Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cpla PDF

Uploaded by

Jasmin BaruzoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cpla PDF

Uploaded by

Jasmin BaruzoCopyright:

Available Formats

CHAPTER 17

Cordillera Peoples Liberation Army (CPLA)

Overview

The Cordillera Peoples Liberation Army (CPLA) is an armed group of indig-

enous people in the Cordillera mountain range of northern Luzon, many

members of which have been integrated into the Armed Forces of the Philip-

pines (AFP). Originally made up of units that split from the Communist Party

of the Philippines-New Peoples Army (CPP-NPA), it has since suffered from

factionalism and inghting. It continues to push for regional autonomy, more

than 20 years after signing a peace pact with the Philippine government.

Basic characteristics

Typology

The CPLA is an armed group of indigenous people based in the Cordillera

mountains that seeks regional autonomy and is currently being integrated

into the government armed forces. The group now considers armed struggle

to be secondary to legal parliamentary struggle (Buendia, 1991).

Current status

There are conicting reports about the status of the CPLA. The group was

rst reportedly unied under the leadership of Mailed Molina and Corazon

Cortel (Conrado Balwegs widow, see below) with Arsenio Humiding acting

as chair when Molina ran for a government position (Cabreza, 2007). Molina

was still claiming the chairmanship in 2008.1 According to the Ofce of the

Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process (OPAPP), the CPLA has divided

into at least three factions. Once applauded for helping with peacekeeping in

the region, some CPLA elements and factions have been accused of murder,

illegal logging, and marijuana trafcking (CRC, 1989). Hundreds of CPLA

318 Primed and Purposeful

members were integrated into the Philippine Army (AFP) and Citizens Armed

Force Geographical Unit (CAFGU) militia in 2001 (see Chapter 6).

Origin

In the early 1970s, indigenous people joined the New Peoples Army (NPA)

and the Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) in resisting the Marcos dictator-

ship and the operations of multinational companies in the Cordillera, in par-

ticular the Cellophil Resources Corporation in Abra, the Chico River Dam

project spanning the Mountain Province and Kalinga, and the Batong Buhay

Gold Mining Project in Kalinga. The Cordillera mountain ranges soon became

known as active operations bases for the NPA (CRC, 2000, p. 1). The Cordillera

units seceded from the NPA because of perceived discrimination against high-

land NPA members; by the drive by ex-Catholic priest turned NPA commander

Conrado Balweg for the self-determination of mountain tribes to be recognized

immediately and not only after victory; and by the decision by the NPA to

put Balweg under house arrest on suspicion of sexual and nancial oppor-

tunism (Coronel-Ferrer, 1997, pp. 21314; CRC, 2000, p. 1). They established

the CPLA in April 1986soon after the fall of the Marcos dictatorshipand

focused on the struggle for regional autonomy and self-determination. The

founding members were mostly Cordillerans belonging to different ethno-

linguistic national minorities.

In September 1986, the CPLA entered into a sipat (cessation of hostilities)

with President Corazon Aquino. It became a partner of the government for

development projects in the Cordilleras, though it continued to agitate against

the Cellophil Resources Corporation and the Chico River Dam project. The

group continued to advocate regional autonomy, which was only partially

granted by the governments of Aquino and her successors, Fidel Ramos, Joseph

Estrada, and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (see Chapter 6).

Internally, the CPLA faced a leadership problem and accused Balweg of mis-

use of the organizations funds, corruption, and dereliction of duties as leader

(CPLA, 1993). On 30 June 1993 the CPLA and its political arm, the Cordillera

Bodong Administration (CBA), announced a reshufe, which Balweg rejected,

leading to the creation of another CPLA faction headed by Mailed Molina and

James Sawatang. The government sided with Balweg. The NPA killed Balweg

Part Two Armed Group Proles 319

in Abra in 1999 (Rousset, 2003), whereupon his widow Corazon Cortel took

over the CPLA leadership. Cortel eventually joined Molina;2 she died of natu-

ral causes in March 2008. The government, through the OPAPP, continues to

deal with this faction (OPAPP, 2008).

