Professional Documents

Culture Documents

982 Full PDF

982 Full PDF

Uploaded by

syahputriOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

982 Full PDF

982 Full PDF

Uploaded by

syahputriCopyright:

Available Formats

EXPERIENCE AND REASON—Briefly Recorded

‘‘In Medicine one must pay attention not to plausible theorizing but to experience and reason together. . . . I

agree that theorizing is to be approved, provided that it is based on facts, and systematically makes its

deductions from what is observed. . . . But conclusions drawn from unaided reason can hardly be serviceable;

only those drawn from observed fact.’’ Hippocrates: Precepts. (Short communications of factual material are

published here. Comments and criticisms appear as letters to the Editor.)

Bullous Myringitis: A Case-Control onto portions of the external auditory canal immedi-

ately adjacent to the TM.3 Bullae involving the TM

Study should be distinguished from bullae involving only

the ear canal; the latter are a form of external otitis

ABSTRACT. Prior studies have shown that bullous media (OM). It was once thought that Mycoplasma

myringitis (BM) accounts for <10% of acute otitis media

(AOM) cases, and that the distribution of viral and bac- pneumoniae infection was an important cause of

terial pathogens in BM is similar to that in AOM without BM,7–10 but this idea was later invalidated.11–13 In an

BM, except for a relative increase in the proportion of extensive review of the literature, Merrifield11 iden-

Streptococcus pneumoniae in BM. We studied 518 cases of tified reports of 612 patients with documented M

AOM in children aged 6 months to 12 years. Using tele- pneumoniae infection, and among these 37 patients

otoscopy to assist the diagnosis, we identified 41 cases had ear involvement (6 with BM). In reported cases

(7.9%) with BM. Children who had AOM with BM were of BM, 1 of 16 grew M pneumoniae. Of 858 attempts to

older than AOM patients without BM (median age: 4.3 isolate M pneumoniae from non-BM cases of AOM,

years vs 18 months). We compared 41 cases of AOM with

none grew M pneumoniae from the middle ear fluid.

BM to 41 control cases of age-, race-, and gender-matched

AOM patients without BM. When compared with this Merrifield concluded that: “The tympanic mem-

matched control group, children with BM had more se- brane’s ability to form blisters appears to be a non-

vere symptoms at the time of diagnosis and were more specific reaction. Bullous myringitis is merely acute

likely to have bulging of the tympanic membrane in the otitis media with blisters within the layers of the

quadrants that were not obscured by the bulla. Children eardrum. There is little evidence that otitis media,

with AOM and BM may require aggressive pain manage- with or without bullous myringitis, is caused by

ment. Although parents and clinicians may agree that a Mycoplasma pneumoniae.”

watchful waiting approach is appropriate for older chil- Studies have shown that BM accounts for ⬍10% of

dren with mild AOM, children experiencing painful

AOM cases, and that viral and bacterial pathogen

AOM with BM may not be successful candidates for a

watchful-waiting approach, because parents may resist distribution in BM is similar to that in AOM without

postponement of antibiotic therapy in children who are BM, except for a relative increase in the proportion of

more symptomatic. Pediatrics 2003;112:982–986; acute oti- Streptococcus pneumoniae in ears with bullae.14,15 Al-

tis media, diagnosis, bullous myringitis, case-control, though descriptive studies indicate that BM is a se-

child. vere form of AOM, no quantitative information on

the clinical severity of illness has been reported in

ABBREVIATIONS. BM, bullous myringitis; TM, tympanic mem- AOM patients with and without BM. In this case-

brane; AOM, acute otitis media; OM, otitis media; OM-3, otitis control study, we compared the clinical severity of

media 3-item questionnaire: UTMB, University of Texas Medical AOM with or without BM, based on parent’s percep-

Branch at Galveston; OS-8; otoscopy score, 8 grades. tion of illness, body temperature, tympanogram, and

otoscopic findings.

B

ullous myringitis (BM) is an acutely painful

condition of the ear characterized by bulla for- METHODS

mation on the tympanic membrane (TM). BM

was described in early articles as occurring in asso- Subjects

ciation with acute otitis media (AOM).1,2 Previous We prospectively recruited a convenience sample of children

with symptomatic AOM (aged 6 months to 12 years) from our

studies indicated that BM is often associated with pediatric clinic. Patients were initially identified if they had signs

fever3 and considerable pain,3,4 possibly because the and symptoms of AOM as described below. Patient enrollment

blisters of BM may occur between the richly inner- occurred between May 2000 and August 2002. Verbal assent was

vated outer epithelium and middle fibrous layers of obtained from parents as approved by our institutional review

the TM.5,6 Bullae involving the TM may also extend board. Oral, rectal, or axillary body temperatures were measured

by electronic thermometer. All oral and rectal temperatures were

corrected to axillary (skin) temperature for the purpose of com-

Received for publication Dec 13, 2003; accepted Jun 3, 2003. parability. Parents completed a demographic questionnaire on

