Professional Documents

Culture Documents

America's Health Care Problem: An Economic Perspective: Beverly J. Fox Lori L. Taylor

Uploaded by

wiranroOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

America's Health Care Problem: An Economic Perspective: Beverly J. Fox Lori L. Taylor

Uploaded by

wiranroCopyright:

Available Formats

Beverly J. Fox Lori L.

Taylor

Assistant Economist Senior Economist

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

Mine K. Yücel

Senior Economist and Policy Advisor

Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

America’s Health Care Problem:

An Economic Perspective

H ealth care expenditures in the United States

are expanding rapidly. Real per capita expen-

ditures on health care more than doubled over the

in demand, then we should focus on reforming

consumer incentives. If distortions in supply fuel the

expenditures increase, then we should respond

period 1970 –90.1 Real expenditures for health with policies that affect suppliers. If the increase

care are now growing nearly 4 percent per year, in health expenditures reflects shifts in market

while real expenditures on other consumer goods fundamentals—for example, the increasing health

are growing only 2.5 percent per year.2 Further- care demands of an aging population—then

more, health services grew more than twice as fast economic analysis suggests that the system does

as any other major industry during the recent not need fixing, and we should leave it alone.

recession. If expenditures continue to grow at the

current rate, health care will represent a larger Why is everyone so concerned?

share of the United States’ gross domestic product

(GDP) than manufacturing by 2000.3 Until recently, health care costs were not a

The explosive growth in health care expen- major concern of most Americans. Surveys on the

ditures concerns many Americans. Citizens fear top problems facing the United States in 1984 did

that they will be priced out of the market for health not even mention health care.4 Today, however,

care. Business people worry that rising health care reforming the health care system is one of the

costs will reduce the international competitiveness primary objectives of state and federal governments.

of U.S. corporations. Politicians worry that rising A look at health care prices suggests one

bills for health care programs like Medicare and reason for this change in perspective. As Figure 1

Medicaid will force the government to raise taxes

or run increasingly large deficits.

The widespread concern has led to demands

for substantial reform of the U.S. health care

system. Some groups call for controls on health Our thanks to Zsolt Becsi, Steve Brown, and Mark Wynne

care prices. Others want to reform the insurance for their comments and suggestions.

industry. There are plans that call for managed 1

Levit et al. (1991).

competition and plans that eliminate competition

by making the government the sole provider of 2

Based on data from the U.S. Department of Commerce,

health services. There are almost as many plans as Bureau of Economic Analysis.

there are interested parties. 3

Based on data from the U.S. Department of Commerce,

However, before we can fix the system, we Bureau of Economic Analysis.

have to know what parts of it are broken. If the

increase in health expenditures reflects distortions 4

For example, see the reader survey in Tift (1984).

Economic Review — Third Quarter 1993 21

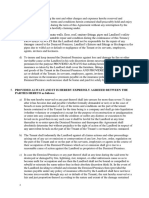

indicates, health care prices increased at roughly Figure 1

the same rate as the general price level until the Consumer Prices

early 1980s. After the mid-1980s, however, the

Index, 1982– 84 = 100

medical care component of the consumer price

index shot upward. By 1992, medical care prices 200

were increasing at more than twice the rate of 180

Medical care

inflation.5

160

This sharp increase in health care prices has

led consumers to fear that they are being priced 140

out of the market for health care. Publicity on the 120

All items

35 million uninsured Americans lends credibility 100

to those fears.6 Because many Americans view

80

health care as essential, the prospect of being

60

unable to afford it frightens them.

Rising health care prices also concern busi- 40

ness because employers pay a large proportion of 20

the Medicare and Medicaid taxes and 64 percent 0

of private insurance premiums.7 Wage and price ’60 ’62 ’64 ’66 ’68 ’70 ’72 ’74 ’76 ’78 ’80 ’82 ’84 ’86 ’88 ’90 ’92

controls during World War II encouraged employers

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

to provide fringe benefits such as health insurance

in lieu of wage increases. The tax-exempt status

of fringe benefits led many employers to continue

the practice after the controls were removed.

Therefore, much of the increase in health care of the federal budget in 1992 and will consume

expenditures is a drag on the balance sheets of 28 percent of the federal budget by 2002.9

American employers. Ultimately, however, consumers bear the

Furthermore, government is concerned about burden of increases in health care spending. Much

increasing health care costs. Federal expenditures of the increase in employer health costs is passed

for Medicare, which finances health care services along to employees in the form of lower wages

for the elderly, and Medicaid, which finances (see the box entitled “Health Care Costs and

health care services for the poor and disabled, Profitability”). The increase in government health

have been growing more than 10 percent per year costs is passed along to citizens in the form of

since 1985.8 The Congressional Budget Office higher taxes or fewer alternative services. There-

estimates that health spending consumed 15 percent fore, consumers would be the primary beneficiaries

of health care reform.

Sources of increasing health

care expenditures

5

The medical care component of the consumer price index It is possible to determine the best way to

may mismeasure medical inflation somewhat, because it is reform the health care system using the basic

difficult to adjust properly for changes in medical tech-

principles of supply and demand. If no distortions

nology and the quality of care. However, it undoubtedly

influences the public’s perceptions of health care prices.

exist, the health care market achieves the optimal

resource allocation for a given income distribution.

6

Garrison (1990). The increase in health care expenditures then

reflects either an increase in the public’s desire for

7

Levit and Cowan (1991).

health services or an increase in legitimate costs.

8

Levit et al. (1991).

Under these conditions, if society is unhappy with

the allocation, the best solution is to redistribute

9

Burman and Rodgers (1992). income without meddling in the health care market.

