Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jamadermatology Brindle 2019 Oi 190027

Uploaded by

Clinton SudjonoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jamadermatology Brindle 2019 Oi 190027

Uploaded by

Clinton SudjonoCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Dermatology | Original Investigation

Assessment of Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas

A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Richard Brindle, DM, FRCP; O. Martin Williams, PhD, FRCP, FRCPath; Edward Barton, BM, FRCPath;

Peter Featherstone, MPhil, FRCP

Supplemental content

IMPORTANCE The optimum antibiotic treatment for cellulitis and erysipelas lacks consensus. CME Quiz at

The available trial data do not demonstrate the superiority of any agent, and data are limited jamanetwork.com/learning

on the most appropriate route of administration or duration of therapy. and CME Questions page 1095

OBJECTIVE To assess the efficacy and safety of antibiotic therapy for non–surgically

acquired cellulitis.

DATA SOURCES The following databases were searched to June 28, 2016: Cochrane Central

Register of Controlled Trials (2016, issue 5), Medline (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), and

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Information System (LILACS) (from 1982). In

addition, 5 trials databases and the reference lists of included studies were searched.

Further searches of PubMed and Google Scholar were undertaken from June 28, 2016, to

December 31, 2018.

STUDY SELECTION Randomized clinical trials comparing different antibiotics, routes of

administration, and treatment durations were included.

DATA EXTRACTION AND SYNTHESIS For data collection and analysis, the standard

methodological procedures of the Cochrane Collaboration were used. For dichotomous

outcomes, the risk ratio and its 95% CI were calculated. A summary of findings table was

created for the primary end points, adopting the GRADE approach to assess the quality of

the evidence.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary outcome was the proportion of patients cured,

improved, recovered, or symptom-free or symptom-reduced at the end of treatment, as

reported by the trial. The secondary outcome was any adverse event.

RESULTS A total of 43 studies with a total of 5999 evaluable participants, whose age ranged

from 1 month to 96 years, were included. Cellulitis was the primary diagnosis in only 15

studies (35%), and in other studies the median (interquartile range) proportion of patients

with cellulitis was 29.7% (22.9%-50.3%). Overall, no evidence was found to support the

superiority of any 1 antibiotic over another, and antibiotics with activity against

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus did not add an advantage. Use of intravenous

antibiotics over oral antibiotics and treatment duration of longer than 5 days were not

supported by evidence.

Author Affiliations: Author

affiliations are listed at the end of this

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE In this systematic review and meta-analysis, only low-quality article.

evidence was found for the most appropriate agent, route of administration, and duration of Corresponding Authors: Owen

treatment for patients with cellulitis; future trials need to use a standardized set of outcomes, Martin Williams, PhD, FRCP, FRCPath,

Public Health England Microbiology

including severity scoring, dosing, and duration of therapy.

Services Bristol, and University

Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation

Trust, Bristol Royal Infirmary,

Marlborough Street, Bristol,

United Kingdom, BS2 8HW

(martinx.williams@uhbristol.nhs.uk);

Richard Brindle, DM, FRCP,

Department of Clinical Sciences,

University of Bristol, Bristol,

JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(9):1033-1040. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0884 United Kingdom (richard.brindle@

Published online June 12, 2019. bristol.ac.uk).

(Reprinted) 1033

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

Research Original Investigation Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas

C

ellulitis is a common acute skin infection.1 Published

guidelines for the management of cellulitis2-6 are mostly Key Points

based on evidence from studies of skin and soft tissue

Question What is the most appropriate antibiotic choice, route

infections, which have included cellulitis, or on expert opin- of administration, and duration of treatment for cellulitis?

ion. Despite the published guidance, substantial variations in

Findings In this systematic review of 43 studies that included

the antibiotic management of cellulitis have been identified.7,8

5999 participants, no evidence was found to support the

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to in-

superiority of any 1 antibiotic over another and the use of

form the production of evidence-based guidelines that cover intravenous over oral antibiotics; short treatment courses (5 days)

antibiotic choice, route of administration, duration of treat- appear to be as effective as longer treatment courses.

ment, the role of combinations of antibiotics, and gaps

Meaning In light of low-quality evidence found for the most

in research.

appropriate agent, route of administration, and duration of

treatment for patients with cellulitis, additional research is

required to define the optimum management of cellulitis.

Methods

group, number of participants who were cured or did not re-

We searched the following databases until June 28, 2016: spond to treatment, number of participants lost to follow-up,

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (2016, issue 5), and duration of follow-up. For all potential studies, 2 of us (R.B.

Medline (from 1946), Embase (from 1974), and LILACS and O.M.W.) independently extracted and analyzed the data,

(Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Information and 1 (R.B.) entered the data into RevMan, version 5.3 (Nordic

System; from 1982). We also searched 5 trial databases and the Cochrane Centre).10

reference lists of included studies. Further searches of PubMed Six types of bias were assessed11: selection, performance,

and Google Scholar were undertaken from June 28, 2016, to detection, attrition, reporting, and other bias (eAppendix 2 in

December 31, 2018. the Supplement). We followed the recommendations of the

We included studies of adults or children with a cellulitis Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions12

diagnosis that randomized participants to groups. We used the and categorized each included study as having high, low, or

term cellulitis to include erysipelas, as the 2 conditions can- unclear risk of bias.

not be readily distinguished. The focus of this review was cel-

lulitis requiring acute therapy with antibiotics rather than Statistical Analysis

prophylaxis. We considered a randomized clinical trial if a com- For studies in which similar types of interventions were com-

parison was made between different treatment regimens, pared, we performed a meta-analysis to calculate a weighted

including different antibiotics, routes of administration, and treatment effect across trials. A Mantel-Haenszel fixed-

duration of therapy. effects model was used to calculate a treatment effect when

The primary outcome of the proportion cured, improved, heterogeneity was low and the advantages of small studies

recovered, or symptom-free or symptom-reduced at the end would be overestimated by the random-effects analysis.

of treatment was commonly reported by patients or medical Because the number of included studies was low, we inter-

practitioners. No standard outcome measure was used be- preted I2 values of 50% or greater as representing substantial

cause each trial applied different time points and criteria to heterogeneity and applied a random-effects model. The

assess patient recovery or improvement. The secondary out- results are expressed as risk ratios (RRs) with 95% CIs for di-

come was any reported adverse events. chotomous outcomes.