Davis C. Teichgraeber, BA, is a third-year medical student at the University risk factors such as duration of breastfeeding (months), day care

of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, Galveston, Texas. attendance (not attending, 1–20 hours/week, 21– 40 hours/week,

Reprint requests to (D.P.M.) Department of Pediatrics, Primary Care Pavil- ⬎40 hours/week), passive tobacco smoke exposure at home (not

ion, 400 Harborside Dr, Rm 2.701, Galveston, TX 77555-1119. E-mail: exposed or exposed), and prior history of ear infections (number

david.mccormick@utmb.edu of infections). To be included in the study, children were required

PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 2003 by the American Acad- to have 1) symptoms, 2) evidence of acute inflammation of the TM,

emy of Pediatrics. and 3) middle-ear effusion.

982 PEDIATRICS Vol. 112 No. 4 October 2003

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on November 3, 2019

Symptoms private, 13% other) who agreed to grade, by order of severity, a set

of high-quality prints of the OS-8 photoset displayed in random

All subjects had acute onset of symptoms, signs of TM inflam-

order. Ninety-five of 122 pediatricians responded to the survey.

mation, and presence of middle-ear fluid.16 Because a valid and

standardized severity scoring method was not available for AOM, Statistical analysis of the results confirmed good agreement with

we asked parents to report the severity of their child’s ear infection our predetermined levels of severity (R ⫽ 0.841; P ⬍ .001; N ⫽ 759

symptoms on a questionnaire (OM-3) that listed the 3 acute illness comparisons; Spearman).

items from Rosenfeld’s OM health status questionnaire,17 origi- Once OS-8 had been developed, investigators were trained to

nally designed for children with chronic middle-ear effusion. The grade the TMs using photosets and live ears of children with AOM

OM-3 questionnaire consisted of the following 3 items: “During until their independent inter-observer agreements reached an ac-

the past 24 hours, has your child experienced any of the following ceptable level (Kappa ⬎0.6). The trained investigators then per-

attributable to ear infection a) physical suffering such as ear pain, formed otoscopic examinations on the subjects in this study, and

ear discomfort, high fever, or poor balance, b) emotional distress graded the TMs using OS-8. Whenever possible, diagnosis was

such as irritability, frustration, sadness, restlessness, or poor ap- aided by photographs of subjects’ TMs taken with the tele-oto-

petite, and c) limitation in activity such as playing, sleeping, doing scope. In accordance with expert panel criteria,24 TM opacification

was required for inclusion in the study (OS-8 score ⱖ4 in at least

things with friends/family, attending school or day care.” Parents

1 TM). Because blood vessel dilatation is a manifestation of in-

indicated the severity of each of the 3 OM-3 items by marking a

flammation, we excluded children from the study if they had no

7-point Likert scale from 1 (“not present, not a problem”) to 7

evidence of TM hyperemia. When photographs were available, the

(“extreme problem”). The duration of time between the onset of

bullae were later inspected to verify their color, degree of opaci-

AOM symptoms and the diagnosis was not recorded in this study.

fication, location, size, and shape. In addition, any quadrants not

OM-3 total scores were calculated as the sum of the 3 items.

occupied by a bulla were observed for the presence of bulging.

We validated OM-3 for use in children with AOM as follows: a)

6 UTMB (University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston) expert

investigators agreed on its face validity, b) OM-3 demonstrated Middle-Ear Effusion

inter-item reliability (␣ ⫽ 0.80; n ⫽ 518 children with AOM, where Tympanograms were obtained on all subjects using a Welch-

␣ reliability ⬍0.4 ⫽ poor, 0.4 – 0.75 ⫽ good, ⬎0.75 excellent), c) Allyn TM262 Auto Tymp tympanometer and were categorized

higher OM-3 total scores and physical suffering subscores were using standard criteria25 except we used a more stringent defini-

associated with greater degrees of inflammation of the TM (OM-3 tion of abnormal compliance (⬍0.2 mL.) based on results reported

total vs otoscopy score, 8 grades [OS-8], ⱕ5 or ⱖ6, P ⬍ .06; by Le et al.26 Tympanograms were classified as: normal, type A

physical suffering subscore vs OS-8 ⱕ5 or ⱖ6; P ⬍ .001; 2 test; n ⫽ (compliance ⱖ0.2 mL, ⫺100 ⬍ middle-ear pressure ⱕ ⫹50 daPa);