22 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

Health Care Costs and Profitability

Businesses pay most of the nation’s increases, the total price those firms must pay

health bills, but the effect of increasing health for it decreases, and those firms’ total com-

care costs on profits is not straightforward. pensation costs can fall. Therefore, firms that

Although increases in health costs for retirees offer health insurance as a fringe benefit to

would have a negative effect on firm profitabil- their employees can be made better off—not

ity, increases in health costs for current em- worse off—by the increase in health costs.

ployees can have a positive effect on firm Unfortunately, the savings on total com-

profitability. pensation for current employees can be more

The health care costs of current workers than offset by increased costs for the health

are part of a total compensation offer that is care of retirees. After all, the increases in

determined by the worker’s contribution to the health costs for retirees cannot be offset by

firm’s output. As long as the worker’s produc- decreases in wages. The problem has be-

tivity is unaffected by increases in health care come particularly evident recently as account-

costs, the amount of total compensation the ing rule changes have forced firms to indicate

firm is willing to offer is unaffected by in- their commitments to retiree benefits on their

creases in health costs. Therefore, increases balance sheets. For example, General Mo-

in health costs should be offset by decreases tors was forced to record a $22.2 billion charge

in wages to keep the total compensation in 1992 for retiree and future retiree health

package unchanged. costs.1 Firms that respond to the increase in

Furthermore, the increase in health care health care costs by modifying or eliminating

costs increases the value to employees of the health care coverage for the retired may face

tax exemption for fringe benefits. The advan- increased wage demands by current employ-

tages of being employed by a firm that offers ees who fear being treated in a similar way

health benefits increase, so more workers are when they retire.

attracted to such firms. As the supply of labor

offered to firms that provide health benefits 1

Dallas Morning News (1993).

However, if the health care system is distorted, treatments for health problems, changes in popula-

reform is needed to eliminate the distortions. tion demographics, and society’s reluctance to

We have identified several distortions in the place limits on the value of human life.

current system of health care. First, tax subsidies for

employer-provided health insurance lead to excess The implicit tax subsidy for health insurance

demand for health insurance and, consequently,

to excess consumption of health care. Second, For nearly fifty years, employer-provided

regulations and industry practices restrict the supply fringe benefits have been exempt from both

of health care professionals, leading to higher personal income taxes and payroll taxes such as

prices for health services. Finally, the structure of those for Social Security. Thus, employees avoid

the health insurance industry promotes inefficiency. taxes by taking some of their compensation in the

These distortions of both supply and demand lead form of health insurance. If the combined marginal

to excessive expenditures on health care. tax rate is 28 percent, an employee can receive $1’s

Expenditures also are increasing for several worth of health care instead of 72 cents’ worth of

reasons that are nondistortionary. These reasons after-tax take-home pay (Table 1 ). The difference

include uncertainty about causes and appropriate represents an implied tax subsidy. As Table 1

Economic Review — Third Quarter 1993 23

Table 1

The Subsidized Price of Health Care

Income Effective marginal Price of health care

tax tax rate* in terms of

Wage (percent) (percent) take-home pay

$1 0 14 $.86

$1 15 28 $.72

$1 28 40 $.60

$1 33 45 $.55

*Effective marginal tax rate equals share of the last dollar of monetary compensation paid in

federal taxes and includes both payroll and income taxes.

indicates, those in the highest tax bracket receive sidized and may cause some consumers to be

the largest tax subsidy, while those in the lowest underinsured. Finally, excessive health insurance

tax bracket receive a much smaller subsidy.10 distorts medical research in favor of technologies

Because employees will naturally buy more that extend or improve life at any price rather than

health insurance at 72 cents than at $1, excluding technologies that reduce the costs of treatment.

health-related fringe benefits from taxable income By its nature, health insurance makes con-

increases expenditures on health insurance by sumers less sensitive to health care prices, thereby

those receiving the subsidy. Burman and Rodgers generating more expenditures on health care than

(1992) estimate that the subsidy costs the federal would otherwise occur. Given this relationship,

government $65 billion per year in foregone excessive insurance consumption necessarily leads

revenue and increases private health insurance to excessive health care consumption. Phelps

spending by roughly one-third. (1992) estimates that annual health care expendi-

Excessive consumption of health insurance tures are between 10 percent and 20 percent

has a number of disquieting consequences. First, higher because of the subsidy.

because health insurance leads to increased con- By leading to excessive health care expendi-

sumption of health care, excessive consumption tures, the tax subsidy also can exacerbate the

of health insurance produces excessive consump- problem of the uninsured. Because the subsidy

tion of health care. (For a discussion of the ways increases demand for health care, health care prices

in which health insurance increases health care rise, putting upward pressure on health insurer

consumption, see the box entitled “The Relation- costs. Higher payouts result in higher insurance

ship Between Health Insurance and Health Care premiums. Thus, the subsidy distorts the distribu-

Consumption.”) Second, overconsumption of health tion of health insurance so that higher income

insurance by those receiving the implicit subsidy households overconsume health insurance, while

increases the insurance premiums of the unsub- lower income households can be priced out of

the market for health insurance and health care.

Overconsumption of health insurance also

plays a role in directing technical progress in health

care and has reinforced the development of costly

technologies. Contrary to conventional wisdom,

10

Residents of cities and states with income taxes receive

technological improvements in health care generally

additional subsidies because their fringe benefits are also have not lowered costs. Rather, technological

exempt from local income taxes. innovations have brought about a higher quality

24 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

The Relationship Between Health Insurance and Health Care Consumption

Substantial research indicates that as claims. In such a case, consumers have in-

the price to consumers decreases, health centives to limit their health care consumption

care consumption increases (Long and and submit only those claims that are worth

Rodgers 1990, Phelps 1992, Keeler and Rolph the resulting increase in premiums. In prac-

1988, Manning et al. 1987). According to the tice, however, an individual in a large health

Rand Health Insurance Experiment, the price insurance plan pays an average premium that

elasticity of demand for health care is –0.2 is almost independent of the individual’s risk

(Keeler and Rolph 1988, Manning et al. 1987). or health care consumption. Hence, consum-

