Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lower Extremity Disorders

Uploaded by

isauraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lower Extremity Disorders

Uploaded by

isauraCopyright:

Available Formats

Article musculoskeletal

Lower Extremity Disorders in Children

and Adolescents

Brian G. Smith, MD*

Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to:

1. Recognize and distinguish congenital clubfoot from metatarsus adductus.

Author Disclosure 2. Understand treatments and approaches to pes planovalgus or flatfoot.

Dr Smith has 3. Describe the natural history of torsional lower extremity deformities in children.

disclosed no financial 4. Discuss the differential diagnosis of idiopathic toe walking in children.

relationships relevant

to this article. This

commentary does not

Clubfoot

Congenital talipes equinovarus or clubfoot is one of the oldest known congenital defor-

contain a discussion

mities, and its diagnosis and treatment date back to the time of Hippocrates.

of an unapproved/ With a personal experience of clubfoot treatment over the past 50 years, Ignacio Ponseti

investigative use of a from the University of Iowa has maintained that careful serial manipulation and casting

commercial product/ followed by a percutaneous heel cord release yields better outcomes than the more

device. extensive posteromedial release performed commonly in the past 2 decades.

Epidemiology

Clubfoot occurs in about 1 in 1,000 live births and is more common in certain races or

ethnic groups. For example, among South Pacific natives, the incidence of clubfoot is 7 per

1,000. Involvement is bilateral in about 50% of patients, and there is a male predominance

of 2:1.

Pathogenesis

The precise pathogenesis of congenital clubfoot remains unclear. This complex disorder

possibly involves genetic, neurologic, muscular, and intrauterine compression influences.

A genetic predisposition exists, but a specific genetic cause has not been identified at this

time.

Physical Findings and Presentation

Clubfoot may be identified by prenatal ultrasonography as early as 12 weeks of gestational

age. Definitive diagnosis is by clinical examination after birth and is characterized by the

four components of clubfoot: equinus positioning, cavus positioning, metatarsus adduc-

tus, and hindfoot varus (Fig. 1).

On physical examination, the foot is resistant to passive correction of the fixed hindfoot

varus and typically maintains a rigid equinus position. The hindfoot involvement separates

clubfoot from metatarsus adductus. Also in the differential diagnosis of this deformity is a

congenital rocker bottom foot and a calcaneovalgus foot, both of which are distinguished

from clubfoot by forefoot abduction. Additional evaluation, including imaging studies,

seldom is necessary prior to initiation of casting.

Treatment

Ponseti’s technique involves serial weekly cast changes to correct forefoot adduction and

hindfoot varus deformities, followed by a percutaneous tendo-achilles lengthening for

most patients. Bracing with the Denis-Browne bar and wearing straight last shoes full-time

for the first few months, then wearing them at night for years, also are critical parts of

treatment. With this approach, open posteromedial release surgery can be limited to fewer

than 10% of patients born with clubfoot. The technique achieves excellent functional

results with minimal morbidity.

*Associate Professor, Department of Orthopaedics, Yale University, New Haven, CT.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009 287

musculoskeletal lower extremity disorders

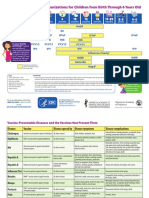

Figure 1. Congenital club foot, demonstrating equinus (A) and cavus positioning (B), metatarsus adductus (C), and hindfoot varus

(D).

Early referral to an orthopedist is recommended, with Epidemiology

treatment ideally starting in the first weeks after birth, The incidence of MTA has been estimated to be approx-

although good results can be attained even at late ages. imately 1 in 1,000 to 1,500 births but may be higher in

Long-term outcomes, based on the work of Ponseti, are infants who have a positive family history. Approximately

very favorable for a plantigrade, functional foot. About 50% to 60% of affected infants have bilateral involvement.

10% to 20% of children may need a second operation to

balance the foot by transferring the anterior tibialis ten-

don at around 4 to 6 years of age. Lack of compliance Pathogenesis

with wearing the bar and shoes as prescribed has been Although the exact cause of MTA remains undefined,

associated with worse outcomes. current theories include muscle imbalance in the foot, a

congenitally abnormal medial cuneiform bone, and sub-

luxation of the tarsal-metatarsal joints. In addition, this

Metatarsus Adductus condition historically was reported to be associated with

Metatarsus adductus (MTA) is a congenital foot defor- hip dysplasia, a component of the “molded baby” syn-

mity characterized by adduction or medial deviation of drome that included the triad of developmental dysplasia

the forefoot relative to the hind foot. Unlike the clubfoot of the hip, MTA, and torticollis. More recent studies

deformity, there is no hind foot varus or equinus defor- have documented no association of MTA with develop-

mity of the foot and ankle. mental dysplasia of the hip. Consequently, screening

288 Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009

musculoskeletal lower extremity disorders

ultrasonography of the hip no longer is necessary in this shoes, casting, and rarely, soft-tissue release of the tight

condition. (1) medial structures.

