Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pi Is 0140673697900325

Uploaded by

Yan Hein TanawaniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pi Is 0140673697900325

Uploaded by

Yan Hein TanawaniCopyright:

Available Formats

THE LANCET

Treatment of acute asthma

Brian J Lipworth

The drug treatment for acute severe asthma has changed inhaled l3-agonists, and is easy for the patient to use

little over the past two decades, comprising primarily of during an acute attack. 5 mg nebulised salbutamol driven

bronchodilators, corticosteroids, and oxygen. Most deaths by 6 IJmin oxygen has been shown to be a safe and

from acute severe asthma are potentially preventable and effective treatment when administered by trained

this requires recognition of severity of the attack and ambulance crew to patients with acute “severe asthma

delivery of optimum acute therapy, both in the during transfer to hospital.5 The potential concern

community and in hospital. regarding inadvertent carbon dioxide retention with high-

International and national guidelines have provided flow oxygen in patients with unsuspected chronic

evidence-based consensus statements on the management obstructive pulmonary disease is reduced by an age cut

of acute asthma in children and adults in general practice off of 50 years, along with diagnostic information from

and hospital settings.‘J Audit studies in the UK have the patient or general practitioner. Conventional open-

shown that many recommendations from previous vent jet nebulisers are, however, relatively inefficient

national guidelines have not been adhered to in either the devices with much of the nominal dose being wasted

community or hospital, and this suggests that wider during exhalation along with the residual volume at the

dissemination of the guidelines and improved education is end of nebulisation. Drug delivery to the lung depends on

required.3,4 the performance of the nebuliser chamber and an

As the international and national guidelines contain adequate flow rate from the compressor source. When 17

detailed algorithms for pathways of management in acute commercially available jet nebulisers were evaluated under

asthma exacerbations, it is not the intention to review the optimum operating conditions they showed an eight-fold

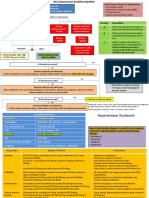

contents of these published reports here. A summary flow variation in the respirable dose delivered.6 The

chart for the treatment of acute severe asthma is shown in performance of a nebuliser may be further compounded

figure 1, based upon the key points from the international’ by variations in flow rate from a compressor which needs

and UK” management guidelines. The agenda for this to be, although rarely is, regularly maintained.

brief overview is to critically appraise some of the more A large-volume spacer device with a metered dose

contentious aspects of drug treatment in acute asthma, inhaler is an alternative means of delivery, which allows

but not to deal with initial assessment, follow-up, and tidal rebreathing with a mask or mouthpiece, and

patient education. On a more general point, it is improves delivery of respirable particles. Two studies in

important to appreciate that interpretation of many acute severe asthma have shown an equivalent

studies in acute asthma is limited by their small sample bronchodilator response from salbutamol when given via

size, making them vulnerable to statistical type IT error, a holding chamber or a nebuliser, when the holding

although this may be overcome by meta-analysis where chamber used a six-fold lower nominal dose.7,8 Studies in

appropriate. acute asthma in children have shown a similar response to

terbutaline given by a nebuliser or by large-volume spacer

Bronchodilator therapy on a microgram equivalent or half microgram equivalent

The purpose of bronchodilator therapy in acute asthma is nominal basis.9J”

to reverse any bronchial smooth muscle spasm, in order to The delivery of salbutamol from large-volume spacer

buy time until the anti-inflammatory effect of the holding chambers may be impaired by multiple actuations

corticosteroid begins to work after 6-12 hours. In view of or inhalation delay,” suggesting that repeated cycles of

the severity of airflow obstruction, it is imperative to two puffs (200 ug) with a deep tidal breathing method

achieve a maximum or near maximum response with should be employed in acute asthma. General

minimum systemic adverse effects. High doses of inhaled practitioners should have a supply of large-volume plastic

P,-adrenoceptor agonists such as salbutamol are widely spacers which have been prewashed in detergent and drip-

accepted as first-line bronchodilator therapy, although the dried to reduce static charge. Use of a spacer in this way

role of the nebuliser for delivery has come under with up to ten sequential puff cycles of salbutamol (200

increasing scrutiny. The place of additional bronchodilator ug each time) will in most circumstances be equally or

therapy with inhaled anticholinergics and the use of more effective than an inadequately serviced compressor

intravenous salbutamol or aminophylline are debated. in conjunction with a low-performance nebuliser.

Improved lung delivery from a spacer might conceivably

inhaled p;agonist delivery increase systemic absorption, although this is likely to be

The nebuliser, administered by mask or mouthpiece and offset by reduced lung bioavailability due to reduced small

driven by an air compressor or more preferably by high- airway calibre in acute asthma, as well as down-regulation

flow oxygen, is the mainstay for delivering high doses of and associated desensitisation of extrapulmonary p,-

adrenoceptors. Further studies are required to look at

Lancet 1997; 350 (suppl II): 18-23 spacer use in patients with acute severe asthma.

Departments of Clinical Pharmacology and Respiratory Medicine, The main disadvantages of a spacer are that it precludes

Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, concomitant use of an oxygen mask (but not nasal

Dundee DDI 9SY, UK (B J Lipworth MD) cannula) and requires patient cooperation and closer

Vol350. Ocrober . 1997 ~1118

THE LANCET

i Pulse >IlO/min, respiratory rate >25/min j PaCO, >6kPa (45 mm Hg) 1

PEF ~60% predicted or best : [ PaO, <8kPa (60 mm Hg) j

j SaO, ~92% if. pH ~7.35 j

.. .,. . ..,. _ . _. “~. .^*-.-&

i Unable to complete sentences

.-. . . . _ --,

I Mf4Mxiiening features

i,~“-~I -_. ~.~.~-~-~

i Silent chest, cyanosis, feeble respiratory effort i

; Bradycardia or hypotension

i Exhaustion, confusion, or coma

PEF ~30% predicted or best

r.. -. ~. .._” . . - .” . _ Cr_ ._.^-_._“.“____llr

Initial treatment

“____ . ... 1 . .. -- ...I.- “. --.- 1 x

j { ‘&ygen’(at least 60% FiO,) Initial response $ Admit to hospital for I

! i Nebulised salbutamol (in 0,) +/- nebulised ipratropium’ within 1 h 1 further observation and 1

1j i5 Oral corticosteroid treatment

s .-.1-._“-.~ _.,.x.__i^l _. .. r .._.‘.... ,. .I a. ~, ..“.,~ _“,..” .F.,___ ii

Life-threatening features

or

Poor initial treatment response after 30 min

1

(repeat severity markers)

Add in

_. , I _,

Repeated nebulised salbutamol every 30 min

: Nebulised ipratropium

iv corticosteroid

Consider iv salbutamol or aminophylline

Chest radiograph to’exciude pne&n&horax

I Monitor serum K with high dose &-agonist

_I ., .

