Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Research

Uploaded by

firuzz1Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

Uploaded by

firuzz1Copyright:

Available Formats

Open Access

Research

Prevalence and factors associated with metabolic syndrome in an urban

population of adults living with HIV in Nairobi, Kenya

Catherine Nduku Kiama1,2,&, Joyce Njeri Wamicwe3, Elvis Omondi Oyugi2, Mark Odhiambo Obonyo2, Jane Githuku Mungai2, Zeinab

Gura Roka2, Ann Mwangi1

1

Moi University School of Public Health, Eldoret, Kenya, 2Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, Ministry of Health, Nairobi,

Kenya, 3National AIDS and STI Control Program, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

&

Corresponding author: Catherine Nduku Kiama, Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program, Ministry of Health, Nairobi, Kenya

Key words: Metabolic syndrome, prevalence, associated factors, HIV

Received: 12/07/2017 - Accepted: 06/12/2017 - Published: 30/01/2018

Abstract

Introduction: Metabolic syndrome affects 20-25% of the adult population globally. It predisposes to cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes.

Studies in other countries suggest a high prevalence of metabolic syndrome among HIV-infected patients but no studies have been reported in

Kenya. The objective of this study was to assess the prevalence and factors associated with metabolic syndrome in adult HIV-infected patients in

an urban population in Nairobi, Kenya. Methods: in a cross-sectional study design, conducted at Riruta Health Centre in 2016, 360 adults infected

with HIV were recruited. A structured questionnaire was used to collect data on socio-demography. Blood was collected by finger prick for fasting

glucose and venous sampling for lipid profile. Results: Using the harmonized Joint Scientific Statement criteria, metabolic syndrome was present

in 19.2%. The prevalence was higher among females than males (20.7% vs. 16.0%). Obesity (AOR = 5.37, P < 0.001), lack of formal education

(AOR = 5.20, P = 0.002) and family history of hypertension (AOR = 2.06, P = 0.029) were associated with increased odds of metabolic syndrome

while physical activity (AOR = 0.28, P = 0.001) was associated with decreased odds. Conclusion: Metabolic syndrome is prevalent in this study

population. Obesity, lack of formal education, family history of hypertension, and physical inactivity are associated with metabolic syndrome.

Screening for risk factors, promotion of healthy lifestyle, and nutrition counselling should be offered routinely in HIV care and treatment clinics.

Pan African Medical Journal. 2018; 90:90 doi:10.11604/pamj.2018.29.90.13328

This article is available online at: http://www.panafrican-med-journal.com/content/article/29/90/full/

© Catherine Nduku Kiama et al. The Pan African Medical Journal - ISSN 1937-8688. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original

work is properly cited.

Pan African Medical Journal – ISSN: 1937- 8688 (www.panafrican-med-journal.com)

Published in partnership with the African Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET). (www.afenet.net)

Page number not for citation purposes 1

Introduction 100 HIV patients, on average, per day. We first allocated each

patient a number from 1 to 100 and since we needed to enroll at

least 20 patients per day, we selected every fifth patient to be

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of risk factors in an individual that

included in the study until the required sample size was reached.

increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease and Type 2

With the help of the ART clinic staff, the selected patient was

diabetes [1-3]. Patients with metabolic syndrome are more likely to

contacted on phone and advised to have supper as the last meal

suffer heart attack, stroke and cardiovascular mortality [4-7]. The

and skip breakfast on the clinic visit day in order to collect some

global burden of cardiovascular disease and diabetes is increasing,

blood for tests.

with the biggest burden in lower and middle income countries. This

is expected to rise substantially over the next two decades [8].

Operational definitions: metabolic syndrome was defined

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and use of antiretroviral

according to the harmonized Joint Scientific Statement criteria [23],

treatment (ART) has led to an increase in cases of metabolic

which is the presence of any three of the five following risk factors;

syndrome. HIV natural progression of disease is known to cause

(1) waist circumference > 94cm for men or > 80cm for women, (2)

lipid abnormalities [9]. ART has resulted in improved quality of life,

triglycerides > 1.7 mmol/L or specific treatment for this abnormality,

survival to older ages for those living with HIV and emergence of

(3) HDL-Cholesterol < 1.03 mmol/L for men or < 1.29 mmol/L for

metabolic adverse events related to use of ART; dyslipidemia,

women or specific treatment for this abnormality, (4) elevated blood

changes in body composition, insulin resistance and glucose

pressure > 130/85 mmHg or treatment of previously diagnosed

intolerance [10-12]. Prospective analysis of patients initiated on ART

hypertension and (5) elevated fasting glucose > 5.6 mmol/L or

demonstrated 8.4% increase in prevalence of metabolic syndrome

treatment of previously diagnosed diabetes. Waist circumference

at 48 weeks of antiretroviral treatment [13]. It is estimated that 20-

was used to detect presence of abdominal obesity by measuring

25% of adults globally have metabolic syndrome [14]. Prevalence in

abdominal fat.

sub-Saharan Africa ranges from 0 -50% or higher and differs from

population to population [15, 16]. Studies conducted in the general

Data collection: The questionnaire was prepared in English. The

population from urban centres in Kenya reported the prevalence as

clinician attending to the patient confirmed that the patient had

25.6% (several urban centres) and 34.6% (one urban centre)

supper as their last meal, obtained informed consent and

[17, 18]. Among people living with HIV (PLHIV), studies conducted

administered the questionnaire. We collected socio-demographic

in several African countries report prevalence of up to 60.6% [19-

and risk factor information through face to face interviews. The

22]. According to the 2014 Kenya HIV Estimates Report, Kenya has

socio-demographic variables collected were; age, gender, highest

1.6 million PLHIV and 101,900 new HIV infections annually. There is

level of education, marital status, religion, occupation and

limited data on metabolic syndrome in this population in Kenya

residence. Risk factor information collected were; family history (of

since screening at the ART clinics is not conducted routinely. The

hypertension, diabetes, asthma, cancers, cardiovascular disease),

burden of metabolic syndrome among PLHIV in Kenya is not well

previous diagnosis (of diabetes, hypertension, lipid abnormalities),

understood. We sought to find out the differences in socio-

physical inactivity, fast food diet, stress, obesity, smoking and

demographics and risk factors between the HIV-infected patients

alcohol use. The clinician also carried out the physical examination

with metabolic syndrome and those without the syndrome. The aim

and abstracted clinical information from the patients' files. Clinical

of the study was to assess the prevalence and factors associated

information collected included; WHO staging of HIV disease, history

with metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients in a

of ART use, number of years on ART and last CD4 count. At the end

predominantly urban population in Nairobi, Kenya.

