Professional Documents

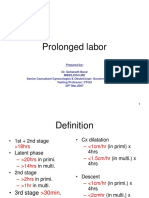

Culture Documents

Anatomia Clitoris Pars Intermedia

Uploaded by

Renzo Cruz CaldasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anatomia Clitoris Pars Intermedia

Uploaded by

Renzo Cruz CaldasCopyright:

Available Formats

1526

ORIGINAL RESEARCH—ANATOMY/PHYSIOLOGY

The Pars Intermedia: An Anatomic Basis for a Coordinated

Vascular Response to Female Genital Arousal jsm_2996 1526..1530

Cheryl Shih, MD,* Christopher J. Cold, MD,† and Claire C. Yang, MD*

*Department of Urology, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA; †Department of Pathology,

Marshfield Clinic, Marshfield, WI, USA

DOI: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02996.x

ABSTRACT

Introduction. The pars intermedia is an area of the vulva that has been inconsistently described in the literature.

Aim. We conducted anatomic studies to better describe the tissues and vascular structures of the pars intermedia and

proposed a functional rationale of the pars intermedia in the female sexual response.

Methods. Nine cadaveric vulvectomy specimens were used. Each was serially sectioned and stained with hematoxylin

and eosin and Masson’s trichrome.

Main Outcome Measures. Histologic ultrastructural description of the pars intermedia.

Results. The pars intermedia contains veins traveling longitudinally in the angle of the clitoris, supported by

collagen-rich stromal tissues. These veins drain the different vascular compartments of the vulva, including the

clitoris, the bulbs, and labia minora; also, the interconnecting veins link the different vascular compartments. The

pars intermedia is not composed of erectile tissue, distinguishing it from the erectile tissues of the corpora cavernosa

of the clitoris as well as the corpus spongiosum of the clitoral (vestibular) bulbs.

Conclusions. The venous communications of the pars intermedia, linking the erectile tissues with the other vascular

compartments of the vulva, appear to provide the anatomic basis for a coordinated vascular response during female

sexual arousal. Shih C, Cold CJ, and Yang CC. The pars intermedia: An anatomic basis for a coordinated

vascular response to female genital arousal. J Sex Med 2013;10:1526–1530.

Key Words. Female Genital Anatomy; Vulva; Pars Intermedia; Clitoris; Corpus Cavernosum

Introduction and connects the clitoral bulbs and corpora caver-

nosa [2]. In either case, it is unclear what role the

I n previous dissections of the female external

genitalia, we encountered the entity known as

the pars intermedia. This is an area immediately

pars intermedia might play in the female sexual

response given its proximity to the sexually

responsive tissues of the vulva. We therefore con-

beneath the midline vulvar skin, between the cli- ducted more detailed studies of the pars interme-

toral body and the commissure of the clitoral (ves- dia so that the anatomical findings could better

tibular) bulbs. Some authors refer to the pars inform our understanding of the role of this struc-

intermedia as the continuation of the erectile ture in the female sexual response.

tissue of the corpus spongiosum in the midline,

above the vestibule of the vagina, joining the bilat-

Materials and Methods

eral clitoral bulbs [1]. Others do not identify the

pars intermedia as erectile tissue but as the venous Nine cadaveric female vulvectomy specimens were

plexus of Kobelt that lies in the angle of the clitoris available for this study. The study was deemed

J Sex Med 2013;10:1526–1530 © 2012 International Society for Sexual Medicine

Pars Intermedia 1527

Figure 1 (A) Gross sagittal section

through the midline urethral meatus (UM)

and vaginal introitus (V). Top of the

picture is anterior, right of the picture is

the perineal surface. The erectile tissue

of the clitoris and clitoral bulbs appear

dark red-brown and spongy. The asterisk

(*) marks the region of the pars interme-

dia. Marker in centimeters. (B) Clay

model (not to scale) of the clitoris

(yellow), clitoral bulbs (red), urethra

(blue), and pars intermedia (green) in the

context of the pelvic bones. The plane

indicates a midline sagittal section.

