Professional Documents

Culture Documents

21

Uploaded by

Erica LesmanaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

21

Uploaded by

Erica LesmanaCopyright:

Available Formats

POLICY BRIEF

Simplify, Simplify, Simplify: The First

Principle of Tax Reform

BY PAUL WEINSTEIN JR. JULY 2013

Overhauling the federal tax system is one of the most important steps U.S. politi-

cal leaders can take to promote economic growth and fairness. It is also that rar-

est of issues in today’s Washington—one that commands broad support on both

PPI believes we need a sides of the political aisle. For these reasons, the Progressive Policy Institute urges

the White House and Congress to give top priority to fixing our broken tax system

federal tax system that

over the next 12 months.

is simpler and more

progressive. Everyone knows our tax code is too complicated, too inefficient and too riddled

with preferences for special interests. Americans deserve better. PPI believes we

need a federal tax system that is simpler and more progressive; that steers in-

vestment into productive, job-creating activity; that enables U.S. workers and

companies to compete on an even footing in world markets; and, that serves the

most basic purpose of any tax system—raising enough revenue to finance the gov-

ernment while ensuring fairness to taxpayers.

Comprehensive tax reform obviously poses daunting political obstacles. Neverthe-

less, it’s a goal Democrats and Republicans share. The Senate Finance Committee

has published 10 papers on various options while the House Ways and Means

Committee has organized 11 subgroups to consider different areas of the tax law.

Over 1000 comments have been filed. With Sen. Max Baucus retiring this year,

and Rep. Dave Camp term-limited as chair of the House Ways and Means Com-

mittee, the two most important players on tax policy are strongly motivated to get

something done.

This paper will not offer a sweeping blueprint for reform. Instead it focuses on

one crucial aspect of reform: Simplification. PPI has long argued that our tax sys-

tem is too complex and ill-fitted to the needs of middle-class families and small

entrepreneurs. They benefit little from the existing array of incentives and loop-

holes, which are mainly targeted on special interests or people with a level of in-

come and wealth they can only dream about. The code’s byzantine complexity also

costs business and individuals hundreds of billions in compliance. In a recently

released annual report to Congress, the IRS's National Taxpayer Advocate, Nina

Olson, estimated that individual and business taxpayers spent 6.1 billion hours to

PRO GRE SSIV E P OLICY INS TITU TE | PO LICY BR IEF 1

complete filings. The bloated federal code contains almost four million words and

on average has more than one new provision added to it daily.1

The code is so complex that nearly 60 percent of taxpayers hire paid preparers

and another 30 percent rely on commercial software to prepare their returns.2

In fact, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers, only four nations have more pages

of “primary tax legislation” than does the United States. And the World Bank’s

www.doingbusiness.org ranks 61 nations as having tax systems friendlier to busi-

ness than does the United States, while the World Economic Forum puts the U.S.

tax system in 107th place in a ranking of the efficiency of 117 national tax regimes.

Congress perennially fiddles with the code, and it takes a full-time army of lobby-

ists to keep track of all the changes: the Treasury Department reports that there

have been more than 14,400 revisions since 1986. It is imperative, then, that any

comprehensive overhaul of the federal tax system not make the code even bigger

and more complicated. Tax reform without dramatic simplification should not be

considered genuine reform.

What is Simplification?

We often hear talk about simplification from both sides of the political aisle. But

there is a lot of confusion about what constitutes tax simplification and how to

ensure the vast majority of Americans will benefit. In fact some reform plans that

claim they would simplify the tax code and the process of filing taxes would actu-

ally make the current system worse in several important ways.

Simplification should never leave most Americans, particularly low- and middle-

income families, worse off than the current system nor should it abandon the

principle of progressive taxation. One example of such an approach is the so-

called ‘flat tax’ that would collapse the current 5 marginal rates into one. The flat

tax sounds simple, but in order to ensure the government doesn’t worsen our al-

ready historically high federal deficit, the rate would be considerably higher than

the 15 percent rate most taxpayers pay today. That means the vast majority of

Americans would be saddled with a substantial tax hike all in the name of creating

a tax code with a single rate.

