Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Guidance On Research Proposal PDF

Guidance On Research Proposal PDF

Uploaded by

bibinantOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Guidance On Research Proposal PDF

Guidance On Research Proposal PDF

Uploaded by

bibinantCopyright:

Available Formats

Applications for PhD/MPhil in English Literature

Your research proposal

The two elements of an application that are most useful to us when we consider a candidate

for the PhD or MPhil degrees are the sample of written work and the research proposal.

You will probably choose your sample of written work from an already-completed

undergraduate or masters-level dissertation or term-paper. Your research proposal will be

something new. It will describe the project that you want to complete for the award of the

MPhil or PhD. Take your time in composing your research proposal, and consider carefully

the requirements outlined below. Your research proposal should not be more than 2,000

words long.

Research degrees are awarded on the basis of a thesis of up to 100,000 words (PhD) or up to

60,000 words (MPhil). The ‘Summary of roles and responsibilities’ in the University’s Code

of Practice for Supervisors and Research Students

http://www.docs.sasg.ed.ac.uk/AcademicServices/Codes/CoPSupervisorsResearchStudents.pdf

stipulates that a research thesis must

(i) show adequate knowledge of the field of study and relevant literature;

(ii) show the exercise of critical judgement with regard to both the candidate's work and that

of other scholars in the same general field;

(iii) contain material which presents a unified body of work such as could reasonably be

achieved on the basis of three years’ [full-time PhD] or two years’ [full-time MPhil]

postgraduate study and research; and

(iv) is satisfactory in its literary presentation, gives full and adequate references and has a

coherent structure understandable to a scholar in the same general field.

And the completed thesis in its final form should

(v) be an original work making a significant contribution to knowledge in or understanding

of the field of study;

(vi) contain material worthy of publication.

It is in the nature of research that, when you begin, you don’t know what you’ll find. This means

that your project is bound to change over the two or three years that you spend on it. So in

submitting your proposal you are not committing yourself absolutely to completing exactly the

project it describes in the event that you are accepted. Nevertheless, with the above points (i) to

(vi) in mind, your research proposal should include the following elements, though not

necessarily in this order:

1. An account of the body of primary texts that your thesis will examine. This may be

work by one author, or several, or many, depending on the nature of the project. It is very

unlikely to consist of a single text, however, unless that text is unusually compendious

(The Canterbury Tales) or unusually demanding (Finnegans Wake). Unless your range of

texts consists in the complete oeuvre of a single writer, you should explain why these

texts are the ones that need to be examined in order to make your particular argument.

2. An identification of the existing field or fields of criticism and scholarship of which

you will need to gain an ‘adequate knowledge’ (point i above) in order to complete your

thesis.

This must include work in existing literary criticism, broadly understood. Usually this

will consist of criticism or scholarship on the works or author(s) in question. In the case

of very recent writing, or writing marginal to the established literary canon, on which

there may be little or no existing critical work, it might include literary criticism written

on other works or authors in the same period, or related work in the same mode or genre,

or some other exercise of literary criticism that can serve as a reference point for your

engagement with this new material.

The areas of scholarship on which you draw are also likely to include work in other

disciplines, however. Most usually, these will be arguments in philosophy or critical

theory that have informed, or could inform, the critical debate around your primary texts,

or may have informed the texts themselves; and/or the historiography of the period in

which your texts were written or received. But we are ready to consider the possible

relevance of any other body of knowledge to literary criticism, as long as it is one with

which you are sufficiently familiar, or could become sufficiently familiar within the

period of your degree, for it to serve a meaningful role in your argument.

3. The questions or problems that the argument of your thesis will address; the methods

you will adopt to answer those questions or explain those problems; and some

explanation of why this particular methodology is the appropriate means of doing so. The

problem could take many forms: a simple gap in the existing scholarship that you will fill;

a misleading approach to the primary material that you will correct; or a difficulty in the

relation of the existing scholarship to theoretical/philosophical, historiographical, or other

disciplinary contexts, for example. But in any case, your thesis must engage critically

with the scholarship of others (point ii above) by mounting an original argument in

relation to the existing work in your field or fields. In this way your project must go

beyond the summarising of already-existing knowledge.