exempt from institutional review board over- of the clitoral bulbs. The clitoral bulbs are two

sight. The ages of the cadavers were unknown, globular, teardrop-shaped structures connected by

although they appeared to be from postmeno- a commissure and draped over the urethra similar

pausal women. Tissue samples were embalmed in to a saddlebag. The bulbs are composed of the

40% ethanol and 20% glycerin. They were trans- erectile tissue of the corpus spongiosum. Histo-

ferred after sectioning to neutral buffered formalin logically, erectile tissue is characterized by promi-

for processing (formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded nent vascular spaces interspersed by trabeculae of

tissue blocks). smooth muscle and collagen-rich fibrous tissue.

All vulvectomy specimens were serially sec- In addition to erectile tissue, there are nonerec-

tioned and submitted in separate cassette blocks. tile specialized genital vascular tissues, character-

Sections were taken from the clitoral glans and ized by the abundance of vessels interspersed

corpora cavernosa, the anterior vestibule and cli- within fibrous stroma that lacks smooth muscle

toral bulbs, the labia minora, and the labia majora. fibers. These include the tissues of the labia

Serial sections were then stained with hematoxylin minora, periurethra, vestibule/vagina, and glans

and eosin to examine general histologic features. clitoris.

Selected blocks were stained with Masson’s Pars Intermedia

trichrome. In the intervening region between the corpora

cavernosa and the corpora spongiosum of the cli-

Results toral bulbs lies the pars intermedia (Figure 1).

Grossly, the pars intermedia is composed of tissue

Vascular Compartments of the External with large vascular spaces filled with blood. In at

Female Genitalia least one cadaveric specimen, the gross appearance

We have previously described the vascular com- of the pars intermedia was indistinguishable from

partments of the external female genitalia, which the spongy tissue of the corpora cavernosa and

include the erectile tissue of the corpora cavernosa clitoral bulbs. However, in most of the cadavers,

of the clitoris and the clitoral bulbs as well as the the vascular spaces of the pars intermedia appeared

nonerectile specialized genital vascular tissue of larger and more vacuous compared with that of the

the labia minora and vestibule of the vagina [3]. erectile tissues (Figure 2). The area does not have

For the purpose of anatomic orientation and to clear anatomic boundaries.

frame the subsequent description of the pars inter- Histologically, the pars intermedia is very dif-

media, we briefly summarize the vascular compart- ferent from the erectile tissues of the clitoris and

ments here. the clitoral bulbs. Instead of prominent vascular

The clitoris is a wishbone-shaped structure spaces interspersed by thin fibromuscular trabecu-

located beneath the vulvar skin, superficial to the lae as seen in erectile tissue, the pars intermedia is

inferior pubic rami. The clitoral body is composed composed of predominantly collagen-rich stroma

of the erectile tissue of the paired corpora cavern- supporting the veins of Kobelt’s plexus, which cor-

osa. Immediately inferior to the convergence of respond to the large vascular spaces noted on gross

the paired corpora cavernosa lies the commissure examination (Figure 3). Veins from Kobelt’s

J Sex Med 2013;10:1526–1530

1528 Shih et al.

Figure 3 Photomicrograph of the pars intermedia adjacent

to the corpora cavernosa of the clitoris (CC). A thick fibrous

septum (S) separates the corporal bodies. The dense

stroma of the pars intermedia (arrow) contains collagen

(blue), interspersed with smooth muscle bundles (red). The

smooth muscle fibers in the pars intermedia are adjacent to

the vascular spaces and embedded in the stroma, not within

the trabeculae, as they are in erectile tissue. The veins (*) of

Kobelt’s plexus traverse through this stroma and can be

seen to penetrate the tunica albuginea of the corpora cav-

Figure 2 Gross axial section through the fused corpora ernosa. Masson’s trichrome, 20¥.

cavernosa of the clitoral body (CC), the anterior vestibule

(solid arrow), and the pars intermedia (rectangle), which

corresponds to the area depicted by the green clay in the

model in Figure 1. The gross appearance of the erectile

tissues of the corpora cavernosa (CC) is distinct from the

more vacuous tissues of the pars intermedia. The urethra is

not visible on this section because the meatus is deeper in

the perineum. Marker in centimeters.

