Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mindfulness Fulton PDF

Uploaded by

Maryam Khadiya Al YerrahiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mindfulness Fulton PDF

Uploaded by

Maryam Khadiya Al YerrahiCopyright:

Available Formats

Volume 38/N um ber 4/O ctober 2016/Pages 3 6 0 -3 7 4 /doi: 10 .17744/mehc.38.4.

06

Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and

C ounselor Characteristics and Session

Variables

Cheryl L. Fulton

Texas State University

Mindfulness has garnered interest as a counselor development tool for enhancing the therapeu

tic relationship and increasing counselor trainee effectiveness, yet empirical study o f counselor

mindfulness is limited. A study o f the relationship between mindfulness and client perceived

empathy among 55 client-counselor trainee dyads is reported. The relationships between coun

selor trainee mindfulness, self-compassion and ambiguity tolerance, experiential avoidance,

and session depth were also examined in this exploratory study. Counselor trainee mindfulness

was associated with client perceived empathy and both mindfulness and self-compassion were

associated with lower experiential avoidance and greater session depth as rated by the counselor

trainee. Self compassion was positively related to tolerance for ambiguity. Implications for

counselors, educators, and supervisors and suggestions for practical application o f mindfulness

for counselor development are discussed.

There are a number of counselor capabilities considered important to

effective counseling including empathy (Rogers, 1957), tolerance for ambigu

ity (Bien, 2004; Levitt & Jacques, 2005), and affect tolerance, also called expe

riential avoidance in its negative form (Bien, 2004; Fulton, 2005). Counselor

empathy is important to the development of the therapeutic relationship

(Rogers, 1957), working alliance (Trusty, Ng, & Watts, 2005), and counseling

outcomes (Elliott, Bohart, Watson, & Greenberg, 2011). Thus, empathic

ability is an essential counselor training outcome. Empathy, as a counseling

process, must first be experienced by the counselor, before it can be commu

nicated and, in turn, received by the client (Barrett-Lennard, 1981). Although

there are methods (e.g., microskills training) for teaching empathy skills (e.g.,

reflective listening), there are not equivalent methods for developing and main

taining one’s empathic capacity (e.g., Greason & Cashwell, 2009). Further,

anxiety, which is inherent in counselor training, can impede the ability for

empathy (Fliebert, Uhlemann, Marshall, & Lee, 1998).

Cheryl L. Fulton, D e p a rtm e n t o f Counseling, Leadership, A d u lt Education, and School Psychology, Texas

State University Correspondence concerning this a rticle should be addressed to: Cheryl L. Fulton, 601

University Dr., EDUC 4026, San Marcos. TX, 78666. E-m ail: clfu lto n @ tx s ta te .e d u .

360 0 Journal o f Mental Health Counseling

Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Session Variables

Affect tolerance and tolerance of ambiguity are purported to be important

to empathic ability and effective counseling (Bien, 2004; Fulton, 2005; Levitt

& Jacques, 2005). Bien (2004) proposed that tolerance of ambiguity be con

sidered an addendum to Roger’s (1957) necessary conditions for therapeutic

change because counselors must tolerate complex client situations without

pushing for a premature solution, becoming apathetic, or sharing in the client’s

despair. Ambiguity refers to being open to more than one interpretation, or

being uncertain (Levitt & Jacques, 2005). Ambiguous situations are those that

are complex, novel, and insoluble (conflicting information) and may promote

stress, avoidance, delay, suppression, or denial (McClain, 2009). Clients are

complex, often presenting contradictory feelings and concerns which can be

challenging, particularly for trainees and novice counselors (Borders & Brown,

2005); ambiguity can be a barrier to understanding and promote frustration

(McClain, 2009). Levitt and Jacques (2005) argued that ambiguity is inherent

in counseling and the training process itself, therefore, educators need methods

that support students to embrace ambiguity.

Experiential avoidance involves an unwillingness to remain in contact

with sensations, emotions, thoughts, even when doing so is unproductive

(Bond et ah, 2011). Experiential avoidance may be important to empathy as

counselors are confronted with clients’ painful emotions which they must be

present for, and empathize with, without personal distress, over-identification,

or avoidance (Bien, 2004; Rogers, 1957); this may be difficult for trainees newly

developing empathy skills. Further, because willingness to experience difficult

thoughts, feelings, and sensations is central to many theoretical approaches,

counselors must be able to model an appropriate relationship to these experi

ences (Bien, 2004). Bien (2004) recommended that counselors develop their

inner life through practices such as meditation; however, empirical support for

meditation as a means to develop affect tolerance among counselors is needed.

MINDFULNESS

Mindfulness has garnered attention as a potentially useful counselor train

ing tool, particularly with regard to the development and maintenance of coun

selor empathy and the therapeutic relationship (e.g., Buser, Buser, Peterson,

& Seraydarian, 2012; Fulton & Cashwell, 2015; Greason & Welfare, 2012).

Mindfulness, rooted in the Buddhist tradition, is defined as intentional present

moment awareness without judgment and requires an “affectionate attention”

(Kabat-Zinn, 2012, p. 53) achieved by bringing kindness, compassion, equa

nimity, patience, curiosity, and trust to one’s awareness (Kabat-Zinn, 1994).

Thus, mindfulness training typically includes both mindfulness practices that

produce awareness and insight, and loving-kindness and compassion practices

that foster compassion for both self and others. Self-compassion involves having

feelings of concern for one’s own suffering and approaching one’s shortcomings

with kindness, non-judgment, understanding, and awareness that shortcomings

are part of the common human experience (Neff, 2003). Scholars have been

uncertain as to whether compassion is considered an outcome of mindfulness

0 Journal of Mental Health Counseling 361

or a component of it (Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006). As

a result, researchers often include study of both mindfulness and self-compas

sion, as they can be differentially or synergistically related to outcome variables

such as empathy (Fulton & Cashwell, 2015).

Mindfulness, Self-compassion, and Empathy

Based on Buddhist psychology, empathy is viewed as a capacity that

can be cultivated through mental training, such as meditation (Greason &

Cashwell, 2009). Neff and Pommier (2013) found that experienced medita

tors scored higher on measures of compassion for humanity and empathic

concern than community or undergraduate samples. Based on controlled

neuroscientific studies, researchers found mindfulness practices affected neural

processes associated with enhanced empathic responses to social stimuli (Lutz,

Brefczynski-Lewis, Johnstone, & Davidson, 2008) and increased grey-matter

density in parts of the brain associated with empathy (Holzel et al., 2011).

Likewise, based on self-report, self-compassion has been associated with social

connection and empathy (Birnie, Speca, & Carlson, 2010; Neff, 2003).

Although sparse, there is evidence of a positive association between both

mindfulness and self-compassion and empathy among counselors based on

correlational studies (e.g., Fulton & Cashwell, 2015; Greason & Cashwell,

2009) and an early quasi-experimental study of mindfulness training among

counselor trainees (Lesh, 1970). These studies, however, were based on a

counselor’s self report of empathy. In a lone study, Greason and Welfare (2013)

found mindfulness was related to client rated therapeutic factors (e.g., positive

regard), however, it was not related to empathy. The researchers recommended

that data on the length of the counseling relationship be included in future

studies as this may have influenced the relationship between counselor mind

fulness and empathy in their study.

