Professional Documents

Culture Documents

By Bruce M. Thomson, Timothy J. D e Young, and Constance J. Meadowcroft

By Bruce M. Thomson, Timothy J. D e Young, and Constance J. Meadowcroft

Uploaded by

Junaid AhmadOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

By Bruce M. Thomson, Timothy J. D e Young, and Constance J. Meadowcroft

By Bruce M. Thomson, Timothy J. D e Young, and Constance J. Meadowcroft

Uploaded by

Junaid AhmadCopyright:

Available Formats

ENGINEER ROLES IN PUBLIC

PARTICIPATION PROCESS

By Bruce M. Thomson, 1 Timothy J. D e Young, 2

and Constance J. Meadowcroft 3

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

ABSTRACT: Engineers often are key participants in required public participation

processes. A case in point is the preparation of an Environmental Impact State-

ment which usually involves engineers as representatives of governmental

agencies or as professional consultants. A less common but equally important

role for the engineer is as a member of an advisory committee or as a voluntary

participant in public hearings. A case study of a recently completed EIS process

involving the expansion of Albuquerque, New Mexico's wastewater collection

and treatment facilities suggests a number of ways that engineers in each of

these roles might improve their effectiveness. Increased voluntary participation

by citizen engineers is recommended as an effective means to improve the pub-

lic participation process as well as to enhance the reputation of the engineering

profession.

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, much legislation has been passed at all levels of gov-

ernment that requires formal mechanisms for public participation in public

policy decisions having significant social and environmental impacts.

Citizen participation now plays an important role in the development

and realization of large, complex projects. One of the most visible public

participation programs is the Federal Environmental Impact Statement

(EIS) process established by the National Environmental Protection Act

of 1970 (NEPA). An active and thorough public participation program

is a major facet of NEPA. Formal public hearings, opportunities for writ-

ten comments on draft EIS reports, and in some cases the formulation

of a Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC) are key requirements of the EIS

process.

In virtually every instance, an EIS involves complex and controversial

issues. Since many of the issues include significant technical aspects,

technically competent individuals, especially engineers, are often key

participants. Unfortunately, the public participation process can be quite

frustrating to many engineers. Seemingly endless public meetings may

try the patience of a project engineer trying to complete a project in a

timely and efficient manner. Domination of hearings by single-interest

constituencies may also discourage participation by outside engineers.

However, barring a dramatic change in public sentiment, public partic-

ipation will continue to play a crucial role in the EIS process. Engineers

'Asst.

2

Prof., Dept. of Civ. Engrg., Univ. of New Mexico, Albuquerque, N.M.

Asst. Prof, of Public Administration, Div. of Public Administration, Univ. of

New

3

Mexico, Albuquerque, N.M.

Grad. Student, Div. of Public Administration, Univ. of New Mexico, Albu-

querque, N.M.

Note.Discussion open until December 1, 1983. To extend the closing date

one month, a written request must be filed with the ASCE Manager of Technical

and Professional Publications. The manuscript for this paper was submitted for

review and possible publication on October 8, 1982. This paper is part of the

Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering, Vol. 109, No. 3, July, 1983. ASCE,

ISSN 0733-9380/83/0003-0214/$01.00. Paper No. 18086.

214

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

therefore must learn to interact constructively and effectively with the

divergent interests likely to be involved.

In the context of describing an EIS process recently conducted in Al-

buquerque, New Mexico, this paper explores the roles which the engi-

neer may assume in the public participation process. Various roles are

identified and a number of observations and suggestions are presented

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

to improve the effectiveness of engineers.

Project Description.The City of Albuquerque, like many cities of the

Southwest, has experienced considerable growth in recent years. To ac-

comodate such growth, a major planning effort directed at wastewater

collection and treatment facilities was undertaken by the City in 1975.

A facilities plan was completed which proposed the upgrading and ex-

panding of the existing system in order to handle growth through the

year 2000. Since federal funding for the project was available, an EIS

was prepared and published in 1977. As approved by the Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA), the plan called for disposal of sludge gener-

ated in the treatment process by application on city-owned parks, con-

tinuing a practice of almost 20 years. Subsequent to the publication of

this EIS, however, new federal regulations were promulgated which re-

quired that a Process to Significantly Reduce Pathogens must be imple-

mented prior to application of sludge on public access areas (40 CFR

257.3-6). In other words, a method of disinfection was mandated to con-

trol pathogenic organisms.