of the visit, blood sugar testing was performed by the clinician at

the point of care according to the Accu-Check glucometer

manufacturer's specifications. About 4.5 mls of venous blood was

Methods collected from the patients at the facility laboratory by a trained

phlebotomist, labelled with a unique number, age and sex and then

Study design and study population : This was a hospital based shipped to the National Public Health Laboratory for lipid profile

cross-sectional study. The study population was sampled HIV testing. Lipid profile testing was done using the Cobas C111

positive patients attending the Riruta Health centre ART clinic. The analyzer. At the end of each day, data was entered into Epi info

eligibility criteria for the study participants were; patients aged ≥18 v.7.14 (CDC TM) and stored in Microsoft Access database on a

years, visiting the ART clinic with a scheduled appointment for personal computer.

routine follow up, enrolled in care (either on prophylaxis or ART) at

least 6 months prior to the study and fasted overnight (for 12 Data analysis: The data was analyzed using Epi info v.7.14 (CDC

hours). We excluded clients with missing medical records, those on TM) software. Univariate analysis was performed and descriptive

interrupted treatment, those visiting due to an acute illness and statistics reported using frequency distribution, proportions and

pregnant women. The Health centre serves as an outpatient facility means for socio-demographic and clinical variables. The prevalence

offering HIV care and treatment amongst other services. It is of metabolic syndrome (95% Confidence Interval) was determined

situated in Dagoretti within the capital city of Nairobi and serves a based on the definition criteria used in the study. Descriptive

predominantly urban population. It is considered a high volume HIV statistics were summarized for females and males to test if there

care and treatment site with an average of 100 HIV-infected was a statistical difference between the two groups. Bivariate

patients scheduled for a clinic visit each day and a total of 3,027 analysis of risk factors undertaken using Odds Ratio as a measure of

patients active and on follow up at the start of the study. The study association and the statistical significance checked using Confidence

was conducted between May and June 2016. Interval and Chi square test with P < 0.05 considered statistically

significant. Binary logistic regression using the forward additive

Sample size calculation and selection of study participants: method was performed to identify the risk factors and to measure

A sample size of 348 was estimated using Cochran's formula (1977) the variation in association between the independent and dependent

with the following assumptions; 34.6% prevalence of metabolic variables. Factors with P < 0.25 from bivariate analysis were

syndrome among the general population in Nairobi [7], 5% included in logistic regression to arrive at the final model of

precision and a 95% confidence interval. The study participants independent predictors of metabolic syndrome.

were selected using random systematic sampling of HIV-infected

patients attending routine clinic visits. The Health centre receives

Page number not for citation purposes 2

Ethical considerations: Written informed consent was obtained similar studies conducted in Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia and Australia

from all the study participants. The study protocol was reviewed and [18, 20, 21, 24]. The higher prevalence in older age-groups is

approved by Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital Institutional Ethics supported by the fact that ageing has been shown to have a causal

and Research Committee (Approval No. 0001531). effect in metabolic syndrome [1]. Abdominal obesity, low HDL-

cholesterol and hypertension were the most prevalent components

in this urban population of HIV-infected persons. Abdominal obesity

Results was present in over half while hypertension and low HDL-cholesterol

in over one third of the study participants. Similarly, a study

conducted among HIV-infected patients in Tanzania reported high

A total of 360 patients were recruited with 66.9% being female

prevalence of abdominal obesity (52.5%), low HDL-cholesterol

(Table 1). Using the harmonized Joint Scientific Statement criteria,

(85.9%) and hypertension (49.2%) [20]. The high prevalence of

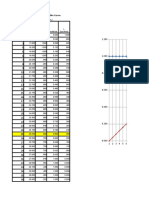

the overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome was 19.2% (95% C.I

these components suggests that there are many patients with

15.3-23.7), higher in females than males. There was no case of

precursors for metabolic syndrome. This presents an opportunity to

metabolic syndrome observed among patients aged 18-24 years.

delay development of cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes if

The prevalence increased with age with patients older than 55 years

early cardiovascular risk assessment is offered with lifestyle

having the highest prevalence (Figure 1). The prevalence of

modification for those identified to be at risk [1].

metabolic syndrome components in our study participants was;

abdominal obesity 51.1%, low HDL-Cholesterol 32.5%, systolic

Abdominal obesity and low HDL-Cholesterol were more prevalent

hypertension 32.5%, hyperglycaemia 21.4% and

among the female patients while hypertriglyceridemia, hypertension

hypertriglyceridemia 14.2%. The prevalence of abdominal obesity

and hyperglycaemia were more prevalent among the males. The

and low HDL-Cholesterol was higher among the female patients.

prevalence of the individual components of metabolic syndrome by

However, the prevalence of hypertension, hyperglycaemia and

gender was consistent with figures reported in Tanzania and South

hypertriglyceridemia was higher among the male patients (Table 2).

Africa [20, 22]. Similarly, gender differences were also observed in

There were either few or no patients aged 18-24 years with any of

an urban general population in Nairobi, Kenya [18]. The observed

the metabolic syndrome components. On bivariate analysis, obesity

gender differences in the prevalence of the individual components in

(BMI > 30kg/m2), informal education, age ≥ 45 years and family

this population could be attributed to hormonal and biological

history of hypertension were associated with increased odds of

factors [1]. Obesity, lack of formal education, ages > 55 years and

metabolic syndrome. Patients on antiretroviral treatment and those

family history of hypertension increased the likelihood of metabolic

who were physically active had decreased odds of metabolic

syndrome. Obesity is a known modifiable risk factor for metabolic

syndrome. Metabolic syndrome was not associated with gender,

syndrome [1, 28]. Having attained secondary or tertiary level

employment status, history of cardiovascular disease and diabetes

education was found to be protective (OR = 0.3, P = 0.012) of

in the family, smoking, alcohol use, consumption of fast foods and

metabolic syndrome in the general population in Kenya [18]. Ageing

stress (Table 3). On multivariate analysis, there was a positive

has been shown to have a causal effect in metabolic syndrome [1].

association between obesity, lack of formal education, family history

There was an increased likelihood of metabolic syndrome in older

of hypertension and occurrence of metabolic syndrome. Patients

study participants drawn from the urban general population in

who were physically active had reduced odds of having metabolic

Kenya [18]. Heredity and genetics have been shown to have a

syndrome (Table 4).

causal effect in metabolic syndrome [1]. The study also showed that

physical activity and ART reduce likelihood of metabolic syndrome.

