Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Skillie

Skillie

Uploaded by

Irma Ketchup0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views309 pagesEl Gazali Ihja ulum ed-din

Original Title

skillie

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentEl Gazali Ihja ulum ed-din

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views309 pagesSkillie

Skillie

Uploaded by

Irma KetchupEl Gazali Ihja ulum ed-din

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 309

77-32, 719

SKELLIE, Walter James, 1899-

THE RELIGIOUS PSYCHOLOGY OF AL-GHAZZALi:

‘A TRANSLATION OF HIS BOOK OF THE IHYA’ oN

THE EXPLANATION OF THE MONDERS OF SHE HEART

WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES.

The Hartford Seminary Foundation, Ph.D., 1938

Religion, history

University Microfilms International , sn rvor. Michigan 48106

© = 1977

WALTER JAMES SKELLIE

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

‘THE RELIGIOUS PSYCHOLOGY OF AL-GHAZZALT

A Translation of His Book of the IEYA? on

THE EXPLANATION OF THE WONDERS OF THE KEART

with Introduction and Notes

Submitted 2 the Faculty

of the

KENNEDY SCHOOL OF MISSIONS

HARTFORD SSMINARY FOUNDATION

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOFRY

Walter James Skellie

April 1938

vim.

alter Jemes Skellie wes born in Argyle, New York, on

Dec. 20, 1899, the son of Archibald cow and Elizabeth Fersha

Skellie. He attended country school, end gradueted from argyle

High School in 1916, is college was westminster Collegs, Nev

‘Filmington, Pa., where he graduated vith honor in 1921.

on

tered Pittsburgh Theological Seminary thet fell and received the

degree of Th. 3. with honor in 1924 and was awarded the Jamieson

Scholarship for thet yaar,

In the Church in which he had been reared he wes ordained

to the ministry of the Gospel for foreign wissionary

rrice by

the Argyle Presbytery of ths United Presbyterien Church in ley 1924.

jo has served the Sgyptian uission under the Board of Foreign

Missions of that Church from October 1924 until the present tine.

From 1924 until 1926 he was located in Cairo for language study,

and then he was sent to Alexandria to assist in the work of that

city and district.

His first furlough in America was spent at the Kennedy

School of Wiseions in Hartford, where he received the Hed. degrea

in Islamics in 1930.

Returning to igypt in September 1930 ne wes located in

Luxor for evangelistic work in thet district, with supervision of

some schools in the district. This service has been rendered in

close cooperation with the Sgyptian Zvangelicel Church.

In 1931 he registered with the Kennedy School of

Missions for advanced study, end has been working on this book

of al-Ghazzli's end releted subjects since thet time. Re

spent the school yeer 1937 - 38 in res:

nce in Hertford for

the completion of this work.

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

Table of Contents. . . . . 1 es ee page fe

Intreduction, 2 6. 6 ew

Ae A Biographical Sketch of Al-Ghazz€1i. . . 444,

Be A Sketch of al-chazz@li's Psychology

C. Texts Used in Translation. ... . . . itd,

D. A Summary of the Translation. . . . . liv,

Translation. . . .

Introductions 6 6 1 eee ee ae le

Chapter I. The Weaning of

rt', ‘Spirit!

*Soul' and 'Intelligenc oe 5S

Chapter II, The armies of the Heart. . . 13.

Chapter ITI, The Similitudes of the Heart

vith its Internal armies. . . 19.

Chapter IV, The Special Froperties of the

art of Man. 2 2 2 ee ew 25.

Chapter V, ‘The Cualities and Similitudes of

the Heart. 6 ee ee ee 366

Chapter VI. ‘The Heart as Related to the

Special Sciences. « » s + + 46.

Chapter VII. ‘The Heart as Related to the

Divisions of the Sciences. . + « 61.

Chapter VIII. ‘The Difference between the Wy

of the iff and thet of the Specu-

lative Philosophers... . + + 70.

Chapter IX, A Tangible Example of the Differ=

ence in Rank of the Two Positions . . 78+

ike

Chapter X, The Validity of the Zxperiential

Knowledge of the uystic. . . . . . 906

Chapter XI, Satan's Domination over the Heart

through Evil Promptings. . » . . 102+

Chapter XII, The Wys by which satan Enters

the Heart. 2 6. ee ee ee 12he

Chaptor XIII. That for which lan is Held

Aecountable, and that for vhich He is

Forgiven. 2 se ee ee e+ 1600

Chapter XIV. Are Evil Promptings Entirely Cut

Off by Devotional Exercises? . . . 170.

Chapter XY, The Rapidity of the Heart's changes 178.

oC

BERRA Ore DE Piet ore tole or) ee eee eat 2295

adi,

INTRODUCTION,

A, A Blographical Sketch of Al-chazréli.

AbG Faimid Wubammd bin uubammd ‘bin Mukasmed bin

Apmnd al-Ghassili el-Jist was born in fis, Persia in the year

450 A.H. (1058-9 A,D,) and died in SOS/1111. Bis biography has

‘been thoroughly studied and sympathetically written by competent

fy)

and an understanding of his life is indispensible

a) These biographical sources are: D, B, lacdonald, The Life of

AlcGhazzG1i, Journal of the American Oriental society, xx, 1899,

PP. 71-132, and his article in the Encyclopaedia of Islam, 41,

Pp. 146 ff; S. M, Zwomer, A Moslk

Seeker after God, Revell,

New York, 1920; W. R. W. Gardner, Al-chazdlf, in The Islam Series,

of the Christian Literature Society for India, Uadras, 1919. To

‘these should be added two articles by Macdonald in Ieis, May 1926,

PD. 9-15, and Way 1937, pp. 9-10, which mke another needed clari-

fication of the misapprehension of some Western medieval scholars

regarding al-Gharzéli's purpose in his mgapid al-falasifah; also

@ modern Muslim appreciation by S. U. Rahman, Al-Ghaszalf, in

Islamic Culture, July 1927, pp, 406 ff, For readers of Arabic

mention should be mde of the following recent works: gbd pamid

al-Ghazeadli by wubamad Rigs, Cairo 1343/1924; al-akhlag (ind 7

ive

for eny adequate understanding of his principles of religious

psyrhology as found in this book from his great work, ibys

‘alin

fin, Only e brief summery of the principal

his life can be given here,

Al-Gharzili's father died when his: son-who wis. to

achieve such fame was tut a smll boy. Before his death the

father gave his two sons into the charge of a sift friend who

faithfully cared for them and began their training, Al-Ghazza12

studied in a madraseh in fis, and later in Jurjén and Nishapor,

In this last place his teacher was a famous and devout part, abé:

L-tatG1f ‘abd al-imlik al-Juwaini, better known as Indu: al-faremin,

Al-Ghas:

remained: with him as his pupil and probably also hin

acaistant until the death of the Imim, He was a faithful student

and acquired a broad knowledge of many branches of learning, By

Qlcchagsilt, by Zaki Mubsrek, Cairo 1343/1924; pafwat ihya? al-

Ghazr@l%, by Mabmid ‘Alt qirifah, Cairo 1353/1935. For a list of

the writings of al-Ghazs@li see Ency. of Islam, op.cit.; Brockle-

mann, i, pp. 421 ff. & euppe/abe 144 ff.5 also the books mentioned

above by Zvener and Muhammed Rida, A List of thirty-eight of his

best known and most easily obtaimble writingsis given in the

appendix of Gardner's Al-Ghazali, pp. 105 ff.

ve

his diligent application and constant stady he probably did a

lasting injury to his health at this period of his life.

after the death of the Inim al-faremin, al-Ghezziif

vont to the court of the great visier, Nigam al-wulk, where he

von fame and praise for his learning. fe was later appointed to

teach in the great school at Baghdad, and there he lectured to

some three hundred students, and gave legal opinions of great

importance. He preached to large and appreciative crowds in the

Bosque, and he prospered in material things.

