Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Larson 1978 PDF

Larson 1978 PDF

Uploaded by

2704honeyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Larson 1978 PDF

Larson 1978 PDF

Uploaded by

2704honeyCopyright:

Available Formats

NANCY LARSON-POWERS’ and ROSE MARIE PANGBORN

Food Science & Technology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS O F THE SENSORY PROPERTIES O F

BEVERAGES AND GELATINS CONTAINING SUCROSE O R SYNTHETIC SWEETENERS’

ABSTRACT the samples, with recommendations for substanceswhich could serve as

physical references in subsequent sessions. All impressions were dis-

Two descriptive sensory methods, anchored (deviation from a sucrose cussed by the group, definitions established, and references agreed

reference) and unanchored, were used to quantify differences in aroma, upon. The panel leader developed preliminary score cards and brought

flavor and aftertaste in five media - strawberry, lemon and orange reference materials to anchor aroma terminology at the following

drinks, and strawberry and orange gelatins - varying in type of training sessions. ,After agreement was reached on appropriate

sweetener. With both methods, samples sweetened with sodium saccha- descriptors and references (six to eight sessions),the score sheetswere

rin deviated the most from the sucrose standard, those sweetened with finalized for each stimuli - strawberry, orange and lemon drinks, and

aspartame the least, and calcium cyclamate was intermediate. In

strawberry and orange gelatins. At all test sessionsthereafter, judges

general, drinks sweetened with sucrose or with aspartame could be

characterized as “sweet-clean,” and those sweetened with cyclamate or evaluated samples individually at a partitioned round table with no

group discussion. The aroma references were continually available from

with saccharin as “sweet-chemical” and “bitter.” Gelatins containing a rotating “lazy Susan.”

synthetic sweeteners generally were more astringent, bitter and sour,

with less strawberry flavor, and were significantly less hard, springy and Samples were served at 3°C in 80-ml blue cobalt glassesimmersed in

viscous than those sweetened with sucrose. In all media, more signifi- ice water. The glasseswere covered with aluminum lids containing two-

cant differences were observed among the sweetenerswith the anchored or three-digit codes, and were served as a complete block in randomized

method than with the unanchored procedure. Advantages and limita- order. At each session, four samples were presented, one from each

tions of these two quantitative descriptive procedures are discussed. sweetener - sucrose, aspartame, sodium saccharin, or calcium cycla-

mate. The concentrations of each sweetener are given in Figures l-10.

For beverages, IO-ml samples were served for aroma evaluation, and

60-ml samples for evaluation of flavor and aftertaste. For gelatin, six

INTRODUCTION 2-cm cubes were served. For each of the five stimuli (three drinks and

two gelatins), five sessionswere held. This relatively small number of

PAIRED COMPARISON and time-intensity methods were replicate sessions,which totalled 4 wk of daily testing/commodity, was

used to measure the relative taste intensities of flavored drinks necessitated by the availability of the student judges during various

and of gelatins sweetened with sucrose, aspartame, sodium academic sessions.Within each stimulus, the fist sessionwas considered

saccharin, or calcium cyclamate (Larson-Powers and Pangborn, orientation, and the data were not included in the final tally. At the

1978). In addition to these quantitative measures, qualitative next three sessions,samples were evaluated in terms of deviation from a

attributes of the aromas, tastes and aftertastes of these stimuli sucrose reference, i.e., using an anchored, descriptive analysis. At the

were established by two descriptive procedures: multiple-com- fifth and final session, unanchored descriptive analysis was used, i.e.,

parison, unanchored, and anchored to a sucrose reference the four samples were presented simultaneously and judged on an abso-

lute basis, on an unstructured scale consisting of a loo-mm horizontal

(Larson, 1975). Preliminary testing of commercial milk line labeled “none” to “extreme” for each descriptor.

chocolate, using the anchored descriptive analysis, gave greater The anchored, descriptive analysis was a modification of a method

reproducibility of response than did unanchored methods, reported by Daget (1974) for evaluating chocolate. The sensory data

such as the nonquantitative A.D. Little “Flavor Profile” (Caul, obtained was analyzed by Vuataz et al. (1974). In the present study,

