from Karyes.

‘A dependency of Chilandari, this rambling dwelling with its mediaeval chapel

land exquisite frescoes now houses a recently-arrived group of about ten Greck

monks, somé of them icon-painters, living a life of a moving simplicity that

would’ scarcely be conceivable amidst the distractions and faded glories of

prestigious monasteries on the beaten tourist trac

Ultimately though, it is the individual charismatic leader, the spiritual

father (gerontas), on whom the life of the Holy Mountain hinges. It is the

abbot who sets the tone of his monastery, and if he is known as a master of

the spiritual life, he will attract to his house men of scrious purpose and

dedication, Deprived of such a leader, a community may easily lose its

spiritual impetus, even though it continues to preserve the outward forms.

Thus the revival of Grigoriou has been due entirely to its new abbot, while

__ the respect accorded to Dionysiou is due largely to its nonagenarian abbot and

spiritual father, whose reputation extends far beyond the Holy Mountain, and

who has been described by a monk of another monastery as ‘a man of vast

spiritual culture’. Similarly, the monks of Simonopetra might be described

without undue exaggeration as simply the disciples of their abbot, Fr.

Aimilianos—their chief loyalty is to him and to the place in which they happen

to find themselves, be it the Meteora or the Holy Mountain. Conversely, the

133

Ate: Library

Ayiopercixth BuBALoBr}KN

same point is the chief argument against the idiorythmic system, which by

definition excludes the office of abbot, and creates an atmosphere in which

the maa of spiritual distinction may well exist, but searcely lead,

It need hardly be added that the tendency of the outside world to judge

the Holy Mountain of Athos only in terms of what it can offer as a landscape,

or as a repository of Byzantine art, demonstrates a complete ignorance of the

value to mankind of a spiritual garden, and of the preservation of some other

criterion by which the doings of the modern world may be judged. But equally

it would be wrong to concentrate so much on the inner life of the Holy

Mountsin as to lose sight of the problem which, at long last, the monks them-

selves sre beginning to ponder—how to adjust the traditional life of the

Athonite communities sufficiently to allow them to continue looking outwards,

and in turn to be a beacon to which the world itself will look.

‘The first and basic aspect of the problem is how to maintain the total

number of monks on the Holy Mountain at a reasonable level, especially in

view of the difficulty of finding and paying lay workers to assist in the every-

day upleep of the monasteries, and in the exploitation. of the forests on which

the monks largely depend for their livelihood, Over the last five years the

number of monks on Athos has actually risen from about 1,140 to about 1,200,

thus reversing the fall in numbers that had been more or Jess constant since

the end of the First World War. However, this total could be larger if more

monks were to come from the communist countries—the Patriarch of Moscow

recently requested permission from the Holy Community for twenty-five to

come from Russia, but though the Community (of which the overwhelming

majority is of course Greek) was agreeable, Athens allowed permits only for

ight, Tt remains to be seen whether the atmosphere of détente now prevailing

between Greece and the communist bloc will improve this situation, but it is

more likely that the policy of the Greek government towards the Holy Moun-

tain is dictated by internal rather than foreign policy (in which the fate of a

handful of monks can hardly weigh very heavily),

‘On the other hand, the change of regime in Athens has already had at

least two beneficial. results for the Athonite community. Firstly, the new civil

governor, a professor of theology from the University of Thessaloniki, is vastly

more sympathetic, and therefore respected, than was his predecessor, while

secondly, a number of monks or novices of western oricin have at last been

granted the residence permits which they were denied under the Junta. As has

already been noted, several houses (including Stavronikita, Simonopetra,

Grigoriou and the skete of the Prophet Elijah) now have one or two members _

of western European or American origin, amounting to perhaps ten on the

whole peninsula. The fact that these men are of western culture, and often

converts from other branches of Christianity, is gradually adding an intriguing

new dimension to the life of the Holy Mountain,

‘The whole question of what role the Greek state will play in the future of

Athos is so complex as to be immune to summary. Despite this, the isolated

134

‘observations of an outsider may occasionally throw some light. The contribu-

tions made by the Ministry of Culture to, for example, the restoration

programme and new museum just completed at Chilandari, and to the clear

ing of the Theophanes frescoes in the katholikon of Stavronikita, must unavoid-

ably strengthen the State's hand if it should wish in some way to make the

artistic treasures of Athos more accessible. Equally, the reluctance of the

government to approve (let alone initiate) positive steps to curb casual tourisia

gives ground for disquiet. On the other hand, even if only for financiel

reasons, there seems to be little chance of new roads being made on the

peninsula in the near future, while the idea is beginning to be broached of aa

Athonite museum, to be built possibly on the border, or in Thessaloniki, for

* exhibitions of icons and other works of art—a wise concession to the feeling

that the treasures of Athos should be made more easily accessible that they are

at the moment, and a logical extension of the efforts of the Patriarchal Insti-

tute for Patristic Studies at Moni Viatadon in Thessaloniki to make micro-

films of the Athonite manuscripts available to scholars throughout the world.

