Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BMC Medical Education

Uploaded by

Yanny Labok0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views12 pagesOriginal Title

1472-6920-4-16.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

11 views12 pagesBMC Medical Education

Uploaded by

Yanny LabokCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 12

BMC Medical Education

Research article Open Access Perceptions of first and third

year medical students on self-study and reporting processes

of problem-based learning Berna Musal†, Yucel Gursel*†, H

Cahit Taskiran†, Sema Ozan† and Arif Tuna

Address: Medical Education Department, Dokuz Eylul School of Medicine, Inciralti, Izmir, Turkey

Email: Berna Musal - berna.musal@deu.edu.tr; Yucel Gursel* - yucel.gursel@deu.edu.tr; H Cahit Taskiran -

cahit.taskir@deu.edu.tr; Sema Ozan - sema.ozan@deu.edu.tr; Arif Tuna - ariftuna@hotmail.com * Corresponding author †Equal

contributors

Published: 22 September 2004

BMC Medical Education 2004, 4:16 doi:10.1186/1472-6920-4-16

Abstract Background: The objective of this study is to investigate the perceptions of first and third year

medical students on self-study and reporting processes of Problem-based Learning (PBL) sessions and

their usage of learning resources.

Methods: The questionnaire applied to the students consisted of; questions about students' perceptions

on searching and preparing phases of the self-study process, the breadth and depth of discussion during

reporting phase and the usage of learning resources.

Results: First-year students spent more time for self-study and more highly rated the depth of discussion

compared to third-year students. The searching and preparing phases of the self-study process were

considered as statistically important factors strongly influencing the breadth and depth of discussion

during the reporting phase. The effect of extensiveness of searching on the depth of discussion was

negative among the first-year students, and positive among third-year students.

Conclusions: The relative shortness of third-year students' self-study periods can be related to their

mental weariness, decreased motivation or first-year students' slowness in accessing appropriate

resources. The third-year students' more frequent use of textbooks may be due to the improvement of

their abilities in reaching relevant learning resources. The findings implied that the increase in students'

PBL experience paralleled the development of their discussion skills using different learning resources.

Background The institution of the present study, Dokuz Eylul Univer- sity School of Medicine (DEUSM), has been

implement- ing Problem-based Learning (PBL) in its undergraduate curriculum since the 1997–1998 academic year.

The dura- tion of undergraduate medical education is six years. PBL is the principal educational strategy in the first

three years. Task-based learning strategy was adopted as an educa-

Received: 20 May 2004 Accepted: 22 September 2004

This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16

© 2004 Musal et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use,

distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

tional strategy for clerkships in the 2000–2001 academic year. During the first three years of undergraduate educa-

tion, PBL sessions are the main focus of a modular structure.

The three objectives of PBL are; acquisition of essential knowledge, use of knowledge in clinical contexts and self-

directed learning [1]. In a PBL programme, the students

Page 1 of 7 (page number not for citation purposes)

BioMed Central

BMC Medical Education 2004, 4:16 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16

use a seven-step procedure to structure their activities. This procedure consists of clarifying vague phrases and

concepts in the problem, defining the problem, analysing the problem on the basis of prior knowledge, arranging the

proposed explanations, formulating learning objec- tives, trying to fill in the knowledge gaps by means of self study

and reporting the findings in the group [2]. Individ- ual study is an essential step of information processing approach

to learning. The group members individually collect information with respect to the objectives [3].

PBL curriculum emphasises the development of self-regu- lating skills. Rather than being passive recipients of

infor- mation, students are expected to be actively involved [4]. The diversification of learning resources and their

access routes had a considerable impact on professional skills development. Due to the fact that medicine requires

life- long learning, it has become important for students to dis- cover learning resources on their own and to interpret

their findings. The use of a variety of resources necessitates the processing of information through critical self-

directed inquiry. Important components of a PBL curricu- lum are self-directed learning and students' investigation

of learning objectives. They support deep approaches to learning. Compared to traditional lecture-based curricu-

lum, students in a PBL curriculum use a greater number and variety of resources [5].

In PBL, students are encouraged to take substantial responsibility for their learning. Small group discussions

stimulate independent and active learning. They guide the students during their independent and self-directed learn-

ing. During a PBL group session, limited only by the boundaries of their prior knowledge, students try to clarify the

issues being discussed. The issues that cannot be explained thoroughly are formulated as student-generated learning

objectives which will guide the students during their independent and self-directed learning.

During the searching phase of individual study, students are expected to refer to different learning resources and

search for literature relevant to their learning issues. The findings are evaluated and prepared for the group discus-

sion. The extensiveness of different learning resources used is an indicator of students' self-directed learning skill.

The consultation of diverse information sources influences the breadth and depth of discussion of the tutorial group

during the reporting phase [6].