The group has suffered politically and economically in recent years, and

has expressed anger at the failure of successive governments to honour their

commitments to grant the region greater autonomy and to integrate CPLA

members into the AFP and the ofcial auxiliary groups of the security forces.

In 2001, President Arroyo signed an order integrating 264 Mailed-faction

members into the AFP and 528 members into six CAFGU companies deployed

in six Cordillera provinces and elsewhere (OPAPP, 2008; Solmerin, 2004). In

2004, the CBA and the CPLA again declared autonomy and threatened war.

In April 2008, a new agreement was signed promising to full the commitments

of the 1986 Mount Data Peace Accord.

Aims and ideology

The core CPLA demand was the setting up of a Cordillera autonomous re-

gion founded on the indigenous peace pact institution of the bodong, which

results in alliances and commonwealths of tribes. The CPLA and the CBA do

not wish to secede from the national government, but aim to free their indig-

enous people from the Filipino majority that makes use of the State to per-

petuate national oppression against the minority people in the Cordillera

(Garming, 1989, p. 9). They seek autonomy, equal rights, justice against oppres-

sion and exploitation, and participation in peacekeeping in their territories.

Formerly with the CPP-NPA, the CPLA has since eschewed Marxism-Leninism-

Maoism, aiming instead for Cordillera regional autonomy through parliamentary

struggle based on the bodong.

Leadership

Arsenio Humiding is acting leader of the unied CPLA. Former chair Mailed

Molinathe former mayor of Bucloc town who was briey arrested in June

2007 on charges of drug trafcking and possession of illegal weaponscon-

tinues to describe himself as CPLA chair (Andrade, 2007; Cabreza, 2007). As

of 200304, at least three other CPLA factions exist: the Yao group, the Bun-as

320 Primed and Purposeful

group, and the Aydinan group of the CPLA-Kalinga (OPAPP, 2008). When

interviewed in Cagayan de Oro City on 30 November 2006, Corazon Cortel

and Arsenio Humiding of the unied CPLA dismissed them as leftovers

rather than factions. The Balweg and the Molina factions united under their

newly elected chairman Mailed Molina at a Workshop on CPLA Concerns

held on 25 April 2008 in Tabuk City, Kalinga province. The April 2008 Joint

Declaration of Commitment promising to full the commitments of the 1986

Mount Data Peace Accord with the GRP was signed on the CPLAs behalf by

Molina and CBA President Marcelina Bahatan.

Political base, combatants, and constituency

The various CPLA factions claim the same mass base, eld commanders, and

foot soldiers among the indigenous people in the central Cordillera region.

This region comprises the provinces of Abra, Apayao, Benguet, Ifugao, Kalinga,

and Mountain Province (CPA, n.d., p. 7). The Cordillera Bodong Administra-

tion led by Marcelina Bahatan is the CPLAs political centre (Cabreza, 2007).

Sources of nancing and support

The government released PHP 10 million (USD 380,400) in livelihood loan

assistance to former rebels in 198696 and PHP 7.5 million (USD 285,300) for

development projects in the Cordillera (Coronel-Ferrer, 1997).3 Twenty years

after the peace pact, the government admitted it had not delivered on its

promises of land reform, integration, or even clean water, good roads, and

livelihood projects for the Kalinga CPLA (Cabreza, 2006a, p. A20). The Phil-

ippine Senate cut the 2006 budget allocation for development projects in the

Cordilleras (Cabreza, 2006b).

Military activities

Size and strength

In 2001, around 1,200 CPLA members were integrated into the AFP and prom-

ised livelihood projects by the government. In 2006, President Arroyo directed

the Department of National Defense to integrate 3,800 CPLA members into

the ofcial security forces and the armed civilian auxiliary forces (see Chap-

Part Two Armed Group Proles 321

ter 6). The government estimated active CPLA members to number 4,000 in

2007 (PIA, 2007).

Collaboration and friction with other armed groups

The CPLA engages in sporadic ghting with NPA units in the Cordilleras. In

2004, the CPLA urged all non-Cordillera armed groupsincluding the AFP,

the NPA, and private armiesto leave their territory (Solmerin, 2004).