Brt although he was outwardly succossful, bo had pe

Peace of heart. He was experiencing a deep and lasting change in

his life, In all his study and learning he had not found reality,

and he was now plunged into the depths of skepticiem, He sought

the answer to the doubts of his soul in scholastic theology, in

the teaching of the Ta‘ limites who said that one must follow an

infallible living teacher, and in the study of philosophy, but

the result was not satisfying. He turned to the study of sifien,

and then realized that whet he needed was not so much religious

instruction as religious experience. He saw that his own life

was so full of sham and covetousness that if he continued thus

he could not possibly find rest or reality, His mutel stato so

affected his physical condition that it was impossible for him to

continue teaching.

So in the year 488 he suddenly forsook position, wealth,

and fame and withdrew from the world. ‘The brilliant teacher who

had gloried in worldly success and royel favor now turned his back

upon 4t all and became & wandering dervish ascetic. He had been

given divine grace te renounce a21 for an experiential knowledge of

Allah, He lived in retirement in Damacus, visited Jerusalem and

Hebron, mide the pilgrimge to Mecca and Wedina. Finally, drawn

by the ties of family affection and recognising the propriety of

such relationships, he returned to Baghdid. ‘This period of re-

‘tirement and wandering wis filled with ths preetice of devotiom)

exercises, and the study and writing of tooks. karly in this

period he wrote bis mei

piece, ihyé? ‘uldn al-din, and he taught

it in Damascus and Baghdad. It is quite peesible that he revised

this work at a later period in his life.

Al-GhaseGli‘'s return to pablic life cam in 499 when he

wes appointed to teach in the school at Rishapur; but only for a

short time did he remain there. He desired the life of retirement

and meditation on spiritual things, end so removed to his native

city of Jas where he established « gfiff school and khangéh. There

ho spent hie time in study and meditation until his end came

quietly in the year 505/111.

From his own day up to the present time al-Gharsali has

held a secure position of leadership in Islam. with him the

religious philosophy and experience of Islan reached its senith,

vil.

and the syst

of ethics which he produced has become the final

authority for orthodox Islam, His was

warming and revitalizing

influence upon Islam in his own day, and it bas contimed to be

such ina potent wy for eight and a quarter centuries, ‘The

vitality of bis experience, the breadth of his leerning, the high

Plane on which he lived his own transformed life, and the depth of

hie desire to serve Ailah and his fellowmen in complete and self-

denying devotion mde him the mn whose influence is considered

by many to have been second to none among the leaders of Islam,

save thet of Muhamed himself, a

Al-Sayyid al-wurtada al-zabidi, in his commentary on the

Thyis called ith@f el-sfideh al-wuttagtn, bas a lengthy treatise on

the life end influence of al-GhassGlt. In it he shows how mny

Muslim writers have used al-Gharsa]i's books and ideas as a basis

for their own thinking and writing, ‘The fact that new books on

al-Chazsalf are still being written by modern Wuslim writers and

by Western orientalis

4s conclusive evidence of his high place

in the world of welim thought. Jabran rhalfl Jabrin, well-known

29 a writer both in English and arabic, wrote of al-Gharsalf in

bis book al-badé?if wal taravif, Cairo 1923, pp. 116-118, as

follows:

"Al-Gharsélf holds « very high place in the minds of

Western orfentalis

and scholars. They place him along with

wiht,

Ton Sima and Ibn Rushd in the first rank of oriental philo-

sophers. The spiritually minded among them consider him te

represent the noblest and highest thought which has appeared

in Islam. Strange to say, I saw on the walls of a church in

Florence, Italy, built in the fifteenth century, a picture

of al-Gharzili among the pictures of other philosophers,

eseints, and theologians whom the leaders of the Church i>

the middle ages considered as the pillcrs end columns in

‘the temple of Absolute spirit.

"But stranger than this ie the fact that the people of

‘the West know more about al-Ghazzali than do the people of

the East. ‘They translate his works and investigate his

teachings and search out carefully bis philosophic contentions

and aystic aims, But we, who still speak and write Arabic,

seldom mention al-Ghareli or discuss biz, Ye ere still

wasied with the shells, as though shells were all thet come

out from the sen of life to the shores of days and nights."

Another quotation will be given frou a book used in

Egyptian secondary and teacher training schools in the study of

the history of Arabic literature. It is al-wastt fi 1 *édab el-

farabi wa tértkhibi , by Shaikh Abmsd el-Zekandari and Sheikh

Mugfafa ‘aAnnant, Cairo 1925, as follows:

"There ic a real soul bond between al-Ghazzalf and St.

ixe

Augustine, They are two similar appearances of one principle,

in spite of the sectarian and social differenc

existing

between their times and exviroments, this principle is an

instinctive inclination within the soul which leeds its

Poasessor on step by step from things seen soi their exterml

appearances to the things of reason, philosophy, and divinity,

“Al-Ghazsé1% seperated himself from thyworld and from

the luzury and high position which he had in it, and Lived

the lonely solitary life of a mystic, penetrating deeply into

‘the search for those fine threads which join the utmost limits

of acience to the beginnings of religion; and searching dili-

gently for that hidden vessel in which men's perceptions and

‘experiences are mingled with their feelings and dreams,

“Augustine had done this five centuries before him. Who~

ever reads bis book ‘Confessions’ will find that he took the

earth and everything derived therefrom as e ledder on which

to mount up to the secret thought of the Supreme Being.

“However I have found al-Ghazs&if to be nearer to the

real

ence of things and their secrete than St. Augustine

was, Perhaps the reason for thie lies in the difference be~

‘tween the Arab and Greek sciontific theories which preceded

his time to which the former fell heir, and the theology

“< which occupied the fsthers of the Church in the second and

x

‘third comturisa A.D,, which the latter inherited. By in-

herdtance I mean the thing which is passed on with the age

from one mind to another, just as certain physical attain-

ments are cénetaxt in the exteronl appearance of peoples

from age to age.