1 Poor response within 1 h

(repeat severity markers)

1

Admit to intensive care for possible intubation and

mechanical ventilation

..”

:““.

Figure 1: Guidelines for hospital treatment of acute severe asthma

Adapted from international and UK guidelines.‘,* Usual recommended doses In adults for acute severe asthma: nebulised salbutamol 5 mg, nebulised

ipratropium 0.5 mg; oral prednisolone 50 mg, intravenous (iv) hydrocortisone 200 mg; iv salbutamol 4 pg/kg, iv aminophylline 5 mg/kg (both as

infusions over 20 min).

supervision by the doctor administering the treatment. showed a greater than 10% increase in FEVl after the

Furthermore, there is a perception by many patients that second inhalation, compared with 13 out of 29 patients

a nebuliser represents high-technology therapy compared who showed less than a 10% change in FEV, at the same

with the simpler plastic spacer, which many asthmatics time point with the Nebuhaler. This is in keeping with the

will already be using for their inhaled corticosteroid observation that in acute asthma 98% of patients were

therapy. In patients with more severe asthma and able to generate sufficient inspiratory flow through a

respiratory failure, continuous administration of Turbuhaler, allowing a therapeutic dose of terbutaline to

P,-agonists may be easier via a nebuliser, particularly be delivered to the airways.‘” These findings are therefore

when anxiety impairs patient cooperation. It has been reassuring for patients using dry-powder inhaler devices,

shown that routine substitution of metered-dose aerosol although in the presence of tachypnoea the use of tidal

in conjunction with a spacer (Aerochamber) instead of breathing with a nebuliser or large-volume spacer would

nebulised P,-agonist therapy resulted in projected annual be preferable.

savings in one hospital amounting to US@33 OOO.‘* Full or partial ,$-agonists

How do portable dry-powder inhalers perform when There has been controversy about the possible harmful

given as repeated puffs by patients before the doctor’s effects of inhaled fenoterol (a full agonist) compared with

arrival? In a study of 62 patients with acute severe airflow salbutamol (a weaker partial agonist). In particular, case-

obstruction, delivery of terbutaline given by dry-powder control studies from New Zealand suggested a putative

inhaler (Turbuhaler) or metered-dose inhaler plus large- association between fenoterol use and asthma deaths,

volume spacer (Nebuhaler) was evaluated with two which was attributed to its greater cardiac toxicity in

sequential 2.5 mg doses given 15 minutes apart.” A 39% conjunction with effects of hypoxaemia.” However, a

and 57% increase in forced expiratory volume at 1 second more detailed analysis of risk factors suggests that the

(FEVJ with the Turbuhaler compared with a 16% and association between fenoterol and severe life-threatening

23% improvement with the Nebuhaler was seen for the asthma is explained by preferential prescribing to patients

two doses. 32 out of 33 patients with the Turbuhaler with more severe disease.16

~1119 Vol350. October. 1997

THE LANCET

Studies in stable asthmatics have shown that when continuous nebulised salbutamol in patients with more

fenoterol and salbutamol are administered on a severe airflow obstruction.27J8

microgram equivalent basis (from 100 ug to 4000 ug), The pharmacokinetic profile for high-dose nebulised

there is no difference in bronchodilator potency, whereas salbutamol shows that rapid absorption occurs from the

systemic potency for B2-adrenoceptor responses is greater lung reaching a peak concentration within 10 minutes of

with fenoterol.” In adequately oxygenated patients with inhalation.“’ It is therefore conceivable that appreciable

acute severe asthma and dose titration of fenoterol (up to systemic concentrations may in part contribute to the

3200 pg) or salbutamol (up to 1600 ug) given via a spacer bronchodilator effect. There is, however, considerable

(Aerochamber) with face mask, there was no evidence of interindividual variability in lung bioavailability of

clinically significant cardiac arrhythmias, despite the fact salbutamol when given by the nebulised route in acute

that the two-fold higher dose of fenoterol produced asthma, and a more predictable pharmacokinetic profile is

greater systemic B,-mediated effectsI In particular, with achieved with the intravenous route.30,31

respect to changes in QTc interval, less than 5% of Two large multicentre studies in acute severe asthma

patients had moderate prolongation (1525%) and none have compared treatment with either intravenous or

showed severe prolongation (>25%). nebulised salbutamo1.32’33 The intravenous salbutamol

Another property of a partial agonist such as regimens were administered either as a 10 minute bolus of

salbutamol is that it would be predicted from first 5 ugikg a1one,32 or as a 60 minute infusion of 500 ug in

principles to behave as a competitive antagonist at conjunction with hydrocortisone 200 mg.13 Both studies

B,-adrenoceptors in the presence of raised adrenergic showed a better bronchodilator response with the inhaled

tone, as has been demonstrated under experimental route. Higher plasma salbutamol concentrations were

conditions in healthy volunteers.‘” However, this found with the inhaled route in one study” and the

phenomenon is clinically unimportant in acute severe intravenous route in the other,33 and in both cases higher

asthma and there is no role for routinely using a higher levels were associated with greater systemic B,-mediated

efficacy agonist such as fenoterol instead of salbutamol. effects.

