Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Between Legibility and Ambivalence

Uploaded by

Теодора БјелићOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Between Legibility and Ambivalence

Uploaded by

Теодора БјелићCopyright:

Available Formats

Four Acts: Between Legibility and

Ambivalence

Architectural timelines are often marked by new acts in the theatre of form.

Over the last 30 years this theatre has witnessed post-modernism’s applique

of historical references, the heterogeneous, fragmented, and contradictory

forms of deconstruction, and is likely most notable for the supple, pliant forms

of blobs, folds, topological surfaces, and computational techniques. During this

same time period two categories of historic divide became more apparent.

CLARK THENHAUS THE THEATER OF FORM

University of Michigan The divide between the expanded field and autonomous formalism has become

increasingly apparent in relation to emerging technologies as a territorial practice

and a digital project. This polemic is marked on one hand by a geographic and

territorial model of relations influenced by socio-economic, environmental, and

political forces with an aim to integrate ecological systems, infrastructural net-

works, and social collectives staked against ‘form hunters’.1 On the other hand,

the digital project staked a claim to technology’s capacity to reinstate disciplinary

expertise and customization as aesthetic, geometric data-managing, and ideo-

logical drivers. In the expanded field of relations, the terms and conditions of net-

working, connectivity, and systemization re-located a disciplinary and historical

project of architectural form-making to consequences of political, infrastructural,

or environmental forces. In the digital project, the same culturally pervasive

terms of the times, networks and systems, served as both internal relational

protocols with aesthetic demonstrations of complexity (honeycombs, Voronoi’s,

Delauny meshes, etc) and a predominant concentration on digital virtuosity with

the appearance of networks and interconnectedness, a calling card for a time

marked by technique, connectivity, fields, and fineness.2 Even with the exclusion

of the social and political dimension, networks and connectivity were built into

the protocols, aesthetics, and digital techniques themselves.3 Bob Somol articu-

lates this distance between territorial practice as characterized by ‘politics +

environment’ and digital formalism as ‘science + fiction’.4 Thus, relationism can

be understood as linkages between a presumed concreteness of geographic or

environmental correlations of data and material infrastructure with rational or

‘consequential’ outcomes.5 Meanwhile, the digital project, with all its complex-

ity and aesthetics aimed at high and fine fidelity with a demonstrated virtuosity

of techniques and effects, lacks the disciplinary traction it once had and it seems

unlikely that further refinement and fidelity will reclaim the original inertia. As a

discipline, having largely, though not wholly, skirted explicit discussions on form

119 The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center

in favor of networks, infrastructure, systems, and fields and having also mastered

topological complexity, component differentiation, gradation, and computational

and tectonic intricacy, it seems appropriate to ask what are alternatives for a

contemporary formalism; one marked not by relational externalities or by dem-

onstrations of digital fidelity? This question seems appropriate as attention to

objects, history, figure, coarseness, volume, and association appear to be usher-

ing out the last two or three decades of work dedicated to fields, invention, net-

works, elegance, surface, and sensation.6

The following text aims to engage new modes of architectural thought dedi-

cated to form in a post-digital era. This is done with a goal to dove-tail post-dig-

ital formalism with emerging disciplinary and ideological shifts that go Beyond

Relationism. The emphasis on form suggests a model of architectural production

in which “we do not bring forms into contact with their ground by stewing on and

on about whom they might pillage and exploit. We do it by detaching forms from

the superficial relations in which they become entangled, thus enabling reso-

nance between figure and ground.”7 This further suggests that architectural form

can be non-relational yet identify with a context, or ground. Specifically, atten-

tion is called to distinctions between legible and ambivalent form in an effort to

appropriate these terms, in what I am calling operative form, which aims to “con-

tinue disciplinary formalism by fusing classical knowledge with emerging [exist-

ing] technologies.”8

ACT 1: FORMAL LEGIBILITY & AMBIVALENCE

Let us first differentiate legible from literal. Literal form would be, as popular-

ized by Robert Venturi and the Long Island Duck building, a literal representa-

tion without metaphor, allegory, or visual abstraction. This does not, however,

make legible form simply the ducks other, the decorated shed with tacked on

cues indicative of use.9 Rather, legibility is graphic, expedient, illicit, and auto-

matic independent of historical cues, explicit signage, or literal representation.

Claiming shapes are ’crude, fast, and explicit’ in 12 Reasons To Get Back Into

Shape Bob Somol describes that graphic expediency has the capacity to com-

municate quickly among diverse audiences, and this has the capacity to convene

new social collectives. This is not entirely dissimilar from Nicolas Bourriaud’s

Relational Aesthetics (1998) where “…convivial aesthetics [or] an art that draws

people from their introverted and alienated reveries and forces interaction

between them.”10 The ‘graphic’ is characterized by shapes and may be easily rec-

ognized by strong figural profiles or figural sections11 allowing direct and immedi-

ate legibility of visual and cognitive access.12 On the other hand, an expressive

mass offers the possibility for subjective [mis]-readings and cognitive ‘error’,

thereby clearing room for qualitative interpretations based primarily on aesthetic

and spatial experience. This condition operates at a slower, non-automatic speed

of reception and is capable of provoking differences among subjective percep-

tions. As Le Corbusier wrote in the introduction to Towards A New Architecture,

“mass is the element by which our senses perceive and measure and are most

fully affected.”13 Whereas shape has something to do with graphic familiarity and

recognition, an expressive mass has something to do with spatial perception and

experience.

