Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journal Pone 0030248

Uploaded by

Putu Dessy Dian UtamiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal Pone 0030248

Uploaded by

Putu Dessy Dian UtamiCopyright:

Available Formats

Massage Therapy for Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A

Randomized Dose-Finding Trial

Adam I. Perlman1*, Ather Ali2, Valentine Yanchou Njike2, David Hom3,4, Anna Davidi2, Susan Gould-

Fogerite4, Carl Milak4, David L. Katz2

1 Duke Integrative Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, United States of America, 2 Prevention Research Center, Yale University School

of Medicine, Derby, Connecticut, United States of America, 3 Clinical Trials Unit, Section of Infectious Diseases, Boston Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, United

States of America, 4 School of Health Related Professions, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, Newark, New Jersey, United States of America

Abstract

Background: In a previous trial of massage for osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee, we demonstrated feasibility, safety and

possible efficacy, with benefits that persisted at least 8 weeks beyond treatment termination.

Methods: We performed a RCT to identify the optimal dose of massage within an 8-week treatment regimen and to further

examine durability of response. Participants were 125 adults with OA of the knee, randomized to one of four 8-week

regimens of a standardized Swedish massage regimen (30 or 60 min weekly or biweekly) or to a Usual Care control.

Outcomes included the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC), visual analog pain scale, range

of motion, and time to walk 50 feet, assessed at baseline, 8-, 16-, and 24-weeks.

Results: WOMAC Global scores improved significantly (24.0 points, 95% CI ranged from 15.3–32.7) in the 60-minute

massage groups compared to Usual Care (6.3 points, 95% CI 0.1–12.8) at the primary endpoint of 8-weeks. WOMAC

subscales of pain and functionality, as well as the visual analog pain scale also demonstrated significant improvements in

the 60-minute doses compared to usual care. No significant differences were seen in range of motion at 8-weeks, and no

significant effects were seen in any outcome measure at 24-weeks compared to usual care. A dose-response curve based on

WOMAC Global scores shows increasing effect with greater total time of massage, but with a plateau at the 60-minute/week

dose.

Conclusion: Given the superior convenience of a once-weekly protocol, cost savings, and consistency with a typical real-

world massage protocol, the 60-minute once weekly dose was determined to be optimal, establishing a standard for future

trials.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00970008

Citation: Perlman AI, Ali A, Njike VY, Hom D, Davidi A, et al. (2012) Massage Therapy for Osteoarthritis of the Knee: A Randomized Dose-Finding Trial. PLoS

ONE 7(2): e30248. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248

Editor: Ulrich Thiem, Marienhospital Herne - University of Bochum, Germany

Received July 25, 2011; Accepted December 14, 2011; Published February 8, 2012

Copyright: ß 2012 Perlman et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits

unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Funding: This publication was made possible by grant number R01 AT004623 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM)

at the National Institutes of Health. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCCAM. The

funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

* E-mail: adam.perlman@duke.edu

Introduction cardiac toxicity, as well as the removal of additional COX-2

inhibitors from the market, have lessened the public’s confidence

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a slowly progressive degenerative disease in pharmaceuticals and led to increased interest in therapeutic

of the joints that at present afflicts approximately 27 million interventions believed to be safer [12,13,14].

Americans [1,2]. With the aging of the ‘‘baby boom’’ population Massage therapy and certain other complementary and

and increasing rates of obesity, the prevalence of OA is estimated alternative medicine (CAM) interventions are being utilized by

to increase 40% by 2025 [3]. Conventional therapies for OA have OA sufferers, and represent attractive, potentially effective options

limited effectiveness, and toxicities associated with suitable drugs to manage pain [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Massage is one of the

thus often limit utilization, leaving many facing surgery or chronic, most popular CAM therapies in the US [14]. Between 2002 and

often debilitating, pain, muscle weakness, lack of stamina, and loss 2007, the 1-year prevalence of use of massage by the US adult

of function [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. In 2005, US costs from OA related population increased from 5% (10.05 million) to 8.3% (18.07

absenteeism alone were estimated at $10.3 billion, and in 2007, million) [14]. Massage is generally used to relieve pain from

OA increased aggregate annual medical care expenditures by musculoskeletal disorders [19,20,21,22], cancer, and other condi-

$185.5 billion (in 2007 dollars) [11]. Well-publicized events such as tions; rehabilitate sports injuries; reduce stress; increase relaxation;

the multiple lawsuits associated with rofecoxib and potential decrease feelings of anxiety and depression; and aid general

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 1 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

wellness [12,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Howev- Those passing telephone screening (n = 125), agreeing to the

er, only a relatively small body of research exists exploring the study protocol, and providing a written physician confirmation of

efficacy of massage therapy for any condition. OA were scheduled for an on-site evaluation to provide written

In 2006, we reported results of a pilot study of massage therapy informed consent and undergo clinical eligibility screening. All

for OA of the knee [18]. Subjects with OA of the knee meeting subjects received nominal compensation (consisting of gift

American College of Rheumatology Criteria [36] were random- certificates for future massages) for their participation. The

ized to biweekly (4 weeks), then weekly (4 weeks) Swedish massage intervention was delivered at two sites; St. Barnabas Ambulatory

(1 hour sessions) or wait list. Subjects receiving massage therapy Care Center (Livingston, NJ), and the Integrative Medicine Center

demonstrated significant improvements in the Western Ontario at Griffin Hospital (Derby, CT). Subject participation and flow are

and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) shown in Figure 1.

[37,38,39] pain, stiffness, and physical functional disability Recruitment and screening commenced in July 2009 in

domains (p,0.001) and visual analog pain scale [39] (p,0.01) Livingston, New Jersey and Southern Connecticut through flyers,

[18], compared to usual care. Notably, the benefits persisted up to newspaper advertisements, and press releases. Information letters

8 weeks following the cessation of massage [40]. Despite these were sent to patients identified with OA, as well as physicians in

promising results, there was no data to determine whether the dose the rheumatology and internal medicine practices at Saint

utilized in the pilot study was optimal. Barnabas Medical Center (Livingston, NJ) and Griffin Hospital

Here, we report the results of our Phase 2 dose-finding study to (Derby, CT). Of the 430 persons screened for eligibility, 168 did

identify a dose and treatment regimen of an 8-week course of a not meet eligibility criteria, 43 refused to participate, and 94 were

standardized Swedish massage therapy for OA of the knee that is not screened for other reasons (Figure 1). The most common

both optimal (providing greatest effectiveness) and practical reasons for ineligibility were 1) no documented confirmation of