Studies have shown that physical inactivity and a sedentary lifestyle

Discussion predispose to metabolic syndrome [1, 29]. The finding on ART

should be interpreted with caution since the number of patients not

The study revealed that metabolic syndrome is prevalent among on ART (n = 5) in the study was small. A possible explanation for

HIV-infected patients. The study prevalence is similar to that the small number of patients not on ART is that Kenya as a country

reported among HIV-infected patients using the same criteria in has moved towards the test and treat approach where all HIV-

other countries; Australia (14%), Spain (16%), Barcelona (17%) infected patients are initiated on ART irrespective of the CD4 count.

and Ethiopia (21.1%) [13, 21, 24, 25]. The study prevalence was However, it is possible that the patients who were on ART in our

however much lower than the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in study had received nutrition counselling and lifestyle modification

HIV-infected patients in Tanzania (25.6%), Denmark (27%), advice during the health talks and psychosocial support group

Cameroon (32.8%), Portugal (41.9%) and South Africa (60.6%) meetings at the treatment facility hence ART appears protective in

[19, 20, 22, 26, 27]. The study prevalence is also lower than the this population. In contrast, other studies have demonstrated that

34.6% and 25.6% prevalence reported among the general ART leads to increased survival of HIV patients, improved quality of

population living in urban centres in Kenya in 2012 and 2017 life and metabolic complications as adverse effects in patients

respectively [17, 18]. The presence of metabolic syndrome in HIV- receiving ART [22, 28, 30]. In another prospective cohort study,

infected patients puts them at an increased risk of developing ART was shown to increase the prevalence of metabolic syndrome

cardiovascular disease and Type 2 diabetes [14, 15, 17]. This poses from 16.6% to 25% after 48 weeks of the study population

a higher risk of associated cardiovascular morbidity and mortality receiving the treatment [13]. Our study had limitations. We could

among HIV-infected patients in addition to opportunistic infections not establish causal association or the temporal sequence of events

that they are predisposed to [24]. The study found that there were since this was a cross-sectional study. Fasting blood sugar and lipid

gender differences in prevalence of metabolic syndrome with a profile testing was based on self-report of having fasted for 12

higher prevalence observed among female patients. Other studies hours, there is possible misclassification of glycaemia and lipid

have reported higher prevalence among females; 44.4 vs. 9.9% in profile abnormalities with potential to interpret random blood

Cameroon, and 25 vs. 12% in Australia [12, 17]. The observed specimens as fasted states. However, this does not affect

higher prevalence among females in this population could be due to assessment of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome or factors

biological, hormonal and environmental factors that are thought to associated with the syndrome among HIV-infected patients.

be contributing to occurrence of metabolic syndrome in women [1].

The prevalence was higher with increasing age and highest among

those aged > 55 years. This observation has been reported in other

Page number not for citation purposes 3

Conclusion Tables and figure

Metabolic syndrome is prevalent among HIV-infected persons. The Table 1: Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of adult

high prevalence of abdominal obesity, dyslipidemia and HIV-infected patients, Riruta Health Centre, 2016

hypertension suggests that there are many HIV-infected patients Table 2: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome components among

with precursors for metabolic syndrome. Obesity, lack of formal adult HIV-infected patients, Riruta Health Centre, 2016

education, family history of hypertension, and physical inactivity are Table 3: Bivariate analysis of risk factors for metabolic syndrome in

associated with metabolic syndrome. Screening for risk factors, adult HIV-infected patients, Riruta Health Centre, 2016

promotion of healthy lifestyle, and nutrition counselling should be Table 4: Final logistic regression model of factors associated with

offered routinely in HIV care and treatment clinics. metabolic syndrome among adult HIV-infected patients, Riruta

Health Centre, 2016

What is known about this topic Figure 1: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adult HIV-

infected patients by gender and age-group, Riruta Health Centre,

Metabolic syndrome is known to be prevalent among HIV 2016

infected persons in other countries with prevalence of up

to 60% reported;

People living with HIV are predisposed to metabolic References

syndrome due to the metabolic complications that are

associated with long term use of antiretroviral treatment; 1. Alberti KGMM, Zimmet P, Shaw J. Metabolic syndrome: a new

Screening for non-communicable diseases is not world-wide definition: a consensus statement from the

prioritised in HIV care settings. international diabetes federation. Diabet Med J Br Diabet

Assoc. 2006 May; 23(5): 469-80. PubMed | Google Scholar

What this study adds

2. Alshehri AM. Metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk. J

Screening for metabolic syndrome can be integrated into Fam Community Med. 2010 Aug; 17(2): 73.PubMed | Google

routine services offered at HIV care and treatment centres Scholar

with minimal resources;

3. Fox CS. Cardiovascular disease risk factors, Type 2 Diabetes

Metabolic syndrome, abdominal obesity and hypertension

Mellitus, and the Framingham Heart Study. Trends Cardiovasc

is prevalent among the adult HIV-infected persons living

Med. 2010 Apr; 20(3): 90. PubMed | Google Scholar

in an urban town in Kenya with prevalence increasing with

older ages;

4. Hu G, Qiao Q, Tuomilehto J, Balkau B, Borch-Johnsen K,

Metabolic syndrome in HIV is associated with level of Pyorala K. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome and its

education, family history of hypertension, obesity and relation to all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Nondiabetic

physical activity. European Men and Women. Arch Intern Med. 2004 May 24;

164(10): 1066-76. PubMed | Google Scholar

Competing interests 5. Isomaa B, Almgren P, Tuomi T, Forsén B, Lahti K, Nissén M et

al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the

The authors declare no competing interests. metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001 Apr 1; 24(4):

683?9. PubMed | Google Scholar

6. Lakka H-M, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, Niskanen LK, Kumpusalo

Authors’ contributions E, Tuomilehto J et al. The metabolic syndrome and total and

cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA.