Clinical Aspects

The typical findings in a patient born with MTA include Prognosis

a convex lateral border of the foot and a medial instep Most patients born with MTA respond well to manipu-

skin crease in addition to the medial deviation of the lation and stretching of the feet. Persistent adduction

forefoot (Fig. 2). Flexibility or rigidity of the deformity deformity in a 4- to 6-month-old should prompt referral

can be assessed clinically by abducting or laterally deviat- to an orthopedist for additional care. Fewer than 5% of

ing the forefoot while holding the hind foot. The severity affected patients have any residual issues over the long

of the adduction can be determined by placing a straight term.

edge in the mid-portion of the heel and determining

where it intersects the forefoot. Normally, the heel bisec-

tor should intersect the second toe or first web space. Flatfoot

Differential diagnosis includes clubfoot, skewfoot Pes planus, or flatfoot, is the typical condition of most

(deviation of the forefoot medially with hind foot val- children’s feet until 6 years of age. Nearly all children

gus), and in older children, cavovarus feet. Diagnosis is flatten the medial longitudinal arch of the foot when

based on clinical findings; imaging studies are not needed bearing weight because of generalized ligamentous lax-

to validate treatment. ity. Once the child’s foot becomes more mature at 6 to 8

years of age, the medial arch maintains elevation on

Treatment standing in most children. Because flatfoot is so common

Therapy directed at stretching the tight medial structures in childhood, a flexible flatfoot may be considered a

of the infant’s foot typically are very effective in correct- normal variant in growing children rather than a patho-

ing this deformity. The technique includes stabilizing the logic condition.

heel with one hand and abducting the forefoot or pulling A small subset of patients have persistent flatfoot that

the great toe in the direction of the little toe. Such may become painful in adolescence. This condition often

manipulation can be performed easily by the parents and is associated with obesity, external tibial torsion, or pos-

is recommended at diaper changes starting in the new- sibly a tight heel cord. As many as 10% to 15% of

born period. Studies suggest that most infants correct American adults have flatfoot.

with manipulation by 4 to 6 months of age if MTA is

diagnosed early and treated.

Usually, no more than 10% to 15% of children require Physical Findings and Presentation

additional treatment, which may include reverse last The key initial assessment of the child presenting with

flatfoot is to determine flexibility. A medial longitudinal

arch collapse during standing can be restored in most

children by recumbency or sitting, and the arch elevates

with toe standing. Passive elevation of the great toe also

raises the arch.

Another physical finding to assess is the presence of

hind foot valgus or lateral position of the heel. Toe

standing causes medial deviation of the heel in normal

feet and is a sign that both the flat arch and heel position

are flexible.

A hindfoot that does not invert with toe standing may

be an indication of some other disorder, such as peroneal

spasm, tarsal coalition, or even inflammatory arthritis of

the subtalar joint. The final important findings to assess

are heel cord excursion and ankle dorsiflexion. Heel cord

tightness may be the reason for hind foot valgus, may

Figure 2. Metatarsus adductus, demonstrating medial devia- cause a painful flatfoot in adolescents, and always should

tion of forefoot and convex lateral border of the foot. be evaluated.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009 289

musculoskeletal lower extremity disorders

Treatment Separating ITW from mild diplegia can be difficult;

Studies have indicated that putting a small arch support gait analysis may be one method. Patients who have ITW

such as a “cookie” or scaphoid pad into the shoe of a without heel cord contractures may be able to walk on

small child does not influence or promote development their heels, whereas those who have diplegia and cerebral

of the arch, which is more related to the genetics or palsy seldom can. Children afflicted with muscle weak-

“destiny” of the child. Thus, for children younger than ness disorders often are very slow runners compared with

age 8 years, treatment rarely is indicated, and reassurance patients who have ITW. Normal blood findings, such as

of expected improvement is all that is necessary for most aldolase and creatine kinase concentrations, and genetic

patients. data suggest a diagnosis of ITW rather than underlying

For the teenager presenting with a painful flatfoot, the muscle disease.

