Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Art of Arch Top Downbeat PDF

Art of Arch Top Downbeat PDF

Uploaded by

Waldeir Benedito SilvaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Art of Arch Top Downbeat PDF

Art of Arch Top Downbeat PDF

Uploaded by

Waldeir Benedito SilvaCopyright:

Available Formats

GUITAR SCHOOL ’S GUIDE TO LEARNING JAZZ

The Art of the

Archtop

Benedetto

18-inch

Cremona

archtop

ALSO INSIDE

78 / Elliott Sharp 80 / Buddy Guy 82 / Toolshed

Master Class Solo Transcription 84 / Gear Box

artof the

The

Archtop

A Classic Design Endures as the

Choice of Jazz Guitarists By Keith Baumann

THE ORIGINS OF THE MODERN GUITAR CAN BE TRACED BACK HUNDREDS,

if not thousands, of years. But for many jazz players, the most important date in the instru-

ment’s long history is 1897, when Orville Gibson introduced the first carved archtop gui-

tar. Since then, the archtop has made an undeniable impact on the evolution of jazz and

popular music. Surviving radical shifts in musical taste and huge technological advance-

ments, this uniquely American innovation has steadily held its own and continues

to maintain a fiercely loyal following among players and luthiers who appreciate its

strong tradition and also understand its continually evolving and limitless potential.

Gibson broke new ground when he applied traditional Italian vio- in a few short years the archtop had completely replaced the tenor banjo as

lin-making techniques to the construction of fretted instruments in order to the jazz musician’s rhythm tool of choice. Gibson and other manufacturers

achieve greater clarity and projection. In the early 1900s, the newly formed continued to refine the archtop by increasing body size for more volume and

Gibson Company produced guitars and mandolins that featured carved tops adding cutaways for higher fret access. Eventually magnetic pickups were

and backs, X-pattern bracing, floating bridges and an oval-shaped sound added to the archtop, allowing it to be featured as a solo instrument. The

hole. In 1922, hoping to boost sagging sales, Gibson hired acoustic engineer unique tone produced by amplifying a fully acoustic guitar endures to this

Lloyd Loar to redesign the company’s offerings. Loar made several key mod- day as the heart and soul of the jazz guitar sound.

ifications to Orville’s original designs, adding violin-style f-holes, parallel Many guitar builders have followed in Gibson and Loar’s footsteps over

bracing bars, elongated fingerboards and tap-tuned carved tops to maximize the last 116 years. Numerous manufacturers and luthiers simply copied the

responsiveness. Although he was with Gibson for a few brief years, Loar’s two original Loar designs, but others took their own paths, creating instruments

instruments, the F5 Master Model mandolin and the L5 Master Model arch- tailored to the needs of the constantly evolving jazz musician. New York’s

top guitar, became part of the fabric of American music—with the F5 man- John D’Angelico and his apprentice Jimmy D’Aquisto were among the most

dolin sculpting the sound of bluegrass music in the hands of Bill Monroe and well-known and respected luthiers who pushed the envelope of modern

the L5 guitar becoming the de facto standard for jazz guitarists worldwide. archtop design, inspiring a whole new generation of builders.

Engineered to cut through the volume of a large orchestra, the L5 was Even though the archtop represents a relatively small niche in today’s

designed as an acoustic rhythm instrument. It was so successful that with- overall guitar market, there is a surprisingly large number of luthiers current-

Frank Vignola

plays a Thorell

FV Studio.

ART

AGG

YT

Monteleone

RA

Radio City

:

TO

O

PH

Wilkie 16-inch

Northern Flyer

PHOT

O : VINCENT RICARDEL

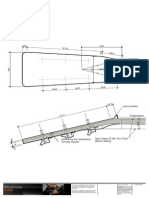

Wyatt Wilkie

works with his

homemade

side-bending

press.

PH

O TO

P

: EM

BOB STAM

ILY

CH ARET

TE

PHOTO:

Bob Benedetto

literally wrote the

book on how to

build an archtop.

Left: carving a

45th anniversary

Benedetto guitar

headstock.

JULY 2013 DOWNBEAT 73

ly devoted to the art of hand-building custom arch- produce treble tones that are sweet and lyrical

top instruments. In addition, several established gui- like a human voice,” he said. Monteleone

tar manufacturers now feature a selection of archtop attributes the endurance of the archtop to

models within their product lines. To gain insight its inherent beauty along with its ability

into the instrument’s subtle nuances and long-last- to function as an acoustic, electric or

ing appeal, we interviewed some of the finest mas- combination of both.

ter archtop builders and a few select factory builders.

Although each luthier strives to place his individual Benedetto

stamp on each guitar, they all share a set of core val- BOB BENEDETTO IS A NAME

ues that define what the archtop guitar is all about. that comes up frequently when

The luthiers we spoke with expressed strong talking with other luthiers—no

feelings of respect for the tradition created by the surprise, since he literally wrote

builders that have preceded them. They are also the book on archtop guitar build-

aware of the significant role that players occupy in ing. Aspiring builders around the

influencing the evolution of archtop design. From world have used his book, Making

the first rough cut of the tonewood to final finish- An Archtop Guitar, to kick-start their

ing and setup, luthiers are absolutely in love with the own careers. Benedetto has been in

process of building a guitar. the business for 45 years and has grown

from a one-man shop into a small man-

Monteleone ufacturer. He is mostly self-taught and has a

JOHN MONTELEONE IS ONE OF THE MOST background in repair as well as violin making. Right

respected builders in the business today. Known from the beginning in 1968, he focused on archtop

for his innovative design work and amazing tone, guitars, citing a strong influence from Gibson and