Just as problematic are political gimmicks that would pretend to simplify while in

actuality maintain the current system of excess complexity. For example, ‘return

free filing’ has been proposed as a solution to taxpayer woes. Under this proposal,

the Internal Revenue Service would just calculate your taxes for you—no fuss, no

muss.

However beguiling that might sound to some, there are several big problems with

this idea. First, you can’t change an old jalopy into a sports car simply by painting

it red—under the hood the tax system would be just as complex, hard to under-

stand, and dysfunctional. Indeed, return-free can actually hide tax dysfunctionali-

PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE | POLICY BRIEF 2

ty and inefficiency by making it invisible to citizens, which would work at cross-

purposes to the long-term improvements and reform of the tax system that are

long overdue.

Second, there’s the inherent conflict of interest in having the taxman do your tax-

es. If there’s any question about how to apply the tax code, the IRS is likely to

choose the interpretation that brings in more taxes. Finally, to the degree that the

IRS actually tries to figure out the right level of taxes due—rather than simply

charging the highest number—return free filing is likely to be expensive to im-

plement. Indeed, there’s already free solutions for tax return preparation—IRS

Free File—that relies on the private sector without costing taxpayers a dime. And,

this idea has been tried in the United States. Under California’s Ready Return, of

the millions of taxpayers offered the government-prepared returns, less than a

hundred thousand taxpayers a year have taken up the State's offer which would be

sent to them just like their real estate or property tax bills. At the end of the day,

Ready Return was an experiment that failed to persuade taxpayers that govern-

ment revenue agencies should be their tax preparer.

But there is a more positive reason why it is in the nation’s interest to keep the

citizen directly engaged in their own tax compliance obligations. The annual tax

ritual is for some individuals and families the one time when they take stock of

their complete financial situation. It represents a teachable moment in financial

literacy, which should not be lost. Instead, we should seek to drive greater positive

benefit from that moment. Today taxpayers can choose to split their tax refund up

It is imperative, then,

to three ways by direct deposit when filing their returns. Affirmative initiatives

that any comprehensive should seek to help make opening a 529 Education Plan for a child, or an IRA for

overhaul of the federal retirement easier and more understandable. Even a small percentage of such sav-

ings from the average tax refund could make a real difference over time. We

tax system not make

should be encouraging citizens to pay more attention to their personal financial

the code even bigger health before and after taxes, not less.

and more complicated.

PPI supports a real drive to truly simplify our tax system, not a fig leaf. Not only

would a simpler code reduce red tape and save taxpayers hours of wasted time

pouring over forms and filing multiple documents and at multiple times and plac-

es, it would also level the playing field, create a better economic environment for

businesses of all shapes and sizes, maintain progressivity, and raise revenues for

both deficit reduction and urgent investments in our nation’s future.

If Congress and the Administration are serious about simplifying the tax code for

the vast majority of taxpayers, tax reform must achieve the following goals:

1. Promote economic efficiency and growth. We need a tax code that

allocates personal and business investment more efficiently, into activi-

ties that will create new jobs and companies. Pro-growth tax reform will

help us speed economic recovery, bring unemployment down, and shrink

the national debt. Many economists believe that reform plans that close

PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE | POLICY BRIEF 3

tax incentives and lower rates (so long as they do not add to the deficit)

can substantially improve economic growth. For example, some studies

have suggested that the last major tax reform in 1986 added 1 percent to

GDP.3 And the Joint Committee on Taxation has determined that the ef-

fect of generic base-broadening reforms to the individual code (and cor-

porate side if Congress was so inclined), could increase national output by

anywhere from 1.2 percent to 2.0 percent in the second five years after

enactment.4

2. Reduce the number of tax incentives to lower rates and rebuild

the nation’s revenue base. The tax code now contains more than $1

trillion in tax incentives. Many economists believe tax breaks distort eco-

nomic behavior and misallocate investment. Furthermore, many of these

incentives are simply a form of spending. The Simpson-Bowles plan, the

Rivlin-Domenici Commission, and the Wyden-Coats legislation have all

suggested cutting all or many of the tax incentives currently embedded in

the code and use the savings to lower marginal income rates and to cut

the deficit. Others, like House Budget Chairman Paul Ryan have proposed

similar ideas.

