Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TaghinezhadAbdollahzadehDastpakRezaei PDF

Uploaded by

Yavuz KaradağOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TaghinezhadAbdollahzadehDastpakRezaei PDF

Uploaded by

Yavuz KaradağCopyright:

Available Formats

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

INVESTIGATING THE IMPACT OF GENDER ON

FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNING ANXIETY OF

IRANIAN EFL LEARNERS

Ali Taghinezhad

Department of English Language, Fasa University of Medical Sciences, Fasa, Iran

(Corresponding author email: taghinezhad1@gmail.com)

Pegah Abdollahzadeh

Department of English Language, Shiraz Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shiraz, Iran

Mehdi Dastpak

Department of English Language, Jahrom University of Medical Sciences, Jahrom, Iran

Zohreh Rezaei

Department General of Fars Province Education, Fars, Iran

ABSTRACT

THIS STUDY AIMED AT INVESTIGATING THE IMPACT OF GENDER ON FOREIGN LANGUAGE

LEARNING ANXIETY. TO THIS END, A QUESTIONNAIRE NAMED FOREIGN LANGUAGE

CLASSROOM ANXIETY SCALE WAS ADMINISTERED TO STUDENTS. IN TOTAL, 305

STUDENTS OF JAHROM, KAZERUN, AND SHIRAZ UNIVERSITIES PARTICIPATED IN THIS

STUDY, 74 MALE STUDENTS AND 231 FEMALE STUDENTS RANGING FROM 18 TO 30 YEARS

OF AGE. THE DATA WERE ANALYZED USING STATISTICAL PACKAGE FOR THE SOCIAL

SCIENCES (SPSS) VERSION 19. STANDARD MULTIPLE REGRESSION ANALYSIS WAS

CONDUCTED TO INVESTIGATE WHETHER STUDENTS' GENDER CAN PREDICT THEIR

FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNING ANXIETY. THE RESULTS SHOWED THAT THERE WAS NO

STATISTICALLY SIGNIFICANT DIFFERENCE BETWEEN MALES AND FEMALES REGARDING

FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNING ANXIETY. THEREFORE, GENDER COULD NOT PREDICT

FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNING ANXIETY. THE IMPLICATIONS ARE DISCUSSED AT THE

END OF THE STUDY.

KEYWORDS: GENDER, FOREIGN LANGUAGE ANXIETY, ANXIETY SCALE

1. Introduction

Since foreign language learning is a stressful activity (Hewitt & Stefenson, 2011), many researchers

have investigated the role of anxiety in learning a foreign language (e.g., Phillips, 1992). Foreign

language anxiety has been defined as negative emotional reaction that is caused when using or

learning a foreign or a second language (MacIntyre, 1999). Several studies have been carried out on

language anxiety. Although few of them have revealed that there is a positive relationship between

language anxiety and language achievement (e.g., Liu, 2006; Oxford, 1999), most of them have shown

that language anxiety and language achievement are negatively related (e.g. Horwitz, 2001,

MacIntyre, 1999, MacIntyre, Noels, Clement, 1997). Put it another way, learners who are more

proficient in a foreign language, experience less anxiety in learning it in comparison with other

learners who are not that proficient. Foreign language learning anxiety is a great barrier to foreign

language achievement (Young, 1991), so the low achievement of learners can be attributed to negative

effects of anxiety (Horwitz, 2000, 2001; MacIntyre, 1999, 2002; Tóth, 2007).

1.1 The role of gender

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 418

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

Gender has been considered as a significant factor in SLA. There are some discrepancies between men

and women with regard to second language learning which cannot be fully erased through education.

According to gender theory proposed by Baumeister and Sommer (1997), gender stereotypes are the

expectations which are shared culturally for gender appropriate behaviors. Individuals learn the

appropriate behaviors from the culture and the family they grow up with. Therefore, non-physical

gender differences are the result of socialization (Eagly, 1987). Also, males and females differ

biologically with regard to their learning style and cognitive ability. These differences result from

their differences in their brain and their higher-order cortical functions (Keefe, 1982). In terms of

lateralization, there are differences between males and females, with males having more left-

hemisphere dominance than females (Banich, 1997). Research studies have shown that gender

differences affect students’ academic interest, needs, and achievements (Halpern, 1986).

Anxiety, as an important affective factor, influences second language learning particularly speaking

skill. Males and females have different levels of anxiety and it might delay the development of their

speaking ability. Therefore, learners have to make use of some learning strategies to overcome this

problem. Oxford (1990) maintains that learning strategies are the specific actions which are taken by

the learners to make learning easier, faster, more effective, more enjoyable, and more transferable to

new situations (p. 8). Language teachers try to find the main sources of students’ language learning

anxiety in order that they organize their class in a way which minimizes their students’ anxiety.

Gender is one of the factors that affect the anxiety in second language learning particularly second

language speaking skill.

1.2 Causes of foreign language anxiety

Although all aspects of using and learning a foreign language can cause anxiety, listening and

speaking are regularly cited as the most anxiety provoking of foreign language activities (MacIntyre

and Gardner, 1994; Horwitz, Horwitz & Hope, 1986).

The causes of foreign language anxiety have been broadly separated into three main components:

communication apprehension, test anxiety and fear of negative evaluation. Communication

apprehension is the anxiety experienced when speaking to or listening to other individuals. Test-

anxiety is a form of performance anxiety associated with the fear of doing badly, or indeed faili ng

altogether. Fear of negative evaluation is the anxiety associated with the learner's perception of how

other onlookers (instructors, classmates or others) may negatively view their language ability.