“I found in el-Ghaszilf that which makes him a golden

Link joining the mystics of India who had preceded him with

the eeekers for the divine who followed him, For in the

attaiments of Buddhist thought there 4s something akin to

al-Gharséli; and likewise in what Spinoza and William Blake

have written

modern tines there is sonething of his feelings.

"Al-Gharzali is considered as a supporter of the Ash‘ard

sect enlled the people of the Sunnah, and as one of the great~

est of shaft‘fimems, He is reckoned as the best of those who

spoke on asceticiom, being unlike to the sift sects which

went beyond the ordinary experience of the human reason. His

‘book, ihya’ ‘ulfin al-din, is one of the finest books on ac-

coticiom, ethics, -. and exposition of the wisdom of the

quran and the shart‘ah. Bis writings on these subjects are

most eloquent, and his etyle of writing is aimed at ty

scholars in this field and by other reformers evén up to the

present tine,*

As a writer al-Ghazralf was not original in the use of

‘the mterial which he incorporated in his many books. ‘This was

only natural in the light of his experience of study and search

for truth from so many different sourc

Ho was influenced by

all the systems which be studied,and appropriated for his own

teaching what he deemed to be the truth wherever he found it.

He followed the teaching of the proverb he quoted, (p. 151),

“Bat the vegetable wherever it comes from, and do not ask vhere

the garden is.* He took such from his

dy of the philosophy of

al-Férabi and Ibn Sina, especially the latter. He constantly

quotes from the git eal-quitib of Abd JElib al-Makkt and alerisalah

gicgushsiriyyehs and he shows the influence of al-parith al-mubasitt,

AG Msfd al-pisfind, al-shinit, and others whose works he studied.

Tn summing up an article on al-Ghazsilf's debvt to al-

»)

ibi, Dr. Wnrgaret smith writes, “These emmples ... . show

clearly al-Ghazzali's indebtedness to his great predecessor,

vot for the min trend of his ascetical, devotional, and

mysties! teaching and for mny of the ideus and 11lustrations

of which he mkes use in his rule for the religious life." . .

“The foundations of that great system of orthodox Islamic

mysticism which el-Gharsilf mde it his tusiness to bring to

completion, had already been well and truly leid,*

xGlf, Field, London 1909, p. 41.

a)

b) The Forerunner of sl-Ghasil, JRAS, 1936, pp. 65-78.

But al-GhassGli did more than merely cite quotations

from these sources; he wove thom into a harmonious system based

upon his own experience of gaining and realizing reality. His

hole morel philosophy wes a synthesis, and a practics] expression

of the golden mean, He took the rigid framework of the scholastic

theologian and clothed it with the warm personal foith of the

mystics To the knowledge of the philosopher which is gained

through the processes of study, reasoning, and deduction he added.

the inner knowledge of the sift vho

with the light of cor

tainty, and experiences dirdct revelations and unveilings of the

Divine Reality, He was careful, however, to avoid the extreme

Yagaries of pGfiem and especially its tendencies to antinomianien

and pantheism, fe united the best results of philosophic specu-

lation with orthodox Islam, and, while denying the usterialiam of

the philosophers, he nevertheless used their mothods to develop

bie own thought, end to refute them where they differed with the

teachings of orthodox Islam

Al-GhaszG1i was well acquainted with the technical

language of all of these different groups and used it to express

his own idoas, but he often quoted it quite loosely, Similar to

this was his imcourate use of tradition for which he bas been

eriticized ty both his friends and his foes. He quoted traditions

carelessly and often inezactly, But even more serious was his

xiii.

uncritical selection of traditions, muy of wich were very

poorly attested or even quite unfounded, according to the best

authorities, Perhaps the explanation of this strange inezct-

peas in such e learved mn lies in the fact that al-chazzalf,

with all his learning, was less = theologian, a philosophor, a

traditionist, or even a sift mystic, then he was a preacher and

teacher whose great end and aim was to move men's lives and to

tarn their hearts to seck allah. Im his spiritual enthusiasm to

gain this end he was often careless in the formlation of the

statements and quotations which he used es « means of attaining it,

Al-Ghas2G1% pot great emphasis upon man's need for

spiritual leaders, and his Thy’ gives the ethical teachings of a

Kindly pastor who cares for his flock. He was considerate and

humane in his dealings with men in general, and, although reviled

by others, he was slow to condemn those who disagreed with hia.

Even when he did condemn the philocophers his chief concern wee to

point out the errors of their system of thought and teaching,

rather than to denounce them persomlly.

xive

B. A Sketch of Al-Ghazzali's Psychology.

Introduction.

Ts taking up a somewhat systemtic study of the pey-

chology of al-Ghaszili it will be observed that many of his ideas

follow closely those of the philosophers whose heretical doctrines

he opposed so strongly. But, no mtter how much my be said about

his borrewings from the Greeks and their successors, we must take

care not to consider him as a mere eclectic philosopher who took

what he chose from hie predecessors, for he was first of all a

Muslim teacher and preacher. He weighed all of the teachings of

‘the philosophers in the balance of the Islamic faith, and incor-

porated into his system only those principles which measured up

to that standard. In so far as he did follow the philosophers

he adapted and modified their teachings so ae to make them conform

to the orthodox Wuslim religion,

‘The psychology cf al-Ghareai was Platonic in many of

Lie ideas, but it included much of the Aristotelian development in

ite analysis, Neoplatonic thought which had so strongly influenced

al-Firabi and Ibn sina was inevitably present in the thinking of

al-Gharralf also, and it colored many of his philosophical and

psychological concepts.

The fact that al-hazzéli uses the term ‘heart’ -

xv.

instead of soul in the title of this book is an indication of the

primal position this word had in the vocabulary of iuslim religious

teachers, end also in that of the philosophers, ‘The term was used

in Islam for the seat of intellectual and emotioml life even as

it had already been used by Judaism and Christianity. Among the

Greeke and Romans the heart took the place ir the liver as the

a

soul, intellect, and emotion, 4ristotle gave the

>)

heart the place of honor as the seat of the noblest emotions.

seat of 1if

Although al-Gharzili uses the term ‘secrets’ of the

heart as a synonym for its ‘wonders’, it apparently does not con-

note any special mystical signification, elthough it has such a

e)

meaning in $Gfi usage. ‘The heart is the seat of secrets.

Al-GhazzGli limits the discussion of the subject largely

to the field of practical religious philosophy (¢ilm el-m¢dmlah),

His eim is ethical, and, although he does at times inevitably deal

with questions of metaphysics, it is nevertheless with ethics thet

he is primnrily concerned. He would not go as far as zeno and

4)

/

reduce all virtues to practical wisdom (Ppo ¥7d1S), yet thet was

a) Hastings, Ency. of Religion and ethics, vi. p. 557.

b) Brett, A History of Psychology, i. p. 106; Ross, Aristotle,

pe 143, m1.

¢) Dict. of Tech, Terms, p.. 653.

4) Usverweg, A History of Philosophy, i. p. 200.

for him the important way of achieving his desired end, - the good

a)

life

He agreed with Aristotle that understanding included both

wisdom (sopra) and practical sense (ppovqers 8) but what he

stressed was thqlatter, which they both held to be "practical

ability, under rational direction, in the choice of things good

tnd avoidance of things whieh are evil for ann.” This practical end

was kept ever in view by al-Ghaszalf as the logical outcome of

man's tmowledge and experience.

1, ‘The Nature of the soul,

In order to understand clearly al-Gharzali's concept of

the nature of the heart, or soul, it is necessary to discuss féur

terms which are applied to it. They are: ‘heart’ (galb)y ‘spirit’

(rh); ‘woul’ (nafi

j end ‘4ntelligence’ (¢ngl). Zach of tl

terms bas two meanings, but the second meaning of each term is

the same as the second meaning of each of the other three terms.

‘The term ‘heart' means the heert of flesh in the body of

2 man or animal, whether living or dead; but it also means that

subtile tenuous substance, spiritual in nature, which is the knowing

a) wure, Aristotle, p. 129.

b) Brett, op. cit. 4. pe 144,

c) Ueberweg, op. cit. i. pe 176.

xvii,

and perceiving

nce of man. There is sone connection between

the physical heart and this spiritual theart', but practical

wisdom and prophetic precedent do not demand nor warrant the ex:

plamation of this relationship,

‘Spirit’ means that refined mterial substance which 1s

Produced by the blood in the left cavity of the heart and which

rises up to the brain and pe:

8 to all parts of the body through

Perception, This resembles Aristotle's theory of the TreSpe

ae a “sentient organism of a subtle nature spread through the

vody and acting as the universal medium of sensation, 2 ‘Spirit’

also mens the above mentioned subtile spiritual substance which

is the second meaning of ‘heart’.

The third term is ‘soul’ (nafs), This my mean the

*)

life-giving soul whose sent is in the heart. surjént defines

mife ae “that refined muporous substance (jawhar) which bears the

Powers of life, sense perception, and voluntary motion", and says

that al-fekim (Ibn Sina) called it the anim spirit «

elzhayewéniyyeh), Al-Ghazsi1i and othe> sift writers commonly

8) Ithdf, vid. p. 203; note 20, p. 192,

d) Brett, i. p. 119.

¢) Ency. of Religion and Ethics, 1. p. 679 b.

xviii,

bring the word nafs, which is the ordinary Arabic equivelent for

the ypuyny of Greek philosophy, down to the appetitive soul

(€cOuple ) 45 which are united man's blanovorthy qualities,

‘This is the pura of Pauline theology and the nephesh of

Hebrew. It is not clear fron this book of the Thy’, nor from

his méGrij al-quds ft mdarij m‘rifat el-nafs, or el-risflah

alcladunniyyah, or kimiya? al-setédah, whether or not al-chazzal?

held that the ‘soul' in this sense was mterial or imeterial in

ite nature. Some hints of a mterial soul are found, for exemple

in kimiya’ al- satan” vere he speaks of the nafs as the vehicle

(marked) of the heart, a term usually applied to the bodys and

again in el-risflah al-tadunntyyan ere he says that gifts call

‘the anim] spirit (gl-rih el-heyawini) e nafs. the clearest hint

is perhaps that in ofsin e-em vnere he speaks of the two

Meaningsbf the soul as the animil soul (el-nafe el-bayawaniyyeh)

and the human soul (al-nefs al-ineniyyeh). It is clear that there

wes in Islam the concept of a mterial a) But al-cherzili does

not stress the nature of this appetitive soul as regerde its

a) Gairo 1343, pp. 8) 10,

b) Cairo 1343, p. 27.

¢) Cairo 1342, pp. 18, 20.

4) Vacdomald, The Development of the of spirit in

Jurjant; Dict. of Tech. Terms, pp. 1390 ff.

ix.

materiality or immateriality, but rather es regards its charset:

istic of uniting the blemeworthy qualities of mn, These blame-

worthy qualities are the animal powers in mn which are opposed

to his rational preety Tt is thus, like Plato's irrational

soul, made up of anger (ghadab, Quuss) and appetence (shahweh,

em Bun fay,

‘The second meaning of mafs is that subtile spiritual

substance which is the real essence of mn.

‘The fourth term is ‘intelligence’ or ‘r

jon" (fagh).

Tais rord is commonly used to translate the Greek VOUS . ‘Aah

is applied to man's knowledge of the true mture of things, and

also to hie pover to perceive and know, This letter meaning is

that same subtile spiritual substance of which Aristotle said,

"Reason, nore than anything else, is ers

It 4s this second meaning, common to all four terms, of

which al-chazrélf writes in the volume before us. Thus his con-

sept of ‘heart', or ‘soul’, may be defined as that subtile tenuous

substance, spiritual in nature, which is the perceiving and knowing

essence of mn, and in reality is mn, Its seat is the physical

heart. It is immterial end immortal. It is created directly by

a) mGrij al quds, Cairo 1346/1927, p. 11.

>) Micomachean Ethice, 1177 b 26-78 a 7, in Mure, Aristotle, pel65.

Allah, capable of knowing Him, and is morally responsible to Him.

Al-GhazzG1f, following Ibn Sima and other Areb philo-

sopkers, conceived of the human soul as being between the lower

realm of the animal and the higher realm of the divine, end es

partaking of the characteristics of each of these ea the

elaboration of their doctrine of the soul they combined the id

of Plato and Aristotle, and joined to them additional ideas from

Neoplatonic sources. Perhaps the most systemtic statement of

the resulting doctrine of the soul is that given by Ibn sim

which my be summarized in the following scheme which is adapted

>)

from Rastings, Zncyclopeedia of Religion and Ethics, ii. pp.274 f,

(Vegetative soul

(

Soul

= tea Soul

(Ruman (Rational) Sou)

Bach one of these divisions is furth:r subdivided as follows:

(Powers of nutrition

¢

Vegetative Soul ---- ( " "growth

¢

¢

" "reproduction

a) Brett, ii. p. 48g Plotimus, Enneads, IIT, ii, 8.

b) Cf. Brett, ii. pp. 54 ff.; Islamic Culture, April 1935, pp. 341 ff,

(attractive powor

( (concupiscence)

(Appetitive _.

(power

( (repulsivs power

Motive (| Graseipility

faculties ( (and passion)

( (Bfficient

( { power in motor nerves

( and muscles

Animel soul-(

(

( (sight

{ (hearing

(

(

(Perceptive.___(

(aculties —(

{ ‘common sense

[formative faculty

(internal (cogitative *

(estinative *

(memory

{active Intelligence

(practical reason)

Human or ¢

Rational --- ( (material intellect or

Soul f {potentiality of knowledge

(Speculative Intelligence (intellect of possession

(| (theoretical reason) (| recognizes axiomtic

perceives __( —_ knowledge

Ade uy "77" (perfected intellect

("lays hold on

(| Antelligibles

‘This system was adopted in large part by al-chaszilf, and it formed

the framework of his intellectual philosophy.