Colin Rowe claimed that “when considering intercourse with a building, its face,

however veiled, must always be a desirable and provocative item.”14 Heinrich

Wolfflin, however, favored bodies and association, claiming “with head and

foot, back and front: We can comprehend the dumb imprisoned existence of a

Beyond Relationism Four Acts: Between Legibility and Ambivalence 120

bulky, memberless, amorphous, conglomeration, heavy and immovable, as

easily as the fine and clear disposition of something delicate and lightly articu-

lated.”15 While Rowe assigns primacy to the face, or façade, Wolfflin speaks of

the attendant qualities of bodies; weight, height, stability all pointing to issues of

posture, figure, and association. Yet, in George Simmel’s 1907 book The Aesthetic

Significance of the Human Face he wrote “Bodies differ to the trained eye just

as faces do; but unlike faces, bodies do not at the same time interpret these dif-

ferences.”16 Simmel also coined the phrase “the face is the mirror to the soul.”17

This is important as it recognizes the face as the bearer of meaning or feeling felt

from within and signals, as Lacan notes of mirrors, a critical self-awareness as a

state of personal reflection and expression. Rowe combines the face, or façade,

with the soul, or interior, by stating the façade represents “internal animation,

both opaque and revealing.”18 For Rowe, the façade was a register and a repre-

sentation of, or responsive to, internal functions, like that of Simmel’s face or

Lacan’s mirror. As Simmel and Wolfflin speak of the human face or body, Rowe

appropriates these qualities more directly to architecture. In this appropriation,

the graphic qualities of shape outlined by Somol and those of face, or façade by

Rowe, find commonality. From this we can generally understand legible form as

that which can be immediately oriented, read facially, and is graphically acces-

sible. Or, as characterized by 1) graphic frontality, 2) emphasis on facade, 3) fig-

uration and shape-based profiles 4) interior registration on the exterior (spatial

‘tell’), and 5) shared readings or interpretations.

It’s interesting to recall Sigfried Giedion’s claim that “the routine misuse of

shapes from the past, the devaluation of traditional language, [initiates] a loss

of monumentality attributable to no ‘special political or economic system.’”19

Perhaps accepting such ‘misuse’ offers a bridge to ambivalent form.

Firstly, ambivalence is careful, not carefree. To be carefree is to be indifferent.

Ambivalence is more cunning in the composition of form and locates issues of

reception between a subjective pre-existing familiarity with identifiable qualities

and its potential gestalt, or reading as something other, as a spatial and cultural

project. Ambivalence frustrates the recognition of something by appearing as

two or more things at once, while indifference cares equally little for replica as it

does for novelty.

Jason Payne describes ambivalence by stating “the base condition of uncer-

tainty is one thing, but the conscious awareness of this state of being is some-

thing more: ambivalence. To be ambivalent is to choose to be unclear, undecided,

and equivocal.”20 Through calculated comparisons of a disco ball in metaphoric

relation to planetesimals (such as Mars’ moon, Phobos) Payne outlines five prin-

ciples for an ambivalent architectural object; 1) Not a sphere, (but nearly so) 2)

Concavity’s Awkward Influence, 3) Irregular Albedo, 4) Elevational Ambivalence

and 5) Contextual Indifference.21 It’s useful to unpack these principles, starting

with Not a Sphere (but nearly so). For something to be ‘not a sphere, but nearly

so’ automatically preferences rotundity and volume over surface and flat fron-

tality. An object that is nearly spherical sheds a collectively shared identity,

and instead opens up possibilities for alternative readings, experiences, and

associations. Payne uses the deformation of a disco ball in relation to plane-

tesimals and asteroids to make this point, however we might also take it more

literally as spheres and manipulated spheroidal objects as potentially occupi-

able volumes. Concavity’s Awkward Influence, the second principle, is a qual-

ity for scientific classification with regard to planetesimals and asteroids. More

121 The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center

generally, however, it is a condition of an object being inwardly deformed, per-

haps a slumped body, a moons meteoric divot, or a willfully manipulated solid.

Concavity is generally assumed as a result of external force causing inward defor-

mation. However, if we invert this assumed force diagram of concavity, we might

consider concavity as the result of internal voids within an object against which

the exterior pushes or conforms into. This would then make contact with Rowe’s

discussion on the registration of the interior on the exterior. Yet a third possibil-

ity exists where concavity might also be the illusion of inward deformation. For

example, when two spheres intersect they produce a cleft which appears con-

cave despite the convexity of both objects. The third principle, Irregular Albedo,

is the more slippery of the five. In the context of Payne’s research, this principle

is articulated via the reflective effects of a disco ball and the capacities for such

effects to alter, enhance, or stimulate spatial effects and behavior outside the

object itself. This is a more clever atmospheric effect as opposed to an environ-

mental condition normally associated with albedo. The amount of reflectivity, or

albedo, is both symptomatic of the geometry of the nearly spherical mass and

it’s mirrored mosaic tiles (albedo = 1), but also initiates spatial conditions resid-

ing outside the mass itself through its reflective effects. However, Payne also

notes that a lack of reflection or phenomena that are black (albedo = 0) are also

important for the purposes of connecting to the fourth principle, which articu-

lates the difficulties of identifying edges. On this same topic, though not one the

principles of ambivalence, Payne also interestingly notes that a ‘blank’ form, or

blank face if we recall Rowe, “is not absent of affect, not at all. To the contrary

blankened forms convey very strong valence – usually repulsive rather than

attractive…”22 The fourth principle, Elevational Ambivalence, is a condition in

which undevelopable geometries and the lack of orthogonal corners, conditions

normal to typical elevations and orthographic projections, deny the possibility of

constructing an accurate orthographic elevation, one in which geometry is effec-

tively unfolded or projected onto a flat plane. This is both a problem of geometry

and representation, but should not be confused as an object without profile con-

tinuity, as would be the case with, for example, Alberto Giacometti’s face draw-

ing. Rather it’s an impossibility of unrolling the object onto orthographic planes

as one does easily with a cube or Cartesian form. A parallel to this is found in

the numerous types of map projections of the spheroidal Earth with their varying

degrees of geographically ‘factual’ and representational correspondence. Lastly,

Contextual Indifference permits the architectural object to exist without rever-

ence or responsibility to a context. In this way, scales may shift, orientations may

rotate, locations may change, or gravity may or may not exert force. This prin-

ciple elevates the status of the object’s qualities and effects while limiting exter-

nal contingencies that might otherwise to precisely locate the responsibilities and

preconceived receptions of the architectural object.