In other words, every 1 percent decrease in ers do not bear the full costs of their decisions

consumer prices for health care increases about the extent of claims.

health care consumption by 0.2 percent. Furthermore, the loose connection be-

Insurance reduces the consumer’s ef- tween premiums and claims in health insur-

fective price of health care in two ways. First, ance exacerbates problems of moral hazard.

because health insurers typically pay for health Moral hazard arises when insurance changes

treatments rather than for health losses, in- the insured’s behavior in a way that increases

surance lowers the marginal price of treat- claims. For example, people who are insured

ment. If a consumer is fully insured (and, and who, therefore, know that they will bear

therefore, pays none of the billable costs of only part of the cost of illness, may not be as

treatment), then the marginal cost of health careful of their health as people who are not

care becomes the opportunity cost of the insured. Individuals will have no incentive to

consumer’s time. If a consumer is co-insured, curb unhealthy behavior if increased claims

then the marginal cost of treatment becomes are not reflected in higher premiums, espe-

a predetermined fraction of the treatment cially if behavior cannot be easily monitored.

cost, plus the consumer’s opportunity costs. Thus, health insurance increases ex-

For example, with a copayment of 20 percent, penditures on health care. In the Rand experi-

a $10 prescription antihistamine costs the ment, fully insured individuals spent 30 percent

consumer only $2. In either case, health in- more on outpatient services than individuals

surance effectively reduces the consumer’s with a 25 percent copayment. In turn, individu-

marginal cost of health care. als with a 25 percent copayment spent 28

Second, because health insurance pre- percent more than individuals with a 95 per-

miums are only loosely connected to claims, cent copayment (Manning et al. 1987).1

insurance insulates people from some of the

costs of their decisions. Theoretically, insur-

ance premiums, which reflect expected losses, 1

Both co-insurance programs had an annual cap on out-of-

are a function of health risk and the extent of pocket expenses.

product, which is most often more expensive than rather than the cost-effective technologies that

the older product. Weisbrod (1991) finds that our probably would develop if consumers were more

system of pricing (that is, paying the health care sensitive to health care prices.

provider based on costs incurred or on a fee-for- One could argue that the tax subsidy is

service basis) has led the research and develop- necessary because without it, poor people would

ment sector to develop new technologies that receive less medical care and there would be

enhance the quality of care irrespective of cost greater public health risks from communicable

Economic Review — Third Quarter 1993 25

Figure 2 performing many medical tasks. The restrictions

Average Employer-Provided Health Benefits are ostensibly designed to protect the consumer by

increasing the quality of the health care product.

Dollars

Studies have shown, however, that regulations

3,500 that limit supply do not always lead to higher

quality and tend to increase expenditures because

3,000 Estimated tax subsidy they increase incomes in the profession.

People who want to become doctors must first

2,500

gain entry into an accredited U.S. medical school.

2,000

Doctors who train at nonaccredited schools or in

other countries frequently are not permitted to prac-

1,500 tice medicine in the United States. The market for

medical training is monopolistic, and the number of

1,000 medical school applicants greatly exceeds the number

of openings at accredited schools. Each year since

500

1960, medical school applications have exceeded

0

classroom openings by at least 50 percent (Associa-

$0 to $7,600 to $21,600 to $36,300 to $57,100 tion of American Medical Colleges 1993, Table B–

$7,600 $21,600 $36,300 $57,100 and higher

1). In the 1992–93 school year, there were two

Income quintile applicants for every opening. Restrictions on the

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census.

supply of medical training necessarily restricts the

supply of physicians. Assuming that those students

who were not accepted into medical schools were

only 50 percent as likely to complete their education

diseases such as tuberculosis. However, the pro- as those who were accepted, the restriction reduces

gressive nature of the income tax code negates physician supply by approximately 30 percent.

those arguments. As Figure 2 indicates, high-income Once physicians have graduated from

households receive a greater health insurance medical school, they face additional restrictions

subsidy than low-income households. Households imposed by state and local agencies. States have

that fall in the lowest income tax bracket receive a licensing and regulatory agencies or boards that

small subsidy because health benefits are exempt regulate the medical profession. The agencies

from Social Security and other payroll taxes. Mean- establish the minimum level of education and

while, some of the households in the highest income experience required to practice, define the functions

tax bracket receive a federal subsidy of nearly 50 of the profession, and limit the performance of

percent when both income and payroll taxes are certain functions to licensed professionals. Restric-

considered. In combination with an exemption tions include the use of trade names, restrictions

from state taxes, high-income households in high- on branch offices and location of offices, and, until

tax states receive an even larger subsidy. There is 1977, a ban on advertising (Haas –Wilson 1992).

little risk that high-income households will not be Many studies have shown that occupational

able to afford insurance and no obvious consen- licensing leads to lower consumer welfare and

sus that these groups deserve public assistance. higher incomes in the licensed profession. Economic

theory suggests that self-licensing by the medical

Supply constraints profession leads to economic rents (Friedman

1962 and Stigler 1971). Leland (1979) finds that

Numerous restrictions on entry to the health although minimum quality standards may be

care profession distort health care supply and lead desirable in markets in which suppliers have more

to higher consumer prices. These restrictions information than consumers, the minimum quality

include limits on access to medical training, licens- standards set by the medical industry may be too

ing and certification requirements for doctors, and high. Chan and Leland (1982) show that when both

work rules that exclude paraprofessionals from price and quality are hard to observe, uninformed

26 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

consumers may pay a higher price and receive a Inefficiencies in the insurance

lower quality of goods. Haas –Wilson (1986) finds industry’s structure

that increasing the restrictiveness of optometrists’

licensing examinations increased the price of eye Another distortion in the health care system

exams and eyeglasses significantly but had an arises from the structure of the insurance industry.

insignificant effect on the quality of the eye exams. The market for health insurance is dominated by