In analyzing the above scheme as developed by al-Ghassalt

xxii,

in this book we find ideas corresponding closely to the Platonic

thought of the rational and irrational eer p rational soul,

according to Plato was created by God and placed in the heed, bat

the irrational part was the creation of the demiourgoi. Ite

nobler part is anger, or the spirited, irascible nature ( Bupes),

and has its seat in the heart or thorax; while the base part which

is appetence, cr the concupiscible nature (emiBupia), hes its

seat in the abdominal cavity,

For al-Ghazz@lf, of cours

Allah is the Creator of-all

that man is and does, and he follows Aristotle in holding thet the

heart is the seat of the rational soul. fut, in spite of th

differences, the Platonic division is an importent zart of the

thinking of et-otmasitt. patore ‘rational soul' is el-Ghazzali's

‘soul or theart' or ‘intellect’, depending on the illustrations

he uses, ‘The irrational soul of Plato includes the powers of

appetence and anger which, for him and for el-ChazzGli too, must

be held in check by the rational soul or intellect. when the in-

tellect dominates these lower powers justice is established for

‘both soul and body, but when the lower powers dominate the intellect

it becomes their slave, ‘The excellence or virtue of the rational

a) Brett, i. p, 68; Timous 448, 692,70 B DE. Cf. Aristotle,

De Anima, yi; III,ixg Plotinus, Enneads, IV, viii, S-8

b) Cf, note 23, p.193.

xxiii,

soul is wisdom, thet of anger is courage, and that of appetence

a)

is temperance.

Even more clearly do we see the Aristotelian analysis

in al-Gharzili‘s psychology with its vegetative, animal, and humo

b)

Aristotle tried to explain accurately the phenomem of

e)

peychic life, approaching it from the side of metaphysics. All

‘souls

known things are included in an ascending scale from pure matter

to pure form, The body alone is mtter, end the soul alone is

form. The sphere of psychology is the relationship of the two

(To & Yelov ), soul and body must be defined in relation to

each other, the soul is the true essence of that which we call

body, and is man in reality, It is the first actualizetion

(entelechy) of the tody, and represents a possibility of psychic

activity. ‘The second entelechy is the actual realization of this

possibility. ‘This is illustrated in the eye which has the power

to

even when that power ie inactive, as in sleep; and the eye

which is actually s

ing. Al-Ghazzdli holds quite a similer

position, and gives the same illustration of powers potential and

a) Brett, 4. pe 97.

b) De Anim, II, is III, ix; wre, Aristotle, pp. 95 ff.

Sf. Plotinus, Saonsads, III, iv, 2, Note 56, p. 197-

¢) Brett, 4. pp. 100 ff.

xxiv.

actual,

Man's power of reaction is three-fold: He absorbs

nourisbuent and reproducs

8 does the plant. He has

nse pore

ceptions, powers of discrimimtion, and voluntary movement like

the animal. He differs from them both in possessing rational

Power, and is capable of that higher knowledge which includes

the knowledge of Allah. By virtue of this quality of experiential

knowledge min occupies @ place between the animls and the angels.

“There ere in him the desires of the beast united with a reason

that’ ie goattie. «py neglecting the retiom soul he can sink

toward the level of the animl,and by cultivating it he can strive

toward the level of the angels.

2. The Soul's Knowledge and the Means by which it is acquired,

According to the Neoplatonic idea of mn, "Krowledge is

>)

always an activity of the soul." ‘through this activity man gain

a firm and lasting grasp of reality. Al-Ghazza1% held that man's

peculiar glory is the aptitude which he has for that highest of

all kinds of knowledge, the kuowledge of Allah, In this knowledge

is man's joy and happiness. The seat of this knowledge is the

a) Brett, 4. p. 137.

‘b) Brett, 4. p. 305.

heart, which: was created to know Him just as the eye was created

to see objective forms. The physical members are used by the

heart to attain the end of knowledge even as the craftsman uses

his tool to accomplish his purposes. wan's potential capacity

for knowledge is practically unlimited, that is,

ve by infinity

itself.

Although kmowledge my to a cortein degree be the result

of man's activity, yet it requires « cause outside of man himself

to bestow true wisdom. Plato found this outside cause in the world

of Ideas. Aristotle

id that intelligence ( VoUS) comes into

a)

man “from without es something divine and immortal". Intelligence

is not a mere function of the matural body. ‘Knowledge

med to

the Arab to be an eternal and abiding reality, . . . which fora

»)

time reproduced itself in the individuel,”

Man is potentially capable of knowledge because of the

°)

principle that like can know like. The old Greek idea of mn as

a)

4s accepted ty al-chazzili, vho

@ aicroco: id, (pe 81), "sees

were it not that He has placod an image of the whole world within

a) Usberweg, i. p. 168, Cf. Brett, i. pp. 153 f,

b) Brett, 44. p. Sl.

c) Plato, Time:

37 B Gg Introd. p. 10 (Loeb Classical Library).

4) Soe note 127, p. 207.

xxvi.

your very being you rould heve no knowledge of that which is

apart from yourself." He further develops this idea in ktmiya?

a)

"Know that mn is an epitomy (mukhtasarah) of the

vorld in which there is a trace of every form in the world, For

the

bones are like the mountains, his fleeh as the dust, his

hair es the plants, his her

as heaven, his senses as the planets,

seserseThe power in the stomich is like the cook, that in the liver

like the taker, that in the intestines like the fuller, and that

which makes milk white end blood red ie like the dyer," In man

there are many worlds represented, all of which serve him tire-

lessly although he does not know of then nor give thanks to Him

who bestowed them upon him.

Al-Gharzili also uses the Pletonic idea of man being

»)

the copy of the archetype, He connects this with the yuelim

¢)

doctrine of the Preserved Tablet (al-lewh al-mhfas), the

Archetype of the world was written on the Tablet. ‘The real nature

of things is mde known to man by disclosure to him of what is

there: written through the reflection of the:

truths in the mirror

of the heart.

a) Gairo 1343, p. 19,

b) Timeus, 37 0 8; translation, p. 79. Cf. Plotinus, eds,

TIT, viii, 10; vy 4, 45 VI» vid, 15.