We identified relevant randomized clinical trials pub- We assessed the reporting of withdrawals, dropouts, and

lished in the English language. The databases we searched and protocol deviations as well as whether participants were ana-

the search strategies we used are detailed in eAppendix 1 in the lyzed in the group to which they were originally randomized

Supplement. We checked bibliographies of included studies for (intention-to-treat population).

additional relevant trials. We did not perform a separate search

for adverse effects of the target interventions, but we did ex-

amine data on adverse effects in the included studies.

All studies of antibiotic therapy included in the previous

Results

2010 systematic review9 were included in this review. Poten- The study selection process is summarized in Figure 1. A sum-

tial studies for inclusion were independently reviewed by 2 of mary of findings, using the GRADE approach13 to assess the qual-

us (R.B. and O.M.W.) against the inclusion criteria. If both of ity of evidence, is included in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

us agreed that the study was not relevant to the objectives of Of the 41 studies included, 2 consisted of 2 sets of com-

this review, the study was excluded. If relevance was unclear parisons and were then treated as separate studies (Bucko et al

from the abstract, the 2 of us reviewed the full text. Any dis- 200214 and Daniel 199115), increasing the number of studies

agreement between us was resolved by consensus and re- to 43. One study was treated as 2 and thus is presented as 2

ferred to a third author (P. F.) if necessary. papers (Corey et al 201016 and Wilcox et al 201017).

Among the information we recorded from each study was The 43 studies included 5999 evaluable participants,

the population description, interventions, treatment dura- whose age ranged from 1 month to 96 years. Details of the stud-

tion, number of participants randomized into each treatment ies are summarized in eTable 2 in the Supplement. Cellulitis

1034 JAMA Dermatology September 2019 Volume 155, Number 9 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas Original Investigation Research

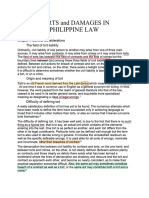

Figure 1. Flowchart of Article Selection

21 Full-text articles included 908 Records identified through 18 Records identified through

in 2010 review database search other sources

926 Records screened

779 Records discarded

147 Full-text articles assessed

for eligibility

25 Full-text articles discarded

103 Full-text articles excluded

19 Studies included in qualitative

synthesis

1 Study added

Of the original 21 articles, 2 were

43 Studies included in meta-analysis

treated as 2 separate studies and thus

are presented as 2 for the total of 43.

was the primary diagnosis in only 15 studies (35%), and in other Older vs Newer Cephalosporins

studies the proportion of patients with cellulitis ranged from We identified 6 studies14,18,19,26,27 (n = 527) that were orga-

8.9%18 to 90.9%,19 with a median (interquartile range) of 29.7% nized into 4 subgroups. No single cephalosporin was

(22.9%-50.3%). accepted as a standard for comparison. We defined the

Most studies compared different antibiotics or treatment du- newer cephalosporin as cephalosporin A and the older as

rations. No studies compared antibiotics with placebos. For most cephalosporin B. We found no difference between the 2

studies, the duration was allowed to vary, depending on clini- treatments (RR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.96-1.09) (eFigure 2.1 in the

cal need. Some trials had different durations but not with the Supplement). Only 1 study 26 reported data for adverse

same antibiotic. Because of the wide range of antibiotics used, events for the cellulitis subgroup; the cefazolin-probenecid

we could not analyze variations in antibiotic doses and outcomes. group experienced more adverse events compared with the

Because every study reported outcomes in different ways, IV ceftriaxone group (21% vs 10%), but this was not statisti-

we accepted the proportion cured as equivalent to the propor- cally different (RR = 0.50; 95% CI, 0.22-1.16; n = 134) (eFig-

tion with improved or reduced symptoms. The criteria for de- ure 2.2 in the Supplement).

termining improvement and the time points for assessment of

cure or improvement varied widely. The quality of follow-up β-lactam vs Macrolide, Lincosamide, or Streptogramin

ranged from the assessment of all participants to the assump- Two studies28,29 compared IV benzylpenicillin with an oral

tion that cure had occurred unless the participant returned. macrolide (roxithromycin) and a streptogramin (pristinamy-

The reason for the exclusion of most trials was they did not cin). Participants in both studies had uncomplicated erysip-

present results for the population with cellulitis, they were elas, presumed streptococcal, and were therefore penicillin

quasi–randomized clinical trials,20 or they had no obvious ran- sensitive. Another study compared oral cloxacillin with

domization process.21,22 The type of risk of bias for each study azithromycin,15 and a community study30 compared oral

is shown in Figure 2 and eAppendix 2 in the Supplement. flucloxacillin with oral erythromycin. A small study, which

included participants with cellulitis, compared cefalexin

Effects of Interventions with azithromycin.31

Penicillin vs Cephalosporins A further study compared oral clindamycin with

Three studies23-25 (n = 86) compared a penicillin with a cepha- sequential IV and oral flucloxacillin.32 In total, 6 studies

losporin. In 2 studies,23,24 intravenous (IV) ampicillin and sul- (n = 596) were found. We found no difference between the 2

bactam was compared with IV cefazolin, and a third study25 com- treatments (RR = 0.94; 95% CI, 0.85-1.04; I2 = 44%) (eFig-

pared IV ceftriaxone with IV flucloxacillin. We found no differ- ure 3.1 in the Supplement). This has been independently

ence between the 2 treatments. This outcome had high levels of published,33 including more studies but with similar find-

heterogeneity (RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.68-1.42; I2 = 70%) (eFigure 1.1 ings. Three studies reported adverse events.28,29,32 No sig-

in the Supplement). Two studies reported on adverse events.23,25 nificant differences were observed between the groups

No difference was found between the groups (RR = 0.48; 95% (RR = 0.70; 95% CI, 0.45-1.08; n = 397) (eFigure 3.2 in the

CI, 0.14-1.69; n = 68) (eFigure 1.2 in the Supplement). Supplement).