ACT 2: SPHERES, CONES, AND CYLINDERS

With legibility and ambivalence now outlined, it will be useful to introduce a

much abbreviated discussion on moving from fineness to figures in an effort

to locate a possible post-digital, beyond relationism target. Within many top

schools of architecture in the 1990’s and early 2000’s, coupled with the philo-

sophical borrowings of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, rhizomatic complexity,

folding, topological surfaces, and computation seemingly rendered primitive

solids as mundane as they were largely discarded as simplistic, scooped away

by an epochal style of digital formalism. The digital project of the academy was

heavily invested in the ideologies and aesthetics of systematized fields, fineness,

Beyond Relationism Four Acts: Between Legibility and Ambivalence 122

surface blending and smoothing, and tectonic intricacy. These characterizations

generally represent an overall ambition towards surfaces and seamlessness on

one hand, and ever smaller, more intricate parts in the composition of irreduc-

ible wholes on the other. In the latter, the discipline effectively moved “from an

understanding of the architectural detail as an isolated, fetishized instance within

an otherwise minimal framework...[to one where] in an intricate network there

are not details per se, detail is everywhere, ubiquitously distributed and continu-

ously variegated in collaboration with formal and spatial effects.”23 Intricacy, fine-

ness, and gradation inherently suggest relational fields of connectivity within an

expanded domain of forces that is not entirely dissimilar from those of territorial

practices. Primitive forms, however, inherently concentrate intellectual and aes-

thetic efforts onto volume, association, figure, and, by-comparison to fineness,

coarseness.

Yet, we should proceed with caution and clarity. For, while it’s true that architects

like Frank Gehry used primitive forms as fodder for formal manipulation, it is pre-

cisely the techniques and effects of deformation that locate projects such as the

Vitra Design Museum in the camp of disassociation. Even the Deconstructivist

Architecture24 show exhibited many projects which aggregated, then deformed

and manipulated primitive solids into heterogeneous assemblages.25 The compul-

sion to manipulate these base solids into heterogeneous and disjunctive expres-

sions portraying difference, deformation, and discontinuity locates such work as

tectonically intricate. One might think this could initiate this work as ambivalent

form, however it is precisely the emphasis on formal and compositional compli-

cation, disjunction, discontinuity, and geometric de-familiarization that elides

ambivalence. They become aesthetic ensembles for conveying the perceived

complexity and fragmented status of culture26, locating such work as deconstruc-

tivist, or work operating on oppositional terms of irreconcilable and confronta-

tional stances to architectural history in order to disassemble architecture itself.

In recalling Rowe’s eventual rejection of his own mathematical approach to form

making, evidenced by his introduction to Five Architects or Collage City (with

Fred Koetter), we see a similar disciplinary attitude emerging today, not in aes-

thetic or technique, but in principle. The emphasis on mathematical and compu-

tational virtuosity that was so saturated in the digital culture of the early 2000’s

has wrung itself out and post-digital attitudes towards form, such as legibility and

ambivalence, aim to renew the status of architectural form without an orthodoxy

for code or explicit dedication to digital technique. In this light, having witnessed

the accumulation of novel forms spurred by digital fidelity, it seems more likely

that best suited to operate with a post-digital attitude is not the invention of new

forms, but rather revisiting more humbled ones through today’s discourse and

technologies.

In fact, common to both legibility and ambivalence is explicit use or reference to

known shapes and primitive geometries, namely the sphere. Interestingly, while

ambivalent form would elide the most notable architectural spheres of history,

perhaps belonging to Etienne Boulle’s Newtons Cenotaph, or Claude Nicholas

LeDoux’s House of the Farm Guard, for being too spherical, the terms of legibility

would recall them as an art form as a cultural and political device.27

Curiously, OMA’s 1989 Zeebrugge Sea Terminal proposal sought to produce a

“form that resists classification”28 by combing a sphere atop an inverted cone

with an explicit ambition to “poeticize the pragmatic.” This poeticizing the

123 The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center

ENDNOTES

pragmatic, notably here through strategies of aggregation rather than primitive

singularity, parallels Rowe’s claims for functional expression of the interior on 1 The use of the term ‘form hunter’s refers to Sanford Kwinter’s

dismissal and pejorative remarks concerning form-making,

the exterior, but does so in the spirit of Rossian irreverence to typological formal- articulated in Far From Equilibrium: Essays on Technology and

ism, as noted in the claim that the project resists classification. In this we find the Design Culture. Actar, Barcelona, 2008. 13

potentials of aggregating un-deformed primitives to be a likely scenario where 2 The use of the word Fineness is here used in direct refer-

legibility and ambivalence find an unsuspecting commonality. Unlike the flatness ence to Jesse Reiser’s text, “The New Fineness” published in

Assemblage, 2006. This alludes, as well, to elegance in general,

of cubes and pyramids, or Platonic solids, inherent to spheres, cones, and cylin- captured most prominantly in the discourse of that time in AD

ders is the quality of rotundity. Domes, vaults, arches, and turrets, for example, Elegance (2007) guest edited by Ali Rahim and Hina Jamelle.

