Professional Documents

Culture Documents

In The Matter of The IBP Membership Dues Delinquency of Atty. MARCIAL A. EDILION - (3 20 2018) - PROSPER DELOS SANTOS

Uploaded by

joshuarus favorOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

In The Matter of The IBP Membership Dues Delinquency of Atty. MARCIAL A. EDILION - (3 20 2018) - PROSPER DELOS SANTOS

Uploaded by

joshuarus favorCopyright:

Available Formats

(GALING SA ETHICS NATIN DIGESTED BY ATE VANESSA)

(DINAGDAGAN KO LANG NANG RULLING NANG SC)

In the Matter of the IBP Membership Dues Delinquency of Atty. MARCIAL A. EDILION

(IBP Administrative Case No. MDD-1)

CONTENTION OF THE IBP: The respondent Marcial A. Edillon is a duly licensed practicing

Attorney in the Philippines. The IBP Board of Governors recommended to the Court the removal

of the name of the respondent from its Roll of Attorneys for stubborn refusal to pay

his membership dues assailing the provisions of the Rule of Court 139-A and the provisions of

par. 2, Section 24, Article III, of the IBP By-Laws pertaining to the organization of IBP, payment

of membership fee and suspension for failure to pay the same.

The authority of the IBP Board of Governors to recommend to the Supreme Court the removal of

a delinquent member's name from the Roll of Attorneys is found in par. 2 Section 24, Article Ill

of the IBP By-Laws (supra), whereas the authority of the Court to issue the order applied for is

found in Section 10 of the Court Rule, which reads:

SEC. 10. Effect of non-payment of dues. — Subject to the provisions of Section 12

of this Rule, default in the payment of annual dues for six months shall warrant

suspension of membership in the Integrated Bar, and default in such payment for

one year shall be a ground for the removal of the name of the delinquent member

from the Roll of Attorneys.

CONTENTION OF ATTY. EDILLON: Edillon contends that the stated provisions constitute

an invasion of his constitutional rights in the sense that he is being compelled as a pre-condition

to maintain his status as a lawyer in good standing, to be a member of the IBP and to pay the

corresponding dues, and that as a consequence of this compelled financial support of the said

organization to which he is admitted personally antagonistic, he is being deprived of the rights to

liberty and properly guaranteed to him by the Constitution. Hence, the respondent concludes the

above provisions of the Court Rule and of the IBP By-Laws are void and of no legal force and

effect.

RESOLUTION:

An "Integrated Bar" is a State-organized Bar, to which every lawyer must belong, as

distinguished from bar associations organized by individual lawyers themselves,

membership in which is voluntary. Integration of the Bar is essentially a process by which

every member of the Bar is afforded an opportunity to do his share in carrying out the objectives

of the Bar as well as obliged to bear his portion of its responsibilities. Organized by or under the

direction of the State, an integrated Bar is an official national body of which all lawyers are

required to be members. They are, therefore, subject to all the rules prescribed for the

governance of the Bar, including the requirement of payment of a reasonable annual fee for the

effective discharge of the purposes of the Bar, and adherence to a code of professional ethics or

professional responsibility breach of which constitutes sufficient reason for investigation by the

Bar and, upon proper cause appearing, a recommendation for discipline or disbarment of the

offending member. 2

The integration of the Philippine Bar was obviously dictated by overriding considerations of

public interest and public welfare to such an extent as more than constitutionally and legally

justifies the restrictions that integration imposes upon the personal interests and personal

convenience of individual lawyers. 3

Apropos to the above, it must be stressed that all legislation directing the integration of the Bar

have been uniformly and universally sustained as a valid exercise of the police power over an

important profession. The practice of law is not a vested right but a privilege, a privilege

moreover clothed with public interest because a lawyer owes substantial duties not only to his

client, but also to his brethren in the profession, to the courts, and to the nation, and takes part in

one of the most important functions of the State — the administration of justice — as an officer

of the court. The practice of law being clothed with public interest, the holder of this privilege

must submit to a degree of control for the common good, to the extent of the interest he has

created. As the U. S. Supreme Court through Mr. Justice Roberts explained, the expression

"affected with a public interest" is the equivalent of "subject to the exercise of the police power"

(Nebbia vs. New York, 291 U.S. 502).

The Integrated Bar is a State-organized Bar which every lawyer must be a member of as

distinguished from bar associations in which membership is merely optional and voluntary. All

lawyers are subject to comply with the rules prescribed for the governance of the Bar including

payment a reasonable annual fees as one of the requirements. The Rules of Court only compels

him to pay his annual dues and it is not in violation of his constitutional freedom to associate.