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology September 2019 Volume 155, Number 9 1035

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

Research Original Investigation Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas

Quinolone or Vancomycin vs Other Antibiotic

Figure 2. Type of Risk of Bias for Each Study

We found 3 studies (n = 160) comparing a quinolone with other

antibiotics: 1 compared a novel fluoroquinolone with

Random Sequence Generation

linezolid,34 1 compared moxifloxacin with a penicillin/beta-

Incomplete Outcome Data

Allocation Concealment

lactamase inhibitor combination,35 and 1 compared delafloxa-

Selective Reporting

cin with tigecycline.36 We found no difference between the

treatments (RR = 1.04; 95% CI, 0.94-1.16) (eFigure 4.1 in the

Other Bias

Supplement). Data on adverse events could not be extracted.

Blinding

We identified 10 studies (n = 2275), organized into 3 sub-

Study

Aboltins et al,58 2015 + + – + + +

groups comparing vancomycin with other antibiotics. We

Baig et al,30 1988 ? ? – + + ? found no difference between the 2 treatments (RR = 1.00; 95%

Bernard et al,29 1992 ? ? – + + ? CI, 0.98-1.02) (eFigure 5.1 in the Supplement).

Bernard et al,28 2002 + ? – + + ?

Boucher et al,37 2014 + + + + + ? Vancomycin Plus Gram-Positive, Plus Gram-Negative, or Alone

Brindle et al,53 2017 + + + + + + vs Other Antibiotic

Bucko et al,14 (1+2) 2002 + + + + + ?

One study37 (n = 625) compared vancomycin followed by oral li-

Chan,23 1995 ? ? + + + ?

nezolid with dalbavancin. No difference was observed between

Corey et al,16 2010 + + + + + ?

vancomycin alone or in combination and other antibiotics

Corey et al,38 2015 + + ? + + ?

Covington et al,34 2011 + + + + + ?

(RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-1.04) (eFigure 5.1.1 in the Supplement).

Daniel,15 (1) 1991 ? ? – – + ? Four studies (n = 853) compared vancomycin combined

Daniel,15 (2) 1991 ? ? – – ? ? with a gram-negative antibiotic: vancomycin with oritavan-

DiMattia et al,50 1981 + ? – – + ? cin (aztreonam allowed in both arms),38 vancomycin plus aztre-

Fabian et al,51 2005 + + + + + ? onam with ceftaroline fosamil,16,17 and vancomycin plus cefta-

Giordano et al,35 2005 ? ? + – + ? zidime with ceftobiprole medocaril.39 No difference was found

Grayson et al,26 2002 + + + + + +

between vancomycin alone or in combination and other

Hepburn et al,57 2004 + + ? – + ?

antibiotics (RR = 1.00; 95% CI, 0.96-1.05) (eFigure 5.1.2 in the

Iannini et al,27 1985 ? ? – – + ?

Supplement).

Kauf et al,40 2015 + ? – + + ?

Kiani,31 1991 ? ? + – + ?

We found 5 trials (n = 797) that compared vancomycin

Leman et al,52 2005 + + ? ? ? ? alone with other antibiotics: daptomycin,40,41 ceftobiprole,42

Miller et al,47 2015 + + + + + + a new pleuromutilin,43 and linezolid.44 We found no evi-

Moran et al,45 2014 + + + + ? ? dence of a difference between the 2 treatments (RR = 1.00; 95%

Moran et al,49 2017 + ? + + ? + CI, 0.97-1.03) (eFigure 5.1.3 in the Supplement).

Noel et al,42 2008 + + + ? ? ? The only study (n = 101) with cellulitis-specific adverse

Noel et al,39 2008 + ? + ? ? ?

events41 did not demonstrate a difference between the 2 treat-

O'Riordan et al,36 2015 + + + + + ?

ments (RR = 1.02; 95% CI, 0.42-2.51) (eFigure 5.2 in the Supple-

Pallin et al,48 2013 + + + ? + +

ment).

Pertel et al,41 2009 + ? – + + ?

Prince et al,43 2013 ? ? ? ? ? ?

Prokocimer et al,46 2013 + + + + + ? Linezolid vs Other Antibiotic

Rao et al,54 1985 + + – ? ? ? Four studies (n = 1024) compared linezolid with a variety of

Sachs and Pilgrim,24 1990 + ? – – ? ? other antibiotics: a novel fluoroquinolone, 34 tedizolid

Schwartz et al,19 1996 ? ? – – ? ? phosphate,45,46 and vancomycin.44 No difference was ob-

Tack et al,18 1998 ? ? + – ? ? served between linezolid and other antibiotics (RR = 1.00; 95%

Tarshis et al,55 2001 + + + – ? ?

CI, 0.95-1.05) (eFigure 6.1 in the Supplement). Data on

Thomas,32 2014 + + + ? ? +

adverse events could not be extracted.

Vinen et al,25 1996 ? ? – – ? ?

Weigelt et al,44 2005 ? ? – + ? ?

Wilcox et al,17 2010 + ? ? ? + ? Clindamycin vs Trimethoprim Sulfamethoxazole

Zeglaoui et al,56 2004 + + +– + ? ? One study47 (n = 248) compared clindamycin with trimethoprim-

sulfamethoxazole. This study was of uncomplicated skin infec-

Random sequence generation and allocation concealment are selection biases. tions and included participants with cellulitis in an area of high

Blinding is categorized as a performance bias and a detection bias. Incomplete community prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus

outcome data are an attrition bias, and selective reporting is a reporting bias. aureus (MRSA). No difference was found between clindamycin

Black positive indicates low risk of bias; blue question mark, unclear risk of bias;

and orange negative, high risk of bias. Bucko et al14 (1 + 2) is a single study and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (RR = 1.05; 95% CI, 0.96-

regarded in the analysis as 2 studies because the risk of bias for both arms is the 1.15) (eFigure 7.1 in the Supplement). Data on adverse events

same. Daniel15 (1) and (2) is also 1 study regarded as 2 separate studies because could not be extracted.

the risk of bias for the separate arms is different.

