Professional Documents

Culture Documents

8 Planets and Counting

Uploaded by

madeline maeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

8 Planets and Counting

Uploaded by

madeline maeCopyright:

Available Formats

Overview

There are more planets than stars in our galaxy. The current count

orbiting our star: eight.

The inner, rocky planets are Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. The outer

planets are gas giants Jupiter and Saturn and ice

giants Uranus and Neptune.

Beyond Neptune, a newer class of smaller worlds called dwarf planets

reign, including perennial favorite Pluto.

What is a Planet?

This seemingly simple question doesn't have a simple answer. Everyone

knows that Earth, Mars and Jupiter are planets. But

both Pluto and Ceres were once considered planets until new

discoveries triggered scientific debate about how to best describe

them—a vigorous debate that continues to this day. The most

recent definition of a planet was adopted by the International

Astronomical Union in 2006. It says a planet must do three things:

1. It must orbit a star (in our cosmic neighborhood, the Sun).

2. It must be big enough to have enough gravity to force it into a spherical

shape.

3. It must be big enough that its gravity cleared away any other objects of a

similar size near its orbit around the Sun.

Discussion—and debate—will continue as our view of the cosmos

continues to expand.

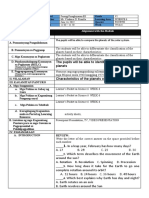

The Scientific Process

Science is a dynamic process of questioning, hypothesizing, discovering,

and changing previous ideas based on what is learned. Scientific ideas

are developed through reasoning and tested against observations.

Scientists assess and question each other's work in a critical process

called peer review.

Our understanding about the universe and our place in it has changed

over time. New information can cause us to rethink what we know and

reevaluate how we classify objects in order to better understand them.

New ideas and perspectives can come from questioning a theory or

seeing where a classification breaks down.

An Evolving Definition

Defining the term planet is important, because such definitions reflect

our understanding of the origins, architecture, and evolution of our solar

system. Over historical time, objects categorized as planets have

changed. The ancient Greeks counted the Earth's Moon and Sun as

planets along with Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Earth was

not considered a planet, but rather was thought to be the central object

around which all the other celestial objects orbited. The first known

model that placed the Sun at the center of the known universe with the

Earth revolving around it was presented by Aristarchus of Samos in the

third century BCE, but it was not generally accepted. It wasn't until the

16th century that the idea was revived by Nicolaus Copernicus.

By the 17th century, astronomers (aided by the invention of the

telescope) realized that the Sun was the celestial object around which all

the planets—including Earth—orbit, and that the moon is not a planet,

but a satellite (moon) of Earth. Uranus was added as a planet in 1781

and Neptune was discovered in 1846.

Ceres was discovered between Mars and Jupiter in 1801 and originally

classified as a planet. But as many more objects were subsequently

found in the same region, it was realized that Ceres was the first of a

class of similar objects that were eventually termed asteroids (star-like)

or minor planets.

Pluto, discovered in 1930, was identified as the ninth planet. But Pluto is

much smaller than Mercury and is even smaller than some of the

planetary moons. It is unlike the terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus,

Earth, Mars), or the gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn), or the ice giants

(Uranus, Neptune). Charon, its huge satellite, is nearly half the size of

Pluto and shares Pluto's orbit. Though Pluto kept its planetary status

through the 1980s, things began to change in the 1990s with some new

discoveries.

Technical advances in telescopes led to better observations and

improved detection of very small, very distant objects. In the early 1990s,

astronomers began finding numerous icy worlds orbiting the Sun in a

doughnut-shaped region called the Kuiper Belt beyond the orbit of

Neptune—out in Pluto's realm. With the discovery of the Kuiper Belt and

its thousands of icy bodies (known as Kuiper Belt Objects, or KBOs; also

called transneptunians), it was proposed that it is more useful to think of

Pluto as the biggest KBO instead of a planet.

The Planet Debate

Then, in 2005, a team of astronomers announced that they had found a

tenth planet—it was a KBO similar in size to Pluto. People began to

wonder what planethood really means. Just what is a planet, anyway?