Monteleone considers his acoustic archtop guitars D’Angelico. Benedetto feels that the strength of the

to be works of “playable art.” Monteleone is primar- archtop lies in its unrivaled sound and unique feel,

ily self-taught but credits much of his experience to and he considers himself a refiner of the guitar, not

his years as an instrument repairman. He began his a re-designer. “It is mostly the maker and not the

building career by making F5 mandolin copies, and wood that makes an instrument,” he said.

after growing tired of cloning Loar’s work, he com- Benedetto wholeheartedly embraces the tradi-

pletely redesigned the F5, resulting in a new model, tional and sees no need to stray too far from

the Grand Artist. Monteleone introduced his first time-honored designs. His refinements are in the

archtop guitar, the Eclipse, in 1978 and has gone on fine details, such as tap-tuning and subtle neck

to create an array of stunning instruments, includ- improvements. “The real challenge is using the

ing his acclaimed Radio City archtop, with its Art same design parameters to create a wonderful-

Deco-influenced architectural motif. ly voiced instrument,” he said. Although the com-

Monteleone is a custom builder and cites pany has expanded into a staff of 10 and produces

D’Angelico as a major influence. “You could really a large selection of models, Benedetto’s involvement

sense the skill and personality in his guitars,” he said. remains mainly with the high-end hand-carved

Monteleone is also a big fan of the original Orville archtops. Benedetto Guitars offers archtops in a vari-

Gibson guitars and utilizes oval-shaped sound ety of styles and price points and does custom one-

ports in several of his models. According off work. The Flagship Series features the carved

to Monteleone, an archtop should models, and the Professional Series includes lami-

have a clear, brilliant tone with a nated and solid chambered bodies.

nice balance and plenty of cut-

ting power that allows you to hear

the wood and not just the strings.

“One of my goals has always been to

Claudio

Pagelli in his

workshop in

Switzerland

Pagelli Res

Knuchel

74 DOWNBEAT JULY 2013

Laplante

17-inch

Sad City

Jean-Pierre

Laplante

archtop in 1980,

he was instant-

ly hooked. Camp-

elleone has an art

Campelleone

Special

background, which he

Series feels has been beneficial to his

guitar building. He offers a

select line of hand-carved

archtops in his Standard,

Deluxe and Special Series.

Campelleone’s premier gui-

tar is his Cameo, and he also

offers a 15-inch design in his

EP Series. His primary goal has

always been to build a traditional

Loar-style archtop, and he said that his attraction

to the guitars stems from the beauty of the instru-

ments, which are like sculptures to him. In terms

of why the archtop has endured for so many years,

Campelleone pointed out that the unique sound of

the amplified acoustic guitar has never been dupli-

cated in a solid body.

Thorell Wilkie

UTAH LUTHIER RYAN THORELL FEELS WYATT WILKIE OF WILKIE STRINGED

rhythm playing and note separation are the heart Instruments summed up his infatuation with arch-

of the archtop guitar, which he considers to be the top building when he said, “I can’t help myself.”

“sound of jazz” and “a living American tradition.” Wilkie started out as a mandolin maker and got

Thorell started building guitars in 1996 and carved his initial exposure to archtops through his associ-

his first archtop in 2005. He is a huge fan of the Lloyd ation with Calton Cases, where he had to examine

Loar archtops and is also influenced by the New and measure instruments for clients ordering cus-

York school of D’Angelico and D’Aquisto. A true tom flight cases. Wilkie was fortunate to appren-

hand-builder, Thorell feels the archtop’s appeal lies in tice with Benedetto and recalled how “that changed

its limitless potential and ability to produce a consis- everything.” He hand-builds two basic models in his

tent tone from the lowest to highest notes. The Sweet E British Columbia workshop: the Northern Flyer and

and FV (Frank Vignola) are some of his better-know the Strathcona. He also does custom orders. “The

models, but Thorell enjoys building custom instru- mystery of acoustic tone is so alluring,” said Wilkie,

ments that can be individually voiced for a particular noting that it’s all about the wood. “Acoustic music

player. Although he maintains a strong respect and in general has endured longer than amplified music,

love for the tradition, Thorell considers his craft to be and it’s about the feel as much as it is the tone.”

a vibrant process that is constantly evolving. He often

experiments with sound port placement and utilizes Marchione

a subtler arch on his guitars’ tops to produce a richer STEPHEN MARCHIONE OF TEXAS GOT HIS

tone, which he feels has become more important than start as a violin maker and has been building guitars

generating sheer volume. full-time since 1990. He gained a deep respect for the

instrument during his college years while playing in

Campelleone big bands and bases most of his designs on the clas-

EAST COAST BUILDER MARK CAMPELLEONE sic archtops of D’Angelico and D’Aquisto. Marchione

started out building electric basses and doing repair pointed out that “the archtop is a transcendent thing

and restoration work. But when he built his first that rises above being a simple instrument.” As a

JULY 2013 DOWNBEAT 75

player himself, he feels that these guitars with the player who relates to the feel thing between an archtop and a

are extremely compelling and deep- and unique acoustic properties of the flat top with lots of warmth and

ly satisfying to hold and play, and that guitar. He offers three models in his a longer note sustain. He puts his

hand carving is the only way to truly Premium line and three models in the personal stamp on his guitars with

voice an instrument. “You really have to Standard line. In addition, Andersen custom cutaway profiles, beautiful

listen to the wood,” he said. Marchione builds a line of Specialty models. comma-shaped f-holes and utiliza-

offers hand-built archtop models that tion of non-standard woods such as

range in size from a 15-inch up to an D’Lorenzo mahogany, rosewood, cedar and wal-

18-inch and even include a 7-string and SCOTT LAWRENCE OF D’LORENZO nut. Two basic models are available Steven

Andersen

baritone design. Guitars in Oklahoma tries to stay directly from D’Lorenzo Guitars: the