4. Finally, your proposal should include a provisional timetable, describing the stages

through which you hope your research would move, over the two or three years of your

degree. It is crucial that, on the one hand, your chosen topic should be substantial enough

to require around 50,000 words (MPhil) or 80,000 words (PhD) for its full exploration;

and, on the other hand, that it has clear limits which would allow it to be completed in

two years (MPhil) or three (PhD) (point iii above).

When drawing up this timetable, keep in mind that these word limits, and these time

constraints, will require you to complete 25–30,000 words of your thesis in each of the

years of your degree. If either of these degrees are taken on a part-time basis, the amount

of time available simply doubles.

In composing your research proposal you are already beginning the work that could lead, if you

are accepted, to the award of a research degree. Regard it, then, as a chance to refine and focus

your ideas, so that you can set immediately to work in an efficient manner on entry to the

university. But it bears repeating that that your project is bound to evolve beyond the project

described in your proposal in ways that you cannot at this stage predict. No-one can know, when

they begin any research work, where exactly it will take them. That provides much of the

pleasure of research, for the most distinguished professor as much as for the first-year research

student. If you are accepted as a candidate for the MPhil or the PhD in this department, you will

be joining a community of scholars still motivated by the thrill of finding and saying something

new.

RPI 10/10/11

You might also like

- Writing Your Dissertation Literature Review: A Step-by-Step GuideFrom EverandWriting Your Dissertation Literature Review: A Step-by-Step GuideRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (23)

- Understanding Essay Writing: A Guide To Writing Essays By Someone Who Grades ThemFrom EverandUnderstanding Essay Writing: A Guide To Writing Essays By Someone Who Grades ThemRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- SVA 2014 2015 Undergraduate and Graduate Registration BookDocument448 pagesSVA 2014 2015 Undergraduate and Graduate Registration BookCaseyConchinha100% (1)

- A Guide For A Full Time PHDDocument3 pagesA Guide For A Full Time PHDYogi ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- PHD TranscriptDocument3 pagesPHD TranscriptShubhangi GargNo ratings yet

- PHD Research Proposal GuidelinesDocument10 pagesPHD Research Proposal GuidelinesPragati ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Thesis ProposalDocument26 pagesThesis ProposalKrishna Karki50% (2)

- A GUIDE FOR A FULL TIME PHD PROPOSALDocument4 pagesA GUIDE FOR A FULL TIME PHD PROPOSALOkunola Wollex100% (1)

- 20 Steps To Teaching Unplugged: Englishagenda - SeminarsDocument4 pages20 Steps To Teaching Unplugged: Englishagenda - SeminarsLeticia Gomes AlvesNo ratings yet

- Singing Contest Judging FormDocument1 pageSinging Contest Judging FormSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Writing A Masters ThesisDocument11 pagesGuidelines For Writing A Masters ThesisGbenga Aliu100% (2)

- Midterm Examination CSCDocument7 pagesMidterm Examination CSCAimee SalangNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Research Proposal : GrantDocument14 pagesHow To Write A Research Proposal : GrantWendi WilliamsNo ratings yet

- how to write a successful research proposal كيف تكتب مقترح بحث ناجح: a successful research proposalFrom Everandhow to write a successful research proposal كيف تكتب مقترح بحث ناجح: a successful research proposalNo ratings yet

- The Philippine Century HenceDocument4 pagesThe Philippine Century HenceJean Inciong60% (5)

- Grille SyntheseDocument13 pagesGrille SynthesemohammadNo ratings yet

- Department of Media and Film 7u Dissertation Guide (8000 Word)Document7 pagesDepartment of Media and Film 7u Dissertation Guide (8000 Word)Christian BakerNo ratings yet

- Proposal S3 Di OtagoDocument3 pagesProposal S3 Di OtagoilkomNo ratings yet

- Alphacrucis College HDR ProgramDocument7 pagesAlphacrucis College HDR ProgramuniversitasbengkuluNo ratings yet