Suddenly the answer to that question didn't seem so self-evident, and,

as it turns out, there are plenty of disagreements about it.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU), a worldwide organization of

astronomers, took on the challenge of classifying the newly found KBO

(later named Eris). In 2006, the IAU passed a resolution that defined

planet and established a new category, dwarf planet. Eris, Ceres, Pluto,

and two more recently discovered KBOs named Haumea and

Makemake, are the dwarf planets recognized by the IAU. There may be

another 100 dwarf planets in the solar system and hundreds more in and

just outside the Kuiper Belt.

The New Definition of Planet

Here is the text of the IAU’s Resolution B5: Definition of a Planet in the

Solar System:

Contemporary observations are changing our understanding of planetary

systems, and it is important that our nomenclature for objects reflect our

current understanding. This applies, in particular, to the designation

"planets". The word "planet" originally described "wanderers" that were

known only as moving lights in the sky. Recent discoveries lead us to

create a new definition, which we can make using currently available

scientific information.

The IAU therefore resolves that planets and other bodies, except

satellites, in our Solar System be defined into three distinct categories in

the following way:

1. A planet is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b) has

sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so that it

assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, and (c) has

cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit.

2. A "dwarf planet" is a celestial body that (a) is in orbit around the Sun, (b)

has sufficient mass for its self-gravity to overcome rigid body forces so

that it assumes a hydrostatic equilibrium (nearly round) shape, (c) has

not cleared the neighbourhood around its orbit, and (d) is not a satellite.

3. All other objects,except satellites, orbiting the Sun shall be referred to

collectively as "Small Solar System Bodies".

Debate—and Discoveries—Continue

Astronomers and planetary scientists did not unanimously agree with

these definitions. To some it appeared that the classification scheme

was designed to limit the number of planets; to others it was incomplete

and the terms unclear. Some astronomers argued that location (context)

is important, especially in understanding the formation and evolution of

the solar system.

One idea is to simply define a planet as a natural object in space that is

massive enough for gravity to make it approximately spherical. But some

scientists objected that this simple definition does not take into account

what degree of measurable roundness is needed for an object to be

considered round. In fact, it is often difficult to accurately determine the

shapes of some distant objects. Others argue that where an object is

located or what it is made of do matter and there should not be a

concern with dynamics; that is, whether or not an object sweeps up or

scatters away its immediate neighbors, or holds them in stable orbits.

The lively planethood debate continues.

As our knowledge deepens and expands, the more complex and

intriguing the universe appears. Researchers have found hundreds of

extrasolar planets, or exoplanets, that reside outside our solar system;

there may be billions of exoplanets in the Milky Way Galaxy alone, and

some may be habitable (have conditions favorable to life). Whether our

definitions of planet can be applied to these newly found objects remains

to be seen.

You might also like

- PLANETDocument3 pagesPLANETMatej IvanovskiNo ratings yet

- PrssDocument11 pagesPrssPrawin SanjaiNo ratings yet

- 14 Fun Facts About the Solar System: A 15-Minute BookFrom Everand14 Fun Facts About the Solar System: A 15-Minute BookRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Dwarf PlanetsDocument13 pagesDwarf PlanetsZiela RazalliNo ratings yet

- Planet: A Wandering StarDocument2 pagesPlanet: A Wandering StarsorrowdzordsssNo ratings yet

- Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, How I Wonder What You Are: Concise Introduction to CosmologyFrom EverandTwinkle Twinkle Little Star, How I Wonder What You Are: Concise Introduction to CosmologyNo ratings yet

- Planet: A Is An A or That Is Massive Enough To Be by Its Own, Is Not Massive Enough To Cause, and Has ofDocument3 pagesPlanet: A Is An A or That Is Massive Enough To Be by Its Own, Is Not Massive Enough To Cause, and Has ofCFK TaborNo ratings yet

- Astronomy for Beginners: Ideal guide for beginners on astronomy, the Universe, planets and cosmologyFrom EverandAstronomy for Beginners: Ideal guide for beginners on astronomy, the Universe, planets and cosmologyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The plNETDocument1 pageThe plNETvinayNo ratings yet