The iteration of self-directed learning periods leads the students to organise and review the learning resources crit-

ically. Through this critical approach, a major educational objective of PBL, the learning resources can be efficiently

and effectively accessed and relevant information can be elaborated to form the theoretical basis leading to the

Page 2 of 7 (page number not for citation purposes) solution of the problem [1]. Students learn most effec- tively

when using a variety of information resources. Therefore, the provision of adequate resources meeting the needs of

different learning styles is important. Stu- dents' accessibility to these learning resources may be lim- ited if they are

preserved at different locations under the management of different departments [7]. Since the beginning of the

curriculum change process in Dokuz Eylul University School of Medicine (DEUSM), a special emphasis has been

given to the diversification and improvement of learning resources, and facilities have been improved to meet the

learning needs of PBL stu- dents. During the first three academic years of DEUSM, approximately 30–35% of the

weekly schedule is allo- cated to students' self-study periods. Several types of learning resources such as the library,

the Learning Resources Centre and a computer laboratory with Internet access are available to students. In addition,

the staff teachers provide appointment-based scientific counsel- ling upon request. The library, offering a wide

variety of printed material like textbooks and periodicals is open on office days and weekends between 8:30

a.m.–11:00 p.m. The Learning Resources Centre, an interactive learning environment inaugurated in the 2001–2002

academic year, is open on office days between 8:30 a.m.–7:00 p.m. The learning resources of the centre are;

CD-ROMs, video- tapes, microscopes, histology and pathology slides, mod- els & mannequins, posters and

computers with Internet access. The centre's exhibitions of learning material are synchronous with the PBL modules

being implemented.

During the first week of their medical education, first-year students attend a PBL orientation course. This course

con- sists of basic principles of PBL, student and tutor roles and presentation of available learning resources in

DEUSM. All tutors are initially required to take a PBL course and regularly attend weekly tutor meetings [8]. The

tutor pro- file of the first three years is similar. Faculty members from all existing preclinical and clinical

departments fulfil tutor role in PBL groups for determined periods of time during an academic year. Some

alterations observed by tutors in preparing and reporting processes between nov- ice and experienced PBL students

led us to plan the present study.

The research questions of this study are;

√ What were the differences between first and third-year students' perceptions with respect to self-study and report-

ing processes of PBL?

√ What were the length of students' self-study times and their usage of learning resources?

BMC Medical Education 2004, 4:16 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16

√ What was the overall and year-specific impact of self- study process on the breadth and depth of discussion dur-

ing the reporting phase?

The objective of the present study is to investigate and compare the perceptions of first and third-year PBL stu-

dents on self-study and reporting processes and their usage of learning resources.

Methods The first-year students of DEUSM who were recently intro- duced to PBL programme and completed their

first semes- ter and the third-year students who had a two and a half year experience in the PBL programme were

included in this study.

The questionnaire consisted of questions about students' perceptions on searching and preparing phases of the self-

study process, the breadth and depth of discussion during reporting phase and the usage of learning resources. The

questionnaire implemented and tested for validity and reliability in Maastricht University [6] was translated into

Turkish, using expressions appropriate for our study group. Two questions, one on self-study time and the other on

the usage of learning resources were added (Appendix 1).

The participants reflected their perceptions of 22 ques- tionnaire items, grouped under the headings of searching and

preparing phases of self-study process, breadth and depth of discussion during the reporting phase, on a five- point

scale ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree. The points attributed to the items of the scale were

evaluated between 1 to 5 points (1 = minimum, 5 = maximum).

The pilot study of the questionnaire was applied to 10 medical students and favourable results were obtained. At the

beginning of a PBL session in February 2002, the ques- tionnaire was distributed to first and third-year students and

collected 15 minutes later. Before the application of

Page 3 of 7 (page number not for citation purposes) the questionnaire, the purpose of the study was briefly explained

to the students and their oral consents were obtained.

The response rate was 78.8% (115/146) for first-year stu- dents and 85.5% (142/166) for third-year students.

SPSS 10.0 for Windows was used and the reliability coef- ficient was calculated (Cronbach alpha: 0.81). Chi-Square

Test was used to investigate students' frequency of use of learning resources. Independent Samples T Test was used

to compare the scores of self-study and reporting proc- esses of both classes. The effects of independent variables on

the breadth and depth of discussion were analysed with Multiple Regression Analysis Test.

Results The weekly self-study times of the first and third-year stu- dents during a two-week module were 15.00 ±

8.83 and 11.57 ± 7.04 hours respectively (p = 0.001).

The first and third-year students' percentages of learning resources usage and statistical difference between them

were respectively as follows; textbooks 24.3% and 44.4% (χ2 = 11.1, p = 0.01), educational CDs 14.8% and 6.3%

(χ2 = 4.983, p = 0.026), lecture handouts 95.7% and 95.8% (χ2 = 0.002, p = 0.962) and medical journals 8.7% and

9.9% (χ2 = 0.102, p = 0.750). Lecture handouts were used very frequently. It was found that third-year students

referred more frequently to textbooks than first-year students.

The scores reflecting students' perceptions of statements regarding learning issue driven searching and extensive-

ness of searching ranged between 3.4–3.7 out of five (Table 1). Third-year students' scores for the same state- ments

were higher than those of first-year students' (p = 0.034, p = 0.009). First-year students' average scores on

explanation-oriented preparing of learning issues were higher than those of third-year students' (p = 0.015).