diagnosis of a tight heel cord prompts the recommenda-

tion for a heel cord stretching program, possibly directed

by a physical therapist. Orthotics also may be beneficial. Treatment

If pain persists after these measures, referral to an ortho- Initial treatment of ITW is to ensure that the child’s heel

pedist is recommended. cords remain supple. Stretching exercises of the tendo-

achilles are the first mode of treatment. A few visits with

Idiopathic Toe Walking a physical therapist who can teach the patient and parents

Idiopathic toe walking (ITW) is the persistence of toe- stretching techniques often is helpful.

toe gait beyond age 3 years. Many toddlers experiment Once the child who has ITW is 4 or 5 years of age or

with different walking techniques, but children typically the tendo-achilles is tight, casting may be needed. Cast-

acquire a heel-toe gait pattern by age 4 years. If toe ing produces slight weakness of the gastrocnemius,

walking persists after age 7 to 8 years, a heel cord con- which may help break a habit of toe walking. Nighttime

tracture may prevent spontaneous resolution. bracing with an ankle–foot orthosis may help maintain

Although the natural history of ITW is unknown, heel cord length and prevent recurrence of a contracture.

what seems fairly common in children is rare among Interventions such as botulinum toxin injections or

adults, suggesting that many patients improve or resolve surgery for gastrocnemius or heel cord lengthening

the tendency as their bodies get bigger and heavier. No rarely are needed but may be helpful when the condition

studies document long-term deleterious effects on the is refractory.

feet or ankles of patients whose toe walking persists in The ideal time to refer a patient to an orthopedist

adulthood. is about age 3 or 4 years of age so the ITW may be

improved or minimized by the start of school at age 5

years.

Physical Findings

Initially, patients who have ITW demonstrate no specific

abnormalities on static examination, only on observation Tibial Torsion

when walking. With time, heel cord contracture and calf Tibial torsion is a rotational deviation of the tibia such

hypertrophy develop. Long-term, ITW may cause a com- that the foot is malaligned with the knee. Internal tibial

pensating external tibial torsion and splaying of the fore- torsion is more common than external tibial torsion and

foot, which may not regress with correction of ITW. is an internally rotated position of the child’s foot during

Most important on examination is to assess and deter- ambulation, causing an in-toeing gait pattern.

mine the presence of a tendo-achilles contracture be-

cause this finding affects treatment decisions.

Pathogenesis

Differential Diagnosis Internal tibial torsion is considered to be caused by

Toe walking may be caused by a variety of conditions, intrauterine “packaging.” The left leg is affected more

including cerebral palsy (especially diplegia or hemi- commonly, but involvement frequently is bilateral. Some

plegia), muscle weakness disorders such as Duchenne children may be predisposed to internal tibial torsion,

muscular dystrophy, and even a tethered spinal cord or based on family history. Internal tibial torsion also may

other neurologic conditions. Autism also has been asso- be associated with bowleggedness (infantile tibial vara),

ciated with toe walking, especially the high functioning especially in children who walk early at 8 to 9 months of

subtype or Asperger syndrome. age.

290 Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009

musculoskeletal lower extremity disorders

External tibial torsion may be an acquired rotational

deformity developed as compensation for persistent fem-

oral anteversion. Either type of tibial torsion may present

in a child who has a neuromuscular disorder such as

cerebral palsy or myelodysplasia.

Clinical Aspects

Internal tibial torsion is a common cause of frequent

tripping in a 1- to 3-year-old toddler who has in-toeing.

Tibial torsion is diagnosed by examination in the prone

position, sometimes with the child in the mother’s lap.

The relationship of the foot to the thigh defines the

“thigh-foot angle,” with the normal angle having the

foot rotated 10 to 15 degrees external relative to the long

axis of the thigh. Rotational position of the foot toward

the midline is internal tibial torsion (Fig. 3), and rotation

of the foot beyond 20 degrees external to the thigh is

external tibial torsion.

Typically, radiographs are not needed to assess tibial

torsion, but occasionally computed tomography scans of

the hip, knee, and ankle can be used to document rota-

tion in those patients undergoing surgical correction of

torsional deformities.

Treatment

The natural history of internal tibial torsion is spontane-

ous resolution by the age of 5 or 6 years for most patients.

Other than reassuring the parents, no treatment is

needed. Little science supports the use of braces or bars

and shoes to correct rotational malalignment, despite a

long history of their use. In comparison, external tibial

torsion may persist during growth and, in some cases,

worsen.