Each tax loophole is fiercely guarded by the special interests who benefit

from it. Closing tax breaks en masse will not be easy, but it is essential

both to lower tax rates for middle class families today, and to whittle

down public debts that imply crippling tax burdens on tomorrow's tax-

payers—aka our children.

Of course it is naïve to think that any tax reform plan would eliminate

every tax preference. The Modified Zero Plan proposed by the Simpson-

Bowles Commission in fact included a number of tax incentives, some al-

tered and some not. But even with those incentives added back in, the

modified Zero plan would cut the deficit by $1 trillion, lower the top rate

to 29 percent, cut the corporate tax rate, and move the U.S. to a territorial

tax system, so that over $1 trillion currently held by U.S. corporations

overseas could be brought back home to create jobs here in this country.

Of course, elected officials may have other good reasons for preserving

some tax breaks. For example, policymakers might want to maintain cer-

tain tax incentives for industries that won’t benefit from a lower corporate

tax rate or moving to a territorial system. But these choices should be

made in the overall context of lowering marginal rates and hitting certain

revenue targets.

3. Maintain Progressivity. Most tax incentives in the code today make it

less progressive, not more. The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a ma-

jor exception. This is true for a number of reasons, including that higher

earners participate more in tax-favored activities (like retirement savings

and mortgages) and are more likely to be able to itemize their deductions.

PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE | POLICY BRIEF 4

In addition, for many tax expenditures, the more you earn the more you

get; someone at the 15 percent rate gets a 15 cent subsidy for spending a

dollar on the same activity for which a high earner may get a 35 cent sub-

sidy.

An analysis from the Tax Policy Center has found that the top quintile

pays 11 percent less of their income in taxes thanks to tax expenditures,

while the bottom quintile pays only 6.5 percent less. If you exclude the ef-

fects of the child tax credit and EITC, the bottom quintile pays only 1 per-

cent less as a result of tax incentives, compared to 11 percent at the top.5

Pro-growth tax reform

What this means is that eliminating many tax incentives and using the

will help us speed savings for lower rates, can, in conjunction with maintaining (and maybe

economic recovery, even expanding) the EITC, maintain or improve progressivity in the tax

code.

bring unemployment

down, and shrink the 4. Reduce Errors and Avoidance. Tax law complexity often leads to

perverse results. On the one hand, taxpayers who honestly seek to comply

national debt. with the law often make inadvertent errors, causing them to either over-

pay their tax or become subject to IRS enforcement action for mistaken

underpayments. On the other hand, sophisticated taxpayers often find

loopholes that enable them to reduce or eliminate their tax liabilities.

And, all this complexity has contributed to the Federal net tax gap, which

now totals $385 billion, according to the Internal Revenue Service.6

Besides eliminating tax incentives, there are additional ways to clean up

the federal tax code. A number of tax credits phase-out across different

income ranges, so that claiming each credit requires a separate worksheet

and tax calculation. The phase outs also create hidden taxes over the

phase-out range and diminish the effectiveness of the credits in encourag-

ing the very activities they are designed to spur.

Another reform that PPI has long championed is to consolidate redun-

dant tax incentives, such as tax breaks for retirement and higher educa-

tion. In a number of areas, numerous provisions—each with slightly dif-

ferent rules-applies to the same general activity. These technical differ-

ences in real life tax situations touch so many lives (retirement and edu-

cation) but the choices are mind-numbing for most people. Coordinating

or consolidating these provisions would simplify taxes, reduce confusion,

and increase take-up rates for those healthy economic behaviors Congress

is seeking to encourage. Presently, there are some 14 different incentives

for college, 11 types of IRAs, and 3 major incentives to help parents defray

the cost of raising children.7 Such complexity works against the achieve-

ment of the intended objectives. Common sense simplification would

make tax reform work for average working families.