518), d) higher OM-3 total scores and physical suffering subscores bulging, type A⫹ (compliance ⱖ0.2 mL, middle-ear pressure ⬎

were associated with higher body temperatures, (OM-3 total score ⫹50 daPa); middle-ear effusion, type B (compliance ⬍0.2 mL); and

vs body temperature, Spearman correlation, R ⫽ 0.21; P ⬍ .0001; retracted, type C (compliance ⱖ 0.2 mL, middle ear pressure ⬍

n ⫽ 518; physical suffering subscore vs body temperature, R ⫽ ⫺99 daPa). For a diagnosis of AOM, children were required to

0.24; P ⬍ .0001; Spearman), and e) correlation between OM-3 total have evidence of middle-ear effusion by pneumatic otoscopy

score and 2 previously published symptom-severity scales: a and/or tympanometry and/or direct visualization of a fluid level.

5-item ear treatment group scale described previously18 (R ⫽ 0.66; Effusions observed in ears with a normal tympanogram were

P ⬍ .0001; n ⫽ 518; Spearman) and a previously published visual typically characterized by the presence of either: a) a fluid-filled

analog scale19,20 (R ⫽ 0.73; P ⬍ .0001; n ⫽ 518, Spearman). bulla or bullae on a hyperemic opacified TM, or b) a nonbulging

hyperemic TM that under high illumination showed a partial

TM effusion, ie, an air-fluid level (opaque fluid) or air bubble(s).

Because none existed previously, we developed, as follows, a

categorization system (OS-8) to describe the appearance of the TM Chart Review

in children with AOM.21,22 First, numerous photographs of the Charts of the cases and controls were reviewed for follow-up

TMs of children with and without AOM were obtained by our course of the illness and evidence of prior S pneumoniae heptava-

investigators using a Storz tele-otoscope (Karl Storz Imaging, Go- lent vaccine administration (Prevnar, Wyeth Laboratories, Madi-

leta, CA) through a 3.0-mm reusable speculum held in place by a son, NJ). Subjects were categorized as immunized if at least 1

Welch Allyn otoscope head (Welch Allyn, Inc, Skaneateles Falls, month had elapsed between their last immunization and enroll-

NY). Photographs were printed in glossy format using a Sony ment in the study. S pneumoniae type-specific antibody titers were

printer (Sony Electronics, Woodcliff Lake, NJ), and saved on a considered high enough to provide partial or complete protection

server for future study. if a) the first dose of vaccine was given between the ages of 2 and

The investigators studied the photographs and sorted them 12 months, and the child had received at least 3 doses, or b) if the

initially into categories from normal (no erythema, no effusion, first dose of vaccine was given between the ages of 1 and 2 years,

normal structures) to severe (erythema, effusion, opacification, and the child had received 2 doses, or c) if a single dose of vaccine

bulla formation). The investigators then used the grading scale to was given ⱖ2 years of age. Subjects were categorized as not

independently evaluate sets of photographs. At each iteration, the immunized if they had not received vaccine or had received any

investigators discussed their differences and improved on the number of doses less than the regimen described above. Children

definitions. The scale was modified repeatedly until 6 investiga- began receiving heptavalent pneumococcal vaccine in our clinic in

tors reached verbal agreement on the following 8 levels of sever- October 2000.

ity: 0 ⫽ normal, or effusion without hyperemia; 1 ⫽ hyperemia

only, no effusion; 2 ⫽ hyperemia, air-fluid level, no opacification,

meniscus noted; 3 ⫽ hyperemia, complete effusion, no opacifica- Statistics

tion; 4 ⫽ hyperemia, opacification, air-fluid level observed, no Forty-one of 518 cases of AOM were diagnosed with BM (7.9%).

bulging; 5 ⫽ hyperemia, complete effusion, opacification, and no Because the subjects with BM (median age: 4.3 years) were older

bulging; 6 ⫽ hyperemia, bulging rounded doughnut appearance than the subjects without BM (median age: 18 months), each

of TM; and 7 ⫽ hyperemia with bulla formation. TMs rated subject with BM was paired with his/her closest AOM case with-

between 2 categories were given the higher score. Because we out BM, matched by age, race, and gender. The median difference

were using very high-quality examination equipment, we were in ages between the subjects with BM and their matches was 7

often able to directly visualize bubbles or a fluid level within the weeks. We used the t test to compare total OM-3 scores of the

middle-ear space in ears categorized as grade 2 and 4, even when subjects with and without BM and the paired t test to compare

the TM was erythematous and partially opacified. Intense illumi- physical suffering scores for subjects with BM and their matches

nation was provided by a hand-held otoscope supplied with a (SAS statistical software). We used the 2 test to evaluate the

fresh halogen lamp and fully-charged nickel cadmium batteries. relation of bulla formation to categorical variables such as expo-