Catherine Kiama participated in the study design, ethical approval, 2002 Dec 4; 288(21): 2709-16. PubMed | Google Scholar

data collection, data analysis and manuscript writing. Joyce

Wamicwe, Mark Obonyo, Elvis Oyugi and Jane Mungai contributed 7. Stern MP, Williams K, González-Villalpando C, Hunt KJ, Haffner

in revision of manuscript. Zeinab Gura and Ann Mwangi contributed SM. Does the Metabolic Syndrome Improve Identification of

towards the review of data and critical appraisal of manuscript. All Individuals at Risk of Type 2 Diabetes and/or Cardiovascular

authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript. Disease. Diabetes Care. 2004 Nov 1; 27(11): 2676-

81. PubMed | Google Scholar

Acknowledgments 8. World Health Organization. Global action plan for the

prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases:

This study was financially supported by the Field Epidemiology and 2013-2020. Accessed on July 10 2017.

Laboratory Training Program (FELTP-Kenya). I wish to express my

sincere gratitude to the study participants, team of data collectors at 9. Grunfeld C, Pang M, Doerrler W, Shigenaga JK, Jensen P,

Riruta Health centre, and the National Public Health Laboratory staff Feingold KR. Lipids, lipoproteins, triglyceride clearance and

for processing the specimens. cytokines in human immunodeficiency virus infection and the

acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

1992 May; 74(5): 1045-52. PubMed | Google Scholar

Page number not for citation purposes 4

10. Carr A, Samaras K, Burton S, Law M, Freund J, Chisholm DJ et 21. Berhane T, Yami A, Alemseged F, Yemane T, Hamza L, Kassim

al. A syndrome of peripheral lipodystrophy, hyperlipidaemia M et al. Prevalence of lipodystrophy and metabolic syndrome

and insulin resistance in patients receiving HIV protease among HIV positive individuals on Highly Active Anti-Retroviral

inhibitors. AIDS Lond Engl. 1998 May 7; 12(7): F51- treatment in Jimma, South West Ethiopia. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;

58. PubMed | Google Scholar 13: 43. PubMed | Google Scholar

11. Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, 22. Erasmus RT, Soita DJ, Hassan MS, Blanco-Blanco E, Vergotine

Satten GA et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among Z, Kegne AP et al. High prevalence of diabetes mellitus and

patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus metabolic syndrome in a South African coloured population:

infection, HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. baseline data of a study in Bellville, Cape Town. South Afr Med

1998 Mar 26; 338(13): 853-60. PubMed | Google Scholar J Suid-Afr Tydskr Vir Geneeskd. 2012 Oct 8;102(11 Pt 1): 841-

4. PubMed | Google Scholar

12. Ete T, Ranabir S, Thongam N, Ningthoujam B, Rajkumar N,

Thongam B. Metabolic abnormalities in human 23. Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI,

immunodeficiency virus patients with protease inhibitor-based Donato KA et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint

therapy. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2014; 35(2): 100- interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation

3. PubMed | Google Scholar Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart,

Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World

13. Palacios R, Santos J, González M, Ruiz J, Márquez M. Incidence Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and

and prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in a cohort of naive International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation.

HIV-infected patients: prospective analysis at 48 weeks of 2009 Oct 20; 120(16): 1640-5. PubMed | Google Scholar

highly active antiretroviral therapy. Int J STD AIDS. 2007 Mar

1; 18(3): 184-7. PubMed | Google Scholar 24. Samaras K, Wand H, Law M, Emery S, Cooper D, Carr A.

Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients

14. Alberti KGM, Zimmet P, Shaw J. The metabolic syndrome: a receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy using International

new worldwide definition. The Lancet. 2005 Sep; 366(9491): Diabetes Foundation and Adult Treatment Panel III criteria:

1059-62. PubMed | Google Scholar associations with insulin resistance, disturbed body fat

compartmentalization, elevated C-reactive protein and

15. Isezuo SA, Ezunu E. Demographic and clinical correlates of [corrected] hypoadiponectinemia. Diabetes Care. 2007 Jan;

metabolic syndrome in Native African type-2 diabetic patients. 30(1): 113-9. PubMed | Google Scholar

J Natl Med Assoc. 2005 Apr; 97(4): 557. PubMed | Google

Scholar 25. Jericó C, Knobel H, Montero M, Ordoñez-Llanos J, Guelar A,

Gimeno JL et al. Metabolic syndrome among HIV-infected

16. Fezeu L, Balkau B, Kengne A-P, Sobngwi E, Mbanya JC. patients: prevalence, characteristics and related factors.

Metabolic syndrome in a sub-Saharan African setting: central Diabetes Care. 2005 Jan; 28(1): 132-7. PubMed | Google

obesity may be the key determinant. Atherosclerosis. 2007 Jul; Scholar

193(1): 70. PubMed |Google Scholar

26. Hansen BR, Petersen J, Haugaard SB, Madsbad S, Obel N,

17. Omuse G, Maina D, Hoffman M, Mwangi J, Wambua C, Suzuki Y et al. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in

Kagotho E et al. Metabolic syndrome and its predictors in an Danish patients with HIV infection: the effect of antiretroviral

urban population in Kenya: a cross-sectional study. BMC therapy. HIV Med. 2009 Jul 1; 10(6): 378-

Endocr Disord. 2017; 17: 37.Google Scholar 87. PubMed | Google Scholar

18. Kaduka LU, Kombe Y, Kenya E, Kuria E, Bore JK, Bukania ZN et 27. Santos A-C, Barros H. Impact of metabolic syndrome

al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among an urban definitions on prevalence estimates: a study in a Portuguese

population in Kenya. Diabetes Care. 2012 Apr; 35(4): 887- community. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2007 Dec 1; 4(4): 320-

93. PubMed | Google Scholar 7. PubMed | Google Scholar

19. Dimodi HT, Etame LS, Nguimkeng BS, Mbappe FE, Ndoe NE, 28. Paula AA, Falcão MC, Pacheco AG. Metabolic syndrome in HIV-

Tchinda JN et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in HIV- infected individuals: underlying mechanisms and

infected Cameroonian Patients. World J AIDS. 2014; 4: 85- epidemiological aspects. AIDS Res Ther. 2013 Dec 13; 10(1):

92. Google Scholar 32. PubMed | Google Scholar

20. Kagaruki G, Kimaro G, Mweya C, Kilale A, Mrisho R, Shao A et 29. Carr DB, Utzschneider KM, Hull RL, Kodama K, Retzlaff BM,

al. Prevalence and risk factors of metabolic syndrome among Brunzell JD et al. Intra-abdominal fat is a major determinant of

individuals living with HIV and receiving antiretroviral the National Cholesterol Education Program adult treatment

treatment in Tanzania. Br J Med Med Res. 2015 Jan 10; 5(10): panel III criteria for the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2004

1317-27. Google Scholar Aug; 53(8): 2087-94. PubMed | Google Scholar

30. Price J, Hoy J, Ridley E, Nyulasi I, Paul E, Woolley I. Changes

in the prevalence of lipodystrophy, metabolic syndrome and

cardiovascular disease risk in HIV-infected men. Sex Health.