Whenever entry into a market is artificially noncompetitive firms. Medicare and Medicaid,

constrained, either through restricted access to which represent 57 percent of the insurance market,

medical training or through obstacles such as are government entities.12 Furthermore, much of

licensing and certification, consumer prices are the private market for health insurance is domi-

inefficiently high. Therefore, restrictions on entry nated by not-for-profit groups like Blue Cross and

into the health care profession, together with Blue Shield. Only 30 percent of the health insur-

work rules that prevent competition within the ance market is served by for-profit commercial

profession between physicians and less-expensive insurers. Without the discipline of competition,

paraprofessionals, increase medical costs. the market for health insurance is inefficient and

Relaxing some of the restrictions on entry encourages higher health care costs.

into the medical profession should make consumers Considerable economic research indicates

better off. Shaked and Sutton (1981) show that that government agencies are, in general, ineffi-

granting monopolistic powers to the self-regulat- cient (Breton 1974, Downs 1967, and Tullock

ing profession is likely to be welfare-reducing and 1965 and 1967). According to Niskanen (1971), gov-

that the entry of paraprofessionals would be ernment agencies are more likely to try to maxi-

welfare-improving. Moreover, the size of the para- mize the size of their budgets than to maximize

profession that leads to the greatest improvement profits because budget size is a mark of the power

in welfare is the size that leads to the greatest and prestige of the agency. Among other bureau-

income loss for members already in the profession. cratic goals are salaries, office perks, and patronage.

Evans and Williamson (1978) estimate that in Weatherby (1971) cites the expansion of personnel

Ontario, Canada, a dental care system that made as a goal pursued by bureaucrats. Borcherding’s

optimal use of paraprofessionals could reduce the (1977) and Spann’s (1977) findings on the growth

cost of care by 30 percent to 40 percent. More of government and lack of productivity growth

recent studies on restrictions in the dental profes- are consistent with Niskanen’s theory. Since agencies

sion (Liang and Ogur 1987) estimate that state have to return any unused moneys to the U.S.

restrictions on the number of auxiliaries a dentist Treasury, they are not residual claimants on cost

can hire and the functions they may perform cost savings in the budget and have few incentives to

consumers $700 million in 1982. cut costs. There is no reason to believe that

Counter to the principles of supply and Medicare and Medicaid administrators behave

demand, there are some who assert that an increase differently than other bureaucrats.

in physician supply would, in fact, cause higher Like government agencies, not-for-profit

prices. They cite the phenomenon that doctors firms also face incentives to behave inefficiently.

charge higher fees in communities with high (Alchian and Demsetz 1972, Eisenstadt and Ken-

physician-to-patient ratios than they charge in nedy 1981, and Sindelar 1988). Nonprofit health

communities that are less well supplied, even insurers have incentives to dissipate any potential

after adjusting for input cost differences. profits through excess payments to doctors and

However, there is no need to suspend the

laws of supply and demand to explain this phe-

nomenon. Where there is a greater density of

physicians, there also may be a greater degree of

specialization and nonprice competition. Physicians

segment a large market and respond to a greater 11

Phelps (1992, 202).

variety of needs and preferences by treating fewer

patients but charging higher prices.11 12

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1992).

Economic Review — Third Quarter 1993 27

hospitals, unusually generous insurance coverage, Nondistortionary sources

or artificially low insurance premiums. Sindelar of increasing expenditures

(1988) finds that, unlike for-profit insurers, Blue

Cross and Blue Shield plans (the Blues) do not In addition to the distortions, a number of

respond to market forces by changing the price of nondistortionary factors lead to higher health care

health insurance (measured as the ratio of pre- expenditures. Uncertainties on the part of both

miums to benefits). In particular, Sindelar finds physicians and consumers as to the nature and

that administrative costs for the Blues increase as causes of health problems lead to more health

the size of the typical insurance claim increases, care consumption than would occur if all informa-

suggesting that the Blues do not take advantage tion were freely available. However, information

of economies of scale that are exploited by com- is not free, and some of these expenditures are the

mercial insurers. natural result of optimization under uncertainty.

In most industries, the existence of a com- Other nondistortionary factors that contribute to

petitive fringe of efficient firms would discipline higher expenditures include changes in the demo-

the inefficient nonprofit firms (Baumol, Panzar and graphic composition of the U.S. population and

Willig 1988; Caves and Christensen 1980). How- the nearly infinite value placed on human lives.

ever, in the insurance industry, inefficient non- Uncertainty has a major influence on medical

profit insurers receive tax advantages not available decision-making. Doctors and patients have in-

to for-profit insurers. Most states tax the insurance complete information about causes and cures for

premiums of for-profit insurers, while they exempt many health problems. Phelps (1992) shows that

the premiums of nonprofit insurers or tax them at there is substantial disagreement and uncertainty

lower rates. Eisenstadt and Kennedy (1981) find within the medical profession about the marginal

that Blue Shield plans were less efficient in states productivity of alternative medical treatments.

where the plans had a tax advantage than in Uncertainty about the optimal course of action for

states where they did not.13 According to Eisen- various health problems, together with consumers’

stadt and Kennedy, “the regulatory advantages distaste for taking risks with their health, leads to

given to the ‘blues’...allow inefficient behavior to increased testing and treatments and, therefore,

be maintained.” 14 higher health expenditures.

One could argue that nonprofit insurers Further, because patients lack the informa-

should receive tax advantages because they gener- tion to reliably judge medical care quality, they

ally accept customers with preexisting conditions must rely on their doctor’s advice and judgment.

that other insurers consider uninsurable. However, But much like an auto mechanic, the doctor has

society could subsidize insurance for individuals incentives to provide (and bill for) more services

with preexisting conditions without requiring that than absolutely necessary and to provide those

the insurer be a nonprofit organization. For ex- services with less than maximum effort. Economists

ample, the government could provide Medicare refer to these situations as principal – agent prob-

and Medicaid recipients with the resources to lems. The usual solution to such problems is a

purchase private insurance rather than providing contract that provides the agent (in this case the

the insurance itself. There is no need to finance health professional) with incentives to behave

an inefficient market structure. optimally and a mechanism for monitoring the

agent’s compliance with that contract. The mecha-

nism to monitor doctors’ behavior and provide

incentives for optimal performance is the mal-

practice suit.