In addition, Greg Lynn’s article “Intricacy” directly associates

are products of halved or quartered spheres, cones, and cylinders. From this, we

infinitely small parts with tectonics and aggregations that can

might suspect that with more pluralistic aggregations of spheres, cones, and cyl- arise from digital techniques.

inders, the more rarefied qualities of multivalent cleavages and clefts, bloated yet 3 This is reference to Clement Greenberg work on visual arts that

taut bodies, and voluptuous concavities may become present. Spheres, cones, excluded social aspects but were internally and wholly relational

and cylinders, then, will be the “worthy constraint” that offers the aesthetic within the art piece itself.

validity concentrating on the status of architectural objects, rather than abstract 4 Bob Somol, “What’s Next?” Lecture at University of Kentucky

College of Design. 2011

concepts of external relations29 or internal relational protocols embedded in digi-

tal technique and effect. 5 This is paraphrased from Graham Harman’s “Towards A

Non-Relational Los Angeles; Or How to Free Kwinter from

Whitehead”. http://www.offramp-la.com/towards-non-

ACT 3: OPERATIVE FORM: COUPLING LEGIBILITY AND AMBIVALENCE relational-los-angeles/. Central to this is the dismantling of the

The term operative form is appropriated from Operational Criticism by Bruno idea that these external relations are concrete and therefore

fixed. Rather, Harman articulates it is the concepts that are

Zevi and advanced by Manfredo Tafuri. Operational Criticism was used to “des- themselves the basis for relational thought, not the objects that

ignate a form of history that, by grasping the current significance of the past, constitute the abstraction of relationism

was at one and the same time a form of criticism.”30 Daniel Sherer points out 6 This observation is made by a close read of recent scholarly

that this form of criticism in architecture has been used to manipulate history in essays, journals, and conferences occurring over the last 2

years. In particular the conceptual distance between Log 17

order to extend one’s own agenda or approach, and therefore differs drastically (2007) and Log 31 (2014) serve as evidence in this paradigmatic

from the history of a scholarly historian. In other words, architects edit history in shift. Other publications, such as AD and Project Journal articu-

order to “force the hand” of the present. He also notes, however, “architecture late this shift in recent issues, while a series of conferences and

workshops, including those held in 2013 at Syracuse University,

requires a special mode of criticism – operative criticism – to justify its constitu- the University of Michigan Taubman College of Architecture +

tive strategies and make the semi-conscious apprehension of architecture a mat- Urban Planning and the upcoming ACSA 103 Conference themes

are indicative of the stated position. This is also observed in the

ter of conscious choice.”31 It’s also useful to recall Henry-Russel Hitchcock’s claim growing adoption of Object Oriented Ontology (OOO) as a philo-

that there was a time when looking to history was for the purposes of revival- sophical framework which moves away from external forces and

effects towards qualities of and between objects.

ism, but this is no longer true. Rather, “When we re-examine–or discover–this or

that aspect of earlier building production today, it is with no idea of repeating its 7 Graham Harman, “Towards A Non-Relational Los Angeles; Or

How to Free Kwinter from Whitehead”. http://www.offramp-la.

forms, but rather in the expectation of feeding more amply new sensibilities that

com/towards-non-relational-los-angeles/

are wholly the product of the present.”32 Operative form is therefore concerned

8 Bryony Roberts, « Beyond the Qurelle » in LOG 31 : New

with certain formal lineages and, perhaps, anachronistic geometries wilfully Ancients. Anycorp, 2014. 13-17

adopted under the today’s terms in order to project alternative formal possibili-

9 A point of reference to this claim could be Venturi Rauch

ties that go Beyond Relationsim. Scott Brown’s National College Football Hall of Fame (1967) or

Building-Board. This work used direct language and advertise-

Whereas in the article Architectural Curvilinearity Greg Lynn describes the abil- ment to convey typological or functional content rather than

ity of pliant systems to adapt to contextual, cultural, programmatic, or economic preferrencing geometry and form.

contingencies 33, Graham Harman, in commenting on Sanford Kwinter’s Whose 10 Harman, “Towards A Non-Relational Los Angeles; Or How to

Afraid of Formalism, states that by “detaching form from the superficial rela- Free Kwinter from Whitehead”. http://www.offramp-la.com/

towards-non-relational-los-angeles/

tions in which they become entangled, [forms] enable resonance between figure

and ground.”34 Where Lynn claims that characteristics of pliancy and suppleness 11 Reference to FAT’s use of the term ‘figural section’ in AD Radical

Postmodernism guest edited by Charles Jencks, Sean Griffiths,

can accommodate, or in fact be formed by, external relations in the production Charles Holland, Sam Jacob

of form, Harman advocates that by detaching form from these externalities new

12 Bob Somol, “What’s Next?” Lecture at University of Kentucky

relationships can be established between the architectural object and its ground, College of Design. 2011

or what we might consider, with some liberties, as context.

13 Le Corbusier, « Introduction » to Towards a New Architecture.

With a goal towards identifying possible post-digital formal qualities, we in fact Dover Architecture, 1985

find many of the principles of ambivalent form in the aggregation spheres, cones, 14 Anthony Vidler, “Losing Face” in The Architectural Uncanny:

Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Boston, MIT Press, 1994. 87

and cylinders. For example, a-frontality, moments of being not spherical but

15 Ibid, 87

Beyond Relationism Four Acts: Between Legibility and Ambivalence 124

nearly so, and elevations that “are not the same as the corners found in rectilin-

ear forms because they usually do not define the hard boundaries common to

architectural elevations.”35 However, also present are qualities of legible form,

such as graphic shapes, figural profiles, and exterior articulation via interiority,

often the illusion of concavity in this case. We can infer from above that ground

is not elided, rather is itself a non-relational resonator with form and figure.

