Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ws

Ws

Uploaded by

Piyush Raj0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views1 pageWs

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentWs

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views1 pageWs

Ws

Uploaded by

Piyush RajWs

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

In 1878 a hydroelectric power station was designed and built by Lord

Armstrong at Cragside, England. It used water from lakes on his estate to

power Siemens dynamos. The electricity supplied power to lights, heating, produced hot

water, ran an elevator as well as labor-saving devices and farm buildings.[1]

In the early 1870s Belgian inventor Zénobe Gramme invented a generator powerful

enough to produce power on a commercial scale for industry.[2]

In the autumn of 1882, a central station providing public power was built in Godalming,

England. It was proposed after the town failed to reach an agreement on the rate

charged by the gas company, so the town council decided to use electricity. It used

hydroelectric power for street lighting and household lighting. The system was not a

commercial success and the town reverted to gas.[3]

In 1882 the world's first coal-fired public power station, the Edison Electric Light Station,

was built in London, a project of Thomas Edison organized by Edward Johnson.

A Babcock & Wilcox boiler powered a 125-horsepower steam engine that drove a 27-ton

generator. This supplied electricity to premises in the area that could be reached

through the culverts of the viaduct without digging up the road, which was the monopoly

of the gas companies. The customers included the City Templeand the Old Bailey.

Another important customer was the Telegraph Office of the General Post Office, but this

could not be reached though the culverts. Johnson arranged for the supply cable to be

run overhead, via Holborn Tavern and Newgate.[4]

In September 1882 in New York, the Pearl Street Station was established by Edison to

provide electric lighting in the lower Manhattan Island area. The station ran until

destroyed by fire in 1890. The station used reciprocating steam engines to turn direct-

current generators. Because of the DC distribution, the service area was small, limited

by voltage drop in the feeders. In 1886 George Westinghouse began building an

alternating current system that used a transformer to step up voltage for long-distance

transmission and then stepped it back down for indoor lighting, a more efficient and less

expensive system which is similar to modern systems. The War of Currents eventually

resolved in favor of AC distribution and utilization, although some DC systems persisted

to the end of the 20th century. DC systems with a service radius of a mile (kilometer) or

so were necessarily smaller, less efficient of fuel consumption, and more labor-intensive

to operate than much larger central AC generating stations.

You might also like

- 3.1. Schematic Explorer View Schematic Explorer: 3 Working With The Diagrams ApplicationDocument4 pages3.1. Schematic Explorer View Schematic Explorer: 3 Working With The Diagrams ApplicationMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- GWWDDocument3 pagesGWWDMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- XsxefcrDocument5 pagesXsxefcrMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- New SCGROUP: Schematic Group Rename Apply Dismiss: All Button Can Be UsedDocument3 pagesNew SCGROUP: Schematic Group Rename Apply Dismiss: All Button Can Be UsedMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- Savework / Getwork SaveworkDocument4 pagesSavework / Getwork SaveworkMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- Y FDN GD Kfy GD DN: K FD DDocument5 pagesY FDN GD Kfy GD DN: K FD DMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- Weights Are All Non-Negative and For Any Value of The Parameter, They Sum To UnityDocument2 pagesWeights Are All Non-Negative and For Any Value of The Parameter, They Sum To UnityMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- Check Opc Types: V-111S Process VesselDocument1 pageCheck Opc Types: V-111S Process VesselMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- Gate Solved Paper - Me: X Aq Q y A Q Dy Q Q Q QDocument51 pagesGate Solved Paper - Me: X Aq Q y A Q Dy Q Q Q QMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- 2.6 Computer Aided Assembly of Rigid Bodies: P P Q Q P P QDocument4 pages2.6 Computer Aided Assembly of Rigid Bodies: P P Q Q P P QMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- 00 PDFDocument2 pages00 PDFMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- New Doc 2017-07-27 - 1Document1 pageNew Doc 2017-07-27 - 1Mayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

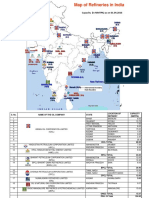

- RefineriesMap PDFDocument2 pagesRefineriesMap PDFMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- 01 PDFDocument2 pages01 PDFMayur MandrekarNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Ec Declaration of Conformity: QAS60 PDS 400 V 50 HZDocument6 pagesEc Declaration of Conformity: QAS60 PDS 400 V 50 HZFernando Morales PachonNo ratings yet