“at the intersection tradition of and fully acoustic NCAT (New Concept

Andersen innovation.” Lawrence warmed up Arch Top) and the Blue Flame

SEATTLE’S STEVEN ANDERSEN on a few flat-top guitar kits before Electric Archtop.

has been building guitars since high building his first archtop in 2003.

school. After starting his own shop, His background includes experi- Laplante

Andersen began to focus on build- ence as an instrument repairman as JEAN-PIERRE LAPLANTE IS A

ing F5 mandolins and doing repair well as furniture building and cab- Canadian luthier who wants to push

work. The opportunity to examine inet restoration. Lawrence used the the archtop in new directions. Mainly

and work on a wide variety of clas- Gibson ES-175 as a take-off point for self-taught, he built his first Telecaster-

sic archtop instruments was a signif- his first archtop but utilized a hand- style electric guitar in 1993 but began

icant factor in sparking his building carved top instead of the usual lam- his love affair with the archtop in

career. Andersen built his first archtop inate to increase acoustic responsive- 2003 when he was commissioned to

in the late 1980s and considers him- ness. He also cites Benedetto’s book build a guitar in the L5 style. Laplante

self to be mostly self-taught. “James and CDs as learning tools and draws immediately realized how much more

D’Aquisto was a big inspiration, par- inspiration from D’Aquisto’s inno- rewarding this process was for him

ticularly his innovative cutting-edge vative attempts at improving acous- compared to building solid-body

guitars, which inspired me to create tic tone. Lawrence summed up his electrics. He is highly influenced

Andersen

my own designs,” he said. Regarding attraction to the archtop by saying, “It by Benedetto for the basics but Electric

his personal building style, Andersen is classy, beautiful and graceful even cites Monteleone as a major inspi- Archie

noted, “There is always room for inno- without ornamentation.” As a build- ration for innovation and design:

vation and experimentation.” A true er, he is constantly evolving and tak- “He is so creative and inspired me

artisan who builds each guitar one at ing chances, which he feels is the only to move away from the tradition, and

a time, by hand, Anderson said that he way to innovate. Lawrence shoots for [Monteleone] showed me there is still

senses a deep emotional connection a different tone, searching for some- room to take the guitar somewhere

else,” he said. Laplante enjoys the

challenge of building and hopes

to push the envelope of the arch-

top and expand its audience. His

feeling on the appeal of the guitar

is that each one has its own per-

sonality, and from the player’s per-

spective, it makes you want to play

differently and inspires new ideas and

creativity. He addresses the archtop’s

ongoing evlution with several design

changes, including lighter bracing the finest spruce tonewood is grown.

techniques and redesigned soundhole Pagelli offers several archtop mod-

placement. Laplante produces numer- els, including the Patent, Traditional,

ous archtop models from his one-man Jazzability and Ana Sgler, and also

shop, and he noted that the 16-inch does plenty of custom work.

dual pickup laminate models like the

Springtime and Summertime are the Sadowsky

bread-and-butter of his business. He ROGER SADOWSKY BEGAN HIS

also offers several fully carved models. journey with repair and restoration

work. Realizing that to be a great

Pagelli builder you need to be around the

CLAUDIO PAGELLI, WHO BUILDS great players, he relocated to New

his guitars in Switzerland, also utilized York. Although he considers him-

Benedetto’s book in developing his self self-taught, Sadowsky spent two

craft. He loves the old Epiphones and years as an apprentice to Augustino

Strombergs but goes his own way with LoPrinzi. As a repairman, Sadowsky

designing archtops for open-minded became aware of the problems asso-

players. Several of his models feature a ciated with amplifying an acoustic

radical departure from standard arch- guitar. He also spent 15 years servic-

top designs, and he prides himself on ing jazz legend Jim Hall’s D’Aquisto

improving upon the ergonomics of the archtop. These experiences set him

guitar. Pagelli describes his guitars as on a mission to design and build a

“Swiss precision with an Italian flair.” road-worthy instrument that could

He feels he has an advantage living be easily amplified. Sadowsky worked

close to the Swiss Alps, where some of closely with Hall in developing his

76 DOWNBEAT JULY 2013

first archtop guitar, which, like Hall’s turing Canadian woods and built Korean factory and features the EXL- Mandolin Company. Eastman trans-

D’Aquisto, was a laminate. “I was try- entirely in North America. According 1, EX-SS and EX-SD. lated Benedetto’s videos into Mandarin

ing to build a guitar that Jim would to Godin, value and innovation are to train the company’s craftsmen. “We

be comfortable with,” Sadowsky said. keys to the success of the company’s Ibanez wanted to build guitars with the exact

The resulting guitar was the Jim Hall archtops. He feels that demand for IBANEZ, WHICH STARTED OUT same methods used during the gold-

model, his premier archtop. archtops is high with many musicians by copying classic American guitars en age of archtop design,” said prod-

Sadowsky’s archtops are made in discovering jazz and taking it in new in Japan, began building archtops in uct specialist Mark Herring. Eastman

Japan, where he also manufactures directions. Godin archtops are man- the mid-1970s but really made a mark built its flagship models, the AR805CE

his Metro Line of basses. He does the ufactured using CNC machinery and in 1978 with its first George Benson and AR810CE, in 2001 using tradition-

final fretwork, electronics and setup laser cutters, techniques that play a signature guitar. Ibanez later expand- al hand-carving techniques and estab-

at his shop in New York. Sadowsky’s major role in allowing them to offer ed the line with a Pat Metheny model. lished a new standard in quality from a

main goal is to produce guitars for consistent quality at attractive prices. In distinguishing Ibanez from a cus- Chinese manufacturer. Producing fully

gigging musicians, and all his mod- tom builder, company spokesper- hand-carved guitars out of an Asian

els feature a special laminate top that D’Angelico son Ken Youmans said, “We build factory was a visionary concept and

not only offers resistance to feed- D’ANGELICO GUITARS OWNS THE guitars for a market segment as has allowed Eastman to offer profes-

back but responds well acoustically. exclusive rights to use the name of the opposed to an individual player, and sional-grade instruments at extreme-

He sees a current trend toward small- world-renowned guitar maker (who even though we do production, it is ly affordable prices. “We walk the

er body sizes and shallower depth and passed away in 1964). Initially offer- still an art form to us.” While arch- fine line between manufacturing and

reflects this in many of his guitars. ing only inexpensive import copies of tops are not huge sellers for Ibanez, hand-crafting,” Herring explained.