In 1999, the Mailed CPLA faction forged an alliance with the Sosyalitang

Partido ng Paggawa (SPP), which is reportedly made up of breakaway organi-

zations and personalities from the local Communist movements with links to

the MNLF, the MILF, and the Abu Sayyaf Group (Benguet Police Provincial

Ofce, 2000). The SPP eventually merged with the Filipino Workers Party

(Partido ng Manggagawang Pilipino, PMP) in 2002 (see Chapter 14).

Small arms and light weapons

Guns are highly valued among the people in the Cordilleras and nearby prov-

inces. CPLA members and their sympathizers have not laid down arms, and

argue that the peace pact between the government and the CPLA does not

require them to do so.

Spears, bolos, and other primitive weapons have traditionally been used by

Cordillera indigenous people in warfare but have been supplanted in many

instances by guns, which have reportedly altered the nature of ritual peace

processes among politically autonomous villages engaged in conict over

water rights, boundary disputes, or killings and counter-killings. Previously

a declaration of war accompanied by rituals and omens used to precede hos-

tilities in traditional warfare. In addition, peace sanctuary areas were main-

tained, and combat was face-to-face. Such rituals are reportedly no longer

followed because bullets made reprisals too impersonal (Prill-Brett, 2005).

Human security issues

Children associated with ghting forces

A 2005 independent report suggests child soldiers were recruited (PHRIC, 2005).

322 Primed and Purposeful

Human rights

The CPLA has been accused of human rights abuses, including the killing of

CPP sympathizer and tribal leader Daniel Ngayaan in 1987 and harassment

of an NGO conducting relief operations for earthquake victims that same

year. Molina has been accused of continuing to recruit peoplesome with

criminal recordsto his private army and of using his private army to his

personal political advantage; he rejects the accusations. In 1999, the Baguio

City Council proclaimed Molina persona non grata after he paraded in the city

with 300 armed men on Cordillera day (Benguet Police Provincial Ofce, 2000;

CPA, c. 1988).

Outlook

More than 20 years after signing a peace pact with the government in 1986,

the CPLA has not realized its goal of helping to develop the tribal communi-

ties of the Cordillera, much less achieved the autonomy it aspires to (Malanes,

2007). The Cordillera peace pactthe rst peace agreement between the Phil-

ippine government and a rebel groupmay be an example of a failed experi-

ence in disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) if it is not saved

by the present government. The GRP and the CBA-CPLA signed a Joint Dec-

laration of Commitment on 25 April 2008 toward the completion of the 1986

Mount Data Peace Accord. Consensus points included an expansion of liveli-

hood assistance to CPLA members who have not beneted in the past and

the involvement of the Department of Justice to determine the correct inter-

pretation of the provision for the establishment of the Cordillera Regional

Security Force (see Chapter 6).

Endnotes

1 A news report from 8 November 2009 suggests that Molina was voted out of the leadership

(Madarang, 2009).

2 Interview with Corazon Cortel, 30 November 2006.

3 Currency conversions at the rate obtaining on 31 December 1996.

Part Two Armed Group Proles 323

Bibliography

Albano, Estanislao, Jr. 2004. CPLA Revokes Peace Accord with Natl Govt: Hits Insincerity in

Implementing Pact. Manila Bulletin. 8 September.

<http://www.mb.com.ph/PROV2004090918076.html>

Andrade, Jeannette I. 2007. Abra Mayors Arrest Kept Secret. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Manila).

20 June, p. A23.

Benguet Police Provincial Ofce. 2000. Special Report re Recruitment of CPLA at Mankayan,

Benguet. 7 June.

Buendia, Rizal. 1991. The Cordillera Autonomy and the Quest for Nation-Building: Prospects in

the Philippines. Philippine Journal of Public Administration, Vol. 35, No. 4. October, pp. 33568.

Cabreza, Vincent. 2005. Guns Alter Tribal Peace Process. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Manila).