Salmeterol, which is a weaker agonist than salbutamol, The more relevant question-whether intravenous

also shows the same Bz-adrenoceptor antagonist effect in salbutamol improves the initial bronchodilator response

healthy vo1unteers.Z0 However, prior treatment with single when given in addition to nebulised salbutamol and

doses of salmeterol in stable asthmatic patients does not intravenous corticosteroid-has been addressed in two

appear to impair the bronchodilator response to repeated studies.‘4,35 In acute asthmatic adults, Cheong et al found

puffs of either salbutamol or fenoteroLZ’~** that intravenous salbutamol 12 ugimin over 4 hours after

an initial 5 mg dose of nebulised salbutamol and

intravenous hydrocortisone, resulted in a greater

Anticholinergics

improvement in peak flow than three successive nebulised

The rationale for the use of anticholinergic therapy is the

5 mg doses given over 2 hours, although tachycardia was

presence of increased airway vagal tone which may not be

more prominent in the intravenous gr0up.l” In a study of

overcome by treatment with high doses of inhaled

acute severe asthmatic children, a 10 minute single

&-agonists alone. More recent studies have tended to

intravenous infusion of salbutamol (15 ugikg) or saline

reveal conflicting results on the benefit of adding was given in the first 2 hours in addition to optimum

nebulised ipratropium to nebulised salbutamo1.23-26 The frequent nebulised salbutamol and intravenous

variability in results probably relates to the criteria for

hydrocortisone, with follow-up for 24 hours.35 The

patient selection, the small numbers of subjects in some recovery time to cessation of 30 minute administration of

studies, the dose and frequency of administered nebulised nebulised salbutamol was 4 hours for the intravenous

salbutamol, and the use of concomitant systemic group compared with 11.1 hours in controls, with

corticosteroid therapy. Although mean improvements in intravenous salbutamol also being associated with a lower

FEV, with ipratropium tend to be small, it is likely that dependency on medical oxygen and with discharge from

larger increases may occur in certain individuals with an the emergency department 9.7 hours earlier than the

exaggerated degree of cholinergic tone who may also have control group. Systemic Bz-mediated effects on plasma

impaired B,-adrenoceptor responsiveness. On the basis glucose and potassium did not differ between the two

that high-dose nebulised ipratropium bromide has few groups, although there was a higher proportion of tremor

systemic adverse effects, its use is advocated for patients at 2 hours in those who received intravenous salbutamol.

with life-threatening features or for those who do not Studies with intravenous aminophylline have also

respond to initial high-dose inhaled Bz-agonists, as revealed conflicting results as to whether there is

suggested by the recommended guidelines. improvement over and above the response to high-dose

inhaled B,-agonist and systemic corticosteroid.3”39 As with

Intravenous bronchodilator therapy other studies of second-line bronchodilator agents, the

The available drugs for intravenous bronchodilator variability and results can be explained by methodological

therapy are the Bz-agonists and theophyllines. For differences between studies. The acute therapeutic

salbutamol, the main disadvantage of the parenteral route bronchodilator response to intravenous aminophylline is

of administration is systemic B,-mediated adverse effects, dependent on achieving adequate blood concentrations

which are usually greater than those associated with the which requires monitoring, and its use is associated with

inhaled route. Nonetheless, it is conceivable in acute drug interactions and more frequent adverse effects than

severe asthma that greatly reduced peripheral airway other second-line agents such as nebulised ipratropium.

calibre would result in poor lung delivery when given by There is, therefore, no rationale for deviating from the

the inhaled route of administration. This effect can be recommended guidelines in terms of reserving the use of

partly offset by increasing the dose and frequency of the intravenous bronchodilator therapy as second-line

inhaled bronchodilator, as has been shown in studies of treatment except in life-threatening cases.

Vol350 * October - 1997 SII20

THE LANCET

airway concentration of corticosteroid with the inhaled

route, this may be negated by poor peripheral aerosol

delivery due to severe airway narrowing in an acute

attack. There are concerns that high-dose inhaled

corticosteroid might be inappropriately administered to

patients with acute asthma in whom the severity of the

attack has been underestimated. One possible

compromise might be to use high-dose systemic

corticosteroid in the first 24 to 48 hours, followed by

high-dose inhaled corticosteroid, providing that the

patient has responded adequately to initial therapy in

terms of a peak expiratory flow (PEF) above 60% of

predicted or best. However, the optimum duration of

systemic corticosteroid therapy and when to institute

inhaled corticosteroids remain unclear.

Preliminary data have shown that following initial

treatment with oral prednisolone and high-dose inhaled

/3,-agonist, recovery of lung function is similar after

7 days of follow-up treatment with budesonide 3200 ng

per day to a tapering dose of prednisolone from 40 mg to

5 mg daily.47 In another study, inhaled fluticasone

propionate 2000 ug per day was as effective as a 16-day

reducing course of oral prednisolone in patients with a

Figure 2: Acute bronchodilator response (FEV,) to cumulative mild exacerbation of asthma (PEF greater than 60%

doses of inhaled formoterol following pretreatment with regular predicted or best) who did not require hospital

formoterol 24 pg twice daily (FM) or placebo (PL) given for 4

admission.48 These data should not be extrapolated to

weeks

acute severe asthma (PEF less than 60% of predicted or

Repeated puffs of formoterol (12-108 ug, shown as shaded dose-ramp)

were given 1 hour after bolus administration of either systemic best), where the benefits of systemic corticosteroid far

corticosteroid (S) or placebo. The data are shown as change from outweigh any small potential risk of short-term systemic

baseline (A) in FEVI plotted against time after the first administered adverse effects.

puff of formoterol (time 0 represents 1 hour after placebo or steroid

administration). This shows that prior treatment with formoterol alone These types of studies looking at earlier sequential oral

(FM) induces bronchodilator subsensitivity, as a rightward shift in the and inhaled corticosteroid therapy in less severe acute

dose-response curve, compared with placebo alone (PL), which is asthma exacerbations have primarily been driven by the

acutely reversed after 1 hour of systemic corticosteroid administration

(FM+S). Adapted from Tan et al, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997,“’ with pharmaceutical industry. It is, therefore, important to bear

permission of the American Lung Association. in mind the relative drug costs, as for example in the

above study,“” where there was a 34-fold difference in

Corticosteroid therapy price for 2 weeks’ treatment with inhaled daily fluticasone

Systemic corticosteroids propionate 2000 ,ug (Flixotide, Allen and Hanbury’s, UK)

The rationale for the administration of systemic compared with daily oral prednisolone 25 mg (non-

corticosteroids in acute asthma is to reverse the proprietary).49 It should also be pointed out that high

inflammatory component which will not be ameliorated doses of inhaled corticosteroids may be associated with

by bronchodilator therapy. The efficacy of systemic systemic adverse effects,5o although these are unlikely to

corticosteroids is borne out by clinical experience and be of clinical relevance in the short-term. Thus, the

data from meta-analysis.4” Conventionally, corticosteroids common sense and safe approach to acute asthma is to

are administered systemically in acute asthma, although overtreat rather than undertreat, and as such all patients

there appears to be no gain in most patients for should receive systemic corticosteroid therapy as

intravenous over oral administration.4’a42 Although there is recommended by the guidelines.