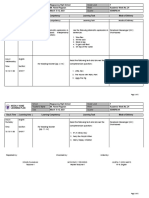

Table 1: First and third-year students' average scores regarding self-study process

Titles First-year students average

score* ± SD

Third-year students average score* ± SD

Statistical analysis**

Learning issue driven preparing 3.5 ± 0.8 3.7 ± 0.8 P = 0.034 Extensiveness of searching 3.4 ± 0.9 3.7 ± 0.9 P =

0.009 Explanation-oriented preparing 3.5 ± 0.6 3.3 ± 0.7 P = 0.015

* (1 = minimum, 5 = maximum) ** Independent samples T test.

BMC Medical Education 2004, 4:16 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16

Table 2: First and third-year students' average scores on discussion during reporting phase

Titles First-year students' average

Third-year students' average score* ± SD

score* ± SD

Page 4 of 7 (page number not for citation purposes) Statistical analysis**

Breadth of discussion 3.3 ± 0.8 3.2 ± 0.9 P = 0.345 Depth of discussion 3.7 ± 0.7 3.4 ± 0.8 P = 0.000

* (1 = minimum, 5 = maximum) ** Independent samples T test.

Table 3: The effects of the independent variables on the breadth and depth of discussion (Multiple

Regression Analysis)

R2 β t F

Dependent variable: Breadth of discussion

Searching process Learning issue driven searching 0.21 2.97* Extensiveness of searching 0.07 0.96 Preparing

process 0.09 6.976* Explanation-oriented preparing 0.14 1.89* Dependent variable: Depth of discussion Searching

process Learning issue driven searching 0.26 3.87* Extensiveness of searching -0.07 -1.08 Preparing process 0.15

12.377* Explanation-oriented preparing 0.26 3.87*

*p < 0.05

The scores reflecting students' perceptions on statements regarding the discussion of learning objectives during the

reporting phase of a PBL session, ranged between 3.2–3.7 out of five. First-year students' average scores on the

depth of discussion were higher than those of third-year stu- dents' (p = 0. 000) (Table 2).

The effects of learning issue driven searching, extensive- ness of searching and explanation oriented preparing on

the breadth and depth of discussion were analysed with regression analysis (Table 3).

The 9% change in the breadth of discussion was explained with searching and preparing phases. Learning issue

driven searching with the highest β value was the most important and statistically significant factor influencing the

breadth of discussion. The impact of explanation ori- ented preparing on the breadth of discussion was also sta-

tistically significant (Table 3).

The 15% change in the depth of discussion was explained with searching and preparing phases. It was found that

learning issue driven searching and explanation oriented preparing were the most important and statistically signif-

icant factors influencing the depth of discussion. The extensiveness of searching had a statistically insignificant

negative effect on the depth of discussion (Table 3).

Regression analysis was separately carried out for both classes. Excluding the extensiveness of searching, other

findings were similar. Extensiveness of searching had a statistically negative effect on the depth of discussion

among first-year students (β = -0.28, t = -2.680, p = 0.009), but a positive effect among third-year students (β = 136,

t = 2.198, p = 0.030).

Discussion A probable explanation for the relative shortness of third- year students' self-study times compared with

those of first-year students' was third-year students' mental weari- ness due to continuous and intensive effort in

reaching learning objectives. Another probable explanation was first-year students' slowness in accessing

appropriate resources due to their lack of familiarity with self-directed learning.

It was found that first and third-year students frequently used lecture handouts. The reasons for the high frequency

BMC Medical Education 2004, 4:16 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16

of use of handouts were considered as their wide availabil- ity due to their provision at the end of lectures that are

limited to one hour a day. In order not to hinder the curi- osity of students and their motivation for self-directed

learning, handouts are designed as brief outlines prepared by lecturers and include topic titles, schemata, algorithms

and tables.

Since the Learning Resources Centre was inaugurated in 2001, third year students could only use it during their

second and third years, whereas first-year students started using it since the beginning of their medical education.

More frequent use of Learning Resources Centre CDs by first-year students may be related to their early encounter

with these learning facilities.

Third-year students' more frequent use of textbooks may reflect the development of their ability in reaching essen-

tial resources.

Third-year students' higher ratings for learning issue driven searching and extensiveness of searching are con- sistent

with the general expectation stating that experi- enced students can search more learning resources [4]

The first-year students attributed higher scores to state- ments regarding explanation oriented preparing (Table 1).

This finding may be explained with third-year stu- dents' mental weariness due to continuous and intensive efforts

since the beginning of their medical education or first-year students' eagerness to adapt to a new educa- tional

system.

In the Maastricht study, first-year students' average scores for learning issue driven searching, extensiveness of

searching and explanation oriented searching were 3.1 ± 0.3, 2.8 ± 0.4 and 3.2 ± 0.3 respectively [6].