1957) and the General Foods “Textural Profile” (Civille and judges indicated the degree of difference in intensity of each character-

Szczesniak, 1973) or Tragon’s “Quantitative Descriptive istic from the reference (the sucrose-sweetenedsample) by placing a

Analysis” (Stone et al., 1974). The present paper evaluates the mark on an unstructured, horizontal line, 120 mm in Iength, IabeIed

data from the anchored and unanchored descriptive techniques “Less” and “More” at the ends, with the center labeled “Same as

Reference.” A hidden reference, the sucrose-sweetenedsample, was

and contrasts them with information derived from the included as a coded, test sample to check the internal variation of the

previous quantitative methods. judges’responses.

A fixed model analysis of variance was applied to the individual

MATERIALS & METHODS scores within each of the five stimuli, for aroma, for flavor and for

THE SWEETENERS, the powdered bases for the drinks and gelatins, aftertaste descriptors separately. Main effects tested were sweeteners,

and the procedures for their preparation have been described previously descriptors, judges, and replications, as well as all two- and three-way

(Larson-Powersand Pangborn, 1978). interactions. Least significant differences were calculated for all signifi-

cant sweetener x descriptor interactions.

Sensory procedures

Five females and one male served as judges for the drinks, and four RESULTS & DISCUSSION

females and two males for the gelatins. Two additional females parti-

cipated in the development of vocabulary and in sessions using un- Drinks

anchored description of all products. However, because these two sub- Because of the great similarity in the responses to the

jects prepared and served samples and hence knew of the “blind” strawberry, lemon and orange drinks, only results from the

sample, their responses were not recorded in the data obtained from

anchored descriptive analysis. Judges were students or employees, be- orange drink will be presented herein. The complete set of

tween the ages of 22-35 yr, selected on the basis of interest in partici- data are available in the thesis by the senior author (Larson,

pation in extended groups sessions,and ability to reproducibly describe 1975).

flavor attributes of the test samples. These judges developed a vocabu- Anchored descriptive analysis. Responses to the aroma, fla-

lary of terms to describe the aroma, flavor and aftertaste of the sam- vor and aftertaste of the sucrose sample compared with itself

ples in daily group sessions of approximately 1-hr’s duration. At the as a blind control are shown in Figure 1. The mean deviation

onset of each group meeting, judges listed all terms which applied to did not exceed +-5 mm on the 120-mm intensity scale, at-

testing to the ability of the group to match the reference to

itself. The magnitude of the standard deviations indicate good

I Present address: 1015 Campbell,Prosser.WA 99350 agreement on aftertaste, with greater variation for aroma and

Volume 43 /1978)-JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE- 47

P O.O7%ASPARTAME IN ORANGE DRINK

5 10% SUCROSEINORANGE DRINK

AROMA -FLAVOR- +AFTERTASTE----I

AROMA -FLAVOR- k-AFTERTASTE+

Fig. lAMean intensity differences and standard deviations for the Fig. P-Mean intensity differences and standard deviations for the

sensory characteristics of orange drink with 10% sucrose, compared sensory characteristics of orange drink with 0.07% aspartame com-

with itself as a reference. pared with the 10% sucrose reference.

selected flavor terms. The large standard deviations for general istics among, rather than within judges, as the F ratios for

descriptors like “Overall Aroma” and “Overall Flavor” indi- replication were not significant in the analysis of variance (df =

cate lack of concurrence among the judges, possibly because it 2/390, F = 2.10 for aroma, 1.81 for flavor, and 2.50 for after-

was impossible to provide a reference sample for those taste). Furthermore, the interactions of sweetener by replica-

descriptors. The best match and greatest group agreement was tion, and of sweetener by descriptor were not significant.

for bitter flavor and bitter aftertaste. Large variations among judges also were reported by Daget