In December of 1980, the City prepared an amendment to the facilities

plan to address the new disinfection requirements. This amendment,

the Phase II Expansion Program Engineering Report, called for the dis-

infection of dried sludge using gamma irradiation of Cesium-137, a by-

product of government nuclear programs. (This report is known locally

as the Balloon Report due to the striking cover photograph of one of

Albuquerque's famous hot air balloons.) In the Balloon Report, the City

proposed that the sludge be piped five miles from the treatment facility

to vacant city-owned land. The sludge then would be dried to 40% solids

content and loaded onto a conveyor bucket assembly which would pass

it by the sealed Cs-137 source plaques. Current design criteria estab-

lished under the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) call

for a radiation dose of one mega-rad.

Albuquerque would appear to be an ideal candidate to become the

first municipality in the United States to irradiate its sludge with Cs-137

since much of the technology for this process was developed by nearby

Sandia National Laboratories (SNL). In fact, SNL has successfully op-

erated an eight ton per day pilot plant in Albuquerque for over four

years. In comparison, the proposed facility will eventually handle 30 tons

of dry sludge per day.

The changes in the sludge management portion of the City's proposal

were deemed by EPA to be sufficiently significant to warrant a Supple-

mental EIS. A full-scale public participation program became a necessary

component of the Supplemental EIS, in part due to the controversial

nature of the City's sludgeirradiation proposal. A flow chart illustrating

the major steps in the planning process is presented in Fig. 1.

Public Participation Program.Coordinated by the Water Resources

Department of the City of Albuquerque, the public participation pro-

215

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

Facilities Plan

1975-1976

Publication of EIS

1977

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

New Regulations on

Land Application of Sludge

4 0 CFR 257. 3 - 6

1979

Balloon Report

1980

Supplemental Draft EIS Public Participation Program

1981 1980- 1981

Final Public Hearing

Nov. 1981

Final EIS Record

, of Decision

1982

FIG. 1.Major Steps in Planning Sludge Treatment and Disposal System

gram consisted of a joint effort among Federal, State and local levels of

government. In order to educate the public and receive their input, both

formal public meetings and less formal Citizen Advisory Committee (CAC)

meetings were held spanning a period of over one year. Table 1 provides

a summary of the public participation meeting schedule.

As a primary forum for public input, the CAC was a major element

of the public participation effort. The committee was organized in De-

cember of 1980 to study the feasible options of sludge treatment and

TABLE 1.Summary of Public Participation Program Meeting Schedule

Meeting(s) Date Subject

d) (2) (3)

Scoping Meeting 10/7/80 Public Discussion of what issues should

be addressed by supplemental EIS.

Public Meeting 7/8/81 Discussion of sludge treatment and dis-

posal alternatives available to City of

Albuquerquemajor emphasis on ex-

planation of irradiation using Cs-137.

21 Citizen Advisory Com- 12/18/80 Study sludge treatment and disposal

mittee Meetings to options and develop recommenda-

12/9/81 tions for preferred alternatives.

Public Hearing 11/18/81 Formal public input and comment on

Draft Supplemental E.I.S.

216

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

disposal available to the City and to recommend a preferred alternative.

As required in the public participation regulations (40 CFR 25.7), the

CAC members were selected by the city to represent four distinct groups

including public officials (elected and appointed), public interest orga-

nizations (health, environmental, social, etc.), economic interests (neigh-

boring land owners, business representatives, etc.) and private citizens.

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

It is worth noting that four members of the committee were engineers.

The CAC was fairly autonomous in that they called and conducted their

own meetings, had use of Water Resource Department staff, and were

able to obtain the services of a number of outside technical advisors in

order to clarify critical issues. Being ad hoc in nature, the committee

disbanded after providing recommendations to the City and EPA.

Throughout the public participation process, the City's irradiation pro-

posal generated intense controversy. Some members of the CAC as well

as the public linked the irradiation technology to nuclear power. Anti-

nuclear advocates strongly opposed irradiation citing threats to environ-

mental safety and health, legitimization of the nuclear energy cycle by

the productive use of waste materials, and the substantial costs associ-

ated with the capital-intensive irradiation facilities in contrast to more

labor-intensive options such as composting. In response, irradiation ad-

vocates including the City's project engineer, representatives from San-

dia Labs, and many members of the CACargued that irradiation was

actually safer and more cost-effective than any other alternative. Not

surprisingly, public meetings were typically long and heated, few in-

stances of genuine compromise occurred, and many participants ex-

pressed dissatisfaction with the performance of others or with the entire

public participation process. The final recommendations of the CAC re-

flect the polarization of the participants; a majority report recommend-

ing irradiation was accompanied by a minority report in opposition to

the irradiation technology. Moreover, the irradiation debate was so per-

vasive throughout the participation process that other components of

the City's proposal were neglected. For example, the CAC was unable

to fully consider the relative costs of sludge transportation alternatives.