plexus were observed to penetrate the thick tunica

albuginea of the clitoral corpora cavernosa. These

veins can be seen traveling in the angle of the

clitoris between the glans clitoris and the corporal

bodies, between the erectile tissues of the corpora

cavernosa and the clitoral bulbs, connecting to the

lamina propria of the anterior vestibule (Figure 2),

and into the sexually responsive, nonerectile, spe-

cialized vascular tissues of the labia minora

(Figure 4). Together, the veins of Kobelt’s plexus

and their surrounding stroma make up the pars

intermedia.

Discussion

In this anatomic study of the pars intermedia, we

found that it contains veins traveling longitudi- Figure 4 Photomicrograph of the anterior vestibule. The

nally in the angle of the clitoris, supported by veins of Kobelt’s plexus (*) can be seen in the lamina

propria, connecting the labia minora inferiorly with the other

collagen-rich stromal tissues, and linking the erec- vascular compartments of the female external genitalia. The

tile tissues to the other vascular compartments of vaginal vestibule is lined by nonkeratinized stratified squa-

the female external genitalia. The pars intermedia mous epithelium. Masson’s trichrome, 10¥.

J Sex Med 2013;10:1526–1530

Pars Intermedia 1529

is not composed of erectile tissue, thus distinguish- differential drainage may occur. The veins of the

ing it from the erectile tissues of the corpora cav- pars intermedia appear to be the mechanism by

ernosa of the clitoral body as well as the corpus which coordinated drainage occurs. Although the

spongiosum of the clitoral bulbs. findings of this study are not new, we are now able

In the 1800s, Kobelt provided the first detailed to bring forth a coordinated view of the anatomy

account of the pars intermedia [4]. Kobelt’s plexus of the female genitalia, in the context of genital

of veins make up the pars intermedia, “which on physiology.

both sides lies under the corpus clitoridis and is in The pars intermedia is a collection of veins sup-

direct contact with the upper end of the bulbus ported by dense stroma, which is different from

vestibule” [4]. He goes on to describe venous the erectile tissues of the clitoris and clitoral bulbs.

tributaries from the clitoris, the corpus spongio- It is a continuation of the clitoral bulbs only in the

sum, the frenulum, and the labia minora that feed sense that the veins penetrate the corpus spongio-

into the plexus. “[The veins] are to be equated with sum and link it to the other vascular compartments

the venae communicantes between the corpus of the female external genitalia. These veins, by

spongiosum urethrae and the corpus spongiosum means of their number and size, appear to be the

penis” in the male [4]. primary venous drainage of the sexually responsive

Recent studies have also described the pars tissues of the vulva. The dorsal veins of the clitoris,

intermedia but not to the degree of detail as we which also provide venous drainage of the corpora

have in our investigation. Foldes and Buisson [5,6] cavernosa, appear to be a secondary venous system

were able to visualize the pars intermedia on sono- and restricted to the clitoris.

graphic images as a distinct part of the clitoral Although the different parts of the vulva have

complex. O’Connell et al. [7,8] referred to “a been described for centuries, we have only recently

double row of veins surrounding the distal urethra begun to consider these parts as a whole and to

adjacent to the bulbs” and implied that the pres- study how they respond in a coordinated fashion

ence of the pars intermedia is controversial and the during sexual arousal. Here, we present the

anatomical region is not readily identifiable; while anatomy of the pars intermedia and speculate on

van Turnhout et al. [1] used both surgical and its role in the coordinated vascular response of the

cadaveric specimens to conclude that the pars external female genitalia. This has implications for

intermedia is a part of the corpus spongiosum and surgical procedures that could potentially disrupt

a continuation of the bilateral clitoral bulbs. the vascular communications of the pars interme-

However, there is a clear distinction between the dia, such as transvaginal incontinence procedures,

pars intermedia and the corpus spongiosum. While radical urethrectomy, vulvectomy and other

on gross examination in fixed cadaveric tissue, the exenterative procedures for malignancy, and

pars intermedia appears spongy and bloodstained plastic reconstructive procedures of the perineum.

similar to the neighboring corpus spongiosum of This also has implications for our understanding

the clitoral bulbs; on histologic examination, it is of female sexual dysfunction, which affects

clear that these tissues are distinct. approximately 40% of American women [10].