The scores of the entire study group attributed to breadth and depth of discussion during the reporting phase varied

between 3.2 ± 0.9 and 3.7 ± 0.7. Although third-year stu- dents were expected to become more competent in PBL

discussions, third-year students' scores, especially the ones attributed to the depth of discussion, were lower than

those of first-year students' (Table 2). This finding is consistent with Cohen's view that the students who gain

experience in cooperative study are inclined to limit their efforts to share and explain the information they gather

[9]. Higher scores of first-year students on the depth of discussion may also be interpreted as a reflection of their

adaptation to the PBL system. In the Maastricht study, average scores attributed by first-year students to the breadth

and depth of discussion were 3.0 ± 0.4 and 3.4 ± 0.5 respectively [6]

Page 5 of 7 (page number not for citation purposes) The results of this study showed that the breadth of discus- sion

during reporting phase was affected by the searching and preparing phases of the self-study process. Similarly, it

was understood that the depth of discussion during the reporting phase was affected by the searching and prepar- ing

phases of self-study process. Learning issue driven searching "using learning objectives as study references" and

explanation oriented preparing "studying and summarising learning resources at an appropriate level to be shared

with other students during PBL session", directly influenced the breadth and depth of discussion.

It was observed that students' searching of different resources (extensiveness of searching), though not statisti- cally

significant, negatively affected the depth of discus- sion. During a PBL session, in the presence of different

resources, in-depth understanding of newly acquired information requires a well-structured discussion. This may be

difficult for first-year students due to their lack of familiarity with PBL and self-directed learning. In the group

session, first-year students may encounter difficul- ties while tutoring a discussion based on several resources [6].

When regression analysis was separately carried out for both classes, it was observed that extensiveness of searching

had a statistically negative effect on the depth of discussion among first-year students, but a positive effect among

third-year students. These findings imply that the increase in students' PBL experience paralleled the devel- opment

of their discussion skills using different learning resources.

The design of the present study based on students' percep- tions was its main limitation. The assumptions regarding

the causes of differences between first and third-year stu- dents' perceptions were based on the PBL experience of

authors.

Conclusions First-year students' longer self-study times, higher expla- nation oriented preparing scores, and higher

depth of dis- cussion scores compared with the scores of third-year students were considered as research questions

which need to be investigated in future studies.

Competing interests None declared.

Authors' contributions BM carried out research design, statistical data analysis, data evaluation, research report, YG

carried out research design, data evaluation, research report, HCT carried out data evaluation and research report,

SO carried out data evaluation and contributed to the research report, AT con- tributed to research design, data

collection and data eval-

BMC Medical Education 2004, 4:16 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16

uation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

List of abbreviations DEUSM: Dokuz Eylul School of Medicine

PBL: Problem-based Learning

Appendix Self-study and Reporting Processes Questionnaire

Year: 1 □ 3 □

• What is your weekly average study time in a two-week module?

(..............) hours.

• What kind of resources do you use during your self- study process?

() Textbook () Lecture handouts () Others .....................

() Educational CDs () Medical journals

• Please indicate your level of agreement with the fol- lowing statements about self-study process, by rating

them between 1-to-5.

(1 = totally disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = totally agree)

12345

Search Phase

Learning Issue Driven Searching

1. I use the learning issues as a starting point for my search and search the resources accordingly.

During studying

2. I always check the learning issues to decide whether I study deep enough.

3. I remain attached to the learning issues.

4. I check the learning issues to decide whether the resources I study fully cover the learning issues.

5. I use the learning issues as a guide while studying the resources step by step.

Extensiveness of searching

Page 6 of 7 (page number not for citation purposes) 6. When searching the resources, I try to evaluate the rele-

vancy of different books with the subject to be studied.

7. When searching the resources, I try to compare different resources about the same subject.

8. I spent a lot of time and effort on searching the resources before I start studying

Preparing phase

Explanation Oriented

9. I study the subjects such that I can explain them without looking at the resources.

10. I study the subjects such that I can comment about the theories being discussed

11. I study such that I can explain the content of the resource in my own words.

12. I study such that I know what needs to be discussed in each learning issue.

13. I study by making summaries of the selected resources.

14. I study by making notes and algorithms.

Reporting Phase

Breadth of Discussion

15. Many different issues/findings are discussed.

16. When a student from the group reaches an informa- tion not included in the learning issues explains it to others.

17. The members of the group question different aspects of the resources.

18. Different/contradicting resources are compared.

Depth of Discussion

19. During discussions new concepts are discussed and explained in detail.

20. The issues are discussed in depth.

21. The problems of the scenario are questioned and clar- ified using the newly learned knowledge.

BMC Medical Education 2004, 4:16 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16

22. The discussion in the reporting makes very useful con- tributions to newly learned knowledge in the self-study

process.

Acknowledgements Linda Distlehorst, Chair of Medical Education Department, Southern Illi- nois School of Medicine,

for her review and constructive comments.

References 1. Barrows HS, Tamblyn RB, (Eds): Problem-Based Learning, An Approach to Medical Education.