Surgery involving derotational distal tibial osteotomy Figure 3. Internal tibial torsion, as demonstrated by foot-

may be needed in patients older than age 6 years if thigh angle. Note the prone position of patient.

significant clinical deformity from either internal or ex-

ternal tibial torsion affects function or gait.

than 20 degrees and retroversion is version less than 10

Prognosis degrees. Increased internal rotation of the hip results

Although most patients who have internal tibial torsion from increased femoral anteversion and may reflect cap-

have a benign course, those who have external tibial sular laxity in addition to anteversion.

torsion may need referral and surgery. As long as patients

remain within 2 standard deviations of the mean, based Pathogenesis

on thigh-foot angle measurements, observation and re- Newborns typically have anteversion of 40 degrees, yet

assurance are all that most need. the typical adult has anteversion of 15 degrees. During

normal growth and development, femoral anteversion

Femoral Anteversion regresses by 25 degrees, or approximately 2 degrees per

Femoral anteversion refers specifically to the angulation year from birth to age 12 years. Femoral anteversion may

or tilt of the femoral neck relative to the shaft of the persist in patients who have abnormal muscle tone, such

femur. The normal version (angulation) of the femoral as spasticity in children who have cerebral palsy, or ex-

neck is 15 degrees. Anteversion refers to inclination more cessive joint laxity.

Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009 291

musculoskeletal lower extremity disorders

Figure 4. Extreme internal rotation of hips associated with

bilateral femoral anteversion.

Clinical Aspects

Any child presenting with in-toeing who is older than 3

or 4 years of age likely has femoral anteversion as the

cause. Physical findings are seen best on prone examina-

tion, where the hip rotation is assessed most easily and

accurately. Increased medial thigh rotation or internal

rotation beyond 60 to 65 degrees is consistent with a

diagnosis of femoral anteversion (Fig. 4), which often is

associated with a decrease in external hip rotation (Fig.

5). Internal rotation of the hip less than 20 degrees may

be considered to be femoral retroversion. Patients who

have femoral retroversion may have associated pes planus

Figure 5. Limited external rotation of hip associated with

and external tibial torsion, as well as being overweight.

femoral anteversion.

Radiographic studies seldom are necessary to docu-

ment femoral anteversion, although computed tomogra-

phy scan, as in tibial torsion, may be useful to the surgeon

ineffective and are not recommended. Normal or mature

for patients undergoing correction. Research has vali-

adult gait is not achieved in most children until age 6 to

dated that a careful physical examination is an accurate

8 years. Thus, maturity often helps in resolving in-toeing.

method of diagnosing femoral anteversion. (2)

Whether W-sitting (Fig. 6) is deleterious or delays natu-

ral remodeling of anteversion is controversial. Some

Treatment

patients who have femoral anteversion and persist in

Anteversion as a cause of in-toeing in children typically

“W” sitting acquire compensatory external tibial torsion,

resolves by age 10 to 12 years. Rarely is surgical treat-

which results in a normal foot progressive angle. How-

ment required. Persistent severe anteversion associated

ever, the torsional forces at the knee may lead to patella

with in-toeing that causes functional impairment may

femoral malalignment and pain, often termed the “mis-

be treated with femoral derotation osteotomy. The need

erable malalignment syndrome.”

for correction occurs more commonly in children who

have cerebral palsy or collagen vascular disorders that

cause persistent anteversion due to abnormal mechanics Prognosis

or joint laxity, respectively. The association of persistent femoral anteversion and hip

Parents concerned about in-toeing caused by femoral arthritis has been sought, but natural history studies have

anteversion in younger children can be reassured that not confirmed any relationship. Patella-femoral arthritis

growth helps with remodeling. Although used in the may be more common in patients who have anteversion

past, bracing, twister cables, and shoe modifications are with acquired external tibial torsion.

292 Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009

musculoskeletal lower extremity disorders

Summary

• Lower extremity disorders of children present

commonly to the pediatric office and are a source of

significant parental anxiety.

• A careful history and physical examination often

yield the diagnosis.

• Most of these disorders require only observation and

reassurance of the parents that the conditions will

improve with time.

• Some disorders, such as clubfoot, need prompt

referral, but most lower extremity disorders can be

monitored by the pediatrician in the office and

resolve with growth.

Suggested Reading

Figure 6. “W” sitting position. Alvarez C, De Vera M, Beauchamp R, et al. Classification of

idiopathic toe walking based on gait analysis. Gait Posture.

2007;26:428 – 435

Dobbs MB, Nunley R, Schoenecker PL. Long-term follow-up of

Recent studies suggest that an in-toeing gait may patients with clubfeet treated with extensive soft tissue release.

be beneficial in certain activities and sports. Therefore, JBJS(A). 2006;88:986 –996

parents may be assured that persistent increased femoral Herzenberg J, Nogueira M. Idiopathic clubfoot. In: Abel M, ed.

anteversion should not compromise athletic perfor- Orthopaedic Knowledge Update: Pediatrics 3. Rosemont, Ill:

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2006:227–235

mance.

