Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 11

Uploaded by

Sheilla Tania Marcelina0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesSTRENGTHENING QUALITY MIDWIFERY EDUCATION FOR 2030 - WHO UNFPA UNICEF PART 11

Original Title

STRENGTHENING QUALITY MIDWIFERY EDUCATION FOR 2030 - WHO UNFPA UNICEF PART 11

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSTRENGTHENING QUALITY MIDWIFERY EDUCATION FOR 2030 - WHO UNFPA UNICEF PART 11

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

6 views3 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 11

Uploaded by

Sheilla Tania MarcelinaSTRENGTHENING QUALITY MIDWIFERY EDUCATION FOR 2030 - WHO UNFPA UNICEF PART 11

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

2.8.

2 Variable quality in education and

training standards

Published literature on midwifery skills

education describes a range of health workers,

both professional and non-professional, who are

providing some midwifery skills (14, 55). Among

the various health workers described, there is a

lack of consistency in education programmes

(56) and in the use of the term “midwife” (56).

This means it is not clear which of the health

workers are educated and trained to

international-standard midwifery (16). Nursing

and midwifery education is often combined,

rendering midwifery skills education and training

invisible in policy, as well as in practice (57).

Since 2004 there has been a focus on measuring

skilled birth attendants (SBAs) in LMICs (58).

However, the SBA indicator does not reflect

quality of childbirth care, and may give the false

impression that progress in access to quality

care is being made (4). The definition of the SBA

has recently been updated and since 2018

describes “skilled health personnel (competent

health care professionals) providing care during

childbirth” (58). While contributing to the overall

decrease in mortality, the training, regulation

and deployment of SBAs with a specific focus

on childbirth has varied widely across countries,

with uneven levels of proficiency and regulatory

support (2, 59, 60).

Not all SBAs provide all areas of maternal and

newborn care or are trained to deal with

unexpected complications (60, 61). In a recent

scoping review, only 15% of those working as

SBAs were reported to identify themselves as

“midwives”, and it is not clear whether those

who described themselves as such were

educated to international standards (62).

“In a scoping review of the

health personnel considered

SBAs in 36 LMICs, a total of 102

unique cadres names were

identified. Of the cadres

included, 16% represented

doctors, 16% were nurses, and

15% were midwives. There was

substantial heterogeneity

between and within countries on

the reported definition of an

SBA and the education, training,

skills and competencies that they

were able to perform.”

Hobbs et al. PLoS ONE (62)

2.8.3 Educators lack skills, access to

clinical sites and training materials

Early results from a WHO survey of midwifery

educators in five WHO regions provide a stark

picture of the realities of constrained teaching

and learning environments . Educators are more

confident with theoretical classroom teaching

than clinical teaching. Many are unable to

access clinical settings, or simulation tools, to

support competency-based education with

women and babies.

Large gaps in educator skills are evident,

including basic postnatal care of women and

newborns, and the provision of family planning.

Few educators reported having the education

materials needed. The survey further highlighted

inconsistencies in the content and duration of

education courses, variations in the

competencies required, as well as the plethora

of pathways to becoming a “midwife”, indicating

a wide variation in the standard of education

and training, and thereby variations in the

quality of care provided.

You might also like

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 22Document3 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 22Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 20Document4 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 20Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 20Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 20Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 21Document4 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 21Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 21Document4 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 21Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 19Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 19Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 18Document3 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 18Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 14Document5 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 14Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 17Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 17Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 16Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 16Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 13Document1 pageStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 13Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 15Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef 15Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 12Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 12Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 10Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 10Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 8Document3 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 8Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 4Document4 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 4Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 7Document3 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 7Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 5Document5 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 5Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 8Document3 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 8Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 6Document3 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 6Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 3Document4 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 3Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 2Document2 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education For 2030 - Who Unfpa Unicef Part 2Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Strengthening Quality Midwifery Education Part 1Document10 pagesStrengthening Quality Midwifery Education Part 1Sheilla Tania MarcelinaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Comprehensive Review For CorporationDocument14 pagesComprehensive Review For CorporationJoemar Santos Torres33% (3)

- MandaluyongDocument33 pagesMandaluyongapi-3806163100% (2)

- LatihanDocument3 pagesLatihanarif100% (1)