Figures 2, 3 and 4 depict the direction and magnitude of (1974) who used a similar method to characterize the sensory

difference of the sensory characteristics of orange drink properties of milk chocolate.

sweetened with aspartame, cyclamate or saccharin, contrasted

with the sucrose-sweetened reference. Samples sweetened with Unanchored descriptive analysis. Results from the un-

saccharin deviated the most and those sweetened with anchored descriptive analysis method permits intercomparison

aspartame deviated the least from the reference. “Overall fla- among all four sweeteners in orange drink (Fig. 5a and Sb). No

vor,” the composite of all oral sensations, was significantly significant differences in overall aroma were obtained. Only

greater in the cyclamate and saccharin samples (Fig. 3 and 4). two of the 13 individual arom,a descriptors differed signifi-

The term “sweet chemical,” used to describe a synthetic-type cantly among the sweeteners - “fresh orange peel,” and

of sweetness (in contrast with “sweet clean,” which was associ- “orange-flavored aspirin,” which were more intense in the su-

ated with the sucrose sample), was significantly more pro- crose sample. For flavor, overall intensities did not differ sig-

nounced in the cyclamate samples, both in flavor and in after- nificantly but seven of the 16 individual flavor descriptors did

taste. For the saccharin sample, however, “astringent” and (Fig. Sa). In general, drinks sweetened with sucrose or with

I

“bitter” flavors were significantly more intense than for the aspartame could be characterized as “sweet-chemical,” and

sucrose reference. Large standard deviations were obtained, “bitter.” Sucrose and saccharin imparted more astringency

particularly for the drink containing saccharin (Fig. 3). This is than did the other two sweeteners. Saccharin was considered

attributed to the variation in perceived intensity of character- significantly more sour than the other sweeteners, possibly due

O.l%SACCHARIN IN ORANGE DRINK

0.65% CYCLAMATE IN ORANGE DRINK

T

AROMA -FLAVOR- +AFTERTASTE -4 AROMA -FLAVOR- +AFTERTASTE+

Fig. d-Mean intensity differences and standard deviations for the Fig. 4-Mean intensity differences and standard deviations for the

sensory characteristics of orange drink with 0.65% cyclamate com- sensory characteristics of orange drink with 0.1% saccharin com-

pared with the 10% sucrose reference. pared with the IO!% sucrose reference.

48 -JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE-Volume 43 (19781

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF BEVERAGE/GELATIN SENSORY PROPS. . .

ORANGE DRINK

I Sucrose IO%

q Asportome 0.07%

Socchorin 0.1%

Over0I I Fresh Oronge Overall Astringent Sweet Sweet Bitter Sour Oronge Corbonoted

Aroma Orange Flovored Flovor Clean Chemical Popsicle OmngeDrink

Peel Aspirin

-AAOMA- I FLAVOR I

Fig. 5a-Mean intensities for aroma and flavor characteristics of orange drink for each of four sweeteners. (Unanchored de-

scrip tive analysis)

to the judges’ association of sourness with bitterness, as ob- ORANGE DRINK

served also by other investigators (Meiselman and Dzendolet,

1967; Robinson, 1970). The comparative means and standard I Sucrose 10%

deviations (SD) for sourness and bitterness, respectively, were q Asportome 0.07%

0 Cyclomote 0.65%

12.8 + 14.4 and 4.9 f 11.8 for sucrose samples, and 37.5 + I Saccharin 0.10 %

29.1 and 37.4 + 39.3 for the saccharin samples. For the su- rl

crose series, the foregoing SD fall within the same range as the

SD for other descriptors. For the saccharin series, however,

these SD are much higher than the SD for most other

descriptors. In retrospect, we might have grouped the terms

into a composite called “sour-bitter.” Of the 11 terms used to

describe aftertaste, seven differed in intensity among the four

sweeteners (Fig. 5b). Again, samples with sucrose or aspartame Astringent Sweet Sweet Sticky Bitter Oronge Medicinal