Kasser J. The foot. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, eds. Lovell and

The relationship of femoral retroversion to slipped Winters Pediatric Orthopaedics. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lip-

capital femoral epiphysis also has been explored. Al- pincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:1257–1329

though femoral retroversion alone may not predispose to Lincoln T, Suen P. Common rotational variations in children. J Am

slipped capital femoral epiphysis, often affected patients Acad Orthop. 2003;11:312–320

Noonan K. Lower limb and foot disorders. In: Fischgrund J, ed.

have associated factors such as obesity that combine to

Orthopaedic Knowledge Update 9. Rosemont, Ill: American

place them at risk for a slipped epiphysis. Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2008:741–757

Olney B. Conditions of the foot. In: Abel M, ed, Orthopaedic

Knowledge Update: Pediatrics 3. Rosement, Ill: American Acad-

emy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 2006:235–249

References Ponseti IV. Treatment of congenital clubfoot. JBJS(A). 1992;74:

1. Kollmer CE, Betz RR, Clancy M, et al. Relationship of congen- 448 – 454

ital hip and foot deformities. Orthop Trans. 1991;15:96 Schoenecker PL, Rich MM. The lower extremity. In: Morrissy RT,

2. Ruwe PA, Gage JR, Ozonoff MD, DeLuca PA. Clinical deter- Weinstein SL, eds. Lovell and Winters Pediatric Orthopaedics.

mination of femoral anteversion. a comparison with established 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:

techniques. JBJS(A). 1992;74:820 – 830 1157–1213

Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009 293

musculoskeletal lower extremity disorders

PIR Quiz

Quiz also available online at pedsinreview.aappublications.org.

1. A mother brings in her 3-year-old son because she thinks he “walks funny.” On physical examination, you

note that he consistently walks on his toes. Other findings, including those on neurologic examination, are

normal. Which of the following statements about this boy’s condition is true?

A. Bracing of the feet and lower legs should be initiated immediately.

B. He should be tested for muscular dystrophy.

C. He likely will not perform well in sports.

D. Heel cord contracture likely will develop if the toe walking continues.

E. There is a high probability that he has an underlying spinal cord disorder.

2. Which of the following is a characteristic of metatarsus adductus?

A. Hindfoot equinus deformity.

B. Hindfoot varus deformity.

C. Hindfoot valgus deformity.

D. Lateral deviation of the forefoot.

E. Medial crease of the instep.

3. A 7-year-old girl is brought to your clinic for in-toeing that has persisted since she was about 3 years of

age. She frequently sits in a “W” pattern on the floor while watching television. Physical examination

reveals markedly increased internal rotation of the hips while prone. Which of the following statements

regarding this girl’s condition is true?

A. Computed tomography scan is indicated to confirm the diagnosis.

B. She is at high risk for developing osteoarthritis of the hips later in life.

C. She likely will be able to participate in sports without difficulty.

D. She should begin wearing medial pads in her shoes to correct the in-toeing.

E. The in-toeing likely is due to a dietary deficiency.

4. You are evaluating an 18-month-old boy whose mother thinks he is “pigeon-toed.” He began walking at

12 months and walks well, but in-toeing is noted on examination. Range of motion at the hips, knees, and

ankles is normal. Which of the following is the most likely cause of his gait disturbance?

A. Blount disease.

B. Femoral anteversion.

C. Internal tibial torsion.

D. Metatarsus adductus.

E. Pes planus.

294 Pediatrics in Review Vol.30 No.8 August 2009

You might also like

- Hip Disorders in Children: Postgraduate Orthopaedics SeriesFrom EverandHip Disorders in Children: Postgraduate Orthopaedics SeriesRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint: Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandDisorders of the Patellofemoral Joint: Diagnosis and ManagementNo ratings yet

- Congenital Talipes Equinovarus (Clubfoot)Document4 pagesCongenital Talipes Equinovarus (Clubfoot)Julliza Joy PandiNo ratings yet

- Litrev ClubfootDocument6 pagesLitrev Clubfootdedyalkarni08No ratings yet

- 239 1078 4 PBDocument5 pages239 1078 4 PBEmiel AwadNo ratings yet

- Liu 2015Document9 pagesLiu 2015mmm.orthoNo ratings yet

- ClubfootDocument12 pagesClubfootjoycesiosonNo ratings yet

- ClubfootDocument9 pagesClubfootLorebell100% (5)