We also used the original Welch-Allyn reusable speculum, which sure to tobacco smoke (none vs any smokers at home), season of

we consider superior to the Welch-Allyn disposable speculum, diagnosis (November–February vs March–October), and type of

which has numerous design flaws.23 tympanogram. We used the sign test27 to compare the groups on

OS-8 was further validated as follows. At pediatric meetings we all other variables. A P value ⬍ .05 was considered to be statisti-

approached North American pediatricians (27% academic, 60% cally significant. If bilateral AOM were present, only data from the

EXPERIENCE AND REASON

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on November 3, 2019

983

worst ear (considering the OS-8 score and tympanogram) were TABLE 2. Comparison of Matched Pairs Using the Sign Test

analyzed.

Variable Number of Pairs P

RESULTS BM Case Non-BM Ties

Of 41 matched pairs, 51% were male; 39% were Had Higher Subject Had

Value Higher Value

white, 27% Hispanic, 24% black, and 10% other. Bi-

lateral AOM was present in 29% of the BM subjects Physical suffering 22 9 10 .02

and 32% of the non-BM subjects. Two of the 41 BM Body temperature 26 15 0 .06*

Hours in child care 10 7 24 ⬎.10*

cases had bilateral BM. Two of the 41 BM cases (5%) Prior AOM 17 14 10 ⬎.10*

and 5 of the 41 non-BM controls (12%) displayed a Breastfeeding history 13 13 15 ⬎.10*

normal (type A) tympanogram. Five of the BM cases

* indicates not significant.

and 1 of the non-BM cases displayed an A⫹ or

positive pressure tympanogram. These comparisons

were not statistically significant by 2 analysis (see

Table 1). Total mean OM-3 scores were 13.5 ⫾ 4.7 for

the BM cases and 12.1 ⫾ 4.1 for the non-BM controls

(P ⫽ .05). The difference in OM-3 total scores be-

tween the groups was attributable mainly to the

physical suffering subscore. The mean physical suf-

fering subscore was 4.76 in subjects with AOM and

BM, versus 4.27 in subjects with AOM and non-BM,

a difference of 0.49 units or 0.29 standard deviation

(P ⬍ .02; Table 2). BM was not associated with du-

ration of breastfeeding, day care attendance, passive

tobacco smoke exposure, or prior history of ear in-

fections. Mean skin surface body temperatures were

marginally higher in the BM group (BM subjects

mean: 36.7 ⫾ 0.83°C; non-BM subjects mean: 36.4 ⫾

0.73°C; P ⫽ .06; see Table 2). Nine subjects with BM

had ⱖ37.3°C (equivalent to 38.3 rectal temperature)

at the time of initial evaluation; 4 subjects in the

non-BM group had initial temperatures this high.

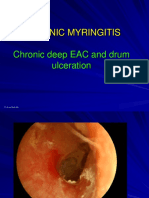

Fig 1. Left TM of a 5-year-old boy who attended day care and had

Distribution of OS-8 scores for the non-BM a history of 7 AOM episodes. The child presented with upper

matched controls was as follows: 13 with a score of 4 respiratory tract infection symptoms, cough, earache, irritability,

(32%), 11 with a score of 5 (26%), and 17 with a score decreased appetite, and restless sleep. He was afebrile. The TM

of 6 (42%). Bulging of the portions of the TM not has a small bulla in the superior quadrant. The tympanogram was

occupied by the bulla was not initially recorded for flat. Note the collection of blood in the inferior pole of the bulla.

Note 2 other areas of gross hemorrhage in the posterior superior

any subject receiving an OS-8 score of 7. However, quadrant. Also seen is the typical bicycle spoke-like distribution of

photographs were available for review in 33 subjects hyperemic capillaries on the surface of the TM. This TM shows

with AOM and BM (see Fig 1, Fig 2, and Fig 3); of some fullness as can be appreciated by the slightly rounded ap-

these 32 (97%) had a bulging TM. Only 17 of 41 (42%) pearance of the dilated capillaries supplying blood to the center of

the TM, which appears more intensely inflamed.

of the non-BM pairs had a bulging TM.