(minimizing patient cost and inconvenience). To our knowledge, OA of the knee, 2) recent history of cortisone and hyaluronate

this was the first dose-finding study of massage therapy for OA, injections, and 3) history of knee replacement. Enrollment

and for OA of the knee specifically. This trial employed a more continued until July 2010. 125 subjects were randomized to

diverse subject population at two clinical sites, and assessed longer- receive one of four active massage arms (Groups 1–4) and one

term residual effects, than did our earlier pilot study. In addition, a Usual Care/control arm.

formally manualized massage protocol was developed and utilized

[18]. Results of the trial reported herein will inform the dosing Randomization

regimen for future clinical trials designed to confirm the efficacy of Participants were block randomized using a permuted block

massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee and define its place design (blocks of 5 or 10) in a 1:1:1:1:1 ratio and stratified by site

in clinical practice. and body mass index (BMI) to ensure balance between the

intervention and Usual Care groups across the two performance

Methods sites.. The study statistician (VYN) generated the random

allocation sequence using SAS Software version 9.1. Each eligible

The protocol for this trial and supporting CONSORT checklist are and consented subject (identified by number) was assigned to one

available as supporting information; see Checklist S1 and Protocol S1. of the treatment arms. Treatment allocation was only known by

the statistician and the study assistants (CM and AD) that assigned

Ethics Statement participants to interventions and generated visit schedules.

The study protocol, consent form and all recruitment materials

were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Study Design and Interventions

University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (Newark, This study was a randomized clinical trial with four treatment

NJ), Griffin Hospital (Derby, CT), and the Saint Barnabas Medical arms (and one Usual Care arm) designed to assess the effects of 8

Center (Livingston, NJ). The study was conducted in accordance weeks of a standardized Swedish massage protocol (see Manualiza-

with the Declaration of Helsinki. tion) provided at four distinct doses (Figure 1). Group 1 received

30 minutes of massage weekly for eight weeks. Group 2 received

Participants 30 minutes of massage twice weekly for the initial four weeks, and

Eligible patients were men and women with radiographically- once weekly for the remaining four weeks. Group 3 received

established OA of the knee who met American College of 60 minutes of massage weekly for eight weeks. Group 4 received

Rheumatology criteria [36], were at least 35 years of age, and had 60 minutes of massage twice weekly for the initial four weeks, and

a pre-randomization score of 40 to 90 on the visual analog pain once weekly for the remaining four weeks. Group 4 received the

scale. Patients with bilateral knee involvement had the more same dosing regimen as was given in our pilot trial [41]. The

severely affected knee (determined by the patient) designated as Usual Care group continued with their current treatment without

the study knee. Subjects using NSAIDS or other medications to the addition of massage therapy.

control pain were included if their doses remained stable three The doses were chosen as practical regimens that are commonly

months prior to starting the intervention. used in massage therapy and were designed to investigate the

Subjects were excluded if they suffered from rheumatoid variables of length of individual treatment (30 min vs. 60 min),

arthritis, fibromyalgia, recurrent or active pseudogout, cancer, or frequency (weekly vs. twice weekly), and total treatment time

other serious medical conditions. Subjects were also excluded if (240 min (Group 1, 30 min weekly68 wk), 360 min (Group 2,

they had signs or history of kidney or liver failure; unstable asthma; 30 min biweekly64 wk+30 min weekly64 wk), 480 min (Group

knee replacement of both knees; reported recent use (4 weeks–1 3, 60 min weekly68 wk), or 720 min (Group 4, 60 min biweek-

year prior to enrollment) of oral or intra-articular corticosteroids ly64 wk+60 min weekly64 wk)).

or intra-articular hyaluronate; or knee arthroscopy or significant

knee injury one year prior to enrollment. A rash or open wound Manualization

over the knee and regular use of massage therapy (greater than Prior to enrolling subjects, a formal manualization process

once a month) also resulted in exclusion from the study. produced a study protocol that was tailored to subjects with OA of

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 2 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

Figure 1. Participant Flow Diagram.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248.g001

the knee, while respectful of the individualized nature of massage quantitative assessment of OA of the knee, and has been proven

therapy [42]. The manualization process, conducted over the to be effective in assessing pain in those suffering from the illness

course of two months, involved the input of licensed massage [37,38,44]. It assesses dimensions of pain, functionality and joint

therapists that participated in the pilot study, massage researchers, stiffness through 24 questions. The WOMAC has been subject to

as well as the investigative team. The resulting massage protocol numerous validation studies to assess reliability and responsiveness

was made reproducible, using standard massage techniques to change in therapy, including physical forms of therapy

[18,43], as well as flexible for individual subject variability. [37,38,44] and was successfully utilized in the Phase 1 study [18].

The manualized protocol specifies the body regions to be

addressed; with distinct 30 and 60-minute protocols (Table 1), as Secondary outcome measures

well as the standard Swedish strokes to be used (effleurage, Secondary measures included pain as measured on a visual

petrissage, tapotement, vibration, friction, and skin rolling) [18]. analog scale (0 to 100 scale), a validated [39] mechanical scale

Each protocol specifies the time allocated to various body regions used to measure pain sensation intensity evoked by nociceptive

(lower/upper limbs, lower/upper back, head, neck, chest). The stimuli [45]. Other secondary outcomes were joint flexibility,

protocol was specifically designed to address symptoms of defined as the range of motion (ROM) allowed at the knee during

osteoarthritis of the knee. The order of body regions is not flexion using a double-armed goniometer, and measured time to

specified in order to account for individual practitioner preference. walk 50 feet (15 m) on a level surface within the clinic facilities.

The manual specifies intentions/attentions for the study massage Outcomes were assessed at baseline, 8-weeks, 16-weeks, and 24-

therapists. Each study therapist was taught and agreed to the weeks post-baseline. Assessment visits were scheduled by a

protocol and signed a form attesting to adherence to the study research assistant, though the measurements were assessed by

protocol after each massage session. Study personnel reviewed separate personnel blinded to treatment assignments. Adherence

adherence to the protocol at regular intervals throughout the study was assessed by tracking the number of massage visits that subjects

period. No deviations from the manualized massage protocol completed.

occurred.