- MSC Dissertation Literature Review ExampleDocument8 pagesMSC Dissertation Literature Review ExampleBuyAPaperOnlineUK100% (1)

- Ma English Thesis PDFDocument4 pagesMa English Thesis PDFMohamed AchemlalNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Research ProposalDocument3 pagesHow To Write A Research ProposalMaria AvgeriNo ratings yet

- PHD Research PROPOSAL ArulampalamDocument4 pagesPHD Research PROPOSAL ArulampalamKHMHNNo ratings yet

- 5 Examiner Info PHD and Doctoral Theses Creative Works - New PolicyDocument3 pages5 Examiner Info PHD and Doctoral Theses Creative Works - New PolicyShuai ShaoNo ratings yet

- PGdissertationguidelinesDocument27 pagesPGdissertationguidelinesfelamendoNo ratings yet

- How Long Should A PHD Thesis Literature Review BeDocument6 pagesHow Long Should A PHD Thesis Literature Review BeafmzzulfmzbxetNo ratings yet

- (Soas) Guidelines For Writing Your Research Proposal PDFDocument1 page(Soas) Guidelines For Writing Your Research Proposal PDFMoh FathoniNo ratings yet

- Good PHD Thesis StructureDocument8 pagesGood PHD Thesis Structuredebradavisneworleans100% (2)

- Research - Proposal - Docx Filename UTF-8''Research ProposalDocument2 pagesResearch - Proposal - Docx Filename UTF-8''Research Proposalangelica eneriNo ratings yet

- College of Arts & Humanities: Writing A Research ProposalDocument3 pagesCollege of Arts & Humanities: Writing A Research ProposalbazylmazlNo ratings yet

- Sample Literature Review For Dissertation ProposalDocument8 pagesSample Literature Review For Dissertation ProposalWebsiteThatWillWriteAPaperForYouCanadaNo ratings yet

- General Information:: Title PageDocument3 pagesGeneral Information:: Title PageUsman SheikhNo ratings yet

- Thesis-Dissertation Proposal Template (English)Document5 pagesThesis-Dissertation Proposal Template (English)Christina RossettiNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis Writing IntroductionDocument7 pagesPHD Thesis Writing Introductiontujed1wov1f2100% (1)

- Theoretical Background Thesis ProposalDocument4 pagesTheoretical Background Thesis ProposalRick Vogel100% (2)

- Thesis-Proposal HKUDocument26 pagesThesis-Proposal HKUleegwapitoNo ratings yet

- What Should Be Included in A Master's Thesis Exposé in Sociology?Document3 pagesWhat Should Be Included in A Master's Thesis Exposé in Sociology?Giovanna DinizNo ratings yet

- Research Methods (WK 5-6) ExerciseDocument8 pagesResearch Methods (WK 5-6) ExerciseISAAC OURIENNo ratings yet

- Average Length Literature Review DissertationDocument4 pagesAverage Length Literature Review DissertationINeedSomeoneToWriteMyPaperUK100% (1)

- How Long Should A Literature Review Be in A DissertationDocument8 pagesHow Long Should A Literature Review Be in A DissertationWebsitesToTypePapersNorthLasVegasNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal U6410Document2 pagesResearch Proposal U6410u6410No ratings yet

- How To Write Introduction Chapter For PHD ThesisDocument7 pagesHow To Write Introduction Chapter For PHD Thesisangelaruizhartford100% (2)

- Guide To Producing A Research Proposal For Studies in PhilosophyDocument2 pagesGuide To Producing A Research Proposal For Studies in PhilosophyvcrepuljarevićNo ratings yet

- How To Write A Research ProposalDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Research ProposalAnkit SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Introduction Chapter OutlineDocument7 pagesThesis Introduction Chapter Outlinepatriciamedinadowney100% (2)

- How To Write A Project ProposalDocument3 pagesHow To Write A Project ProposalChuka Dennis OffodumNo ratings yet