Three of the 41 cases of AOM with BM were diag-

nosed with draining OM 22 to 60 days after initial tobacco smoke exposure, attendance at child care,

evaluation. This compares with one case of draining history of prior AOM, nor season of diagnosis was

OM on the 51st day after evaluation among the related to BM.

non-BM controls. There were no differences in his-

tory of tympanostomy tube placement, failure of DISCUSSION

treatment, or relapse between the BM cases and This study presents quantitative evidence that BM

non-BM controls. Only 7% percent of the BM cases cases may have more severe symptoms than non-BM

and 10% of the non-BM matched controls had re- cases when compared against the broad spectrum of

ceived sufficient numbers of doses of heptavalent AOM observed in clinical practice. Our data agree

pneumococcal vaccine to meet criteria for partial or with prior studies showing that BM occurs more

complete protection against the strains of S pneu- commonly in older children.13 A strength of this

moniae common to children. Neither breastfeeding, study is the case-control design and the large num-

ber of nonbullous AOM subjects available for match-

TABLE 1. Tympanogram Results ing and statistical comparison with the BM subjects.

Tympanogram Classification Another strength is the quality of otoscopic exami-

nations performed by trained investigators with as-

Type A Type A⫹ Type B Type C sistance of the OS-8 scoring system and high-resolu-

BM* 2 5 32 2 tion photographs taken with the tele-otoscope (Figs

AOM no bulla* 5 1 33 2 1–3).

* indicates not significant. Because the between-group differences were small

P ⬎ .30. for OM-3 and physical suffering (⬍0.5 standard de-

984 EXPERIENCE AND REASON

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on November 3, 2019

A possible weakness of the study is the lack of data

on the validity of tympanometry for the assessment

of middle-ear effusion in AOM. We categorized tym-

panograms using methods based on articles by

Finitzo25 and Le.26 However, these authors did not

specifically study subjects with AOM, but assessed

children immediately before the insertion of pressure

equalizing tympanostomy tubes. Our study empha-

sizes the need for additional work on the reliability

of tympanometry as a specific predictor of middle-

ear effusion in AOM.

We and others have previously shown that a mid-

dle-ear culture positive for S pneumoniae is often

associated with more severe clinical symptoms of

AOM, higher levels of inflammatory mediators,

and/or otoscopic evidence of a more inflamed

TM.28 –30 The present study provides no bacteriologic

data; however, others have shown that S pneumoniae

is more often the etiologic agent in BM than in AOM

Fig 2. Right TM of same child and same episode as in Fig 1. Three without BM.14,15 Palmu14 detected S pneumoniae in

bullae lie side by side adjacent to the malleus, which is not visible.

The TM shows significant bulging. The tympanogram was flat. 32.4% of ears with BM versus 14.5% of ears with no

Bullae are filled with opaque, yellowish fluid. Some hemorrhage is BM. Coffey1 cultured S pneumoniae in 7 of 10 ears

also noted. with BM. Rosenblut15 detected S pneumoniae in 20 of

27 (74%) cases with BM compared with 43 of 143

(30%) cases of AOM without BM (P ⬍ .001). It should

be noted that the children with BM in our study were

older than the others, and many had not had an

opportunity to receive the heptavalent pneumococ-

cal vaccine. We speculate that S pneumoniae might be

responsible for the greater degree of inflammation

and more severe symptoms in some of our cases as

well.

Clinicians have been encouraged to consider an

option of watchful waiting using symptom manage-

ment without prescribing immediate antibiotics

for children with mild AOM, because the literature

indicates that most such children will recover with-

out antimicrobial treatment.31–32 This approach

would facilitate the judicious use of antimicrobial

agents currently recommended by the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention.33 Some children

experiencing painful AOM with BM may not be

successful candidates for a watchful-waiting ap-

Fig 3. Right TM with a large bulla occupying the inferior quad- proach to treatment, because parents may resist

rants in a 3-year-old boy with a temperature 38.5°C who attended postponement of antibiotic therapy in children who

day care and presented with cough and ear pain. He had a history

of 7 episodes of AOM. The tympanogram revealed an abnormal

are more symptomatic. If antibiotic treatment is ini-

compliance and a normal gradient. Note the distinct margins tiated for such children, caution should be used in

between the bulla and the TM. The TM is bulging and mostly pale, selecting the appropriate agent. The literature indi-

with a few small capillaries noted, except for the area of the pars cates that S pneumoniae is more often the pathogen

flaccida, which is intensely hyperemic. responsible for AOM with BM, and this organism

may be resistant to penicillin and other antibiotics in

communities where antibiotics have been used ex-

viation), additional work will be needed to verify the tensively.

clinical significance of our findings. However, our

findings do support published clinical observations CONCLUSIONS

in which authors have described BM as having more When compared with children with AOM without

severe symptoms than AOM without bulla forma- BM, children with AOM and BM were older, had

tion. These results are also supported by the finding higher symptom scores, and had more severe oto-

that 97% of the TM photographs from the subjects scopic findings in the portions of the TM not occu-

with BM showed bulging of the portions of the TM pied by the bulla. Because some children with BM

that were not obscured by the bulla, whereas only may have significant pain at the time of initial eval-

42% in the control group showed bulging of the TM. uation, the clinician should pay special attention to

Bulging is generally considered to be a more severe pain management in such cases. Children with pain-

presentation of AOM. ful BM may not be successful candidates for a watch-

EXPERIENCE AND REASON

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on November 3, 2019

985

ful-waiting approach, because parents may resist etiology of acute otitis media in Chilean children. Pediatr Infect Dis J.