MRSA-Active vs Non–MRSA-Active Antibiotics

Two studies48,49 (n = 557) examined whether the addition of

antibiotics active against MRSA affected outcome. The MRSA-

1036 JAMA Dermatology September 2019 Volume 155, Number 9 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas Original Investigation Research

active arm (cephalosporin plus trimethoprim-sulfamethoxa- duration for the same antibiotic. One study38 compared a single

zole) was compared with cephalosporin plus placebo. There dose of oritavancin, a glycopeptide with a long half-life, with 7

was no difference between MRSA-active and non–MRSA- to 10 days of vancomycin. The 2 studies by Daniel15 compared

active antibiotics (RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.92-1.06) (eFigure 8.1 5 days of azithromycin with 7 days of either cloxacillin or eryth-

in the Supplement). One study49 actively excluded patients romycin. One study57 compared 5 days of oral levofloxacin with

with purulent cellulitis, whereas another48 included those with a 10-day regimen. Another study45 compared 6 days of tedi-

pustules less than 3 mm in maximal diameter. Although their zolid with 10 days of linezolid. No difference was found be-

numbers were small (n = 19), purulent cellulitis was not a fac- tween short and long antibiotic courses (RR = 0.99; 95% CI, 0.94-

tor in response to therapy.48 Both studies included data on ad- 1.04) (eFigure 10.1 in the Supplement). Only 1 study57 (n = 87)

verse events. We found no difference between the 2 treat- reported adverse events that led to participant withdrawal,

ments (RR = 1.03; 95% CI, 0.92-1.14; n = 642) (eFigure 8.2 in which was not statistically significant (RR = 0.33; 95% CI, 0.01-

the Supplement). 7.79) (eFigure 10.2 in the Supplement).

Other Studies Not Already Included Intravenous vs Oral Antibiotics

One study50 (n = 19) compared cefalexin 500 mg twice a day We identified 4 studies (n = 550), although the only study58

with 250 mg 4 times a day. No difference was observed be- designed specifically to compare oral with IV antibiotics was

tween the groups (RR = 1.00; 95% CI, 0.81-1.23) (eFigure 9.1 small (n = 47) and showed no statistical difference in out-

in the Supplement). comes. Two studies (n = 357) investigated an oral macrolide28

One study 51 compared meropenem with imipenem- or an oral streptogramin29 against IV benzylpenicillin. The oral

cilastatin for skin and skin-structure infection. No statisti- agents were shown to be more effective than the IV benzyl-

cally significant differences were found within the cellulitis penicillin. Pallin et al48 included data on route of administra-

subgroup (RR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.68-1.15; n = 81) (eFigure 9.2 in tion, although the study was not designed to examine

the Supplement). this route.

One study52 (n = 81) examined the addition of benzylpeni- For this outcome, we found low-quality evidence that IV

cillin to the regimen of those who receive flucloxacillin (tem- administration was inferior compared with oral administra-

perature, pain, or diameter of infected area were assessed on tion (RR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.75-0.93; P < .001) (eFigure 11.1 in the

days 1 and 2 of treatment). No statistically significant effect on Supplement). Although more adverse events occurred in the

symptoms (RR = 0.98; 95% CI, 0.87-1.09) (eFigure 9.3 in the oral administration group, no statistically significant differ-

Supplement) was found. No adverse effects were reported in ence was observed between the groups (RR = 1.11; 95% CI, 0.73-

either arm of the study. 1.68; n = 549; I2 = 46%) (eFigure 11.2 in the Supplement).

One study53 (n = 410) compared flucloxacillin plus clinda-

mycin with flucloxacillin plus placebo and found no statisti-

cally significant difference between the 2 allocations at day 5

follow-up (RR = 1.07; 95% CI, 0.98-1.18) (eFigure 9.4.1 in the

Discussion

Supplement). A statistically significant difference in adverse From the data presented, defining the most effective antibi-

events was observed, specifically diarrhea, occurring twice as otic treatment for cellulitis was not possible, given that no

frequently in the clindamycin group (RR = 1.87; 95% CI, 1.23- 1 antibiotic was superior over another. The use of a cephalo-

2.86; P = .004) (eFigure 9.4.2 in the Supplement). sporin rather than a penicillin was not supported despite trials

One study54 (n = 18) compared ticarcillin and clavulanic that showed equivalence.23-25,54 Similarly, glycopeptide,37,38

acid with moxalactam. No difference between the groups was oxazolidinone,44 and daptomycin41 did not show superiority

found (RR = 1.00; 95% CI, 0.82-1.22) (eFigure 9.5 in the Supple- to the other antibiotics. The use of combination therapy was

ment). not supported, as the trials with combination therapy did not

One study55 compared oral gatifloxacin with oral levo- demonstrate better outcomes.48,49,52,53

floxacin as part of a skin and skin-structure infection trial. The use of oral therapy was supported by the limited data

A small but statistically significant difference was found, fa- for oral vs IV antibiotics and by trials in which only oral anti-

voring gatifloxacin (RR = 1.17; 95% CI, 1.01-1.35; n = 82; P = .03; biotics were used with good outcome. The earliest studies of

low-quality evidence) (eFigure 9.6 in the Supplement). antimicrobials for erysipelas administered the drugs orally with

One study56 (n = 112) compared IV benzylpenicillin with good outcomes.21,22 In this review, when oral antibiotics were

intramuscular penicillin (benzylpenicillin and procaine peni- compared with IV treatments, the oral treatments appeared

cillin) for 10 days. No difference in outcome was observed more effective.28,29,48,58

(RR = 0.93; 95% CI, 0.79-1.10) (eFigure 9.7.1 in the Supple- Identifying the optimum duration of antibiotic therapy was

ment), but more adverse events occurred in the IV group not possible, with only 1 trial designed to look specifically at

(RR = 7.25; 95% CI, 1.73-30.45; P = .007) (eFigure 9.7.2 in the duration,57 but no supporting evidence was found for antibi-

Supplement). otic therapy longer than 5 days.15 The trial by Hepburn et al57

only randomized to longer treatment at day 5, which did not

Shorter vs Longer Courses of Antibiotics clarify whether prolonged antibiotic treatment for those pa-

We identified 5 studies (n = 916) that compared a shorter with tients who were slow to improve made any difference to the

a longer duration of treatment. Only 1 study57 compared the rate of improvement or final outcome. An antibiotic with

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology September 2019 Volume 155, Number 9 1037

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

Research Original Investigation Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas

activity against MRSA in cellulitis was investigated in more recent studies provided sample size calculations. Eleven