Bar integration does not compel the lawyer to associate with anyone. He is free to attend or not

the meeting of his Integrated Bar Chapter or vote or refuse to vote in its election as he chooses.

The only compulsion to which he is subjected is the payment of annual dues. The Supreme Court

in order to further the State’s legitimate interest in elevating the quality of professional legal

services, may require the cost of the regulatory program – the lawyers.

Such compulsion is justified as an exercise of the police power of the State. The right

to practice law before the courts of this country should be and is a matter subject to regulation

and inquiry. And if the power to impose the fee as a regulatory measure is recognize then a

penalty designed to enforce its payment is not void as unreasonable as arbitrary. Furthermore, the

Court has jurisdiction over matters of admission, suspension, disbarment, and reinstatement of

lawyers and their regulation as part of its inherent judicial functions and responsibilities thus the

court may compel all members of the Integrated Bar to pay their annual dues.

You might also like

- Dinner Theater Business PlanDocument21 pagesDinner Theater Business PlanBhumika KariaNo ratings yet

- In Re EdillonDocument2 pagesIn Re Edillonterrb1100% (11)

- 173089Document22 pages173089aiabbasi9615100% (1)

- 2016 BarDocument7 pages2016 BarJames CENo ratings yet

- Endencia and Jugo V DavidDocument2 pagesEndencia and Jugo V DavidEvelynBeaNo ratings yet

- Angara vs. Electoral CommissionDocument3 pagesAngara vs. Electoral CommissionMariano Acosta Landicho Jr.No ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-8848 Us V HartDocument2 pagesG.R. No. L-8848 Us V HartJOJI ROBEDILLONo ratings yet

- Bulacan v. Torcino (Digest, Legal Ethics)Document2 pagesBulacan v. Torcino (Digest, Legal Ethics)Nina ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics - CasesDocument369 pagesLegal Ethics - CasesLA AtorNo ratings yet

- Bongalon vs. PeopleDocument7 pagesBongalon vs. PeopleBeata Maria Juliard ESCANONo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 191002Document6 pagesG.R. No. 191002just wafflesNo ratings yet

- STATCON Chapter 3 Digested CasesDocument53 pagesSTATCON Chapter 3 Digested CasesSM BArNo ratings yet

- Eindencia Vs DavidDocument2 pagesEindencia Vs DavidI'm a Smart CatNo ratings yet

- Stat Con DigestDocument6 pagesStat Con DigestElla WeiNo ratings yet

- Cayetano Vs MonsodDocument2 pagesCayetano Vs MonsodDayanski B-mNo ratings yet

- Cayetano v. MonsodDocument1 pageCayetano v. MonsodEarnswell Pacina TanNo ratings yet

- Tolentino vs. Secretary of Finance PDFDocument4 pagesTolentino vs. Secretary of Finance PDFJona CalibusoNo ratings yet

- Norma de Joya Vs Jail Warden of Batangas CityDocument6 pagesNorma de Joya Vs Jail Warden of Batangas CityNatsirt Goin100% (1)

- FRANCIS V. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES G.R. No. 160261, November 10, 2003 PDFDocument4 pagesFRANCIS V. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES G.R. No. 160261, November 10, 2003 PDFShareable Media And PRNo ratings yet

- Arceta V Mangrobang GR 152895Document6 pagesArceta V Mangrobang GR 152895Dorothy PuguonNo ratings yet

- Montejo v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 118702, March 16, 1995.Document9 pagesMontejo v. COMELEC, G.R. No. 118702, March 16, 1995.Emerson NunezNo ratings yet

- Philo Law 2Document2 pagesPhilo Law 2Kirk LabowskiNo ratings yet

- Tanada VS AngaraDocument2 pagesTanada VS AngaraMae Clare D. BendoNo ratings yet

- Consti Digest CompleteDocument40 pagesConsti Digest CompleteJennica Gyrl G. DelfinNo ratings yet

- Notes On JavellanaDocument22 pagesNotes On JavellanaPatrice De CastroNo ratings yet

- Brion, Jr. vs. Brillantes, Jr. Admin Case No. 5305, March 17, 2003Document6 pagesBrion, Jr. vs. Brillantes, Jr. Admin Case No. 5305, March 17, 2003Ronald Jay GopezNo ratings yet

- Dimaporo v. Mitra, 202 SCRA 779Document7 pagesDimaporo v. Mitra, 202 SCRA 779Hann Faye BabaelNo ratings yet

- Max ShoopDocument3 pagesMax ShoopTommy DoncilaNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction CasesDocument19 pagesStatutory Construction CasesShiela BrownNo ratings yet