- PlanetsDocument1 pagePlanetsapi-258996317No ratings yet

- The Solar System: Out of This World with Science Activities for KidsFrom EverandThe Solar System: Out of This World with Science Activities for KidsNo ratings yet

- Order of the Planets from the SunDocument2 pagesOrder of the Planets from the SunMudau Khumbelo RodneykNo ratings yet

- 14 Fun Facts About Dwarf Planets: A 15-Minute BookFrom Everand14 Fun Facts About Dwarf Planets: A 15-Minute BookRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Solar System Planets2222Document14 pagesSolar System Planets2222Eina Reyes RocilloNo ratings yet

- Earth and Life Science OutlineDocument6 pagesEarth and Life Science OutlineYveth CruzNo ratings yet

- The Planets: Photographs from the Archives of NASAFrom EverandThe Planets: Photographs from the Archives of NASARating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- GeographyDocument4 pagesGeographyAnu GangeleNo ratings yet

- Planet: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchDocument37 pagesPlanet: Jump To Navigationjump To SearchIorga IonutNo ratings yet

- What Is The Definition of A ?: PlanetDocument8 pagesWhat Is The Definition of A ?: PlanetWilliam CiferNo ratings yet

- PlanetsDocument2 pagesPlanetsbliadzeirakli19No ratings yet

- Earth Science Geology AssignmentDocument52 pagesEarth Science Geology AssignmentChristine MaeNo ratings yet

- Asteroids, Meteors, Comets: Titles in This SeriesDocument65 pagesAsteroids, Meteors, Comets: Titles in This SeriesDiana Roxana Ciobanu100% (1)

- Wiki Dwarf PlanetsDocument179 pagesWiki Dwarf PlanetsRamón PerisNo ratings yet

- International Astronomical UnionDocument5 pagesInternational Astronomical UnionShihabsirNo ratings yet

- Explore the Solar SystemDocument22 pagesExplore the Solar SystemVincent LicupNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Solar SystemDocument8 pagesIntroduction To The Solar SystemDayanna AtauchiNo ratings yet

- Updated Pluto, the Dwarf PlanetDocument1 pageUpdated Pluto, the Dwarf PlanetyoonglesNo ratings yet

- Definiton - FinalDocument8 pagesDefiniton - Finalapi-459458801No ratings yet

- Mission Pluto PassageDocument3 pagesMission Pluto Passageapi-279192630100% (1)

- NatSci TAPOS NA!!!!!-Final TFDocument54 pagesNatSci TAPOS NA!!!!!-Final TFWendyMayVillapaNo ratings yet

- Planets in our solar system and beyondDocument2 pagesPlanets in our solar system and beyondKwammy BrownNo ratings yet

- Origin of UniverseDocument10 pagesOrigin of Universehaider-ijaz-4545No ratings yet

- Solar SystemDocument12 pagesSolar SystemDeepak Lohar DLNo ratings yet

- Solar SystemDocument3 pagesSolar SystemKim CatherineNo ratings yet

- Planets 2Document3 pagesPlanets 2ferasbh1303No ratings yet

- Earth and Life Week 1Document8 pagesEarth and Life Week 1Jericho CunananNo ratings yet

- What Is A Planet?: OverviewDocument36 pagesWhat Is A Planet?: Overviewnancy.rubin2477No ratings yet

- Pluto_Urquhart_06Document5 pagesPluto_Urquhart_06yoonglesNo ratings yet

- Pluto's planetary status debated as New Horizons images reignite old argumentDocument5 pagesPluto's planetary status debated as New Horizons images reignite old argumentMary Ann Xyza OcioNo ratings yet

- (Astēr Planētēs), Meaning "Wandering Star") IsDocument10 pages(Astēr Planētēs), Meaning "Wandering Star") Isaditya2053No ratings yet

- Why Is Pluto No Longer A Planet?Document3 pagesWhy Is Pluto No Longer A Planet?engr_rimNo ratings yet

- The Solar SystemDocument11 pagesThe Solar SystemDaniela StaciNo ratings yet

- Essay About Solar SystemDocument7 pagesEssay About Solar SystemRosechelle HinalNo ratings yet

