0% found this document useful (0 votes)

200 views8 pagesBenefits of Extensive Reading in ESL

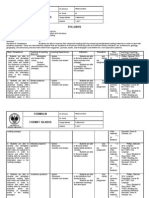

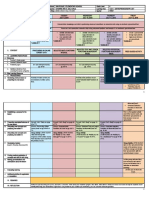

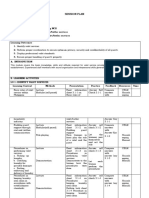

The document discusses establishing an extensive reading program for elementary level English learners in Yemen. It provides research evidence that extensive reading programs benefit language learning by providing comprehensible input, enhancing general language competence, increasing exposure to the language, improving vocabulary and writing skills, motivating learners, consolidating previously learned language, building confidence with longer texts, encouraging exploitation of textual redundancy, and facilitating development of prediction skills. Practical advice is given on running extensive reading programs, including maximizing learner involvement, providing guidance, and encouraging reading at home.

Uploaded by

Ha AutumnCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

200 views8 pagesBenefits of Extensive Reading in ESL

The document discusses establishing an extensive reading program for elementary level English learners in Yemen. It provides research evidence that extensive reading programs benefit language learning by providing comprehensible input, enhancing general language competence, increasing exposure to the language, improving vocabulary and writing skills, motivating learners, consolidating previously learned language, building confidence with longer texts, encouraging exploitation of textual redundancy, and facilitating development of prediction skills. Practical advice is given on running extensive reading programs, including maximizing learner involvement, providing guidance, and encouraging reading at home.

Uploaded by

Ha AutumnCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd