Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aistotle Andplato

Uploaded by

Janica GaynorOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aistotle Andplato

Uploaded by

Janica GaynorCopyright:

Available Formats

Plato

Plato fell in with a wandering philosopher by the name of Socrates, of whom you may have heard, who encouraged

his students to challenge conventional wisdom to the point that he was finally executed in 399 BC for corrupting the

youth. This, Plato would say, was a major turning point in his life, and he fled Athens to avoid a similar fate by

association.

Truth with a capital T was abstract and eternal like numbers, which is to say it is immaterial and thus does not

experience degeneration, and everything in the world was an expression of this abstract Truth. Plato effectively

invented the word “perfection” as it is used today.

Plato also explains human existence in these terms, as humans are Good beings “fallen” from “the heavens” and

trapped in the lowest, most imperfect level of the Universe, which is the world he and you and I and all of us live in.

Plato believed that when a human being deduces or learns something they are in fact remembering something they

already know by virtue of our eternal, divine nature, which is why we are attracted to certain things in this world; we

recognize the Idea of “Goodness” in it from our time in the ether.

Thus, by denying our Passions with our Courage, which is governed by our Thinking (these three Plato believed to

be the three levels of human nature), we could dust off all our Divine knowledge and return to the heavens upon

death, avoiding another birth in the material world..

Aristotle

Aristotle was a scientist in the truest sense of his day and when good, scientific information was unavailable, he

insisted on strict logic. Relativism, or the belief that the Truth is whatever most people believe it to be, had created a

huge market for professional bullshit artists in Athens who instructed their students on how to effectively convince

crowds with sneaky and faulty arguments, a practice called Sophistry (now an insult of the first degree).

So unforgiving was Aristotle’s nose for BS that he invented the first formal system of logic in the West, still in use to

this day, which allows philosophical arguments to be written out as semi-mathematical formulas that can be easily

examined, evaluated, then accepted or dismissed, and boy did he dismiss.

Aristotle’s perfect man, consequently, does not deny his humanity the way Plato recommended; he perfects it.

In order for a man to perfect his humanity, he must be the best man he can be. To be his manly best, a man not only

needed to cultivate proper intentions and an appropriate disposition, but put those intentions into real virtuous action.

Aristotle called his hands-on form of constructive self-perfection eudaimonia, a word defined and redefined by

virtually every Greek thinker, coming from the Greek words for “good” or “well” (eu) and “spirit” or “soul”

(daimon).

Aristotle believed that all knowledge was accumulated memories, collected through a long series of observations and

connected by the mind into a single experience, like many pictures forming a single movie. Each picture leads into

the next, following a progression we make sense of in our minds, until we reach a logical conclusion. Having seen

certain actions lead to certain consequences before, an experienced man can see a particular picture and conclude

what will happen next. A man who can explain why one thing precedes the next thing and can invent an appropriate

conclusion, on the other hand, is wise according to Aristotle.

For example, an apprentice who knows that stacking blocks that were given to him in a specific order will produce

an arch is skilled and has experience. The master mason who knows that cutting blocks of that type stacked in that

order will always produce an arch and understands how the whole device works is virtuous, because he is artistic and

he possesses wisdom.

The pursuit of knowledge being a desirable and justified end in itself to Aristotle and the ancient Athenians in

general, the highest calling of men was therefore to amass wisdom, becoming greater and greater artists in their own

right through their ability to understand the universal application of knowledge (the “Why” and “How” of things)

over the simple, practical function of actions (the inglorious “What”).

In another in-your-face contradiction of Plato, Aristotle insisted this knowledge had to be learned through firsthand

experience – through observation with the senses and physical participation in the naturally perfect and good world –

and not by denying the physical world. Where Plato would say that one could uncover their innate knowledge of

how to play baseball by carefully reading a well-written book on the subject, Aristotle would reject the idea that

anyone was born knowing how to play baseball and that there is any other way to learn other than to get out on the

diamond, play the game, and create the new knowledge in your mind.

Why all this preoccupation with the kinesthetic nature of learning and knowledge? Because where Plato draws sharp

lines between the physical man and the rational, spiritual man, Aristotle sees no such distinction. Ever the scientist,

Aristotle saw the obvious leap of faith in Plato’s theories, in which a duality – or inherent double-nature – is

accepted on Plato’s word alone. Aristotle asserts that the physical and the rational are not two parts of men but two

dimensions of men. Thus, the exercise in good actions is as essential to the virtuous life as exercise in strength is to

the physically healthy life.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Essential BoydDocument14 pagesThe Essential Boydlewildale100% (3)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Analytical ReasoningDocument27 pagesAnalytical ReasoningWaqar VickyNo ratings yet

- PrepositionDocument23 pagesPrepositionMich Corpuz100% (4)

- PerDev Q1 Module-30-31Document30 pagesPerDev Q1 Module-30-31Kurt RempilloNo ratings yet

- Think-Pair or Group-ShareDocument10 pagesThink-Pair or Group-ShareKaren DellatanNo ratings yet

- Sensory - Based Reflection Sensory - Based Reflection: 1. What and Who Do I See? 1. What and Who Do I See?Document1 pageSensory - Based Reflection Sensory - Based Reflection: 1. What and Who Do I See? 1. What and Who Do I See?Janica GaynorNo ratings yet