Therefore, an attempt to identify the qualities of synthesis between legibility and

ambivalence reveals:

1) Distributed legibility (visual oscillation of recognition of parts with ambiv-

alent wholes)

2) Contextual de-concealing (reveals something of ground as a figure)

3) Concavity (cleavages and clefts) as exterior articulation resultant from

interior

4) Orientation without frontality

5) Figural profiles with elevational ambivalence

These are not stated as design principles or points to be followed for a contem-

porary architecture. They are not manifesto. Rather they arise from, and call

attention to, possible combinations of legibility and ambivalence as a way of

dovetailing form-making strategies in a post-digital era with emerging disciplin-

ary discourse that elevates the status of form and object.

ACT 4: THE BELVEDERE

It will be useful here to apply these terms. A Belvedere offers a unique typology

for experimentation in which, traditionally, a belvedere is an architectural feature

or building constructed for the purposes of looking out over a pleasing scene.

Provided such simple programmatic responsibility, emphasis can concentrate on

the formal qualities yet have some spatially occupiable constraint. Our Belvedere

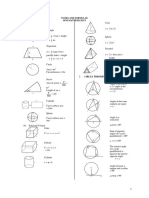

Figure 1: Spheres, Cones, & Cylinders models

125 The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center

appropriates an abandoned missile silo in southern Wyoming. In the context of

this post-military landscape, it rises proximate to 199 other missile silo sites dat-

ing from the Cold War national defense and deterrence network. Rather than

acting to uphold this network or contextualize it, the Belvedere de-networks and

de-infrastructuralizes the 200 sites from their relational status as architecture-

infrastructure. 36 It atomizes the network, emphasizing and elevating the status

of the architectural object while limiting external contingencies. The Belvedere

is a construct whose presence signals neutralization of an otherwise unsettling,

though ultimately covert militarized ground and facilitates new orientations to

the pastoral scene. The Belvedere, composed of only spheres, cones, and cylin-

ders, seems almost alien in relation to context, a monumental object in a field; a

tired trope.

Yet, it is precisely the condition of familiar strangeness that allows everything

around it to be experienced differently; de-concealed, de-networked, de-infra-

structuralized, and de-familiarized. Thus, the figure of the Belvedere acquires

resonance with ground without having been formed or ‘entangled’ with or by

consequences of relational contextualization or responsible to the expanded

field of networked relations or abstracted concepts. Architectural form therefore

becomes a point of interruption that de-relationalizes the territorial network.

The Belvedere sits atop the buried cylindrical silo, extending it vertically with four

intersecting cones of equal base diameters to that of the existing silo, topped by

a crown composed from 11 spheres, 20 cones, and eight cylinders. These recog-

nizable spherical, conical, and cylindrical parts come into and out of focus within

the overall mass, both alleviating and frustrating recognizability with a visual

oscillation between legible parts and ambivalent wholes. 3

The Belvedere aggregates 10 small spheres (1/50th the size of Newton’s

Cenotaph) connected to an eleventh crowning sphere with cylinders and cones.

By nature of aggregating 10 spheres with cones and cylinders, the Belvedere does Figure 2: Large scale Belvedere plaster model

Figure 3: Belvedere in situ

Beyond Relationism Four Acts: Between Legibility and Ambivalence 126

4

not have a frontal face, yet it is graphic with figural profiles composed by aggre-

gated volumes, and is therefore characterized by multiple figural profiles with

elevational ambivalence in a similar way to Payne’s disco balls.

Each of the 10 spheres are cut horizontally in half, forming domes. The vertical

locations of each of the 10 domes are located in such a way as to neither overlap,

nor appear as autonomous, therefore aggregating into one figural-mass. Four

of these directly connect to the four cones of the tower base, providing access

and structure. This provides the Belvedere with a specific, singular orientation

Figure 4: Belvedere Section in the z-dimension yet lacks frontality or facial expression. The formal synthesis

Figure 5: Belveder sphere, cone, & cylinder of aggregated and intersecting parts produces clefts and cleavages as exterior

composition

127 The Expanding Periphery and the Migrating Center

16 Ibid, 89

expressions and articulations derived from functionality and interior use, recall-

ing Rowe’s and Simmel’s claim for an exterior articulation of interiority, as well as 17 Ibid, 88

Corbusier’s attention to mass as the main perceptual and experiential element. 18 Ibid, 92

19 Ibid, 94

INTERMISSION

20 Jason Payne, “Variations on the Disco Ball, or The Ambivalent

Perhaps in combining the qualities and intellectualization of the conceptual and Object” in Project Journal, issue 2. Consolidated Urbanism

aesthetic distance between legibility and ambivalence, post-digital formalism Incorporated, 2013. 20-27

may call attention to modes of research and practice that go beyond relationism. 21 Ibid, 21-25

This allows for a kind of stealth mode, or cunning of disciplinary and contextual

22 Jason Payne, “Doppelganger” http://www.offramp-la.com/

exchange through an emphasis on disciplinary discourse and form-making sen- doppelganger/

sibilities alleviated from the past two decades of networks, systems, and con-

23 Greg Lynn, Intricacy Exhibition introduction at the Institute of

nectivity which aims to renew the status of architectural form from within the Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania. 2003

discipline. Yet, it seems necessary to note that these discussions and usefulness