These comments are intended as a progress-report, and by their nature

can have no conclusion, At one level, it is impossible to separate the Athonite

community irom the society which produces most of its members. One has

only to glance at a newspaper stand or a cinema-hoarding in any Greek town

to be amazed at the increased rapidity with which the cheapest features of

Western popular culture have been imitated during the first year of the

restored democracy. Even more significantly, mass-education has been much

expanded over the last two decades so that by now even the simplest villagers,

are inclined on the one hand to question their own traditions, but on the other

to accept without question whatever is foreign, (The exaggerated popular

enthusiasm for the cultural exports of the communist countries, in reaction to

the rabid anti-communism of the Junta, is a good example of this.) Mon

asticism, of course, is an important part of the tradition that is being ques.

tioned, though conversely, as long as Greek men and women continue to feel

the religious vocation, the standards of monastic life will rise in step with

those of society at large. This brings us to the second level at which the

problem must be considered ; for to enter a monastery is to forget the world,

and on Athos at least this injunction is taken very seriously. Is it therefore

possible to explain the revival of monasticism on Athos simply in terms of

changes in Greek society, or is there more to it than that? To this question

there can be no sure answer, but if the West is any standard by which to

judge, monasticism thrives these days in spite rather than because of society,

as an expression of the desire to remould rather than to reaffirm it. Education,

by definition a process of induction into received cultural values, js not itself

enough to inspire young men to the life of self-denial, and if the Holy Moun-

tain continues to exercise its fascination over them, it is to the soul rather than

the mind that it makes its first appeal.

Athens, August 1975 *

Athos Library

185 Ayiopetcuxt BiBALOBHKN

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Modern Sex Magick Secrets of Erotic SpiritualityDocument397 pagesModern Sex Magick Secrets of Erotic SpiritualityBalleyaCardenas100% (3)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Basic Sex Magick TechniquesDocument4 pagesBasic Sex Magick TechniquesANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- Basic Sex Magick TechniquesDocument4 pagesBasic Sex Magick TechniquesANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ashcroft-Nowicki - Ritual Magic WorkbookDocument256 pagesAshcroft-Nowicki - Ritual Magic Workbookanon-660020100% (7)

- Ashcroft-Nowicki - Ritual Magic WorkbookDocument256 pagesAshcroft-Nowicki - Ritual Magic Workbookanon-660020100% (7)

- Enochian Hexagram RitualDocument11 pagesEnochian Hexagram RitualPaul ShawNo ratings yet

- Ashcroft-Nowicki - Ritual Magic WorkbookDocument256 pagesAshcroft-Nowicki - Ritual Magic Workbookanon-660020100% (7)

- Lenormand CombinationsDocument57 pagesLenormand CombinationsANDROMEDA1974100% (3)

- Herbs PDFDocument23 pagesHerbs PDFJosh Ninetythree SandsNo ratings yet

- Manual of Cheirosophy PDFDocument330 pagesManual of Cheirosophy PDFGigi Lombard100% (1)

- WitchcraftDocument96 pagesWitchcraftShakala86% (7)

- Complete Book of Love Spells PDFDocument271 pagesComplete Book of Love Spells PDFANDROMEDA197450% (2)

- Dictionary of The Gods PDFDocument15 pagesDictionary of The Gods PDFGigi LombardNo ratings yet

- Bats MagicDocument5 pagesBats MagicANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- Course Tarot Spells TalismansDocument52 pagesCourse Tarot Spells TalismansJames Driscoll100% (1)

- Eliphas LeviDocument2 pagesEliphas LeviANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- The Secret WitchDocument62 pagesThe Secret Witchdavet5562151100% (1)

- Course Tarot Spells TalismansDocument52 pagesCourse Tarot Spells TalismansJames Driscoll100% (1)

- Dictionary of The Gods PDFDocument15 pagesDictionary of The Gods PDFGigi LombardNo ratings yet

- Sex Magic 101 PDFDocument58 pagesSex Magic 101 PDFANDROMEDA197467% (3)

- Κομίνης Βίοι Αγίου Αθανασίου Αθωνίτου PDFDocument14 pagesΚομίνης Βίοι Αγίου Αθανασίου Αθωνίτου PDFANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- Charalampides PDFDocument14 pagesCharalampides PDFANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- DemonographiaDocument30 pagesDemonographiaEnomed MordredNo ratings yet

- Tristan and Isolde Piano PDFDocument7 pagesTristan and Isolde Piano PDFANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- P. Thoma PDFDocument18 pagesP. Thoma PDFANDROMEDA1974No ratings yet

- Sonata in A Minor For Solo FluteDocument7 pagesSonata in A Minor For Solo FlutegaborkNo ratings yet

- DemonographiaDocument30 pagesDemonographiaEnomed MordredNo ratings yet

- Michael Jackson Last Will and TestamentDocument5 pagesMichael Jackson Last Will and Testamentfrajam79100% (6)