New York: Springer; 1980:98-99. 2. Schmidt HG: Onderwijskundige specter van probleemgestu- urd onderwij

(Educational aspects of problem-based learn- ing). In Activerend onderwijs Edited by: Joshes WMG. Delft:

Delftse Universitaire Pers; 1990:1-16. 3. Schmidt HG: Problem-based learning: rationale and

description. Med Educ 1983, 17:11-16. 4. Van den Hurk MM, Wolfhagen IHAP, Dolmans DHJM, Van der Vleu-

ten CPM: The impact of student-generated learning issues on individual study time and academic achievement. Med

Educ 1999, 33:808-814. 5. Deretchin LF, Yeoman LC, Seidel CL: Student information resource utilization in

problem-based learning. Med Educ Online 1998, 4:7 [http://www.med-ed-online.org/res00006.htm#top]. 6. Van den

Hurk MM, Dolmans DHJM, Wolfhagen IHAP, Muijtjens AMM, Van der Vleuten CPM: Impact of Individual Study on

Tutorial Group Discussion. Teach Learn Med 1999, 11(4):196-201. 7. Premkumar K, Baumber JS: A learning

resources centre: its uti-

lization by medical students. Med Educ 1996, 30:405-411. 8. Musal B, Abacioglu H, Dicle O, Akalin E,

Sarioglu S, Esen A: Faculty development programs in Dokuz Eylül University School of Medicine: In the

process of curriculum change from tradi- tional to PBL. Med Educ Online (serial online) 2002, 7:2 [http://

www.med-ed-online.org/pdf/res00030.pdf]. 9. Cohen EG: Restructuring the classroom: Conditions for pro-

ductive small groups. Review of Educational Research 1994, 64(1):1-35.

Pre-publication history The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/4/16/prepub

Publish with Bio Med Central and every scientist can read your work free of charge

"BioMed Central will be the most significant development for disseminating the results of biomedical research in our

lifetime."

Sir Paul Nurse, Cancer Research UK

Your research papers will be:

available free of charge to the entire biomedical community

peer reviewed and published immediately upon acceptance

cited in PubMed and archived on PubMed Central

yours — you keep the copyright

Submit your manuscript here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/publishing_adv.asp

Page 7 of 7 (page number not for citation purposes)

BioMedcentral

You might also like

- Making a Stand on Key IssuesDocument35 pagesMaking a Stand on Key Issuesbuena rosario100% (11)

- Skit Script (Child)Document7 pagesSkit Script (Child)singhaliti100% (5)

- Area Statement SchoolDocument1 pageArea Statement SchoolHarsh GuptaNo ratings yet

- GTE JomariDocument10 pagesGTE JomariLisly Dizon100% (1)

- 1472 6920 4 16 PDFDocument7 pages1472 6920 4 16 PDFRiana RurmanNo ratings yet

- BMC Medical Education: Student Approaches For Learning in Medicine: What Does It Tell Us About The Informal Curriculum?Document23 pagesBMC Medical Education: Student Approaches For Learning in Medicine: What Does It Tell Us About The Informal Curriculum?delap05No ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning & Task-Based Learning Curriculum Revision Experience of A Turkish Medical FacultyDocument4 pagesProblem-Based Learning & Task-Based Learning Curriculum Revision Experience of A Turkish Medical FacultyalhanunNo ratings yet

- Superficial and Deep Learning Approaches Among Medical StudentsDocument5 pagesSuperficial and Deep Learning Approaches Among Medical Studentsq234234234No ratings yet

- Walankar (2019)Document11 pagesWalankar (2019)Andy Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- Canadian Medical Education JournalDocument4 pagesCanadian Medical Education JournalannegirlNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Learning Preferences (Styles and Approaches) and Learning Outcomes Among Pre-Clinical Undergraduate Medical StudentsDocument7 pagesThe Relationship Between Learning Preferences (Styles and Approaches) and Learning Outcomes Among Pre-Clinical Undergraduate Medical StudentsCindy JANo ratings yet

- How Do Students' Perceptions of Research and Approaches To Learning Change in Undergraduate Research?Document9 pagesHow Do Students' Perceptions of Research and Approaches To Learning Change in Undergraduate Research?Ester RodulfaNo ratings yet

- Module 5Document20 pagesModule 5Cyrus NadaNo ratings yet

- GetfileDocument25 pagesGetfileEaint Myet ThweNo ratings yet

- Modern Techniques of TeachingDocument16 pagesModern Techniques of TeachingVaidya Omprakash NarayanNo ratings yet

- There's A Lot of Learning Going On But NOT Much Teaching!': Student Perceptions of Problem-Based Learning in ScienceDocument17 pagesThere's A Lot of Learning Going On But NOT Much Teaching!': Student Perceptions of Problem-Based Learning in ScienceNur Amani Abdul RaniNo ratings yet

- 10 11648 J Edu 20200905 11Document5 pages10 11648 J Edu 20200905 11mergamosisa286No ratings yet

- A. Bilime Katki: Araştirmaya Dayali Yayinlar, Bilimsel Projeler, Editörlük, HakemlikDocument95 pagesA. Bilime Katki: Araştirmaya Dayali Yayinlar, Bilimsel Projeler, Editörlük, HakemlikNursen Özdemir İlçinNo ratings yet

- Open Journal of Social SciencesDocument8 pagesOpen Journal of Social SciencesMónica María AlfonsoNo ratings yet

- Students ' Perceptions Towards Self-Directed Learning in Ethiopian Medical Schools With New Innovative Curriculum: A Mixed-Method StudyDocument10 pagesStudents ' Perceptions Towards Self-Directed Learning in Ethiopian Medical Schools With New Innovative Curriculum: A Mixed-Method StudyMiss LNo ratings yet