- C. State Immunity From Suit - Basis Constitutional and JurisprudenceDocument3 pagesC. State Immunity From Suit - Basis Constitutional and JurisprudenceLizanne GauranaNo ratings yet

- VARGAS CaseDocument5 pagesVARGAS CaseKim GuevarraNo ratings yet

- Alunan III Vs Mirasol 276 Scra 501Document7 pagesAlunan III Vs Mirasol 276 Scra 501Kevin KhoNo ratings yet

- Diao vs. MartinezDocument2 pagesDiao vs. Martinezroyel arabejoNo ratings yet

- Kuroda Vs JalanduniDocument1 pageKuroda Vs JalanduniGERALD DACILLONo ratings yet

- All AreasDocument648 pagesAll AreasGladys Morada100% (1)

- PACETE V COMM ON APPOINTEMENTSDocument2 pagesPACETE V COMM ON APPOINTEMENTSLloyd David P. VicedoNo ratings yet

- in Re Saturnino Bermudez, G.R. No. 76180Document2 pagesin Re Saturnino Bermudez, G.R. No. 76180Inez PadsNo ratings yet

- Legal Ethics Digest - Reyes Vs GubatanDocument1 pageLegal Ethics Digest - Reyes Vs GubatanPeter FrogosoNo ratings yet

- Bondoc Vs PinedaDocument2 pagesBondoc Vs PinedaFeBrluadoNo ratings yet

- Angara Vs Ver 97Document3 pagesAngara Vs Ver 97mrspotterNo ratings yet

- Jimenez v. VeranoDocument6 pagesJimenez v. VeranoTin SagmonNo ratings yet

- Cases For Separation of PowerDocument72 pagesCases For Separation of PowerMichael LagundiNo ratings yet

- Angara v. Electoral Commission 63 Phil 139Document1 pageAngara v. Electoral Commission 63 Phil 139Alma Adrias100% (1)

- Duque vs. COMELECDocument4 pagesDuque vs. COMELECTrisha Marie SungaNo ratings yet

- Indeterminate Sentence LawDocument4 pagesIndeterminate Sentence LawMark Gregory SalayaNo ratings yet

- Pascual v. BallesterosDocument2 pagesPascual v. BallesterosAnsai Claudine CaluganNo ratings yet

- Case Digests For SubmissionDocument18 pagesCase Digests For SubmissionAgatha GranadoNo ratings yet

- Vistan Vs NicolasDocument6 pagesVistan Vs NicolasChristopher Ronn PagcoNo ratings yet

- Garong VS. PEOPLEDocument13 pagesGarong VS. PEOPLEHestia VestaNo ratings yet

- Topic: Apportionment: Bagabuyo V. ComelecDocument2 pagesTopic: Apportionment: Bagabuyo V. ComelecRalph Deric Espiritu100% (1)

- Consti Cases Territory National Economy and PatrimonyDocument129 pagesConsti Cases Territory National Economy and PatrimonyJean Ben Go SingsonNo ratings yet

- Role of Lawyers in Legal EducationDocument13 pagesRole of Lawyers in Legal EducationAnimesh SinghNo ratings yet

- IBP vs. Zamora G.R. No.141284, August 15, 2000Document3 pagesIBP vs. Zamora G.R. No.141284, August 15, 2000meme bolongonNo ratings yet

- Cobb-Perez v. LantinDocument7 pagesCobb-Perez v. LantinN.V.No ratings yet

- Us vs. Valdez (G.r. No. L-16486Document2 pagesUs vs. Valdez (G.r. No. L-16486Elyka SataNo ratings yet

- Allunan Vs MirasolDocument2 pagesAllunan Vs Mirasolapril aranteNo ratings yet

- ETHICS Case#9 - Burbe vs. MagultaDocument1 pageETHICS Case#9 - Burbe vs. MagultaRio TolentinoNo ratings yet

- US V Ney & Bosque 1907Document2 pagesUS V Ney & Bosque 1907Benitez GheroldNo ratings yet

- In Re Atty EdillonDocument2 pagesIn Re Atty Edillonyannie11100% (1)

- PyioauebDocument161 pagesPyioauebgem baeNo ratings yet

- In Re EdillionDocument1 pageIn Re EdillionScribd ManNo ratings yet

- B.M. No. 1370 May 9, 2005 Letter of Atty. Cecilio Y. Arevalo, JR., Requesting Exemption From Payment of Ibp Dues. Decision Chico-Nazario, J.Document23 pagesB.M. No. 1370 May 9, 2005 Letter of Atty. Cecilio Y. Arevalo, JR., Requesting Exemption From Payment of Ibp Dues. Decision Chico-Nazario, J.Arexton H. AlunanNo ratings yet