Clean Chemical Sweet Flavored

were “sweet-clean,” and those with cyclamate or saccharin Aspirin

were “sweet chemical.” The saccharin sample continued to

exhibit an astringent and bitter aftertaste, while the cyclamate

sample had a cloying, “sticky-sweet” aftertaste. These latter

Fig. 5b-Mean intensities for the aftertastes of orange drink for each

sweeteners were considered medicinal, also.

of four sweeteners. Wnanchored descriptive analysis)

Intercomparison of the means and of the analyses of vari-

ance for the two descriptive methods, showed that for all

drinks, the anchored method (comparison with the sucrose

reference) was more sensitive. More significant differences

were observed among the sweeteners for more descriptors by

the anchored, than by the unanchored procedure. Part of these 18% SUCROSEIN STRAWBERRYGELATIN

differences may be attributable to the smaller number of judg-

ments collected by the unanchored procedure, and by the se-

quence of presentation of methods, i.e., the three “anchored”

sessions always preceded the “unanchored” session.

Gelatins

Similar results were obtained for the two gelatins - orange

and strawberry; therefore, only the data from the latter are

presented herein.

Anchored descriptive analysis. In gelatin, aroma could not

be broken down into individual characteristics. Consequently,

only “overall aroma intensity” was examined. Comparison of

the sucrose sample against itself showed that only one term,

“sour” deviated from the reference by more than 5 m m on the AROMA -FLAVOR- -AFTERTASTE-

120-mm scale (Fig. 6), demonstrating good internal con-

sistency of the judges as a group. Small standard deviations

were obtained for terms such as “bitter” and “metallic” but an Fig. 6-Mean intensity differences and standard deviations for the

exceptionally large standard deviation was obtained for the Sensory characteristics of strawberry gelatin with 18% sucrose, com-

key flavor term, “strawberry.” it is suspected that judges used pared with itself as a reference.

Volume 43 (19781--JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE- 49

0.105% ASPARTAMEINSTRAWBERRYGELATIN different criteria for evaluating the complex sensations they

labeled as “strawberry.”

The direction and magnitude of difference from the su-

crose reference of strawberry gelatin sweetened with synthetic

sweeteners are depicted in Figures 7, 8 and 9. In most charac-

teristics, aspartame differed the least, and saccharin differed

the most from the reference. Gelatins containing synthetic

sweeteners were significantly less hard, springy and viscous

than the sucrose reference. This is consistent with results ob-

tained in time-intensity studies, where gelatin sweetened with

sucrose was firmer than gelatin containing the synthetic

sweeteners (Larson-Powers and Pangborn, 1978). As noted in

Figures 7, 8 and 9, much less strawberry flavor and strawberry

aftertaste was reported for synthetically-sweetened gelatins (P

< 0.05). Gelatins with cyclamate and with saccharin had sig-

nificantly more bitter flavor and bitter aftertaste than did the

samples with sucrose. Considerable sourness was ascribed to

the’saccharin sample. Again, it should be mentioned that many

tasters equate, or confuse sensations of sourness and bitter-

Fig. 7-Mean intensity differences and standard deviations for the

ness.

sensory characteristics of strawberry gelatin with 0.105% aspartame Unanchored descriptive analysis. In Figure 10, mean in-

compared with the 18% sucrose reference.

tensity values are presented for gelatins evaluated simul-

taneously in a multiple-sample presentation. Significant dif-

0.55%CYCLAMATE IN STRAWBERRYGELATIN ferences (P < 0.05) were obtained among the four sweeteners

v I

for the descriptors “sweet,” “bitter,” and “strawberry”

flavors. Again, samples with sucrose or with aspartame were

sweeter, less bitter, and had more strawberry flavor than did

samples containing cyclamate or saccharin. Bitter, sour, and

medicinal aftertastes were more perceptible in these latter sam-

ples, also. A greater number of descriptors differed signifi-

cantly among the four sweeteners using the anchored analysis

than by the unanchored method, as indicated previously for

the drinks.

CONCLUSIONS

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSES allowed intercomparison of

multiple sensory characteristics, rather than a single parameter

as described previously for paired-directional tests and time-

intensity testing (Larson-Powers and Pangborn, 1978).

