Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2016 10 27 Sports Babu PDF

2016 10 27 Sports Babu PDF

Uploaded by

refniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2016 10 27 Sports Babu PDF

2016 10 27 Sports Babu PDF

Uploaded by

refniCopyright:

Available Formats

SP ORTS ME DICIN E

Diagnosis and Management of Meniscal Injury

JACOB BABU, MD, MHA; ROBERT M. SHALVOY, MD; STEVE B. BEHRENS, MD

A BST RA C T P RESENTATION

Meniscal injury is a common cause for presentation to Knee pain can be the result of numerous possible intra- and

the emergency department or primary care physician’s extra-articular diagnoses, all of which must be kept in the

office. Meniscal injuries can be the result of a forceful, differential when evaluating a patient. Meniscal tears can

twisting event in a young athlete’s knee or it can insid- be identified by asking a few focused questions during the

iously present in the older patient. Many patients with patient evaluation. The mechanism of injury is important as

meniscal pathology appropriately undergo conservative are the presence of specific symptoms after injury.

management with a primary care physician while some Acute meniscal tears are most often associated with a

may need referral to an orthopedist for operative inter- twisting mechanism to the knee while the foot is planted,

vention. Arthroscopic surgery to address the menisci is providing an axial load. The joint swelling with a meniscus

the most frequently performed procedure on the knee tear is more likely to present in a delayed fashion (> 24 hours).

and one of the most regularly performed surgeries in or- Atraumatic, degenerative meniscal pathology more fre-

thopedic surgery.1 The purpose of this paper is to help quently presents with an insidious onset of pain. This diag-

elucidate the diagnosis and management of meniscal nosis can be difficult to distinguish from osteoarthritis in

pathology resulting in knee pain. the older patient. Mechanical symptoms are relatively com-

K E YWORD S: meniscal injury, knee pain, osteoarthritis, mon, with patients often describing the sensation of ‘lock-

arthroscopy, orthopedic referral ing,’ ‘clicking,’ ‘popping,’ and sometimes even a feeling of

‘giving way’ of the knee. Symptoms tend to wax and wane

with activity levels.

On physical examination, joint line tenderness is often

INTRO D U C T I O N described as the most sensitive finding for diagnosing a

The frequency in which meniscal tears occur makes it an meniscal tear; however, it is not very specific.7 Blocks to

important injury to identify by the medical practitioner. active and passive range of motion, especially to deep flex-

Acute, traumatic tears in the young patient and atraumatic, ion, are associated with more complex meniscal tears. A

degenerative tears in the older patient represent a contin- few provocative examination maneuvers for meniscal pain

uum of pathology, often presenting with their own diffi- include the Apley Compression, McMurray, Steinman and

culties in diagnosis and management. The prevalence of Thessaly tests, demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2.7,8 The basic

meniscal tears in the general population has been challeng- premise of these tests involves applying an axial force through

ing to identify due to the high frequency of asymptomatic or the knee joint to simulate weight-bearing while providing

undiagnosed lesions. In some Northern European countries, a rotational moment about the leg to try to elicit clicking,

the estimated incidence of meniscal tears is 2 per 1000 per- popping or pain. Kocabey et al. evaluated the effectiveness

son-years.2 A study by Englund et al., focusing on degenera- of various physical examination maneuvers in diagnosing

tive tears, found that 35% of enrolled patients older than 50 meniscal pathology and found the combination of joint

years old had imaging evidence of a meniscal tear, with ⅔ line tenderness, positive McMurray, Steinmann and Apley

of these being asymptomatic.3 Risk factors associated with tests to have an 80% sensitivity for medial meniscal pathol-

the development of a symptomatic meniscal tear have been ogy and a 92% sensitivity for lateral meniscal pathology.8

identified to be a BMI > 25 kg/m², male sex, and occupa-

tions requiring kneeling, squatting or stair-climbing.2-4 A

military study looking at more acute, traumatic meniscal A NATOMY

tears estimated the incidence in active duty personnel to be The menisci are fibrocartilaginous structures which impor-