Sparks and Ganschow (1991) asked a question which drew attention to the fact that anxiety could

either be a cause of poor language learning or a result of poor language learning. If a student is

unable to study as required before writing a language examination, the student could experience test

anxiety. In this context anxiety could be viewed as a result. In contrast, anxiety becomes a cause of

poor language learning when due to anxiety that student is unable to adequately learn the target

language. There can be various physical causes of anxiety (such as hormone levels) but the

underlying causes of excessive anxiety whilst learning are fear and a lack of confidence. Lack of

confidence itself can come from various causes. One reason can be the teaching approach used.

1.3 Effects of foreign language anxiety

The effects of foreign language anxiety are particularly evident in the foreign language classroom,

and anxiety is a strong indicator of academic performance. Anxiety is found to have a detrimental

effect on students' confidence, self-esteem and level of participation (MacIntyre & Garnder, 1994).

Anxious learners suffer from mental blocks during spontaneous speaking activities, lack confidence,

are less able to self-edit and identify language errors, and are more likely to employ avoidance

strategies such as skipping class (Gregerson, 2003). Anxious students also forget previously learned

material, volunteer answers less frequently and tend to be more passive in classroom activities than

their less anxious counterparts (Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope, 1986). The effects of foreign language

anxiety also extend outside the second language classroom. A high level of foreign language anxiety

may also correspond with communication apprehension, causing individuals to be quieter and less

willing to communicate (Liu & Jackson, 2008). People who exhibit this kind of communication

reticence can also sometimes be perceived as less trustworthy, less competent, less socially and

physically attractive, tenser, less composed and less dominant than their less reticent counterparts. This

study attempts to answer the following question:

Can foreign language learning anxiety be predicted by students’ gender?

2. Literature Review

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 419

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

Over the past decades, several researchers have investigated the relationship between language

learning anxiety and beliefs about language learning (e.g. Horwitz, Horwitz & Cope, 1986; Lan, 2010;

Wang, 2005; Young, 1991). Studies have shown that most language learners experience anxiety in the

process of language learning (e.g. Andrade & William, 2009; Marwan, 2007). Having realized the

existence of foreign language anxiety in the process of language learning, researchers have

endeavored to decrease its harmful effects. For instance, Young (1991) suggested that learners’ beliefs

about language learning can contribute to foreign language learning anxiety.

In another study, Wang (2005) found that students who had a higher aptitude in language learning

tended to have a lower level of language learning anxiety. Also, Lan (2010) in her study found that

there was a significant negative correlation between language learning beliefs and foreign language

learning anxiety.

In the Iranian context, Toghraee and Shahrokhi (2014) conducted a similar study and found a positive

and statistically significant correlation between Iranian university students’ beliefs about language

learning and their level of language learning anxiety.

2.1 Anxiety in Second Language Acquisition

In second language research, anxiety is considered as an affective variable (Dörnyei, 2005; Horwitz et

al, 1986). Anxiety is composed of some parts which have different features (Dörnyei, 2005).

According to Dörnyei (2005), there are different categorizations for anxiety. Two of the most popular

classifications of anxiety are debilitating-facilitating (Scovel, 1978) and state-trait (Speilberger, 1983)

views of anxiety. In the former dichotomy, the facilitating or beneficial anxiety does not hinder

performance but it can facilitate it whereas debilitating anxiety can deter performance when an

individual is under excessive worry. In the latter classification, trait anxiety is rather stable with the

passage of time, whereas state anxiety is a transitory and changing feeling (Dörnyei, 2005).

Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) identified three types of foreign language anxiety: test anxiety,

communication apprehension, and fear of negative evaluation. In order to measure foreign language

classroom anxiety, they developed a 33-item questionnaire. Several studies have been done on

language anxiety most of which have shown a negative relationship between language learning

anxiety and language achievement (e.g., Horwitz, 2001; MacIntyre, 1999;; MacIntyre, Noels, Clement,

1997) and only a few of them have shown that language achievement is positively related to language

learning anxiety (e.g., Liu, 2006a; Oxford, 1999). Put it another way, the more proficient the learners,

the less anxious they become.

According to Dornyei (2005), trait anxiety is related to an individual’s anxiety in different situations.

He maintains that this is because of the disposition of the individual. MacIntyre (1999) believes that

situation-specific anxiety is similar to trait anxiety for both of them refer to the possibility of being

anxious in a specific situation. For example, language learners might have situation-specific anxiety

when a teacher calls them to speak English in the classroom. Another kind of anxiety is state anxiety

which is the emotional reaction to the present situation and is considered as a moment-to-moment

experience (MacIntyre, 1999; Dornyei, 2005). MacIntyre (1999) differentiates situation-specific anxiety

and trait anxiety from state anxiety. Situation-specific anxiety and trait anxiety refer to the possibility

of getting anxious in a specific situation, while state anxiety refers to the way an individual

experiences anxiety. MacIntryre (1999) suggests that state anxiety has impacts on cognition, emotions,

and behavior. An example for state anxiety can be a person who tries to abandon a situation and the

bodily effects including a rapid heartbeat and a seating palm. This might result when making a

speech in front of a large number of people. Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) maintained that

language anxiety is an identifiable variable in foreign language learning. Krashen (1988) discussed the

influence of affective filter in second language acquisition with regard to input. He suggested that

when the affective filter is high, an individual is less likely to process the input. The affective filter

involves emotional reactions like language anxiety.

Many studies have been done investigating the relationship between anxiety and language learning

indicating that anxiety can have an adverse effect on the performance of those who speak English as a

foreign language (e.g., Chen & Lee, 2011, Stroud & Wee, 2006). Some studies related to the scope of

the present study are reported here. In a study by Liu (2006b), it was revealed that students who had

advanced English language proficiency had less anxiety. In a recent study, Chakrabarti and Sengupta

(2012) studied the language learning anxiety of Indian students. They found that the students’ test

anxiety was high among other components of anxiety.