- A Job InterviewDocument8 pagesA Job Interviewa.rodriguezmarcoNo ratings yet

- Uncertainty-Based Production Scheduling in Open Pit Mining: R. Dimitrakopoulos and S. RamazanDocument7 pagesUncertainty-Based Production Scheduling in Open Pit Mining: R. Dimitrakopoulos and S. RamazanClaudio AballayNo ratings yet

- Introduction To AccountingDocument36 pagesIntroduction To AccountingRajnikant PatelNo ratings yet

- Gears, Splines, and Serrations: Unit 24Document8 pagesGears, Splines, and Serrations: Unit 24Satish Dhandole100% (1)

- Standard C4C End User GuideDocument259 pagesStandard C4C End User GuideKanali PaariNo ratings yet

- Move It 3. Test U3Document2 pagesMove It 3. Test U3Fabian AmayaNo ratings yet

- Microfluidic and Paper-Based Devices: Recent Advances Noninvasive Tool For Disease Detection and DiagnosisDocument45 pagesMicrofluidic and Paper-Based Devices: Recent Advances Noninvasive Tool For Disease Detection and DiagnosisPatelki SoloNo ratings yet

- 580N 580SN 580SN WT 590SN With POWERSHUTTLE ELECTRICAL SCHEMATICDocument2 pages580N 580SN 580SN WT 590SN With POWERSHUTTLE ELECTRICAL SCHEMATICEl Perro100% (1)

- HDMI CABLES PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & TESTING REPORT #1 - 50FT 15M+ LENGTH CABLES v3 SMLDocument11 pagesHDMI CABLES PERFORMANCE EVALUATION & TESTING REPORT #1 - 50FT 15M+ LENGTH CABLES v3 SMLxojerax814No ratings yet

- MockboardexamDocument13 pagesMockboardexamJayke TanNo ratings yet

- AWS Migrate Resources To New RegionDocument23 pagesAWS Migrate Resources To New Regionsruthi raviNo ratings yet

- Cooling Gas Compressor: Cable ListDocument4 pagesCooling Gas Compressor: Cable ListHaitham YoussefNo ratings yet

- Question BankDocument42 pagesQuestion Bank02 - CM Ankita AdamNo ratings yet

- Python BarchartDocument34 pagesPython BarchartSeow Khaiwen KhaiwenNo ratings yet

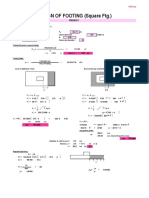

- Design of Footing (Square FTG.) : M Say, L 3.75Document2 pagesDesign of Footing (Square FTG.) : M Say, L 3.75victoriaNo ratings yet

- Autonics KRN1000 DatasheetDocument14 pagesAutonics KRN1000 DatasheetAditia Dwi SaputraNo ratings yet

- SC Circular Re BP 22 Docket FeeDocument2 pagesSC Circular Re BP 22 Docket FeeBenjamin HaysNo ratings yet

- NATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY v. CADocument11 pagesNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT COMPANY v. CAAndrei Anne PalomarNo ratings yet

- Bangalore University: Regulations, Scheme and SyllabusDocument40 pagesBangalore University: Regulations, Scheme and SyllabusYashaswiniPrashanthNo ratings yet

- WCN SyllabusDocument3 pagesWCN SyllabusSeshendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Blanko Permohonan VettingDocument1 pageBlanko Permohonan VettingTommyNo ratings yet

- Mosaic Charter School TIS Update 12202019Document73 pagesMosaic Charter School TIS Update 12202019Brandon AtchleyNo ratings yet

- SPI To I2C Using Altera MAX Series: Subscribe Send FeedbackDocument6 pagesSPI To I2C Using Altera MAX Series: Subscribe Send FeedbackVictor KnutsenbergerNo ratings yet

- 10.isca RJCS 2015 106Document5 pages10.isca RJCS 2015 106Touhid IslamNo ratings yet

- Frsky L9R ManualDocument1 pageFrsky L9R ManualAlicia GordonNo ratings yet

- ADocument2 pagesAẄâQâŗÂlïNo ratings yet

- Impact of Carding Segments On Quality of Card Sliver: Practical HintsDocument1 pageImpact of Carding Segments On Quality of Card Sliver: Practical HintsAqeel AhmedNo ratings yet

- Shubham Devnani DM21A61 FintechDocument7 pagesShubham Devnani DM21A61 FintechShubham DevnaniNo ratings yet