The case indicates the clear need for accurate information in the public

participation process. Decision makers and advisory groups should re-

ceive an informed, comprehensive picture of the actual advantages and

disadvantages of the various program options. Unfortunately, inaccurate

and biased information was often the rule rather than the exception in

this case. One source of misinformation came from individuals who did

not understand the technical aspects of the irradiation process. In many

cases their ignorance developed into feelings of mistrust and antago-

nism. A second source of misinformation came from individuals whose

adherence to a narrow, single interest perspective prevented full con-

sideration of other alternatives. Domination of the public meetings by

anti-nuclear activists; for example, contributed to the failure to fully con-

sider economic dimensions of the various options. An obvious but im-

porant solution to the problem of misinformation is the increased par-

ticipation by informed, relatively objective individuals.

Role of the Engineer in the Public Participation Process.Through-

out the public participation process there was extensive involvement by

members of the technical community including physicists, biologists, en-

217

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

vironmentalists, and engineers. Virtually all of the sludge management

options had technical components requiring presentation to, and un-

derstanding by, the CAC. The roles of the engineers involved in the

public participation process are of three basic types as summarized in

Table 2. The three categories are not meant to be mutually exclusive and

it is possible for an individual engineer to assume more than one role

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

even though in the present examples there were no instances of an in-

dividual performing all three roles.

The "bureaucratic engineer" represents an agency of government and

may be a full time staff member or a consultant under contract to the

government agencies involved. Examples from the present study in-

clude staff members of the Water Resources Department, members of

the firm which prepared the Balloon Report, and members of the firm

which contracted with EPA to prepare the EIS. The bureaucratic engi-

neer must effectively explain the problems and available options to the

public, and, most likely, make presentations at a number of different

forums. In addition these engineers may be an important source of in-

formation for the CAC. Consequently, they must have both a thorough

knowledge of the technical components of the proposal and the ability

to present this information to the public and political decision makers.

The credibility of the bureaucratic engineer is enhanced to the extent

TABLE 2.-Summary of Roles of Engineer in Public Participation Programs

Role Description Suggestions for

(1) (2) improving effectiveness

(3)

Bureaucratic a. Public employee with pro- 1. Demonstrate impartiality

Engineer gram responsibility. to project alternatives.

b. Outside engineer employed 2. Demonstrate willingness

by agency having major to work with public.

role in project. 3. Develop credibility by

being objective.

Consultant a. Engineer invited to provide 1. Overcome "hired gun"

Engineer technical information to citi- stereotyping by showing

zen group. concern.

2. Demonstrate independ-

ence from contractor by

considering all

alternatives.

3. Explain technical issues

simply to an often unin-

formed & emotional

public.

4. Develop credibility by

being objective.

Citizen a. Member of Citizen's Advi- 1. Be willing to be critical of

Engineer sory Group. other engineering work.

b. Individual presenting Testi- 2. Help explain technical

mony at public meeting. matters to public.

3. Demand objectivity by all

professional participants.

218

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

that he is perceived by the public to be both technically competent and

uncommitted to a specific alternative. This is especially true when al-

ternatives are controversial as is the use of irradiation. Though he may

have done an extensive analysis of available options and reached a tech-

nically sound conclusion, any apparent lack of objectivity will quickly

result in charges of bias by opponents of the plan or may seriously di-

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

vide the uncommitted public. All presentations should be thoroughly

documented, and when dealing with a relatively small group of the pub-

lic such as the CAC, copies of technical information should be made

available. Moreover, the bureaucratic engineer should provide full and

equal consideration of all alternatives. In our case, the CAC generally

respected and listened to those bureaucratic engineers who demon-

strated both impartiality and competence.

The ''engineering consultant" has the role of providing expert testi-

mony on a limited aspect of the total proposal. In contrast to the bu-

reaucratic engineer who often is intimately involved with the entire pro-

gram, the consultant is called in to satisfy specific needs of the public

participation program. In the present case consultants were utilized to

evaluate the safety of the proposed irradiator design, to complete the

efficiency of sludge disinfection by irradiation and other processes, and

to discuss alternatives to irradiation. In other programs this role might

also include experts retained by special interest groups. In a more lim-

ited public participation program consisting of only a few public hear-

ings it is likely that input from engineering consultants would not be

available to the general public.

Though the engineering consultant must also establish a high degree

of professional credibility with the public, under some circumstances he

may take an advocacy role not allowed the bureaucratic engineer. This

will depend on the type of information that is to be conveyed. In the

present case, an equipment vendor was given the opportunity to present

information on a competing disinfection process. The CAC expected (and

received) a glowing "sales pitch." In another instance, a nuclear engi-

neer was requested to compare the relative merits of gamma and elec-

tron beam irradiation. He therefore was expected by the CAC to be com-

pletely impartial to either alternative. If the consultant is requested to

make an impartial evaluation he must demonstrate as much indepen-

dence from the process as possible.