- A Journey Through Space and TimeDocument22 pagesA Journey Through Space and TimeSeptian Hadi NugrahaNo ratings yet

- L-7 Solar SystemDocument5 pagesL-7 Solar SystemKhushi KotwaniNo ratings yet

- (DALIDA) Formation of The Solar SystemDocument3 pages(DALIDA) Formation of The Solar SystemkathleenmaerdalidaNo ratings yet

- What Is A PlanetDocument24 pagesWhat Is A PlanetardeegeeNo ratings yet

- 2ND TERM - Earth ScienceDocument17 pages2ND TERM - Earth ScienceRaals Internet CafeNo ratings yet

- Planet: This Article Is About The Astronomical Object. For Other Uses, SeeDocument4 pagesPlanet: This Article Is About The Astronomical Object. For Other Uses, SeeArjel JamiasNo ratings yet

- Discovery: Infographic: Structure of The Solar System A True Ninth PlanetDocument1 pageDiscovery: Infographic: Structure of The Solar System A True Ninth PlanetMarlette NunesNo ratings yet

- Sistemaa SolarDocument11 pagesSistemaa SolarEnrique GranadosNo ratings yet

- Solar SystemDocument42 pagesSolar SystemdrvoproNo ratings yet

- News Tech Spaceflight Science & Astronomy Search For Life Skywatching EntertainmentDocument33 pagesNews Tech Spaceflight Science & Astronomy Search For Life Skywatching EntertainmentdannaalissezabatNo ratings yet

- Pluto From Planet X To Ex-PlanetDocument7 pagesPluto From Planet X To Ex-PlanetThavam RatnaNo ratings yet

- T Par 605 The Universe Information Powerpoint Ver 1Document12 pagesT Par 605 The Universe Information Powerpoint Ver 1meraa montaserNo ratings yet

- FDocument8 pagesFdiego rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Final Chapter 2Document7 pagesFinal Chapter 2EmamMsHome-hyhy0% (1)

- Internet. Written and Presented by John Heilemann, The Series Explores The Emergence andDocument9 pagesInternet. Written and Presented by John Heilemann, The Series Explores The Emergence andmadeline maeNo ratings yet

- Technical Design DocumentDocument21 pagesTechnical Design Documentmanderin87No ratings yet

- Input Process Output: Management Information System Database ManagementDocument1 pageInput Process Output: Management Information System Database Managementmadeline maeNo ratings yet

- Input Process Output: Management Information System Database ManagementDocument1 pageInput Process Output: Management Information System Database Managementmadeline maeNo ratings yet

- THESIS Mobile Phone UsageDocument24 pagesTHESIS Mobile Phone UsageSharreah Lim70% (43)

- Revme: The Usability of Mobile Application Reviewer For The Preparation For College Entrance ExamDocument34 pagesRevme: The Usability of Mobile Application Reviewer For The Preparation For College Entrance Exammadeline maeNo ratings yet

- Instruction On Problem 2 SDocument3 pagesInstruction On Problem 2 Smadeline maeNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument3 pagesReview of Related Literature and Studiesmadeline maeNo ratings yet

- 8 Planets and CountingDocument6 pages8 Planets and Countingmadeline maeNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument8 pagesReview of Related Literature and Studiesmadeline maeNo ratings yet

- WebdevDocument1 pageWebdevmadeline maeNo ratings yet

- The Solar System & Its OriginsDocument32 pagesThe Solar System & Its OriginsFany FabiaNo ratings yet

- Business Trip Organization Proposal by SlidesgoDocument50 pagesBusiness Trip Organization Proposal by SlidesgoSwesty ParamithaNo ratings yet

- Dark EarthDocument90 pagesDark EarthJay Alfred100% (2)

- PIVOT IDEA Lesson Exemplar Format Alignment With The ModuleDocument7 pagesPIVOT IDEA Lesson Exemplar Format Alignment With The ModuleVladimer PionillaNo ratings yet

- Time and The Cosmos: The Orrery in The Eighteenth-Century ImaginationDocument25 pagesTime and The Cosmos: The Orrery in The Eighteenth-Century Imaginationari sudrajatNo ratings yet