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 420

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

Rezazadeh and Tavakoli (2009) conducted a study in Iran investigating the relationship among

academic achievement, gender, years of study, and levels of test anxiety. One hundred and ten

Iranian EFL students participated in that study. The findings showed that the female students had a

higher level of anxiety. And there was no relationship between years of study and test anxiety. In

another study by Sadighi, Sahragard and Jafari (2009) on eighty Iranian EFL learners, it was found

that there was no statistically significant relationship between years of study and the level of anxiety.

In a recent study by Mesri (2012a), it was shown that there was a statistically significant relationship

between gender and Foreign Language Class Anxiety (FLCA). According to these studies, language

learning anxiety of EFL learners was on a high range. However, since the number of participants in

the Iranian context is low (n=52), more research on this issue should be done.

2.2 Gender and Second Language Acquisition

Gender has been considered as a significant factor in SLA. Males and females are biologically

different in terms of their mental abilities and their learning styles. These differences arise from the

development of brain and also from higher order cortical functions (Keefe, 1982). Regarding

lateralization, males are more left brain dominant than females (Banich, 1997). Research shows that

gender differences affect students’ needs, academic interests, and achievements. SLA theorists believe

that females have superiority in their L2 process (Ehrlich, 2001).

As Jiménéz-Catalán (2000) states, individual differences such as learning style, age, motivation,

aptitude, learning style and motivation are well discussed in many SLA research studies. However,

little attention has been paid to gender in the field of second language learning and teaching (Catalan,

2003; Nyikos, 2008; Sunderland, 1994). In addition, as Ehrlich (1997) and Sunderland (2000) mention

in their studies, in research studies on gender and SLA, the role of gender is discussed in an

oversimplified manner.

2.3 Studies on Gender in Second Language Acquisition

Ellis (2008) in his scholarly work The Study of Second Language Acquisition has allocated just a few

pages on gender and second language acquisition. First, he explained the distinction between gender

and sex. Then, he mentioned some studies conducted on this issue. Two of the studies belong to

Burstall (1975) and Boyle (1987) showing that female students outperform their male counterparts in

the examinations applied. However, Ellis does not reach any conclusive results regarding these

findings. He maintains that such generalizations may be misleading as Boyle’s study showed that

male students had a higher achievement in listening tests and the findings of Bacon and Finnemann

(1992) indicated that there was no significant difference between females and males. Ellis discusses

learning strategies and attitudes towards learning which are directly related to gender. Regarding the

attitude, he refers to some studies which are related to motivational orientations. For instance,

Ludwig (1983) found that male students were more instrumentally motivated than females, and

based on a study done by Gardner and Lambert (1983), female students of French were more

motivated than males. According to Ellis (2008), there was no unanimity in research studies regarding

gender differences in SLA in terms of attitudes, achievement, and strategy use at that time. Therefore,

he concludes that sex interacts with other variables in determining second language proficiency. So, it

is not always the case that female students perform better than males.

In another study, Coates (1986) showed that girls acquire language better than boys. However, Xin

(2008) maintained that several factors influence the acquisition of a language among which she lists

the personality of the learners from which motivation is derived. She mentions that the role of gender

in language acquisition has been played down by researchers. Therefore, it is too difficult to perceive

the distinctions between men and women in learning a foreign language. Findings of the study

showed that girls tend to learn English better than boys. The girls gave some explanations for their

tendency to learn English. They said that they learn English to acquire knowledge, improve their

communicative ability, and to improve their social status. On the other hand, just a small number of

boys acknowledged that English is important for them. The analysis revealed that girls are more

motivated than boys in learning English as a foreign language.

2.4 Gender and Language Learning Anxiety

Some studies have been done regarding the relationship between gender and language learning

anxiety. Chang (1997) concluded that females had higher level of anxiety than males. In another

study, Ezzi (2012) investigated the relationship between FL anxiety and gender among male and

female students with regard to their educational level, age and residence and found that females had

a higher level of anxiety than males.

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 421

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

In the Iranian context, Rezazadeh and Tavakoli (2009) investigated the relationship between gender

and language learning anxiety and found that females have a higher level of test anxiety in

comparison with their male counterparts. In another study in Iran, Mesri (2012a) arrived at the same

conclusion. However, Fariadian, Azizifar and Gowhary (2014) investigated the role of gender in

speaking anxiety of EFL Iranian learners and found that boys showed higher levels of language

learning anxiety in comparison with female students.

In another study, Aida (1994) found no statistically significant relationship between language

learning anxiety and gender. Tahernezhad et al. (2014) investigated the degree of anxiety among

Iranian intermediate EFL learners and its relation to their motivation and reached the same result.

3. Method

3.1 Participants

In order to collect the required data, three Iranian universities were selected using cluster sampling.

The universities included Shiraz, Jahrom, and Salman Farsi Universities in Shiraz, Jahrom and

Kazerun, respectively. The participants were female and male students of English language. In total,

305 students participated in this study, 74 male students and 231 female students ranging from 18 to

30 years of age. All of them were native speakers of Persian studying English as a foreign language at

university.

3.2 Instruments

A questionnaire was used in this study namely, Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS)

The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree (1) to Strongly Agree (5). This

questionnaire was designed by Horwitz et al. (1986) consisting of 33 items on a 5-point Likert scale

ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). It aimed at examining students’ anxiety

pertaining to foreign language learning in classroom contexts. One of the reasons for using this scale

was that it has been one of the most comprehensive and valid instruments for measuring students’

anxiety in classroom contexts. Another reason was that it showed favorable reliability coefficients

with the samples of population to which it had been administered (Horwitz, 1991). Nowadays, it is a

frequently used scale which is often shortened or adapted in studies which are concerned with similar

purposes. This scale is a self-report measure which assesses the level of anxiety, as indicated by social

comparisons and negative performance expectancies, psycho-physiological symptoms and avoidance

behaviors.