Mindfulness, Experiential Avoidance, and Tolerance for Ambiguity

Mindfulness-based interventions are designed to help individuals attend

to aversive stimuli, including sensations, cognitions, and emotions, with open,

non-reactive, non-judging, present-moment awareness (Baer, 2003). Bishop

et al. (2004) posited that acceptance during mindfulness practice leads to

decreased experiential avoidance and greater affect tolerance, coping, and

increased self-observation which, in turn, leads to greater emotional awareness

and cognitive complexity. Empirically, Farb et al. (2010) found that partic

ipants in an 8-week mindfulness training group (n = 18) had a similar sad

reaction to watching a sad film as a control group (n = 18), however, those with

mindfulness training had less neural activity (based on fMRI) while watching

the sad film than the control group and compared to baseline. The researchers

concluded that mindfulness meditation increased the ability to regulate emo

tion without necessarily avoiding or detaching from it. This has relevance for

counselor trainees who must learn to sense and be present for a client’s affec

tive state without becoming immersed in it (Rogers, 1957). Further, methods

362 0 Journal o f Mental Health Counseling

M i n d f u l n e s s , S e lf - C o m p a s s io n , a n d S e s s io n V a r ia b le s

aimed at reducing experiential avoidance such as acceptance and commitment

therapy incorporate mindfulness and have shown promise (Hayes, Luoma,

Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006), however, such approaches are designed for

client concerns, and there is little study of how mindfulness may relate to

experiential avoidance among counselors.

Tolerance of ambiguity is important, given the ambiguity' encountered

in counselor training as well as in client presentations (Bien, 2004; Levitt

& Jacques, 2005). Unfortunately, most studies of ambiguity tolerance in

counseling are decades old and yielded few results (Levitt & Jacques, 2005).

McClain (2009) created a new measure for ambiguity tolerance as he argued

that older measures were weak conceptually and psychometrically; thus, the

topic warrants reconsideration for study. Such studies are warranted, given that

ambiguity tolerance is considered important for counselor trainees (Levitt &

Jacques, 2005), and mindfulness is theorized to help individuals approach the

present moment with equanimity (Kabat-Zinn, 1994) so they can remain open

and flexible.

In sum, empathy, affect tolerance, and low experiential avoidance are

important training variables. Mindfulness may be a potential means to address

these variables, however, empirical study among counselors has been limited.

The goal of this study was to extend previous studies in several ways. First, study

of the relationship between counselor mindfulness and empathy among coun

selors has been based on counselor self report, and researchers have suggested

that client feedback about this relationship is an important next step (Fulton

& Cashwell, 2015; Greason & Cashwell, 2009). Further, Greason and Welfare

(2013) recommended obtaining data regarding the length of the counseling

relationship in future studies of counselor mindfulness and client perceived

empathy, as this may have limited their ability' to find a relationship between

counselor mindfulness and empathy in their study. Second, mindfulness out

comes such as affect tolerance and ambiguity tolerance have been theorized as

important counselor attributes and associated with mindfulness, however, no

current studies investigating these relationships among counselors were found.

Third, because of the potential role of self-compassion and mindfulness out

comes, I included study of the relationship between self-compassion and study

variables. Lastly, because there is limited knowledge of how counselor mind

fulness impacts a counseling session, for both client and counselor trainee,

session depth was examined. Session depth is the perceived power and value of

the counseling session and the counselor’s perceived effectiveness (Reynolds

et ah, 1996; Stiles & Snow, 1984). Fligher counselor- and client-rated session

depth have been associated with greater client return rate (Tryon, 1990) and

the perception that the session was a good vs. bad therapy hour (Reynolds et

ah, 1996). Because mindfulness involves greater attention and patience in the

present moment, it seems reasonable to explore its impact on both client-per

ceived empathy and session depth as session outcome variables.

The purpose of this study, therefore, was threefold: 1) to investigate the

relationship between counselor mindfulness (and its facets) and client per

ceived empathy; 2) to determine the relationship between mindfulness and

4 Journal o f M ental Health Counseling 363

self-compassion and counselor attributes, including affect and ambiguity toler

ance; and 3) to assess whether mindfulness and self-compassion are associated

with session dynamics (i.e., session depth) as rated by both the client and the

counselor. The following research questions were addressed: 1) Does mind

fulness have a significant relationship with client perceived empathy? Which

mindfulness facets best predict this relationship? 2) What are the respective

relationships between mindfulness, self-compassion, and session depth? 3)

What are the respective relationships between mindfulness and self-compas

sion and two counselor characteristics, experiential avoidance and ambiguity

tolerance? Concordantly, I hypothesized that 1) there would be a positive rela

tionship between mindfulness and client perceived empathy; no predictions

were advanced regarding which facet would be most impactful; 2) mindfulness

and self-compassion would be positively related to session depth (client and

trainee); and 3) mindfulness and self-compassion would be negatively related

to experiential avoidance and positively related to tolerance for ambiguity.

METHOD

Participants

Following institutional review board approval, a convenience sample of

master’s counseling students were recruited from practicum and intermediate

methods courses in a CACREP-accredited counseling program at the research

er’s university. Intermediate methods courses differ from practicum primarily

in that fewer clients are seen during the semester in the intermediate meth

ods courses. The researcher obtained faculty support for the study and they

agreed to have the researcher distribute and collect informed consent forms

and questionnaires during class as well as to have trainees invite one client to

participate. Eligible clients were university students and community members

seeking services at the program’s clinic who were 18 years of age or older and

able to voluntarily consent. Client-counselor trainee pairs participated in the

study after at least three sessions so a therapeutic relationship could be estab

lished before client-perceived empathy was assessed. A total of 59 students

from the total invited sample of 64 volunteered to participate yielding a 92%

response rate. Four surveys were not useable due to incomplete data.

Based on the total sample, 48 (87.3%) were women, and 7 (12.7%) were

men, with a mean age of 32.0 (SD = 7.3; Range = 23-50). Participants identi

fied as European American (n = 43, 78.3 %), Hispanic/Latino/a (n = 7, 12.7%),

and Biracial/Multiracial (n = 5, 9.0%). The majority of participants were in the

clinical mental health track (n = 27, 49.1%), followed by couple and family (n

= 12, 21.8%), school (n = 10, 18.2%), and dual track (n = 6, 10.9%). Seventy

percent were in practicum classes and 30% in intermediate methods classes.

Approximately 64.2% of trainees reported having a mindfulness practice, how

ever, their practice was primarily described as yoga, occurring less than weekly;

some meditation and prayer were also noted. Lastly, 39.6% of trainees reported

exposure to mindfulness education, primarily yoga classes, personal counsel

ing, or books. For client participants, 48 (87.3%) were women, and 7 (12.7%)

364 $ Journal o f Mental Health Counseling

M indfulness, Self-Com passion, and Session Variables

were men; client mean age was 36.4 (SD = 13.3; Range = 19-61). Participants

identified as European American (n = 34, 61.8%), Hispanic/Latino/a (n = 15,

27.2%), African American (n = 3,5.5%), and Biracial/Multiracial (n = 3,5.5%).