Statistical Analysis

Primary outcome measure Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS software (Version

The primary outcome measure was change in the Western 9.1, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Repeated measures ANOVA using

Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC– linear mixed model regression was used to determine between-

Global). The WOMAC has been used extensively in the group changes in all outcome measures and changes in domain-

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 3 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

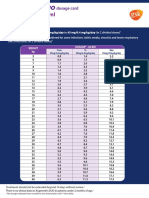

Table 1. 30- and 60-Minute Massage Protocols.

30 minute protocol (25 minutes of table time)

Region Time Allotted Distribution

Lower Limbs 12–15 min (45–50% of session) From knee down including lower leg, ankle, and foot. From knee up

including hips, pelvis, buttocks & thigh.

Upper Body 8–12 min (36–44% of session) Lower and upper back. Head/Neck/Chest

Discretionary 2–5 min (6–19% of session) Therapist to expand treatment to other affected areas; i.e. rib cage, flank,

upper limbs, etc.

60 minute protocol (55 minutes of table time*)

Lower Limbs 20–27.5 min (45–50% of session) From knee down including lower leg, ankle, and foot. From knee up

including hips, pelvis, buttocks and thigh.

Upper Body 15–24 min (36–44% of session) Lower and upper back. Head, neck, and chest.

Discretionary 3.5–20 min (6–19% of session) Therapist to expand treatment to other affected areas; i.e. rib cage, flank,

upper limbs, etc.

*Accounting for time spent in transition including the welcome, transition to the massage room, taking off jewelry, and other preparatory activities.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248.t001

specific (i.e. pain, stiffness, and functionality) WOMAC measures, massage (Groups 2, 3 and 4), whereas no improvement (p.0.05)

controlling for time-dependent variables. In all analyses, a two- in Usual Care was seen at any time point (Tables 3 and 4).

tailed a of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Duncan’s multiple range test (a multiple comparison test) was used WOMAC Stiffness Subscale

to determine whether means differ significantly across treatment No significant between-group changes were seen in WOMAC

groups. A dose-response curve was plotted assessing the magnitude Stiffness, though the magnitude of change was greater in all

of improvement on 8-week WOMAC Global scores plotted treatment groups compared to usual care.

against the total 8-week dose of massage. A sample size of 125

individuals in five arms was based on budgetary and logistical WOMAC Functionality Subscale

constraints. The 60-minute doses (Groups 3 and 4) were significantly (21.2–

22.0 points, 95% CI ranged from 12.5–31.6 points) improved

Results compared to usual care (6.6 points, 95% CI ranged from 0.9–12.2)

at 8-weeks (Table 3).

Of the 125 enrolled subjects, 119 completed the 8-week

assessment and 115 completed the entire trial (Figure 1). Subjects

Dose Response

received the intervention between November 2009 and October A dose-response curve based on changes in WOMAC Global

2010. scores at 8-weeks shows increasing effect with greater total time of

Baseline characteristics of the study participants are provided in massage, but with a plateau at the 480-minute dose (Group 3)

Table 2. The randomization process with stratification by BMI (Figure 2).

was largely successful in producing equivalent groups. The only

differences seen at baseline were that Group 1 was older than the

Visual Analog Pain Scale

other groups, and Group 3 had more perceived pain than usual Pain perception improved significantly (31.2–39.8 points, 95%

care as assessed by the visual analog scale, though no differences CI ranged from 22.9–48.1 points) in both 60-minute dose groups

were seen in the pain subscale of the WOMAC. (Groups 3 and 4) compared to Usual Care at 8-weeks post

baseline, with no significant differences between Groups 3 and 4.

Primary Outcome All treatment groups reported decreased pain perception com-

WOMAC Global scores improved significantly (24.0 points, pared to baseline at all time points (Tables 3 and 4).

95% CI ranged from 15.3–32.7) in the 60-minute massage groups

compared to Usual Care (6.3 points, 95% CI 0.1–12.8) at the Timed 50-foot walk

primary endpoint of 8-weeks (Table 3). No statistically significant All groups showed decreased time to walk 50 feet at all time

differences between the massage groups were detected at 8 weeks, points, except group 1 at week 8 (Tables 3 and 4). However, there

though the magnitude of change in the groups receiving 60-minute were no significant differences between the groups at any

doses (Groups 3 and 4) was greater than the magnitude of change timepoint.

in the groups receiving 30-minute doses (Groups 1 and 2) (Table 3).

Range of Motion

WOMAC Pain Subscale No significant between-group differences were seen in range of

The 60-minute doses (Groups 3 and 4) were also significantly motion at 8-weeks post-baseline, though all massage groups

(27.2–27.7 points, 95% CI ranged from 18.0–36.9 points) im- changed in the positive direction. Group 4, the highest total dose

proved compared to usual care (5.6 points, 95% CI ranged from of massage, was significantly improved from baseline at all time

21.9–13.1) at 8-weeks (Table 3). Significant improvement points. The 30-minute protocols and Usual Care groups did not

(p,0.05) from baseline was achieved for all massage groups at 8 demonstrate any significant changes from baseline at any

weeks, and at 16 and 24 weeks for the three highest doses of timepoint.

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 4 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

Table 2. Demographic Characteristics and Baseline Values.

Variable Group 1 (n = 25) Group 2 (n = 25) Group 3 (n = 25) Group 4 (n = 25) Usual Care (n = 25)

Gender

Female 15 (12.0%) 18 (14.4%) 19 (15.2%) 17 (13.6%) 19 (15.2%)

Male 10 (8.0%) 7 (5.6%) 6 (4.8%) 8 (6.4%) 6 (4.8%)

Race

White 23 (18.4%) 22 (17.6%) 19 (15.2%) 20 (16.0%) 22 (17.6%)

Asian 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.8%) 0 (0.0%)

White/Asian 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.8%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%)

African American 2 (1.6%) 2 (1.6%) 4 (3.2%) 4 (3.2%) 2 (1.6%)

Hispanic 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.8%) 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%)

Unknown 0 (0.0%) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.8) 0 (0.0%) 1 (0.8%)

Age (years) 69.968.6 61.969.5 62.6610.6 63.6613.0 63.6610.2

Body Mass Index (kg/m2) 31.067.5 32.166.8 31.866.7 31.367.1 31.766.5

WOMAC (mm)