- Global Technology Investments Project Proposal InfographicsDocument35 pagesGlobal Technology Investments Project Proposal Infographicsaljc2517No ratings yet

- Kawaii Style Book Slideshow For Marketing by SlidesgoDocument58 pagesKawaii Style Book Slideshow For Marketing by Slidesgoalissyah maharaniNo ratings yet

- Recipes Workshop To Celebrate National Cinnamon DayDocument61 pagesRecipes Workshop To Celebrate National Cinnamon Daysbbj4rhxf7No ratings yet

- Introduction of SaturnDocument2 pagesIntroduction of SaturnElla Mae Kate GoopioNo ratings yet

- Những kỹ năng sinh viên cần phải có sau khi tốt nghiệp: Here is where your presentation beginsDocument41 pagesNhững kỹ năng sinh viên cần phải có sau khi tốt nghiệp: Here is where your presentation beginsLê Văn SơnNo ratings yet

- The Life of Galileo - Bertolt BrechtDocument98 pagesThe Life of Galileo - Bertolt BrechtCA_Ken100% (1)

- Medieval Symbols and the Origins of Astrological IconsDocument104 pagesMedieval Symbols and the Origins of Astrological IconsUUMhawSayar100% (1)

- Starbucks Coffe Company: Presentado Por: Nadine Margot Zamudio LazarteDocument69 pagesStarbucks Coffe Company: Presentado Por: Nadine Margot Zamudio LazarteNADINE MARGOT ZAMUDIO LAZARTENo ratings yet

- Le Fonds Z Translation 3Document16 pagesLe Fonds Z Translation 3AndrewNo ratings yet

- Travel Guide BaliDocument53 pagesTravel Guide BaliAfandi Pratama putraNo ratings yet

- Cambridge Science P2 2016Document24 pagesCambridge Science P2 2016Makanaka SambureniNo ratings yet

- Sistemul Solar Carte de ColoratDocument13 pagesSistemul Solar Carte de ColoratAlina CrihanNo ratings yet

- NCERT Class 6 Geography Chapter 1 YouTube Lecture HandoutsDocument5 pagesNCERT Class 6 Geography Chapter 1 YouTube Lecture Handoutskalasri100% (1)

- Grade6 SLM Q4 Module7 Construct A Model of The Solar System ApprovedDocument17 pagesGrade6 SLM Q4 Module7 Construct A Model of The Solar System ApprovedAsorihm Mhirosa100% (1)

- SOAL BAHASA INGGRIS PAS SD 2021 Kelas 6Document3 pagesSOAL BAHASA INGGRIS PAS SD 2021 Kelas 6Dewi Karunia DinaNo ratings yet

- Adaptive Optics QuestionsDocument16 pagesAdaptive Optics QuestionsPam SNo ratings yet

- Traveler's Guide To The Planets-Nick RobinsonDocument9 pagesTraveler's Guide To The Planets-Nick RobinsonNick RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Researc H Project: Here Is Where Your Presentation BeginsDocument44 pagesResearc H Project: Here Is Where Your Presentation BeginsYovi PratamaNo ratings yet

- Grade XI: United New-Model QuestionsDocument206 pagesGrade XI: United New-Model QuestionsRa0% (1)

- Parapsychology & Anomalistic Psychology: Prepared By: Marvin Jay S. FarralesDocument57 pagesParapsychology & Anomalistic Psychology: Prepared By: Marvin Jay S. Farralesmarvin jayNo ratings yet

- Voyager Bulletin (Mission Status Report) No. 1-67Document174 pagesVoyager Bulletin (Mission Status Report) No. 1-67goldfires100% (2)

- Animated Healthcare Center by SlidesgoDocument57 pagesAnimated Healthcare Center by SlidesgojavierNo ratings yet

- Abdul - Wadud - Phenomena of Nature and The QuranDocument326 pagesAbdul - Wadud - Phenomena of Nature and The QuranadilNo ratings yet

- Read 100 Easy General Knowledge Questions and Answers Quiz For f6Document21 pagesRead 100 Easy General Knowledge Questions and Answers Quiz For f6erin50% (2)