- Foot Deformities Infant: AssessmentDocument5 pagesFoot Deformities Infant: AssessmentAnup PednekarNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Pes Planus: A State - Of-The-Art Review James B. CarrDocument12 pagesPediatric Pes Planus: A State - Of-The-Art Review James B. CarrTyaAbdurachimNo ratings yet

- High Dislocation of the Hip Treated with Subtrochanter Femoral Shortening Osteotomy Fixed with TBWDocument7 pagesHigh Dislocation of the Hip Treated with Subtrochanter Femoral Shortening Osteotomy Fixed with TBWReza Devianto HambaliNo ratings yet

- Internal RotationDocument15 pagesInternal RotationBrian ChimpmunkNo ratings yet

- Flatfoot Deformity An OverviewDocument9 pagesFlatfoot Deformity An OverviewpetcudanielNo ratings yet

- Ministry of Defence Synopsis of Causation Pes PlanusDocument14 pagesMinistry of Defence Synopsis of Causation Pes PlanusSari HestiyariniNo ratings yet

- Lower Limb Deformity in ChildrenDocument13 pagesLower Limb Deformity in ChildrenShyra RahmnNo ratings yet

- Angkle Fracture in Children 2Document14 pagesAngkle Fracture in Children 2hahaha hacimNo ratings yet

- Refer atDocument9 pagesRefer atMaharani Dhian KusumawatiNo ratings yet

- What's New in Pediatric Orthopaedics: J Bone Joint Surg AmDocument10 pagesWhat's New in Pediatric Orthopaedics: J Bone Joint Surg AmYariel AraujoNo ratings yet

- Club Foot: Ison, Kevin Christian B. BSN3D1Document27 pagesClub Foot: Ison, Kevin Christian B. BSN3D1Saputro AbdiNo ratings yet

- Knock Kneed Children: Knee Alignment Can Be Categorized As Genu Valgum (Knock-Knee), Normal or Genu Varum (Bow Legged)Document4 pagesKnock Kneed Children: Knee Alignment Can Be Categorized As Genu Valgum (Knock-Knee), Normal or Genu Varum (Bow Legged)Anna FaNo ratings yet

- Genu Varo PDFDocument10 pagesGenu Varo PDFazulqaidah95No ratings yet

- Cavus Foot Deformity Evaluation and Surgical TechniquesDocument13 pagesCavus Foot Deformity Evaluation and Surgical TechniquesRadu StoenescuNo ratings yet

- Congenital Abnormalities MusculoSkeletal SystemDocument116 pagesCongenital Abnormalities MusculoSkeletal SystemVii syilsaNo ratings yet

- Osteotomias PediatriaDocument13 pagesOsteotomias PediatriaM Ram CrraNo ratings yet

- ClubfootDocument27 pagesClubfootPrashanth K NairNo ratings yet

- Developmental Dysplasia of HipDocument13 pagesDevelopmental Dysplasia of HipIndra Purwanto AkbarNo ratings yet

- Mayank Pushkar. Congenital Talipes Equinovarus (CTEV) SRJI Vol - 2, Issue - 1, Year - 2013Document7 pagesMayank Pushkar. Congenital Talipes Equinovarus (CTEV) SRJI Vol - 2, Issue - 1, Year - 2013Dr. Krishna N. SharmaNo ratings yet

- deslizamiento epifisiario femur ovidDocument7 pagesdeslizamiento epifisiario femur ovidnathalia_pastasNo ratings yet

- Joshis External Stabilisation System Jess For Recurrent Ctev Due To Irregular Follow Up PDFDocument5 pagesJoshis External Stabilisation System Jess For Recurrent Ctev Due To Irregular Follow Up PDFshankarNo ratings yet

- FlatFoot PDFDocument281 pagesFlatFoot PDFJosé Manuel Pena García100% (1)

- Develop Med Child Neuro - 2009 - ROOT - Surgical Treatment For Hip Pain in The Adult Cerebral Palsy PatientDocument8 pagesDevelop Med Child Neuro - 2009 - ROOT - Surgical Treatment For Hip Pain in The Adult Cerebral Palsy PatientSitthikorn StrikerrNo ratings yet

- Deformity Around KneeDocument94 pagesDeformity Around KneeVarun Vijay100% (3)

- Congenital AbnormalitiesDocument37 pagesCongenital AbnormalitiesrezkadehaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric OrthopaedicDocument66 pagesPediatric OrthopaedicDhito RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Club Foot: 1 Genetics 2 DiagnosisDocument8 pagesClub Foot: 1 Genetics 2 DiagnosispaulNo ratings yet