24 Curated by Phillip Johnson and Mark Wigley, MOMA. 1988

to architecture are still in the early stages…they require more work, debate, and

experimentation; new acts. Key problems present themselves to architects, such 25 This reference is in relation to Greg Lynn’s text, Intricacy in

which Lynn outlines four main themes: Assemblages and

as issues pertaining to ground / context, as difficulties in light of the previous two Aggregation, Voluptuous Surfaces and Undulating Lattices, Vital

or three decades of concentration. Nevertheless, the aim is to refocus attention Mechanism, and Fused Forms.

onto architectural form and the qualities of architectural objects in a post-digital 26 This references Jacques Derrida philosophical and literary

era with the technologies and discussions of today. Through this, perhaps new analysis in his 1967 Of Grammatology, which was adopted

into architecture with an core belief in the destabilization of

acts of architecture will take the stage; ones that eschew the transference of net- essential or intrinsic meaning and thus relinquishing claims for

based concepts to the aesthetics of the discipline of architecture. absolute truth.

27 This makes reference to Viktor Shklovsky’s 1917 essay “Art

as Device” which claims “the purpose of art is to impart the

sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are

known. The technique of art is to make things unfamiliar, and to

increase the difficulty and length of perception…”

28 project description excerpt from http://oma.eu/projects/1989/

zeeburgee-sea-terminal. Found in “City of Spheres” Project

Journal, Issue 1 by Emmanuel Petit

29 The idea of worthy constraints and working firstly within the

discipline, rather than an extroverted or common experience is

in reference to Clement Greenberg’s 1935 text, Avant Garde and

Kitsch.

30 Daniel Sherer, “The Architectural Project and the Historical

Project: Tensions, Analogies, Discontinuities” in LOG31 New

Ancients, Anycorp 2014. 121

31 Ibid, 123

32 Ibid, 123

33 Greg Lynn, “Architectural Curvilinearity: The Folded, the Plian,

and the Supple” in Architectural Design: Folding in Architecture.

1995 & 2004 (revised edition)

34 Graham Harman, “Towards A Non-Relational Los Angeles; Or

How to Free Kwinter from Whitehead”. http://www.offramp-la.

com/towards-non-relational-los-angeles/

35 Jason Payne, “Variations on the Disco Ball, or The Ambivalent

Object” in Project Journal, issue 2. Consolidated Urbanism

Incroprated, 2013. 20-27

36 This is referenced to Anthony Vidler’s, Architecture’s Expanded

Field as an architecture – architecture but within an architec-

ture-landscape. The terms of use are altered to pertain to the

de-networking of an infrastructural condition, thus atomizing

the network of sites into resonant grounds with foreign-like

figures.

Beyond Relationism Four Acts: Between Legibility and Ambivalence 128

You might also like

- Digital Culture and Architecture by Antoine PiconDocument2 pagesDigital Culture and Architecture by Antoine Picondudi0% (2)

- Moussavi Kubo Function of Ornament1Document7 pagesMoussavi Kubo Function of Ornament1Daitsu NagasakiNo ratings yet

- The Function of FormDocument30 pagesThe Function of FormAlan Kawahara100% (1)

- Prim Maths 2 2ed TR Workbook AnswersDocument21 pagesPrim Maths 2 2ed TR Workbook Answers7a4374 his100% (3)

- The Impossible Project of Public Space PDFDocument10 pagesThe Impossible Project of Public Space PDFRîștei AlexandraNo ratings yet

- MATHS SOLID GEOMETRY EXAMDocument6 pagesMATHS SOLID GEOMETRY EXAMHomer Batalao100% (1)

- Airport parking fee and cookie/box shipping calculatorDocument9 pagesAirport parking fee and cookie/box shipping calculatorjscansinoNo ratings yet

- Folding in Architecture PDFDocument40 pagesFolding in Architecture PDFGowtham Namachivayan100% (1)

- Materializing The Digital: Architecture As Interface: Materia Arquitectura #13Document5 pagesMaterializing The Digital: Architecture As Interface: Materia Arquitectura #13Patrícia Helena Turola TakamatsuNo ratings yet

- Patterns, Fabrics, Prototypes, TessellationsDocument10 pagesPatterns, Fabrics, Prototypes, TessellationsDaniel NorellNo ratings yet

- Towards Congruent ArchitectureDocument5 pagesTowards Congruent ArchitectureL r vNo ratings yet

- The Climate of Spaces On Architecture, Atmospheres and TimeDocument10 pagesThe Climate of Spaces On Architecture, Atmospheres and TimeOceanNo ratings yet

- Lynn - Intro Folding in ArchitectureDocument7 pagesLynn - Intro Folding in ArchitectureFrancisca P. Quezada MórtolaNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Knowledge and Practical WisdomDocument8 pagesInterdisciplinary Knowledge and Practical WisdomOrangejoeNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Theory for ArchitectureDocument9 pagesAesthetic Theory for Architectureshumispace319No ratings yet

- Another Form: From The Informational' To The Infrastructural' CityDocument18 pagesAnother Form: From The Informational' To The Infrastructural' CityStephen ReadNo ratings yet

- Participatory Design Through A Cultural Lens: Insights From Postcolonial TheoryDocument4 pagesParticipatory Design Through A Cultural Lens: Insights From Postcolonial TheoryJuan Pablo DueñasNo ratings yet

- For Whom Exploring Landscape Design As A Political ProjectDocument5 pagesFor Whom Exploring Landscape Design As A Political ProjectWowkieNo ratings yet

- Amin CohendetDocument17 pagesAmin CohendetAlexandru Ionuţ PohonţuNo ratings yet

- Cyber-Space: Theoretical Approaches and Considerations: June 2002Document27 pagesCyber-Space: Theoretical Approaches and Considerations: June 2002Giovanna Graziosi CasimiroNo ratings yet