As noted previously, the CAC members contained a broad spectrum

of technical competence. Consulting engineers therefore must be pre-

pared to address the issues at virtually all levels of technical complexity.

Although the consultant's presentation should be oriented to the general

public, tough, penetrating questions are to be expected. A large amount

of misinformation on the subject may exist and many issues will quickly

become highly emotional. In the present case, for example, agricultural

investigations had been conducted on the effects of feeding irradiated

sludge to farm animals. Consequently, a number of irate citizens made

statements at the public hearings objecting to a purported plan to recycle

the city's human wastes (though somewhat more graphic terms were

generally used) to poorer segments of the community in the form of

meat products.

One obstacle that the engineering consultant must overcome is the

219

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

perception of the consultant as a "hired gun;" one who is brought to

the debate at an outrageous fee to make a brief and disinterested con-

tribution to the process, and then leaves town never to be heard from

again. A respected local engineer is likely to have more credibility with

the public than an out-of-state professional, even one of national

reputation.

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

The third role that the engineer may play in the public participation

process is that of the "citizen engineer." This person has little or no for-

mal involvement in the EIS process as a consultant or bureaucrat, and

becomes active through personal or professional interests or both. In the

present case there were two subcategories, the CAC member engineer

and those engineers who presented testimony at the public hearing.

As noted previously, the current public participation guidelines call

for equal representation between four interest groups: public interests,

private citizens, public officials, and economic interests. The CAC for

this program had at least one engineer from each group except the first.

The CAC member engineer has perhaps a greater opportunity to influ-

ence the EIS process than anyone else except the bureaucratic engineer

in charge of the proposed program. As a member of the CAC, these

engineers will be involved with the process from start to finish. By virtue

of their technical background, they should be able to quickly develop a

thorough understanding of the major issues. Working with the other

members of the CAC over the duration of the project should provide

numerous opportunities to identify points of contention, to public sen-

timent, and to respond in an effective and credible manner.

There are several specific actions the CAC member engineer can take

to increase his effectiveness in the process. The most important is to

maintain an open attitude towards all options. As previously stated, the

perceived bias on the part of "experts" may quickly polarize members

of the public and reduce meaningful communication. The CAC member

engineer should not be reluctant to put other engineers on the spot.

There is a natural reticence to be critical of ones colleagues in a public

forum. However, the committee needs penetrating questions to deter-

mine the veracity of various presentations. If possible, the CAC member

engineer should be willing to perform independent analyses of ques-

tionable material. In the present case, the ability to quickly analyze, sub-

stantiate or refute various findings greatly enhanced the effectiveness of

at least one CAC engineer. His efforts were well received and appreci-

ated by the rest of the committee. The result was that his opinions were

respected and carefully considered when final recommendations were

discussed.

In contrast to the CAC member engineer, the engineer who volunteers

personal opinions at hearings or public meetings probably has the least

amount of influence in the public participation process. In most in-

stances little time is made available for public testimony. Thus, the en-

gineer's credentials cannot be established; it is difficult to elaborate on

many points, and there is little opportunity to review the technical as-

pects of the plan. In addition, testimony by the non-affiliated engineer

is likely to be diluted by the testimony of others, much of which may

be misinformed. These observations are not meant to discourage partic-

ipation at this level but rather to point out some of the constraints which

220

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

should be recognized when preparing ones testimony. Since many peo-

ple have neither the time nor the interest to become more active in most

public participation programs, this option may represent the best op-

portunity to voice ones opinions. More importantly, the informed opin-

ion of the engineer as non-affiliated expert is needed in many public

hearings.

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

Several suggestions can be made which may improve the reception

that testimony provided by a "citizen engineer" receives:

1. First and foremost, avoid issues which present a conflict of interest.

If the engineer represents a firm or process which is reviewed unfavor-

ably in preparing the EIS, do not publicly criticize the EIS under the

guise of involvement as an interested citizen. Someone will quickly and,

most likely, devastatingly point out your affiliation which may seriously

affect your local reputation for professionalism.

2. Do not hesitate to raise obvious questions about items concerning

you. In most public participation programs there is a tremendous amount

of misunderstanding by the public. Questions read into the record at a

public hearing generally must be addressed by staff before the final rec-

ord of decision is made. Presumably the decision makers will review all

public testimony and may ask themselves the same questions.

3. Submit written as well as oral testimony to be certain the points

you wish to communicate are accurately conveyed.