2015 Jun; 12(3): 240-8. PubMed | Google Scholar

Page number not for citation purposes 5

Table 1: Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of adult HIV-infected patients, Riruta

Health Centre, 2016

Combined Female Male

Characteristic p-value

No. (%) No. (%) No. (%)

N 360 241 119

Age-group (years)

18-24 11 (3.1) 9 (81.8) 2 (18.2) 0.285

25-34 90 (25.0) 72 (80.0) 18 (20.0) 0.002

35-44 126 (35.0) 85 (67.5) 41 (32.5) 0.881

45-54 101 (28.1) 57 (56.4) 44 (43.6) 0.008

>55 32 (9.9) 18 (56.2) 14 (43.8) 0.177

Highest level of education

No education 18 (5.0) 15 (83.3) 3 (16.7) 0.129

Primary incomplete 82 (22.8) 61 (74.4) 21 (25.6) 0.103

Primary complete 109 (30.3) 75 (68.8) 34 (31.2) 0.617

Secondary/ Tertiary 151 (41.9) 90 (59.6) 61 (40.4) 0.012

Marital status

Never Married 37 (10.3) 31 (83.8) 6 (16.2) 0.021

Married 190 (52.8) 93 (48.9) 97 (51.1) <0.001

Living together/Cohabiting 5 (1.4) 5 (100.0) 0 (0.0) 0.114

Divorced/ Separated 80 (22.2) 70 (87.5) 10 (12.5) <0.001

Widowed 48 (13.3) 42 (87.5) 6 (12.5) 0.001

Religion

Muslim 9 (2.5) 7 (80.0) 0 (0.0) 0.060

Protestant/ Other Christian 266 (73.9) 186 (69.9) 80 (30.1) 0.043

Roman Catholic 75 (20.8) 42 (56.0) 33 (44.0) 0.024

No religion 4 (1.1) 0 (0.0) 4 (100.0) 0.004

Other 6 (1.7) 6 (100.0) 0 (0.0) 0.082

Occupation

Employed/Self Employed 198 (55.0) 125 (63.1) 73 (36.9) 0.089

Student 3 (0.8) 2 (66.7) 1 (33.3) 0.992

Unemployed 54 (15.0) 48 (88.9) 6 (11.1) <0.001

Unskilled labor 105 (29.2) 66 (62.3) 39 (37.7) 0.289

Residence

Rural 3 (0.8) 1 (33.3) 2 (66.7) 0.215

Urban 357 (99.2) 240 (67.2) 117 (32.8) 0.215

On Antiretroviral treatment

(ART)

Yes 355 (98.6) 236 (66.5) 119 (33.5) 0.114

No 5 (1.4) 5 (100.0) 0 (0.0) 0.114

WHO stage

1 334 (92.8) 221 (66.2) 113 (33.8) 0.263

2 7 (1.9) 6 (85.7) 1 (14.3) 0.285

3 6 (1.7) 4 (66.7) 2 (33.3) 0.992

4 1 (0.3) 1 (100.0) 0 (0.0) 0.484

Number of years on ART

4.5 ± 3.2 4.5 ± 3.1 4.6 ± 3.4 0.781

mean ± SD

393.2

CD4 Count mean ± SD 357.8 ± 223.6 286.5 ±179.6 <0.0001

± 234.9

A total of 12 patients (3.3%): 9 female and 3 male did not have a WHO stage recorded in their

files

Page number not for citation purposes 6

Table 2: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome components among adult HIV-infected patients,

Riruta Health Centre, 2016

Metabolic syndrome Combined Female Male

p-value

components No. (%) No. (%) No. (%)

N 360 241 119

Metabolic syndrome 69 (19.2) 50 (20.7) 19 (16.0) 0.280

High waist circumference 184 (51.1) 141 (58.5) 43 (36.1) < 0.001

Low HDL – Cholesterol 117 (32.5) 88 (36.5) 29 (24.4) 0.021

Systolic Blood pressure ≥

117 (32.5) 71 (29.5) 46 (38.7) 0.080

130mmHg

Glycaemia ≥ 5.6 mmol/L 77 (21.4) 50 (20.7) 27 (22.7) 0.675

Triglycerides ≥ 1.7 mmol/L 51 (14.2) 31 (12.9) 20 (16.8) 0.313

Waist circumference cut off ≥ 94 cm for men or ≥ 80 cm for women

Low HDL – Cholesterol was defined as < 1.03 for men or < 1.29mmol/L for women

Page number not for citation purposes 7

Table 3: Bivariate analysis of risk factors for metabolic syndrome in adult HIV-infected patients, Riruta Health Centre, 2016

With metabolic Without metabolic

Crude OR

Factors Syndrome syndrome p-value

(95% C.I)

n = 69 n = 291

Female

Yes 50 191 1.38 (0.77 – 2.46) 0.278

No 19 100

≥ 45 years

Yes 37 96 2.35 (1.38 – 4.00) 0.001

No 32 195

Informal employment

Yes 64 5 2.53 (0.97 – 6.61) 0.058

No 243 48

Informal education

Yes 9 9 4.70 (1.79 – 12.34) < 0.001

No 60 282

On Antiretroviral treatment

Yes 66 289 0.15 (0.02 – 0.93) 0.051

No 3 2

Family history of

cardiovascular disease

Yes 5 10 2.20 (0.73 – 6.64) 0.154

No 64 281

Family history of diabetes

mellitus

Yes 14 49 1.26 (0.65 – 2.44) 0.498

No 55 242

Family history of hypertension

Yes 25 63 2.06 (1.17 – 3.62) 0.011

No 44 228

History of smoking

Yes 6 36 0.675 (0.27 – 1.67) 0.393

No 63 255

Alcohol use

Yes 6 22 1.16 (0.45 – 2.99) 0.752

No 63 269

Physical activity

Yes 10 115 0.26 (0.13 – 0.53) < 0.001

No 59 176

Eating fast foods

Yes 36 145 1.10 (0.65 – 1.86) 0.726

No 33 146

Stress

Yes 30 126 1.00 (0.59 – 1.71) 0.978

No 39 165

Obesity

Yes 27 32 5.20 (2.84 – 9.55) < 0.001

No 42 259

Table 4:Final logistic regression model of factors associated with metabolic syndrome among adult HIV-infected patients, Riruta Health Centre, 2016