- Full Blown Reasearch G4Document68 pagesFull Blown Reasearch G4anarose losanoyNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingDocument6 pagesProblem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingArdianNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Research in NursingDocument11 pagesCurriculum Research in Nursingesther100% (5)

- Latest Research Docx Teshale Wirh Cfwork - For MergeDocument23 pagesLatest Research Docx Teshale Wirh Cfwork - For MergeTeshale DuressaNo ratings yet

- Articles Pedagogies of Engagement in ScienceDocument12 pagesArticles Pedagogies of Engagement in ScienceElke Annisa OctariaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Problem Based Learning in Increasing Understanding of Health Data Processing Management SubjectDocument7 pagesEffectiveness of Problem Based Learning in Increasing Understanding of Health Data Processing Management SubjectAgus RiyantoNo ratings yet

- EJ1318936Document14 pagesEJ1318936Wynonah Merie MendozaNo ratings yet

- How Effective Is Inquiry-Based Learning in Linking Teaching and Research?Document7 pagesHow Effective Is Inquiry-Based Learning in Linking Teaching and Research?Anonymous rUr4olUNo ratings yet

- Ijrp-Format - For-Publication - Diana Len-CandanoDocument16 pagesIjrp-Format - For-Publication - Diana Len-CandanoDiana Bleza CandanoNo ratings yet

- Student Centered Learning: An Insight Into Theory and PracticeDocument47 pagesStudent Centered Learning: An Insight Into Theory and PracticeNadia Fairos100% (1)

- The Relationship Between Learning Preferences (Styles and Approaches) and Learning Outcomes Among Pre-Clinical Undergraduate Medical StudentsDocument7 pagesThe Relationship Between Learning Preferences (Styles and Approaches) and Learning Outcomes Among Pre-Clinical Undergraduate Medical Studentsm-6867011No ratings yet

- Tutoría Entre Iguales en Una Escuela de Medicina Percepciones de Tutores y TutoradosDocument7 pagesTutoría Entre Iguales en Una Escuela de Medicina Percepciones de Tutores y TutoradosFalconSerfinNo ratings yet

- Commentary PaperDocument5 pagesCommentary PaperJohn Paul JerusalemNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning Process To Enhance Teaching Effectiveness: A Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesTeaching and Learning Process To Enhance Teaching Effectiveness: A Literature ReviewJoy Amor ManoNo ratings yet

- Chapters1 4 FinalDocument77 pagesChapters1 4 FinalDarlene OcampoNo ratings yet

- Harden's Spices Model For Biochemistry in Medical CurriculumDocument10 pagesHarden's Spices Model For Biochemistry in Medical CurriculumGlobal Research and Development Services100% (1)

- Group 5 NDocument46 pagesGroup 5 NmarkixhielNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Contextualization (Icon) As Teaching Strategy That Helps Elevate Students' Learning in ScienceDocument1 pageInterdisciplinary Contextualization (Icon) As Teaching Strategy That Helps Elevate Students' Learning in ScienceMaribel FajardoNo ratings yet

- Blended-Problem-Based Learning: How Its Impact On Students' Critical Thinking Skills?Document10 pagesBlended-Problem-Based Learning: How Its Impact On Students' Critical Thinking Skills?Anisa Saskia Laily PriyantiNo ratings yet

- To Evaluate Students' Perceptions On Teaching Styles at Basic Sceinces Departments of Services Institute of Medical Sciences, LahoreDocument10 pagesTo Evaluate Students' Perceptions On Teaching Styles at Basic Sceinces Departments of Services Institute of Medical Sciences, LahoreFatima MNo ratings yet

- Wa - 5Document27 pagesWa - 5VineetaNo ratings yet

- Application of Theories Principles and Models of Curriculum Munna and Kalam 2021Document7 pagesApplication of Theories Principles and Models of Curriculum Munna and Kalam 2021Vaughan LeaworthyNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Learning at The Polytechnic University: Interactive Classroom TechniquesDocument12 pagesEnhancing Learning at The Polytechnic University: Interactive Classroom TechniquesRinandar MusliminNo ratings yet

- Caroline E. Morton 2016Document8 pagesCaroline E. Morton 2016Jejak Nusantara KuNo ratings yet

- Local Research FinalDocument3 pagesLocal Research Finalsophian0907No ratings yet

- Nursing Students' Perceptions Towards Flipped Classroom Educational Strategy.Document14 pagesNursing Students' Perceptions Towards Flipped Classroom Educational Strategy.Mariana NannettiNo ratings yet

- Learner-Centered Instruction in Pre-Service Teacher Education: Does It Make A Real Difference in Learners' Language Performance?Document14 pagesLearner-Centered Instruction in Pre-Service Teacher Education: Does It Make A Real Difference in Learners' Language Performance?Pratama AhdiNo ratings yet

- ChapterI - ExampleOnly v.1Document19 pagesChapterI - ExampleOnly v.1Sample PleNo ratings yet