There are many reasons why engineers should become active as citi-

zens in various public participation programs. Engineering training and

practice is based on objectivity. Consequently, engineers should be less

susceptible to persuasion by specious arguments. Moreover, engineers

tend to be more appreciative of the limits of engineering analysis, es-

pecially benefit/cost comparisons. While many engineers are reluctant

to express opinions of matters outside of their particular area of exper-

tise, public participation issues often are not very complicated. Theo-

retically, then, engineers could employ their professional training and

expertise to correct misperceptions and incorrect information often as-

sociated with the public participation process.

Unfortunately, there are a number of reasons why the influence of

engineers is not greater. Traditionally, engineers have restricted their

involvement to professional, rather than public roles. Engineers are often

quite visible as employees of public agencies, as consultants, or as rep-

resentatives of private companies who have an economic interest in the

proposed project. In many cases, the engineer's influence on the public

participation process may be inhibited by professional affiliation. Bu-

reaucratic engineers, for example, may be viewed as "organization men,"

i.e., individuals more concerned with corporate or bureaucratic objec-

tives than with the public interest. Consulting engineers, as discussed,

may be viewed as "hired guns" willing to sell their expertise to the high-

est bidder. The public credibility of these engineers may therefore be

inhibited by stereo types associated with their professional affiliations.

Since the majority of engineers involved in public participation usually

have some such identification, problems associated with public percep-

tions may result. Less obviously, non-affiliated engineers may be reluc-

221

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

tant to participate in public meetings because of potential conflicts of

interests. Finally, many non-affiliated engineers choose not to partici-

pate simply out of apathy; the "silent majority" philosophy. It is un-

fortunate that unless more engineers become involved as citizens in pub-

lic forums, mistrust and misperceptions about technical projects in

particular, and about the engineering profession in general, are likely to

Downloaded from ascelibrary.org by New York University on 05/12/15. Copyright ASCE. For personal use only; all rights reserved.

increase.

Willingness to devote a considerable amount of time without financial

remuneration is of course the key obstacle to all volunteer work. The

benefits to the individual engineer and to the public of an active, civic-

minded engineering community are quite significant. The ability to par-

ticipate is not limited by lack of technical expertise. Objectivity, interest

in the community, and openness are the principal attributes needed.

222

J. Prof. Issues in Engrg. 1983.109:214-222.

You might also like

- EIA Notes U1 PDFDocument11 pagesEIA Notes U1 PDFprashnath100% (1)

- Pre Start-Up / Post Start-Up Check List: Centrifugal PumpsDocument1 pagePre Start-Up / Post Start-Up Check List: Centrifugal PumpsJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Power of Attorney and Declaration of RepresentativeDocument2 pagesPower of Attorney and Declaration of Representativegordon scottNo ratings yet

- Managing Sustainability Assessment of Civil Infrastructure Projects Using Work, Nature, and FlowDocument13 pagesManaging Sustainability Assessment of Civil Infrastructure Projects Using Work, Nature, and FlowStevanus FebriantoNo ratings yet

- Xu2020 Social MEDIADocument14 pagesXu2020 Social MEDIAAna LauricNo ratings yet

- Citizen ParticipationDocument12 pagesCitizen ParticipationAnand SarvesvaranNo ratings yet

- Weaving Ecosystem Services Into Impact AssessmentDocument72 pagesWeaving Ecosystem Services Into Impact AssessmentEstrella PintoNo ratings yet

- Experiences of Voluntary Early Participation in Environmental Impact Assessments in Chilean MiningDocument11 pagesExperiences of Voluntary Early Participation in Environmental Impact Assessments in Chilean Miningluis miguelNo ratings yet

- Report Assg 2 Dia FinalDocument14 pagesReport Assg 2 Dia FinalmyunNo ratings yet

- Poster5 - Biofuelled Energy Plants (EIA) - Case 5Document1 pagePoster5 - Biofuelled Energy Plants (EIA) - Case 5Ajith DNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document3 pagesAssignment 1satpal20253788No ratings yet

- Need For Participatory and Sustainable Principles in India's EIA System: Lessons From The Sethusamudram Ship Channel ProjectDocument13 pagesNeed For Participatory and Sustainable Principles in India's EIA System: Lessons From The Sethusamudram Ship Channel ProjectRakesh SahuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 EIADocument35 pagesChapter 1 EIAfaiselansuarNo ratings yet

- Avaliação Ambiental Estratégica e o Princípio Da Precaução No Planejamento Espacial Dos Parques Eólicos - Experiência Europeia Na SérviaDocument13 pagesAvaliação Ambiental Estratégica e o Princípio Da Precaução No Planejamento Espacial Dos Parques Eólicos - Experiência Europeia Na SérviaEMMANUELLE CARNEIRO DE MESQUITANo ratings yet