These vascular channels of the pars intermedia, Despite its high prevalence, relatively little is

as Kobelt depicted in his illustration [2], were known about its physiology and pathophysiology.

observed to penetrate the erectile tissues and A more complete understanding of female vulvar

receive tributaries from the various vascular com- anatomy and vascular physiology, including the

partments of the female external genitalia. Clinical role of the pars intermedia, will be helpful in the

and magnetic resonance imaging studies have development of medical therapies for female

shown that the clitoris, clitoral bulbs, and labia sexual dysfunction as well as surgical modifications

minora simultaneously engorge during arousal for female genital surgery.

[3,9]. The confluence of the veins between the Limitations of this study include the lack of

vascular compartments within the pars intermedia demographic and clinical information on our

leads us to speculate that this arrangement pro- cadaveric specimens, restricting our ability to draw

vides the anatomic basis for a coordinated vascular clinical conclusions from our neuroanatomical

response during female sexual arousal. In order to findings. This is a common limitation of cadaveric

accommodate the higher rates of blood flow studies. Surgical pathology vulvectomy specimens

during arousal and maintain simultaneous have associated clinical data but are usually altered

engorgement between the vascular tissues, the vas- by malignancy and, therefore, also difficult to

cular drainage needs to be interconnected, or else interpret.

J Sex Med 2013;10:1526–1530

1530 Shih et al.

Conclusion (c) Analysis and Interpretation of Data

Claire C. Yang; Christopher J. Cold; Cheryl Shih

The pars intermedia is composed of the veins of

Kobelt’s plexus, supported by dense fibromuscular

stroma, running in the region under the angle of Category 2

the clitoris, and linking the erectile tissues of the (a) Drafting the Article

corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum to the Claire C. Yang; Cheryl Shih

other vascular compartments of the female exter- (b) Revising It for Intellectual Content

nal genitalia. The venous communication of these Claire C. Yang; Christopher J. Cold; Cheryl Shih

vascular compartments provides the anatomic

basis for a coordinated vascular response during

female sexual arousal. Category 3

(a) Final Approval of the Completed Article

Claire C. Yang; Christopher J. Cold; Cheryl Shih

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Dr. John Harting, Dr. Ed

Schultz, and the University of Wisconsin, Madison References

School of Medicine and Public Health for assistance 1 van Turnhout AA, Hage JJ, van Diest PJ. The female corpus

with cadaver dissections, the Marshfield Histology spongiosum revisited. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1995;74:

Laboratory for assistance with histology and special 767–71.

stains, and Dr. Van Ginger of the Polyclinic, Seattle, 2 Dickinson RL. Human sex anatomy: A topographical hand

WA, for her pilot work on this project. The authors atlas. 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins

would also like to thank Marie Fleisner of the Marsh- Company; 1949.

3 Yang CC, Cold CJ, Yilmaz U, Maravilla KR. Sexually respon-

field Clinic Research Foundation, Marshfield, WI, for

sive vascular tissue of the vulva. BJU Int 2006;97:766–72.

editorial assistance. 4 Kobelt GL. The female sex organs in humans and some

mammals. In: Lowry TP, ed. The classic clitoris: Historic

Corresponding Author: Cheryl Shih, MD, Depart- contributions to scientific sexuality. Chicago, IL: Nelson-Hall;

ment of Urology, University of Washington School of 1978:19–56.

Medicine, 1959 NE Pacific St, Box 356510, Seattle, WA 5 Foldes P, Buisson O. The clitoral complex: A dynamic sono-

98195, USA. Tel: 206-543-3640; Fax: 206-543-3272; graphic study. J Sex Med 2009;6:1223–31.