- Sarahknight, Cocreation of The Curriculum Lubicz-Nawrocka 13 October 2017Document14 pagesSarahknight, Cocreation of The Curriculum Lubicz-Nawrocka 13 October 2017陳水恩No ratings yet

- Additional Reading 1Document18 pagesAdditional Reading 1KNo ratings yet

- Towards An Effective Language Learning Styles, Strategies and Teaching Methods: An Investigative Research Based On Multicultural - EAL Primary PupilsDocument78 pagesTowards An Effective Language Learning Styles, Strategies and Teaching Methods: An Investigative Research Based On Multicultural - EAL Primary PupilsNguyễn Kim AhnNo ratings yet

- 3e and 5e Model Education-6-1-12Document7 pages3e and 5e Model Education-6-1-12AragawNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning in Clinical Practice: Employment and Education As Development PartnersDocument8 pagesProblem-Based Learning in Clinical Practice: Employment and Education As Development PartnersAyu FadhilahNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning in The Educational System of Bolu (Turkey)Document10 pagesProblem-Based Learning in The Educational System of Bolu (Turkey)Centro Studi Villa MontescaNo ratings yet

- Sample ProposalDocument67 pagesSample ProposalGiancarla Maria Lorenzo Dingle100% (1)

- Comparing Problem Based Learning With Lecture Based Learning On Medicine Giving Skill To Newborn in Nursing StudentsDocument7 pagesComparing Problem Based Learning With Lecture Based Learning On Medicine Giving Skill To Newborn in Nursing StudentsWanda AstariNo ratings yet

- Fostering Effective Learning Strategies in Higher EducationDocument18 pagesFostering Effective Learning Strategies in Higher Educationjefford torresNo ratings yet

- Good HolyDocument22 pagesGood HolySherwin CarinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter IDocument12 pagesChapter Ijoebert esculturaNo ratings yet

- English Language Journal Vol 4, (2011) 99-113 ISSN 1823 6820Document13 pagesEnglish Language Journal Vol 4, (2011) 99-113 ISSN 1823 6820Mohd Zahren ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Combining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementDocument13 pagesCombining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementJuan Augusto Fernández TarazonaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Primary ScienceDocument295 pagesTeaching Primary ScienceNOENo ratings yet

- MR ChintuDocument4 pagesMR Chintupeter malembekaNo ratings yet

- Connected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeFrom EverandConnected Science: Strategies for Integrative Learning in CollegeTricia A. FerrettNo ratings yet

- Patent Ductus Arteriosus: Pathophysiology and Management: Original ArticleDocument10 pagesPatent Ductus Arteriosus: Pathophysiology and Management: Original ArticleYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Amiodarone, Lidocaine, or Placebo in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac ArrestDocument12 pagesAmiodarone, Lidocaine, or Placebo in Out-of-Hospital Cardiac ArrestRifqi UlilNo ratings yet

- Gold 2019 Pocket Guide Final WmsDocument49 pagesGold 2019 Pocket Guide Final WmsFrensi Ayu PrimantariNo ratings yet

- Decompression Sickness and Recreational Scuba Divers: Original ArticleDocument3 pagesDecompression Sickness and Recreational Scuba Divers: Original ArticleYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Bahan Ajar 4 FenilketonuriaDocument8 pagesBahan Ajar 4 FenilketonuriaNur FadhilaNo ratings yet

- A Case of Decompression Illness Not Responding To Hyperbaric OxygenDocument4 pagesA Case of Decompression Illness Not Responding To Hyperbaric OxygenYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Definitions and Goals of "Self-Directed Learning" in Contemporary Medical Education Literature N Ainoda, 1Document12 pagesDefinitions and Goals of "Self-Directed Learning" in Contemporary Medical Education Literature N Ainoda, 1Riana RurmanNo ratings yet

- A Case of Decompression Illness Not Responding To Hyperbaric OxygenDocument4 pagesA Case of Decompression Illness Not Responding To Hyperbaric OxygenYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Comparing Communication Skills of Activist and Non-Activist Medical StudentsDocument3 pagesComparing Communication Skills of Activist and Non-Activist Medical StudentsAnisa Kurniadhani SuryoNo ratings yet

- p2211 PDFDocument8 pagesp2211 PDFYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Citicoline On Acute Ischemic Stroke A ReviewDocument6 pagesThe Effects of Citicoline On Acute Ischemic Stroke A ReviewSarah HabibahNo ratings yet

- LeMaitre J Sport Sci 27 1519 1534 2009 - 60803Document17 pagesLeMaitre J Sport Sci 27 1519 1534 2009 - 60803Yanny LabokNo ratings yet

- RD_HTTMAR06_p17_20.qxd 2/2/06 10:45 AM Page 17Document4 pagesRD_HTTMAR06_p17_20.qxd 2/2/06 10:45 AM Page 17Yanny LabokNo ratings yet

- p2211 PDFDocument8 pagesp2211 PDFYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Decompression Sickness Cases Treated WitDocument5 pagesDecompression Sickness Cases Treated WitYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- The Probability and Severity of Decompression Sickness: A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111Document25 pagesThe Probability and Severity of Decompression Sickness: A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111 A1111111111Yanny LabokNo ratings yet