AROMA -FLA”OR- -AFTERTASTE-

Anchoring the description to a reference, and expressing re-

sults in terms of the positive and negative deviation from the

reference improved both the precision and the accuracy of the

Fig. 8-Mean intensity differences and standard deviations for the

responses, compared to the unanchored descriptive method.

sensory characteristics of strawberry gelatin with 0.55% cyclamate

In all five test media - strawberry, lemon and orange

compared with the 18% sucrose reference.

drinks, and strawberry and orange gelatins - the anchored

method resulted in a greater number of descriptors which were

significantly different among the four sweeteners, indicating it

0.05% SACCHARIN IN STRAWBERRYGELATIN

was more sensitive than the unanchored method. Comparison

1 of, analyses of variances between anchored and unanchored

test data showed much higher F ratios for sweeteners for the

former, and higher F ratios for judges for the latter method. In

other words, we found more differences among sweeteners in

the anchored, and more judge variability in the unanchored

method. Again, it should be noted that there were fewer judg-

ments with the latter method.

Additional real and potential advantages of an anchored

descriptive method would include: (a) Provision of an internal

measure of judge reliability by comparison of the reference

against itself as a blind sample; (b) Provision of a fixed

criterion of comparison to minimize drifting of responses with

time, or comparison against faulty memory standards; (c) In

incomplete block designs where samples cannot be compared

against each other, there is a potential increase in reliability

because they can all be compared against the same standard;

(d) In product matching or product formulation, the method

AROMA -FLAVOR- -AFTERTASTE----I

provides a quick measure of attributes, and hence ingredients,

which need to be increased or decreased relative to a fixed

Fig. g-Mean intensity differences and standard deviations for the reference.

sensory characteristics of strawberry gelatin with 0.05% saccharin ‘The disadvantage of the anchored method would include an

comoared with the 18% sucrose reference. indirect, rather than a direct knowledge of the degree to which

!jo -JOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE-Volume 43 (19781

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS OF BEVERAGE/GELATIN SENSORY PROPS.. .

Strawberry Gelatin

I SUCROSE 18%

'43 ASPARTAME 0.105%

0 CYCLAMATE 0.55%

q SACCHARIN 0.05%

Fig. IO-Mean intensities for aroma, flavor and

aftertaste characteristics of strawberry gelatin

for each of four sweeteners. (Unanchored

descriptive analysis)

;VLE[f&L SWEET BITTER STRAWBERRY OVERALL SWEET BITTER SOUR MEDICINAL

oE%.L AFTERTASTE

AROMA -FL AVOR- V-AFTERTASTE- I

samples compare with each other. In studies in which it is Larson, N.L. 1975. Sensory Properties of Flavored Beverages and Gela-

difficult to designate a reference, the anchored method would, tins Containine: Sucrose or Synthetic Sweeteners. M.S. thesis. Uni-

versity of Calif&nia, Davis.

of course, be of limited value. Larson-Powers. N. and Pangborn. R.M. 1978. Paired comparison and

Relative to the sweeteners, samples containing sucrose or time-intensity measurements of the sensory properties of beverages

and gelatins containing sucrose or synthetic sweeteners. J. Food Sci.

aspartame had little bitterness and were termed “sweet clean,” 43: 41.

whereas those containing cyclamate or saccharin were very Meiselman, H.L. and Dzendolet, E. 1967. Variability in gustatory

bitter and were labeled “sweet chemical.” These observations auality identification. Perception & Psychophysics 2(11): 496.

Robinson, J.O. 1970. The misuse of taste names by. untrained ob-

on sweetness and ,bitterness are in agreement with conclusions servers. British J. Psychology 61(3): 375.

obtained using the time-intensity technique (Larson-Powers Stone, H., Sidel, J., Oliver. S., Woolsey. A. and Singleton, R.C. 1974.