21 December, p. A15.

_____. 2006a. Govt Reviews Peace Pact with Balweg Militia. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Manila).

8 May, p. A20.

_____. 2006b. Beneciaries of Palace Pork Lobby to Keep Funds. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Manila).

6 June, p. A14.

_____. 2007. CPLA Heads Arrest Leads to Restudy of 87 Pact. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Manila).

19 June, p. A15.

Cordillera Bodong Administration, Cordillera Peoples Liberation Army, and Montanosa National

Solidarity. 1989. Towards the Solution of the Cordillera Problem: Statement of Position. Pre-

sented to President Corazon C. Aquino during the Cordillera Peace Talk held on 13 September

1986 at Mt. Data Lodge, Bauko, Mountain Province. In Edmundo Garcia and Carolina G.

Hernandez, eds. Waging Peace in the Philippines: Proceedings of the 1988 International Conference

on Conict Resolution. Quezon Ciy: Ateneo Center for Social Policy and Public Affairs and

University of the Philippines Center for Integrative and Development Studies.

Coronel-Ferrer, Miriam, ed. 1997. Peace Matters: A Philippine Peace Compendium. Manila: University

of the Philippines.

CPA (Cordillera Peoples Alliance). c. 1988. Ensure the Victory of Genuine Autonomy.

<http://cwis.org/fwdp/Eurasia/cpa-stat.txt>

CPAEducation Commission and Regional Ecumenical Council in the Cordillera. n.d. A Consolidated

Study Guide on the National Minorities in the Cordillera. Baguio City.

CPLA (Cordillera Peoples Liberation Army). 1993. CPLA Declaration of Positions. July.

CRC (Cordillera Resource Center). 1989. What is Genuine Regional Autonomy? Cordillera Papers

Monograph No. 1. Baguio City.

_____. 2000. CPLA Integration: Final Coordination Meeting on CPLA Integration. 18 August.

Garming, Maximo B. 1989. Towards Understanding the Cordillera Autonomous Region. Manila: Friedrich

Ebert-Stiftung. 22 November.

Madarang, Larry. 2009. CPLA Leaders Oust Molina; Elect Humiding Chairman. Northern Phil-

ippine Times (La Trinidad). 8 November. <http://northphiltimes.blogspot.com/2009/11/cpla-

leaders-oust-molina-elect-humiding.html>

Malanes, Maurice. 2007. Elusive Cordillera Autonomy. Philippine Daily Inquirer (Manila). 19 Sep-

tember, p. A19.

324 Primed and Purposeful

OPAPP (Ofce of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process). 2008. Update on the CPLA,

24 October 2007. <http://www.opapp.gov.ph/index.php?option=com_content&task=blog

category&id=27&Itemid=111>

Philippine Daily Inquirer (Manila). 1996. Cordillerans 97 wish: Autonomy. 31 December, p. 14.

. 1997. Cordillera Folk Reject Autonomy. 10 March, p. 17.

PHRIC (Philippine Human Rights Information Center). 2005. Deadly Playgrounds: The Phenomenon

of Child Soldiers in the Philippines. Quezon City: PHRIC.

PIA (Philippine Information Agency). 2007. OPAPP Heads Task Force for CPLA Concerns. Press

Release 2007/09/22. <http://www.pia.gov.ph/?m=12&=p070922.htm&no=7>

Prill-Brett, June. 2005. Tribal War, Customary Law and Legal Pluralism in the Cordillera, North-

ern Philippines. Professorial Chair Lecture, University of the Philippines Baguio. December.

Rousset, Pierre. 2003. After Kintanar, the Killings Continue: The Post-1992 CPP Assassination Policy

in the Philippines. 3 July. <http://www.philsol.nl/A03b/CPPAssPol-Rousset-jul03.htm>

Solmerin, Florante. 2004. Cordillerans Declare Autonomy, CPLA Prepares for War vs. Govt Anew.

Manila Times. 16 September. <http://www.abrenian.com/modules/newbb/print.php?form=

1&topic_id=3&forum=2&order=ASC&start=640>

Sun Star Baguio. 2008. CPLA Faction Denies Offering Aid to Wal family. 7 February.