Affordability is also a top priority for the legendary archtops, D’Angelico the guitars are a point of pride that’s Eastman now offers a selection of all

Sadowsky. In addition to the Jim Hall, Guitars has recently undergone sig- critical to the company’s reputation. solid-wood, hand-built archtops and

Sadowsky Guitars now offers a wide nificant changes, revamping its Ibanez currently offers three lines of recently added a laminate model.

range of archtop models, including the import line and introducing a new laminate guitars in its archtop series.

Jimmy Bruno, the LS-17 and SS-15,

plus a semi-hollow model.

USA Masterbuilt Guitar, which is

an entirely hand-crafted clone of a

1943 Excel. According to Sales V.P.

Manufactured in China, the Artcore

is the most affordable line, followed

by the Artstar Series. The Japanese-

M ore than a century after its

introduction, the archtop gui-

tar is still very much alive and well.

Godin Adam Aronson, D’Angelico Guitars made Signature Series represents Although it is always evolving, it

GODIN GUITARS WAS A WELL-ES- used the original blueprints and an Ibanez’s high-end offerings. never loses sight of its roots. While it

tablished company before it released MRI machine to reproduce an Excel continues to attract and inspire new

its first archtop guitar. Robert Godin, as closely as possible. “D’Angelico Eastman fans, it never leaves behind its loyal

a jazz player, felt there was a lack of was a major player and was known HAVING PRODUCED A FULL LINE devotees. Its magic can be found as

decent affordable guitars, so he decid- for quality,” Aronso said. “We want of orchestra instruments for years, much in the skilled hands of its ded-

ed to fill the void with the 5th Avenue, to live up to the name.” D’Angelico’s archtop guitars were a logical next icated builders as in the artistry of its

an all-acoustic laminate archtop fea- standard line is manufactured in its step for the Eastman Guitar and great players. DB

JULY 2013 DOWNBEAT 77

GUITAR SCHOOL Woodshed MASTER CLASS

BY ELLIOTT SHARP

Algorithms, Self-Organizing Systems and

Other Forms of Extra-Musical Inspiration

TWO MUSICIANS PLAY TOGETHER WITHOUT DISCUSSION OR SyndaKit 01

pre-planning. One initiates with a short repetitive motif, tonal and regular. The

other responds with a jagged slash that is followed by the first, echoing the slash

then returning to the repetitive motif. The second repeats a fragment of the ini-

tial motif and adds a descending scalar riff in the original tonality. As they con-

tinue, they follow a protocol that has been subconsciously established, expanding

and elaborating upon it. The musicians have created an internalized instruction

set to structure their play, a common occurrence in free improvisation practice.

Though the internal details may vary, the structure will continue to evolve

from the first gestures while refer-

Elliott Sharp ring back to them. After the fact,

this musical interaction may be

scored out or codified, to be repeat-

ed or further refined. In this exam-

ple, one sees the generation of a

simple algorithm, a more techni-

cal term for an instruction set. An

instruction set may be extremely

detailed and spell out every action

and permutation, or it may be more Hudson River Nr. 2

open and conceptual.

In an improvising situation,

there is nothing to prevent new ges-

tures from being introduced or a

divergent path to be taken at any

time. This might have the effect of

injecting excitement into a predict-

SASCHA RHEKER

able structure but could possibly

derail a developing narrative. From

attempting to balance these oppo-

site poles, musicians have long desired to focus on unscripted music-making to

give them the sense of inevitability inherent in a well-composed piece of music

but at the same time retaining the edge-of-a-cliff thrill of an improvisation. I’ll

describe a few of the approaches I’ve made use of.

While attending Cornell University between 1969–1971, I played in psyche-

delic rock bands replete with extended jamming and referencing Jimi Hendrix,

the Grateful Dead, Captain Beefheart and Miles Davis. Later at Bard College,

Roswell Rudd welcomed us into the mysteries of Thelonious Monk, Duke

Ellington, heterophony and free improvisation. By the summer of 1973, I was

living on the Hudson River in upstate New York and hammering out notation In 1974, I moved to Buffalo to study with Lejaren Hiller, Morton Feldman

but finding greater pleasure in making graphic scores and improvising. My play- and Charles Keil. Hiller was a pioneer of computer music whose Illiac Suite of

ing on guitars and reeds at this time was as much influenced by the flow of the 1956 (co-composed by Leonard Isaacson) was a set of algorithms rather than

nearby river and its tides; the sound and sights of the birds and insects; sunrise, written music. These algorithms gave the computer instructions, rules for writ-

sunset and stars; storms, calm and all weather in-between. To formalize these ing harmony and melody, with which it would compose music. Hiller often

approaches, I began to develop a list of simple instruction sets, my Hudson River spoke of the “metamusic” underneath what we hear—the processes that give rise

Compositions, to be used as a score for myself or other improvising musicians: to a structure and the sounds and interactions that populate it. Hiller inspired me

Play as fast as possible in rhythmic unison while varying pitches and sounds. to think of each piece of music as an organism whose identity was clearly defined,

Branching: follow the tangential but maintain the initial impulse. although its development and growth could take it through many forms. While

Emulate the river: never play the same thing twice but maintain a single identity. in Buffalo, I used the simple algorithms of my Hudson River Compositions to cre-

Chop space into fragments; combine fragments to form a space. ate pieces and form the basis of improvisations with fellow musicians.