©) See note 111, p. 205.

xxvii.

a)

‘This introduces us to the example of the mirror which

is a favorite of al-chazzéli's, ian‘s heart, es e mirror, is

potentially capable of having reflected in it the real a:

nce of

all things, end thus of coming to know them, In this knowledge

there are three factors: (1) The intellect, or heart, in which

exists the image of the specific matures of things, is like the

mirror. (2) The intelligible, cr specific nature of the known

thing, is like the object reflected in the mirror. (3) The in-

telligence, or the representation of the known thing in the heart,

is like the representation of the image in the mirror,

‘The reflection of knowledge in the heart my be prevented

‘vy one or more of five causes: (1) The heart of a youth is ina

crude unformed condition and is incapable of knowledge, just as a

crude unpolished piece of metal is incapable of reflecting objects.

(2) Disobedient acts tarnish and corrode the mirror of the heart

so that the reflection of reality therein is dimmed 2r destroyed.

(3) van my not know Allah because his heart is not turned towards

fim, even as the mirror doss not reflect the desired object unless

it is turned towards: it. (4) The heart my be veiled to true know-

ledge ty blindly accepting dogmtic teaching without understanding

or thought. (5) The heart my not even know in which direction to

a) Cf, Plotimus, Znne

weviit.

turn in order to have reality reflected in it.

Wan can polish end turnish the mirror of his heart by

means of acts of obedience so that it vill reflect the image of

true reality. He thue gains knowledge by mking it possitle for

the image of the archetype to be reflected in his heart.

‘The sum-total of mn‘s knowledge is thus rooted in his

knowledge of himself, He knows only himself in the proper sense,

and knows other things only through hirself. This is true also

of man's highest attainment of knowledge, the knowledge of Allah;

for the quality of the Divine peing is reflected in the humn soul.

"He who knows himself knows his Lord" is the true statement of

tradition. Every heart is thus a microcosm and a mirror, and

being thus constituted is capable of knowing self and the divine

‘The heart of min bas two kinds of knowledge: intellectual

and religious?” utellectual knowledge my be the intuitive know

ledge of axioms, or acquired knowledge which is the result of study.

Acquired knowledge my deal with the things of this vorld, such ss

medicins, geometry, astronomy, and the various professions and

trades; or it may be concerned with the things of the world to come,

such as the doctrines of religion, Speculative theologians stress

a) Gf. development of microcosm and mcrocosm in Windelband,

A History of Philosophy, trans. by Tufts, New York, 1907, pp. 366 ff.

b) cf, tabl

on pe Ist.

xxix.

this sort of acquired knowledge ae being most important.

Religious knowledge is the knovledge of Allah, His

attributes, and His acts. It is accepted on authority by the

common people as dogue ina blind and unreasoning fashion which

has in it nothing of direct inspiration, To people of deep re-

ligious experience, horever, this knowledge is given directly.

Saints and mystics receive it through general inspiration (i1him),

while it is received by prophets directly from the angel through

prophetic inspiration (wahy).

Both intellectual and religious txowiedge are needed

and neither one is sufficient without the other. ‘his is true in

spite of the fact that each tends to exclude the other except in

the case of unusual men who are both learned and saintly. Intel-

lectual knowledge may be compared to food, and religious know-

ledge to medicine. Both are needed for the preservation of health.

Even as there are two kinds of knowledge which enter the

aeart, so also the heart has two doors by which this knowledge

pemeetctat nen eee to the knowledge of material

things which is sense perception, The inner door is thet of divine

ingpiration and ayetical revelation. i again the principle

obtains that like knows like, for the senses belong to this present

4) Dict. of Tech. Terms, p. 371; asin, Algezel, pp. 79 f.

b) Gf. Plotinus, Enneads, V, i, 125 ITI, vidi, 9

world for which they were created, while the heart belongs also

to the invisible world of the spirit (el-mlakit).

The external senses of sight, hearing, smell, teste,

and touch act through the bodily members: the eye, ear, no

tongue, and fingers, Sense perceptions reach the individual by

means of these external senses, but they are perceived and under-

stood only by means of the five inner sens

which ere (1) common

sense or sensus comm

(hiss mushtarak), (2) retemtive imgination,

(khayal, takhayyul), (3) reflection (tafakkur), (4) recollection

(tadhakkur), and ($) memory (pif), ‘These ere internal powers end

their seats are internal,

Fore al-Ghazzé2i follows loosely Ibn Sima's developnent

of Aristotle's views on these inner oe ‘The common sense is

thet power which receiv

the impressions which come through the

different external senses and unites them into a harmonious and

unified whole, Retentive imegination is thet power which takes

from the common sense the physical tion and transforms it into

a psychic pes

sion, This power is located in the front part of

the brain. Reflection is the pondering, cogitative faculty of the

heart. Recollection is the power to recall the mental ‘mges of

a) Cf. Aviconma's offering to the Prince, Yan Dyck, Verona 1906,

pp. 65 ff, and other references in notes 37 & 38, pe 195.

past sensations which have been forgotten for a tine.

mory is

‘the storehouse for the meanings of sensible objects formerly per-

ceived. Its seat is in the tack pert of the brain.

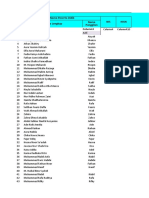

‘This list of the internal senses differs from some other

classifications of them by al-chazzali, Five other lists will be

Presented in tabular form, In this book el-chazzéli deals vith

practical and ethical ends, and perhaps did not feel thet it was

necessary to be scientifically accurate in his statement. xt will

be noted that the classifications given in the first four of the

books as tabulated below are definite ettenpts to present the sub-

Ject systemetically. It would be of added interest if we could

know for certain the chronological order of the:

ooks. It ape

Pears to be quite safe to put the moisid and tahafut first.

uizGn el-‘amil is pleced third because it seens logically nearer

to the firet two than does mé¢arij al-quds ff mdi [m‘rifet

alcoafs,(aiso known es méérij ea-sinsin)) The analyses given

in the pizén and ma‘Grij are particularly worthy of note

s being

systemetic and deteiled in forn, end as coming from the later

period of al-GhazzGli's life, ‘he list from kimiy? el-se‘&deh

is given as an interesting parallel to that in this book of the

8) Brockelmnn, supplement, i, p. 751.

he

2.

3.

5.

magisid

Common sense

hiss mshtarek

Retentive

imagination;

Conservetion

sutagewrirah;

Ghnk

anterior ventricle

Istimetion

webmiyye’

posterior

ventricle

Compositive animl

& human imegination

mutakhsyyilah

mufakkireh

middle ventricle

Memory

chékirah

posterior ventricle

tabafut

common sense;

imegination

piss mushterek;

Khayeliyveh

retentive

imagination

pefizeh

‘Estimation

wehmtyyeh

posterior

ventricle

compositive enimal

2 human imagination

mutathayyilah

mufakkireh

middle ventricle

memory

dhdikireh

posterior ventricle

xxii.

mizén

conmon sense;

imeginetion

hiss _mushterek;

Khayaliyyeh

enterior ventricle

of brein

retentive

imegination

néfizen

anterior ventricle

Estimation

wahmiyyeh

end of middle

ventricle

compositive animal

& huran imeginetion

mutakhayyilah

mufekkirah

aiddle ventricle

memory

ahékireh

posterior ventricle

Le

2

3.