- Johannadrucker Remarks Gettydah-Lab 2013Document6 pagesJohannadrucker Remarks Gettydah-Lab 2013YUENo ratings yet

- Spatial Infrastructure: Essays on Architectural Thinking as a Form of KnowledgeFrom EverandSpatial Infrastructure: Essays on Architectural Thinking as a Form of KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- Barlas - Caliskan - METU JFA.2006 PDFDocument20 pagesBarlas - Caliskan - METU JFA.2006 PDFOlgu CaliskanNo ratings yet

- 2003 - Najle, Ciro - ConvolutednessDocument18 pages2003 - Najle, Ciro - ConvolutednessLuis FernandoNo ratings yet

- ADS5: Ambiguous Architecture - Royal College of ArtDocument8 pagesADS5: Ambiguous Architecture - Royal College of ArtFrancisco PereiraNo ratings yet

- Cuthbert 2007Document47 pagesCuthbert 2007Jana PiNo ratings yet

- Caadria2008 53 Session5b 437.contentDocument8 pagesCaadria2008 53 Session5b 437.contentMudassar AhmadNo ratings yet

- Sustainability: Urban Architecture As Connective-Collective Intelligence. Which Spaces of Interaction?Document16 pagesSustainability: Urban Architecture As Connective-Collective Intelligence. Which Spaces of Interaction?Sewasew KinnieNo ratings yet

- Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press Journal of The Society of Architectural HistoriansDocument4 pagesSociety of Architectural Historians, University of California Press Journal of The Society of Architectural HistoriansEyup OzkanNo ratings yet

- Cuthbert 2007# - Urban Design... Last 50 YearsDocument47 pagesCuthbert 2007# - Urban Design... Last 50 YearsNeil SimpsonNo ratings yet

- Digital Eco Art Transformative PossibilitiesDocument14 pagesDigital Eco Art Transformative PossibilitiesMosor VladNo ratings yet

- Introduction. Performance ArchitectureDocument3 pagesIntroduction. Performance ArchitectureMk YurttasNo ratings yet

- A Social Dimension To Digital Architectural PracticeDocument14 pagesA Social Dimension To Digital Architectural PracticeArwa ZannadNo ratings yet

- ARCHITECTURAL DISJUNCTIONS. Morphological Identity and Syntactic Contrasts of Visibility and PermeabilityDocument18 pagesARCHITECTURAL DISJUNCTIONS. Morphological Identity and Syntactic Contrasts of Visibility and PermeabilityĐurđica StanojkovićNo ratings yet

- Graphesis: Visual Knowledge Production and Representation: Johanna DruckerDocument36 pagesGraphesis: Visual Knowledge Production and Representation: Johanna DruckerRafael EfremNo ratings yet

- Transmediale - De-Across and Beyond Post-Digital Practices Concepts and InstitutionsDocument12 pagesTransmediale - De-Across and Beyond Post-Digital Practices Concepts and InstitutionsmmrduljasNo ratings yet

- Dovey & Scott - Architecture and FreedomDocument9 pagesDovey & Scott - Architecture and FreedomfaetisNo ratings yet

- Beyond Analytical Knowledge: The Need For A Combined Theory of Generation and ExplanationDocument22 pagesBeyond Analytical Knowledge: The Need For A Combined Theory of Generation and ExplanationNuran SaliuNo ratings yet

- City of The FutureDocument30 pagesCity of The FutureJaydeep VaghelaNo ratings yet

- Design is a Communication MediumDocument3 pagesDesign is a Communication MediumsamarNo ratings yet

- Visualizing Design History: An Analytical ApproachDocument19 pagesVisualizing Design History: An Analytical ApproachmonicaandinoNo ratings yet

- Why Architectural Criticism MattersDocument7 pagesWhy Architectural Criticism MattersJoebert DuranNo ratings yet

- What Ever Is Happening To Urban Planning and Urban Design? Musings On The Current Gap Between Theory and PracticeDocument9 pagesWhat Ever Is Happening To Urban Planning and Urban Design? Musings On The Current Gap Between Theory and Practicenasibeh tabriziNo ratings yet

- Architectural Research QuarterlyDocument9 pagesArchitectural Research Quarterlytxnm2015No ratings yet

- A_New_Perspective_on_Eclectic_Attributes_in_ArchitDocument21 pagesA_New_Perspective_on_Eclectic_Attributes_in_ArchitSara ShahinNo ratings yet

- Geo Logics PDFDocument117 pagesGeo Logics PDFmrbookshopNo ratings yet

- In Defense of ParametricismDocument8 pagesIn Defense of ParametricismTimut RalucaNo ratings yet

- Heynen - HHintern - Space As Receptor, Instrument or Stage Interaction Between Spatial and Social ConstellationsDocument18 pagesHeynen - HHintern - Space As Receptor, Instrument or Stage Interaction Between Spatial and Social ConstellationsHumanidades DigitalesNo ratings yet

- The Digital Restructuring of Urban Space: Syllabus: Spring 2017 DRAFTDocument16 pagesThe Digital Restructuring of Urban Space: Syllabus: Spring 2017 DRAFTChristina GrammatikopoulouNo ratings yet

- Remoreras - Research On Module 1Document14 pagesRemoreras - Research On Module 1Christian RemorerasNo ratings yet

- Carmona2013 PDFDocument37 pagesCarmona2013 PDFArkadipta BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Fusion: Kostas Grigoriadis, Guan Lee, Lizy HuygheDocument15 pagesFusion: Kostas Grigoriadis, Guan Lee, Lizy HuygheValeriaNo ratings yet

- Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla: Radical Urban Structures Past and FutureDocument6 pagesGodzilla vs. Mechagodzilla: Radical Urban Structures Past and FuturehamidNo ratings yet

- University of California PressDocument21 pagesUniversity of California Pressceren yılmazNo ratings yet

- Critical regionalism as a strategy for place-based architectureDocument7 pagesCritical regionalism as a strategy for place-based architectureBilal YousafNo ratings yet

- Cubitt Practice of Light PrefacepreproofDocument21 pagesCubitt Practice of Light PrefacepreproofNatanael ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Design Process As Complex System: R. Barelkowski, Int. J. of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics. Vol. 13, No. 1 (2018) 46 59Document14 pagesDesign Process As Complex System: R. Barelkowski, Int. J. of Design & Nature and Ecodynamics. Vol. 13, No. 1 (2018) 46 59pwzNo ratings yet

- Digital Ecosystem: The Journey of A MetaphorDocument40 pagesDigital Ecosystem: The Journey of A MetaphorMaría Isabel Villa MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Acarter - Review #3 PaperDocument23 pagesAcarter - Review #3 PaperAthena CarterNo ratings yet

- Blauvelt Andrew - Towards Relatinal Design - ArtículoDocument4 pagesBlauvelt Andrew - Towards Relatinal Design - ArtículofaneronNo ratings yet

- Architecture and Visual Narrative: ProceedingsDocument12 pagesArchitecture and Visual Narrative: ProceedingsOrçun Cavit AlpNo ratings yet

- The New Politics of Visibility: Spaces, Actors, Practices and Technologies in The VisibleFrom EverandThe New Politics of Visibility: Spaces, Actors, Practices and Technologies in The VisibleAndrea Mubi BrighentiNo ratings yet

- Water Dosing Calculation BookDocument12 pagesWater Dosing Calculation BookSugumar Panneer SelvamNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Introductory Chemistry 5th Edition Tro Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Introductory Chemistry 5th Edition Tro Test Bank PDFmiascite.minion.84dvnz100% (13)

- Math Syllabus F3-F5Document78 pagesMath Syllabus F3-F5Hubert MoforNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Buckling and Ultimate Strength of Spherical Pressure Hull Under External PressureDocument14 pagesAn Overview of Buckling and Ultimate Strength of Spherical Pressure Hull Under External PressureYoyok SetyoNo ratings yet

- 103-Analytical Geometry - 2D and 3D (PDFDrive)Document890 pages103-Analytical Geometry - 2D and 3D (PDFDrive)Tanvir Ahmed100% (1)

- Programming C Mid TermDocument4 pagesProgramming C Mid TermlindaNo ratings yet

- 1 Earth and Its CoordinatesDocument15 pages1 Earth and Its CoordinatesLauda Lessen100% (1)

- Trigonometry Concepts and Reference AnglesDocument5 pagesTrigonometry Concepts and Reference AnglesKim Ryan PomarNo ratings yet

- Notes and Formulae MathematicsDocument9 pagesNotes and Formulae MathematicsNG VictorNo ratings yet

- Physical and Ethereal SpacesDocument39 pagesPhysical and Ethereal Spacesklocek100% (8)

- GravitationDocument25 pagesGravitationPreeti Jain100% (2)

- Electrostatics: (Physics)Document6 pagesElectrostatics: (Physics)Piyush GuptaNo ratings yet

- Surface Area and Volumes Key Concepts: CuboidDocument10 pagesSurface Area and Volumes Key Concepts: CuboidHoney ChunduruNo ratings yet

- Quiz 2: ObjectivesDocument12 pagesQuiz 2: ObjectivesChristian M. MortelNo ratings yet

- 3.1 Plane and Solid Geometry SolutionsDocument10 pages3.1 Plane and Solid Geometry SolutionsReyno D. Paca-anasNo ratings yet

- The Froebel's School: Name: - Class: - DateDocument1 pageThe Froebel's School: Name: - Class: - DateSabih SiddiqiNo ratings yet

- Bus Tracking System and Ticket Generation Using QR Technology PDFDocument5 pagesBus Tracking System and Ticket Generation Using QR Technology PDFResearch Journal of Engineering Technology and Medical Sciences (RJETM)No ratings yet

- Quantum MagazineDocument60 pagesQuantum MagazineEdney MeloNo ratings yet

- Math Formula Cheat SheetsDocument11 pagesMath Formula Cheat SheetsbrunerteachNo ratings yet

- Measuring Rolling Friction Characteristics of A Spherical Shape On A Flat Horizontal PlaneDocument9 pagesMeasuring Rolling Friction Characteristics of A Spherical Shape On A Flat Horizontal PlaneالGINIRAL FREE FIRENo ratings yet

- RATIO-PROPORTIONDocument6 pagesRATIO-PROPORTIONSoundarya SvsNo ratings yet

- List of Moments of Inertia: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia 2Document3 pagesList of Moments of Inertia: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia 2Agniswar Frost MandalNo ratings yet

- DPP 2 18TH April 2020Document10 pagesDPP 2 18TH April 2020gauravNo ratings yet

- Electric Potential Difference Between Charged Concentric Metallic ShellsDocument4 pagesElectric Potential Difference Between Charged Concentric Metallic ShellsHector TrianaNo ratings yet

- BSc Physics GravitationDocument33 pagesBSc Physics GravitationSwapnil PoteNo ratings yet

- Problem Set 4 Solutions: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Physics 8.02 Spring 2013Document14 pagesProblem Set 4 Solutions: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Department of Physics 8.02 Spring 2013Michelle HuangNo ratings yet

- Clayoo - Documentation enDocument117 pagesClayoo - Documentation enCesar Mario DiazNo ratings yet