- Observing Practice As Participant Observation - Linking Theory To PracticeDocument13 pagesObserving Practice As Participant Observation - Linking Theory To Practiceiam MaxmusNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Compliance To Environmental Impact Assessment and Audit RegulationsDocument12 pagesDeterminants of Compliance To Environmental Impact Assessment and Audit RegulationsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- C $ RRC 2010 11' ,'V FLL 4 ( - "Il"j6Document23 pagesC $ RRC 2010 11' ,'V FLL 4 ( - "Il"j6Tetay MendozaNo ratings yet

- Fasika Asrat A Comparative Study of Factors Affecting The ExternalDocument10 pagesFasika Asrat A Comparative Study of Factors Affecting The ExternalAklilu GirmaNo ratings yet

- Building Leaders of A Global Society: Peter Carrato, P.E., F.ASCEDocument4 pagesBuilding Leaders of A Global Society: Peter Carrato, P.E., F.ASCEAli RajaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) : Overview: Dr. Sanjay MathurDocument57 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment (EIA) : Overview: Dr. Sanjay MathurDebattri DasNo ratings yet

- Basics of EIADocument19 pagesBasics of EIAvivek377No ratings yet

- EIA PaperDocument3 pagesEIA PaperjaciseNo ratings yet

- Sustainability Strategy: Risk and AssumptionsDocument3 pagesSustainability Strategy: Risk and AssumptionsAli SeidNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0197397513000490 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0197397513000490 Main PDFraftar singhNo ratings yet

- SPE 86585 An Integrated Approach To Impact AssessmentDocument6 pagesSPE 86585 An Integrated Approach To Impact Assessmentmohamadi42No ratings yet

- Moon&Bae VEP State Level SNR2011Document17 pagesMoon&Bae VEP State Level SNR2011seong moonNo ratings yet

- 008 - Guidelines For Environmental Impact Assessment 2004-Good-1-50 - Page-0020Document2 pages008 - Guidelines For Environmental Impact Assessment 2004-Good-1-50 - Page-0020andi ilhamNo ratings yet

- Weaving Ecosystem Services Into Impact AssessmentDocument46 pagesWeaving Ecosystem Services Into Impact Assessmentecologiaunadp2010No ratings yet

- Chapter 6 - Environmental Impact Ass.Document34 pagesChapter 6 - Environmental Impact Ass.Inma NchamaNo ratings yet

- Main Reference 4Document8 pagesMain Reference 4CRUSH TYJSNo ratings yet

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) : StructureDocument58 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment (EIA) : StructureMuskan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) : StructureDocument58 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment (EIA) : StructureMuskan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Lecture3 PDFDocument58 pagesLecture3 PDFStephanie MedinaNo ratings yet

- Morgan 2012Document10 pagesMorgan 2012Ryan GinNo ratings yet

- Environmental Impact AssessmentDocument3 pagesEnvironmental Impact AssessmentTarkinNo ratings yet

- Tce Article On Sustainability March 2010Document3 pagesTce Article On Sustainability March 2010Edmar EstacioNo ratings yet

- 10 5923 J MM 20170701 08 PDFDocument22 pages10 5923 J MM 20170701 08 PDFAbraham LebezaNo ratings yet

- Empowering The Public in Environmental Assessment - Advances or Enduring ChallengesDocument8 pagesEmpowering The Public in Environmental Assessment - Advances or Enduring ChallengesBalianiNo ratings yet

- Environmental Impact Assessment - General Procedures: Philip Juma BarasaDocument10 pagesEnvironmental Impact Assessment - General Procedures: Philip Juma BarasaChanelNo ratings yet

- Project Management in Construction: Software Use and Research DirectionsDocument8 pagesProject Management in Construction: Software Use and Research DirectionsMaksim FocusNo ratings yet

- Does Involving Users in Software Development Really Influence System SuccessDocument7 pagesDoes Involving Users in Software Development Really Influence System SuccessGhassan Abu SamhadanaNo ratings yet

- Public Policy and Technology Choices For Municipal Solid Waste Management A Recent Case in LebanonDocument19 pagesPublic Policy and Technology Choices For Municipal Solid Waste Management A Recent Case in LebanonDalemysNo ratings yet

- ADICIONAL Irvin Stansbury Public ParticipationDocument11 pagesADICIONAL Irvin Stansbury Public ParticipationThayanne RiosNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 309 4333 PDFDocument6 pages10 1 1 309 4333 PDFsaaisNo ratings yet