Procedure

Counselor trainees were provided with a script to read to their clients

inviting them to participate. The script included information that participation

was voluntary and in no way tied to receiving services and was followed with

obtaining client consent (100% of invited clients participated). Participants

were blind to the study variables and both clients and counselor trainees were

each given $3.00 as incentive for participation. Clients and trainees completed

surveys in separate rooms and the majority of clients turned in surveys directly

to the researcher as they exited the clinic. In the researcher’s absence, clients

returned surveys via sealed envelope to their counselor; these were in turn

collected by the instructor and returned to the researcher.

Instrumentation

Counselor trainees completed the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire

(FFMQ; Baer et ah, 2006), Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003), Session

Evaluation Questionnaire-Form 5 (SEQ; Stiles & Snow, 1984), Acceptance

and Action Questionnaire - II (AAQ-II; Bond, et ah, 2011), and Multiple

Stimulus Types Ambiguity Tolerance Scale-II (MSTATS; McClain, 2009).

Counselors also completed the Therapeutic Presence Inventory (Geller,

Greenberg, & Watson, 2010) which was used to answer research questions

not addressed in this article. Clients completed a demographics questionnaire,

tire SEQ, and the Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory-Client Form (BLRI;

Barrett-Lennard, 1962).

Mindfulness. The FFMQ (Baer et ah, 2006) is a 39-itenr self-report ques

tionnaire designed to measure mindfulness in daily life. The FFMQ consists

of five mindfulness facets (subscales): Observe, Describe, Act with Awareness,

Non-judge, and Non-react. Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1

(never or rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true) and each subscale is scored

and the five factors combined to form a total score of mindfulness. The FFMQ

has shown adequate construct validity and good internal consistency, with sub

scale alphas ranging from .75 to .91 and a full scale alpha of 0.96 (Baer et ah,

2006). The alpha coefficient in the current sample was .90 for the total scale

and ranged from .80 to .92 for subscales.

Session depth. The SEQ (Stiles & Snow, 1984) is a 21-item questionnaire

developed to measure client and counselor perspectives of immediate session

impact. Specifically, the SEQ measures whether a counseling session was

judged as good or bad based on two dimensions: 1) powerful and valuable ver

sus weak and worthless (session Depth) and 2) relaxed and comfortable versus

tense and distressing (session Smoothness). Two additional subscales measure

participants’ post session mood, Positivity and Arousal. Participants endorse

adjectives on a 7-point bipolar adjective format. The first 11 items measure

$ Journal o f Mental Health Counseling 365

session evaluation (depth and smoothness) using words such as “bad-good”

and “valuable-worthless”. Ten items measure post-session mood and include

adjectives such as “angr\’-pleased” and “calm-excited”. The authors reported

that factor-analytic studies confirmed all four dimensions as underlying coun

selor-client session ratings. Internal consistency was high (ranging from .81-.93)

for all dimensions across a variety of conditions and settings (Reynolds et al.,

1996). In this study, the independent dimension of session Depth was used to

evaluate participants’ most recent counseling session as this was deemed more

theoretically relevant to counselor mindfulness. Greater ability to attend to a

client’s experience should theoretically influence the client’s sense that the

session was valuable, however, it may not necessarily equate with the percep

tion that the session was relaxed. The alpha coefficient for session depth in the

current sample was .77 (counselor) and .68 (client).

C lient perceived empathy. The BLRI (Barrett-Lennard, 1962) comprises

four subscales: Level of Regard, Empathy, Unconditionality, and Congruence,

which are based on Rogers’s (1957) theory of the necessary conditions for

promoting therapeutic change in the counseling relationship. Clients rate the

extent to which they felt their counselor understood them in the session using

a 6-point scale (e.g., “My counselor nearly always knows exactly what I mean”).

Gurman (1977) reported that factor-analytic studies support the underlying

dimensions of the BLRI and that the mean internal consistency was high

(ranging from .74 - .91) across 14 studies. The Empathy subscale (16 items)

was utilized as a measure of client perceived empathy in the current study.

The alpha coefficient for the Empathy subscale was .75 for the study sample.

Self-compassion. Counselor trainees were given the 26-item SCS (Neff,

2003) which assesses positive and negative aspects of three components of

self-compassion: Self-Kindness (e.g., “I try to be loving towards myself when I’m

feeling emotional pain”) versus Self-Judgment (reverse-coded; e.g., “I’m disap

proving and judgmental about my own flaws and inadequacies”); Common

Humanity (e.g., “I try to see my failings as part of the human condition”) versus

Isolation (reverse-coded; e.g., “W hen I fail at something that’s important to me,

I tend to feel alone in my failure”); and Mindfulness (e.g., “W hen something

upsets me I try to keep my emotions in balance”) versus Over-Identification

(reverse-coded; e.g., “When something upsets me I get carried away with my

feelings”). Responses are given on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never)

to 5 (almost always). Neff and Germer (2012) suggested that the mindfulness

subscale of the SCS is distinct from general mindfulness (e.g., FFMQ) in two

ways. First, mindfulness as an aspect of self-compassion is narrower, referring

to awareness of negative thoughts and feelings associated with personal suf

fering as opposed to a full range of experience (positive, negative, or neutral)

with acceptance and equanimity. Second, mindfulness in self-compassion is

more person-focused than experience-focused. Neff (2003) found evidence of

adequate construct validity and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of

.92). In the current study, the alpha coefficient for the SCS was .94.

Experiential avoidance. The AAQ-II (Bond et al., 2011) is a seven-item

questionnaire used to measure psychological flexibility and experiential avoid-

366 $ Journal o f Mental Health Counseling

Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Session Variables

ance. Counselor trainees respond to a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (never true)

to 7 (always true) on items such as “I’m afraid of my feelings” and “Worries

get in the way of my success”. Bond, et al., (2011) found support for construct

validity and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of .88). In the current

study, the alpha coefficient for the AAQ-11 was .82.

Ambiguity tolerance. Counselor trainees were given the 13-item MSTATS

(McClain, 2009) which assesses ambiguity tolerance defined as an orientation

ranging from aversion to attraction, toward stimuli that are complex, unfa

miliar, and unsolvable. Responses are given on a 7-point scale ranging from

1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) on items such as “1 don’t tolerate

ambiguous situations well” and “I would rather avoid solving a problem that

must be viewed from several different perspectives”. McClain found support for

construct validity and high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of .83). In

this study the alpha coefficient was .88.

Demographics. Counselor trainees were queried about age, gender, race/

ethnicity, program track, field experience, meditation practice (and what type),

and exposure to mindfulness training in their counseling program (and what

type). Counselors also indicated the number of counseling sessions completed

at the time of the study. Clients were queried about age, gender, and race/

ethnicity.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

An a priori sample size (Soper, 2016) was calculated and 55 dyads were

deemed sufficient for a medium effect size of .3 (Cohen, 1988) and power of

.80 at the .05 level for F-tests for linear and multiple regressions. Preliminary

analysis of the data indicated that there were no outliers and data approximated

normal distributions for all instruments. Mean item replacement was used for

five items missing across the dataset.