Nakayama (2007) reported the Cronbach’s alpha of this questionnaire as follows: Future Use Anxiety

(a= .929) and In Class Anxiety (a= .770). The reliability coefficient of the FLCAS in this study was .918.

3.3 Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

First, the students were informed about the objectives of the study. Then, they were given the

instructions regarding how to answer the items of the questionnaire. They were asked to answer

open-ended questions such as gender and academic level as well. They were also assured about the

confidentiality of the information that they were supposed to provide.

Having received the questionnaire from the students, the researchers scored, and entered the data

into a spread sheet in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19. Then, descriptive

statistics were computed and reported. The data underwent some descriptive statistics such as

frequencies, mean, and standard deviation together with correlational analyses. Then, further

inferential analyses were performed to find answers to the research question.

4. Results

Standard multiple regression analysis was conducted to investigate whether students' gender can

predict their foreign language learning anxiety. The results are presented in Table 4.9. As observed in

the table, only 0.1 % of variance is explained by the model (R2 = .001). Hence, gender does not predict

language learning anxiety because no statistically significant relationship was found between gender

and language learning anxiety (B = -.033, t = -.583, Sig = .560). This finding is in contrast to that of

Öztürk and Gürbüz (2012) who found that female students had a higher level of anxiety than their

male counterparts while speaking English in the class. However, it is in line with the finding of

Nahavandi and Mukundan (2013) who investigated the effect of gender on Iranian EFL learners’

anxiety and found that gender did not affect learners’ anxiety significantly.

Table 1. Model Summary for Standard Multiple Regression

Model R R Square Adjusted R Square Std. Error of the Estimate

1 .033a .001 -.002 .47589

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 422

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

a. Predictors: (Constant), Gender

Table 2. ANOVAa Results for Standard Multiple Regression

Model Sum of Squares Df Mean Square F Sig.

Regression .077 1 .077 .340 .560b

1 Residual 68.620 303 .226

Total 68.697 304

a. Dependent Variable: Language Learning Anxiety

b. Predictors: (Constant), Gender

Table 4.11 Coefficientsa for Standard Multiple Regression

Model Unstandardized Coefficients Standardized t Sig.

Coefficients

B Std. Error Beta

(Constant) 2.987 .114 26.252 .000

1

Gender -.037 .063 -.033 -.583 .560

a. Dependent Variable: Language Learning Anxiety

5. Conclusion

Thus far, an overall picture of the study has been presented. Now, it is time to recapitulate briefly on

the research questions and the findings derived from the data. Regarding gender difference in terms

of language learning anxiety, it was found that there was no statistically significant difference

between males and females with respect to their language learning anxiety. Although this finding is

contrast to the findings of previous studies (e.g. Chang, 1997; Felson & Trudeau, 1991) who found that

females had higher levels of language learning anxiety than their male counterparts, it is in line with

that of Aida (1994) and Tahernezhad (2014). Examining these conflicting studies shows that some

other intervening variables may account for such inconsistency. For example, in different studies, in

addition to gender variable which is the major focus of studies, there are some discrepancies in the

type of language the students are acquiring; moreover, the participants come from different cultures.

9. Implications

Findings of this study can be beneficial for teachers and learners as well as educational psychologists.

The findings of this study can prove helpful for teachers to pay more attention to the affective factors

of learners. These findings can also help instructors to predict their learners’ anxiety, beliefs, and

behaviors. Teachers can adjust their teaching plans according to their students’ characteristics to

facilitate their learning.

10. Limitations and suggestions for further research

There were some limitations to this study. Inferences drawn from the results of this study cannot be

generalized to other contexts because of cultural differences. Another limitation was that the sample

was not evenly distributed since there were 74 males and 231 females and this could affect the results

of the study. Therefore, generalizing the findings of this study to other contexts and situations should

be exercised with caution. Since this study was a quantitative one and just made use of

questionnaires, more longitudinal and qualitative studies with in-depth interviews are needed to

understand individual differences in greater detail.

REFERENCES

Andrade, M. & William, K. (2009). Foreign language learning anxiety in Japanese EFL university

classes: Physical, emotion, expressive and verbal reactions. Sophia Junior College Faculty Journal, 29, 1-

24.

Banich, M.T. (1997). Breakdown of executive function and goal-directed behavior. In M.T. Banich

(Eds.), Neuropsychology: The neural bases of mental function (pp. 369-390). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin

Company.

Baumeister, R., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). What do men want? Gender differences and two spheres of

belongingness: comment on Cross & Madson. Psychological Bulletin, 122(1), 38–44.

Boyle, J. (1987). Sex differences in learning vocabulary. Language Learning, 37(2), 273-284.

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 423

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

Burstall, C. (1975). Factors affecting foreign-language learning: A consideration of some research

findings. [Electronic version]. Language Teaching and Linguistics Abstracts, 8, 105-25.

Catalan, R. M. J. (2003). Sex differences in L2 vocabulary learning strategies. International Journal of

Applied Linguistics. 13(1), 54-77.

Chakrabarti, A. & Sengupta, M. (2012). Second language learning anxiety and its effect on

achievement in the language. Language In India, 12(8), 50-78

Chang, J. I. (1997). Contexts of adolescent worries: Impacts of ethnicity, gender, family structure, and

socioeconomic status. Paper presented at the annual meeting of NCFR Fatherhood and Motherhood in a

Diverse and Changing World, Arlington, VA.

Coates, J. (1986). Women, men and language: A sociolinguistic account of sex differences in language.

London & New York: Longman.

Dornyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language

acquisition. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Eagly, A. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ehrlich, S. (2001) Representing rape: language and sexual consent. London: Routledge.

Ezzi, N. A. (2012). The impact of gender on the foreign language anxiety of the Yemeni university

students. International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature. 1(2), 65-75.

Fariadian, E., Azizifar, A. & Gowhary, H. (2014). Gender contribution in anxiety in speaking EFL

among Iranian learners. International Research Journal of Applied and Basic Sciences, 8(11), 2095-2099.

Felson, R. B., & Trudeau, L. (1991). Gender differences in mathematics performance. Social Psychology

Quarterly, 54(2), 113-126.

Gardner, R. & Lambert, W. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning. Rowley, Ma:

Newbury House.

Gregerson, T. (2003). To err is human: A reminder to teachers of language-anxious students. Foreign

Language Annals 36 (1): 25–32.

Halpern, J. Y. (1986). Reasoning about knowledge: An overview. In Halpern, J. Y., editor, Proceedings

of the 1986 conference on theoretical aspects of reasoning about Knowledge, pages 1-18. Morgan Kaufmann

Publishers: San Mateo, CA.

Hewitt, E., & Stephenson, J. (2011). Foreign language anxiety and oral exam performance: A

replication of Phillips’s MLJ study. The Modern Language Journal, 96, 170–189.

Horwitz, E. K. (2000). It ain’t over til it’s over: On foreign language anxiety, first language deficits,

and the confounding of variables. The Modern Language Journal, 84, 256-259.

Horwitz, E. K. (2001). Language anxiety and achievement. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21,

112-126.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern

Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132.

Jiménez-Catalán, R. (2000). Sex/Gender: The forgotten factor in SLA textbooks. Proceedings of XXIII

AEDEAN Conference, 2000. Retrieved from

http://www.unirioja.es/universidad/presentacion/pdf_99_00/FModernas9900.pdf

Keefe, J. W. (1982). Assessing student learning styles: An overview. In Keefe, J, W. (Ed) Student

learning styles and brain behavior. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Lan, Y. J. (2010). A study of Taiwanese 7 graders’ foreign language anxiety, beliefs about language learning

and its relationship with their achievement. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Ming Chuan University.

Liu, M. (2006a). Anxiety in EFL classrooms: Causes and consequences. TESL Reporter, 39, 13–32.

Liu, M. (2006b). Anxiety in Chinese EFL students at different proficiency levels, System, 34(3), 301-316.

Liu, M.; Jackson, J. (2008). An exploration of Chinese EFL learners’ unwillingness to communicate and

foreign language anxiety. The Modern Language Journal 92 (1): 71–86

Ludwig, J. (1983). Attitudes and expectations: A profile of female and male students of college French,

German, and Spanish. The Modern Language Journal, 67(2), 216-227.

MacIntyre, P. D. (1999). Language anxiety: a review of literature for language teachers. In D. J. Young

(Ed.), Affect in foreign language and second language learning. New York: McGraw Hill Companies, 24-43

MacIntyre, P. D. (2002). Motivation, anxiety and emotion in second language acquisition. In P.

Robinson (Ed.), Individual differences and instructed language learning. Amsterdam: John Benjamins

Publishing Company, 45-68.

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 424

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

MacIntyre, P. D.; Gardner, R. C. (1994). The subtle effects of language anxiety on cognitive processing

in the second language. Language Learning 44, 283–305.

MacIntyre, P. D., Noels, K. A., & Clement, R. (1997). Biases in self-ratings of second language

achievement: The role of language anxiety. Language Learning, 47, 265-287.

Marwan, A. (2007). Investigating students’ foreign language anxiety. Malaysian Journal of ELT

Research, 3, 37-55.

Mesri, F. (2012a). The relationship between gender and Iranian EFL learners’ foreign language

classroom anxiety (FLCA). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 2(6),

147-156.

Mesri, F. (2012b). Exploring the gender effect on Iranian university learners’ beliefs to learn English.

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 2(6), 98-106.

Nahavandi, N. & Munkundan, J. (2013). Foreign language learning anxiety among Iranian EFL

learners along gender and different proficiency levels. Language in India, 13(1), 133-145.

Nyikos, M. (2008). Gender in language learning. In C. Griffiths (Ed.), Lessons from good language

learners: Insights for teachers and learners (pp.73-82). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. L. (1999). Anxiety and language learner: New insights. In J. Arnold (Ed.), Affect in language

learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 260–278.

Öztürk, G., & Gürbüz, N. (2012). The impact of gender on foreign language speaking anxiety and

motivation. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 654 – 665.

Phillips, E. M. (1992). The effects of language anxiety on students’ oral test performance and attitudes.

The Modern Language Journal, 76, 14–26.

Rezazadeh, M., & Tavakoli, M. (2009). Investigating the relationship among test anxiety, gender,

academic achievement and years of study: A case of Iranian EFL university students. English Language

Teaching, 2(4), 68-74.

Sadighi, F, Sahragard .R, & Jafari, M (2009). Listening comprehension and foreign language classroom

anxiety among Iranian EFL learners. The Iranian EFL Journal, 3,137-52.

Scovel, T. (1978). The effect of affect: A review of the anxiety literature. Language Learning, 28, 129-142.

Sparks, L.; Ganschow, L. (1991). Foreign language learning differences: Affective or native language

aptitude differences? The Modern Language Journal 75 (1), 3–16.

Sunderland, J. (1994). Exploring gender: Questions and implications for English language education. Hemel

Hempstead: Prentice Hall.