Unfortunately, asymmetric damages make

malpractice suits more effective at inducing careful

13

Inefficiency is measured by the ratio of administrative costs

care than cost-effective care. After all, if the doctor

to premiums. Both administrative costs and premiums are

expressed as net of premium taxes, if any.

orders too few tests and a patient is injured or

killed, the potential damage is huge. However, if

14

Eisenstadt and Kennedy (1981, 27). the doctor orders too many tests, the damage is

28 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

limited to the cost of the tests. Whenever there is Figure 3

uncertainty about the appropriate number of tests, Per Capita Health Care Expenditures by Age, 1987

the risk-averse doctor will prescribe more tests. Thus,

Dollars

malpractice laws and asymmetric damages create

incentives for defensive medicine—procedures 10,000

designed to ward off lawsuits rather than diseases. 9,000

According to the American Medical Association,

8,000

defensive medicine and malpractice insurance add

$36 billion to the nation’s medical bills each year. 15 7,000

In addition to uncertainty, the changing 6,000

demographics of the U.S. population also contrib- 5,000

ute to increases in health care expenditures. Per

4,000

capita health care expenditures increase with both

3,000

age and income. For example, consumers 65 and

over consume more than three-and-one-half times 2,000

as much health care as consumers ages 19 to 64 1,000

(Figure 3). The aging of the population is expected

0

to explain one-seventh of the increase in health Under 19 19 – 64 65 – 84 Over 84

care expenditures over the 40 years from 1990 to Age

2030.16 Furthermore, real U.S. income per capita

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

has grown 2.2 percent per year over the past three

decades, and as populations grow wealthier, they

consume more of all normal goods, including

health care. Simple regression analysis suggests some of the recent increases clearly represent the

that one-quarter of the increase in per capita health demands of an aging and increasingly wealthy

expenditures over the period 1960 – 90 can be population. However, we have identified a number

explained by these two demographic factors. of distortions in the health care market that have

Finally, the high value we place on human a substantial impact on health care expenditures.

life leads to higher expenditures in the health The personal income tax code subsidizes health

care system. Because most consumers would be insurance consumption, thereby fostering exces-

willing to spend huge amounts to avoid dying, sive consumption of health care. Tax exemptions

insured consumers will demand any treatment, for nonprofit insurers and restrictions on the

however costly, that will prolong a patient’s life. supply of health services also lead to higher costs.

The Council of Economic Advisers (1993) esti- To be effective, health care reform must

mates that the 5 percent of beneficiaries who are address these distortions in the health care system.

in the last year of their lives consume 29 percent Eliminating the tax subsidy for employer-provided

of the Medicare budget. health insurance, reducing the tax advantages of

nonprofit insurers, and reducing the restriction

Summary and conclusions on health care providers would go a long way

toward eliminating America’s health care problem.

Health care expenditures in the United States Only after these distortions are removed can the

have expanded rapidly in the past twenty years. economy achieve an efficient allocation of health

This growth in expenditures concerns business resources.

people, politicians, and individual consumers of

health care, although most of the burden falls on

the consumer. Hence, health care reform has

become a primary objective of policymakers.

Increasing expenditures for health care are 15

Felsenthal (1993).

not a problem when they reflect consumer demands

for health care in an undistorted market, and 16

Council of Economic Advisers (1993).

Economic Review — Third Quarter 1993 29

References

Alchian, Armen, and Harold Demsetz (1972), Downs, Anthony (1967), Inside Bureaucracy

“Production, Information Costs and Economic (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co.).

Organizations,” American Economic Review

62 (December): 777– 95. Eisenstadt, David, and Thomas E. Kennedy (1981),

“Control and Behavior of Nonprofit Firms:

Association of American Medical Colleges (1993), The Case of Blue Shield,” Southern Economic

AAMC Databook: Tabulations of Statistical Journal 48 ( July): 26 –36.

Information Related to Medical Education

(Washington, D.C.: AAMC, January). Evans, Robert G., and Malcolm F. Williamson

(1978), Extending Canadian Health Insur-

Baumol, William J., John C. Panzar, and Robert D. ance: Policy Options for Pharmacare and

Willig (1988), Contestable Markets and the Denticare, Ontario Economic Council Re-

Theory of Industry Structure (Fort Worth, search Study no. 13 (Toronto: University of

Texas: Harcourt Brace). Toronto Press).

Borcherding, T.E. (1977), “One Hundred Years of Felsenthal, Edward (1993), “Curing Health Care:

Public Spending,” in Budgets and Bureau- Doctors are Spurring Effort to Remedy the

crats, T.E. Borcherding, ed. (Durham, N.C.: Nation’s Ailing Malpractice System,” Wall

Duke University Press). Street Journal , March 1, B1.

Breton, Albert (1974), The Economic Theory of Friedman, Milton (1962), Capitalism and Freedom

Representative Government (Chicago: Aldine (Chicago: University of Chicago Press).

Publishing Co.).

Garrison, Louis P., Jr. (1990), “Medicaid, the

Burman, Leonard E., and Jack Rodgers (1992), Uninsured, and National Health Spending:

“Tax Preferences and Employment-Based Federal Policy Implications,” Health Care

Health Insurance,” National Tax Journal 65 Financing Review Annual Supplement, 167.

(September): 331– 56.

Haas–Wilson, Deborah (1992), “The Regulation of

Caves, Douglas W., and Laurits R. Christensen Health Care Professionals Other than Physi-

(1980), “The Relative Efficiency of Public and cians,” Regulation: The Cato Review of Busi-

Private Firms in a Competitive Environment: ness and Government, Fall, 40 – 46.