Although the majority of students (70%) were in practicum classes, as

a preliminary analysis, the difference in mean scores for session related vari

ables (i.e., client perceived empathy and session depth) between students in

the practicum and intermediate methods courses were calculated to assess

whether developmental level would predict results. Based on f-tests, no statis

tically significant differences were found between practicum and intermediate

methods students for session related variables, thus students were combined

for analyses. However, a non-significant difference between practicum and

intermediate methods courses does not necessarily mean they are equivalent

(Weigold, Weigold, & Russell, 2013). Additionally, at least three completed

sessions were required to participate and the average number of sessions at the

data collection point was 6.0 (SD = 2.0; Range = 3-8). There was no signifi

cant relationship between client perceived empathy and session number (r =

.22, p = .11) possibly reducing the likelihood that more than the three mini

mum required sessions for participation impacted results for client perceived

empathy; however, it is still possible results may have been different with more

0 Journal of Mental Health Counseling 367

sessions. Lastly, there was concordance between client and counselor ratings

on session d e p th (r = .28, p = .04). Further, there was no significant difference

in counselor vs. client ratings of session depth (f = .86, d f = 108, p = .39) and

the effect size was small (C o h e n ’s d - .17).

Main Analyses

An alpha level of .05 was used for all main analyses. For research question

one, a Pearson product-moment correlation was used to test whether FFMO

was significantly and positively related to BLRI-Empathy and a multiple linear

regression analysis was used to explore which mindfulness facets most contrib

uted to the relationship. Overall FFMQ had a significant relationship with

BLRI-Empathy (r = .35, p = .01). Further, a model of the FFMQ facets had a

significant relationship with BLRI-Empathy (F(5, 49) = 2.82, p = .03) explain

ing 14.9% of the variance, however, Non-judge (b = .32, p = .03) was the only

facet significantly predictive of BLRI-Empathy (See Table 1).

For research question two, Pearson product-moment correlations were

used to test the hypotheses that FFMQ and SCS would each have a significant

negative relationship with a second session outcome variable, SEQ-Depth

(client and trainee). As predicted, both overall FFM Q (r = .37, p = .007) and

SCS (r = .37, p = .006) had a significant positive relationship with trainee SEQ-

Depth (coincidentally the same), however, unexpectedly, neither was related to

SEQ-Depth as rated by the client (See Table 2).

For research question three, Pearson product-moment correlations were

used to test the hypotheses that FFMQ and SCS would each have a significant

negative relationship with AAQ-II and a significant positive relationship with

MSTATS. As predicted, FFM Q (r = -.50, p < .001) and SCS (r = -.65, p < .001)

each had a strong and significant negative relationship with AAQ-II among

trainees. Interestingly, only SCS had a significant positive relationship with

MSTATS (r = .44, p = .001).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to explore the relationship between coun

selor trainee mindfulness and client’s perception of counselor empathy, as

Table I M u ltip le Regression o f M in d fu ln e s s Facets as P red ictors o f C lie n t Perceived E m p a th y

Variable B SE P t

Observe .26 .21 .19 1.21

Describe .38 .20 .25 1.90

Act with Awareness .14 .24 .09 .58

Non Judge .41 .19 .32 2.18*

Non React -.48 .31 -.25 -.1.54

* p < .05; A d j. R 2 = 14.9%

368 0 Journal o f M ental H e a lth C ou n se lin g

M in dfu ln e ss, Self-C om passion, a nd Session Variables

Table 2 Pearson Product-Moment Correlations for Study Variables

Variable SCS AAQ-II MSTAT BLRI SEQ-D-T SEQ-D-C

FFMQ .64 -.50 .20 .35 .37 .13

SCS - -.65 .44 .10 .37 .06

Note: *p < 0.05 level, **p < 0.0 1 level. FFMQ = Mindfulness; SCS = Self-Compassion; M Q - ll = Experiential

Avoidance, MSTAT= Ambiguity Tolerance; BLRI = Client Perceived Empathy; SEQ-D-T= Session Depth-Trainee;

SEQ-D-C = Session Depth-Client

well as how both counselor mindfulness and self-compassion were related

to counselor characteristics and session impact. Based on results, counselor

trainee self-report of mindfulness was directly related to clients’ perceptions

of counselor empathy. Further, both counselor self-reported mindfulness and

self-compassion were predictive of lower experiential avoidance and greater

session depth (counselor rated), however, only self-compassion was predictive

of greater ambiguity tolerance and neither was related to session depth as rated

by the client.

Finding that counselor mindfulness was related to client perceived empa

thy supports and extends studies in which mindfulness was related to empathy

based on counselor trainee self-report (Fulton & Cashwell, 2015; Greason &

Cashwell, 2009). Furthermore, length of the relationship was obtained and

data collected after three sessions to increase the likelihood of development of

the therapeutic relationship, which may explain the positive results for the cur-

Table 3 Instrum ent Means and Standard Deviations

Instrument M SD

Mindfulness Total 132.2 15.03

Observe 27.51 5.25

Describe 30.49 4.67

Act with Awareness 25.45 4.69

Non-judge 27.30 5.52

Non-react 21.45 3.62

Self-Compassion 13.91 2.51

Experiential Avoidance 19.11 5.58

Ambiguity Tolerance 53.23 11.10

Session Depth - 5.54 0.85

Session Depth - Client 5.69 1.00

Client Rated Empathy 77.60 7.00

Note: N = 55 pairs

^ Journal o f M ental H e a lth C ounseling 369

rent study as compared with a similar study by Greason and Welfare (2013) in

which length of the relationship was not assessed and no relationship between

counselor mindfulness and client-perceived empathy was found. Possibly

Greason and Welfare’s negative results were a consequence of assessing partici

pants who had not yet developed a therapeutic relationship with the counselor.

Non-judging of present moment experience was the one mindfulness facet

associated with client perceived empathy, however, no studies examining coun

selor mindfulness and empathy at the facet level were found for comparison.

Perhaps the ability to embrace one’s own experience without judgment aids

in the ability to be non-judging of others’ experience; understanding without

judgment is important to the therapeutic relationship (Rogers, 1957). Further,

the mindfulness facet non-judge was previously found to be negatively associ

ated with anxiety among counselors (Fulton & Cashwell, 2015). Anxiety can

impede the ability for counselor empathy (Hiebert et al., 1998) and self effi

cacy (Greason & Cashwell, 2009), therefore, it is possible that counselors with

higher mindfulness also had lower anxiety and greater counseling confidence,

which increased their capacity for empathy; further studies are needed to test

these relationships. Also, although facet analysis was possible, a larger sample

is warranted and may produce different findings.

Mindfulness-based interventions are designed to help individuals attend

to aversive sensations, cognitions, and emotions (Baer, 2003). In the current

study, both counselor mindfulness and self-compassion were strongly and

significantly related to lower experiential avoidance. As this study was the first

to explore mindfulness, self-compassion, and experiential avoidance among

counselors, there were no studies with which to directly compare results; how

ever, findings are consistent with a neuroscientific study in which mindfulness

training resulted in decreased experiential avoidance among a community

sample (Farb et al., 2010). It seems possible that if mindfulness and self-com

passion are associated with a greater ability to be in contact with one’s full

experience, counselors stronger in these abilities may be better able to model

such openness to experience for their clients. Future studies are needed to cor

roborate and extend findings from the current study to fully understand these

relationships.