Tax simplification has been labeled one of the most effective ways of clos-

ing the tax gap. The tax gap is defined as the difference between what is

PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE | POLICY BRIEF 5

owed in taxes and what is not collected. According to the most recent IRS

estimate, the “net tax gap” is $385 billion annually. Generally speaking

there are three ways to reduce the tax gap:

First, hire more IRS enforcement personnel. According to Internal Reve-

nue Service internal studies, each dollar spent on an additional examiner

brings in on average 4 to 5 dollars of additional revenue.8 But given the

recent IRS scandal and our nation’s general contempt for the IRS, this

proposal is a political non-starter.

Second, increase the amount of third party reporting. Unlike wages paid

by an employer, not all forms of income are reported by a third party.

However, much has been done to increase third party reporting in recent

years and a number of obstacles exist to further reforms. But there is still

more that could be achieved by applying modern data-driven innovation

to improve the quality of returns. Government needs more complete and

accurate returns to help close the tax gap. Today many taxpayers can al-

ready electronically download financial information such as W-2s and

1099s directly into their tax returns from their original sources, such as

payroll service providers and financial institutions. Such modern data-

driven innovation should be the standard way most returns are prepared

and filed, delivering higher quality returns, with validated data and tax-

payer identity. Government should work with the private sector, much as

it did in creating the IRS Free File program, to leverage private sector in-

vestment and innovation to achieve a leap forward in tax return accuracy

and completeness, without adding new costs to IRS budgets.

Third, radically simplify the tax code. According to the General Account-

ing Office (GAO), “a broader opportunity to address the tax gap involves

simplifying the Internal Revenue Code, as complexity can cause taxpayer

confusion and provide opportunities to hide willful noncompliance. Fun-

damental tax reform could result in a smaller tax gap if the new system

has fewer tax preferences or complex tax code provisions, reducing IRS’s

enforcement challenges and increasing public confidence in the fairness

of the tax system.”9

Making taxes simpler would probably raise compliance rates, by reducing

both inadvertent and intentional nonpayment of taxes and illegal tax eva-

sion. To some (uncertain) extent, people do not pay taxes because they do

not understand the tax law. Clarifying and simplifying tax rules can only

help to make people understand the tax law better and would likely make

it easier to enforce the law as well. Evidence also suggests that people are

more likely to evade taxes that they consider unfair. People who cannot

understand tax rules may also question the fairness of the tax system and

feel that others are reaping more benefits than they are. This may make

them more likely to evade taxes.

PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE | POLICY BRIEF 6

Former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, in testimony before the Joint

Economic Committee in early 2007, listed assuring the fair collection of

taxes as the first of three policy recommendations to help the middle

class. He estimated that making a serious assault on the tax gap could

raise about $50 billion per year.10 Even more skeptical analysts

acknowledge simplification could raise some additional revenue.11

5. Better Align State and Federal Rules. One tax simplification con-

Clarifying and cept that has been largely overlooked by national policymakers, in large

simplifying tax rules can part because of the complex issues of federalism that are involved, is the

growing divergence between federal and state tax systems and rules.

only help to make

people understand the Forty-three states and the District of Columbia impose individual income

taxes. The definition of taxable income varies by state (for example, New

tax law better and

Hampshire and Tennessee tax only income from dividends and interest),

would likely make it but most states generally follow the federal definition, except that taxpay-

easier to enforce the ers may not deduct state income taxes paid.

law as well. However, a growing number of states apply different rules than the Inter-

nal Revenue Service for other types of income and have differing tax

rates. Nine states apply a single tax rate to all incomes, while the rest have

multiple tax brackets and rates. Top marginal rates for state income tax in

2008 ranged from 3 percent in Illinois to 10.3 percent in California.12

For a company, or an individual who conducts business in a number of

states, the growing divergence between federal and state rules exacer-

bates the complexity of filing taxes.

While federal tax reform is probably a heavy enough lift for this Congress,

simplification will never be maximized unless federal and state govern-

ments can come together to better align their tax systems so as to reduce

paperwork, streamline the filing process, and create less opportunity for

tax arbitrage. That is why federal tax reform legislation should begin the

process for a better coordination of federal and state tax rules and proce-

dures.

Conclusion

Simplicity and its many benefits are often overlooked in the tax reform debate,

which typically centers on economic and redistributive issues. Simplification

should be considered a goal of equal importance and should be made a funda-

mental test of comprehensive tax reform. A democracy should strive to make tax

policy transparent and user-friendly to ordinary citizens, so that it becomes an

instrument for promoting common prosperity rather than special privilege.

PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE | POLICY BRIEF 7

Fortunately, the good news is that policymakers do not have to choose among

economic growth, progressivity, and simplification when it comes to tax reform.

There are a number of plans that would incorporate all three principles and would

put our nation on a path to prosperity for everyone, not just a select few. There is

a moment of opportunity in this Congress and this Administration to do great

good in making our tax system more rational and understandable and effective.

We need to seize the moment.

Endnotes

1 “2012 Annual Report to Congress,” National Taxpayers Advocate,

2 Ibid.

3 Kevin Hassett, American Enterprise Institute.

4“Macroeconomic Analysis Of A Proposal To Broaden The Individual Income Tax Base And Lower

Individual Income Tax Rates,” Joint Committee on Taxation, December, 2006.

5“Actually, comprehensive tax reform can be progressive,” Committee for a Responsible Federal

Budget, April 15, 2011, http://crfb.org/blogs/actually-comprehensive-tax-reform-can-be-progressive.

6“IRS Releases New Tax Gap Estimates,” Internal Revenue Service, last modified April 9, 2013,

http://www.irs.gov/uac/IRS-Releases-New-Tax-Gap-Estimates;-Compliance-Rates-Remain-

Statistically-Unchanged-From-Previous-Study.

7Margot Crandall-Hollick, “Higher Education Tax Benefits: Brief Overview and Budgetary Effects,”

Congressional Research Service, March 12, 2013, http://assets.opencrs.com/rpts/R41967_20130312.pdf.

8Eric Toder, “Tax Vox Proposal: Hire More IRS Agents to Close Tax Gap,” Tax Policy Center,

http://www.pappastax.com/index.php/2009/01/tax-vox-proposal-hire-more-irs-agents-to-close-tax-

gap/.

9 “2013 High Risk Report”, General Accounting Office, February, 2013.

10Eric Toder, “Reducing the Tax Gap: The Illusion of Pain-Free Deficit Reduction”, Urban Institute

and Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, July, 2007.

11 Ibid.

12“State and Local Tax Policy: How do state and local income taxes work?,” Tax Policy Center,

http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/state-local/specific/income.cfm.

About the Author

Paul Weinstein Jr. is an eight-year veteran of the Clinton Administration and

served as senior advisor to the Simpson-Bowles Commission. He is currently a

senior fellow at the Progressive Policy Institute and directs the Graduate Program

in Public Management at The Johns Hopkins University.

About the Progressive Policy Institute

The Progressive Policy Institute (PPI) is an independent research institution that

seeks to define and promote a new progressive politics in the 21st century.

Through research and policy analysis, PPI challenges the status quo and advo-

cates for radical policy solutions.

PROGRESSIVE POLICY INSTITUTE | POLICY BRIEF 8

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

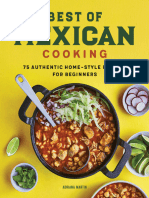

- Best of Mexican CookingDocument154 pagesBest of Mexican CookingJuanNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Weidner - Fulcanelli's Final RevelationDocument22 pagesWeidner - Fulcanelli's Final Revelationjosnup100% (3)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Companion Study Guide: 15 LessonsDocument124 pagesCompanion Study Guide: 15 LessonsLuisk MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Mechanic of Solid and Shells PDFDocument521 pagesMechanic of Solid and Shells PDFKomarudinNo ratings yet

- Zhuangzi's Butterfly DreamDocument4 pagesZhuangzi's Butterfly DreamUnnamed EntityNo ratings yet

- Highland GamesDocument52 pagesHighland GamesolazagutiaNo ratings yet

- Audit For Private Companies What Do We KnowDocument21 pagesAudit For Private Companies What Do We KnowErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- ch09 180320122027 PDFDocument69 pagesch09 180320122027 PDFErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Judicial & Bar CouncilDocument3 pagesJudicial & Bar Councilmitch galaxNo ratings yet

- FortiNAC High AvailabilityDocument55 pagesFortiNAC High Availabilitydropbox100% (1)