Tahernezhad, E., Behjat, F. & Kargar, A. (2014). The relationship between language learning a nxiety

and language learning motivation among Iranian intermediate EFL learners. International Journal of

Language and Linguistics, 2(6-1), 35-48

Toghraee, T. & Shahrokhi, M. (2014). Foreign language classroom anxiety and learners’ and teachers’

beliefs toward FLL: A case study of Iranian undergraduate EFL learners. International Journal of

Applied Linguistics & English Literature, 3(2), 131-137.

Tóth, Z. (2007). Predictors of foreign-language anxiety: Examining the relationship between anxiety

and other individual learner variables. In J. Horváth & M. Nikolov (Eds.), Empirical studies in English

applied linguistics. Pécs: Lingua Franca Csopor, 123-148.

Wang, N. (2005). Beliefs about language learning and foreign language anxiety: A study of university

students learning English as a foreign language in Mainland China. Unpublished M. A. thesis, University

of Victoria.

Young, D. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does language anxiety

research suggest? The Modern Language Journal, 75, 426-439.

Xin, X. (2008). On gender differences in language acquisition. Sino-US English Teaching, 5, 6-10.

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 425

Modern Journal of Language Teaching Methods (MJLTM)

Appendix

Appendix I: Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale

SA A NI D SD

1 I never feel quite sure of myself when I am

speaking in my foreign language class.

2 I don’t worry about making mistakes in

language class.

3 I tremble when I know that I’m going to be

called on in language class.

4 It frightens me when I don’t understand

what the teacher is saying in the foreign

language.

5 It wouldn’t bother me at all to take more

foreign language classes.

6 During language class, I find myself

thinking about things that have nothing to

do with the course.

7 I keep thinking that other students are better

at languages than I am.

8 I am usually at ease during tests in my

language class.

9 I start to panic when I have to speak without

preparation in language class.

10 I worry about the consequences of failing

my foreign language class.

11 I don’t understand why some people get so

upset over foreign language classes.

12 In language class, I can get so nervous when

I forget things I know.

13 It embarrasses me to volunteer answers in

my language class.

14 I would not be nervous speaking in the

foreign language with native speakers.

15 I get upset when I don’t understand what

the

16 Even if I am well prepared for language

class, I feel anxious about it.

17 I often feel like not going to my language

class.

18 I feel confident when I speak in foreign

language class.

19 I am afraid that my language teacher is

ready to correct every mistake I make.

20 I can feel my heart pounding when I’m

going to be called on in language class.

21 The more I study for a language test, the

more confused I get.

22 I don’t feel pressure to prepare very well for

language class.

Vol. 6, Issue 5, August 2016 Page 426

You might also like

- The Effect of Anxiety On Speaking Ability: An Experimental Study On EFL LearnersDocument11 pagesThe Effect of Anxiety On Speaking Ability: An Experimental Study On EFL Learnerslychie26No ratings yet

- Measuring Language Anxiety in An EFL ContextDocument14 pagesMeasuring Language Anxiety in An EFL ContextChoudhary Zahid Javid100% (1)

- EFL Students' Speaking Anxiety: A Case From Tertiary Level StudentsDocument12 pagesEFL Students' Speaking Anxiety: A Case From Tertiary Level Studentssyika izamNo ratings yet

- Anxiety GenderDocument18 pagesAnxiety GenderPaiman OmerNo ratings yet

- The Role of Teachers in ReducingIncreasing Listening Comprehension (Anxiety)Document10 pagesThe Role of Teachers in ReducingIncreasing Listening Comprehension (Anxiety)Juvrianto Chrissunday JakobNo ratings yet

- 02 MarxDocument10 pages02 MarxTeacher ShyneNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Learning Anxiety: The Case of Iranian Kurdish-Persian BilingualsDocument9 pagesForeign Language Learning Anxiety: The Case of Iranian Kurdish-Persian BilingualsPatricia María Guillén CuamatziNo ratings yet

- International Journal of InstructionDocument16 pagesInternational Journal of InstructionWinda HardiyantiNo ratings yet

- Self-Regulated StrategiesDocument14 pagesSelf-Regulated StrategiesOmar KriâaNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of English Language Speaking Anxiety Among Kurdish Undergraduate EFL StudentsDocument11 pagesAn Investigation of English Language Speaking Anxiety Among Kurdish Undergraduate EFL StudentsFaraidoon EnglishNo ratings yet

- Reflections From Teachers and Students On Speaking Anxiety in An EFL ClassroomDocument25 pagesReflections From Teachers and Students On Speaking Anxiety in An EFL ClassroomLina DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Dong Ma ProjectDocument25 pagesDong Ma Projectapi-322712400No ratings yet

- 2nd Chapter Literature Review 4th November 2022Document11 pages2nd Chapter Literature Review 4th November 2022Rehan BalochNo ratings yet

- Causes of Language of AnxietyDocument5 pagesCauses of Language of AnxietyJAN CLYDE MASIANNo ratings yet

- The Interrelatedness of Affective Factors in EFL Learning: An Examination of Motivational Patterns in Relation To Anxiety in ChinaDocument23 pagesThe Interrelatedness of Affective Factors in EFL Learning: An Examination of Motivational Patterns in Relation To Anxiety in ChinaYnt NwNo ratings yet

- ZhangXianping PDFDocument11 pagesZhangXianping PDFemmaniago0829No ratings yet

- Effects of Foreign Language Anxiety and PerceivedDocument12 pagesEffects of Foreign Language Anxiety and PerceivedMacarena AcostaNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH Withb Results and DiscussionsDocument50 pagesRESEARCH Withb Results and DiscussionsLey Anne PaleNo ratings yet

- Measuring Foreign Language Anxiety Among LearnersDocument16 pagesMeasuring Foreign Language Anxiety Among LearnersArben Anthony Quitos SaavedraNo ratings yet