Pain 52.3619.9 42.4623.0 52.5616.5 44.4619.3 46.3615.4

Stiffness 53.4624.1 58.6621.1 58.4624.7 51.2624.4 62.8618.2

Functionality 52.9617.9 49.5619.5 49.8619.7 48.3620.2 50.5617.4

Global 52.9618.3 50.2619.4 53.6617.3 48.0619.0 53.2614.8

Pain (VAS) (mm) 61.2616.8 64.0612.7 66.4611.3 59.2613.3 57.669.0

50-foot walk (seconds) 18.366.9 16.867.0 15.663.2 15.765.4 15.762.8

Range of Motion (degrees) 108.7614.6 114.4610.4 115.3610.5 112.8612.6 115.669.6

Values are mean 6 SD except otherwise stated.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248.t002

Adherence Discussion

Subjects completing 80% or more of assigned visits (8 or 12

This was the first formal dose-finding study of massage therapy

visits, based on treatment assignment) were considered adherent;

for any condition. This study investigated four different doses of

119/125 subjects were adherent to all assigned massage visits with

tailored Swedish massage, varying both the time (30 vs.

no significant differences in adherence between treatment

60 minutes per treatment) and frequency (once a week vs. twice

assignments (Figure 1).

a week for the first month) to determine an optimal, practical dose

to use in future studies. Our manualized protocol incorporated

Adverse Effects standard Swedish massage techniques focused on osteoarthritis of

No adverse effects related to the intervention were seen during the knee, based on the protocol used in our Phase 1 study. We

the course of the study. operationally defined ‘optimal-practical’ as ‘producing the greatest

Table 3. Mean change (95% CI) in outcomes at 8-weeks post-baseline (primary endpoint).

GROUP (n) Group 1 (n = 22) Group 2 (n = 24) Group 3 (n = 24) Group 4 (n = 25) Usual Care (n = 24)

DOSE 30 min 16/wk 30 min 26/wk 60 min 16/wk 60 min 26/wk (no massage)

TOTAL MASSAGE RECEIVED 240 min 360 min 480 min 720 min 0 min

WOMAC (mm)

Pain 215.1 (223.4, 26.8) 214.4 (223.8, 25.1) 227.2 (236.3, 218.0){ 227.7 (236.9, 218.6){ 25.6 (213.1, 1.9)

Stiffness 219.0 (230.4, 27.6) 223.4 (234.5, 212.3) 223.7 (234.6, 212.7) 222.3 (232.9, 211.6) 26.7 (215.7, 2.2)

Functionality 218.0 (225.5, 210.4) 217.2 (226.9, 27.6) 221.2 (229.3, 213.1){ 222.0 (231.6, 212.5){ 26.6 (212.2, 20.9)

Global 217.4 (225.3, 29.4) 218.4 (227.5, 29.2) 224.0 (232.1, 215.9){ 224.0 (232.7, 215.3){ 26.3 (212.8, 0.1)

Visual Analog Scale (mm) 214.2 (225.0, 23.4) 226.1 (236.8, 215.3) 239.8 (248.1, 231.4){{ 231.2 (239.4, 222.9){ 29.8 (218.6, 21.1)

50-foot walk (seconds) 21.3 (23.0, 0.4) 22.4 (24.7, 20.1) 21.7 (22.7, 20.6) 22.0 (23.4, 20.6) 21.3 (22.4, 20.2)

Range of Motion (degrees) 22.5 (27.5, 2.6) 24.8 (29.9, 0.4) 21.3 (26.2, 3.5) 26.6 (211.6, 21.6) 0.2 (24.1, 4.4)

Values are mean with 95% confidence intervals; negative values indicate improvement;

{

Significant (non-overlap) compared to Usual Care;

{

Significant (non-overlap) compared to Group 1.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248.t003

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 5 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

Table 4. Changes in outcomes at 24-weeks post-baseline.

GROUP (n) Group 1 (n = 22) Group 2 (n = 24) Group 3 (n = 24) Group 4 (n = 25) Usual Care (n = 24)

DOSE 30 min 16/wk 30 min 26/wk 60 min 16/wk 60 min 26/wk (no massage)

WOMAC (mm)

Pain 212.2 (222.4, 22.0) 23.9 (212.7, 4.9) 213.7 (223.4, 24.0) 214.2 (224.5, 23.8) 27.5 (216.0, 1.1)

Stiffness 215.4 (226.4, 24.5) 29.6 (220.6, 1.3) 216.9 (228.5, 25.2) 216.8 (229.7, 23.9) 26.4 (213.2, 0.4)

Functionality 215.3 (224.5, 26.1) 27.4 (214.8, 0) 212.1 (222.0, 22.1) 214.4 (223.4, 25.4) 24.2 (211.1, 2.7)

Global 214.3 (222.9, 25.7) 27.0 (215.6, 1.6) 214.2 (223.4, 25.0) 215.1 (225.1, 25.1) 26.0 (212.6, 0.5)

Visual Analog Scale (mm) 214.4 (225.9, 22.8) 214.0 (224.7, 23.3) 218.5 (229.0, 28.1) 222.8 (235.5, 210.1) 211.5 (221.0, 22.0)

Time to walk 50 Feet (seconds) 22.4 (24.4, 20.4) 21.8 (23.6, 0) 21.4 (22.8, 0) 21.8 (23.3, 20.3) 21.4 (22.6, 20.2)

Range of Motion (degrees) 24.76(210.9, 1.5) 0.4 (25.7, 4.8) 22.7 (27.6, 2.3) 28.3 (214.2, 22.5) 20.3 (24.7, 4.1)

Values are mean with 95% confidence intervals; negative values indicate improvement.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248.t004

ratio of desired effect compared to costs (in time, labor, and in WOMAC Global scores at the termination of massage (8-week

convenience).’ If the most effective dose were the least labor- timepoint). In addition, all massage groups reported significantly

intensive, ‘optimal’ and ‘optimal-practical’ would be the same. decreased WOMAC Pain as assessed by VAS at the 8-week

We were also interested in seeing whether the promising results timepoint compared to baseline, which was also different from

of our pilot study would be repeated and extended with this now usual care for the three highest doses.

manualized protocol of Swedish massage, with a more diverse Angst et. al estimated minimal clinically important differences

population at two sites, with a longer follow up period. The (MCID) in WOMAC global scores (for improvement) to be 18%

potential effectiveness of this treatment was further supported in change from baseline [46], while Escobar et al. found that a

this study, as all massage doses demonstrated significant MCID is approximately 15 points in patients following total knee

improvement from baseline, as well as differences from usual care replacement [47]. In our study, subjects receiving the 60-minute