- ATV61 Communication Parameters en V5.8 IE29Document126 pagesATV61 Communication Parameters en V5.8 IE29Anonymous kiyxz6eNo ratings yet

- Medical Store ManagementDocument31 pagesMedical Store Managementakhilesh50% (2)

- Modicon M251 - Programming Guide EIO0000003089.02Document270 pagesModicon M251 - Programming Guide EIO0000003089.02mariookkNo ratings yet

- Mosquetes Political Economy of The Philippines Transportation LRT MRT Issues and How It Affects The Filipino WorkersDocument12 pagesMosquetes Political Economy of The Philippines Transportation LRT MRT Issues and How It Affects The Filipino WorkersLouisky MosquetesNo ratings yet

- For Moment of Inertia For PSC GirderDocument6 pagesFor Moment of Inertia For PSC GirderAshutosh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Class 6 Social PaperDocument5 pagesClass 6 Social PaperManav RachchhNo ratings yet

- Wang 2016Document7 pagesWang 2016Hadiza PebramaNo ratings yet

- V60N en PDFDocument64 pagesV60N en PDFY.EbadiNo ratings yet

- w505 NX Nj-Series Cpu Unit Built-In Ethercat Port Users Manual en PDFDocument288 pagesw505 NX Nj-Series Cpu Unit Built-In Ethercat Port Users Manual en PDFfaspNo ratings yet

- Keyboard ShortcutsDocument11 pagesKeyboard Shortcutsashscribd_idNo ratings yet

- All Progressive Circle Wise & Cadar Wise Summery Status 01-03-2024Document25 pagesAll Progressive Circle Wise & Cadar Wise Summery Status 01-03-2024vivekNo ratings yet

- Java-Frequently Asked Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesJava-Frequently Asked Interview QuestionsS.S. AmmarNo ratings yet

- Neil Armstrong BiographyDocument4 pagesNeil Armstrong Biographyapi-232002863No ratings yet

- ARCS and ORCS User Guide: Revision HistoryDocument17 pagesARCS and ORCS User Guide: Revision HistoryHasain AhmedNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Physiology Chapter 1 Practice TestDocument13 pagesAnatomy and Physiology Chapter 1 Practice TestDani AnyikaNo ratings yet

- Emailing Teacher Notes PDFDocument2 pagesEmailing Teacher Notes PDFSylwia WęglewskaNo ratings yet

- Crafting The Brand Positioning: Marketing Management, 13 EdDocument21 pagesCrafting The Brand Positioning: Marketing Management, 13 Edannisa maulidinaNo ratings yet

- IoT Based Low-Cost Gas Leakage 2020Document6 pagesIoT Based Low-Cost Gas Leakage 2020Sanjevi PNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document35 pagesLesson 1Irish GandolaNo ratings yet

- SET 1 - MOCK ALE Day 2 Design ProblemsDocument6 pagesSET 1 - MOCK ALE Day 2 Design Problemsallyssa monica duNo ratings yet

- IMO Shortlist 2010Document72 pagesIMO Shortlist 2010Florina TomaNo ratings yet

- University Assignment Report CT7098Document16 pagesUniversity Assignment Report CT7098Shakeel ShahidNo ratings yet

- DFT Notes PDFDocument4 pagesDFT Notes PDFkrishna prasad ghantaNo ratings yet

- Itwc PDFDocument8 pagesItwc PDFA MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Standalone Kitchen Model WorkingDocument3 pagesStandalone Kitchen Model WorkingSujith psNo ratings yet

- Group 2I - Herman Miller Case AnalysisDocument7 pagesGroup 2I - Herman Miller Case AnalysisRishabh Kothari100% (1)

- Sample High School Argumentative EssayDocument1 pageSample High School Argumentative EssayAllihannah PhillipsNo ratings yet

- In The West, The Shadow of The Gnomon Points East (As Shown in The Pictures Below)Document7 pagesIn The West, The Shadow of The Gnomon Points East (As Shown in The Pictures Below)ShanmugasundaramNo ratings yet

- Arts 6 Module 1Document18 pagesArts 6 Module 1Elexthéo JoseNo ratings yet