Self- compassion was related to higher tolerance for ambiguity among the

study sample. It was surprising that mindfulness was not related to ambiguity

tolerance given that mindfulness training encourages an attitude of equanimity,

however, self-compassion focuses more directly on being gentle with one’s self

when confronted with difficult experiences and is negatively associated with

harsh self-judgment (Neff, 2003). Perhaps greater self-compassion enables

individuals to approach ambiguous situations more readily because they know

failure will not be met with self-criticism, but rather with self kindness.

Lastly, both mindfulness and self-compassion were associated with greater

session depth as evaluated by the couuselor only, even though counselor and

client rated depth were significantly related. This is similar to results obtained

by Daniel, Borders, and Willse (2015) who found that counselor mindfulness

was associated with session depth as rated by the supervisor, but not the super-

370 0 Journal o f Mental Health Counseling

M in d f u ln e s s , S e lf- C o m p a s s io n , a n d S e s s io n V a r ia b le s

visee. It seems both more mindful counselors and supervisors perceive greater

session depth than do their clients or supervisees. This may not be surprising

because sessions that involve collaborative engagement are associated with

higher ratings of depth, particularly by the counselor; although there is also

evidence that both counselor and client rated session depth is important to a

good counseling hour (Tryon, 1990).

Implications for Counselors, Educators, and Supervisors

Mindfulness has been associated with empathy based on client-perceived

empathy in the current study and previously with counselor trainee self-re

ported empathy (Fulton & Cashwell, 2015; Greason & Cashwell, 2009), devel

opment of the therapeutic relationship (Buser et ah, 2012), and positive client

outcomes (Grepnrair et ah, 2007). Taken together, there is growing evidence

that mindfulness training may be a useful method for developing qualities

important to an effective therapeutic relationship, and in turn, positive client

outcomes. Further, the mindfulness skill, non-judging present moment experi

ence, was most predictive of client-rated empathy. Activities (e.g., compassion

meditations) that enhance a counselor’s ability to maintain a non-judgmental

stance toward their own internal experience may be particularly apt for expe

riencing empathy toward a client. Randomized controlled studies of the effect

of mindfulness on non-judging within the counselor, and in turn, within the

counseling process, are needed to investigate this possibility.

Self-compassion was strongly associated with greater ambiguity tolerance

in the current study and has been associated with many other potential ben

efits to counselors such as less anxiety and emotional exhaustion (Birnie et

ah, 2010). Thus, incorporating self-compassion exercises into training and/

or supervision may be fruitful, particularly given the difficulty students have

coping with the ambiguity inherent in counselor training (Levitt & Jacques,

2005). Self-compassion practices may also be useful to counselor trainees as

tolerance for ambiguity is important to promoting deep exploration and change

during counseling (Bien, 2004). Both mindfulness and self-compassion were

strongly negatively associated with experiential avoidance in the current study.

Educators and trainees may find mindfulness worth exploring as a way to lower

experiential avoidance so that students can better tolerate the feelings and

thoughts that arise when confronted with the range of difficult emotions and

concerns expressed by clients and during the training process overall.

Mindfulness can be incorporated into counseling training and ongoing

development in a number of ways. For example, Hahn (1975) suggested that

mindfulness can be practiced informally, such as by taking a moment to focus

on the breath or giving any activity one’s full attention, in the present moment

without judgment or elaboration. Formal mindfulness practice involves an

“activity” used to cultivate mindfulness such as sitting meditation (Baer, 2003).

Both formal and informal practices could be incorporated into class or supervi

sion. Educators could also adapt the well-established mindfulness-based stress

reduction program (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 1990) for use across the curriculum,

0 Journal o f Mental Health Counseling 371

however, additional research is needed to determine the best timing and con

text for this training (e.g., supervision, class, practicum). MBSR courses are

readily available online and in-person so that any practicing counselor could

benefit from such training. Lastly, supervisors may encourage mindfulness and

self-compassion through modeling and skill-building (e.g., practice observing

one’s self without judgment or modeling self-compassion).

Limitations and Future Research

Results, while promising, need to be considered within the context of

limitations of the study design and sample. Participants were mostly female,

European American trainees from a single CACREP-accredited program;

results may not generalize to other programs, non-accredited programs, men,

or other ethnicities. A larger, more diverse sample is recommended for future

studies. Session data were based on trainees’ relationship with one client in one

session, limiting the range and variability of client responses. It is possible that

session depth may have been atypical, thus, researchers should consider collect

ing evaluative session data over several sessions. Additionally, all instruments

were self-report measures which can be influenced by degree of self-knowledge

and social desirability. Lastly, because this study was correlational, causation

cannot be determined. Randomized controlled studies designed to measure

specific changes as a result of mindfulness training are needed so educators

and supervisors can confidently use mindfulness training to improve counselor

performance and client outcomes.

In conclusion, despite the study limitations, the current study offers

support for the suggestion that both mindfulness and self-compassion are asso

ciated with important counselor variables such as client-perceived empathy,

affect tolerance, ambiguity tolerance, and session dynamics. Further studies are

needed to corroborate these findings and to further explore the role of affect

tolerance and tolerance for ambiguity in the counseling process. Ultimately,

if mindfulness is to be considered a useful counselor development method,

researchers must demonstrate that such training will improve counseling per

formance and client outcomes.

REFERENCES

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical

review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 125-143. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bpgO 15

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J.,&Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment

methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13, 27-45. doi: 10.1177/1073191105283504

Barrett-Lennard, G.T. (1981). The empathy cycle: Refinement of a nuclear concept. Journal of

Counseling Psychology, 28, 91-100. doi: 10.1037//0022-0167.28.2.91

Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1962). Dimensions of therapist response as causal factors in therapeutic

change. Psychological Monographs, 76(43). doi: 10.1037/h0093918

Bien, T. (2004). Quantum change and psychotherapy. Journal o f Clinical Psychologytin Session, 60,

493-501. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20003

372 0 Journal o f Mental Health Counseling

Mindfulness, Self-Compassion, and Session Variables

Birnie, K., Speca, M , & Carlson, L. E. (2010). Exploring self-compassion and empathy in

the context of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR). Stress and Health 26, 359-371.

doi: 10.1002/smi. 1305

Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N. D., Carmody, J., . . . Devins, G.

(2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and

Practice, 11, 230-241. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.bph077

Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K.,...Zettle, R.

D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire -

II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy,

42, 676-688. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

Borders, L. D., & Brown, L. L. (2005). The new handbook of counseling supervision. New York, NY:

Routledge.

Buser, T., Buser, J., Peterson, C. H., & Seraydarian, D. G. (2012). Influence of mindfulness

practice on counseling skill development. Journal of Preparation and Supervision, 4, 20-36.

doi:10.7729/41.0019

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

Daniel, L., Borders, L. D., & Willse, J. (2015). The role of supervisors’ and supervisees’ mindfulness

in clinical supervision. Counselor Education & Supervision, 54, 221-232. doi:10.1002/ceas.l2015

Elliott, R., Bohart, A. C., Watson, ]. C., & Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Empathy. Psychotherapy, 48,

43-49. doi:10.1037/a0022187

Farb, N. S., Anderson, A. K., Mayberg, H., Bean, ]., McKeon, D., & Segal, Z. V. (2010). Minding

one’s emotions: Mindfulness training alters the neural expression of sadness. Emotion, 10, 25-

33. doi: 10.1037/a0017151

Fulton, P. R. (2005). Mindfulness as clinical training. In C. K. Germer, R. D. Siegel, & P. R.