The Case of Canadian Railroads,” Journal of

Political Economy 88 (October): 958 –76. ——— (1986), “The Effect of Commercial Practice

Restrictions: The Case of Optometry,” Journal

Chan, Yuk–Shee, and Hayne Leland (1982), of Law and Economics 29 (April): 165 – 86.

“Prices and Qualities in Markets with Costly

Information,” Review of Economic Statistics 49 Keeler, Emmett B., and John E. Rolph (1988),

(October): 499 – 516. “The Demand for Episodes of Treatment in

the Health Insurance Experiment, Journal of

Council of Economic Advisers (1993), Economic Health Economics 7 (December): 337– 67.

Report of the President (Washington, D.C.:

U.S. Government Printing Office). Leland, Hayne E. (1979), “Quacks, Lemons, and

Licensing: A Theory of Minimum Quality

Dallas Morning News (1993), “GM To Take $22.2 Standards,” Journal of Political Economy 87

Billion Health Charge,” February 2: 1D. (December): 1328 – 46.

30 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

Levit, Katharine R., and Cathy A. Cowan (1991), H.E. Frech III, ed. (San Francisco: Pacific

“Business, Households, and Governments: Research Center for Public Policy).

Health Care Costs, 1990,” Health Care Financ-

ing Review, Winter, 83 – 93. Spann, R.M. (1977), “Rates of Productivity Change

and the Growth of State and Local Govern-

———, Helen C. Lazenby, Cathy A. Cowan, and ment Expenditures,” in Budgets and Bureau-

Suzanne W. Letsch (1991), “National Health crats, T.E. Borcherding, ed. (Durham, N.C.:

Expenditures, 1990,” Health Care Financing Duke University Press).

Review, Fall, 29 – 54.

Stigler, George (1971), “The Theory of Economic

Liang, J. Nellie, and Jonathan D. Ogur (1987), Re- Regulation,” Bell Journal of Economics , Autumn,

strictions on Dental Auxiliaries: An Economic 2 – 31.

Policy Analysis (Washington, D.C.: Federal

Trade Commission, Bureau of Economics, 89). Tift, Susan (1984), “Basking in the Sunshine:

During the Final Heat, a Time Poll Shows a

Long, Stephen H., and Jack Rodgers (1990), “The GOP Romp,” Time, November 5, 21.

Effects of Being Uninsured on Health Care

Service Use: Estimates From the Survey of Tullock, Gordon (1967), Toward a Mathematics

Income and Program Participation,” Congres- of Politics (Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of

sional Budget Office Working Paper no. 9012. Michigan Press).

Manning, Willard G., Joseph P. Newhouse, Naihua ——— (1965), The Politics of Bureaucracy,

Duan, Emmett B. Keller, Arleen Leibowitz, (Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press).

and Susan Marquis, (1987), “Health Insurance

and the Demand for Medical Care,” American U.S. Bureau of the Census (1992), Statistical

Economic Review 77 ( June): 251–77. Abstract of the United States: 1992, 112th ed.

(Washington, D.C.: U.S. Goverment Printing

Niskanen, William A., Jr. (1971), Bureaucracy and Office).

Representative Government (Chicago: Aldine

Publishing Company). Weatherby, J.L. (1971), “A Note on Administrative

Behavior and Public Policy,” Public Choice,

Phelps, Charles E. (1992), Health Economics (New Fall, 107–10.

York: HarperCollins Publishers).

Weisbrod, Burton A. (1991), “The Health Care

Shaked, Avner, and John Sutton (1981), “The Self- Quadrillemma: An Essay on Technological

Regulating Profession,” Review of Economic Change, Insurance, Quality of Care, and Cost

Studies 48 (April): 217– 34. Containment,” Journal of Economic Literature

29 ( June): 523 –52.

Sindelar, Jody L. (1988), “The Declining Price of

Health Insurance,” in Health Care in America,

Economic Review — Third Quarter 1993 31

32 Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas

You might also like

- HealthCareandtheBudget 2Document26 pagesHealthCareandtheBudget 2Committee For a Responsible Federal BudgetNo ratings yet

- Medicare Prescription Drugs: Medical Necessity Meets Fiscal Insanity Cato Briefing Paper No. 91Document12 pagesMedicare Prescription Drugs: Medical Necessity Meets Fiscal Insanity Cato Briefing Paper No. 91Cato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Global HealthDocument3 pagesGlobal HealthAdrian ToledoNo ratings yet

- Appendix To Chapter Four: Applying Supply and Demand Analysis To Health CareDocument6 pagesAppendix To Chapter Four: Applying Supply and Demand Analysis To Health CaredeepikaNo ratings yet

- The Costs of Regulation and Centralization in Health Care by Scott AtlasDocument22 pagesThe Costs of Regulation and Centralization in Health Care by Scott AtlasHoover InstitutionNo ratings yet

- United States Healthcare - Economics (1) KaiDocument7 pagesUnited States Healthcare - Economics (1) KainichuhegdeNo ratings yet

- A Different Perspective on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care ActFrom EverandA Different Perspective on the Patient Protection and Affordable Care ActNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0140673619308414Document28 pagesPi Is 0140673619308414VitaNo ratings yet

- Lec1 Introduction STDocument37 pagesLec1 Introduction STMiracleTesfayeNo ratings yet

- Health Care Transparency Final PaperDocument19 pagesHealth Care Transparency Final Paperapi-242664158No ratings yet

- Economics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadDocument20 pagesEconomics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadHarriet Mikels100% (20)

- Healthcare Takes Centre Stage, Finally!Document29 pagesHealthcare Takes Centre Stage, Finally!Anjali GuptaNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadDocument20 pagesMacroeconomics 6th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual DownloadDarrell Davis100% (21)