<http://www.sunstar.com.ph/static/bag/2008/02/07/news/cpla.faction.denies.offering.

aid.to.wal.family.html>

Part Two Armed Group Proles 325

You might also like

- DumalanDocument1 pageDumalanJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- DesignationDocument1 pageDesignationJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- DesignationDocument1 pageDesignationJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Hazel Clare B. Sangdaan Ins201 Pauline EthicsDocument2 pagesHazel Clare B. Sangdaan Ins201 Pauline EthicsJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Philippine province reassigns driver to new office dutiesDocument1 pagePhilippine province reassigns driver to new office dutiesJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Tattoo PDFDocument85 pagesTattoo PDFJasmin Baruzo100% (1)

- BawalanDocument1 pageBawalanJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Philippine official details staff to local barangayDocument2 pagesPhilippine official details staff to local barangayJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- BenzonDocument2 pagesBenzonJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- DumalanDocument1 pageDumalanJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- ActivityDocument2 pagesActivityJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Cordillera Administrative Region Philippines Vice-Governor Office ReassignmentDocument2 pagesCordillera Administrative Region Philippines Vice-Governor Office ReassignmentJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- B9 D 01Document47 pagesB9 D 01uktaindraNo ratings yet

- Brokering Peace Among Tribes PDFDocument8 pagesBrokering Peace Among Tribes PDFJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Civil Service Commission Memorandum Circular No. 19, S. 1992 - Creation of New Positions Offices PDFDocument10 pagesCivil Service Commission Memorandum Circular No. 19, S. 1992 - Creation of New Positions Offices PDFDael GerongNo ratings yet

- Day1 PM Panel3 4philippines (Tabuk) Lammawin PDFDocument11 pagesDay1 PM Panel3 4philippines (Tabuk) Lammawin PDFJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Charateristics of The Bride of ChristDocument13 pagesCharateristics of The Bride of ChristJasmin Baruzo100% (1)

- RR 1-2015 - de Minimis BenefitsDocument1 pageRR 1-2015 - de Minimis BenefitsKeir TurlaNo ratings yet

- Bride 5 PDFDocument14 pagesBride 5 PDFJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Award PNP PDFDocument2 pagesAward PNP PDFJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- GuideSigningandWitnessingaDocumentProcedureManual PDFDocument33 pagesGuideSigningandWitnessingaDocumentProcedureManual PDFJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- Agri-Tourism - Farm Site PDFDocument10 pagesAgri-Tourism - Farm Site PDFClaris CaintoNo ratings yet

- DILG Legal - Opinions 2011314 079aa90c91 PDFDocument2 pagesDILG Legal - Opinions 2011314 079aa90c91 PDFJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- 0e2613939 - 1383592819 - Growing 200 Identity Gender w4 Summary Identity in Christ Handout PDFDocument2 pages0e2613939 - 1383592819 - Growing 200 Identity Gender w4 Summary Identity in Christ Handout PDFJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

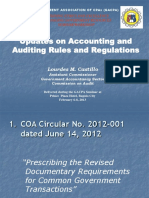

- GACPA Seminar Updates Accounting RulesDocument72 pagesGACPA Seminar Updates Accounting RulesJasmin Baruzo100% (1)

- Taxation Law Q&A 1994-2006 PDFDocument73 pagesTaxation Law Q&A 1994-2006 PDFClark LimNo ratings yet

- Installation Service For RevDocument2 pagesInstallation Service For RevJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- 2014 OctoberDocument131 pages2014 OctoberJasmin BaruzoNo ratings yet

- UST GN 2011 - Civil Law ProperDocument549 pagesUST GN 2011 - Civil Law ProperGhost100% (5)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- TicketDocument2 pagesTicketbikram kumarNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Presentment For AcceptanceDocument27 pagesAcceptance and Presentment For AcceptanceAndrei ArkovNo ratings yet

- Lecture7 PDFDocument5 pagesLecture7 PDFrashidNo ratings yet

- Superior University: 5Mwp Solar Power Plant ProjectDocument3 pagesSuperior University: 5Mwp Solar Power Plant ProjectdaniyalNo ratings yet