Fulton (Eds.), Mindfulness and psychotherapy (pp. 55-72). New York, NY: Guilford.

Fulton, C. L., & Cashwell, C. S. (2015). Mindfulness-based awareness and compassion: Predictors

of counselor empathy and anxiety. Counselor Education & Supervision, 54,122-133. doi: 10.1002/

ceas. 12009

Geller, S. M., Greenberg, L. S., & Watson, J. C. (2010). Therapist and client perceptions of

therapeutic presence: The development of a measure. Psychotherapy Research, 20, 599-610.

doi:10.1080/10503307.2010.495957

Greason, P. B., & Cashwell, C. S. (2009). Mindfulness and counseling self-efficacy: The

mediating role of attention and empathy. Counselor Education and Supervision, 49, 2-18.

doi: 10.1002/j. 15 56-6978.2009,tb00083.x

Greason, P. B., & Welfare, L. E. (2013). The impact of mindfulness and meditation practice on

client perceptions of common therapeutic factors. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 52, 235-

253. doi: 10.1002/j.2161-1939.2013.00045.x

Grepmair, L., Mitterlehner, F., Loew, T., Bachler, E., Rother, W., & Nickel, M. (2007). Promoting

mindfulness in psychotherapists in training influences the treatment results of their patients:

A randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 76, 332-338.

doi: 10.1159/000107560

Gurman, A. S. (1977). The patient’s perception of the therapeutic relationship. In A. S. Gurnman

& A. M. Razin (Eds.), Effective psychotherapy: A handbook of research (pp. 503-543). New York,

NY: Pergamon.

Hahn, T. N. (1975). Miracle of mindfulness. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and

commitment therapy: Model, processes, and outcomes. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44,

1-25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat,2005.06.006

Hiebert, B., Uhlemann, M. R., Marshall, A., & Lee, D. Y. (1998). The relationship between self

talk, anxiety, and counseling skill. Canadian Journal of Counseling, 32, 163-171.

Holzel, B. K., Carmody, J., Vangel, M., Congleton, C., Yerramsetti, S. M., Card, T., & Lazar, S. W.

(2011). Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry

Research: Neuroimaging, 191, 36-43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1990). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom o f your body and mind to face stress,

pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte.

0 Journal of Mental Health Counseling 373

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New

York, NY: Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2012). Mindfulness for beginners. Boulder, CO: Sounds True, Inc.

Lesh, T. (1970). Zen meditation and development of empathy in counselors. Journal of Humanistic

Psychology, 10, 39-74. doi: 10.1177/00221678700100010 5

Levitt, D. H., & Jacques, J. D. (2005). Promoting tolerance for ambiguity in counselor training

programs. Journal of Humanistic Counseling, Education and Development 44 46-54

doi: 10.1002/J.2164-490x.2005.tb0005 5.x

Lutz, A., Brefczynski-Lewis, J., Johnstone, 1., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Regulation of the neural

circuitry of emotion by compassion meditation: Effects of meditative expertise. PLoS ONE, 3,

1-10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001897

McClain, D. L. (2009). Evidence of the properties of an ambiguity tolerance measure: The

multiple stimulus types ambiguity tolerance scale-II (MSTAT-ll). Psychological Reports 105

975-988. doi: 10.2466/prO.105.3.975-988

Neff, K. D. (2003). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and

Identity, 2, 223-250. doi: 10.1080/15298860309027

Neff, K. D., & Germer, K. G. (2012). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of die Mindful

Self-Compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 28-44. doi: 10.1002/jclp. 2192 3

Neff, k., & Pommier, E. (2013). The relationship between self-compassion and other-focused

concern among college undergraduates, community adults, and practicing meditators. Self and

Identity, 12, 160-176. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2011.649546

Reynolds, S., Stiles, W. B„ Barkham, M., Shapiro, D. A., Hardy, G. E., & Rees, A. (1996).

Acceleration of changes in session impact during contrasting time-limited psychotherapies.

Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 577-586. doi: 10.1037/0022- 006X.64.3.577

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change.

Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21, 95-103. doi:10.1037/h0045357

Soper, D. (2016). Free statistics calculators (Version 4.0) [Software]. Available from http://www.

danielsoper.com/statcalc3/default.aspx.

Stiles, W. B., & Snow, J. S. (1984). Counseling session impact as viewed by novice counselors and

their clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 31, 3-12. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.31.1.3

Irusty, J., Ng, K., & Watts, R. E. (2005). Model of effects of adult attachment on emotional

empathy of counseling students. Journal of Counseling 6 Development, 83, 66-77.

doi: 10.1002/j. 15 56-6678.2005.tb00581.x

Tryon, G. S. (1990). Session depth and smoothness in relation to the concept of engagement in

counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 37, 248-253. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.37.3.248

Weigold, A., Weigold, I. K., & Russell, E. ]. (2013). Examination of the equival ence of self-report

survey-based papcr-and-pencil and Internet data collection methods. Psychological Methods 18

53-70. doi: 10.1037/a0031607

374 0 Journal o f Mental Health Counseling

Copyright of Journal of Mental Health Counseling is the property of American Mental Health

Counselors Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or

posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users

may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Personhood of Counsellor in CounsellingDocument9 pagesPersonhood of Counsellor in CounsellingPrerna singhNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Attachment Theory in Practice: Unveiling the Power of Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for Individuals, Couples, and Families.From EverandIntroduction to Attachment Theory in Practice: Unveiling the Power of Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) for Individuals, Couples, and Families.No ratings yet

- Mindfulness MattersDocument9 pagesMindfulness MattersumifNo ratings yet

- Development and standardization of a tool for assessing spirituality in families for family-based interventionsFrom EverandDevelopment and standardization of a tool for assessing spirituality in families for family-based interventionsNo ratings yet

- A Patient’S Guide to Psychotherapy: And an Overview for Students and Beginning TherapistsFrom EverandA Patient’S Guide to Psychotherapy: And an Overview for Students and Beginning TherapistsNo ratings yet

- Client Attachment To TherapistDocument11 pagesClient Attachment To Therapistjherrero22100% (2)

- Terapia Psicologica Negli AdultiDocument13 pagesTerapia Psicologica Negli Adultigrassochiara14No ratings yet

- Implicit or Explicit Compassion? Effects of Compassion Cultivation Training and Comparison With Mindfulness-Based Stress ReductionDocument32 pagesImplicit or Explicit Compassion? Effects of Compassion Cultivation Training and Comparison With Mindfulness-Based Stress ReductionGABRIELNo ratings yet

- Punihani CFDocument45 pagesPunihani CFGeeth MehtaNo ratings yet

- Substance Abuse Group Therapy Activities for Adults: A Complete Guide with over 800 Exercises and Examples for Effective Recovery and HealingFrom EverandSubstance Abuse Group Therapy Activities for Adults: A Complete Guide with over 800 Exercises and Examples for Effective Recovery and HealingNo ratings yet