- CTEV (Congenital Talipes Equinovarus) 2Document6 pagesCTEV (Congenital Talipes Equinovarus) 2Rahmat Syukur ZebuaNo ratings yet

- CTEVDocument46 pagesCTEVjhogie afitnandriNo ratings yet

- Pes Cavus - PhysiopediaDocument10 pagesPes Cavus - PhysiopediavaishnaviNo ratings yet

- Pearls and Tricks in Adolescent Flat FootDocument14 pagesPearls and Tricks in Adolescent Flat FootVijay KumarNo ratings yet

- Congenital Muscular Torticollis and Scapula Elevation LectureDocument102 pagesCongenital Muscular Torticollis and Scapula Elevation LectureFahmi MujahidNo ratings yet

- Genu ValgoDocument9 pagesGenu Valgoazulqaidah95No ratings yet

- Ortopedia Pediatrica en Recien Nacidos JAAOSDocument11 pagesOrtopedia Pediatrica en Recien Nacidos JAAOSjohnsam93No ratings yet

- Arthrogryposis: A Review and UpdateDocument7 pagesArthrogryposis: A Review and UpdateBlajiu BeatriceNo ratings yet

- Multimodality Imaging of The Paediatric FlatfootDocument17 pagesMultimodality Imaging of The Paediatric FlatfootSatrya DitaNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument11 pagesCase StudyAnj TadxNo ratings yet

- Pediatrichipandpelvis: Bertrand W. ParcellsDocument14 pagesPediatrichipandpelvis: Bertrand W. ParcellsMarlin Berliannanda TawayNo ratings yet

- Developmental Dysplasia of The Hip From Birth To Six MonthsDocument11 pagesDevelopmental Dysplasia of The Hip From Birth To Six MonthsRatnaNo ratings yet

- Anomalies of Skeletal System-1Document44 pagesAnomalies of Skeletal System-1Meena KoushalNo ratings yet

- Pediatricflatfoot: Pearls and PitfallsDocument14 pagesPediatricflatfoot: Pearls and PitfallsSuplementos Fit CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Patellar InstabilityDocument16 pagesPatellar InstabilitydrjorgewtorresNo ratings yet

- Williams2014Document10 pagesWilliams2014Eugeni Llorca BordesNo ratings yet

- TC, SB, DDH, CtevDocument23 pagesTC, SB, DDH, CtevMukharradhiNo ratings yet

- Bony Abnormalities in Classic Bladder Exstrophy - The Urologist's PerspectiveDocument11 pagesBony Abnormalities in Classic Bladder Exstrophy - The Urologist's PerspectiveJad DegheiliNo ratings yet

- PFP Syndrome Causes, Risk Factors and ClassificationDocument20 pagesPFP Syndrome Causes, Risk Factors and ClassificationJoãoNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Hip Dislocations in Children and Adolescents: Pitfalls and ComplicationsDocument7 pagesTraumatic Hip Dislocations in Children and Adolescents: Pitfalls and ComplicationsFadhli Aufar KasyfiNo ratings yet

- Ankle and FootDocument31 pagesAnkle and FootmetoNo ratings yet

- Congenial Hip DysplasiaDocument6 pagesCongenial Hip DysplasiaDrew CabigaoNo ratings yet

- Congenital Talipes Equinovarus 222Document10 pagesCongenital Talipes Equinovarus 222jjjj30No ratings yet

- Hallux Varus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandHallux Varus, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Looking Back: Some Reflections on the Prevention and Treatment of Low Back PainFrom EverandLooking Back: Some Reflections on the Prevention and Treatment of Low Back PainNo ratings yet

- Pals BookletDocument12 pagesPals BookletisauraNo ratings yet

- PRN Asthma TXDocument29 pagesPRN Asthma TXisauraNo ratings yet

- Wms GINA 2018 Strategy Report V1.1 PDFDocument161 pagesWms GINA 2018 Strategy Report V1.1 PDFEdson ArmandoNo ratings yet

- Parent Ver SCH 0 6yrs PDFDocument2 pagesParent Ver SCH 0 6yrs PDFrafiullah353No ratings yet

- 2013AminoglycosideDosingGuide PDFDocument2 pages2013AminoglycosideDosingGuide PDFFelipe SotoNo ratings yet

- Dapus PDFDocument49 pagesDapus PDFsyahyuniNo ratings yet

- Visual Diagnosis and Dysmorphology Series: Trisomy 21 Approach and ManagementDocument21 pagesVisual Diagnosis and Dysmorphology Series: Trisomy 21 Approach and ManagementisauraNo ratings yet