8.27 per 1000 person-years.5 In this study, age was found to tantly serve as load-sharing components of the knee joint.

be a variable associated with elevated rates of injury, with By increasing the surface area of contact between the femur

tears occurring 4 times as often in those over 40 compared to and tibia, they can significantly decrease contact stresses

those less than 20 years of age.5 Arthroscopic meniscectomy experienced by articular cartilage. Menisci also function

is estimated to occur 400,000-700,000 times annually.1,6 as secondary restraints to anterior/posterior translation of

W W W. R I M E D . O R G | RIMJ ARCHIVES | O C T O B E R W E B PA G E OCTOBER 2016 RHODE ISLAND MEDICAL JOURNAL 27

SP ORTS ME DICIN E

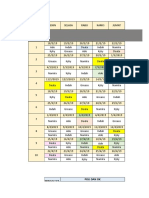

Figure 1. The Thessaly test consists of internal and external rotation of the Figure 2. The McMurray Test is performed with the patient in the supine

body with the knee flexed at 5 and 20 degrees. The examiner can offer position. The examiner places one hand on the heel, which will provide

assistance by holding the patient’s hands for stabilization. Reproduction internal and external rotation moments on the tibia. The other hand is free

of symptoms/pain is a positive finding. to palpate the medial/lateral knee joint line and serve as a lever for val-

gus/varus forces. Reproduction of pain or ‘clicking’ is considered positive.

the tibia with the primary restraint being provided by the test available, albeit with a high false positive rate. MRI is

cruciate ligaments. The menisci are triangular in cross-sec- often not necessary when osteoarthritis is recognized on

tion, and predominantly comprised of water, proteoglycans plain films or there is a high clinical suspicion for menis-

and Type 1 collagen.6 The medial meniscus is c-shaped with cal pathology. On MRI, a linear hyperintensity that extends

multiple capsular attachments including the medial collat- to the superior or inferior joint surface is diagnostic of a

eral ligament, making it much less mobile than the lateral meniscal tear, most sensitively identified on T1 sagittal and

meniscus which is more circular and devoid of ligamen- coronal slices.10 Parameniscal cysts visualized on MRI are

tous constraint. This disparity in motion contributes to the most often seen in the presence of meniscal tears, so images

frequency in which each meniscus is injured. The medial must be carefully scrutinized when cysts are present. A

meniscus is injured much more often than the lateral menis- study performed by Zanetti et al. utilized MRI to evaluate

cus, with the posterior horn being the most afflicted com- 100 patients that had unilateral symptoms consistent with

ponent. The lateral meniscus is more commonly injured a meniscal tear.11 MRIs were performed on the symptom-

in association with ACL tears. In ACL-deficient knees, the atic and asymptomatic contralateral knee. Meniscal tears

menisci become increasingly important restraints to anterior were found in 57 of the symptomatic knees and 36 of the

translation of the tibia, predisposing it to injury. The medial asymptomatic knees. 11 Symptoms correlated most with

and lateral inferior genicular arteries provide blood supply radial, vertical and complex, displaced types of meniscal

to the peripheral ¼ to ⅓ of the menisci, with the remaining tears.11 Another study showed that MRI had a sensitivity of

central portion of the meniscus receiving its nutrition via 91.4 percent and specificity of 81.1 percent for identifying

diffusion from the synovial fluid.6 The poor vascularity of medial meniscus tears and a sensitivity and specificity of 76

the central meniscus accounts for its very limited inherent and 93.3 percent, respectively, for identifying lateral-sided

capacity to heal. The menisci have been found to have noci- tears.12 The management of meniscal tears is centered on

ceptor/mechanoreceptor innervation at the peripheral ⅔ and the presence of symptoms; this study recognizes that a large

at the anterior and posterior horns from histologic study.9 percentage of meniscal tears are asymptomatic.