- Students' Perceptions of Language Anxiety in Speaking ClassesDocument19 pagesStudents' Perceptions of Language Anxiety in Speaking ClassesAlejo RamirezNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Anxiety and English Achievement in Taiwanese Undergraduate English-Major StudentDocument14 pagesForeign Language Anxiety and English Achievement in Taiwanese Undergraduate English-Major StudentChelsea Sharon Miranda SiregarNo ratings yet

- P.75!90!10080 The Factors Cause Language Anxiety For ESLDocument16 pagesP.75!90!10080 The Factors Cause Language Anxiety For ESLJessy Urra0% (2)

- The Effects of Educational Level On Learner Anxiety: An Investigation of Iranian LearnersDocument7 pagesThe Effects of Educational Level On Learner Anxiety: An Investigation of Iranian LearnersIJ-ELTSNo ratings yet

- Affect: The Role of Language Anxiety and Other Emotions in Language LearningDocument16 pagesAffect: The Role of Language Anxiety and Other Emotions in Language LearningNgô Thị Cẩm ThùyNo ratings yet

- (15507076 - Heritage Language Journal) Chinese Language Learning Anxiety - A Study of Heritage LearnersDocument26 pages(15507076 - Heritage Language Journal) Chinese Language Learning Anxiety - A Study of Heritage LearnersBienne JaldoNo ratings yet

- Foreign Language Learning Anxiety: The Case of TrilingualsDocument16 pagesForeign Language Learning Anxiety: The Case of Trilingualssamrand aminiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety in English Speaking Courses (#59690) - 50092Document13 pagesThe Role of Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety in English Speaking Courses (#59690) - 50092Eden RempilloNo ratings yet

- Students Level of Anxiety Towards Learning EnglisDocument11 pagesStudents Level of Anxiety Towards Learning EnglisLUISA FERNANDA HERAZO DUVANo ratings yet

- Anxiety 2 PDFDocument10 pagesAnxiety 2 PDFwillianNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Speaking Anxiety in An EFL Classroom PDFDocument25 pagesReflections On Speaking Anxiety in An EFL Classroom PDFRaesa SaveliaNo ratings yet

- Zahra METOPENDocument5 pagesZahra METOPENFidaNo ratings yet

- Speaking Anxiety As A Factor in Studying Efl by Darmaida SariDocument10 pagesSpeaking Anxiety As A Factor in Studying Efl by Darmaida SariAmalin sufiaNo ratings yet

- HELES Journal Fujii (2015)Document18 pagesHELES Journal Fujii (2015)Ảnh MaiNo ratings yet

- Anxiety Effects On EFL Learners When Communicating OrallyDocument20 pagesAnxiety Effects On EFL Learners When Communicating OrallyErikika GómezNo ratings yet

- Anxiety ArticleDocument11 pagesAnxiety Articlevalentina antonia silva galvezNo ratings yet

- Speaking Anxiety in ESL/EFL Classrooms: A Holistic Approach and Practical StudyDocument9 pagesSpeaking Anxiety in ESL/EFL Classrooms: A Holistic Approach and Practical StudyTue Dang100% (2)

- Research EnglishDocument17 pagesResearch EnglishPrincess Mary Grace ParacaleNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in EFL Classrooms: Causes and Consequences: Meihua LiuDocument20 pagesAnxiety in EFL Classrooms: Causes and Consequences: Meihua LiuEmpressMay ThetNo ratings yet

- Investigating ESL University Students' Language Anxiety in The Aural-Oral Communication ClassroomDocument18 pagesInvestigating ESL University Students' Language Anxiety in The Aural-Oral Communication ClassroomCris BarabasNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Anxiety On Iranian Efl Learners Speaking Skill International Research Journal of Applied Basic Science 2014Document8 pagesThe Effect of Anxiety On Iranian Efl Learners Speaking Skill International Research Journal of Applied Basic Science 2014Ajhrina DwiNo ratings yet

- EJ1106656Document14 pagesEJ1106656Researchcenter CLTNo ratings yet

- EJ1183730Document21 pagesEJ1183730Researchcenter CLTNo ratings yet

- The Relationship of Personality Traits With English Speaking Anxiety: A Study On Turkish University StudentsDocument20 pagesThe Relationship of Personality Traits With English Speaking Anxiety: A Study On Turkish University StudentsJamil AhNo ratings yet

- Pananaliksik Kabanata 1 3Document30 pagesPananaliksik Kabanata 1 3John Andrei DavidNo ratings yet

- Language Learning Anxiety Malay Undergra PDFDocument11 pagesLanguage Learning Anxiety Malay Undergra PDFMarisa Puspita DewiNo ratings yet

- Liu - Anxiety 4Document19 pagesLiu - Anxiety 4Danang SaputraNo ratings yet

- A Study On English Language Anxiety LearnersDocument10 pagesA Study On English Language Anxiety LearnersDewi Rosalia AdiebaNo ratings yet

- Anxiety in Oral E ClassroomsDocument19 pagesAnxiety in Oral E ClassroomsSuaad GatusNo ratings yet

- Factors That Cause Anxiety in Learning English Speaking Skills Among College Students in City of Malabon University: Basis For 1 Year Action PlanDocument27 pagesFactors That Cause Anxiety in Learning English Speaking Skills Among College Students in City of Malabon University: Basis For 1 Year Action PlanMarlon OlivoNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Efl Students Self EsteeDocument8 pagesThe Influence of Efl Students Self EsteechioNo ratings yet

- The Role of Gender in Influencing Public Speaking AnxietyDocument12 pagesThe Role of Gender in Influencing Public Speaking AnxietyRahma HasibuanNo ratings yet

- English Anxiety When Speaking EnglishDocument16 pagesEnglish Anxiety When Speaking EnglishHELENANo ratings yet