- 21 EdDocument5 pages21 EdYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- JCN 14 487Document5 pagesJCN 14 487Yanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Zandi2011 Article Disease-relevantAutoantibodiesDocument3 pagesZandi2011 Article Disease-relevantAutoantibodiesYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Penda Hulu AnDocument1 pagePenda Hulu AnYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Meningitis FAQs: Causes, Symptoms & PreventionDocument3 pagesMeningitis FAQs: Causes, Symptoms & PreventionSilverius Seantoni SabellaNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument5 pagesCase ReportYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- JCN 14 487Document5 pagesJCN 14 487Yanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Education 4 6 3 PDFDocument9 pagesEducation 4 6 3 PDFYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Acute Subdural HematomaDocument1 pageTraumatic Acute Subdural HematomaYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument5 pagesCase ReportYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- 21 EdDocument5 pages21 EdYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Pemba Has AnDocument3 pagesPemba Has AnYanny LabokNo ratings yet

- Digital Unit Plan Template Unit Title: Exploring Evolution and Organism Name: Ronnie Nguyen Content Area: Biology Grade Level: 9Document4 pagesDigital Unit Plan Template Unit Title: Exploring Evolution and Organism Name: Ronnie Nguyen Content Area: Biology Grade Level: 9api-280913365No ratings yet

- Research Title Ni PogiDocument8 pagesResearch Title Ni PogiAngelo Lirio InsigneNo ratings yet

- DLPSALOMSDocument6 pagesDLPSALOMSEllieza Bauto SantosNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH-10 Q3 Mod4.1 USLeM-RTP-AdvanceDocument9 pagesENGLISH-10 Q3 Mod4.1 USLeM-RTP-AdvanceMikaella Jade MempinNo ratings yet

- Algorithms Abstractions and Iterations Teaching Computational Thinking Using Protein Synthesis TranslationDocument9 pagesAlgorithms Abstractions and Iterations Teaching Computational Thinking Using Protein Synthesis TranslationGülbin KiyiciNo ratings yet

- A Sen Justice and Rawls ComparisonDocument16 pagesA Sen Justice and Rawls Comparisonrishabhsingh261100% (1)

- Itinerary LICODocument2 pagesItinerary LICOAaron James LicoNo ratings yet

- English Teaching in ColombiaDocument4 pagesEnglish Teaching in Colombiafernanda sotoNo ratings yet

- LESSON PLAN FOR ROOMS AND PARTS OF THE HOUSEDocument8 pagesLESSON PLAN FOR ROOMS AND PARTS OF THE HOUSEJohn RamirezNo ratings yet

- Full Download Ebook PDF Human Communication 7th Edition by Judy Pearson PDFDocument41 pagesFull Download Ebook PDF Human Communication 7th Edition by Judy Pearson PDFwilliam.decosta187100% (36)

- IQ Test Questions With Answers - Brain Teasers & PuzzlesDocument5 pagesIQ Test Questions With Answers - Brain Teasers & PuzzlesjohnkyleNo ratings yet

- Domain 2 - The Classroom EnvironmentDocument7 pagesDomain 2 - The Classroom Environmentapi-521599993No ratings yet

- Assignment of MFTLDocument18 pagesAssignment of MFTLAsia SultanNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 9.unit 6 Aim HIgh 4Document4 pagesLesson Plan 9.unit 6 Aim HIgh 4Ahmet KoseNo ratings yet

- Tid Bits of Wisdom July & August 2023Document6 pagesTid Bits of Wisdom July & August 2023Tidbits of WisdomNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan on Thesis StatementsDocument4 pagesDaily Lesson Plan on Thesis StatementsKanon NakanoNo ratings yet

- Klasifikasi Pasien 1Document7 pagesKlasifikasi Pasien 1syofwanNo ratings yet

- Global CityDocument34 pagesGlobal Citychat gazaNo ratings yet

- Admission Manual 2023 24Document22 pagesAdmission Manual 2023 24Surajit RayNo ratings yet

- Week 24 WHLP-REMEDIATION-7-PagaranDocument2 pagesWeek 24 WHLP-REMEDIATION-7-PagaranRoniel PagaranNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Map - Math 6 q3Document3 pagesCurriculum Map - Math 6 q3Dhevy LibanNo ratings yet

- QualityDocument54 pagesQualityvcoolfoxNo ratings yet

- DepEd Cebu Health RecordsDocument5 pagesDepEd Cebu Health RecordsHyacinth Eiram AmahanCarumba LagahidNo ratings yet

- A Business Plan for a Multiple Intelligence SchoolDocument48 pagesA Business Plan for a Multiple Intelligence SchoolAilyn VillaruelNo ratings yet

- Cesc-Week 3 Lesson 5Document36 pagesCesc-Week 3 Lesson 5Janica Mae MangayaoNo ratings yet

- Resource-Based Theories of Competitive Advantage: A Tenyear Retrospective On The Resource-Based ViewDocument9 pagesResource-Based Theories of Competitive Advantage: A Tenyear Retrospective On The Resource-Based Viewxaxif8265No ratings yet