2 trials.48,49 Neither trial showed the advantage of this antibi- studies15,19,24,29-31,40,44,54,58 were described as open, with 5 ad-

otic, however, supporting the view that cellulitis is primarily ditional studies presumed to be not blinded (their design was

a streptococcal infection. not specified).25,27,28,50,56 This lack of blinding, in combina-

tion with a lack of objective outcome measures, could

Limitations increase the risk of bias.11

This study has several limitations. Most of the included stud-

ies lacked consistent, clear, and precise end points for cellu- Implications for Research

litis therapies, making comparison between treatments In light of the low quality of evidence we identified, addi-

difficult.59 Standard end points are needed with which assess- tional research is required to define the optimum manage-

ment is made and to which subsequent trials should all ad- ment of cellulitis. Future clinical trials should only include par-

here. These end points must be objective (eg, no further swell- ticipants with cellulitis and address specific issues associated

ing, neutrophil level within the normal range) and not with therapy. Trials need to clarify the duration of therapy and

subjective (eg, discharge from hospital, IV to oral switch). Ac- whether longer durations are necessary with more severe dis-

cording to interviews with participants, the outcomes of in- ease. None of the trials included dose comparisons, and the

terest to them were time to resolution of unpleasant symp- tendency may be to increase the dose to resolve treatment fail-

toms, such as pain,60 yet only 6 studies41,45,48,52,53,58 gave ures without testing this hypothesis. Future trials need to

information on symptom reduction. A more common out- clarify dosing and whether dosing should be based on actual

come was the proportion of patients cured or improved, an as- or ideal body weight.

sessment often timed at the end of treatment or up to 2 weeks Randomized clinical trials should be conducted compar-

after treatment and defined as the reduction or absence of the ing IV with oral antibiotics for participants within a commu-

original signs or symptoms. This timing or definition does not nity setting; the results of such trials would have implica-

allow discrimination between treatments, which may affect the tions for the delivery and cost-effectiveness of home therapy,

duration of symptoms or the length of hospital stay. minimizing the involvement of home IV services or frequent

Older studies either did not specify or did not exclude par- outpatient hospital visits. In addition, trials need to have stan-

ticipants who had received previous antibiotic therapy and in- dardized criteria for severity scoring (eg, Systemic Inflamma-

cluded people who did not respond to community treatment. tory Response Syndrome criteria, renal function, and area of

In contrast, 17 studies excluded participants who had re- erythema) to allow the examination of treatment route, dos-

ceived antibiotics before enrollment, although the exclusion ing, and duration. A standardized set of outcomes needs to be

period varied between studies. established for these trials. These outcomes should include sys-

Many trials included mixed populations with a range of skin temic features (eg, heart rate, blood pressure) as well as local

and skin-structure infections; unless they presented sub- (eg, inflammation, swelling), blood (eg, neutrophils, urea), and

group data for those with cellulitis, we were unable to in- patient-focused (eg, nausea, pain, mobility) measures. Trial ex-

clude these studies. The decision to show these data may be clusions (eg, duration of antibiotics prior to trial entry) and

biased, because researchers may prefer to show data for spe- times of follow-up (eg, early, late, and back-to-normal activi-

cific disease groups if the response to the treatments varied. ties) should be standardized whenever possible.

In most trials, the causative organisms were not isolated.

Many studies with mixed-disease populations reported sub-

group data for causal organisms but not the type of tissue in-

volvement. Isolation rates for causal organisms were gener-

Conclusions

ally low for cellulitis,27,51 rarely higher than 25%. This rate Current evidence does not support the superiority of any

means that, in some studies, 75% of participants with celluli- 1 antibiotic over another, and the use of a combination of

tis would be excluded. antibiotics is not supported by clinical trial data. There is a lack

A number of studies did not adequately explain the pro- of evidence favoring the use of intravenous over oral antibi-

cess of allocation concealment or blinding (Figure 2), and only otics or for treatment durations longer than 5 days.

ARTICLE INFORMATION Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth Hospitals, Administrative, technical, or material support:

Accepted for Publication: March 22, 2019. Portsmouth, United Kingdom (Featherstone). Brindle, Williams, Featherstone.

Author Contributions: Drs Brindle and Williams Supervision: Brindle, Williams.

Published Online: June 12, 2019.

doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0884 had full access to all the data in the study and take Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

responsibility for the integrity of the data and the Meeting Presentation: The results of this study

Author Affiliations: Department of Clinical accuracy of the data analysis.

Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, United were presented at the ASM Microbe 2018, June 8,

Concept and design: Brindle, Williams, 2018, Atlanta, Georgia.

Kingdom (Brindle); Public Health England Featherstone.

Microbiology Services Bristol, Bristol, United Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Additional Contributions: The authors wish to

Kingdom (Williams); University Hospitals Bristol Brindle, Williams, Barton. thank the Cochrane Skin Group for assistance with

NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol Royal Infirmary, Drafting of the manuscript: All authors. the initial searches. No compensation outside of

Bristol, United Kingdom (Williams); North Cumbria Critical revision of the manuscript for important usual salary was received.

University Hospitals NHS Trust, Carlisle, United intellectual content: All authors.

Kingdom (Barton); Acute Medicine Unit, Queen Statistical analysis: Brindle.

1038 JAMA Dermatology September 2019 Volume 155, Number 9 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas Original Investigation Research

REFERENCES skin-structure infections. Clin Ther. 2002;24(7): erysipelas in adults: a comparative study. Br J

1. Hay RJ, Morris-Jones R. Rook’s Textbook of 1134-1147. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(02)80024-8 Dermatol. 1992;127(2):155-159. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.

Dermatology. Vol 3. 9th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 15. Daniel R; European Azithromycin Study Group. 1992.tb08048.x

2016. Azithromycin, erythromycin and cloxacillin in the 29. Bernard P, Chosidow O, Vaillant L; French

2. British Lymphology Society; Lymphoedema treatment of infections of skin and associated soft Erysipelas Study Group. Oral pristinamycin versus

Support Network. Consensus document on the tissues. J Int Med Res. 1991;19(6):433-445. doi:10. standard penicillin regimen to treat erysipelas in

management of cellulitis in lymphoedema. 1177/030006059101900602 adults: randomised, non-inferiority, open trial. BMJ.

https://www.lymphoedema.org/images/pdf/ 16. Corey GR, Wilcox MH, Talbot GH, Thye D, 2002;325(7369):864-869. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.