IMA GI N G TEA R C ONF IGU RATION

Plain radiographs of the knee provide little information Vertical or longitudinal tears in the sagittal plane, as seen

about meniscal pathology. However, they are still valuable in Figure 3, are the most common type of meniscal tear

initial tests and provide information about bony anatomy and can be repaired when present in the peripheral third

and alignment. MRI is the most sensitive diagnostic imaging of the meniscus.6 Radial tears are tears that initiate in the

W W W. R I M E D . O R G | RIMJ ARCHIVES | O C T O B E R W E B PA G E OCTOBER 2016 RHODE ISLAND MEDICAL JOURNAL 28

SP ORTS ME DICIN E

central portion of the meniscus and propagate to the Figure 3. Meniscal tear patterns

periphery; they are usually not repairable due to the Image Courtesy of Michaela Procaccini

poor vascularity of this area of the meniscus. When

these tears are symptomatic, a partial meniscec-

tomy is indicated. Bucket-handle tears are vertical

tears with displacement that can cause mechanical

blocks to flexion/extension. Flap and parrot-beak

tears are tears that initiate centrally and continue in

a circumferential manner.6

M A N A GE M EN T

Meniscal tears require treatment when pain is

unmanageable or function is impaired. Some menis-

cal tears are managed successfully without opera-

tive intervention. This is typically consistent with

small radial tears and stable, nondisplaced longi-

tudinal tears. ACL-deficient knees with no plan

for ACL reconstruction and degenerative tears in

patients with osteoarthritis are usually not candi-

dates for arthroscopic treatment.6 Several studies

have shown good results from managing certain

meniscal tears conservatively with a protocol of

ice, NSAIDs, and physical therapy.13-16 Physical

therapy for these injuries focuses on strengthening

the muscles of the injured extremity, especially

surrounding the knee, as well as maintaining range

of motion of the knee and hip.17-18 Supervised ther-

apy sessions emphasizing exercises such as quadri-

ceps sets, hamstring curls, straight-leg raises, and

heel raises have been shown to produce statisti-

cally significant improvements in knee pain and

functional outcome scores.17-18 Patients should be

encouraged to avoid deep-knee flexion activities

that exacerbate their pain such as squatting and

kneeling.17-18 Intra-articular steroid injections can

be useful adjuncts to minimize inflammation and

suppress symptoms in patients with osteoarthritis.

Several studies have shown statistically significant,

short-term improvement in pain following an intra-articular surgery for patients with symptoms consistent with a degen-

steroid injection lasting 2–4 weeks or longer.13 erative medial meniscus tear without osteoarthritis.16 There

Katz et al. performed a randomized controlled trial comparing were no significant differences in change from baseline to 12

arthroscopic meniscectomy to a standardized physical therapy months in any of the primary outcome scores, regardless of

regimen in 351 patients 45 years and older with MRI-confirmed intervention.16 The effect of various biases, crossover from

meniscal tear and osteoarthritis.14 This study showed no signif- treatment groups, and the external validity of these trials

icant differences in magnitude of improvement in functional have recently brought some of these data into question.19

status evaluated by Western Ontario and McMaster Arthritis These studies demonstrate the difficulty practitioners have

Index (WOMAC) as well as pain at 6 and 12 months after inter- deciphering whether knee pain is the result of osteoarthritis

vention.14 Moseley et al. compared outcomes after randomiza- or a symptomatic meniscal injury, and subsequently deter-

tion of 180 patients with osteoarthritis and meniscal tears to mining the appropriate management. However, they do

an arthroscopic debridement, arthroscopic lavage, or placebo reinforce the importance of attempting conservative man-

surgery group and reported no significant differences in the agement, especially for the older patient with a degenerative

Knee-Specific Pain Scale at one- and two-year follow-up.15 Sih- tear. Some clues that can help identify the source of pain are

vonen et al. evaluated outcomes after random assignment to the mechanism of injury, radiographic findings consistent

either arthroscopic partial-meniscectomy or a sham-controlled with osteoarthritis, and patient demographics.