- Position PaperDocument1 pagePosition PaperloyyssuuNo ratings yet

- An Investigation On HUMSS Students' Public Speaking Anxiety of Using English As A Second LanguageDocument20 pagesAn Investigation On HUMSS Students' Public Speaking Anxiety of Using English As A Second LanguageUniversella Lovegood90% (10)

- Article EnglDocument18 pagesArticle EnglloyyssuuNo ratings yet

- 110-Article Text-221-1-10-20170908Document7 pages110-Article Text-221-1-10-20170908Arta CurriNo ratings yet

- Reading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenFrom EverandReading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Communication in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersFrom EverandEnhancing Communication in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersNo ratings yet

- Crossing Divides: Exploring Translingual Writing Pedagogies and ProgramsFrom EverandCrossing Divides: Exploring Translingual Writing Pedagogies and ProgramsNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageNo ratings yet

- Access To Universal GrammarDocument3 pagesAccess To Universal GrammarYavuz KaradağNo ratings yet

- Lord of The Flies PDFDocument9 pagesLord of The Flies PDFYavuz KaradağNo ratings yet

- An Overview To Approaches and Methods Second Language AcquisitionDocument26 pagesAn Overview To Approaches and Methods Second Language AcquisitionYavuz KaradağNo ratings yet

- In The ClassroomDocument1 pageIn The ClassroomYavuz KaradağNo ratings yet

- The Five Human SensesDocument17 pagesThe Five Human SensesAntonio Gonzalez100% (1)

- G1 - Minutes of The Proposal DefenseDocument4 pagesG1 - Minutes of The Proposal DefensePotri Malika DecampongNo ratings yet

- An Exercise On Cost-Benefits Analysis: Category Details Cost in First YearDocument3 pagesAn Exercise On Cost-Benefits Analysis: Category Details Cost in First YearPragya Singh BaghelNo ratings yet

- Post-Op Instructions For Immediate DenturesDocument1 pagePost-Op Instructions For Immediate DenturesMrunal DoiphodeNo ratings yet

- Multron AVD C500 Series Strobe and EA GD Pages 2 3Document2 pagesMultron AVD C500 Series Strobe and EA GD Pages 2 3tonnyNo ratings yet

- The Subjunctive Mood in Modern Greek: Na +rima Se Enestota)Document3 pagesThe Subjunctive Mood in Modern Greek: Na +rima Se Enestota)Emmanuel BarabbasNo ratings yet

- DPSPS: The Advices of The ConstitutionDocument11 pagesDPSPS: The Advices of The ConstitutionNisha DixitNo ratings yet

- Amino AcidsDocument65 pagesAmino AcidsEmmanuel Chang100% (1)

- An Introduction To Biodegradable Polymers As Implant MaterialsDocument18 pagesAn Introduction To Biodegradable Polymers As Implant Materialsratnav_ratanNo ratings yet

- UtilitiesDocument534 pagesUtilities200211555No ratings yet

- Rfi TrackingDocument42 pagesRfi Trackinganand100% (2)

- Cadbury Operations ProjectDocument28 pagesCadbury Operations Projectparulhrm80% (5)

- 2019 Book DiseasesOfTheChestBreastHeartA PDFDocument237 pages2019 Book DiseasesOfTheChestBreastHeartA PDFAdnan WalidNo ratings yet

- Fluid & Electrolite Management in Surgical WardsDocument97 pagesFluid & Electrolite Management in Surgical WardsBishwanath PrasadNo ratings yet

- Ilovepdf Merged 2 PDFDocument307 pagesIlovepdf Merged 2 PDFAhmed ZidanNo ratings yet

- Discover Biology The Core 6th Edition Singh Test BankDocument16 pagesDiscover Biology The Core 6th Edition Singh Test Bankkylebrownorjxwgecbq100% (16)

- RQ - RP - RPT & FBNDocument35 pagesRQ - RP - RPT & FBNSlim.B100% (2)

- 15 - 16 Lean Management (Final)Document63 pages15 - 16 Lean Management (Final)Aquilando David Mario SimatupangNo ratings yet

- Penicillin ActDocument5 pagesPenicillin Actcecile towerNo ratings yet

- Protein Purification Strategy PDFDocument20 pagesProtein Purification Strategy PDFAmal ShalabiNo ratings yet

- Jewish Standard, February 26, 1016Document56 pagesJewish Standard, February 26, 1016New Jersey Jewish StandardNo ratings yet

- Acei and ArbDocument6 pagesAcei and ArbNurulrezki AtikaNo ratings yet

- Project Name: PTW No.:: Excavation Work PermitDocument1 pageProject Name: PTW No.:: Excavation Work PermitShivendra KumarNo ratings yet

- FL NihongoDocument8 pagesFL NihongoAbigail PantorillaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Sajjad Hussain Sumrra Isomerism (CHEM-305) Inorganic Chemistry-IIDocument48 pagesDr. Sajjad Hussain Sumrra Isomerism (CHEM-305) Inorganic Chemistry-IITanya DilshadNo ratings yet

- Important Monthly Current Affairs Capsule - October 2022Document382 pagesImportant Monthly Current Affairs Capsule - October 2022FebzNo ratings yet

- Letter To MenoeceusDocument3 pagesLetter To MenoeceusmahudNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Batangas State University College of Engineering, Architecture & Fine ArtsDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Batangas State University College of Engineering, Architecture & Fine ArtsDianne VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy and Birth in Denmark - April 2023Document4 pagesPregnancy and Birth in Denmark - April 2023valckefranNo ratings yet

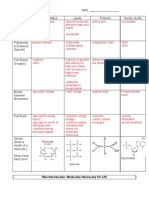

- Macromolecules Worksheet AnswersDocument2 pagesMacromolecules Worksheet AnswersEman RehmanNo ratings yet