- Meaning of Foreign Studies in ThesisDocument5 pagesMeaning of Foreign Studies in Thesisgjhr3grk100% (2)

- How To Write A Good Literature Review For PHD ThesisDocument8 pagesHow To Write A Good Literature Review For PHD Thesisc5m07hh9No ratings yet

- How To Write A Good Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesHow To Write A Good Literature Reviewaflskdwol100% (1)

- Writing A PHD Thesis IntroductionDocument6 pagesWriting A PHD Thesis Introductionykramhiig100% (2)

- Proposal Research DegreeDocument2 pagesProposal Research DegreeNiraj PandeyNo ratings yet

- What Is The Meaning of Review of Related Literature and StudiesDocument7 pagesWhat Is The Meaning of Review of Related Literature and Studiesea46krj6No ratings yet

- What Does A PHD Thesis Look Like (Session 1 Reading 3)Document8 pagesWhat Does A PHD Thesis Look Like (Session 1 Reading 3)findlotteNo ratings yet

- What Is A Literature Review DissertationDocument6 pagesWhat Is A Literature Review Dissertationtwfmadsif100% (1)

- How To Write A Research ProposalDocument4 pagesHow To Write A Research Proposaljaved765No ratings yet

- How To Write A Research Proposal PDFDocument3 pagesHow To Write A Research Proposal PDFMariglen DemiriNo ratings yet

- Thesis Guidebook For The Master of Arts in Clinical Psychology 2011-2012Document31 pagesThesis Guidebook For The Master of Arts in Clinical Psychology 2011-2012Justin MyersNo ratings yet

- Master Thesis Literature Review ExampleDocument8 pagesMaster Thesis Literature Review Exampleaflsldrzy100% (1)

- MEGILLHIEU+5062 2014 YES Phil and Theory of HistoryMK2Document5 pagesMEGILLHIEU+5062 2014 YES Phil and Theory of HistoryMK2eduardo_bvp610No ratings yet

- Difference Between Dissertation and Research PaperDocument5 pagesDifference Between Dissertation and Research PaperBuyCheapPapersOnlineCanadaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Dissertation StructureDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Dissertation Structurec5qp53ee100% (1)

- Sample Thesis Chapter 1 Conceptual FrameworkDocument7 pagesSample Thesis Chapter 1 Conceptual FrameworkWriteMyEnglishPaperForMeCanada100% (2)

- Research Proposal Writing Guidelines FINAL MS MPhil (Updated + Latest)Document11 pagesResearch Proposal Writing Guidelines FINAL MS MPhil (Updated + Latest)Chintoo MintooNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh University of Professionals (Bup)Document17 pagesBangladesh University of Professionals (Bup)oldschoolNo ratings yet

- Steps of Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesSteps of Literature Reviewafmzvulgktflda100% (1)

- Learn the Secrets of Writing Thesis: for High School, Undergraduate, Graduate Students and AcademiciansFrom EverandLearn the Secrets of Writing Thesis: for High School, Undergraduate, Graduate Students and AcademiciansNo ratings yet

- wf007 Nouns CrosswordDocument2 pageswf007 Nouns CrosswordSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- REVIEWSDocument10 pagesREVIEWSSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Cloze F3Document1 pageVocabulary Cloze F3Sanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Nouns You Nouns That Normally: Can Count. A / An Have A Plural Form. Can't Count. Don't Have A Plural FormDocument1 pageNouns You Nouns That Normally: Can Count. A / An Have A Plural Form. Can't Count. Don't Have A Plural FormSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