- Mindfulness, Psychological Flexibility, and Counseling Self-Efficacy: Hindering Self - Focused Attention As A MediatorDocument25 pagesMindfulness, Psychological Flexibility, and Counseling Self-Efficacy: Hindering Self - Focused Attention As A MediatorShuhaidi AbusemanNo ratings yet

- Compassion Meditation, Therapist EmpathyDocument9 pagesCompassion Meditation, Therapist EmpathyMaria GemescuNo ratings yet

- Rapid Core Healing Pathways to Growth and Emotional Healing :: Using the Unique Dual approach of Family Constellations and Emotional Mind Integration for personal and systemic healthFrom EverandRapid Core Healing Pathways to Growth and Emotional Healing :: Using the Unique Dual approach of Family Constellations and Emotional Mind Integration for personal and systemic healthNo ratings yet

- Conferencia Dr. CondonDocument5 pagesConferencia Dr. CondonAlexa Yakeline MenesesNo ratings yet

- Papt 12333Document14 pagesPapt 12333Noor BahrNo ratings yet

- UseAttmntTheo AdultPsychotherapyDocument14 pagesUseAttmntTheo AdultPsychotherapyVro AlfrzNo ratings yet

- Person-Centered and Existential Therapy ApproachesDocument9 pagesPerson-Centered and Existential Therapy ApproachesRas Jemoh100% (1)

- Compassion and Forgiveness - Based Intervention Program On Enhancing The Subjective Well-Being of Filipino Counselors: A Quasi-Experimental StudyDocument24 pagesCompassion and Forgiveness - Based Intervention Program On Enhancing The Subjective Well-Being of Filipino Counselors: A Quasi-Experimental StudyAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Neff Et Al-2013-Journal of Clinical PsychologyDocument17 pagesNeff Et Al-2013-Journal of Clinical PsychologyANANo ratings yet

- DBT Workbook For Clinicians-The DBT Clinician's Guide to Holistic Healing, Integrating Mind, Body, and Emotion: The Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Skills Workbook for Holistic Therapists.From EverandDBT Workbook For Clinicians-The DBT Clinician's Guide to Holistic Healing, Integrating Mind, Body, and Emotion: The Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Skills Workbook for Holistic Therapists.No ratings yet

- Examining Conditions For Empathy in Counseling: An Exploratory ModelDocument22 pagesExamining Conditions For Empathy in Counseling: An Exploratory ModelDeAn WhiteNo ratings yet

- Developing Self Compassion As A Resource For Coping With Hardship: Exploring The Potential of Compassion Focused TherapyDocument14 pagesDeveloping Self Compassion As A Resource For Coping With Hardship: Exploring The Potential of Compassion Focused TherapyShandy PutraNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Group Therapy Activities for Adults: A Complete Guide to Building Resilience and Fostering Wellness through Collaborative Therapeutic StrategiesFrom EverandMental Health Group Therapy Activities for Adults: A Complete Guide to Building Resilience and Fostering Wellness through Collaborative Therapeutic StrategiesNo ratings yet

- Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy Using Articulated DisputationFrom EverandRational Emotive Behavior Therapy Using Articulated DisputationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Spiritual Assessment in Social Work and Mental Health PracticeFrom EverandSpiritual Assessment in Social Work and Mental Health PracticeNo ratings yet

- Ritchie Bryant 2012 IJW Pos MindfulnessDocument32 pagesRitchie Bryant 2012 IJW Pos MindfulnessSanjana LvNo ratings yet

- Vi Research Proposal Outline 26 June 2019Document6 pagesVi Research Proposal Outline 26 June 2019ninaNo ratings yet

- LKM On Empathy For Counselling StudentsDocument10 pagesLKM On Empathy For Counselling StudentsM DIVYA BHARATHINo ratings yet

- The Power of Shared Experiences: Peer-to-Peer Insights on Mental Health: Life Skills TTP The Turning Point, #3From EverandThe Power of Shared Experiences: Peer-to-Peer Insights on Mental Health: Life Skills TTP The Turning Point, #3No ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Practices for Christian Counseling and PsychotherapyFrom EverandEvidence-Based Practices for Christian Counseling and PsychotherapyNo ratings yet

- 03 Mechanism of Changes and Techniques of PsychotherapiesDocument17 pages03 Mechanism of Changes and Techniques of PsychotherapiesKeya BhattNo ratings yet

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy for Wellness and Recovery: Interventions and Activities for Diverse Client NeedsFrom EverandDialectical Behavior Therapy for Wellness and Recovery: Interventions and Activities for Diverse Client NeedsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Adult Attachment, Shame, Depression, and Loneliness: The Mediation Role of Basic Psychological Needs SatisfactionDocument11 pagesAdult Attachment, Shame, Depression, and Loneliness: The Mediation Role of Basic Psychological Needs SatisfactionAnonymous TLQn9SoRRbNo ratings yet

- Research On HellingerDocument23 pagesResearch On Hellingerprem10167% (3)

- Williams Integrative PaperDocument18 pagesWilliams Integrative Paperapi-231978749No ratings yet

- Emotionally Focused Therapy For CouplesDocument8 pagesEmotionally Focused Therapy For Couplessingernora100% (1)

- 2018 A Feminist Qualitative Investigation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Group As Context For Fostering Intrapersonal Growth - Molly StehnDocument32 pages2018 A Feminist Qualitative Investigation of Dialectical Behavior Therapy Skills Group As Context For Fostering Intrapersonal Growth - Molly StehnFabián MaeroNo ratings yet

- Advanced Empathy A Key To Supporting People Experiencing Psychosis or Other Extreme StatesDocument18 pagesAdvanced Empathy A Key To Supporting People Experiencing Psychosis or Other Extreme StatesMichelle KellyNo ratings yet

- Apego Adulto Inseguro y Procesos Narrativos en PsicoterapiaDocument15 pagesApego Adulto Inseguro y Procesos Narrativos en PsicoterapiaJoseNo ratings yet

- Learning from the Unconscious: Psychoanalytic Approaches in Educational PsychologyFrom EverandLearning from the Unconscious: Psychoanalytic Approaches in Educational PsychologyNo ratings yet

- Model of Effects of Adult Attachment On Emotional Empathy of Counseling StudentsDocument13 pagesModel of Effects of Adult Attachment On Emotional Empathy of Counseling Studentsomair.latifNo ratings yet

- CBT+ DBT+ACT & Beyond: A Comprehensive Collection on Modern Therapies Including PTSD Healing, Vagus Nerve Insights, Polyvagal Dynamics, EMDR Techniques, and Somatic ApproachesFrom EverandCBT+ DBT+ACT & Beyond: A Comprehensive Collection on Modern Therapies Including PTSD Healing, Vagus Nerve Insights, Polyvagal Dynamics, EMDR Techniques, and Somatic ApproachesNo ratings yet

- 01 - Counselling and Psychotherapy Is There Any DifferenceDocument8 pages01 - Counselling and Psychotherapy Is There Any Differenceally natashaNo ratings yet