- Parent Ver SCH 0 6yrs PDFDocument2 pagesParent Ver SCH 0 6yrs PDFrafiullah353No ratings yet

- ABP New Content Outline PDFDocument14 pagesABP New Content Outline PDFJeremy PorterNo ratings yet

- FIU - Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Clinical EvaluationDocument51 pagesFIU - Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Clinical Evaluationmursyid nasruddinNo ratings yet

- Fractured Thumb 5Document20 pagesFractured Thumb 5Noor Al Zahraa AliNo ratings yet

- Judo, Karate, and TaekwondoDocument14 pagesJudo, Karate, and TaekwondoALFREDO LIBROSNo ratings yet

- Understanding Sports Hernia Athletic PubDocument40 pagesUnderstanding Sports Hernia Athletic PubBichon OttawaNo ratings yet

- Irreducible Fracture-Dislocations of The Femoral Head Without Posterior Wall Acetabular FracturesDocument7 pagesIrreducible Fracture-Dislocations of The Femoral Head Without Posterior Wall Acetabular Fracturesakb601No ratings yet

- Strength and Power Training For All Ages Harvard HealthDocument57 pagesStrength and Power Training For All Ages Harvard HealthJeremiahgibsonNo ratings yet

- Anatomy State Exam1Document12 pagesAnatomy State Exam1Manisanthosh KumarNo ratings yet

- Runner's Knee (IT Band Syndrome) Exercises - Prevention & TreatmentDocument9 pagesRunner's Knee (IT Band Syndrome) Exercises - Prevention & Treatmentd_kourkoutas100% (1)

- MASSAGE THERAPY FOR FACIAL PARALYSISDocument39 pagesMASSAGE THERAPY FOR FACIAL PARALYSISBhargavNo ratings yet

- Osteochondroma of The Mandibular Condyle: About A CaseDocument3 pagesOsteochondroma of The Mandibular Condyle: About A CaseasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Foot phalanges anatomy and growthDocument9 pagesFoot phalanges anatomy and growthAfif MansorNo ratings yet

- Gross Motor DevelopmentDocument42 pagesGross Motor DevelopmentRahma WulanNo ratings yet

- MicrobiologyDocument142 pagesMicrobiologyzakarya alamamiNo ratings yet

- Zach Roys Powerbuilding Program For Men MASTERDocument51 pagesZach Roys Powerbuilding Program For Men MASTERStandaardStanNo ratings yet

- Pex 02 07Document7 pagesPex 02 07Drax The destroyerNo ratings yet

- Bones and Skeletal Tissue Matching QuestionsDocument10 pagesBones and Skeletal Tissue Matching Questionsjinni0926No ratings yet

- Basic Clinical Massage TherapyDocument654 pagesBasic Clinical Massage Therapykkism100% (11)

- Master Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery Knee11Document1,137 pagesMaster Techniques in Orthopaedic Surgery Knee11Ameer Ali100% (5)

- Muscles QuestionsDocument3 pagesMuscles QuestionsIRADUKUNDA Marie SolangeNo ratings yet

- Paulchek PDFDocument20 pagesPaulchek PDFSakip HirrimNo ratings yet

- Fracture Neck FemurDocument50 pagesFracture Neck FemurdrabhishekorthoNo ratings yet

- Principle of Fracture Management: Dr. Miawa RobertDocument63 pagesPrinciple of Fracture Management: Dr. Miawa Robertkajojo joyNo ratings yet

- Back Exercises: Hamstring StretchDocument5 pagesBack Exercises: Hamstring StretchsreeeeeNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Starting PositionDocument28 pagesFundamental Starting PositionShobhit SainiNo ratings yet

- Sever's Disease A Guide To The Causes, Symptoms, & TreatmentDocument9 pagesSever's Disease A Guide To The Causes, Symptoms, & TreatmentMikkel JarmanNo ratings yet

- Current Golf Performance Literature and Application To TrainingDocument11 pagesCurrent Golf Performance Literature and Application To TrainingdesignkebasNo ratings yet

- AkupunturDocument245 pagesAkupunturaufa ahdi100% (3)

- Essential Joint MovementsDocument52 pagesEssential Joint MovementsKhairul Hanan100% (5)

- Bone Fracture Classification and Healing StagesDocument11 pagesBone Fracture Classification and Healing StagesAmal ShereefNo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy Techniques for the Thoracic SpineDocument31 pagesManual Therapy Techniques for the Thoracic SpineMita SuryatniNo ratings yet