Figure 2. Dose-Response Curve. Dose-response curve plotting dose (total minutes over the course of 8-weeks of massage) (x-axis) vs.

improvement (change in WOMAC Global scores after 8-weeks). Dose-response effects plateaued at 480-minutes (Group 3), with no significant

improvements noted in the 720-minute (Group 4) dose.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248.g002

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 6 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

doses improved a mean of 24.0 points in WOMAC global scores There is some evidence for the promotion of a relaxation response

(44%–50% change from baseline). Thus, the magnitude of change and shift to parasympathetic nervous system activation, with

in WOMAC scores is highly clinically significant. reduced heart rate, blood pressure, biochemical, (including blood

Our results suggest a benefit of increasing massage dose with and salivary stress hormones, endorphins, and serotonin), and

diminishing returns at the highest level. Our dose-response curve brain activation changes, associated with reduced anxiety

based on WOMAC Global scores indicates increasing improve- [40,54,55,56,57,58,59]. This may be mediated through the

ment with greater total dose (minutes) of massage, with a threshold activation of mechanoreceptors in the deep tissues innervated by

effect at the 480-minute dose (Group 3). While it is difficult to tease alpha beta fibers with subsequent central nervous system (CNS)

out differences due to total dose and effectiveness of 30 vs. effects on the pituitary gland and limbic system and/or other

60 minute individual treatments, due to the design of the study, mechanisms [60]. The need for moderate pressure to achieve

there is a clear trend for greater magnitude of changes in our many of the effects of massage therapy may support this

outcomes in both of the 60-minute doses (Groups 3 and 4), mechanism, deserves further investigation, and supports light

compared to baseline, usual care, and the 30-minute dose groups. touch as an appropriate active control for future trials

There were no significant differences when comparing the 60- [25,51,55,58,61,62]. A recent study comparing a single session

minute groups to each other at any time point or for any outcome. of Swedish massage to light touch showed significant neuroendo-

WOMAC subscales generally followed the pattern of the global crine and immune system changes over time, with differing

scores, with strongest responses for the higher doses. patterns and degree in the massage and control intervention [59].

The durability of the response in improvement of OA symptoms Other potential outcomes and mechanisms of massage therapy’s

and functionality to massage treatment was also supported by the effectiveness include decreasing muscle strain, balancing muscle

results of this study. Our Phase 1 trial [18] demonstrated tension across the joint, positive mechanical changes in muscles,

significant effects of massage therapy 16-weeks post-baseline on increased joint flexibility and proprioception, increased lymphatic

the WOMAC, visual analog pain scale, and the 50-foot timed circulation, immunologic and inflammatory changes, improved

walk. Anticipating similar effects, we assessed subjects at 16 weeks sleep, and blocking pain signals [32,53,63,64,65,66,67]. Research

and extended our observations to 24-weeks post-baseline. dedicated to exploring the mechanisms of effect is clearly

Although the magnitude of effects was strongest after 8 weeks of warranted.

treatment and generally decreased with time, the persistence of Limitations of this trial included a small sample. Further, the

improvements at 2 months and 4 months after treatment cessation truly ‘‘optimal’’ dose might differ from any of the four studied.

indicate that the effects of the 8 weeks of massage go beyond Although additional doses for the massage intervention could have

immediate changes to longer term shifts that may be global and/or been considered, the regimens that were assessed conform well to

localized to the knee, suggesting that periodic maintenance doses massage regimens currently in use, are advocated by massage

of massage may help sustain effects over time. The mechanisms for therapists, and were practical to implement. Our trial was also

such persistent benefit are not fully elucidated, and clearly warrant limited to Swedish massage techniques. This limits generalizability

investigation. to other techniques, but offers the advantage of clear standard-

All massage groups demonstrated significant improvement in ization of the intervention. Swedish technique predominates in

WOMAC Global scores at 16 and 24 week timepoints compared clinical settings [68] and is thus the logical, initial choice; other

to baseline, whereas those in the usual care group did not massage techniques should be compared to Swedish massage once

(Figure 3). The three highest doses of massage improved relative to its efficacy is established. Further, the Swedish technique has been

baseline in WOMAC pain at 16 and 24 weeks, in stiffness at 24 successfully applied and demonstrated promise in our pilot study

weeks, and functionality at 16 and 24 weeks. [18].

All groups, including usual care, demonstrated decreases in the As the mechanism(s) of action of massage are not fully

timed 50-foot walk compared to baseline, but no clear patterns of elucidated, it is premature to predict dose-responses for higher

dose effect or significant differences between the groups. Larger or lower doses than the doses utilized in this trial, or applied to

groups and perhaps a 100-foot walk may be needed to detect clinical models besides osteoarthritis of the knee. For example, if

between-group differences. Although almost no statistically massage enhances regional blood flow, it might be that a follow-up

significant differences between the massage groups and Usual massage too soon (i.e. within one week) actually attenuates benefit

Care were seen in the 16 and 24 week time points, the by applying pressure to slightly engorged tissue. Thus, there might

directionality of all changes was towards improvement, and the be an optimal periodicity to massage, with suboptimal effects seen

magnitude of changes seen was greater than changes seen in Usual with dosing outside this purported ideal. Changes in neuroendo-

Care (Table 4). Our sample size was inadequate to determine crine and inflammatory status, pain generation and sensitivity, or

statistically significant between-group changes, as the goal for this musculature strain or balance, may also reach an optimal state,

Phase 2 trial was to determine an optimal-practical dose, rather which persists for some time, and is not enhanced by further

than to determine efficacy. massage within a weeks’ time. Our study, however, did not

Future studies should incorporate larger samples that adequate- attempt to establish a dose-response gradient. Rather, the goal was

ly power for between group changes in longer term effects of to establish an optimal-practical dose for future testing, based on

massage therapy. The improvements in the Usual Care arm in the combination of convenience, practicability, and therapeutic

some outcome measures, possibly due to Hawthorne [48] or other effectiveness.

nonspecific effects [49], reduced the magnitude of between-group

differences, and reaffirm the importance of control groups in this Conclusion

type of study. This dose-finding trial established an optimal dose of 60-

Massage is theorized to work through a variety of mechanisms. minutes of this manualized Swedish massage therapy treatment

Increased blood circulation to the muscles promoting gas delivered once weekly in an eight week protocol for OA of the

exchange and delivery of nutrients and removal of waste products knee. This decision was based on the superiority of the 60 minute

has long been thought to be one of the outcomes and benefits of compared to 30 minute treatments, the essentially equivalent

massage, and recent studies support this effect [50,51,52,53]. outcomes of the two 60 minute doses, the convenience of a once-

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 7 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

Figure 3. Improvement in WOMAC-Global Scores at Assigned Doses of Massage.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030248.g003

weekly protocol (compared to biweekly), cost savings, and Protocol S1 Trial Protocol.

consistency with a typical real-world massage protocol. As there (PDF)

is promising [18], but not definite [69], potential for the utility of

massage therapy for knee osteoarthritis, future research on this Acknowledgments

standardized approach to massage therapy should utilize this dose.