W W W. R I M E D . O R G | RIMJ ARCHIVES | O C T O B E R W E B PA G E OCTOBER 2016 RHODE ISLAND MEDICAL JOURNAL 29

SP ORTS ME DICIN E

Patients with large or complex tears, a traumatic mecha- 7. Fowler PJ, Lubliner JA. The predictive value of five clinical

nism, or a large joint effusion are likely candidates for oper- signs in the evaluation of meniscal pathology. Arthroscopy,

1989;5:184-6.

ative intervention. Severe pain with provocative maneuvers 8. Kocabey Y, Tetik O, Isbell W, Atay O, Johnson D. (2004). The

such as the McMurray, Apley, and Steinman tests or any value of clinical examination versus magnetic resonance imag-

patient with a locked knee are also likely surgical candi- ing in the diagnosis of meniscal tears and anterior cruciate liga-

ment rupture. Arthroscopy, 20(7), 696-700

dates.6, 20 Patients with persistent symptoms after a period of

9. McMurray T. The semilunar cartilages. Br J Surg, 1942;29:407-14.

conservative management should receive orthopedic consul-

10. Sanders T, Miller M. (2005). A Systematic Approach to Magnetic

tation for either arthroscopy or arthroplasty as appropriate.6, Resonance Imaging Interpretation of Sports Medicine Injuries of

20

Operative options include partial meniscectomy, total the Knee. Am J Sports Med, 33(1), 131-148.

meniscectomy, meniscal repair, and meniscal transplanta- 11. Zanetti M, Pfirrmann C, Schmid M, Romero J, Seifert B, Hodler

J. (2003). Patients with suspected meniscal tears: Prevalence of

tion. A partial meniscectomy is by far the most common abnormalities seen on MRI of 100 symptomatic and 100 con-

procedure preferred for centrally located radial tears, com- tralateral asymptomatic knees. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 181(3),

plex tears away from the periphery, and degenerative tears.20 635-641

Peripheral tears that have good vascularity and subse- 12. Crawford R, Walley G, Bridgman S, Maffulli N. (2007). Magnetic

resonance imaging versus arthroscopy in the diagnosis of knee

quently a greater likelihood of healing are often better pathology, concentrating on meniscal lesions and ACL tears: A

targeted by meniscal repair procedures. 6, 20 This includes systematic review. British Medical Bulletin.

longitudinal tears located peripherally, especially in young 13. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Robinson V, Gee T, Bourne R, Wells

patients, and tears associated with ACL injury when repaired G. (2006). Intraarticular corticosteroid for treatment of osteoar-

thritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, (2), CD005328

concomitantly.20 14. Katz J, Brophy R, Chaisson C, Chaves L, Cole B, Dahm D, Don-

Total meniscectomies are rarely performed considering nell-Fink L, et al. (2013). Surgery versus physical therapy for a

the implication of increased stresses experienced by artic- meniscal tear and osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med, 368(18), 1675-84.

ular cartilage as well as early degenerative changes.6 Menis- 15. Moseley J, OʼMalley K, Petersen N, Menke T, Brody B, Kuyken-

dall D, Hollingsworth J, et al. (2002). A Controlled Trial of Ar-

cal transplantation is usually considered after partial or throscopic Surgery for Osteoarthritis of the Knee. N Engl J Med,

total meniscectomy with persistent symptoms in younger 347(2):81-8

patients that have reached skeletal maturity without 16. Sihvonen R, Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Itälä A, Joukainen A,

arthritic changes of the knee. Nurmi H, Kalske J, et al. (2013). Arthroscopic partial meniscec-

tomy versus sham surgery for a degenerative meniscal tear. N

Engl J Med, 369(26), 2515-24.