Factor Adjusted Odds Ratio 95% C.I p-value

Obesity (BMI > 30kg/m2) 5.37 2.80 – 10.27 < 0.001

Informal education 5.20 1.84 – 14.64 0.0018

Family history of hypertension 2.06 1.07 – 3.94 0.0299

Physical activity 0.28 0.13 – 0.60 0.0010

Eight factors were entered into the forward additive logistic regression model; obesity, physical activity, informal education, age, family history of

hypertension, on antiretroviral treatment, informal employment and family history of cardiovascular disease

Page number not for citation purposes 8

Figure 1: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome among adult HIV-infected patients by gender and age-group, Riruta Health Centre, 2016

Page number not for citation purposes 9

You might also like

- Fast Facts: Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Translating the science into compassionate IBD careFrom EverandFast Facts: Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Translating the science into compassionate IBD careNo ratings yet

- 10 11648 J CCR 20200403 15Document7 pages10 11648 J CCR 20200403 15NjeodoNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Clinical GuideFrom EverandDiagnosis and Management of Autoimmune Hepatitis: A Clinical GuideMark W. RussoNo ratings yet

- Nafld Global PrevalenceDocument12 pagesNafld Global PrevalenceSvt Mscofficial2No ratings yet

- Jurnal JantungDocument10 pagesJurnal Jantunglukas mansnandifuNo ratings yet

- 7 - Health Seeking Behaviour and Perception of Quality of CareDocument6 pages7 - Health Seeking Behaviour and Perception of Quality of CareSunday AyamolowoNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Final DraftDocument110 pagesResearch Proposal Final Draftapi-549811354No ratings yet

- 5 Prevalence and Risk ChinaDocument16 pages5 Prevalence and Risk ChinaM JNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0171987Document9 pagesJournal Pone 0171987Maulida HalimahNo ratings yet

- Editorial: "Treat 3 Million People Living With Hiv/Aids by 2005"Document3 pagesEditorial: "Treat 3 Million People Living With Hiv/Aids by 2005"Praneeth Raj PatelNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome Among An Urban Population in KenyaDocument7 pagesPrevalence of Metabolic Syndrome Among An Urban Population in KenyaMutia UlfaNo ratings yet

- International Incidence and Mortality Trends of Liver Cancer: A Global ProfileDocument9 pagesInternational Incidence and Mortality Trends of Liver Cancer: A Global ProfileNovita ApramadhaNo ratings yet

- Comparative Study of Isolates Associated With Urinary Tract Infection Among Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients Attending Tertiary Care Hospital, Chitwan, NepalDocument11 pagesComparative Study of Isolates Associated With Urinary Tract Infection Among Diabetic and Non-Diabetic Patients Attending Tertiary Care Hospital, Chitwan, NepalInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Anemia2014 108593Document9 pagesAnemia2014 108593AaronMaroonFive100% (1)

- Prevalence and Major Risk Factors of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Cross-Sectional Study in EcuadorDocument5 pagesPrevalence and Major Risk Factors of Diabetic Retinopathy: A Cross-Sectional Study in EcuadorJorge Andres Talledo DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Risk Factors For ChronicDocument10 pagesPrevalence and Risk Factors For ChronicKhoirul AnamNo ratings yet

- Internal Medicine Journal - 2017 - Fernando - Healthcare Acquired Infections Prevention StrategiesDocument11 pagesInternal Medicine Journal - 2017 - Fernando - Healthcare Acquired Infections Prevention StrategiesMimi ElagoriNo ratings yet

- 11 The Epidemiology of Intestinal MicrosporidiosisDocument7 pages11 The Epidemiology of Intestinal MicrosporidiosisDaniel VargasNo ratings yet

- Global Burden of NAFLD and NASHDocument33 pagesGlobal Burden of NAFLD and NASHMohammad Hadi SahebiNo ratings yet

- 107,838,255 Confirmed Cases 2,373,398 Deaths Cases: Recovered: DeathsDocument17 pages107,838,255 Confirmed Cases 2,373,398 Deaths Cases: Recovered: DeathsrheesNo ratings yet

- Patient Awareness, Prevalence, and Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease Among Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertensive PatientsDocument9 pagesPatient Awareness, Prevalence, and Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease Among Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertensive Patientsnurul niqmahNo ratings yet

- Manejo de Neoplasia Intraepitelial AnalDocument10 pagesManejo de Neoplasia Intraepitelial AnalLibertad DíazNo ratings yet

- Antituberculosis Drug-Induced Liver Injury: An Ignored Fact, Assessment of Frequency, Patterns, Severity and Risk FactorsDocument12 pagesAntituberculosis Drug-Induced Liver Injury: An Ignored Fact, Assessment of Frequency, Patterns, Severity and Risk FactorsDrAkhtar SultanNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Intervention and Cholecystectomy in Pregnant Women With Acute Biliary Pancreatitis Decreases Early ReadmissionsDocument19 pagesEndoscopic Intervention and Cholecystectomy in Pregnant Women With Acute Biliary Pancreatitis Decreases Early ReadmissionsCarlos Altez FernandezNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Among HIV-Infected Patients On Antiretroviral Therapy at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Central UgandaDocument6 pagesDiabetes Among HIV-Infected Patients On Antiretroviral Therapy at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Central UgandaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 1Document7 pagesJurnal 1ida ayu agung WijayantiNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Adults: Present and FutureDocument15 pagesReview Article: Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis in Adults: Present and FutureEsha TwinkleNo ratings yet

- 17 Malenica 920 ADocument7 pages17 Malenica 920 AqiraniNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases and Metabolic SyndromeDocument9 pagesRisk Factors of Non-Communicable Diseases and Metabolic SyndromeAseem MohammedNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Real World Data From A Large US Claims DatabaseDocument27 pagesHealthcare Cost and Utilization in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Real World Data From A Large US Claims DatabaseAnonymous Xx62oL0diMNo ratings yet