2001;20:501–507

postponement of antibiotic therapy in children who 16. Heikkinen T, Ruuskanen O. Signs and symptoms predicting acute otitis

are more symptomatic. media. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:26 –29

17. Rosenfeld RM, Goldsmith AJ, Tetlus L, Balzano A. Quality of life for

David P. McCormick, MD children with otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:

Kokab A. Saeed, MD 1049 –1054

Carmen Pittman, BA 18. McCormick DP, Lim-Melia E, Saeed KA, Baldwin CD, Chonmaitree T.

Division of General Academic Pediatrics Otitis media: can clinical findings predict bacterial or viral etiology?

University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:256 –258

Galveston, TX 77555-1119 19. Whaley L, Wong DL. Nursing Care of Infants and Children. 3rd ed. St

Louis, MO: CV Mosby Company; 1987

20. Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales.

Constance D. Baldwin, PhD Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14:9 –17

Division of Education/Research 21. McCormick DP, Friedman N, Chonmaitree T, Saeed K, Baldwin CD,

University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston Klimisch T. Acute otitis media, part 1: standardizing otoscope assess-

Galveston, TX 77555-0344 ment of the tympanic membrane. J Investig Med. 2002;50:144A

22. McCormick DP, Friedman N, Saeed K, Chonmaitree T, Baldwin CD,

Klimisch T. Acute otitis media, part 2: relation between appearance of

Norman Friedman, MD the tympanic membrane and parent perception of illness. J Investig Med.

Department of Otolaryngology 2002;50:144A

Children’s Hospital 23. Block SL. Acute otitis media: bunnies, disposables, and bacterial origi-

Denver, CO 80218 nal sin! Pediatrics. 2003;111:217–218

24. Bluestone CD, Gates GA, Klein JO, Mogi G, Ogra PL, Paparella MM,

Paradise JL, Tos M. Definitions, terminology, and classification of otitis

Davis C. Teichgraeber, BA media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:9

University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston 25. Finitzo T, Friel-Patti S, Chinn K, Brown O. Tympanometry and otoscopy

Galveston, TX 77555-1119 prior to myringotomy: issues in diagnosis of otitis media. Int J Pediatr

Otolaryngol. 1992;24:103

26. Le CT, Daly KA, Margolis RH, Lindgren BR, Giebink GS. A clinical

Tasnee Chonmaitree, MD profile of otitis media. Arch Otolaryntol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:

Division of Infectious Diseases 1225–1228

University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston 27. Siegel S. Nonparametric Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. New York,

Galveston, TX 77555-0371 NY: McGraw-Hill; 1956

28. Howie VM, Ploussard JH, Lester RL Jr. Otitis media: a clinical and

bacterial correlation. Pediatrics. 1970;45:29 –35

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 29. Rodriguez WJ, Schwartz RH. Streptococcus pneumoniae causes otitis

media with higher fever and more redness of tympanic membranes

This work was supported by grant M01 RR 00073 from the

than Haemophilus influenzae or Moraxella catarrhalis. Pediatr Infect Dis J.

National Center for Research Resources and grant R01 HS10613-02

1999;18:942–949

from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Eiizabeth

30. Heikkinen T, Ghaffar F, Okorodudu AO, Chonmaitree T. Serum inter-

Diaz, PA, assisted with data collection, and Mary H. Whitby

leukin-6 in bacterial and non-bacterial acute otitis media. Pediatrics.

assisted in preparation of the manuscript.

1998;102:296 –299

31. Takata GS, Chan LS, Shekelle P, Morton SC, Mason W, Marcy SM.

REFERENCES Evidence assessment of management of acute otitis media: I. The role of

1. Coffey JD Jr. Otitis media in the practice of pediatrics: bacteriological antibiotics in treatment of uncomplicated acute otitis media. Pediatrics.

and clinical observations. Pediatrics. 1966;38:25–32 2001;108:239 –247

2. Halsted C, Lepow ML, Balassanian N, Emmerich J, Wolinsky E. Otitis 32. Kaleida PH, Casselbrant ML, Rockette HE, et al. Amoxicillin or myrin-

media: clinical observations, microbiology, and evaluation of therapy. gotomy or both for acute otitis media: results of a randomized clinical