evidence of a dose-response effect, there is little advantage

with doses of prednisolone greater than 50 mg daily in Facilitatory effects of corticosteroids on

adults.43,44 Dispersable prednisolone may be used as an P;adrenoceptors

alternative for patients who cannot swallow tablets whilst The acute bronchodilator response to repeated puffs

intravenous hydrocortisone or methylprednisolone should of inhaled P,-agonist may be attenuated in patients

be used for patients who are vomiting or in cases with life- receiving regular long-acting Pz-agonists such as

threatening features. In terms of disease control it has also salmeterol and formoterol. This occurs as a consequence

been shown that tapering a short pulse of oral of down-regulation and associated desensitisation of

corticosteroids is unnecessary after acute asthma Pz-adrenoceptors, due to receptor occupancy for 24

exacerbations provided that patients are also protected by hoursS1 Although studies in stable asthmatics have shown

concomitant inhaled corticosteroid therapy.45,46 However, only a small reduction in mean bronchodilator response,

the dose of prednisolone should be individually titrated there is considerable interindividual variability in

against the severity and recovery rate of the acute attack, susceptibility to desensitisation which appears to be

as part of a personalised self-management plan. associated with the Gly 16 polymorphism of the

PZ-adrenoceptor.52 Doctors and patients alike should

Inhaled corticosteroids therefore be alert to the possibility that higher doses of

Can the anti-inflammatory effect of oral corticosteroids be salbutamol might be required in an acute attack for

achieved by high doses of inhaled corticosteroid in acute patients receiving regular long-acting P,-agonists. In-vitro

asthma? Although one might expect a much higher local studies show that corticosteroids prevent Pz-agonist-

srr2 1 Vol350. October - 1997

THE LANCET

induced down-regulation and gene expression of 16 Garrett J, Lanes SF, Kolbe J, Rea HH. Risk of severe life threatening

pulmonary P2-adrenoceptors.53 Indeed it has been shown asthma and P-agonist type: an example of confounding by severity.

Thorax 1996; 51: 1093-99.

in stable asthmatics that intravenous hydrocortisone 200 17 Lipworth BJ, Newnham DM, Clark RA, Dhillon DP, Winter JH,

mg rapidly reverses bronchodilator desensitisation McDevitt DG. Comparison of the relative airways and systemic

induced by regular treatment with inhaled formoterol, potencies of inhaled fenoterol and salbutamol in asthmatic patients.

Thorax 1995; 50: 54-61.

and that this effect occurs within 1 hour of corticosteroid 18 Newhouse MT, Chapman KR, McCallum AL, et al. Cardiovascular

administratiorP (figure 2). Although there are no safety of high doses of inhaled fenoterol and albuterol in acute severe

comparable data in acute severe asthma, it is conceivable asthma. Chest 1996; 110: 595-603.

that P,-adrenoceptor down-regulation and desensitisation 19 Grove A, McFarlane LC, Lipworth BJ. Expr;ession of the

Pz-adrenoceptor partial agonist/antagonist activity of salbutamol in

would, if anything, be compounded by effects of excessive states of low and high adrenergic tone. Thorax 1995; 50: 134-38.

P,-agonist consumption. Thus corticosteroids may have a 20 Grove A, Lipworth BJ. Evaluation of the P,-adrenoceptor

dual effect in acute asthma with an early facilitatory effect agonist/antagonist activity of formoterol and salmeterol. Thorax 1996;

on airway Pz-adrenoceptor sensitivity and a later effect on 51: 54-58.

21 Smyth ET, I’avprd ID, Wang CS, Wisniewski AFZ, Williams J,

airway inflammation, which further emphasises the need Tattersfield AE. Interaction and dose equivalence of’salbutamol and

for corticosteroids to be administered as early as possible salmeterol in patients with asthma. BMJ 1993; 306: 54345.

during an acute asthma attack. 22 Grove A, Lipworth BJ. Effect of prior treatment with salmeterol and

formoterol on airway and systemic P,-responses to fenoterol. Thorax

1996; 51: 585-89.

Conclusions 23 O’Driscoll RB,Taylor RJ, Horsley MG, Chambers DK, Bernstein A.

The current international and national guidelines for the Nebulised salbutamol with and without ipratropium bromide in acute

treatment of acute asthma seem entirely appropriate in airflow obstruction. Lancet 1989; i: 1418-20.

recommending high-dose inhaled P,-agonist in 24 Schuh S, Johnson DW, Callahan S, Cally G, Levison H. Effects of

frequent nebulised ipratropium bromide added to frequent high dose

conjunction with systemic corticosteroid, and reserving albuterol therapy in severe childhood asthma. J Paediatr 1995; 126:

second-line therapy with ipratropium bromide or 63945.

intravenous bronchodilators for refractory or more severe 25 Karpel Jp, Schacter NE, Fanta C, et al. A comparison of ipratropium

cases. A greater awareness of the severity markers in acute and albuterol versus albuterol alone for the treatment of acute asthma.

Chest 1996; 110: 611-16.

asthma is also required, although when in doubt the safest 26 Fitzgerald MK, Grunfeld A, Parae I’D, et al. The clinical efficacy of

axiom is always to overtreat rather than undertreat to combination nebulised anticholinergic and adrenergic bronchodilators

prevent a potentially fatal attack. Further large-scale versus nebulised adrenergic bronchodilator alone in acute asthma.

Chest 1997; 111: 311-15.

studies are required to resolve issues such as the use of

27 Rudnitsky GS, Eberlein RS, Schoffstall JM, et al. Comparison of

large-volume spacers and the role of intravenous intermittent and continuously nebulised albuterol for treatment of

P,-agonists in acute severe asthma. asthma in an urban emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1993; 22:

1842-46.