- Perbandingan Sistem Pemerintahan Dalam Hal Pemilihan Kepala Negara Di Indonesia Dan SingapuraDocument9 pagesPerbandingan Sistem Pemerintahan Dalam Hal Pemilihan Kepala Negara Di Indonesia Dan SingapuraRendy SuryaNo ratings yet

- RCA - Mechanical - Seal - 1684971197 2Document20 pagesRCA - Mechanical - Seal - 1684971197 2HungphamphiNo ratings yet

- Road Safety GOs & CircularsDocument39 pagesRoad Safety GOs & CircularsVizag Roads100% (1)

- Lesson 3 - Materials That Undergo DecayDocument14 pagesLesson 3 - Materials That Undergo DecayFUMIKO SOPHIA67% (6)

- QDA Miner 3.2 (With WordStat & Simstat)Document6 pagesQDA Miner 3.2 (With WordStat & Simstat)ztanga7@yahoo.comNo ratings yet

- 13 Daftar PustakaDocument2 pages13 Daftar PustakaDjauhari NoorNo ratings yet

- FC Bayern Munich Marketing PlanDocument12 pagesFC Bayern Munich Marketing PlanMateo Herrera VanegasNo ratings yet

- De Thi Thu THPT Quoc Gia Mon Tieng Anh Truong THPT Hai An Hai Phong Nam 2015Document10 pagesDe Thi Thu THPT Quoc Gia Mon Tieng Anh Truong THPT Hai An Hai Phong Nam 2015nguyen ngaNo ratings yet

- Market Participants in Securities MarketDocument11 pagesMarket Participants in Securities MarketSandra PhilipNo ratings yet

- Cagayan Electric Company v. CIRDocument2 pagesCagayan Electric Company v. CIRCocoyPangilinanNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae 2010Document11 pagesCurriculum Vitae 2010ajombileNo ratings yet

- University Assignment Report CT7098Document16 pagesUniversity Assignment Report CT7098Shakeel ShahidNo ratings yet

- Data SheetDocument14 pagesData SheetAnonymous R8ZXABkNo ratings yet

- Programming in Java Assignment 8: NPTEL Online Certification Courses Indian Institute of Technology KharagpurDocument4 pagesProgramming in Java Assignment 8: NPTEL Online Certification Courses Indian Institute of Technology KharagpurPawan NaniNo ratings yet

- Feb 22-Additional CasesDocument27 pagesFeb 22-Additional CasesYodh Jamin OngNo ratings yet

- James Ashmore - Curriculum VitaeDocument2 pagesJames Ashmore - Curriculum VitaeJames AshmoreNo ratings yet

- ViscosimetroDocument7 pagesViscosimetroAndres FernándezNo ratings yet

- DX133 DX Zero Hair HRL Regular 200 ML SDS 16.04.2018 2023Document6 pagesDX133 DX Zero Hair HRL Regular 200 ML SDS 16.04.2018 2023Welissa ChicanequissoNo ratings yet

- Why Companies Choose Corporate Bonds Over Bank LoansDocument31 pagesWhy Companies Choose Corporate Bonds Over Bank Loansতোফায়েল আহমেদNo ratings yet

- ProkonDocument57 pagesProkonSelvasatha0% (1)

- CCTV8 PDFDocument2 pagesCCTV8 PDFFelix John NuevaNo ratings yet

- PB Engine Kappa EngDocument20 pagesPB Engine Kappa EngOscar AraqueNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management NotesDocument115 pagesMarketing Management NotesKajwangs DanNo ratings yet

- High Uric CidDocument3 pagesHigh Uric Cidsarup007No ratings yet

- A. Readings/ Discussions Health and Safety Procedures in Wellness MassageDocument5 pagesA. Readings/ Discussions Health and Safety Procedures in Wellness MassageGrace CaluzaNo ratings yet

- Lirik and Chord LaguDocument5 pagesLirik and Chord LaguRyan D'Stranger UchihaNo ratings yet