- Cancers 14 02230 v2Document12 pagesCancers 14 02230 v2bisak.j.adelaNo ratings yet

- Epidemi IbdDocument9 pagesEpidemi IbdShanaz NovriandinaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Outcome of Donors PDFDocument7 pagesClinical Outcome of Donors PDFEngidaNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy Failure Amongst HIV-Infected African Patients: A Case-Control StudyDocument8 pagesFactors Associated With First-Line Antiretroviral Therapy Failure Amongst HIV-Infected African Patients: A Case-Control Studymeriza dahlia putriNo ratings yet

- Time To Step Up The Fight Against NAFLDDocument4 pagesTime To Step Up The Fight Against NAFLDAnonymous wIWNHdPVGNo ratings yet

- ciz284 ٠٥٠٧٣٤Document9 pagesciz284 ٠٥٠٧٣٤ضبيان فرحانNo ratings yet

- Inflammatory Potential of Diet and Risk of Colorectal Cancer A Casecontrol Study From ItalyDocument7 pagesInflammatory Potential of Diet and Risk of Colorectal Cancer A Casecontrol Study From ItalyHenrique VidalNo ratings yet

- Ojcr MS Id 000538-1Document7 pagesOjcr MS Id 000538-1NjeodoNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Among HIV-Infected Patients On Antiretroviral Therapy at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Central UgandaDocument6 pagesDiabetes Among HIV-Infected Patients On Antiretroviral Therapy at Mulago National Referral Hospital in Central UgandaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Anemia Prevalence, Severity Level and Its Predictors Among Antenatal Care Attending Pregnant Women in Butajira General Hospital Southern EthiopiaDocument9 pagesAnemia Prevalence, Severity Level and Its Predictors Among Antenatal Care Attending Pregnant Women in Butajira General Hospital Southern EthiopiaJournal of Nutritional Science and Healthy DietNo ratings yet

- CHD and MalnutDocument9 pagesCHD and MalnutMuhammad AfifNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Mellitus and Pyogenic Liver Abscess: Risk and PrognosisDocument8 pagesDiabetes Mellitus and Pyogenic Liver Abscess: Risk and PrognosisJeanetteNo ratings yet

- Retensi UrinDocument13 pagesRetensi UrinSulhan SulhanNo ratings yet

- Bmjopen 2011 000666Document6 pagesBmjopen 2011 000666Fabiola PortugalNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Factors Associated With Prediabetes and Diabetes Mellitus in Kenya - Results From A National SurveyDocument11 pagesPrevalence and Factors Associated With Prediabetes and Diabetes Mellitus in Kenya - Results From A National SurveyPaul MugambiNo ratings yet

- Increased Risk of Hyperlipidemia in BPDDocument5 pagesIncreased Risk of Hyperlipidemia in BPDRebecca SilaenNo ratings yet

- Chronic Liver Disease Epid 2021Document6 pagesChronic Liver Disease Epid 2021Adrian ssNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Infectious DiseasesDocument4 pagesInternational Journal of Infectious DiseasesAgungBudiPamungkasNo ratings yet

- The Prevalence and Determinants of Anaemia in JordanDocument9 pagesThe Prevalence and Determinants of Anaemia in Jordanرجاء خاطرNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Smoking Interact in Relation With Colorectal AdenomasDocument15 pagesNutrients: Ultra-Processed Food Intake and Smoking Interact in Relation With Colorectal AdenomasAndrés Felipe Zapata MurielNo ratings yet

- Asfari 2020 лактозаDocument6 pagesAsfari 2020 лактозаdr.martynchukNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Risk Factors For Ventilator Associated Pneumon 2007 RespiratorDocument6 pagesIncidence and Risk Factors For Ventilator Associated Pneumon 2007 RespiratorTomasNo ratings yet

- Transient Hyperglycemia in Patients With Tuberculosis in Tanzania: Implications For Diabetes Screening AlgorithmsDocument10 pagesTransient Hyperglycemia in Patients With Tuberculosis in Tanzania: Implications For Diabetes Screening AlgorithmsNura RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of The Metabolic Syndrome in Hungary: Public HealthDocument7 pagesEpidemiology of The Metabolic Syndrome in Hungary: Public Healthadi suputraNo ratings yet

- Analgesic Use Parents Clan and Coffee Intake Are Three Independent Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease in Middle and Elderly Aged Population ADocument7 pagesAnalgesic Use Parents Clan and Coffee Intake Are Three Independent Risk Factors of Chronic Kidney Disease in Middle and Elderly Aged Population AJackson HakimNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0160922Document16 pagesJournal Pone 0160922Indah Triana PutriNo ratings yet

- Infection Is Acommonproblem ForDocument11 pagesInfection Is Acommonproblem ForDitaMayasariNo ratings yet

- Medical ScienceDocument6 pagesMedical ScienceRara RabiahNo ratings yet

- Phagocytic ActivityDocument6 pagesPhagocytic Activityeki_herawatiNo ratings yet

- Manual On The PEN Protocol On The Integrated Management of Hypertension and DiabetesDocument61 pagesManual On The PEN Protocol On The Integrated Management of Hypertension and DiabetesRanda Noray100% (2)

- Sertifika TDocument4 pagesSertifika Tfiruzz1No ratings yet

- Correlations: Hasil Validitas Dan ReabilitasDocument10 pagesCorrelations: Hasil Validitas Dan Reabilitasfiruzz1No ratings yet

- InfluenzaDocument1 pageInfluenzafiruzz1No ratings yet

- By: Oriza Nur Barokah Insan Unggul Surabaya Health Science ColledgeDocument8 pagesBy: Oriza Nur Barokah Insan Unggul Surabaya Health Science Colledgefiruzz1No ratings yet

- Shofiya Hanun: Luluk HanifahDocument15 pagesShofiya Hanun: Luluk Hanifahfiruzz1No ratings yet

- InfluenzaDocument1 pageInfluenzafiruzz1No ratings yet

- Cut Off PointDocument8 pagesCut Off Pointfiruzz1No ratings yet

- Bab Ii PboDocument39 pagesBab Ii Pbofiruzz1No ratings yet

- Jurnal HepatitisDocument6 pagesJurnal Hepatitisfiruzz1No ratings yet

- Mahasiswa: 18 October 2016 Universitas Surabaya - To Be The First University in Heart and MindDocument1 pageMahasiswa: 18 October 2016 Universitas Surabaya - To Be The First University in Heart and Mindfiruzz1No ratings yet