28 Shrestha M, Bidadi K, Gourlay S, Heys J. Continuous versus

References intermittent albuterol at high and low doses in the treatment of severe

1 Global initiative for asthma: global strategy for asthma management aCute asthma in adults. Chest 1996; 110: 42-47.

and prevention. Bethesda: NIH, NHLBI, Publication No 95-3659, 29 Newt&am DM, Lipworth BJ. Nebuliser performance,

1995. pharmacokinetics, airways and systemic effects of salbutamol given via

2 The British guidelines on asthma management: 1995 review and a novel delivery system (Ventstream). Thorax 1994; 49: 762-70:

position statement. Thorax 1997; 52 (suppl 1): Sl-21. 30 Schuh S, Parkin I’, Rajan A, et al. High versus low dose frequently

3 Neville RG, Hoskins G, Smith B, Clark RA. How general practitioners administered nebulised albuterol in children with severe acute asthma.

manage acute asthma attacks. Thorax 1997; 52: 153-56. Paedianics 1989; 83: 513-18.

4 Lipwortb BJ, Jackson CM, Ziyaie D, Winter JH, Dhillon DP, 31 Janson C. Plasma levels and effects of salbutamol after inhaled or iv

Clark RA. An audit of acute asthma admissions to a respiratory unit. administration for stable asthma. Eur RespirJ 1991; 4: 544-50.

Health Bull 1992; 50: 389-98. 32 Swedish Society of Chest Medicine. High dose inhaled versus

5 Ferguson RJ, Stewart CM, Wathen CG, Moffat R, Crompton GK. intravenous salbutamol combined with theophylline in severe acute

Effectiveness of nebulised salbutamol administered in ambulances to asthma. Eur RespivJ 1990; 3: 163-70.

patients with severe acute asthma. Thorax 1995; 50: 81-82. 33 Salmeron S, Brochard L, Ma1 H, et al. Nebulised versus intravenous

6 Loffert DT, IkIe D, Nelson HS. A comparison of commercial jet albuterol in hypercapnic acute asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

nebulisers. Chest 1994; 106: 1788-93. 1994; 149: 1466-70.

7 Idris AH, McDermit MF, Raucci JC, Morrobel A, McGorray S, 34 Cheong B, Reynolds SR, Rajan G, Ward MJ. Intravenous P-agonist in

Hendels L. Emergency department treatment of severe asthma: severe acute asthma. BMJ 1988; 297: 448-50.

metered dose inhaler plus holding chamber is equivalent in 35 Browne GJ, Penna AS, Phung X, Soo M. Random&d vial of

effectiveness to nebuliser. Chest 1993; 103: 665-72. intravenous salbutamol in early management of acute severe asthma in

8 Colacone A, Afilalo M, Wokove N, Kreisman H. The comparison of children. Lancet 1997; 349: 301-05.

albuterol administered by metered dose inhaler and holding chamber 36 Murphy DG, McDermott MF, Rydman RJ, Sloan EP, Zalenski RJ.

or wet nebuliser in acute asthma. Chest 1993; 104: 835-41. Aminophylline in the treatment of acute asthma when P-adrenergics

9 Freelander M,Van Asperen PI? Nebuhaler versus nebuliser in children and steroids are provided. Arch Intern Med 1993; 153: 1784-88.

with acute asthma. BMJ 1984; 288: 1873-74. 37 Huang D, O’Brien RG, Harman E, et al. Does aminophylline benefit

10 Fuglasang G, I’edersen S. Comparison of nebuhaler and nebuliser adults admitted to the hospital in acute exacerbation of asthma. Ann

treatment of acute severe asthma in children. EurJ Respir Dis 1986; 69: Intern Med 1993; 119: 1155-60.

109-13. 38 DiGiulio G, Kercsmar C, Krug S, Alpert S, Marx C. Hospital

11 Clark DJ, Lipworth BJ. Effects of multiple actuations, delayed treatment of asthma: lack of benefit from theophylliie given in addition

inhalation and antistatic treatment on the lung bioavailability of to nebulised albuterol and intravenously administered corticosteroid. J

salbutamol via a spacer device. Thorax 1996; 51: 981-84. l’ediatr 1993; 122: 464-69.

12 Bowton DL, Goldsmith WM, Haponick EE Substitution of metered 39 Strauss ARE, Wertheim DL, Bonagura VR,Velacer DJ. Aminophylline

dose inhalers for hand held nebulisers: success and cost savings in a therapy does not improve outcome and increases adverse effects in

large acute care hospital. Chest 1992; 101: 305-08. children hospitalised with acute asthmatic exacerbations. Paediaaics

13 Tonnesen F, Laursen LC, EvaldT, Stahl E, IbsenTB. Bronchodilating 1994; 93: 205-10.

effective terbutaline powder in acute severe bronchial obstruction. 40 Rowe BH, Keller JL, Oxman AD. Effectiveness of steroid therapy in

Chest 1994; 105: 697-700. acute exacerbations of asthma: a meta-analysis. Am J Emevg Med 1992;

14 Brown PH, Ning ACWS, Greening Al’, McLean A, Crompton GK. 10: 301-10.

Peak inspiratory flow throughTurbuh&r in acute asthma. Eur RespirJ 41 Harrison BDW, StokesTC, Heart GJ,Vaughan DA, Ali MJ, Robinson

1995; 8: 1940-41. AA. Need for intravenous hydrocortisone in addition to oral

15 Crane J, Burgess C, Pearce NB, BlasleyY.The P-agonist controversy: a prednisolone in patients admitted to hospital with severe asthma

perspective. Eur Respir Rev 1993; 3: 475-82. without ventilatory failure. Lancet 1986; i: 181-84.

Vol350 * October * 1997 3122

THE LANCET

42 Rarto D, Alfaro C, Sipsey J, et al. Are intravenous corticosteroids 49 British National Formulary. London: British Medical Association and

required in status asthmaticus? JAMA 1988; 266: 527-29. Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain, 1997, no 33.

43 Webb JR. Dose of patients on oral corticosteroid treatment during 50 Lipworth BJ, Clark DJ. High-dose inhaled steroids in asthmatic

exacerbations of asthma. BMJ 1986; 292: 104547. children. Lancet 1996; 348: 820.

44 Bowler SD, Mitchel CA, Armstrong JG. Corticosteroids in acute severe 51 Grove A, Lipworth BJ. Bronchodilator subsensitivity to salbutamol

asthma: effectiveness of low doses. Thorax 1992; 47: 584-87. after twice daily salmeterol in asthmatic patients. Lancer 1995; 346:

45 O’Driscoll BR, Kalra S, Wilson M, Pickering CAC, Carroll KB, 201-06.

Woodcock AA. Double-blind trial of steroid tapering in acute asthma. 52 Tan KS, Hall II’, Dewar J, Dow E, Lipwortb BJ. Pz-adrenoccptor

Lancet 1993; 341: 324-27. polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to bronchodilator

46 Hatton MQF,Vatbenen AS, Allen MJ, Davies S, Cooke NJ. A desensitisation in moderately severe stable asthmatics. Lancet (in

comparison of abrupt stopping with tailing off oral corticosteroids in press).

acute asthma. Respir Med 1995; 89: 101-04. 53 Mak JCW, Nishikawa S, Shims&i H, Miyayasu I<, Barnes PJ.