Sensory evaluation by quantitative descriptive analysis. Food

and Pangborn, 1978). Technol. 28(11): 24

Vuataz, L., Sotek. J. and Rahim. H.M. 1974. Profile analysis and classi-

fication. Proceedings. 4th International Congress of Food Science &

Technology. lap. 25, Madrid, Spain.

REFERENCES Ms received 512177: revised 814177: accented 8/12/77.

Gaul, J.F. 1957. The profile method of flavor analysis. Adv. Food Res.

7: 1. Based on a thesis submitted by the senior author to the Univ. of

Civille. C.V. and Szczesniak, A.S. 1973. Guidelines to training a textrue California, in partial fulfillment of the MS. degree. 1975.

profile panel. J. Texture Studies 4(2): 204. The research was supported. in part. by Searle Biochemics,

Daget, N. 1974. Profile sensory evaluation of chocolates. Paper Arlington Heights, IL.

presented at “Erster Internationaler Kongress i;ber Kakao und The technical assistance of Mrs. Cathy Tassan is gratefully acknowl-

Schokoladeforschung.” M&hen. edged.

BIOCHEMICAL CHANGES IN SURF CLAM MUSCLE. . .From page 37

Hoff, J.C., Beck, W.J., Ericksen. T.H., Vasconcelos, G.J. and Presnell, Newbold. R.P. 1966. Changes associated with rigor mortis. In “The

M.W. 1967. Time-temperature effects on the bacteriological quality Physiology and Biochemistry of Muscle as a Food,” p. 213. Uni-

of shellfish. J. Food Sci. 32: 121. versity of Wisconsin Press, Madison, WI.

Hohorst. H.J. 1963. L-(+)-lactate. Determination with lactic dehydro- Partmann, W. 1965. In “The Technology of Fish Utilization,” p. 4.

genase and DPN. In “Methods of Enzymatic Analysis,” p. 266. Fishing News (Books) Inc., London.

Academic Press, New York. Porter, R.W. 1968. The acid-soluble nucleotides in king crab muscle. J.

Lee. Y.B.. Kauffman. R.G., Grummer. R.H., Schmidt, G.R. and Food Sci. 33: 311.

Briskey, E.J. 1971. Effect of fasting and refeeding on some chemical Sidhu, G.S., Montgomery, W.A. and Brown, M.A. 1974. Postmortem

properties of porcine muscle. J. Animal Sci. 32: 457. changes and spoilage in rock lobster muscle. 1. Biochemical changes

Lee, Y.B., Hargus, G.L., Hagberg. E.C. and Forsythe, R.H. 1976. Effect and rigor mortis in Jaws novaehollandiae. J. Food Tech. 9: 357.

of antemortem environmental temperatures on postmortem glycoly- Tarr. H.L.A. 1966. Postmortem changes in glycogen. nucleotides. sugar

sis and tenderness in excised broiler breast muscle. J. Food Sci. 41: phosphates, and sugars in fish muscles. J. Food Sci. 31: 846.

1466. MS received 3116177: revised 5/21/77: accepted 5125177.

Lemprecht, W. and Trautschold, I. 1963. Adenosine-5-triphosphate.

Determination with hexokinase and glucose-6-Dhosuhate dehydro-

genase. In “Methods of Enzymatic knalysis,‘i p. 543. Academic

Press, New York.

Marsh, B.B. 1952. Observations on rigor mortis in whale muscle. Bio- Presented at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Institute of Food

chii. Biophys. Acta 9: 127. Technologists. Philadelphia, PA, June 5-8.1977.