17. Stensrud S. (2012). A 12-Week Exercise Therapy Program in Mid-

CON C L U S I O N dle-Aged Patients With Degenerative Meniscus Tears: A Case

Series With 1 Year Follow Up. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 42(11),

Meniscal injury is one of the more common musculoskeletal 919-931.

conditions and a frequent cause of knee pain. It is important 18. Yim J, Seon J, Song E, Choi J, Kim M, Lee K, Seo H. (2013). A

for physicians to recognize meniscal pathology as a source of comparative study of meniscectomy and nonoperative treat-

knee pain and not solely an MRI finding. Painful tears can be ment for degenerative horizontal tears of the medial menis-

cus. Am J Sports Medicine, 41:1565–1570.

managed conservatively in certain circumstances as well as

19. Ha A, Shalvoy R, Voisinet A, Racine J, Aaron R. (2016). Con-

surgically with success. troversial Role of Arthroscopic Meniscectomy of the Knee: A

Review. WJO, 7(5):287-92.

20. Mordecai S, Al-Hadithy N, Ware H, Gupte C. (2014). Treatment

References of meniscal tears: An evidence based approach. WJO, 5(3), 233-41.

1. Kim S, Bosque J, Meehan J. P, Jamali A, Marder R. (2011). In-

crease in outpatient knee arthroscopy in the United States: a Authors

comparison of National Surveys of Ambulatory Surgery, 1996 Jacob Babu, MD, MHA, Resident, Department of Orthopaedics,

and 2006. The JBJS. American volume, 93(11), 994-1000. Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI.

2. Bhattacharyya T, Gale D, Dewire P, Totterman S, Gale M. E, Mc- Robert M. Shalvoy, MD, Executive Chief of Orthopedic Surgery &

Laughlin S, Einhorn T, et al. (2003). The clinical importance of

Sports Medicine, Care New England Health System, Assistant

meniscal tears demonstrated by magnetic resonance imaging in

osteoarthritis of the knee. The JBJS. American volume, 85-A, 4-9. Professor of Orthopedic Surgery, Alpert Medical School of

Brown University, Providence, RI.

3. Englund M, Guermazi A, Gale D, Hunter D.J, Aliabadi P, Clan-

cy M, Felson D. (2008). Incidental meniscal findings on knee Steve B. Behrens, MD, Attending Orthopedic Surgeon, Care New

MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med, 359(11), England Health System, Providence, RI.

1108-1115.

4. Snoeker B, Bakker E, Kegel C, Lucas C. (2013). Risk factors for Correspondence

meniscal tears: a systematic review including meta-analysis. J Jacob Babu, MD

Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 43(6), 352-67. Department of Orthopaedics

5. Jones J.C, Burks R, Owens B, Sturdivant R, Svoboda S, Cameron Rhode Island Hospital

K. (2012). Incidence and risk factors associated with meniscal

593 Eddy Street

injuries among active-duty US Military service members. J Athl

Train, 47(1), 67-73. Providence, RI 02903

6. Boyer M. (2014). AAOS Comprehensive Orthopedic Review. 401-444-4030

Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons, 2, jacob_babu@brown.edu

1397-1402.

W W W. R I M E D . O R G | RIMJ ARCHIVES | O C T O B E R W E B PA G E OCTOBER 2016 RHODE ISLAND MEDICAL JOURNAL 30

You might also like

- Clinical Worksheet Kenneth Bronson Jasgou1752Document2 pagesClinical Worksheet Kenneth Bronson Jasgou1752Jasmyn Rose100% (1)

- MeniscalDocument6 pagesMeniscalسيف فلاح حسنNo ratings yet

- Meniscal Tear: Presentation, Diagnosis and Management: Australian Family Physician April 2012Document6 pagesMeniscal Tear: Presentation, Diagnosis and Management: Australian Family Physician April 2012raditya kusumaNo ratings yet