47 Youngchaiyud l’, Maraneua N, Nana A, et al. Can inhaled steroids Protective effects of a glucocorticoid on down-regulation on

replace oral therapy after an acute asthma attack? Eur RespirJ 1996; pulmonary P,-adrenergic receptors in viva J Clin Invest 1995; 96:

9 (suppl23): 53s. 99-106.

48 Levy ML, Stevenson C, MalenT. Comparison of short courses of oral 54 Tan KS, Grove A, McLean A, GnosspeliusY, Hall Ii?, Lipwarth BJ.

prednisolone and fluticasone propionate in the treatment of adults with Systemic corticosteroid rapidly reverses bronchodilator subsensitivity

acute exacerbations of asthma in primary care. Thorczx 1996; 51: induced by formoterol in asthmatic patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

1087-92. 1997; 156: 28-35.

~123 Vol350 - October * 1997

You might also like

- Jurnal ALFIA NOFITASARI (200902027)Document7 pagesJurnal ALFIA NOFITASARI (200902027)Gede Kevin Adhitya SaputraNo ratings yet

- AnaesthesiaDocument4 pagesAnaesthesiaAglaube AirtonNo ratings yet

- Jerath2020 Article InhalationalVolatile-basedSedaDocument4 pagesJerath2020 Article InhalationalVolatile-basedSedasncr.gnyNo ratings yet

- ContentServer - 2022-02-07T120904.099Document8 pagesContentServer - 2022-02-07T120904.099Cesar Jesus Jara VargasNo ratings yet

- Falla VentilatoriaaaaaaaaDocument6 pagesFalla VentilatoriaaaaaaaaDIANA CAROLINA OTALORA ALVAREZNo ratings yet

- Ventilación Del Pulmón Sano CC Current 20Document5 pagesVentilación Del Pulmón Sano CC Current 20Silvia Lorena Mireles GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Acute Medicine Surgery - 2024 - Hoshino - Future Directions of Lung Protective Ventilation Strategies in AcuteDocument8 pagesAcute Medicine Surgery - 2024 - Hoshino - Future Directions of Lung Protective Ventilation Strategies in AcuteDiego AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Ards Prone PositionDocument9 pagesArds Prone PositionAnonymous XHK6FgHUNo ratings yet

- What Is New in Refractory Hypoxemia 2013Document4 pagesWhat Is New in Refractory Hypoxemia 2013EN BUNo ratings yet

- Asma NEJMDocument13 pagesAsma NEJMAlba RNo ratings yet

- CR Patho SummaryDocument22 pagesCR Patho SummaryDNAANo ratings yet

- Vibrating Mesh Nebulisers - Can Greater Drug DelivDocument11 pagesVibrating Mesh Nebulisers - Can Greater Drug DelivShabilah Novia SNo ratings yet

- Answer For McqsDocument3 pagesAnswer For Mcqseducare academy0% (1)

- Journal Reading STATUS ASMATIKUS-Rezky Amalia Basir 70700120013Document15 pagesJournal Reading STATUS ASMATIKUS-Rezky Amalia Basir 70700120013Rezky amalia basirNo ratings yet

- High-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy in Adults PDFDocument8 pagesHigh-Flow Nasal Cannula Oxygen Therapy in Adults PDFIda_Maryani94No ratings yet

- Newer Modes of Ventilation2Document9 pagesNewer Modes of Ventilation2Saradha PellatiNo ratings yet

- Chen 2015Document6 pagesChen 2015Manuel MesaNo ratings yet

- Alveolar Recruitment Maneuvers Under General AnesthesiaDocument12 pagesAlveolar Recruitment Maneuvers Under General AnesthesiaBetzaBarriosNo ratings yet

- Editorials: Assessing The Dose of Supplemental Oxygen: Let Us Compare MethodologiesDocument2 pagesEditorials: Assessing The Dose of Supplemental Oxygen: Let Us Compare MethodologiesJafar JilaniNo ratings yet

- HFNC Where Does It FitDocument4 pagesHFNC Where Does It FitTusar KoleNo ratings yet

- Jaa 4 001 PDFDocument12 pagesJaa 4 001 PDFRulianti BarantiNo ratings yet

- Lab 3. The Management ofDocument6 pagesLab 3. The Management ofMariana UngurNo ratings yet

- Advances in Acute Asthma: ReviewDocument5 pagesAdvances in Acute Asthma: ReviewKattia Pertuz MercadoNo ratings yet

- Von Goedecke Et Al 2004 Positive Pressure Versus Pressure Support Ventilation at Different Levels of Peep Using TheDocument5 pagesVon Goedecke Et Al 2004 Positive Pressure Versus Pressure Support Ventilation at Different Levels of Peep Using TheDr MunawarNo ratings yet

- Windisch 2002Document8 pagesWindisch 2002guidepNo ratings yet

- AARC Clinical Practice Guideline: Intermittent Positive Pressure Breathing-2003 Revision & UpdateDocument7 pagesAARC Clinical Practice Guideline: Intermittent Positive Pressure Breathing-2003 Revision & UpdategiiasNo ratings yet

- Asthma Beta PDFDocument8 pagesAsthma Beta PDFrosnita sidabalokNo ratings yet

- Whats New in Asthma and COPDDocument3 pagesWhats New in Asthma and COPDsobanNo ratings yet

- Grieco Et Al-2022-Intensive Care MedicineDocument4 pagesGrieco Et Al-2022-Intensive Care MedicineA. RaufNo ratings yet

- Anaesthsia SumaryDocument4 pagesAnaesthsia Sumarycn8jzdxjb6No ratings yet

- Acuterespiratorydistress Syndrome: Ventilator Management and Rescue TherapiesDocument16 pagesAcuterespiratorydistress Syndrome: Ventilator Management and Rescue TherapiessamuelNo ratings yet