E-mail: csshih@uw.edu 6 Buisson O, Foldes P, Jannini E, Mimoun S. Coitus as revealed

by ultrasound in one volunteer couple. J Sex Med 2010;7:

Conflict of Interest: None to report. 2750–4.

7 O’Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM. Anatomy of the

clitoris. J Urol 2005;174:1189–95.

Statement of Authorship 8 O’Connell HE, Eizenberg N, Rahman M, Cleeve J. The

anatomy of the distal vagina: Towards unity. J Sex Med 2008;5:

Category 1 1883–91.

9 Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual response. 1st

(a) Conception and Design edition. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1966.

Claire C. Yang; Christopher J. Cold; Cheryl Shih 10 Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the

(b) Acquisition of Data United States: Prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281:

Christopher J. Cold; Cheryl Shih 537–44.

J Sex Med 2013;10:1526–1530

You might also like

- Tecnicas de Morcelacion UterinaDocument11 pagesTecnicas de Morcelacion UterinaRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Corticoides para Maduracion Pulmonar ACOG 2017Document8 pagesCorticoides para Maduracion Pulmonar ACOG 2017Renzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Cambiando Ruta de Histerectomia Acog 2017Document5 pagesCambiando Ruta de Histerectomia Acog 2017Renzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Manejo Del Liquido Meconial Al Inicio de Labor de Parto Acog 2017Document2 pagesManejo Del Liquido Meconial Al Inicio de Labor de Parto Acog 2017Renzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Hidradenitis SuppurativaDocument52 pagesHidradenitis SuppurativaRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Frecuencia Cardiaca Fetal en Vasa Previa e Insercion Velamentosa de CordonDocument7 pagesFrecuencia Cardiaca Fetal en Vasa Previa e Insercion Velamentosa de CordonRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- PAM Con Punto de Corte 90 Tiene Una SensibilidadDocument8 pagesPAM Con Punto de Corte 90 Tiene Una SensibilidadRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- 01-Lambert Et AlDocument13 pages01-Lambert Et AlPrastia StratosNo ratings yet

- Sulfato de Magnesio No Previene El Parto Pretermino Como Tocolitico 2014Document89 pagesSulfato de Magnesio No Previene El Parto Pretermino Como Tocolitico 2014Renzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Terapia de Cambio Plasmatico para HELLP PDFDocument5 pagesTerapia de Cambio Plasmatico para HELLP PDFRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Antibioticos para Procedimientos 2013Document8 pagesAntibioticos para Procedimientos 2013Renzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Imagenes de HisterectomiaDocument8 pagesImagenes de HisterectomiaRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Hypoglycemia in PregnancyDocument6 pagesHypoglycemia in PregnancyRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- 2013 Sepsis GuidelinesDocument58 pages2013 Sepsis GuidelinesMuhd Azam100% (1)

- 2543 FullDocument23 pages2543 FullRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- Guideline For Emergency Oxygen Use in Adult PatientsDocument81 pagesGuideline For Emergency Oxygen Use in Adult PatientsMuhammad RusydiNo ratings yet

- Tiroide GuidlinesDocument47 pagesTiroide GuidlinesRenzo Cruz CaldasNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Sesión 16. The Value of Canine Semen Evaluation For PractitionersDocument9 pagesSesión 16. The Value of Canine Semen Evaluation For PractitionersPavel Hunter RamírezNo ratings yet

- Lecture-15 Prolonged LaborDocument8 pagesLecture-15 Prolonged LaborMadhu Sudhan PandeyaNo ratings yet

- 2.03B Fetal Assessment Part 2 (Dr. Candelario) PDFDocument7 pages2.03B Fetal Assessment Part 2 (Dr. Candelario) PDFjay lorenz joaquinNo ratings yet

- Cleaning Your PenisDocument11 pagesCleaning Your PenissearchhistorycollectionNo ratings yet