- Meniscal Tears and Discoid Meniscus in Children .4Document10 pagesMeniscal Tears and Discoid Meniscus in Children .4cooperorthopaedicsNo ratings yet

- Cavanaugh, J. (2014) - Rehabilitation of Meniscal Injury and Surgery. Journal of Knee SurgeryDocument20 pagesCavanaugh, J. (2014) - Rehabilitation of Meniscal Injury and Surgery. Journal of Knee SurgeryDanijela HalilovićNo ratings yet

- Meniscal Tears in Young Athletes Should Undergo Repair If PossibleDocument8 pagesMeniscal Tears in Young Athletes Should Undergo Repair If PossibleVanjaGocovVukicevicNo ratings yet

- Menisco Current ConceptDocument7 pagesMenisco Current ConceptJulio Cesar Guillen MoralesNo ratings yet

- Degenerative Meniscus - Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options - PMCDocument10 pagesDegenerative Meniscus - Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment Options - PMCAhmedNo ratings yet

- The Meniscus in Kne e Osteoarthritis: Martin Englund,, Ali Guermazi,, L. Stefan LohmanderDocument12 pagesThe Meniscus in Kne e Osteoarthritis: Martin Englund,, Ali Guermazi,, L. Stefan LohmanderNati GallardoNo ratings yet

- (SPORT) Meniscal TearsDocument51 pages(SPORT) Meniscal TearsPuteriNurAdeebaNasaeeNo ratings yet

- 18 Management of Traumatic Meniscal Tear andDocument27 pages18 Management of Traumatic Meniscal Tear anddados2000No ratings yet

- Knee - Meniscal TearsDocument8 pagesKnee - Meniscal TearsEmEr KSlNo ratings yet

- The Meniscus Tear. State of The Art of Rehabilitation Protocols Related To Surgical ProceduresDocument7 pagesThe Meniscus Tear. State of The Art of Rehabilitation Protocols Related To Surgical ProceduresLeandro LimaNo ratings yet

- Meniscal CystsDocument5 pagesMeniscal CystsgayutNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument3 pagesCase Reportandrul556723No ratings yet

- Differential Diagnosis of Finger DropDocument4 pagesDifferential Diagnosis of Finger DropR HariNo ratings yet

- Sonography of The Knee Joint PDFDocument8 pagesSonography of The Knee Joint PDFChavdarNo ratings yet

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of The Knee: Identification of Difficult-To-Diagnose Meniscal LesionsDocument10 pagesMagnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of The Knee: Identification of Difficult-To-Diagnose Meniscal LesionsDanaAmaranducaiNo ratings yet

- Conferences and Reviews: Cervical SpondylosisDocument9 pagesConferences and Reviews: Cervical SpondylosisPrasanna GallaNo ratings yet

- Save The MeniscusDocument8 pagesSave The MeniscusRocio CabreraNo ratings yet

- The Meniscus Is A Fibercartilagenous Structure, Which Plays A Significant Role in MaintainingDocument7 pagesThe Meniscus Is A Fibercartilagenous Structure, Which Plays A Significant Role in MaintainingStefan StefNo ratings yet

- Bilateral Peroneal Tubercle Osteochondroma of The Calcaneus: CaseDocument3 pagesBilateral Peroneal Tubercle Osteochondroma of The Calcaneus: CaseAntony CevallosNo ratings yet

- OAJSM 7753 Meniscal Tears - 042110Document10 pagesOAJSM 7753 Meniscal Tears - 042110Chrysi TsiouriNo ratings yet

- Meniscal InjuriesDocument14 pagesMeniscal InjuriesSara Yasmin TalibNo ratings yet

- Nery 2020Document14 pagesNery 2020viniciusfisio.ortoNo ratings yet

- Meniscal Repair'starke 2009Document12 pagesMeniscal Repair'starke 2009yoel mitreNo ratings yet