- Oxygen Guideline Combined Final Published Version 22apr09sbDocument5 pagesOxygen Guideline Combined Final Published Version 22apr09sbليثNo ratings yet

- Chapter 29 B Mechanical Ventilation: Managing Ventilators SettingsDocument5 pagesChapter 29 B Mechanical Ventilation: Managing Ventilators SettingsElle ReyesNo ratings yet

- Should Patients With Mild Asthma Use Inhaled SteroidsDocument5 pagesShould Patients With Mild Asthma Use Inhaled Steroidstsiko111No ratings yet

- ARTventilacion Mecanica en EMDocument3 pagesARTventilacion Mecanica en EMNicole Ivette Arias RizikNo ratings yet

- Protective Ventilation of Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Review ArticleDocument10 pagesProtective Ventilation of Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Review ArticleshackeristNo ratings yet

- Low-Tidal-Volume Ventilation in The Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeDocument8 pagesLow-Tidal-Volume Ventilation in The Acute Respiratory Distress SyndromeJimmy Christianto SuryoNo ratings yet

- Ventilation in ARDS: Mechanical Ventilation For COVID-19Document13 pagesVentilation in ARDS: Mechanical Ventilation For COVID-19Praveen TagoreNo ratings yet

- RESP Failure in The ICU 2Document12 pagesRESP Failure in The ICU 2Keith SaccoNo ratings yet

- 2023 Setting PEEPDocument8 pages2023 Setting PEEPteranrobleswaltergabrielNo ratings yet

- ARDS ParalisisDocument7 pagesARDS ParalisisMarvin M. Vargas AlayoNo ratings yet

- Management of Life Threatening Asthma. Severe Asthma Series. CHEST 2022Document10 pagesManagement of Life Threatening Asthma. Severe Asthma Series. CHEST 2022carla jazmin cortes rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Anesthetics and Anesthesiology: Apneic Oxygenation and High FlowDocument7 pagesAnesthetics and Anesthesiology: Apneic Oxygenation and High FlowMuhammad SyamaniNo ratings yet

- HFCN IgdDocument6 pagesHFCN IgdayuniNo ratings yet

- Icu 3Document8 pagesIcu 3GemilleDaphneAndradaNo ratings yet

- Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Acute Respiratory Failure The Importance of The ValvexxxDocument8 pagesContinuous Positive Airway Pressure in Acute Respiratory Failure The Importance of The ValvexxxAaron G. TulayNo ratings yet

- Comment: Lancet Respir Med 2017Document2 pagesComment: Lancet Respir Med 2017Novy DitaNo ratings yet

- Management of Refractory Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument6 pagesManagement of Refractory Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseAnonymous ZUaUz1wwNo ratings yet

- J1-T4 CorticosteroidsDocument11 pagesJ1-T4 CorticosteroidsGoblin HunterNo ratings yet

- 271 High Frequency Jet VentilationDocument10 pages271 High Frequency Jet VentilationachyutsharmaNo ratings yet

- High Frequency Jet Ventilation Anaesthesia Tutorial of The Week 271Document10 pagesHigh Frequency Jet Ventilation Anaesthesia Tutorial of The Week 271anscstNo ratings yet

- Dysfunctional Lung AnatomyDocument7 pagesDysfunctional Lung AnatomyMoira SetiawanNo ratings yet

- 31274220: Advances in Non-Invasive Positive Airway Pressure TechnologyDocument11 pages31274220: Advances in Non-Invasive Positive Airway Pressure TechnologyLuis Enrique Caceres AlavrezNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia in Prehospital Emergencies and in The Emergency DepartmentDocument7 pagesAnesthesia in Prehospital Emergencies and in The Emergency DepartmentIvan TapiaNo ratings yet

- WeaningDocument9 pagesWeaningMonica Alejandra Estrada SorianoNo ratings yet

- Management of Life-Threatening Asthma (@ eDocument10 pagesManagement of Life-Threatening Asthma (@ eLex X PabloNo ratings yet

- Canmedaj01540 0049Document4 pagesCanmedaj01540 0049ImanNo ratings yet

- β Agonist Delivery by High-Flow Nasal Cannula During COPD ExacerbationDocument8 pagesβ Agonist Delivery by High-Flow Nasal Cannula During COPD Exacerbationttiger zhaoNo ratings yet

- Neonatal VentilationDocument65 pagesNeonatal VentilationBadr Chaban100% (5)

- Tuberculosis Leflet PKMDocument1 pageTuberculosis Leflet PKMYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- PDF Obgyn Borang - CompressDocument22 pagesPDF Obgyn Borang - CompressYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- Changes in Echocardiographic Parameters in Iron Deficiency Patients With Heart Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease Treated With Intravenous IronDocument10 pagesChanges in Echocardiographic Parameters in Iron Deficiency Patients With Heart Failure and Chronic Kidney Disease Treated With Intravenous IronYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- GRT 222 KuDocument7 pagesGRT 222 KuYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- See Editorial, P 151Document6 pagesSee Editorial, P 151Yan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- 304 Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy-4Document13 pages304 Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy-4anyNo ratings yet

- 304 Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy-4Document13 pages304 Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy-4anyNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Respi 1Document4 pagesJurnal Respi 1coolboyzoneNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Respi 1Document4 pagesJurnal Respi 1coolboyzoneNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Usia Dan Paritas Terhadap Kejadian Pre Eklampsia PDFDocument7 pagesPengaruh Usia Dan Paritas Terhadap Kejadian Pre Eklampsia PDFRadi PdNo ratings yet

- JNC8 HTNDocument2 pagesJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- PD Guidelines 2012Document36 pagesPD Guidelines 2012Yan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- Anesthetic Practices For Patients With Preeclampsia or HELLP Syndrome: A SurveyDocument6 pagesAnesthetic Practices For Patients With Preeclampsia or HELLP Syndrome: A SurveyYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Anestesi Regional Dan General Pada Sectio Cesaria Pada Ibu Dengan Pre Eklampsia Berat Terhadap Apgar ScoreDocument12 pagesPengaruh Anestesi Regional Dan General Pada Sectio Cesaria Pada Ibu Dengan Pre Eklampsia Berat Terhadap Apgar ScoreMuhamad Ongky NRahardiNo ratings yet

- Ventral Hernia PDFDocument8 pagesVentral Hernia PDFdianNo ratings yet

- IDF Diabetic Foot CPR 2017 FinalDocument70 pagesIDF Diabetic Foot CPR 2017 FinalHataitap ChonchepNo ratings yet