Am J Dis Child. 1968;115:542–551 trial. Pediatrics. 1991;87:466 – 474

3. Karelitz S. Myringitis bullosa haemorrhagica. Am J Dis Child. 1937;53: 33. Dowell F, Marcy SM, Phillips WR, Gerber MA, Schwartz B. Principles of

510 –516 judicious use of antimicrobial agents for pediatric upper respiratory

4. Knappett EA. Myringitis bullosa. Br Med J. 1976;1:1402–1403 infections. Pediatrics. 1998;101(suppl):163–165

5. Woo JKS, van Hasselt CA, Gluckman PGC. Myringitis bullosa

haemorrhagica: clinical course influenced by tympanosclerosis. J Laryn-

gol Otol. 1992;106:162–163

6. Marais J, Dale BAB. Bullous myringitis: a review. Clin Otolaryngol.

1997;22:497– 499

7. Rifkind D, Chanock R, Kravetz H, Johnson K, Knight V. Ear involve-

ment (myringitis) and primary atypical pneumonia following inocula- Longstanding Obliterative

tion of volunteers with Eaton agent. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1962;85:479 – 489

8. Couch RB, Cate TR, Chanock RM. Infection with artificially propagated

Panarteritis in Kawasaki Disease:

Eaton agent. JAMA. 1964;187:442– 447

9. Sobeslavsky O, Syrucek L, Bruckova M, Abrahamovic M. The etiolog-

Lack of Cyclosporin A Effect

ical role of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in otitis media in children. Pediatrics.

1965;35:652– 657 ABSTRACT. Kawasaki disease is a childhood vasculi-

10. Clyde WA Jr, Denny FW. Mycoplasma infections in childhood. Pediat- tis of medium-sized vessels, affecting the coronary arter-

rics. 1967;40:669 – 684 ies in particular. We have treated a therapy-resistant

11. Merrifield DO, Miller GS. The etiology and clinical course of bullous child who met all diagnostic criteria for Kawasaki dis-

myringitis. Arch Otolaryngol. 1966;84:487– 489 ease. After the boy was given intravenous immunoglobu-

12. Roberts DB. The etiology of bullous myringitis and the role of myco-

plasmas in ear disease: a review. Pediatrics. 1980;65:761–766

13. Hahn HB Jr, Riggs MW, Hutchinson LR. Myringitis bullosa. Clin Pediatr. Received for publication Feb 20, 2003; accepted Jun 6, 2003.

1998;37:265–267 Address correspondence to Taco W. Kuijpers, MD, PhD, Emma Children’s

14. Palmu AAI, Kotikoski MJ, Kaijalainen TH, Puhakka HJ. Bacterial etiol- Hospital, Academic Medical Center (G8 –205), Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ

ogy of acute myringitis in children less than two years of age. Pediatr Amsterdam, the Netherlands. E-mail: t.w.kuijpers@amc.uva.nl

Infect Dis J. 2001;20:607– 611 PEDIATRICS (ISSN 0031 4005). Copyright © 2003 by the American Acad-

15. Rosenblut A, Santolaya ME, Gonzalez P, et al. Bacterial and viral emy of Pediatrics.

986 EXPERIENCE AND REASON

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on November 3, 2019

Bullous Myringitis: A Case-Control Study

David P. McCormick, Kokab A. Saeed, Carmen Pittman, Constance D. Baldwin,

Norman Friedman, Davis C. Teichgraeber and Tasnee Chonmaitree

Pediatrics 2003;112;982

DOI: 10.1542/peds.112.4.982

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/112/4/982

References This article cites 31 articles, 9 of which you can access for free at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/112/4/982#BIBL

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Infectious Disease

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/infectious_diseases_su

b

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on November 3, 2019

Bullous Myringitis: A Case-Control Study

David P. McCormick, Kokab A. Saeed, Carmen Pittman, Constance D. Baldwin,

Norman Friedman, Davis C. Teichgraeber and Tasnee Chonmaitree

Pediatrics 2003;112;982

DOI: 10.1542/peds.112.4.982

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/112/4/982

Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois,

60007. Copyright © 2003 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN:

1073-0397.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on November 3, 2019

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5814)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Invocation of LilithDocument4 pagesInvocation of Liliths.bheeshmar100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Pestel Grameen BankDocument11 pagesPestel Grameen BankS.M.HILAL50% (2)

- Review Journal Articles FinalDocument6 pagesReview Journal Articles FinalLeo PilayanNo ratings yet

- 5 OSH Management SystemDocument33 pages5 OSH Management SystemzamidiNo ratings yet

- Galendez - Final Requirements in Pauline EthicsDocument25 pagesGalendez - Final Requirements in Pauline EthicsCris Galendez100% (2)

- 3 Chronic MyringitisDocument19 pages3 Chronic MyringitissyahputriNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument7 pagesResearch ArticlesyahputriNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument5 pagesCase ReportsyahputriNo ratings yet