- Bleeding in Second Half (Late) of PregnancyDocument21 pagesBleeding in Second Half (Late) of PregnancyIdiAmadouNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 Science ReviewerDocument25 pagesGrade 10 Science ReviewertinaNo ratings yet

- Gland Location Hormone Chemical Nature Target Structure Function Hypersecretion HyposecretionDocument6 pagesGland Location Hormone Chemical Nature Target Structure Function Hypersecretion Hyposecretiondave_1128No ratings yet

- Teenage Pregnancy - pptx2Document48 pagesTeenage Pregnancy - pptx2Glenn L. Ravanilla100% (4)

- Preecha's Technique MtF. (The Pioneer in Sex Reassignment Surgery, Thailand) - 1Document7 pagesPreecha's Technique MtF. (The Pioneer in Sex Reassignment Surgery, Thailand) - 1VeroniqueNo ratings yet

- Maternity Nursing An Introductory Text 11th Edition Leifer Test BankDocument9 pagesMaternity Nursing An Introductory Text 11th Edition Leifer Test BankSerenaNo ratings yet

- Julie A Greenberg - Intersexuality and The Law Why Sex MattersDocument180 pagesJulie A Greenberg - Intersexuality and The Law Why Sex MattersLaura Belli100% (1)

- Marking Scheme: Worksheet 5.2: Questions On Cell DivisionDocument2 pagesMarking Scheme: Worksheet 5.2: Questions On Cell DivisionBGNo ratings yet

- Get A Girl You LikeDocument9 pagesGet A Girl You LikeKollin2150% (2)

- Fetal Heart Rate Interpretation Adaptation To LaborDocument36 pagesFetal Heart Rate Interpretation Adaptation To Laboryolondanic100% (1)

- 20.operational Work Plan Template PDFDocument2 pages20.operational Work Plan Template PDFPeter GathagaNo ratings yet

- CH 8 How Do Organisms ReproduceDocument17 pagesCH 8 How Do Organisms ReproduceShlok GhanwatNo ratings yet

- UTS-The Sexual SelfDocument31 pagesUTS-The Sexual SelfJake Casiño90% (10)

- Oral Contraceptive MCQs With Answer KeyDocument7 pagesOral Contraceptive MCQs With Answer KeyShaista AkbarNo ratings yet

- Biology - The Genetics of Parenthood AnalysisDocument2 pagesBiology - The Genetics of Parenthood Analysislanichung100% (5)

- ManuscriptDocument6 pagesManuscriptYahyaNo ratings yet

- IcdDocument21 pagesIcdVicky AprizanoNo ratings yet

- HOTS SOLO QUESTIONS - FORMAT Melc 34 V1 EditedDocument3 pagesHOTS SOLO QUESTIONS - FORMAT Melc 34 V1 Editedjinky luaniaNo ratings yet

- Scientific Paper Ratna Scientific PaperDocument9 pagesScientific Paper Ratna Scientific PapermahalNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Study On Effect of Ambulation and Birthing Ball On Maternal and Newborn Outcome Among Primigravida Mothers in Selected Hospitals in MangalorDocument4 pagesA Comparative Study On Effect of Ambulation and Birthing Ball On Maternal and Newborn Outcome Among Primigravida Mothers in Selected Hospitals in MangalorHella WarnierNo ratings yet

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease (GTD) Part I: Molar PregnancyDocument88 pagesGestational Trophoblastic Disease (GTD) Part I: Molar Pregnancyhafidzz1100% (1)

- Kriteria Diagnosis ObgynDocument6 pagesKriteria Diagnosis ObgynJustisiani Fatiria, M.D.No ratings yet

- Unit 3. PlantsDocument10 pagesUnit 3. PlantsMartabm29No ratings yet

- Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationDocument20 pagesCambridge International General Certificate of Secondary EducationSuhaan HussainNo ratings yet

- Who Preterm Birth 2018Document5 pagesWho Preterm Birth 2018Santi Ayu LestariNo ratings yet

- Arthropods of Medical ImportanceDocument6 pagesArthropods of Medical ImportanceMiren Sofia Jordana0% (1)