CellulitisConsensus.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2019. Friedland D, Baculik T; CANVAS 1 investigators. 7369.864

3. Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team CANVAS 1: the first Phase III, randomized, 30. Baig A, Grillage MG, Welch RB. A comparison of

(CREST). Guideline on the Management of Cellulitis double-blind study evaluating ceftaroline fosamil erythromycin and flucloxacillin in the treatment of

in Adults. Belfast, UK: CREST; 2005. for the treatment of patients with complicated skin infected skin lesions in general practice. Br J Clin Pract.

http://www.acutemed.co.uk/docs/Cellulitis% and skin structure infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1988;42(3):110-115.

20guidelines,%20CREST,%2005.pdf. Accessed 2010;65(suppl 4):iv41-iv51. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq254 31. Kiani R. Double-blind, double-dummy

May 9, 2019. 17. Wilcox MH, Corey GR, Talbot GH, Thye D, comparison of azithromycin and cephalexin in the

4. Eron LJ, Lipsky BA, Low DE, Nathwani D, Tice Friedland D, Baculik T; CANVAS 2 investigators. treatment of skin and skin structure infections. Eur

AD, Volturo GA; Expert Panel on Managing Skin and CANVAS 2: the second Phase III, randomized, J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10(10):880-884.

Soft Tissue Infections. Managing skin and soft double-blind study evaluating ceftaroline fosamil doi:10.1007/BF01975848

tissue infections: expert panel recommendations for the treatment of patients with complicated skin 32. Thomas MG. Oral clindamycin compared with

on key decision points. J Antimicrob Chemother. and skin structure infections. J Antimicrob Chemother. sequential intravenous and oral flucloxacillin in the

2003;52(suppl 1):i3-i17. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg466 2010;65(suppl 4):iv53-iv65. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq255 treatment of cellulitis in adults: a randomized,

5. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al; 18. Tack KJ, Littlejohn TW, Mailloux G, Wolf MM, double-blind trial. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2014;22(6):

Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice Keyserling CH; Cefdinir Adult Skin Infection Study 330-334. doi:10.1097/IPC.0000000000000146

guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Group. Cefdinir versus cephalexin for the treatment 33. Ferreira A, Bolland MJ, Thomas MG.

skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the of skin and skin-structure infections. Clin Ther. Meta-analysis of randomised trials comparing a

Infectious Diseases Society of America [published 1998;20(2):244-256. doi:10.1016/S0149-2918(98) penicillin or cephalosporin with a macrolide or

correction appears in Clin Infect Dis. 80088-X lincosamide in the treatment of cellulitis or

2015;60(9):1448]. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(2): 19. Schwartz R, Das-Young LR, Ramirez-Ronda C, erysipelas. Infection. 2016;44(5):607-615. doi:10.

e10-e52. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu296 Frank E. Current and future management of serious 1007/s15010-016-0895-x

6. Societe Francaise de Dermatologie. Erysipèle et skin and skin-structure infections. Am J Med. 1996; 34. Covington P, Davenport JM, Andrae D, et al.

fasciite nécrosante: prise en charge [Management 100(6A):90S-95S. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(96) Randomized, double-blind, phase II, multicenter

of erysipelas and necrotizing fasciitis]. Ann 00111-8 study evaluating the safety/tolerability and efficacy

Dermatol Venereol. 2001;128(3 Pt 2):463-482. 20. Jorup-Rönström C, Britton S. Recurrent of JNJ-Q2, a novel fluoroquinolone, compared with

7. Dong SL, Kelly KD, Oland RC, Holroyd BR, Rowe erysipelas: predisposing factors and costs of linezolid for treatment of acute bacterial skin and

BH. ED management of cellulitis: a review of five prophylaxis. Infection. 1987;15(2):105-106. doi:10. skin structure infection. Antimicrob Agents

urban centers. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(7):535-540. 1007/BF01650206 Chemother. 2011;55(12):5790-5797. doi:10.1128/AAC.

doi:10.1053/ajem.2001.28330 21. Snodgrass WR, Anderson T. Prontosil in 05044-11

8. Williams OM, Brindle RJ; South West Regional erysipelas. Br Med J. 1937;2(3993):101-104. doi:10. 35. Giordano P, Song J, Pertel P, Herrington J,

Microbiology Group (SWRMG). Audit of guidelines 1136/bmj.2.3993.101 Kowalsky S. Sequential intravenous/oral

for antimicrobial management of cellulitis across 22. Snodgrass WR, Anderson T. Sulphanilamide in moxifloxacin versus intravenous piperacillin-

English NHS hospitals reveals wide variation. J Infect. the treatment of erysipelas. Br Med J. 1937;2(4014): tazobactam followed by oral amoxicillin-clavulanate

2016;73(3):291-293. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2016.06.002 1156-1159. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4014.1156 for the treatment of complicated skin and skin

structure infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2005;

9. Kilburn SA, Featherstone P, Higgins B, Brindle R. 23. Chan JC. Ampicillin/sulbactam versus cefazolin 26(5):357-365. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.07.017

Interventions for cellulitis and erysipelas. Cochrane or cefoxitin in the treatment of skin and

Database Syst Rev. 2010;(6):CD004299. skin-structure infections of bacterial etiology. Adv 36. O’Riordan W, Mehra P, Manos P, Kingsley J,

Ther. 1995;12(2):139-146. Lawrence L, Cammarata S. A randomized phase 2

10. Manager R. 5. RevMan, Version 5.3. Copenhagen, study comparing two doses of delafloxacin with

Denmark: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane 24. Sachs MK, Pilgrim C. Ampicillin/sulbactam tigecycline in adults with complicated skin and

Collaboration; 2014. compared with cefazolin or cefoxitin for the skin-structure infections. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;30:

11. Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews treatment of skin and skin structure infections. 67-73. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2014.10.009

in health care: assessing the quality of controlled Drug Investig. 1990;2(3):173-183. doi:10.1007/

BF03259192 37. Boucher HW, Wilcox M, Talbot GH, Puttagunta

clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323(7303):42-46. doi:10. S, Das AF, Dunne MW. Once-weekly dalbavancin

1136/bmj.323.7303.42 25. Vinen J, Hudson B, Chan B, Fernandes C. versus daily conventional therapy for skin infection.

12. Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook A randomised comparative study of once-daily N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2169-2179. doi:10.

for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Version ceftriaxone and 6-hourly flucloxacillin in the 1056/NEJMoa1310480

5.1.0; Updated March 2011. London, UK: The Cochrane treatment of moderate to severe cellulitis. Clin Drug

Investig. 1996;12(5):221-225. doi:10.2165/ 38. Corey GR, Good S, Jiang H, et al; SOLO II

Collaboration; 2011. Investigators. Single-dose oritavancin versus 7-10

00044011-199612050-00001

13. Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, days of vancomycin in the treatment of

eds. Introduction to GRADE Handbook: Handbook 26. Grayson ML, McDonald M, Gibson K, et al. gram-positive acute bacterial skin and skin

for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Once-daily intravenous cefazolin plus oral structure infections: the SOLO II noninferiority

Recommendation Using the GRADE Approach. The probenecid is equivalent to once-daily intravenous study. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(2):254-262. doi:10.

GRADE Working Group. http://gdt. ceftriaxone plus oral placebo for the treatment of 1093/cid/ciu778

guidelinedevelopment.org/app/handbook/ moderate-to-severe cellulitis in adults. Clin Infect Dis.

2002;34(11):1440-1448. doi:10.1086/340056 39. Noel GJ, Bush K, Bagchi P, Ianus J, Strauss RS.

handbook.html. Updated October 2013. Accessed A randomized, double-blind trial comparing

May 9, 2019. 27. Iannini PB, Kunkel MJ, Link ASJ, Simons WJ, Lee ceftobiprole medocaril with vancomycin plus

14. Bucko AD, Hunt BJ, Kidd SL, Hom R. TJ, Tight RR. Multicenter comparison of cefonicid ceftazidime for the treatment of patients with

Randomized, double-blind, multicenter comparison and cefazolin in hospitalized patients with skin and complicated skin and skin-structure infections. Clin

of oral cefditoren 200 or 400 mg BID with either soft tissue infections. Adv Ther. 1985;2(5):214-224. Infect Dis. 2008;46(5):647-655. doi:10.1086/526527

cefuroxime 250 mg BID or cefadroxil 500 mg BID 28. Bernard P, Plantin P, Roger H, et al.

for the treatment of uncomplicated skin and Roxithromycin versus penicillin in the treatment of

jamadermatology.com (Reprinted) JAMA Dermatology September 2019 Volume 155, Number 9 1039

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

Research Original Investigation Antibiotic Treatment of Cellulitis and Erysipelas

40. Kauf TL, McKinnon P, Corey GR, et al. An acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections: Open. 2017;7(3):e013260. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-

open-label, pragmatic, randomized controlled the ESTABLISH-1 randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;309 2016-013260

clinical trial to evaluate the comparative (6):559-569. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.241 54. Rao B, See RC, Chuah SK, Bansal MB, Lou MA,

effectiveness of daptomycin versus vancomycin for 47. Miller LG, Daum RS, Creech CB, et al; DMID Thadepalli H. Ticarcillin plus clavulanic acid versus

the treatment of complicated skin and skin 07-0051 Team. Clindamycin versus moxalactam in the treatment of skin and soft tissue

structure infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:503-512. trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for uncomplicated infections. Am J Med. 1985;79(5B):126-129. doi:10.

doi:10.1186/s12879-015-1261-9 skin infections. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1093-1103. 1016/0002-9343(85)90144-5

41. Pertel PE, Eisenstein BI, Link AS, et al. The doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1403789 55. Tarshis GA, Miskin BM, Jones TM, et al.

efficacy and safety of daptomycin vs. vancomycin 48. Pallin DJ, Binder WD, Allen MB, et al. Clinical Once-daily oral gatifloxacin versus oral levofloxacin

for the treatment of cellulitis and erysipelas. Int J trial: comparative effectiveness of cephalexin plus in treatment of uncomplicated skin and soft tissue

Clin Pract. 2009;63(3):368-375. doi:10.1111/j.1742- trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole versus cephalexin infections: double-blind, multicenter, randomized

1241.2008.01988.x alone for treatment of uncomplicated cellulitis: study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(8):

42. Noel GJ, Strauss RS, Amsler K, Heep M, Pypstra a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2013; 2358-2362. doi:10.1128/AAC.45.8.2358-2362.2001

R, Solomkin JS. Results of a double-blind, 56(12):1754-1762. doi:10.1093/cid/cit122 56. Zeglaoui F, Dziri C, Mokhtar I, et al.

randomized trial of ceftobiprole treatment of 49. Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Mower WR, et al. Intramuscular bipenicillin vs. intravenous penicillin

complicated skin and skin structure infections Effect of cephalexin plus trimethoprim- in the treatment of erysipelas in adults: randomized

caused by gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob sulfamethoxazole vs cephalexin alone on clinical controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.

Agents Chemother. 2008;52(1):37-44. doi:10.1128/ cure of uncomplicated cellulitis: a randomized 2004;18(4):426-428. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.

AAC.00551-07 clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(20):2088-2096. doi: 00938.x

43. Prince WT, Ivezic-Schoenfeld Z, Lell C, et al. 10.1001/jama.2017.5653 57. Hepburn MJ, Dooley DP, Skidmore PJ, Ellis MW,

Phase II clinical study of BC-3781, a pleuromutilin 50. DiMattia AF, Sexton MJ, Smialowicz CR, Knapp Starnes WF, Hasewinkle WC. Comparison of

antibiotic, in treatment of patients with acute WH Jr. Efficacy of two dosage schedules of short-course (5 days) and standard (10 days)

bacterial skin and skin structure infections. cephalexin in dermatologic infections. J Fam Pract. treatment for uncomplicated cellulitis. Arch Intern

Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(5):2087- 1981;12(4):649-652. Med. 2004;164(15):1669-1674. doi:10.1001/

2094. doi:10.1128/AAC.02106-12 archinte.164.15.1669

51. Fabian TC, File TM, Embil JM, et al. Meropenem

44. Weigelt J, Itani K, Stevens D, Lau W, Dryden M, versus imipenem-cilastatin for the treatment of 58. Aboltins CA, Hutchinson AF, Sinnappu RN,

Knirsch C; Linezolid CSSTI Study Group. Linezolid hospitalized patients with complicated skin and et al. Oral versus parenteral antimicrobials for the

versus vancomycin in treatment of complicated skin structure infections: results of a multicenter, treatment of cellulitis: a randomized non-inferiority

skin and soft tissue infections. Antimicrob Agents randomized, double-blind comparative study. Surg trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70(2):581-586.