- Maus 2012Document29 pagesMaus 2012211097salNo ratings yet

- The KneeDocument73 pagesThe Kneexj74fr4ddxNo ratings yet

- 690 FullDocument8 pages690 Fulldanielalexandersinaga.xiiipa2No ratings yet

- The Role of Arthroscopy in Instability of The Elbow 2023 JSES InternationalDocument6 pagesThe Role of Arthroscopy in Instability of The Elbow 2023 JSES Internationaligor gayosoNo ratings yet

- TFCC InjuriesDocument5 pagesTFCC InjuriesLaineyNo ratings yet

- Ramp Lesions PDFDocument13 pagesRamp Lesions PDFana starcevicNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877056820303662 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S1877056820303662 Mainyoel mitreNo ratings yet

- Matar 2019Document5 pagesMatar 2019QuiroprácticaParaTodosNo ratings yet

- Synovial Knee Disease: MRI Differential Diagnosis: Poster No.: Congress: Type: AuthorsDocument18 pagesSynovial Knee Disease: MRI Differential Diagnosis: Poster No.: Congress: Type: AuthorsEka JuliantaraNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Supracondylar Fractures of The Distal Humerus: Provided by Springer - Publisher ConnectorDocument7 pagesPediatric Supracondylar Fractures of The Distal Humerus: Provided by Springer - Publisher ConnectorBison_sonNo ratings yet

- PIIS2212628721001900Document6 pagesPIIS2212628721001900ANDRES DURANNo ratings yet

- Inside Out Menico RampaDocument6 pagesInside Out Menico RampaNilia AbadNo ratings yet

- Chondral Injuries of The Ankle With Recurrent Lateral Instability: An Arthroscopic StudyDocument8 pagesChondral Injuries of The Ankle With Recurrent Lateral Instability: An Arthroscopic StudyAnonymous kdBDppigENo ratings yet

- Hand Tumors Benign and Malignant Bone Tumors of The HandDocument8 pagesHand Tumors Benign and Malignant Bone Tumors of The HandICNo ratings yet

- Elbow Instability in Children: Lisa L. Lattanza, MD, Greg Keese, MDDocument14 pagesElbow Instability in Children: Lisa L. Lattanza, MD, Greg Keese, MDJoan Ferràs TarragóNo ratings yet

- Laminectomy With Fusion Versus Young LaminoplastyDocument6 pagesLaminectomy With Fusion Versus Young Laminoplasty7w7dzjhgbqNo ratings yet

- Sindrome Do Nervo SupraescapularDocument9 pagesSindrome Do Nervo SupraescapularAna CarolineNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Clinical, MRI, and Arthroscopic Findings: A Guide To Correct Diagnosis of Meniscal TearsDocument4 pagesRelationship Between Clinical, MRI, and Arthroscopic Findings: A Guide To Correct Diagnosis of Meniscal Tearsrais123No ratings yet

- Cervical MyelopathyDocument7 pagesCervical Myelopathybmahmood1No ratings yet

- Bony SkierDocument6 pagesBony SkierChrysi TsiouriNo ratings yet

- Meniscal Repair. Jaoos PDFDocument10 pagesMeniscal Repair. Jaoos PDFkarenNo ratings yet

- Tendon InterventionDocument10 pagesTendon InterventionVerónica Téllez ArriagaNo ratings yet

- Colombian Journal of Anesthesiology: Revista Colombiana de AnestesiologíaDocument4 pagesColombian Journal of Anesthesiology: Revista Colombiana de AnestesiologíaSuci dwi CahyaNo ratings yet

- Lesion de MeniscosDocument18 pagesLesion de MeniscosAmada Angel VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Pinzamiento de Cadea Pincer CamDocument9 pagesPinzamiento de Cadea Pincer Camvlc driveNo ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument15 pagesCase StudyWincy Faith SalazarNo ratings yet