Volume 43 (1978kJOURNAL OF FOOD SCIENCE- 51

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5810)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (347)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Black GooDocument10 pagesBlack GooAlloya Huckfield100% (1)

- Naming: Aphasia Screening TestDocument2 pagesNaming: Aphasia Screening TestSidra JavedNo ratings yet

- LeadershipDocument24 pagesLeadershipSalman ShahzadNo ratings yet

- Standard of Professional Practice (SPP) On Fulltime Supervision Services SPP Document 204-ADocument4 pagesStandard of Professional Practice (SPP) On Fulltime Supervision Services SPP Document 204-AEugene EscavecheNo ratings yet

- App Id 420 Zipcode Us PsDocument3 pagesApp Id 420 Zipcode Us Pstrujillo66@yahooNo ratings yet

- LC M11 12SP-IVa-1Document20 pagesLC M11 12SP-IVa-1Jean S. FraserNo ratings yet

- Company Profile Intrafood Citarasa Nusantara PDFDocument24 pagesCompany Profile Intrafood Citarasa Nusantara PDFdann yanuar50% (2)

- Taping Over Even and Uneven GroundDocument4 pagesTaping Over Even and Uneven GroundLhizel Llaneta ClaveriaNo ratings yet

- Xerox 5225 Service Mode Qrn20Document4 pagesXerox 5225 Service Mode Qrn20อัมรินทร์ภัคสิริจุฑานันท์No ratings yet

- TIM 40 Instruction BookDocument44 pagesTIM 40 Instruction BookMarkus SenojNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1. Phonetics As A ScienceDocument8 pagesLecture 1. Phonetics As A ScienceInnaNo ratings yet

- Writing To PersuadeDocument10 pagesWriting To Persuadeshumaila parveenNo ratings yet

- Module Csc211Document12 pagesModule Csc211happy dacasinNo ratings yet

- 320 0298E MRM API SpecificationDocument31 pages320 0298E MRM API SpecificationPhani Krishna PNo ratings yet

- Inverter Based DGDocument6 pagesInverter Based DGhassanNo ratings yet

- Database AdministratorDocument17 pagesDatabase AdministratorJustine Joyce GabiaNo ratings yet

- CT4 Models PDFDocument6 pagesCT4 Models PDFVignesh Srinivasan0% (1)

- Weblogicadminmanagedserversautomaticmigration 130324181906 Phpapp01 PDFDocument12 pagesWeblogicadminmanagedserversautomaticmigration 130324181906 Phpapp01 PDFSai KadharNo ratings yet

- A Jungian Study ofDocument3 pagesA Jungian Study ofDr-Mubashar AltafNo ratings yet

- Zarei Et Al. - 2023 - Cooperation, Coordination, or Collaboration A STRDocument24 pagesZarei Et Al. - 2023 - Cooperation, Coordination, or Collaboration A STRmjobs247No ratings yet

- Saudi Aramco Test Report: Calibration Test Report - Pressure Gauge SATR-A-2002 22-Jan-18 MechDocument2 pagesSaudi Aramco Test Report: Calibration Test Report - Pressure Gauge SATR-A-2002 22-Jan-18 MechaneeshNo ratings yet

- CEHv6 Module 01 Introduction To Ethical HackingDocument69 pagesCEHv6 Module 01 Introduction To Ethical HackingfaliqulaminNo ratings yet

- Dimensional Tolerances - ISO3302-1.pdf - International Organization For Standardization - Engineering ToleranceDocument6 pagesDimensional Tolerances - ISO3302-1.pdf - International Organization For Standardization - Engineering Toleranceiceschel100% (1)

- Fiitjee NsejsDocument9 pagesFiitjee NsejsRushdoon AhmedNo ratings yet

- SNT Notes 2022Document7 pagesSNT Notes 2022OrlinNo ratings yet

- Gaseous State Theory - EDocument34 pagesGaseous State Theory - Ethinkiit67% (3)

- BiocideDocument10 pagesBiocidemeratiNo ratings yet

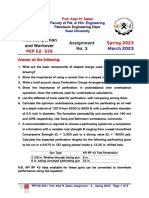

- Assignment No. 3 - PEP E2 335 - Spring 2023Document2 pagesAssignment No. 3 - PEP E2 335 - Spring 2023Dr-Adel SalemNo ratings yet

- F20 User ManualDocument101 pagesF20 User ManualSevim KorkmazNo ratings yet

- Talent ManagementDocument8 pagesTalent ManagementAnthony Dela TorreNo ratings yet