- Crisis of Abundance: Rethinking How We Pay for Health CareFrom EverandCrisis of Abundance: Rethinking How We Pay for Health CareRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- LWV RecentHealthCareChangesDocument4 pagesLWV RecentHealthCareChangesjrfh50No ratings yet

- USHealth11 MarmorDocument6 pagesUSHealth11 Marmorchar2183No ratings yet

- LWV CausesRisingHealthCareCostsDocument2 pagesLWV CausesRisingHealthCareCostsjrfh50No ratings yet

- Health_Disparities_and_Health_Education-1final (1)Document12 pagesHealth_Disparities_and_Health_Education-1final (1)brendahronoh254No ratings yet

- Weekly Economic Commentary 9/30/2013Document4 pagesWeekly Economic Commentary 9/30/2013monarchadvisorygroupNo ratings yet

- Restoring Quality Health Care: A Six-Point Plan for Comprehensive Reform at Lower CostFrom EverandRestoring Quality Health Care: A Six-Point Plan for Comprehensive Reform at Lower CostNo ratings yet

- Policy Evaluation PaperDocument14 pagesPolicy Evaluation Paperapi-534245869No ratings yet

- AT - Benefits Economy (Neg)Document2 pagesAT - Benefits Economy (Neg)rashi patelNo ratings yet

- Mining for Gold In a Barren Land: Pioneer Accountable Care Organization Potential to Redesign the Healthcare Business Model in a Post-Acute SettingFrom EverandMining for Gold In a Barren Land: Pioneer Accountable Care Organization Potential to Redesign the Healthcare Business Model in a Post-Acute SettingNo ratings yet

- Leadership Skills for the New Health Economy a 5Q© ApproachFrom EverandLeadership Skills for the New Health Economy a 5Q© ApproachNo ratings yet

- Witness Testimony Sophia Tripoli HE Hearing 03.28.23Document16 pagesWitness Testimony Sophia Tripoli HE Hearing 03.28.23petersu11No ratings yet

- National Factsheet Final 073109Document2 pagesNational Factsheet Final 073109sech100% (2)

- Principle #5: Continued Vigilance in Health Reform March 31, 2010Document6 pagesPrinciple #5: Continued Vigilance in Health Reform March 31, 2010Committee For a Responsible Federal BudgetNo ratings yet

- life-sciences-and-healthcareDocument12 pageslife-sciences-and-healthcarecnvb alskNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Highs Deductible Healthcare Spending Accounts (Hsas)Document15 pagesRunning Head: Highs Deductible Healthcare Spending Accounts (Hsas)Topher MatthewsNo ratings yet

- Economics 5th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesEconomics 5th Edition Hubbard Solutions Manual 1zacharyricenodmczkyrt100% (20)

- E, E, M F: T D I M C R: Quality Fficiency AND Arket UndamentalsDocument45 pagesE, E, M F: T D I M C R: Quality Fficiency AND Arket UndamentalsafsNo ratings yet

- Averting The Medicare Crisis: Health IRAs, Cato Policy AnalysisDocument8 pagesAverting The Medicare Crisis: Health IRAs, Cato Policy AnalysisCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0140673617310012 Main - PDF - FINDocument2 pages1 s2.0 S0140673617310012 Main - PDF - FINSri R NugrohoNo ratings yet

- Niles Chp1 2021Document22 pagesNiles Chp1 2021Trent HardestyNo ratings yet

- Revitalizing the American Healthcare System: A Comprehensive Guide to Rebuilding, Reforming, and Reinventing Healthcare in the United States: Transforming the Future of Healthcare in America: A Practical and Inclusive ApproachFrom EverandRevitalizing the American Healthcare System: A Comprehensive Guide to Rebuilding, Reforming, and Reinventing Healthcare in the United States: Transforming the Future of Healthcare in America: A Practical and Inclusive ApproachNo ratings yet

- Bending The HC CurveDocument18 pagesBending The HC CurveRoy TannerNo ratings yet

- Final Information Effect 1Document7 pagesFinal Information Effect 1api-403222634No ratings yet

- Dollars and SenseDocument2 pagesDollars and SensesevensixtwoNo ratings yet

- HB 109 7Document12 pagesHB 109 7420No ratings yet

- Running Head: Health Care Cost EconomicsDocument7 pagesRunning Head: Health Care Cost EconomicsAlexandria SparksNo ratings yet

- Why Health Economics is an Important and Interesting FieldDocument25 pagesWhy Health Economics is an Important and Interesting Fieldstallioncode5009No ratings yet

- Controversy in U.S Healthcare System PolicyDocument5 pagesControversy in U.S Healthcare System Policydenis edembaNo ratings yet

- Health Care Delivery System MPAN 642: Elizabeth Nunez Touro College PA Program NUMC Class of 2021 12/06/2020Document16 pagesHealth Care Delivery System MPAN 642: Elizabeth Nunez Touro College PA Program NUMC Class of 2021 12/06/2020Elly NuñezNo ratings yet

- Aff Round 4 BlocksDocument5 pagesAff Round 4 BlocksDaniela JovelNo ratings yet

- Research Final Draft-Hannah ColtraneDocument10 pagesResearch Final Draft-Hannah Coltraneapi-609650254No ratings yet

- 2004-07-17 The Health of Nations - The Economist - Tome 1Document8 pages2004-07-17 The Health of Nations - The Economist - Tome 1Guillaume ZhangNo ratings yet

- Healthy, Wealthy, and Wise: 5 Steps to a Better Health Care System, Second EditionFrom EverandHealthy, Wealthy, and Wise: 5 Steps to a Better Health Care System, Second EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- QUESTION # 1: Analyze Why Is It Important For Health Care Managers and Policy-Makers To Understand The Intricacies of The Health Care Delivery SystemDocument5 pagesQUESTION # 1: Analyze Why Is It Important For Health Care Managers and Policy-Makers To Understand The Intricacies of The Health Care Delivery SystemLenie ManayamNo ratings yet