- Science, Technoloy and Society Prelim ExamDocument14 pagesScience, Technoloy and Society Prelim ExamIman Official (Em-J)No ratings yet

- ACAINvs CADocument2 pagesACAINvs CAabogada1226No ratings yet

- Soal AKLDocument3 pagesSoal AKLErica Lesmana100% (1)

- Shadowcrew: Click To ContinueDocument16 pagesShadowcrew: Click To ContinueErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Case Shrinking Potato ChipDocument1 pageCase Shrinking Potato ChipErica Lesmana0% (1)

- COSO Internal Controls Sustainability91117Document55 pagesCOSO Internal Controls Sustainability91117Erica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Welcome To My Presentation: Md. Asibur Rahman ID 05 051Document18 pagesWelcome To My Presentation: Md. Asibur Rahman ID 05 051Erica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Shadowcrew: Click To ContinueDocument16 pagesShadowcrew: Click To ContinueErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Data Driven Collection-PlayfulDocument14 pagesData Driven Collection-PlayfulErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence & Machine LearningDocument82 pagesArtificial Intelligence & Machine LearningErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Sustainability Reporting: The Role of "Search", "Experience" and "Credence" InformationDocument13 pagesSustainability Reporting: The Role of "Search", "Experience" and "Credence" InformationErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Acta Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section C - Food EconomicsDocument9 pagesActa Agriculturae Scandinavica, Section C - Food EconomicsErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- Jawabab MK WayanDocument1 pageJawabab MK WayanErica LesmanaNo ratings yet

- 6 Tissue Terrains ColorDocument1 page6 Tissue Terrains Colorஆ.க.கோ. இராஜேஷ்வரக் கோன்No ratings yet

- LESSON PLAN World Religion Week 6Document3 pagesLESSON PLAN World Religion Week 6VIRGILIO JR FABINo ratings yet

- Advanced Fabric Structure and ProductionDocument15 pagesAdvanced Fabric Structure and ProductionmohsinNo ratings yet

- Mass GuideDocument13 pagesMass GuideDivine Grace J. CamposanoNo ratings yet

- (Computer Science and Engineering) : University of Engineering & Management (UEM), JaipurDocument35 pages(Computer Science and Engineering) : University of Engineering & Management (UEM), JaipurDeepanshu SharmaNo ratings yet

- Noda 1996Document5 pagesNoda 1996Enthroned BlessedNo ratings yet

- UNM Environmental Journals: Ashary Alam, Muhammad Ardi, Ahmad Rifqi AsribDocument6 pagesUNM Environmental Journals: Ashary Alam, Muhammad Ardi, Ahmad Rifqi AsribCharles 14No ratings yet

- Mat Lab Interview QuestionsDocument2 pagesMat Lab Interview QuestionsSiddu Shiva KadiwalNo ratings yet

- Desert RoseDocument2 pagesDesert RoseGADAANKITNo ratings yet

- Matlab TutorialDocument182 pagesMatlab TutorialSajjad Pasha MohammadNo ratings yet

- Site Analysis Requirements PDFDocument24 pagesSite Analysis Requirements PDFmuthukumar0% (1)

- High School Religious Education Curriculum Framework From USCCBDocument59 pagesHigh School Religious Education Curriculum Framework From USCCBBenj EspirituNo ratings yet

- Eight Hundred Meters From The Hypocenter - Student ExampleDocument4 pagesEight Hundred Meters From The Hypocenter - Student Exampleapi-452950488No ratings yet

- BMI FormulasDocument2 pagesBMI Formulasbarb201No ratings yet

- Senate - Community Projects 2009-10Document98 pagesSenate - Community Projects 2009-10Elizabeth Benjamin100% (3)

- Dizon v. Court of AppealsDocument9 pagesDizon v. Court of AppealsAgus DiazNo ratings yet

- Maximus Price ResumeDocument2 pagesMaximus Price Resumeapi-491233681No ratings yet

- Handbook 2018 v2 15Document20 pagesHandbook 2018 v2 15api-428687186No ratings yet

- SafewayDocument7 pagesSafewayapi-671978278No ratings yet