- Midem 2012 (Cannes, 28-31 Jan) - Conference ProgrammeDocument56 pagesMidem 2012 (Cannes, 28-31 Jan) - Conference ProgrammeElJay AremNo ratings yet

- All You Need To Know About Track Visitor PermitsDocument2 pagesAll You Need To Know About Track Visitor PermitsGabriel BroascaNo ratings yet

- SimulcryptPrimer PDFDocument5 pagesSimulcryptPrimer PDFTechy GuyNo ratings yet

- Wassel Mohammad WahdatDocument110 pagesWassel Mohammad WahdatKarl Rigo Andrino100% (1)

- Ambush MarketingDocument18 pagesAmbush Marketinganish1012No ratings yet

- ISBT ReportDocument34 pagesISBT ReportRajat BabbarNo ratings yet

- Book of Mormon: Scripture Stories Coloring BookDocument22 pagesBook of Mormon: Scripture Stories Coloring BookJEJESILZANo ratings yet

- Economics in Education: Freddie C. Gallardo Discussant Ma. Janelyn T. Fundal ProfessorDocument14 pagesEconomics in Education: Freddie C. Gallardo Discussant Ma. Janelyn T. Fundal ProfessorDebbie May Ferolino Yelo-QuiandoNo ratings yet

- ICT - Rice Farmers - KujeDocument12 pagesICT - Rice Farmers - KujeOlateju OmoleNo ratings yet

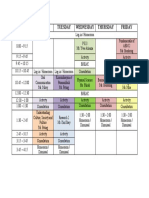

- Schedule - Grade 12 St. Ignatius de LoyolaDocument1 pageSchedule - Grade 12 St. Ignatius de LoyolaChennie Glenn Bonagua HernandezNo ratings yet

- Passenger Locator Form: AmberDocument4 pagesPassenger Locator Form: AmberRefik SasmazNo ratings yet

- Become A Partner Boosteroid Cloud Gaming PDFDocument1 pageBecome A Partner Boosteroid Cloud Gaming PDFNicholas GowlandNo ratings yet

- Tiqqun - What Is Critical MetaphysicsDocument28 pagesTiqqun - What Is Critical MetaphysicsBrian GarciaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2 - Hospitality IndustryDocument49 pagesLesson 2 - Hospitality Industrymylene apattadNo ratings yet

- 03-F10 Planned Job ObservationDocument1 page03-F10 Planned Job ObservationSn Ahsan100% (1)

- PowerUp Prelims Test Series - Batch 8finalDocument12 pagesPowerUp Prelims Test Series - Batch 8finalmuthumaniNo ratings yet

- Tyre Air Pressure 2010 enDocument172 pagesTyre Air Pressure 2010 enbruteforce2000No ratings yet

- Language ChangeDocument10 pagesLanguage ChangeDiana Ari SusantiNo ratings yet

- Submitted To:-Presented By: - Advocate Hema Shirodkar Ankit Gupta Sourabh KhannaDocument10 pagesSubmitted To:-Presented By: - Advocate Hema Shirodkar Ankit Gupta Sourabh KhannaAnkit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Test For The Honors ClassDocument9 pagesTest For The Honors Classapi-592588138No ratings yet

- Annexure-I - ISO 9001 2015 CHECKLIST For OfficesDocument1 pageAnnexure-I - ISO 9001 2015 CHECKLIST For OfficesMahaveer SinghNo ratings yet

- 001) Each Sentence Given Below Is in The Active Voice. Change It Into Passive Voice. (10 Marks)Document14 pages001) Each Sentence Given Below Is in The Active Voice. Change It Into Passive Voice. (10 Marks)Raahim NajmiNo ratings yet

- What Is Theology?Document4 pagesWhat Is Theology?Sean WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Pilar, BataanDocument2 pagesPilar, BataanSunStar Philippine NewsNo ratings yet

- Bill PranayDocument1 pageBill PranaySamaj KalyanNo ratings yet

- 21 ST Century Lit Module 3Document6 pages21 ST Century Lit Module 3aljohncarl qui�onesNo ratings yet

- Personal Data SheetDocument4 pagesPersonal Data SheetEdmar CieloNo ratings yet