- New ReferencesDocument5 pagesNew Referencesfathyyah21001No ratings yet

- Malaysia EiaDocument11 pagesMalaysia EiaLogesh WaranNo ratings yet

- Public Awareness and The Environment "How Do We Encourage Environmentally Responsible Behaviour"Document8 pagesPublic Awareness and The Environment "How Do We Encourage Environmentally Responsible Behaviour"SITI NUR NADIA AHMAD SHUKRINo ratings yet

- Measuring Progress of Waste Management ProgramsDocument6 pagesMeasuring Progress of Waste Management ProgramsArmikurnia SavitriNo ratings yet

- CHP 1Document16 pagesCHP 1Divya ShahNo ratings yet

- DENR AO On EIA Public ParticipationDocument21 pagesDENR AO On EIA Public ParticipationSam Sy-HenaresNo ratings yet

- EIA Assessment in MalaysiaDocument5 pagesEIA Assessment in MalaysiaSultan DwierNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To The Concept of Environmental Audit: Indian ContextDocument8 pagesAn Introduction To The Concept of Environmental Audit: Indian ContextAbhi VishwakarmaNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Civil Engineering Infrastructures in The Sustainability of The EnvironmentDocument12 pagesImpacts of Civil Engineering Infrastructures in The Sustainability of The Environmentandang ikhsanNo ratings yet

- A Causal Network Approach Using A Community Well Being F - 2023 - EnvironmentalDocument12 pagesA Causal Network Approach Using A Community Well Being F - 2023 - EnvironmentalJoaquín Andrés MaturanaNo ratings yet

- Contextual Attributes Associated With Public Participation in Enviro - 2023 - HeDocument13 pagesContextual Attributes Associated With Public Participation in Enviro - 2023 - HeAnurag PawarNo ratings yet

- Interference Management Techniques in Cellular Networks: A ReviewDocument11 pagesInterference Management Techniques in Cellular Networks: A ReviewHashimNo ratings yet

- P-Environmental Impact Assessment For Building Construction ProjectsDocument12 pagesP-Environmental Impact Assessment For Building Construction ProjectsFitri WulandariNo ratings yet

- The Social and Environmental Impact Assessment Process: A Guide To Biodiversity For The Private SectorDocument3 pagesThe Social and Environmental Impact Assessment Process: A Guide To Biodiversity For The Private SectorxuealietteNo ratings yet

- Increasing Project Flexibility: The Response Capacity of Complex ProjectsFrom EverandIncreasing Project Flexibility: The Response Capacity of Complex ProjectsNo ratings yet

- The Social Inclusion: Theoretical Development and Cross-cultural MeasurementsFrom EverandThe Social Inclusion: Theoretical Development and Cross-cultural MeasurementsPeter J. HuxleyNo ratings yet

- New sanitation techniques in the development cooperation: An economical reflectionFrom EverandNew sanitation techniques in the development cooperation: An economical reflectionNo ratings yet

- Gross Pollutant Traps to Enhance Water Quality in MalaysiaFrom EverandGross Pollutant Traps to Enhance Water Quality in MalaysiaNo ratings yet

- Junaid Ahmad: Personal Skills ObjectiveDocument1 pageJunaid Ahmad: Personal Skills ObjectiveJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Danial Ali Raza: Ersonal NformationDocument3 pagesDanial Ali Raza: Ersonal NformationJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Residence or Bed SpaceDocument2 pagesResidence or Bed SpaceJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Junaid CV Call CenterDocument1 pageJunaid CV Call CenterJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Junaid Ahmad: Personal Skills ObjectiveDocument1 pageJunaid Ahmad: Personal Skills ObjectiveJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- CV, Junaid AhmadDocument1 pageCV, Junaid AhmadJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Junaid Ahmad: Rupali Polyester, SheikhupuraDocument1 pageJunaid Ahmad: Rupali Polyester, SheikhupuraJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Application Form: Federal Punjab KPK SindhDocument3 pagesApplication Form: Federal Punjab KPK SindhJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Armed Force Test Preparation ResourceDocument7 pagesArmed Force Test Preparation ResourceJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Form PEC-TL (Final)Document3 pagesForm PEC-TL (Final)Junaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Impact of Computer Use On ChildrenDocument1 pageImpact of Computer Use On ChildrenJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- 100 Instructions by Allah in QuranDocument3 pages100 Instructions by Allah in QuranJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- BrochureDocument2 pagesBrochureJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Project Goals:: Note That This Is Not Included in The Workbook YetDocument3 pagesProject Goals:: Note That This Is Not Included in The Workbook YetJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Computer Eye StrainDocument9 pagesComputer Eye StrainJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- How To Find and ContactDocument4 pagesHow To Find and ContactJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Chemie Ingenieur Technik Volume 73 Issue 6 2001 (Doi 10.1002/1522-2640 (200106) 73:6-696::aid-Cite6962222-3.0.Co;2-t) Th. Rieckmann; S. VöLker - Product Quality of Recycled Food GradeDocument1 pageChemie Ingenieur Technik Volume 73 Issue 6 2001 (Doi 10.1002/1522-2640 (200106) 73:6-696::aid-Cite6962222-3.0.Co;2-t) Th. Rieckmann; S. VöLker - Product Quality of Recycled Food GradeJunaid AhmadNo ratings yet