4

5.

me Kiniyd?

Common sense; imagination

phantesia; tablet

hiss mushtarek; khayél

Hess muphtare®: shaved,

bintisya; lawh

front of anterior

ventricle

tentive imginetion estimation

am

teck of anterior

ventricle

Estimation reflection

wahni yyeh tefekkur

whole of brein, but

especially teck of

middle ventricle

Compositive imagina- recollection

tion, anim ¢ humn

tal mutakhay- tadhakkur

mufekkirah

front of middle

ventricle

Yenory zemory

Rifizeh; dhékireh ify

posterior ventricle

xxii,

ihy?, iii. 1.

cormon sense

pis:

nushterak

retentive imeginetion

kheyél; tekheyyul

anterior ventricle

reflection

tefekkur

recollection

tedhakkur

> memory

hifz

posterior ventricle

You might also like

- Qira'at Hamza AzzayatDocument68 pagesQira'at Hamza AzzayatQuraan Sheikhah100% (2)

- Ghazali on the Principles of Islamic Sprituality: Selections from The Forty Foundations of Religion—Annotated & ExplainedFrom EverandGhazali on the Principles of Islamic Sprituality: Selections from The Forty Foundations of Religion—Annotated & ExplainedRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (6)

- William Chittick - Ibn Arabi's Own Summary of The FususDocument44 pagesWilliam Chittick - Ibn Arabi's Own Summary of The FususQazim Ali SumarNo ratings yet

- Roberts Avens - The Subtle Realm - Corbin, Sufism, SwedenborgDocument10 pagesRoberts Avens - The Subtle Realm - Corbin, Sufism, SwedenborgQazim Ali Sumar100% (2)

- Pablo Beneito (Ibn Arabi) - The Servant of The Loving OneDocument14 pagesPablo Beneito (Ibn Arabi) - The Servant of The Loving OneQazim Ali SumarNo ratings yet

- Divine Timeless Secrets In the Amazing Story of Musa and KhidrFrom EverandDivine Timeless Secrets In the Amazing Story of Musa and KhidrRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Illuminating Lantern: Commentary of the 30th Part of the Qur'anFrom EverandThe Illuminating Lantern: Commentary of the 30th Part of the Qur'anNo ratings yet

- The Call of Modernity and Islam: A Muslim's Journey Into the 21st CenturyFrom EverandThe Call of Modernity and Islam: A Muslim's Journey Into the 21st CenturyNo ratings yet

- Islamic and Modern Scientists' Viewpoints on the Future of the WorldFrom EverandIslamic and Modern Scientists' Viewpoints on the Future of the WorldNo ratings yet

- The Hidden Treasure: Lady Umm Kulthum, daughter of Imam Ali and Lady FatimaFrom EverandThe Hidden Treasure: Lady Umm Kulthum, daughter of Imam Ali and Lady FatimaNo ratings yet

- Quest for Islam: A Philosopher's Approach To Religion In The Age Of Science And Cultural PluralismFrom EverandQuest for Islam: A Philosopher's Approach To Religion In The Age Of Science And Cultural PluralismNo ratings yet

- Seâdet-i Ebediyye Endless Bliss Fourth FascicleFrom EverandSeâdet-i Ebediyye Endless Bliss Fourth FascicleRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Ibn-Daqiq's Commentary on the Nawawi Forty HadithsFrom EverandIbn-Daqiq's Commentary on the Nawawi Forty HadithsNo ratings yet

- Irfan: A Seeker’s Guide to Science of ObservationFrom EverandIrfan: A Seeker’s Guide to Science of ObservationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Knowledge before Action: Islamic Learning and Sufi Practice in the Life of Sayyid Jalal al-din Bukhari Makhdum-i JahaniyanFrom EverandKnowledge before Action: Islamic Learning and Sufi Practice in the Life of Sayyid Jalal al-din Bukhari Makhdum-i JahaniyanNo ratings yet

- Caesarean Moon Births: Calculations, Moon Sighting, and the Prophetic WayFrom EverandCaesarean Moon Births: Calculations, Moon Sighting, and the Prophetic WayNo ratings yet

- The Tranquil Soul: Practical Steps for Achieving Happiness and SuccessFrom EverandThe Tranquil Soul: Practical Steps for Achieving Happiness and SuccessNo ratings yet

- Preaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptFrom EverandPreaching Islamic Renewal: Religious Authority and Media in Contemporary EgyptNo ratings yet

- Authenticity And Islamic Liberalism: A Mature Vision Of Islamic Liberalism Grounded In The QuranFrom EverandAuthenticity And Islamic Liberalism: A Mature Vision Of Islamic Liberalism Grounded In The QuranNo ratings yet

- Islam: Between Divine Message and HistoryFrom EverandIslam: Between Divine Message and HistoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Meaning of Surah 24 An-Nur The Light (La Luz) From Holy Quran (El Sagrado Corán) Bilingual Edition English SpanishFrom EverandThe Meaning of Surah 24 An-Nur The Light (La Luz) From Holy Quran (El Sagrado Corán) Bilingual Edition English SpanishNo ratings yet

- The Illumination on Abandoning Self-Direction, Al-Tanwir fi Isqat Al-TadbirFrom EverandThe Illumination on Abandoning Self-Direction, Al-Tanwir fi Isqat Al-TadbirRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Divine System: The Quran and Islam a Progressive ViewFrom EverandThe Divine System: The Quran and Islam a Progressive ViewNo ratings yet

- Sufi Meditation Muraqaba StepByStepDocument10 pagesSufi Meditation Muraqaba StepByStepkarkunnomore86% (7)

- Theoretical Gnosis and Doctrinal SufismDocument35 pagesTheoretical Gnosis and Doctrinal Sufismruilov100% (5)

- CORBIN MeethingpointDocument7 pagesCORBIN MeethingpointFrancesco VinciguerraNo ratings yet

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr Sufism and The Perennity of The Mystical QuestDocument14 pagesSeyyed Hossein Nasr Sufism and The Perennity of The Mystical Questdr_xNo ratings yet

- Masnavi b4Document43 pagesMasnavi b4Mohammed Abdul Hafeez, B.Com., Hyderabad, IndiaNo ratings yet

- The Basic Structure of Metaphysical Thinking in IslamToshiko IzutsuDocument15 pagesThe Basic Structure of Metaphysical Thinking in IslamToshiko IzutsualakamasadaNo ratings yet

- The Sufi's Spiritual CourseDocument9 pagesThe Sufi's Spiritual CourseShaikh Mohammad Iqbal KNo ratings yet

- Rememberance of GodDocument21 pagesRememberance of GodBaquia100% (1)

- The Mystics of Islam Nichols 1921Document200 pagesThe Mystics of Islam Nichols 1921WaterwindNo ratings yet