Maximize density. A longtime obsession of mine since grade school had been the Fibonacci

Never play at the same time as another player but build a groove. series of numbers, which is formed by summing two numbers to generate the

Slow a line to half-speed and repeat the process, again, again. next. Starting with (0, 1) the series yields: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89 ... . I

Overtones—map speed to range. used Fibonacci numbers in my 1981 opera Innosense to create an overall archi-

Hemiola: each player choose a different time signature and repeat a simple fig- tecture of proportional sections and in the 1982 orchestral piece “Crowds And

ure in that time. Power” to generate rhythms and structure. In 1984, I found that the ratios of

Play the opposite. adjacent Fibonacci numbers could be used to generate a tuning for my guitar.

Play what you see with your eyes open; play what you see with your eyes closed. The ratio of 2/1 is an octave, 3/2 a perfect fifth, 5/3 a Just-Intoned major sixth

78 DOWNBEAT JULY 2013

Foliage 26A

and 8/5 a Just-Intoned minor sixth. The resultant tuning was clear and ringing

yet ambiguous in tonality. The sound invited exploration, and combining the

overtones in various locations on the neck with Fibonacci-based rhythms and

structures set me on the path of composing the music for the first album by my

band Carbon and my first string quartet, Tessalation Row.

The fascinating study of bird flocking and its relationship to African drum

choirs, hunting packs and RNA duplication led me to compose SyndaKit in 1998.

SyndaKit sets out to create an organism that lives to groove, to form large unisons

and to mutate. Intended for 12 musicians, SyndaKit uses 144 composed frag-

ments called Cores and an instruction set. The musicians may make loops from

their own Cores, chain their Cores with those of other musicians, “pop out” with

short improvised gestures that may then be looped and introduced into the sys-

tem, and attempt to build long unisons. There is no correct or incorrect version of

SyndaKit. In fact, using the algorithms or instruction set, players could perform

SyndaKit without ever using any of the composed Cores and it would still sound

like SyndaKit! It has been performed and/or recorded by my own Orchestra

Carbon, Zeitkratzer ensemble in Berlin, the Beijing New Music Ensemble and

various ad hoc groups of 12 guitarists, keyboards, percussionists or string players.

In the last 10 years, I’ve gone back to generating graphic scores. While I con-

tinue to create detailed, fully notated scores for string quartet and orchestras, at

the same time I welcome the input of players who can use their improvisation-

al skills to interpret music that may be more conceptual or abstract. After using

electronics for decades to process the sound of instruments, I find greater plea-

sure and more tactility and presence in the sound of unamplified acoustic instru-

ments. There are myriad extended techniques in use to help create unheard and

exotic sounds, and the current generation of players has them at their fingertips.

To help elicit these sounds, my strategy is to export my pages of composed nota-

tion from Sibelius into graphic editing applications such as Photoshop, GIMP

and Graphic Converter. Using plug-ins, I can filter, modulate, chop, multiply,

augment, stretch and invert, much in the same way that I used these processes

with live or recorded sound. With disciplined and attentive players, these scores

can generate unique manifestations. Current pieces making use of this approach

include Foliage, Volapuk, Seize Seas Seeths Seen and Venus & Jupiter. DB

Elliott Sharp is an American multi-instrumentalist, composer and bandleader. A central figure in

New York’s avant-garde and experimental music scenes for more than 30 years, he has released

over 85 recordings ranging from orchestral music to blues, jazz, noise, no wave rock and techno.

Sharp has composed scores for feature films and documentaries; created sound design for

interstitials on The Sundance Channel, MTV and Bravo networks; and has presented numerous

sound installations in art galleries and museums. Visit Sharp online at elliottsharp.com.

JULY 2013 DOWNBEAT 79

GUITAR SCHOOL Woodshed SOLO

BY JIMI DURSO

Buddy Guy’s Classic Guitar Solos

on ‘Mary Had A Little Lamb’

Buddy

Guy

STILL PLAYING WITH INCREDIBLE ENERGY measures 27–28, where he plays the A major

at age 76, Buddy Guy has been an influence on mul- pentatonic scale. This would be an unusu-

tiple generations of guitarists. His songs have been al choice in E, except when you consider that he

covered by many blues and rock icons, including plays this scale over the IV chord, which is A major.

“Mary Had A Little Lamb,” from 1968’s A Man And Even when it goes back to the E chord, Guy keeps the

The Blues (Vanguard), which Stevie Ray Vaughan F# and C# from the A major pentatonic, giving the

covered on his first release. It’s a classic track, and next two measures a dorian flavor.

both the middle solo and the solo on the fadeout Guy’s phrasing is a crucial part of this improvi-

from Guy’s original are transcribed here. sation. For the most part, Guy’s solos on this track

The song is based on a simple eight-bar form mirror his singing: starting on a weak measure and

starting on the IV chord and then proceeding to I, resolving to a strong measure (as in bars 1–2, 3–4,

V and I, each chord getting two measures. Though 5–6, 11–12, 15–16, 18–19, 20–21, 22–23, 24–25, 26–27

it’s in E major, most of Guy’s playing comes out of and 28–29). The only deviations from this phrasing

the E minor pentatonic scale, which when played are when he starts out on the weak bar (measures

over a major chord progression gives us what many 7–9) but continues through the strong measure to

would say is an essential sound of the blues (this is resolve on the next weak one (bars 13 and 14), where

also why the transcription is presented in E minor, he plays short one-measure ideas rather than cross- “two” (12, 13, 21, 29), the “and of three” (25, 27) and

rather than major). Note, however, that Guy has a ing the bar line. On the fadeout, Guy starts a long even once on the “e of one” (16).