- Scalabrin1996 PDFDocument9 pagesScalabrin1996 PDFYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- Scalabrin1996 PDFDocument9 pagesScalabrin1996 PDFYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- Crystalloid Fluid Choice and Clinical Outcomes in Pediatric Sepsis J Peds 2017 PDFDocument17 pagesCrystalloid Fluid Choice and Clinical Outcomes in Pediatric Sepsis J Peds 2017 PDFYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- Metered Dose Inhaler With Spacer Versus Dry Powder Inhaler For Delivery of Salbutamol in Acute Exacerbations of Asthma: A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument7 pagesMetered Dose Inhaler With Spacer Versus Dry Powder Inhaler For Delivery of Salbutamol in Acute Exacerbations of Asthma: A Randomized Controlled TrialYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- Pattern of Hospital Admission and Outcome in Parkinson's Disease: A Study From Punjab, IndiaDocument7 pagesPattern of Hospital Admission and Outcome in Parkinson's Disease: A Study From Punjab, IndiaYan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- JPD Prepress/jpd 1 1 jpd181305/jpd 1 jpd181305Document7 pagesJPD Prepress/jpd 1 1 jpd181305/jpd 1 jpd181305Yan Hein TanawaniNo ratings yet

- 7081 - PHARMA - AnnualReport - 2001-12-31 - Pharma-OpsActivities-Achievements (795KB) - 583228015Document35 pages7081 - PHARMA - AnnualReport - 2001-12-31 - Pharma-OpsActivities-Achievements (795KB) - 583228015surayaNo ratings yet

- Drug Study PneumoniaDocument2 pagesDrug Study Pneumoniamadelaine_espirituNo ratings yet

- Ipratropium BromideDocument20 pagesIpratropium BromideAngelique Ramos PascuaNo ratings yet

- Respiratory System Pharmacology NotesDocument15 pagesRespiratory System Pharmacology NotesAli Rahimi100% (1)

- Drug Study IMDocument2 pagesDrug Study IMAbigail BrillantesNo ratings yet

- Emrgency Guidelines 3 RD EditionDocument123 pagesEmrgency Guidelines 3 RD EditionMitz MagtotoNo ratings yet

- Flowchart For AEBA Using Spacer - Revised 7-4-2020Document2 pagesFlowchart For AEBA Using Spacer - Revised 7-4-2020Noreen Ooi Zhi MinNo ratings yet

- Dental Management of AsthmaDocument8 pagesDental Management of AsthmaLorenzini GrantNo ratings yet

- Drugs Used in Bronchial Asthma & COPDDocument71 pagesDrugs Used in Bronchial Asthma & COPDShabnam Binte AlamNo ratings yet

- Pulmonary Function TestsDocument9 pagesPulmonary Function TestsRick Frea0% (1)

- Prepared By: Ulfat Amin MSC Pediatric NursingDocument25 pagesPrepared By: Ulfat Amin MSC Pediatric NursingAngelic khanNo ratings yet

- Emergency Medicine List PDFDocument46 pagesEmergency Medicine List PDFMohammedNo ratings yet

- Blue and White Illustrated Medical Healthcare in The 21st Century Education PresentationDocument15 pagesBlue and White Illustrated Medical Healthcare in The 21st Century Education PresentationLanz Andrei MatociñosNo ratings yet

- Lida AjocDocument10 pagesLida AjocEzra Knight Llesis AcebedoNo ratings yet

- Top-200-Drug ETSYDocument31 pagesTop-200-Drug ETSYBetsy Brown ByersmithNo ratings yet

- Pharmacological Management ofDocument9 pagesPharmacological Management ofAishah FarihaNo ratings yet

- AAH v2 Acute AsthmaDocument81 pagesAAH v2 Acute AsthmaEssa SmjNo ratings yet

- Pharma CasesDocument3 pagesPharma CasesVims BatchNo ratings yet

- BSC 2085 Anatomy and Physiology NCLEX Final Exam Predictor Study Guide (Verified and Correct Answers, 200 Questions Secure Highscore) Latest 2021Document131 pagesBSC 2085 Anatomy and Physiology NCLEX Final Exam Predictor Study Guide (Verified and Correct Answers, 200 Questions Secure Highscore) Latest 2021abbieNo ratings yet

- Tocolytic DrugDocument11 pagesTocolytic DrugWan Ahmad FaizFaizalNo ratings yet

- TOCOLYSIS IN VETERINARY REPRODUCTION-By:-Dr. DHIREN BHOIDocument47 pagesTOCOLYSIS IN VETERINARY REPRODUCTION-By:-Dr. DHIREN BHOIdrdhirenvet100% (2)

- CS4 Asthma Drug StudyDocument10 pagesCS4 Asthma Drug StudyAudrie Allyson GabalesNo ratings yet

- Feline Asthma: Laura A. Nafe, DVM, MS, Dacvim (Saim)Document5 pagesFeline Asthma: Laura A. Nafe, DVM, MS, Dacvim (Saim)Miruna ChiriacNo ratings yet

- Bronchodilators and Other Respiratory AgentsDocument61 pagesBronchodilators and Other Respiratory Agentsone_nd_onlyuNo ratings yet

- Drugs Affecting Respiratory SystemDocument65 pagesDrugs Affecting Respiratory SystemvivianNo ratings yet

- Dental Management of Medically Compromised PatientsDocument12 pagesDental Management of Medically Compromised Patientsمحمد ابوالمجدNo ratings yet

- Optimizing Acute Asthma Management During COVID-19 - V2Document34 pagesOptimizing Acute Asthma Management During COVID-19 - V2OKE channelNo ratings yet

- Autonomic Nervous System DrugsDocument128 pagesAutonomic Nervous System DrugsMubashra Habib100% (1)

- Albuterol DSDocument6 pagesAlbuterol DSFritz DecendarioNo ratings yet

- Salbutamol Drug StudyDocument2 pagesSalbutamol Drug StudyVinz Khyl G. CastillonNo ratings yet

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Self-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!From EverandSelf-Care for Autistic People: 100+ Ways to Recharge, De-Stress, and Unmask!Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Gut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)From EverandGut: The Inside Story of Our Body's Most Underrated Organ (Revised Edition)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (378)

- To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceFrom EverandTo Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern ScienceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (51)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)