- Case Study 1Document22 pagesCase Study 1kuarNo ratings yet

- Hca 451 Economic Analysis PaperDocument13 pagesHca 451 Economic Analysis Paperapi-535414037No ratings yet

- The Fiscal Challenges Facing Medicare: Entitlement Spending and MedicareDocument20 pagesThe Fiscal Challenges Facing Medicare: Entitlement Spending and MedicarelosangelesNo ratings yet

- Medical Coding and Compliance NIHDocument18 pagesMedical Coding and Compliance NIHBrandi TadlockNo ratings yet

- 2015 Health Care Providers Outlook: United StatesDocument5 pages2015 Health Care Providers Outlook: United StatesEmma Hinchliffe100% (1)

- Prevention in Health Care ReformDocument16 pagesPrevention in Health Care ReformTim KenneyNo ratings yet

- Rose The US Economic Healthcare SystemDocument4 pagesRose The US Economic Healthcare SystemChrisantus OkakaNo ratings yet

- Up 01 Hzpeohch 1 BGDocument27 pagesUp 01 Hzpeohch 1 BGCẩm NhiNo ratings yet

- Basics of HealthCare DomainDocument4 pagesBasics of HealthCare DomainRajivNo ratings yet

- Bcom 241 Risk and Insurance NotesDocument73 pagesBcom 241 Risk and Insurance NotesvictorNo ratings yet

- Pacific Banking Corp. vs. CADocument1 pagePacific Banking Corp. vs. CAJohn Mark RevillaNo ratings yet

- Nahidah Rana 2022Document3 pagesNahidah Rana 2022nahidahcomNo ratings yet

- APA Format: Why Use APA StyleDocument8 pagesAPA Format: Why Use APA Styleimran bazaiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 SolutionsDocument35 pagesChapter 14 SolutionsAnik Kumar MallickNo ratings yet

- How Life Insurance Impacts Poverty in Kwara StateDocument62 pagesHow Life Insurance Impacts Poverty in Kwara StateDaniel ObasiNo ratings yet

- Disaster PreparednessDocument43 pagesDisaster PreparednessskyeNo ratings yet

- Policy D083517387Document2 pagesPolicy D083517387ZishanNo ratings yet

- Impact of customer buying behaviour towards insurance productsDocument26 pagesImpact of customer buying behaviour towards insurance productsMohammad ALi ShaikhNo ratings yet

- How Insurance Drives Economic Growth: June 2018Document18 pagesHow Insurance Drives Economic Growth: June 2018Hamza AbidNo ratings yet

- Statement of Income and Tax Calculation for AY 2020-2021Document2 pagesStatement of Income and Tax Calculation for AY 2020-2021Mohammad AzharuddinNo ratings yet

- White Gold Marine Services, Inc., vs. Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation PDFDocument7 pagesWhite Gold Marine Services, Inc., vs. Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation PDFFatima TumbaliNo ratings yet

- LacayDocument1 pageLacayjm lacayNo ratings yet

- Investment in Bonds Guide - Accounting for Purchases, Sales, Interest IncomeDocument3 pagesInvestment in Bonds Guide - Accounting for Purchases, Sales, Interest IncomejdjdbNo ratings yet

- CH 11 Income On House PropertyDocument11 pagesCH 11 Income On House PropertyJewelNo ratings yet

- Car Rental Agreement ViosDocument6 pagesCar Rental Agreement ViosKathyrn Ang-ZarateNo ratings yet

- Global Health Benefits: Policy Holder: Policy #: Effective Date: Insured: Member #Document1 pageGlobal Health Benefits: Policy Holder: Policy #: Effective Date: Insured: Member #youtube clapzzyNo ratings yet

- Marites Estrella-AGENCY-Shield-PHP-02242023073309Document11 pagesMarites Estrella-AGENCY-Shield-PHP-02242023073309jasleh ann villaflorNo ratings yet

- RFQ R F Q F P C S: Equest OR Uotation OR Rofessional Onsulting ErvicesDocument25 pagesRFQ R F Q F P C S: Equest OR Uotation OR Rofessional Onsulting ErvicesallawicomicsNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Regular Income Tax RatesDocument46 pagesIntroduction to Regular Income Tax RatesBisag AsaNo ratings yet

- VD Nữa NèDocument14 pagesVD Nữa NèviethoangrepNo ratings yet

- Infosys Technologies LimitedDocument3 pagesInfosys Technologies LimitedMahendran ManoharanNo ratings yet

- Case Study 6 - Walnut Venture Associates (D) : RBS Deal Term: Group 2Document5 pagesCase Study 6 - Walnut Venture Associates (D) : RBS Deal Term: Group 2Daniyal AsifNo ratings yet

- Cash Flow & Spending Plan TemplateDocument3 pagesCash Flow & Spending Plan Templatey.a97No ratings yet

- Chapter 2: The Risk Management Function: Lecturer: Amadeus GABRIEL Bba4 La Rochelle Business SchoolDocument45 pagesChapter 2: The Risk Management Function: Lecturer: Amadeus GABRIEL Bba4 La Rochelle Business SchoolJuana BoresNo ratings yet

- Additional Problem Chap 3 SolutionDocument10 pagesAdditional Problem Chap 3 Solutionprincetonu67% (3)

- Financial Performance of Icici Prudential Life Insurance Company and Kotak Mahindra Life Insurance Company: A Comparative StudyDocument5 pagesFinancial Performance of Icici Prudential Life Insurance Company and Kotak Mahindra Life Insurance Company: A Comparative StudygyandeepbhagawatiNo ratings yet

- Traditional Life Insurance ExamDocument10 pagesTraditional Life Insurance ExamOmar sarmientoNo ratings yet

- Rent payment, repairs, insurance obligations in commercial leaseDocument1 pageRent payment, repairs, insurance obligations in commercial leaseThoong Yew ChanNo ratings yet