- BioethicsDocument55 pagesBioethicsEzekiel John GarciaNo ratings yet

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Techniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementFrom EverandTechniques Exercises And Tricks For Memory ImprovementRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (40)

- Chakras and Yoga: Finding Inner Harmony Through Practice, Awaken the Energy Centers for Optimal Physical and Spiritual Health.From EverandChakras and Yoga: Finding Inner Harmony Through Practice, Awaken the Energy Centers for Optimal Physical and Spiritual Health.Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Breaking the Habit of Being YourselfFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1456)

- The Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandThe Ultimate Guide To Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (34)

- Natural Memory Improvement TechniquesFrom EverandNatural Memory Improvement TechniquesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (54)

- The Subconscious Mind Superpower: How to Unlock the Powerful Force of Your Subconscious MindFrom EverandThe Subconscious Mind Superpower: How to Unlock the Powerful Force of Your Subconscious MindRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (127)

- Neville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!From EverandNeville Goddard Master Course to Manifest Your Desires Into Reality Using The Law of Attraction: Learn the Secret to Overcoming Your Current Problems and Limitations, Attaining Your Goals, and Achieving Health, Wealth, Happiness and Success!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (284)

- Deep Sleep Meditation: Fall Asleep Instantly with Powerful Guided Meditations, Hypnosis, and Affirmations. Overcome Anxiety, Depression, Insomnia, Stress, and Relax Your Mind!From EverandDeep Sleep Meditation: Fall Asleep Instantly with Powerful Guided Meditations, Hypnosis, and Affirmations. Overcome Anxiety, Depression, Insomnia, Stress, and Relax Your Mind!Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)

- The Creation Frequency: Tune In to the Power of the Universe to Manifest the Life of Your DreamsFrom EverandThe Creation Frequency: Tune In to the Power of the Universe to Manifest the Life of Your DreamsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (549)

- No Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingFrom EverandNo Mud, No Lotus: The Art of Transforming SufferingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (173)

- A New Science of the Afterlife: Space, Time, and the Consciousness CodeFrom EverandA New Science of the Afterlife: Space, Time, and the Consciousness CodeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (33)

- 369: Manifesting Through 369 and the Law of Attraction - METHODS, TECHNIQUES AND EXERCISESFrom Everand369: Manifesting Through 369 and the Law of Attraction - METHODS, TECHNIQUES AND EXERCISESRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (50)

- Breaking the Habit of Being Yourself by Joe Dispenza - Book Summary: How to Lose Your Mind and Create a New OneFrom EverandBreaking the Habit of Being Yourself by Joe Dispenza - Book Summary: How to Lose Your Mind and Create a New OneRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (123)

- Notes from the Universe: New Perspectives from an Old FriendFrom EverandNotes from the Universe: New Perspectives from an Old FriendRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (53)

- Quantum Spirituality: Science, Gnostic Mysticism, and Connecting with Source ConsciousnessFrom EverandQuantum Spirituality: Science, Gnostic Mysticism, and Connecting with Source ConsciousnessRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- Conversations with Nostradamus, Vol I: His Prophecies ExplainedFrom EverandConversations with Nostradamus, Vol I: His Prophecies ExplainedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (83)

- Spellbound: Modern Science, Ancient Magic, and the Hidden Potential of the Unconscious MindFrom EverandSpellbound: Modern Science, Ancient Magic, and the Hidden Potential of the Unconscious MindRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- The Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeFrom EverandThe Secret of the Golden Flower: A Chinese Book Of LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Infinite Potential: The Greatest Works of Neville GoddardFrom EverandInfinite Potential: The Greatest Works of Neville GoddardRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (192)

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseFrom EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (69)

- The Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYFrom EverandThe Secret Teachings Of All Ages: AN ENCYCLOPEDIC OUTLINE OF MASONIC, HERMETIC, QABBALISTIC AND ROSICRUCIAN SYMBOLICAL PHILOSOPHYRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthFrom EverandThe Three Waves of Volunteers & The New EarthRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (179)

- The Beginner's Guide to the Akashic Records: The Understanding of Your Soul's History and How to Read ItFrom EverandThe Beginner's Guide to the Akashic Records: The Understanding of Your Soul's History and How to Read ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (10)