- Finance Act 2010Document5 pagesFinance Act 2010Tapia MelvinNo ratings yet

- Advertisement20190403 163037Document19 pagesAdvertisement20190403 163037maneeshnithNo ratings yet

- How To Interpret A Motor Vehicle Search Result and Search Certificate PDFDocument2 pagesHow To Interpret A Motor Vehicle Search Result and Search Certificate PDFVasif SholaNo ratings yet

- 1BC - AMMONIUM BISULFATE (NH4HSO4) - SDS-US - EnglishDocument6 pages1BC - AMMONIUM BISULFATE (NH4HSO4) - SDS-US - EnglishAkhmad MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Armstrong 2016 Commentary Uk Housing Market Problems and PoliciesDocument5 pagesArmstrong 2016 Commentary Uk Housing Market Problems and PoliciesCandelaNo ratings yet

- NRSAP 2021-30 Draft Final 14apr22 1658832893Document159 pagesNRSAP 2021-30 Draft Final 14apr22 1658832893black webNo ratings yet

- Promotion Study Material - 2016Document281 pagesPromotion Study Material - 2016Aditya Maheshwari100% (3)

- Admin Law Project FinalDocument26 pagesAdmin Law Project FinalAnurag PrasharNo ratings yet

- PRO-HSE 001 HSE Objective and Management System Rev.0ADocument6 pagesPRO-HSE 001 HSE Objective and Management System Rev.0ADesfrial DialNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Agreement: (Host Company/Institution and Student Intern Re: Internship)Document6 pagesMemorandum of Agreement: (Host Company/Institution and Student Intern Re: Internship)Aira AmorosoNo ratings yet

- Ex Post Facto LawDocument11 pagesEx Post Facto LawPatrick James Tan100% (2)

- PNHS Main Const. and by Laws 2022Document5 pagesPNHS Main Const. and by Laws 2022angieNo ratings yet

- Chemviron Clarcel CBLDocument13 pagesChemviron Clarcel CBLCardoso MalacaoNo ratings yet

- Appointment Letter - Nikhil KhedekarDocument3 pagesAppointment Letter - Nikhil KhedekarGajendra PatilNo ratings yet

- University of Moratuwa Faculty of EngineeringDocument5 pagesUniversity of Moratuwa Faculty of EngineeringChiranjaya HulangamuwaNo ratings yet

- BIGBLOC - Dealer KYC FormDocument2 pagesBIGBLOC - Dealer KYC FormSuresh NXTNo ratings yet

- 3c Case Study IDEKO Workbook - CASE STUDYDocument8 pages3c Case Study IDEKO Workbook - CASE STUDYTiffany SandjongNo ratings yet

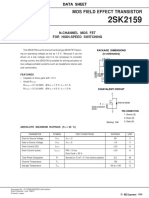

- 2SK2159Document6 pages2SK2159hectorsevillaNo ratings yet

- Automated Entry-Exit System With SmsDocument8 pagesAutomated Entry-Exit System With SmsenzoNo ratings yet

- The Robber BridegroomDocument4 pagesThe Robber BridegroomKuberNo ratings yet

- UK Visas & Immigration: Personal InformationDocument3 pagesUK Visas & Immigration: Personal InformationАлександрNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER II. CICM in The WorldDocument9 pagesCHAPTER II. CICM in The WorldJocelyn TabudlongNo ratings yet

- CertificateDocument4 pagesCertificateshubh cards bhilwara Wedding cardsNo ratings yet

- Company Law SummaryDocument48 pagesCompany Law SummaryKaustubh BasuNo ratings yet

- RicaldeDocument2 pagesRicaldeIan ManglicmotNo ratings yet

- Dreamland Resort Case StudyDocument33 pagesDreamland Resort Case StudyChristine joy GacadNo ratings yet

- PadoraDocument3 pagesPadoraTan JunNo ratings yet

- Teodorico Miranda Vs Asian Terminals Inc.Document2 pagesTeodorico Miranda Vs Asian Terminals Inc.Therese PalilloNo ratings yet

- Talend DataIntegration IG Windows 6.4.1 ENDocument122 pagesTalend DataIntegration IG Windows 6.4.1 ENBhanu PrasadNo ratings yet