tendency to bend his G naturals a bit sharp, mak- phrase that covers four measures, possibly more as But in general, Guy starts his lines at the begin-

ing them a bit less minor sounding. He also often we can’t hear where he goes after the fade. ning of a weak measure and concludes them toward

bends his A into a B !; adding this flat fifth produces The phrasing adds a consistency to his solos, and the beginning of the following strong measure,

the sound commonly referred to as the blues scale. also connects them to the vocal line. He adds more which is exactly what the lyrics do. In this manner he

Guy only starts to deviate from this sound in consistency by starting most of his phrases on the produces a pair of solos that develop from the song

“and of one” (bars 3, 5, 7, 11, 15, 18, 22, 24, 26 and itself and evoke the same mood. DB

28). But so as not to get predictable, Guy varies where

he ends his phrases. We hear him conclude on the Jimi Durso is a guitarist and bassist based in the New York

downbeat (4, 19), the “and of one” (2, 6, 9, 23), the area. Visit him online at jimidurso.com.

Middle Solo

Fadeout Solo

80 DOWNBEAT JULY 2013

GUITAR SCHOOL Toolshed

Ibanez Pat Metheny PM200 & PM2

Old Friends, New Archtops

T

he relationship between Ibanez and guitarist Pat Metheny more apparent.

dates back to the late 1970s, when the company first There is no doubt that the PM200 is the superior guitar in terms of

approached the young artist at a concert in Japan. its playability and tone. Available for a street price of about $3,499, the

The resulting partnership has produced numerous Metheny PM 200 uses a Silent 58 pickup, a Gotoh floating bridge and a solid

Signature models over the years, and Ibanez recently overhauled ebony PM tailpiece. It has a body depth of 4 ¼ inches, compared to the

those offerings with the introduction of two new Metheny arch- shallower 3 ⅝ inches of the PM2, and also a wider bout of 16 ½ inches,

top guitars: the PM200 and PM2. compared to the narrower 15 ¾ inches of the PM200 model. The neck

The two new Pat Metheny Signature guitars share many profile is slimmer on the PM200, and I found it much

of the same aesthetics and design aspects as more comfortable to play then the slightly chunki-

their predecessors but are targeted at very dif- er PM2 neck. The cutaway is deeper as well, allow-

ferent customers. The Japanese-built PM200 ing easier access to the higher frets. The tone is fat,

is the high-end option, with a list price of warm and smooth, and a nice bite becomes avail-

$4,666. The PM2 is the first Signature gui- able when you open up the tone pot.

tar to be included in Ibanez’s Chinese- The PM2 is solid jazz guitar, considering its

manufactured Artstar line and represents the attractive $999 street price. The Super 58 pick-

affordable alternative with a list of $1,333. up performs well but is definitely not as smooth

The new Pat Metheny Signature or clean as the Silent 58 on the PM200. The PM2

models feature a single cutaway features an Art-1 floating bridge, a KT30 wire tra-

design with maple top, back and peze tailpiece and, like the PM200, it also features

sides and a single neck-mounted gold-plated hardware throughout. Overall playabil-

humbucker pickup. Both instru- ity definitely exceeded my expectations for a guitar

ments feature a set-in 22-fret neck in this price range.

with a 24 ¾-inch scale length. The Ibanez has done a nice job in re-engineering its

inlay patterns on the ebony fin- Pat Metheny Signature models. Both the PM200

gerboard and headstock are vir- and PM2 are quality instruments and offer a good

tually identical as well. However, set of options for both the serious pro and the aspir-

when playing the guitars side by side, ing amateur jazz guitarist. —Keith Baumann

their differences become considerably ibanez.com

Sadowsky SS-15 Archtop

Fat Sound, Thin Package

F

eaturing a fully hollow body packed into a sleek thinline ume and tone knobs control the single custom-wound

profile, the SS-15 from Sadowsky Guitars bridges the PAF-style pickup mounted at the neck position.

gap between traditional full-bodied archtops and I was struck by how lightweight the SS-15 is.

semi-hollow instruments. Playing unamplified, there is a surprising amount

The inspiration for the SS-15 grew out of requests from of acoustic resonance, with the body vibrating in

customers who loved the Sadowsky Semi-Hollow guitar but response to each note. The 14-fret neck is extremely

wanted an acoustic version for playing jazz. Using the Semi- comfortable, and the wider string spacing makes the

Hollow as a template, Sadowsky created a guitar that shared guitar great for finger-style playing.

its same basic dimensions but did not utilize a center block The SS-15 features the True Tone saddle, which

within the body chamber. Instead, the SS-15 uses traditional is a fully intonated ebony bridge top developed

tone bar bracing, leaving the guitar completely hollow inside by Sadowsky that allows for better intonation

and resulting in a greatly enhanced acoustic response. compared to a standard archtop bridge. The

Luthier Roger Sadowsky said he was looking to create a SS-15 ships with two True Tone bridges:

guitar that is easier to travel with but still maintains the tra- one compensated for a wound G string

ditional archtop tone and feel. In addition, the instrument and a second for an unwound G. The

needed to perform well in amplified situations. The SS-15’s amplified tone of the SS-15 is simply gor-

14 ¾-inch body is actually ⅛ inch deeper than the Semi- geous, reminiscent of a classic archtop.