- From Isolation to Connection: A Practical Guide to Building and Maintaining Fulfilling FriendshipsFrom EverandFrom Isolation to Connection: A Practical Guide to Building and Maintaining Fulfilling FriendshipsNo ratings yet

- Cou 56 4 549Document15 pagesCou 56 4 549veralynn35No ratings yet

- DefinitionDocument5 pagesDefinitionEmma TaylorNo ratings yet

- Volunteers Emotional Well Being PMJ AAM Nov 21Document28 pagesVolunteers Emotional Well Being PMJ AAM Nov 21Harikrishnan KmNo ratings yet

- Therapist Variables-PopescuDocument17 pagesTherapist Variables-PopescuAnisha DhingraNo ratings yet

- Journal of Fluency Disorders: Alanna Lindsay, Marilyn LangevinDocument12 pagesJournal of Fluency Disorders: Alanna Lindsay, Marilyn LangevinYenifer Bravo CarrascoNo ratings yet

- CBT EducationalDocument19 pagesCBT EducationalNASC8No ratings yet

- Clinical FormulationDocument24 pagesClinical Formulationaimee2oo8100% (2)

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide to DBT and Using Behavioral Therapy to Manage Borderline Personality DisorderFrom EverandDialectical Behavior Therapy: A Comprehensive Guide to DBT and Using Behavioral Therapy to Manage Borderline Personality DisorderNo ratings yet

- Theory of Interpersonal RelationsDocument12 pagesTheory of Interpersonal RelationsjebashanthiniNo ratings yet

- Principles of Intensive PsychotherapyFrom EverandPrinciples of Intensive PsychotherapyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Artigo 11Document9 pagesArtigo 11Kariane RoscocheNo ratings yet

- Emotional Regulation and Interpersonal Effectiveness As Mechanisms of Change For Treatment Outcomes Within A DBT Program For AdolescentsDocument13 pagesEmotional Regulation and Interpersonal Effectiveness As Mechanisms of Change For Treatment Outcomes Within A DBT Program For AdolescentsLauraLoaizaNo ratings yet

- Fostering Self Awareness in Novice Therapists Using Internal Family Systems TherapyDocument13 pagesFostering Self Awareness in Novice Therapists Using Internal Family Systems TherapySindhura TammanaNo ratings yet

- Historia OtomanaDocument38 pagesHistoria OtomanaMaryam Khadiya Al YerrahiNo ratings yet

- Art of Arabic Calligraphy PDFDocument5 pagesArt of Arabic Calligraphy PDFMaryam Khadiya Al YerrahiNo ratings yet

- The Sufi Concept of DreamsDocument12 pagesThe Sufi Concept of DreamsMaryam Khadiya Al YerrahiNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Sufism On Traditional Persian Music (Seyyed Hossein Nasr) PDFDocument13 pagesThe Influence of Sufism On Traditional Persian Music (Seyyed Hossein Nasr) PDFIsraelNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Spatial DataDocument10 pagesCharacteristics of Spatial DataSohit AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Writing Assignment 3Document5 pagesWriting Assignment 3api-454037345No ratings yet

- Soal English Usbn 19Document8 pagesSoal English Usbn 19Gina Inayatul MaulaNo ratings yet

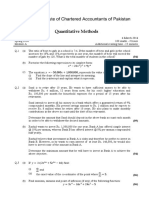

- Quantitative Methods Exam Focuses on Statistical AnalysisDocument3 pagesQuantitative Methods Exam Focuses on Statistical Analysissecret studentNo ratings yet

- EE 587 SoC Design & Test Methodologies, Yield AnalysisDocument30 pagesEE 587 SoC Design & Test Methodologies, Yield AnalysissanthiyadevNo ratings yet

- Eee 2018Document4 pagesEee 2018kesavantNo ratings yet

- BST Chapter 1 Management QuestionsDocument2 pagesBST Chapter 1 Management QuestionsJeegar BhattNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Natural and Social SciencesDocument4 pagesDifference Between Natural and Social SciencesRica VilladarezNo ratings yet

- Role of Advertising in FMCG SectorDocument81 pagesRole of Advertising in FMCG SectorSami ZamaNo ratings yet

- Pyl 100: Tutorial Sheet #2 (Supplement) : Xia Kiixiya Kiiia B IkDocument1 pagePyl 100: Tutorial Sheet #2 (Supplement) : Xia Kiixiya Kiiia B IkChethan A RNo ratings yet

- Itala D'Ottavianno - Translations Between LogicsDocument6 pagesItala D'Ottavianno - Translations Between LogicsKherian GracherNo ratings yet

- DirectX TutorialDocument128 pagesDirectX Tutorialsilly_rabbitzNo ratings yet

- OOSE Object Oriented Software Engineering ConceptsDocument25 pagesOOSE Object Oriented Software Engineering Conceptsapk95apkNo ratings yet

- ISCOM2824G Conifuguration20090519Document378 pagesISCOM2824G Conifuguration20090519Svetlin IvanovNo ratings yet

- Network On ChipDocument62 pagesNetwork On Chipsandyk_24No ratings yet

- Critical Reading-ArtsHumanities-hand Outs 5853487c802c3Document26 pagesCritical Reading-ArtsHumanities-hand Outs 5853487c802c3Rosatri HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Network Models & Facility Location ModelsDocument15 pagesIntroduction To Network Models & Facility Location Modelsmohcine zahidNo ratings yet

- Measures of Impact of Science and Technology on Indian AgricultureDocument318 pagesMeasures of Impact of Science and Technology on Indian AgricultureVikrant RaghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- Assignement 11.57 Residual PlotDocument11 pagesAssignement 11.57 Residual PlotMridul GuptaNo ratings yet

- GSM Library For Proteus PDFDocument14 pagesGSM Library For Proteus PDFAidi FinawanNo ratings yet

- Clark W Edwin Elementary Number TheoryDocument129 pagesClark W Edwin Elementary Number TheoryDireshan Pillay100% (1)

- Right brain left brain harmony Dieter RamsDocument31 pagesRight brain left brain harmony Dieter RamsAhmad Hafiz QifliNo ratings yet

- Autism and Its Homeopathic Cure - DR Bashir Mahmud ElliasDocument10 pagesAutism and Its Homeopathic Cure - DR Bashir Mahmud ElliasBashir Mahmud ElliasNo ratings yet

- Week2-The 8086 Microprocessor ArchitectureDocument48 pagesWeek2-The 8086 Microprocessor ArchitectureJerone CastilloNo ratings yet

- Project Management Best Practices Achieving GlobalDocument3 pagesProject Management Best Practices Achieving GlobalHua Hidari YangNo ratings yet

- C 1891601Document76 pagesC 1891601api-3729284No ratings yet

- Chapter 1to 4 NewDocument169 pagesChapter 1to 4 NewSunita ChaurasiaNo ratings yet

- Projectile Motion Worksheet Ans KeyDocument6 pagesProjectile Motion Worksheet Ans KeyFrengky WijayaNo ratings yet

- The Making of A Modern Filipino HouseDocument16 pagesThe Making of A Modern Filipino HouseIvy Joy CamposNo ratings yet

- CV - Reza Kurnia Ardani - Project EngineerDocument2 pagesCV - Reza Kurnia Ardani - Project Engineerreza39No ratings yet