Chemother. 2005;49(6):2260-2266. doi:10.1128/ Infect (Larchmt). 2005;6(3):269-282. doi:10.1089/ doi:10.1093/jac/dku397

AAC.49.6.2260-2266.2005 sur.2005.6.269 59. Smith E, Patel M, Thomas KS. Which outcomes

45. Moran GJ, Fang E, Corey GR, Das AF, De Anda 52. Leman P, Mukherjee D. Flucloxacillin alone or are reported in cellulitis trials? results of a review of

C, Prokocimer P. Tedizolid for 6 days versus combined with benzylpenicillin to treat lower limb outcomes included in cellulitis trials and a patient

linezolid for 10 days for acute bacterial skin and cellulitis: a randomised controlled trial. Emerg Med J. priority setting survey. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):

skin-structure infections (ESTABLISH-2): 2005;22(5):342-346. doi:10.1136/emj.2004.019869 1028-1034. doi:10.1111/bjd.16235

a randomised, double-blind, phase 3,

non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8): 53. Brindle R, Williams OM, Davies P, et al. 60. Carter K, Kilburn S, Featherstone P. Cellulitis

696-705. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70737-6 Adjunctive clindamycin for cellulitis: a clinical trial and treatment: a qualitative study of experiences.

comparing flucloxacillin with or without Br J Nurs. 2007;16(6):S22-S24, S26-S28. doi:10.

46. Prokocimer P, De Anda C, Fang E, Mehra P, Das clindamycin for the treatment of limb cellulitis. BMJ 12968/bjon.2007.16.Sup1.27089

A. Tedizolid phosphate vs linezolid for treatment of

1040 JAMA Dermatology September 2019 Volume 155, Number 9 (Reprinted) jamadermatology.com

© 2019 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ by Sheren Regina on 11/28/2019

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- A Cappella Arranging: Finding New Meaning in Familiar SongsDocument18 pagesA Cappella Arranging: Finding New Meaning in Familiar SongsJUAN SEBASTIAN GARCIA SANTANANo ratings yet

- Bharani Nakshatra Unique Characteristics and CompatibilityDocument5 pagesBharani Nakshatra Unique Characteristics and Compatibilityastroprophecy100% (2)

- Bob Cassidy - Séance Post Lecture NotesDocument9 pagesBob Cassidy - Séance Post Lecture NotesNedim GuzelNo ratings yet

- Pte Academic Practice Tests Plus2Document18 pagesPte Academic Practice Tests Plus2Majin BalaNo ratings yet

- What Is Round Robin SchedulingDocument5 pagesWhat Is Round Robin Schedulingtridibearth100% (3)

- Evaluate The Effectiveness of The Domestic and International Legal Systems in Dealing With International CrimeDocument3 pagesEvaluate The Effectiveness of The Domestic and International Legal Systems in Dealing With International CrimeDiana NguyenNo ratings yet

- T Ha, Aj Ivika or Aj Ivaka. Irtha Nkara of The Jainas The NameDocument19 pagesT Ha, Aj Ivika or Aj Ivaka. Irtha Nkara of The Jainas The Namemohammed9000No ratings yet

- Funds Study Guide AnswersDocument82 pagesFunds Study Guide AnswersSophia CuertoNo ratings yet

- Savitri Devi - Joy of The Sun (1942)Document113 pagesSavitri Devi - Joy of The Sun (1942)anon-644759100% (2)

- Strategic Intervention Material in MathDocument15 pagesStrategic Intervention Material in Mathshe79% (24)

- Direct Appeal To The Supreme CourtDocument6 pagesDirect Appeal To The Supreme CourtFrancesco Celestial BritanicoNo ratings yet

- Espano v. CA, 288 Scra 588Document9 pagesEspano v. CA, 288 Scra 588Christia Sandee SuanNo ratings yet

- Grade 5 DLL English 5 Q2 Week 6Document4 pagesGrade 5 DLL English 5 Q2 Week 6kotarobrother2350% (2)

- Wenjun Herminado QuizzzzzDocument3 pagesWenjun Herminado QuizzzzzWenjunNo ratings yet

- WK 8 Conflict - Management - Skills LaptopDocument24 pagesWK 8 Conflict - Management - Skills LaptopAMEERA SHAFIQA MOHD RASHIDNo ratings yet

- Abdul Wahid F 2017 PHD ThesisDocument190 pagesAbdul Wahid F 2017 PHD Thesisfrancisco javier OlguinNo ratings yet

- BHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413Document3 pagesBHLP Year Long Plan Required English Medium 2023 24 Batch Final 991676721629413A V GamingNo ratings yet

- Routing in Telephone NetworkDocument27 pagesRouting in Telephone NetworkAmanuel Tadele0% (2)

- Mandatory ROTCDocument7 pagesMandatory ROTCphoebe lagueNo ratings yet

- Greatest and Least Integer FunctionsDocument11 pagesGreatest and Least Integer FunctionsAbhishek SinghNo ratings yet

- 5 L1 Aspen TutorialDocument28 pages5 L1 Aspen TutorialariefNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Survey DesignDocument28 pagesChapter 12 Survey DesignTrisha GonzalesNo ratings yet

- An Efficient Supply Management in Water Flow NetwoDocument15 pagesAn Efficient Supply Management in Water Flow NetwoSARAL JNo ratings yet

- Jarencio Chapter 1 PDFDocument8 pagesJarencio Chapter 1 PDFHannah Keziah Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- Case Law AnalysisDocument8 pagesCase Law Analysisapi-309579746No ratings yet

- Combo CV Template10Document2 pagesCombo CV Template10Jay LacanlaleNo ratings yet

- Listening ExercisesDocument4 pagesListening ExerciseslupsumetroNo ratings yet

- Manipulative Information and Media: Reporters: Jo-An Pauline Casas Jhon Lee CasicasDocument33 pagesManipulative Information and Media: Reporters: Jo-An Pauline Casas Jhon Lee CasicasCasas, Jo-an Pauline A.100% (1)

- Expatriate Failure and The Role of Expatriate TrainingDocument11 pagesExpatriate Failure and The Role of Expatriate TrainingDinesh RvNo ratings yet

- 1basic Concepts of Growth and DevelopmentDocument100 pages1basic Concepts of Growth and Developmentshweta nageshNo ratings yet