- Muslim Scientists and Their Contributions in The Development of ScienceDocument13 pagesMuslim Scientists and Their Contributions in The Development of ScienceWasib KhanNo ratings yet

- VaneDocument16 pagesVanerafaelNo ratings yet

- Pharmacy: Practical ManualDocument84 pagesPharmacy: Practical ManualFAROOQNo ratings yet

- Product ManagerDocument40 pagesProduct ManagerPrashant PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Alveolar Bone GraftingDocument38 pagesAlveolar Bone GraftingMohammed Qasim Al-Watary100% (1)

- IVT ChecklistDocument12 pagesIVT ChecklistCamille Joy Limos Catungal100% (3)

- Medical Outcomes Study: 36-Item Short Form Survey InstrumentDocument3 pagesMedical Outcomes Study: 36-Item Short Form Survey InstrumentBincy Kurian100% (1)

- Moonlighting Policy and Template LTR AY09-10Document4 pagesMoonlighting Policy and Template LTR AY09-10yathrthNo ratings yet

- The Tactical Athlete A Product of 21st Century.2Document6 pagesThe Tactical Athlete A Product of 21st Century.2fggffsdgNo ratings yet

- BPI - Construction and Start-Up Costs For Biomanufacturing PlantsDocument7 pagesBPI - Construction and Start-Up Costs For Biomanufacturing Plantsraju1559405No ratings yet

- Mass+In+A+Flash+2 0Document16 pagesMass+In+A+Flash+2 0rnastaseNo ratings yet

- ENLS Meningitis and Encephalitis ProtocolDocument20 pagesENLS Meningitis and Encephalitis ProtocolFransiskus MikaelNo ratings yet

- Breathing QuestionsDocument21 pagesBreathing QuestionsKahfiantoro100% (1)

- Unilateral BreathingDocument3 pagesUnilateral BreathingJohn Benedict VocalesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Company Profile and General IntroductionDocument61 pagesChapter 1: Company Profile and General IntroductionPRACHI DASNo ratings yet

- NLM Pillbox API Documentation v2 2011.09.27Document7 pagesNLM Pillbox API Documentation v2 2011.09.27Vignesh PTNo ratings yet

- IM Written Report Diabetes Case ReportDocument10 pagesIM Written Report Diabetes Case ReportJessa Mateum VallangcaNo ratings yet

- Behavioral AssessmentDocument21 pagesBehavioral AssessmentManojNo ratings yet

- Anatomy Questions-Limbs-1Document25 pagesAnatomy Questions-Limbs-1Esdras DountioNo ratings yet

- This Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Document4 pagesThis Unit Group Contains The Following Occupations Included On The 2012 Skilled Occupation List (SOL)Abdul Rahim QhurramNo ratings yet

- Rights and Responsibilities of Doctors and Patients: PreambleDocument6 pagesRights and Responsibilities of Doctors and Patients: PreambleYoga EkoNo ratings yet

- AaaaaDocument32 pagesAaaaarats clusterNo ratings yet

- Addictions and Impulse-Control DisordersDocument24 pagesAddictions and Impulse-Control DisordersDalilla MatildeNo ratings yet

- School NursingDocument4 pagesSchool NursingBianca MaeNo ratings yet

- Home Remedies To Improve Eyesight - Top 10 Home RemediesDocument21 pagesHome Remedies To Improve Eyesight - Top 10 Home RemediesKanisetty Janardan100% (1)

- TDCS Montage Reference v1 0 PDF PDFDocument10 pagesTDCS Montage Reference v1 0 PDF PDFPatricio Eduardo Barría AburtoNo ratings yet

- Autism HandbookDocument42 pagesAutism Handbookaqeel142350% (2)

- Job Description of Nursing PersonnelDocument26 pagesJob Description of Nursing PersonnelThilakam Dhanya100% (3)

- Daftar PustakaDocument2 pagesDaftar PustakaKomang Krisnanta SaputraNo ratings yet

- European MP and E Conference - ProceedingsDocument377 pagesEuropean MP and E Conference - ProceedingsEduardoHernandezNo ratings yet

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- The Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutFrom EverandThe Bridesmaid: The addictive psychological thriller that everyone is talking aboutRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (134)

- His Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsFrom EverandHis Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (100)

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipFrom EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1136)

- Love Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)From EverandLove Life: How to Raise Your Standards, Find Your Person, and Live Happily (No Matter What)Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1462)

- Summary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneFrom EverandSummary of The Art of Seduction by Robert GreeneRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (46)

- The Guilty Wife: A gripping addictive psychological suspense thriller with a twist you won’t see comingFrom EverandThe Guilty Wife: A gripping addictive psychological suspense thriller with a twist you won’t see comingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1149)

- Follow your interests: This will make you feel better about yourself and what you can do.: inspiration and wisdom for achieving a fulfilling life.From EverandFollow your interests: This will make you feel better about yourself and what you can do.: inspiration and wisdom for achieving a fulfilling life.No ratings yet

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Energy Codes: The 7-Step System to Awaken Your Spirit, Heal Your Body, and Live Your Best LifeFrom EverandThe Energy Codes: The 7-Step System to Awaken Your Spirit, Heal Your Body, and Live Your Best LifeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (159)

- The Basics of a Course in MiraclesFrom EverandThe Basics of a Course in MiraclesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (226)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (170)

- Deep Sleep Hypnosis: Guided Meditation For Sleep & HealingFrom EverandDeep Sleep Hypnosis: Guided Meditation For Sleep & HealingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (104)

- Neville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!From EverandNeville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (285)

- Manipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesFrom EverandManipulation: The Ultimate Guide To Influence People with Persuasion, Mind Control and NLP With Highly Effective Manipulation TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1412)

- Summary of The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman by Timothy FerrissFrom EverandSummary of The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-Loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superhuman by Timothy FerrissRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (83)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Peaceful Sleep Hypnosis: Meditate & RelaxFrom EverandPeaceful Sleep Hypnosis: Meditate & RelaxRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (145)

- Summary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietFrom EverandSummary of Mary Claire Haver's The Galveston DietRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)