In addition, future, more definitive research is needed investigating We thank the study subjects for their participation. Licensed massage

therapists Linda Winz, Michael Yablonsky, Susan Kmon, and Lee Stang

not only the efficacy, but also cost-effectiveness of massage for OA

provided massages for study subjects. Mary Carola, Margaret Rogers, Beth

of the knee and other joints, as well as research exploring the Comerford and Dr. Lisa Rosenberger provided technical and administra-

mechanism(s) by which massage may exert its effects in this clinical tive support.

application and in general.

Author Contributions

Supporting Information

Conceived and designed the experiments: AP AA DH SGF DLK.

Checklist S1 CONSORT Checklist. Performed the experiments: AA AD CM. Analyzed the data: AP AA VYN

(DOC) SGF DLK. Wrote the paper: AP AA AD SGF DLK.

References

1. Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, et al. (2008) 14. Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL, Barnes PM, Bloom B, et al. (2008)

Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children:

United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 58: 26–35. United States, 2007. National health statistics reports. pp 1–23.

2. Arden N, Nevitt M (2006) Osteoarthritis:epidemiology. Best Pract Res Clin 15. Perlman A, Meng C (2003) Rheumatology. In: Leskowitz E, ed. Complementary

Rheumatol 20: 3–25. and Alternative Medicine in Rehabilitation. St. Louis: Harcourt Heath Sciences.

3. Matchaba P, Gitton X, Krammer G, Ehrsam E, Sloan VS, et al. (2005) pp 352–362.

Cardiovascular safety of lumiracoxib: A meta-analysis of all randomized 16. Perlman A, Spierer M (2003) Osteoarthritis. In: Rakel D, ed. Integrative

controlled trials 1 week and up to 1 year in duration of patients with Medicine. Orlando: W.B. Saunders Co. pp 414–422.

osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 27: 1196–1214. 17. Perlman A, Weisman R (2006) Own Your Own Health - The Best of Alternative

4. Kato T, Xiang Y, Nakamura H, Nishioka K (2004) Neoantigens in osteoarthritic and Conventional Medicine. Pain Deerfield BeachFL: Health Communications,

cartilage. Curr Opinion Rheumatol 16: 604–608. Inc.

5. Fisher N, Pendergast D (1997) Reduced muscle function in patients with 18. Perlman AI, Sabina A, Williams AL, Njike VY, Katz DL (2006) Massage

osteoarthritis. Scand J Rehab Med 29: 213–221. therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern

6. Messier S, Loeser R, Hoover J, Semble E, Wse C (1992) Osteoarthritis of the Med 166: 2533–2538.

knee:Effects on gait, strength, and flexibility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 73: 29–36. 19. Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Deyo RA, Shekelle PG (2003) A review of the

7. Felson D (2004) An update on the pathogenesis and epidemiology of evidence for the effectiveness, safety, and cost of acupuncture, massage therapy,

osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin North Am 42: 1–9. and spinal manipulation for back pain. Ann Intern Med 138: 898–906.

8. Richmond J, Hunter D, Irrgang J, Jones MH, Levy B, et al. (2009) Treatment of 20. Preyde M (2000) Effectiveness of massage therapy for subacute low-back pain: A

osteoarthritis of the knee (nonarthroplasty). J Am Acad Orthop Surg 17: randomized controlled trial CMAJ 162: 1815–1820.

591–600. 21. Hernandez-Reif M, Field T, Krasnegor J, Theakston H (2001) Lower Back Pain

9. Hunter DJ, Felson DT (2006) Osteoarthritis. BMJ 332: 639–642. is Reduced and Range of Motion Increased After Massage Therapy.

10. Naesdal J, Brown K (2006) NSAID-associated adverse effects and acid control International Journal of Neuroscience 106: 131–145.

aids to prevent them: A review of current treatment options. Drug Saf 29: 22. Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Hawkes RJ, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA (2009)

119–132. Randomized trial of therapeutic massage for chronic neck pain. Clinical Journal

11. Kotlarz H, Gunnarsson CL, Fang H, Rizzo JA (2009) Insurer and out-of-pocket of Pain 25: 233–238.

costs of osteoarthritis in the US: evidence from national survey data. Arthritis 23. Wentworth LJ, Briese LJ, Timimi FK, Sanvick CL, Bartel DC, et al. (2009)

Rheum 60: 3546–3553. Massage therapy reduces tension, anxiety, and pain in patients awaiting invasive

12. Ernst E (2002) Complementary and alternative medicine for pain management cardiovascular procedures. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing 24: 155–161.

in rheumatic disease Curr Opin Rheum 14: 58–62. 24. Listing M, Reisshauer A, Krohn M, Voigt B, Tjahono G, et al. (2009) Massage

13. National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (2010) NCCAM therapy reduces physical discomfort and improves mood disturbances in women

Backgrounder: Massage Therapy: An Introduction. with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 18: 1290–1299.

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 8 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

Dose-Finding Study of Massage for Osteoarthritis

25. Kutner JS, Smith MC, Corbin L, Hemphill L, Benton K, et al. (2008) Massage 46. Angst F, Aeschlimann A, Michel BA, Stucki G (2002) Minimal clinically

therapy versus simple touch to improve pain and mood in patients with important rehabilitation effects in patients with osteoarthritis of the lower

advanced cancer: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine 149: extremities. J Rheumatol 29: 131–138.

369–379. 47. Escobar A, Quintana JM, Bilbao A, Arostegui I, Lafuente I, et al. (2007)

26. Jane S-W, Wilkie DJ, Gallucci BB, Beaton RD, Huang H-Y (2009) Effects of a Responsiveness and clinically important differences for the WOMAC and SF-36

full-body massage on pain intensity, anxiety, and physiological relaxation in after total knee replacement. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 15: 273–280.