Hollow and features a slightly wider 1 ¾-inch neck profile. Delivering true archtop tone in a

Like Sadowsky’s archtop guitars, the SS-15 is constructed thinline body makes the SS-15 unique,

from five-ply maple laminate. The appointments are straight- and at $4,175 it will definitely carve out its

forward and traditional, with a solid ebony tailpiece and own niche in the market. —Keith Baumann

matching abbreviated floating ebony pickguard. Basic vol- sadowsky.com

82 DOWNBEAT JULY 2013

You might also like

- Luthieria - Selmer Maccaferri NeckDocument9 pagesLuthieria - Selmer Maccaferri Neckmandolinero67% (9)

- Archtop Guitar PlansDocument1 pageArchtop Guitar PlansBart Stratton83% (6)

- Digital Booklet - Falsettos (2016 Broadway Revival Cast)Document18 pagesDigital Booklet - Falsettos (2016 Broadway Revival Cast)Austin Yang100% (8)

- ManZer GuitarsDocument18 pagesManZer Guitarsdedalus777100% (5)

- Voicing The Steel String Guitar by Dana BourgeoisDocument12 pagesVoicing The Steel String Guitar by Dana Bourgeoisandrea_albrile100% (1)

- The Stratocaster Guitar Book: A Complete History of Fender Stratocaster GuitarsFrom EverandThe Stratocaster Guitar Book: A Complete History of Fender Stratocaster GuitarsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Construction Notes For A Steel String Guitar - SampleDocument32 pagesConstruction Notes For A Steel String Guitar - SampleDennistoun75% (4)

- Make Your Own Electric Guitar & BassDocument95 pagesMake Your Own Electric Guitar & Bassdojcin100% (4)

- Soundboards DF PDFDocument17 pagesSoundboards DF PDFalberto reyes100% (2)

- Acoustic Guitar MakingDocument1,000 pagesAcoustic Guitar MakingRicardo Luis Martin Sant'Anna100% (10)

- The Electric Guitar Sourcebook: How to Find the Sounds You LikeFrom EverandThe Electric Guitar Sourcebook: How to Find the Sounds You LikeNo ratings yet

- Antonio de Torres Guitar Maker His Life and WorkDocument5 pagesAntonio de Torres Guitar Maker His Life and Workclazzyo50% (2)

- 16 Archtop Guitar BuildDocument123 pages16 Archtop Guitar Buildluis7oliveira_2100% (4)

- Master Class Guitar MakingDocument50 pagesMaster Class Guitar MakingCharles Alfaro83% (18)

- Classic 2 TemplatesDocument1 pageClassic 2 TemplatesDaniel Garfo100% (3)

- Progetto TorresDocument1 pageProgetto TorresMichele Pacilli50% (2)

- Intervallic Tunings for Twelve-String GuitarFrom EverandIntervallic Tunings for Twelve-String GuitarRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Guitar PacketDocument22 pagesGuitar PacketSimon Lawrenson100% (1)

- West Side: Center For THEDocument18 pagesWest Side: Center For THEjcruizjr5122No ratings yet

- Make Your Own Spanish Guitar (1957)Document40 pagesMake Your Own Spanish Guitar (1957)Erdem Kapan100% (2)

- The Art and Craft of Making Classical GuitarsFrom EverandThe Art and Craft of Making Classical GuitarsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Archtop Guitar ManualDocument123 pagesArchtop Guitar ManualCarlo351100% (13)

- ItishDocument140 pagesItishGabriel Cano100% (6)

- Grounding An Archtop Tailpiece enDocument11 pagesGrounding An Archtop Tailpiece envvvvv12345No ratings yet

- Bolt On Acoustic Guitar NeckDocument1 pageBolt On Acoustic Guitar NeckJayMorgan50% (2)

- Archtop Build Journal - Fifth Edition - (Low Res)Document122 pagesArchtop Build Journal - Fifth Edition - (Low Res)Jose Maria Hidalgo100% (1)

- Bending Iron For Guitar MakingDocument1 pageBending Iron For Guitar Makingpeter100% (1)

- Guitar Making Guide - Jon SevyDocument170 pagesGuitar Making Guide - Jon Sevyaboutsoundcraft100% (6)

- The Acoustics of The Steel String GuitarDocument418 pagesThe Acoustics of The Steel String Guitaraboutsoundcraft100% (3)

- Instructions Neck AngleDocument21 pagesInstructions Neck Angleandua40100% (2)

- Voicing The GuitarDocument24 pagesVoicing The GuitarHoàng Ngọc-TuấnNo ratings yet

- Martin V Joint NeckDocument1 pageMartin V Joint Neckandua40100% (2)

- Guitar Assembly Work Board - Top View 1937 Hauser Classical Guitar ShapeDocument1 pageGuitar Assembly Work Board - Top View 1937 Hauser Classical Guitar ShapeDaniel Garfo100% (1)

- GuitarBuildingJigsTools v1.1Document16 pagesGuitarBuildingJigsTools v1.1Mochamad Rizal Jauhari86% (7)

- Guitars Design Production and RepairDocument161 pagesGuitars Design Production and RepairPelon1100% (2)

- Archtop Build Journal - Third Edition - Lo Res PDFDocument102 pagesArchtop Build Journal - Third Edition - Lo Res PDFOscar Camacho RosalesNo ratings yet

- Pickup Guitar TechnicDocument59 pagesPickup Guitar TechnicDeaferrant100% (1)

- Double Top BuildingDocument18 pagesDouble Top BuildingaboutsoundcraftNo ratings yet

- Sadowsky Jim HallDocument3 pagesSadowsky Jim HallBetoguitar777No ratings yet

- Tonewood Technical DataDocument24 pagesTonewood Technical DataCaps Lock100% (4)

- Guitar - Luthier - Fender Telecaster Deluxe Plans (1973)Document16 pagesGuitar - Luthier - Fender Telecaster Deluxe Plans (1973)nachof163% (8)