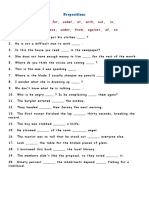

- PrepositionsDocument2 pagesPrepositionsSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- The 5-Paragraph EssayDocument14 pagesThe 5-Paragraph EssaySanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Essays 2Document33 pagesEssays 2Sanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Feelings. Emotional Outbursts)Document13 pagesFeelings. Emotional Outbursts)Sanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Weather Vocabulary: Word Meaning Example SentenceDocument5 pagesWeather Vocabulary: Word Meaning Example SentenceSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- English SUNDAY 5.2.2017: Class Time Skill / Element / AOT Domain Theme Topic Content StandardsDocument1 pageEnglish SUNDAY 5.2.2017: Class Time Skill / Element / AOT Domain Theme Topic Content StandardsSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Melancholy and ArchiveDocument143 pagesMelancholy and ArchiveSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Nicol David EssayDocument1 pageNicol David EssaySanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Time Parts of A Day: More Formal Less FormalDocument7 pagesTime Parts of A Day: More Formal Less FormalSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Dissertation TitlesDocument3 pagesDissertation TitlesSanggeetha RajendranNo ratings yet

- Chapter3 Nature's WarningDocument10 pagesChapter3 Nature's WarningSanggeetha Rajendran100% (1)

- Absurd Drama - Martin EsslinDocument12 pagesAbsurd Drama - Martin EsslinsunnysNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics 2017-18Document5 pagesThesis Topics 2017-18suraniNo ratings yet

- Persuasive EssayDocument8 pagesPersuasive Essayapi-457081827No ratings yet

- Chept 2Document50 pagesChept 2Ashish Kumar AmbastNo ratings yet

- JHA Chapter 1-5Document17 pagesJHA Chapter 1-5Megan Ramos IIINo ratings yet

- Harvard ReferencingDocument1 pageHarvard ReferencingMarya Fanta C LupuNo ratings yet

- Fashion CycleDocument18 pagesFashion CycleVeenu JainNo ratings yet

- Defining Women in Family Law: Amparita S. Sta. MariaDocument16 pagesDefining Women in Family Law: Amparita S. Sta. MariaxdesczaNo ratings yet

- 2.technical Writing in The Corporate World - (Section 3 Editing The Technical Document)Document12 pages2.technical Writing in The Corporate World - (Section 3 Editing The Technical Document)Andrea GarciaNo ratings yet

- HEL - Anglo Saxon - HistoryDocument24 pagesHEL - Anglo Saxon - HistoryTaimee AhmedNo ratings yet

- Cultural Diversity Worksheet Chapter 9 DHO BookDocument5 pagesCultural Diversity Worksheet Chapter 9 DHO BookbNo ratings yet

- NSFAMkbfDocument105 pagesNSFAMkbfAyashkanta RoutNo ratings yet

- Parts of A Research Report - 2018Document104 pagesParts of A Research Report - 2018GINABELLE COLIMA100% (1)

- Adverbs of MannerDocument2 pagesAdverbs of MannerAngélica Vidal PozúNo ratings yet

- Interview With Samir AminDocument36 pagesInterview With Samir AminKarlo Mikhail MongayaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan For Year 4 EnglishDocument4 pagesLesson Plan For Year 4 EnglishLee Ming YeoNo ratings yet

- Royal University of Phnom PenhDocument4 pagesRoyal University of Phnom PenhChem VathoNo ratings yet

- Elliott Chang - Teaching ResumeDocument1 pageElliott Chang - Teaching Resumeapi-321658972No ratings yet

- TO Rural Rural Sociology: Adnan Jalil AssiDocument51 pagesTO Rural Rural Sociology: Adnan Jalil AssiRana AnjumNo ratings yet

- Macaulay's Minutes 1835Document6 pagesMacaulay's Minutes 1835Dr. Aarif Hussain BhatNo ratings yet

- UNESCO Policy On Engaging With Indigenous PeoplesDocument37 pagesUNESCO Policy On Engaging With Indigenous PeoplesP R I N C E NNo ratings yet

- Principles and Parameters of Universal GrammarDocument32 pagesPrinciples and Parameters of Universal GrammarMaria Andreina Diaz SantanaNo ratings yet

- Ge Ssoc 1 Week8Document4 pagesGe Ssoc 1 Week8Jed DedNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument5 pagesConcept Paperlouie mosqueteNo ratings yet

- Adv Unit4 Lesson4cDocument3 pagesAdv Unit4 Lesson4cFatikun NajaNo ratings yet