- IT QuestionsDocument1 pageIT QuestionsJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Critical Evaluation in The Context of John RawlsDocument2 pagesChapter 1: Critical Evaluation in The Context of John RawlsJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- IT QuestionsDocument1 pageIT QuestionsJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Buddhism:: The Enlightened OneDocument7 pagesBuddhism:: The Enlightened OneJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Tibajia vs. Ca and Eden Tan G.R. No. 100290 June 4, 1993 FactsDocument3 pagesTibajia vs. Ca and Eden Tan G.R. No. 100290 June 4, 1993 FactsJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Formalization of Tasks: FALSE (Ans. Audit Trail)Document1 pageFormalization of Tasks: FALSE (Ans. Audit Trail)Janica GaynorNo ratings yet

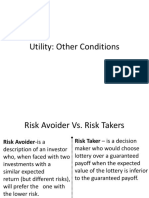

- 5 3utilityDocument2 pages5 3utilityJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Gaynor, Janica Teresa P. Bsma-Iv PHILO 106-C July 17, 2017: JustificationsDocument1 pageGaynor, Janica Teresa P. Bsma-Iv PHILO 106-C July 17, 2017: JustificationsJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Assistant DirectorDocument1 pageAssistant DirectorJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 4 SUMMARY (The Revenue Cycle)Document6 pagesCHAPTER 4 SUMMARY (The Revenue Cycle)Janica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Summary (The Expenditure Cycle Part I)Document11 pagesChapter 5 Summary (The Expenditure Cycle Part I)Janica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Footnote To Youth Is A Story Written by Jose Garcia VillaDocument2 pagesFootnote To Youth Is A Story Written by Jose Garcia VillaJanica GaynorNo ratings yet

- Using Predicate Logic: Representation of Simple Facts in LogicDocument10 pagesUsing Predicate Logic: Representation of Simple Facts in LogicAaa GamingNo ratings yet

- ADAMS (1991) Metaphors For Mankind The Development of Hans Blumenberg Anthropological MetaphorologyDocument16 pagesADAMS (1991) Metaphors For Mankind The Development of Hans Blumenberg Anthropological MetaphorologyDiego QuiñonesNo ratings yet

- Gerunds & Infinitives ChartDocument2 pagesGerunds & Infinitives ChartBlancaNo ratings yet

- 1949 Eysenck - Training in Clinical Psychology An English Point ofDocument4 pages1949 Eysenck - Training in Clinical Psychology An English Point ofyolanda sanchezNo ratings yet

- The Independence of Combinatory Semantic Processing: Evidence From Event-Related PotentialsDocument21 pagesThe Independence of Combinatory Semantic Processing: Evidence From Event-Related Potentialsdkm2030No ratings yet

- Hemachandra Yelishala Operations OB AssignmentDocument4 pagesHemachandra Yelishala Operations OB Assignmenthemachandra12No ratings yet

- In C1 Cte Sol J 19Document4 pagesIn C1 Cte Sol J 19Beatriz100% (1)

- DLP With VMC IntegrationDocument3 pagesDLP With VMC IntegrationJannet FuentesNo ratings yet

- A Seminar Report On Machine LearingDocument10 pagesA Seminar Report On Machine Learingali purityNo ratings yet

- Effects of Demotivation On Employee Performance in An OrganizationDocument2 pagesEffects of Demotivation On Employee Performance in An OrganizationDeo KaluleNo ratings yet

- OB Assignment PersonalityDocument2 pagesOB Assignment Personalityaysh_345No ratings yet

- Magic Mirror Table For Social Emotion Aleviation For The Smart HomeDocument19 pagesMagic Mirror Table For Social Emotion Aleviation For The Smart HomeNikhil PendyalaNo ratings yet

- Noun Phrase PDFDocument6 pagesNoun Phrase PDFhoifishNo ratings yet

- The Factors Affecting SHS TVL GraduatesDocument6 pagesThe Factors Affecting SHS TVL GraduatesAlvin ManodonNo ratings yet

- Paths To Mastery Lesson 17 Speaking Tips From Dale Carnegie The Quick and Easy Way To Effective SpeakingDocument10 pagesPaths To Mastery Lesson 17 Speaking Tips From Dale Carnegie The Quick and Easy Way To Effective SpeakingZelic NguyenNo ratings yet

- Agri - Crop 12 DLPDocument2 pagesAgri - Crop 12 DLPEden SumilayNo ratings yet

- Leadership StylesDocument5 pagesLeadership Styleskasandra gervinNo ratings yet

- Psicolinguistica ScoveDocument20 pagesPsicolinguistica ScoveFrancisco Sebastian KenigNo ratings yet

- INB490 FINAL AssignmentDocument7 pagesINB490 FINAL AssignmentMd. Shafiqul Haque BhuiyanNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Cultural Psychology Third EditionDocument12 pagesTest Bank For Cultural Psychology Third EditionCory Spencer100% (28)

- 545 5 - Roadmap B1. Teacher's Book 2019, 255p (1) - 39-50Document12 pages545 5 - Roadmap B1. Teacher's Book 2019, 255p (1) - 39-50fanaaNo ratings yet

- Definition of SBD Chapter 1Document16 pagesDefinition of SBD Chapter 1Marcky BoyNo ratings yet

- Penataran Pentaksiran pt3 CefrDocument26 pagesPenataran Pentaksiran pt3 CefrMiera Miji100% (1)

- Chopice IbodDocument3 pagesChopice Ibodemmanuel cresciniNo ratings yet

- Understanding Rhetorical SituationsDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Rhetorical SituationsMICHAELINA MARCUSNo ratings yet