- Did You Know?: Stroke Occurs in Toddlers, Children, and TeensDocument1 pageDid You Know?: Stroke Occurs in Toddlers, Children, and TeenssyahputriNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Status Kesehatan Neonatal Dengan Kematian Bayi: Dwi Setyo Rini Dan Nunik PuspitasariDocument8 pagesHubungan Status Kesehatan Neonatal Dengan Kematian Bayi: Dwi Setyo Rini Dan Nunik PuspitasarisyahputriNo ratings yet

- Serum Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein Levels As Markers of Bacterial Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesSerum Procalcitonin and C-Reactive Protein Levels As Markers of Bacterial Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysissyahputriNo ratings yet

- KPD AsfikDocument13 pagesKPD AsfiksyahputriNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Mass SpectrometryDocument3 pagesComparison of Mass SpectrometryMohammed Kahla'aNo ratings yet

- Business Class M2 Maintenance ManualDocument153 pagesBusiness Class M2 Maintenance ManualEdwin Alfonso Hernandez Montes100% (2)

- Esquema EquipoDocument152 pagesEsquema EquipoHernan SamNo ratings yet

- Employee Retention Strategies HDFCDocument83 pagesEmployee Retention Strategies HDFCsuryakantshrotriya100% (2)

- S1062359022700030 PDFDocument7 pagesS1062359022700030 PDFVengateshwaran TDNo ratings yet

- Color by Number: Biomolecules Edition: Name: - PeriodDocument5 pagesColor by Number: Biomolecules Edition: Name: - PeriodCecilia Enriquez-MenesesNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Midterm Practice TestDocument24 pagesChemistry Midterm Practice TestClara BetancourNo ratings yet

- PDF Introduction To General Organic and Biochemistry 12Th Edition Frederick Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Introduction To General Organic and Biochemistry 12Th Edition Frederick Ebook Full Chapterlynne.finney723100% (3)

- Pharmarack - IPM Diaries - Strategic Partnerships - May 2024Document42 pagesPharmarack - IPM Diaries - Strategic Partnerships - May 2024Shafi UllahNo ratings yet

- Region 4A FruitsDocument23 pagesRegion 4A FruitsAdrian Paul Liveta100% (2)

- Use of Biotrickling Filter Technology To Solve Odour and Safety Concerns at Dubai Sports City Sewage Treatment PlantDocument25 pagesUse of Biotrickling Filter Technology To Solve Odour and Safety Concerns at Dubai Sports City Sewage Treatment PlantChau MinhNo ratings yet

- 1 Mechanical Behavior of MaterialsDocument7 pages1 Mechanical Behavior of MaterialsMohammed Rashik B CNo ratings yet

- Fault Indicator-TonyDocument53 pagesFault Indicator-TonyCesarNo ratings yet

- Retirees Health Monitoring OCTOBERDocument3 pagesRetirees Health Monitoring OCTOBERBfp Caraga SisonfstnNo ratings yet

- Permeability: Tri-Flex 2 Five-Cell Permeability Test System Tri-Flex 2 Three-Cell Permeability Test SystemDocument7 pagesPermeability: Tri-Flex 2 Five-Cell Permeability Test System Tri-Flex 2 Three-Cell Permeability Test SystemJorge SanchezNo ratings yet

- Rapid Lateral Flow Test StripsDocument36 pagesRapid Lateral Flow Test StripsKevin LunaNo ratings yet

- Community Based Disaster Management Training For Nursing StudentsDocument14 pagesCommunity Based Disaster Management Training For Nursing StudentsNeli HusniawatiNo ratings yet

- EARTH SCIENCE Week 1 ActivitiesDocument3 pagesEARTH SCIENCE Week 1 ActivitiesKristian AaronNo ratings yet

- Startups: The Future OF IndiaDocument18 pagesStartups: The Future OF IndiaVedanta AswarNo ratings yet

- Toshiba Aplio XGDocument6 pagesToshiba Aplio XGMed CWTNo ratings yet

- HTML ExamplesDocument80 pagesHTML ExamplesZaraNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Conditional Probability and Bayes Theorem For Data Science ProfessionalsDocument12 pagesIntroduction To Conditional Probability and Bayes Theorem For Data Science ProfessionalsNicholas Pindar DibalNo ratings yet

- Electronics ProjectsDocument4 pagesElectronics ProjectsMoses MberwaNo ratings yet

- Catalog BB Type HDocument2 pagesCatalog BB Type HdioalfanandaNo ratings yet

- Features: Switching RegulatorDocument6 pagesFeatures: Switching RegulatorMai Thanh SơnNo ratings yet