Taiwanese patients with metastatic bone pain: a pilot study. Journal of Pain & 48. Bouchet C, Guillemin F, Briancon S (1996) Nonspecific effects in longitudinal

Symptom Management 37: 754–763. studies: impact on quality of life measures. J Clin Epidemiol 49: 15–20.

27. Frey Law LA, Evans S, Knudtson J, Nus S, Scholl K, et al. (2008) Massage 49. Kaptchuk TJ (1998) Powerful placebo: the dark side of the randomised

reduces pain perception and hyperalgesia in experimental muscle pain: a controlled trial. Lancet 351: 1722–1725.

randomized, controlled trial. Journal of Pain 9: 714–721. 50. Kirby BS, Carlson RE, Markwald RR, Voyles WF, Dinenno FA (2007)

28. Field T, Figueiredo B, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Deeds O, et al. (2008) Mechanical influences on skeletal muscle vascular tone in humans: insight into

Massage therapy reduces pain in pregnant women, alleviates prenatal depression contraction-induced rapid vasodilatation. J Physiol 583: 861–874.

in both parents and improves their relationships. Journal of Bodywork & 51. Sefton JM, Yarar C, Berry JW, Pascoe DD (2010) Therapeutic massage of the

Movement Therapies 12: 146–150. neck and shoulders produces changes in peripheral blood flow when assessed

29. Ezzo J, Haraldsson BG, Gross AR, Myers CD, Morien A, et al. (2007) Massage with dynamic infrared thermography. J Altern Complement Med 16: 723–732.

for mechanical neck disorders: a systematic review. Spine 32: 353–362. 52. Cambron JA, Dexheimer J, Coe P, Swenson R (2007) Side-effects of massage

30. Downey L, Diehr P, Standish LJ, Patrick DL, Kozak L, et al. (2009) Might therapy: a cross-sectional study of 100 clients. Journal of Alternative &

massage or guided meditation provide ‘‘means to a better end’’? Primary Complementary Medicine 13: 793–796.

outcomes from an efficacy trial with patients at the end of life. Journal of 53. Nayak S, Matheis R, Agostinelli S, Shifleft S (2001) The use of complementary

Palliative Care 25: 100–108. and alternative therapies for chronic pain following spinal cord injury: A pilot

31. Corbin LW, Mellis BK, Beaty BL, Kutner JS (2009) The use of complementary survey J Spinal Cord Med 24: 54–62.

and alternative medicine therapies by patients with advanced cancer and pain in 54. Billhult A, Maatta S, Billhult A, Maatta S (2009) Light pressure massage for

a hospice setting: a multicentered, descriptive study. Journal of Palliative patients with severe anxiety. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 15:

Medicine 12: 7–8. 96–101.

32. Billhult A, Lindholm C, Gunnarsson R, Stener-Victorin E, Gunnarsson R (2009) 55. Diego MA, Field T (2009) Moderate Pressure Massage Elicits a Parasympathetic

The effect of massage on immune function and stress in women with breast Nervous System Response. International Journal of Neuroscience 119: 630–638.

cancer–a randomized controlled trial. Autonomic Neuroscience-Basic & Clinical 56. Stringer J, Swindell R, Dennis M (2008) Massage in patients undergoing

150: 111–115. intensive chemotherapy reduces serum cortisol and prolactin. Psycho-Oncology

33. Back C, Tam H, Lee E, Haraldsson B (2009) The effects of employer-provided 17: 1024–1031.

massage therapy on job satisfaction, workplace stress, and pain and discomfort. 57. Field T, Ironson G, Scafidi F, Nawrocki T, Goncalves A, et al. (1996) Massage

Holistic Nursing Practice 23: 19–31. Therapy Reduces Anxiety and Enhances Eeg Pattern of Alertness and Math

34. Bauer BA, Cutshall SM, Wentworth LJ, Engen D, Messner PK, et al. (2010) Computations. International Journal of Neuroscience 86: 197–205.

Effect of massage therapy on pain, anxiety, and tension after cardiac surgery: a 58. Diego M, Field T, Sanders C, Hernandez-Reif M (2004) Massage therapy of

randomized study. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 16: 70–75. moderate and light pressure and vibrator effects on EEG and heart rate.

35. Sherman KJ, Ludman EJ, Cook AJ, Hawkes RJ, Roy-Byrne PP, et al. (2010) International Journal of Neuroscience 114: 31.

Effectiveness of therapeutic massage for generalized anxiety disorder: a 59. Rapaport MH, Schettler P, Bresse C (2010) A Preliminary Study of the Effects of

randomized controlled trial. Depression & Anxiety 27: 441–450. a Single Session of Swedish Massage on Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal and

36. Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, et al. (1986) Development of Immune Function in Normal Individuals. Journal of Alternative & Comple-

criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis: Classification of mentary Medicine 16: 1–10.

osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the 60. Billhult A, Lindholm C, Gunnarsson R, Stener-Victorin E, Gunnarsson R (2008)

American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 29: 1039–1049. The effect of massage on cellular immunity, endocrine and psychological factors

37. Bellamy N (2005) The WOMAC knee and hip osteoarthritis indices: in women with breast cancer – a randomized controlled clinical trial. Autonomic

Development, validation, globalization and influence on the development of Neuroscience-Basic & Clinical 140: 88–95.

the AUSCAN hand osteoarthritis indices. Clin Exp Rheumatol 23: S148–153. 61. Field T, Diego M, Hernandez-Reif M (2010) Moderate Pressure is Essential for

38. Bellamy N, Buchanan W, Goldsmith C, Campbell J, Stitt L (1988) Validation Massage Therapy Effects. International Journal of Neuroscience 120: 381–385.

study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important 62. Smith M, Kutner J, Hemphill L, Yamashita T, Felton S (2007) Developing

patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with treatment and control conditions in a clinical trial of massage therapy for

osteoarthritis of the hip or knee J Rheumatology 15: 1833–1840. advanced cancer. Journal Of The Society For Integrative Oncology 5: 139–146.

39. Anagnostis C, Mayer TG, Gatchel RJ, Proctor TJ (2003) The million visual 63. Poole A, Ionescu M, Fitzcharles M, Billinghurst R (2004) The assesment of

analog scale: its utility for predicting tertiary rehabilitation outcomes. Spine 28: cartilage degradation in vivo: development of and immunoassay for the

1051–1060. measurement in body fluids of type II collagen cleaved by collagenases.

40. Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Diego M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C (2005) Cortisol J Immunol Methods 294: 145–153.

decreases and serotonin and dopamine increase following massage therapy. 64. Schaible H-G, Grubb B (1993) Afferent and spinal mechanisms of joint pain.

International Journal of Neuroscience 115: 1397–1413. Pain 55: 5–54.

41. Perlman A, Sabina A, Williams AL, Yanchou Njike V, Katz D (2006) Massage 65. Ahles TA, Tope DM, Pinkson B, Walch S, Hann D, et al. (1999) Massage

Therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee. Arch Intern Med 166: 2533–2538. therapy for patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation.

42. Schnyer RN, Allen JJ (2002) Bridging the gap in complementary and alternative Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 18: 157.

medicine research: manualization as a means of promoting standardization and 66. Diego M, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Shaw K, Friedman L, et al. (2001) HIV

flexibility of treatment in clinical trials of acupuncture. Journal of Alternative & adolescents show improved immune function following massage therapy.

Complementary Medicine 8: 623–634. International Journal of Neuroscience 106: 35.

43. Ernst E (2003) The safety of massage therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 42: 67. Sagar SM, Dryden T, Myers C (2007) Research on therapeutic massage for

1101–1106. cancer patients: potential biologic mechanisms. Journal Of The Society For

44. McConnell S, Kolopack P, Davis A (2001) The Western Ontario and McMaster Integrative Oncology 5: 155–162.

Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC): a review of its utility and 68. Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Kahn J, Erro J, Hrbek A, et al. (2005) A survey of

measurement properties. Arthritis Rheum 45: 453–461. training and practice patterns of massage therapists in two US states. BMC

45. Price DD, Bush FM, Long S, Harkins SW (1994) A comparison of pain Complement Altern Med 5: 13.

measurement characteristics of mechanical visual analogue and simple 69. Bronfort G, Haas M, Evans R, Leininger B, Triano J (2010) Effectiveness of

numerical rating scales. Pain 56: 217–226. manual therapies: the UK evidence report. Chiropr Osteopat 18: 3.

PLoS ONE | www.plosone.org 9 February 2012 | Volume 7 | Issue 2 | e30248

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- IM - Patient Esguera (Final)Document4 pagesIM - Patient Esguera (Final)k.n.e.d.No ratings yet

- English For Nursing 2: Vocational English Teacher's BookDocument17 pagesEnglish For Nursing 2: Vocational English Teacher's BookSelina Nguyễn VuNo ratings yet

- The Occasional Intubator: by DR Minh Le Cong RFDS Cairns, April 2011Document55 pagesThe Occasional Intubator: by DR Minh Le Cong RFDS Cairns, April 2011carlodapNo ratings yet

- Bruni-2004-Sleep Disturbances in As A Questionnaire StudyDocument8 pagesBruni-2004-Sleep Disturbances in As A Questionnaire Studybappi11No ratings yet

- 01.classification and Causes of Animal DiseasesDocument16 pages01.classification and Causes of Animal DiseasesDickson MahanamaNo ratings yet

- Roleplay Persalinan Inggris Bu ShintaDocument4 pagesRoleplay Persalinan Inggris Bu ShintaDyta Noorfaiqoh MardlatillahNo ratings yet

- Managment of Sepsis and Septic ShockDocument2 pagesManagment of Sepsis and Septic ShockDavid Simon CruzNo ratings yet

- Augmentin DuoDocument2 pagesAugmentin Duojunaid hashmiNo ratings yet

- A Patient 'S Guide To Refractive SurgeryDocument7 pagesA Patient 'S Guide To Refractive SurgeryJon HinesNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Nicotine and Caffeine AddictionDocument10 pagesIntroduction To Nicotine and Caffeine AddictionUltra BlochNo ratings yet

- Pterygium After Surgery JDocument6 pagesPterygium After Surgery JRayhan AlatasNo ratings yet

- 234 240 PDFDocument7 pages234 240 PDFlegivethNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia in Day Care PDFDocument15 pagesAnesthesia in Day Care PDFHKN nairNo ratings yet

- Myocardial Infarction: Classification of ACSDocument7 pagesMyocardial Infarction: Classification of ACSMaria Charis Anne IndananNo ratings yet

- Phocomelia: A Case Study: March 2014Document3 pagesPhocomelia: A Case Study: March 2014Nexi anessaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Nursing ReviewerDocument17 pagesEmergency Nursing ReviewerChannelGNo ratings yet

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) in Primary Care: A Profile of PracticeDocument8 pagesCanadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) in Primary Care: A Profile of Practiceisabel gomezNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Need For School Clinic During An Outbreak of Covid19 Pandemic in NigeriaDocument7 pagesAssessing The Need For School Clinic During An Outbreak of Covid19 Pandemic in NigeriaOlowolafe SamuelNo ratings yet

- Jurnal NeuroDocument6 pagesJurnal NeuroSiti WahyuningsihNo ratings yet

- Alcoholic Liver DiseasesDocument45 pagesAlcoholic Liver DiseasesSunith KanakuntlaNo ratings yet

- Immunopharmacology: Ma. Janetth B. Serrano, M.D., DPBADocument33 pagesImmunopharmacology: Ma. Janetth B. Serrano, M.D., DPBAJendrianiNo ratings yet

- Deficiencies of Water Soluble VitaminsDocument20 pagesDeficiencies of Water Soluble Vitaminsbpt2No ratings yet

- Biomarkers-A General ReviewDocument17 pagesBiomarkers-A General ReviewKevin FossNo ratings yet

- LARYNX and TRACHEADocument98 pagesLARYNX and TRACHEAPrincess Lorenzo MiguelNo ratings yet

- ECR 2022 ProgrammeDocument1,126 pagesECR 2022 ProgrammejbmbritoNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmology ImpDocument12 pagesOphthalmology Imp074 Jeel PatelNo ratings yet

- Role of NeuropsychologistDocument15 pagesRole of NeuropsychologistMahnoor MalikNo ratings yet

- Final Past Papers With Common MCQS: MedicineDocument17 pagesFinal Past Papers With Common MCQS: MedicineKasun PereraNo ratings yet

- Behcet's Disease: Authors: Jagdish R NairDocument7 pagesBehcet's Disease: Authors: Jagdish R NairsalclNo ratings yet

- Ref 4Document13 pagesRef 4Tiago BaraNo ratings yet