- Acoustic Guitars: Woods and ShapesDocument11 pagesAcoustic Guitars: Woods and ShapesLucas Man80% (5)

- Nov17 PG Ebook DIYGuitarMakeover Vol1 PDFDocument58 pagesNov17 PG Ebook DIYGuitarMakeover Vol1 PDFwhirly1100% (2)

- Acoustical StudyDocument21 pagesAcoustical StudyJim SaligNo ratings yet

- Curso Luthier by Johnny GuitarDocument95 pagesCurso Luthier by Johnny GuitaradmlewisNo ratings yet

- Guitar Shapes Navigator: Measuring the shapes of the guitar and the positions of its elementsFrom EverandGuitar Shapes Navigator: Measuring the shapes of the guitar and the positions of its elementsNo ratings yet

- Tone Wizards: Interviews With Top Guitarists and Gear Gurus On the Quest for the Ultimate SoundFrom EverandTone Wizards: Interviews With Top Guitarists and Gear Gurus On the Quest for the Ultimate SoundRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Guitar HistoryDocument3 pagesGuitar HistoryD01ASSASSINNo ratings yet

- Play Acoustic: The Complete Guide to Mastering Acoustic Guitar StylesFrom EverandPlay Acoustic: The Complete Guide to Mastering Acoustic Guitar StylesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Yr 6 E.O.T 3 Eng Paper - 01 - InsDocument3 pagesYr 6 E.O.T 3 Eng Paper - 01 - InsTracey EssieNo ratings yet

- Guitar Collection: Ken HendricksDocument50 pagesGuitar Collection: Ken HendricksKen Hendricks0% (1)

- The Story of G&LDocument5 pagesThe Story of G&LJoeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 10 - The Sound World of The Early 19 Century Guitar: A Timbral ContextDocument25 pagesChapter 10 - The Sound World of The Early 19 Century Guitar: A Timbral ContextErduandNo ratings yet

- 365 Guitars, Amps & Effects You Must Play: The Most Sublime, Bizarre and Outrageous Gear EverFrom Everand365 Guitars, Amps & Effects You Must Play: The Most Sublime, Bizarre and Outrageous Gear EverNo ratings yet

- HeifetxDocument172 pagesHeifetxTreasuresof VegaNo ratings yet

- For Private Circulation Not For SaleDocument52 pagesFor Private Circulation Not For SalerasihaviniNo ratings yet

- The SeagullDocument26 pagesThe Seagulleatdirt1No ratings yet

- Drama in The Twentieth CenturyDocument17 pagesDrama in The Twentieth Centuryنجلاء مقداد سعيدNo ratings yet

- Garden of The CursedDocument20 pagesGarden of The CursedMacmillan KidsNo ratings yet

- Bennett Cerfs Best Jokes by Cerf BennettDocument100 pagesBennett Cerfs Best Jokes by Cerf Bennettidum brotherNo ratings yet

- History of Roman TheaterDocument24 pagesHistory of Roman TheatermurniNo ratings yet

- SettingDocument9 pagesSettingRaffyNo ratings yet

- KoreaDocument99 pagesKoreaLen-Len CobsilenNo ratings yet

- RoadtoComedy PDFDocument216 pagesRoadtoComedy PDFДрумски ратник100% (1)

- Grammar WorksheetsDocument9 pagesGrammar WorksheetsKamal MulihNo ratings yet

- Porgy and Bess History PDFDocument26 pagesPorgy and Bess History PDFMariana Benassi100% (1)

- Doherty, Pre-Code HollywoodDocument11 pagesDoherty, Pre-Code Hollywoodack67194771No ratings yet

- Cinema VocabularyDocument4 pagesCinema VocabularyКатя НеделяNo ratings yet

- Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound: Diegetic and Non-Diegetic SoundDocument3 pagesSound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound Sound: Diegetic and Non-Diegetic SoundRFrearsonNo ratings yet

- Liverpool Center City Map (May 2015)Document2 pagesLiverpool Center City Map (May 2015)Buen VecinoNo ratings yet

- Napoleonic DBA RulesDocument3 pagesNapoleonic DBA RulesSpanishfuryNo ratings yet

- Fifth Army History - Part IV - Cassino and AnzioDocument318 pagesFifth Army History - Part IV - Cassino and AnziojohnwolfeNo ratings yet

- The Handy Guide For Foreigners in TaiwanDocument110 pagesThe Handy Guide For Foreigners in TaiwanNSENGIYUMVALADISLASNo ratings yet

- Akira Nguyen Ly November 30, 2017Document3 pagesAkira Nguyen Ly November 30, 2017Eva Nguyen LyNo ratings yet

- Tea For Two PianoDocument3 pagesTea For Two PianoyahinnNo ratings yet

- "A Short History of The Euphonium in AmericaDocument15 pages"A Short History of The Euphonium in AmericaRenato SantanaNo ratings yet

- Hollywood Reloaded PDFDocument16 pagesHollywood Reloaded PDFΚώσταςΣταματόπουλοςNo ratings yet

- Enemy ProgramDocument36 pagesEnemy ProgramSouren KhedeshianNo ratings yet

- 09 - The Stella Adler Actors Approach To The Zoo Story PDFDocument32 pages09 - The Stella Adler Actors Approach To The Zoo Story PDFasslii_83No ratings yet

- MIT SM GuideDocument83 pagesMIT SM GuideEdward CallowNo ratings yet

- LGBT+ Community in The of Polytechnic University of The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesLGBT+ Community in The of Polytechnic University of The PhilippinesJed BonbonNo ratings yet

- The Merciad, April 13, 1984Document8 pagesThe Merciad, April 13, 1984TheMerciadNo ratings yet