- Hadith Qudsi Divine HadithsDocument156 pagesHadith Qudsi Divine Hadithshumarijan364No ratings yet

- Osman Yahya (Ibn Arabi) - Theophanies and Lights in The Thought of Ibn ArabiDocument8 pagesOsman Yahya (Ibn Arabi) - Theophanies and Lights in The Thought of Ibn ArabiQazim Ali SumarNo ratings yet

- Ibn Arabi On The Divine Love of BeautyDocument13 pagesIbn Arabi On The Divine Love of BeautySefwan AhmetNo ratings yet

- Morteza Tehrani - Sayyid Haydar Amuli An Overview of His Doctrines ThesisDocument161 pagesMorteza Tehrani - Sayyid Haydar Amuli An Overview of His Doctrines ThesisQazim Ali SumarNo ratings yet

- Khwajah Nasir Al Din Al Tusi - Awsaf Al Ashraf Attributes of The NobleDocument73 pagesKhwajah Nasir Al Din Al Tusi - Awsaf Al Ashraf Attributes of The NobleQazim Ali SumarNo ratings yet

- Ibn Arabi - Body of Light Account of The Death of His FatherDocument3 pagesIbn Arabi - Body of Light Account of The Death of His FatherQazim Ali SumarNo ratings yet

- Ibn Arabi - Futuhat 317 The Mi'Raj and Ibn 'Arabi's Own Spiritual Ascension and The IsraDocument58 pagesIbn Arabi - Futuhat 317 The Mi'Raj and Ibn 'Arabi's Own Spiritual Ascension and The IsraQazim Ali Sumar100% (2)

- John B Taylor - Ja'Far Al-Sadiq The Spiritual Forbearer of The Sufi'sDocument9 pagesJohn B Taylor - Ja'Far Al-Sadiq The Spiritual Forbearer of The Sufi'sQazim Ali SumarNo ratings yet

- Ibn 'Arabi and His Interpreters3 (34p) PDFDocument34 pagesIbn 'Arabi and His Interpreters3 (34p) PDFarslanahmedkhawajaNo ratings yet

- Ibn Arabi - Tarjuman Al-Ashwaq (Royal Asiatic Society, 1911)Document163 pagesIbn Arabi - Tarjuman Al-Ashwaq (Royal Asiatic Society, 1911)Sead100% (1)

- Ibn Arabi - Futuhat 317 The Mi'Raj and Ibn 'Arabi's Own Spiritual Ascension and The IsraDocument58 pagesIbn Arabi - Futuhat 317 The Mi'Raj and Ibn 'Arabi's Own Spiritual Ascension and The IsraQazim Ali Sumar100% (2)

- Ibn Arabi Book of Spiritual AdviceDocument15 pagesIbn Arabi Book of Spiritual AdviceEva WrightNo ratings yet

- Henry Corbin Theory of Visionary Knowledge in Islamic Philosophy Henry CorbinDocument14 pagesHenry Corbin Theory of Visionary Knowledge in Islamic Philosophy Henry CorbinQazim Ali Sumar100% (1)

- Henry Corbin - Chart of The ImaginalDocument8 pagesHenry Corbin - Chart of The ImaginalQazim Ali Sumar100% (5)

- L'Islâm Et La Voie de SunnaDocument160 pagesL'Islâm Et La Voie de SunnaMohamadou Ouattara DariNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2 KB 3 Modul 1Document22 pagesJurnal 2 KB 3 Modul 1ibu rapiahNo ratings yet

- Surah NotesDocument27 pagesSurah NotesAbdul Qayyum100% (1)

- Tema 2 GyhDocument6 pagesTema 2 GyhMariete RinconNo ratings yet

- Absen Sanlat 2023Document123 pagesAbsen Sanlat 2023kholikNo ratings yet

- Screenshot (2410)Document34 pagesScreenshot (2410)Prasanth mallavarapuNo ratings yet

- A Herança Árabe No Sul de PortugalDocument64 pagesA Herança Árabe No Sul de Portugalcmpcteixeira7782No ratings yet

- 2017 03 Cours Les IdrissidesDocument13 pages2017 03 Cours Les IdrissidesMimou ZeraNo ratings yet

- Fun Ramadan PacketDocument12 pagesFun Ramadan PacketSamiha Basyaib-Ammar2ANo ratings yet

- Tafseer-e-Naeemi 2 by - Hakeem-ul-Amamat Mufti Ahmad Yaar KhanDocument585 pagesTafseer-e-Naeemi 2 by - Hakeem-ul-Amamat Mufti Ahmad Yaar KhanMarfat Library100% (1)

- Story of The Ugly Man (Storytelling)Document2 pagesStory of The Ugly Man (Storytelling)salwa efendy100% (1)

- Al Huda Wan NoorDocument75 pagesAl Huda Wan NoorstrangurrkittensNo ratings yet

- Limiting Human Rights Task: Worksheet 39Document1 pageLimiting Human Rights Task: Worksheet 39Arvind RanganathanNo ratings yet

- Two Hijazi Fragments of The QuranDocument56 pagesTwo Hijazi Fragments of The QuranJaffer AbbasNo ratings yet

- Data Perkembangan Alumni EPS TOPIK 2013Document77 pagesData Perkembangan Alumni EPS TOPIK 2013Rodin Bina InsaniNo ratings yet

- My Dear Beloved Son (AL GHAZALI)Document46 pagesMy Dear Beloved Son (AL GHAZALI)mgs_pkNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Terbaru Genap Updte 311222Document12 pagesJadwal Terbaru Genap Updte 311222Ahmad Fuad RosyidiNo ratings yet

- Chap 6 Culture of PakistanDocument32 pagesChap 6 Culture of Pakistanusman ahmedNo ratings yet

- Symbole 2Document2 pagesSymbole 2Hadizatou DaoNo ratings yet

- Hijra BankDocument11 pagesHijra BankHassen0% (1)

- Ramadan Story TimeDocument5 pagesRamadan Story Timeapi-360426424No ratings yet

- Mughal HistoriographyDocument22 pagesMughal HistoriographySudhansu pandaNo ratings yet

- Histoire Du Maroc by Moi Et WikiDocument9 pagesHistoire Du Maroc by Moi Et WikiChou CheneNo ratings yet

- What Is WilayatDocument71 pagesWhat Is WilayatmeNo ratings yet

- The Teachings of A Sufi Master PDFDocument189 pagesThe Teachings of A Sufi Master PDFMarco Andreoni100% (2)

- Tema 3Document3 pagesTema 3María García Mateos Díaz-CachoNo ratings yet

- Data Induk Siswa TP 2017-2018Document80 pagesData Induk Siswa TP 2017-2018willyNo ratings yet

- Chorer Upor BatpariDocument8 pagesChorer Upor BatpariS.M.Nurul AnwarNo ratings yet

- E Unit Non Business Female MeritDocument8 pagesE Unit Non Business Female Meritmustainibneselim2002No ratings yet