- The Carpal Boss: Review of Diagnosis and Treatment: Min J. Park, MMSC, Surena Namdari, MD, Arnold-Peter Weiss, MDDocument4 pagesThe Carpal Boss: Review of Diagnosis and Treatment: Min J. Park, MMSC, Surena Namdari, MD, Arnold-Peter Weiss, MDStefano Pareschi PasténNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Resection of Symptomatic Osteochondroma of The Distal FemurDocument4 pagesEndoscopic Resection of Symptomatic Osteochondroma of The Distal FemurAlex CirlanNo ratings yet

- Classification of Wrist FracturesDocument6 pagesClassification of Wrist FracturesshinhyejjNo ratings yet

- Ferran Ankle InstabilityDocument8 pagesFerran Ankle Instabilityfahmiatul lailiNo ratings yet

- Realignment Surgery For Malunited Ankle Fracture: Clinical ArticleDocument5 pagesRealignment Surgery For Malunited Ankle Fracture: Clinical ArticleGio VandaNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Multiple Benign Schwannomas of Left Foot A Case ReportDocument7 pagesRecurrent Multiple Benign Schwannomas of Left Foot A Case ReportInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Lateral Tendon Disorders Peroneal Tendinopathy Differential DiagnosisDocument5 pagesLateral Tendon Disorders Peroneal Tendinopathy Differential Diagnosischu_chiang_3No ratings yet

- The MeniscusFrom EverandThe MeniscusPhilippe BeaufilsNo ratings yet

- Surgery of the Cranio-Vertebral JunctionFrom EverandSurgery of the Cranio-Vertebral JunctionEnrico TessitoreNo ratings yet

- Risk of Legionellosis From Exposure To Water AerosDocument9 pagesRisk of Legionellosis From Exposure To Water AerosemilyNo ratings yet

- Mini-Review: Elizabeth Phipps, Devika Prasanna, Wunnie Brima, and Belinda JimDocument12 pagesMini-Review: Elizabeth Phipps, Devika Prasanna, Wunnie Brima, and Belinda JimemilyNo ratings yet

- Mini-Review: Elizabeth Phipps, Devika Prasanna, Wunnie Brima, and Belinda JimDocument9 pagesMini-Review: Elizabeth Phipps, Devika Prasanna, Wunnie Brima, and Belinda JimemilyNo ratings yet

- Mini-Review: Elizabeth Phipps, Devika Prasanna, Wunnie Brima, and Belinda JimDocument10 pagesMini-Review: Elizabeth Phipps, Devika Prasanna, Wunnie Brima, and Belinda JimemilyNo ratings yet

- Minggu Ke-Poli Dan OkDocument18 pagesMinggu Ke-Poli Dan OkemilyNo ratings yet

- Why Would A Person Need A Central Venous Catheter?Document2 pagesWhy Would A Person Need A Central Venous Catheter?emily100% (1)

- Ruñez, Jr. vs. JuradoDocument8 pagesRuñez, Jr. vs. JuradoEric RamilNo ratings yet

- Physical Education: Quarter 2 - Module 2: WEEK 2, Active RecreationDocument47 pagesPhysical Education: Quarter 2 - Module 2: WEEK 2, Active RecreationNiko Igie Albino Pujeda100% (4)

- Celsius StrategicAnalysisDocument27 pagesCelsius StrategicAnalysisbudcrkrNo ratings yet

- JaNus Screening ToolDocument8 pagesJaNus Screening ToolPablo CauichNo ratings yet

- Ask Questions About C.P.RDocument5 pagesAsk Questions About C.P.RAnonymous FCOOcnNo ratings yet

- Cardiac EmergenciesDocument38 pagesCardiac Emergenciesnurasia oktianiNo ratings yet

- BongraftingDocument4 pagesBongraftingjaxine labialNo ratings yet

- Refractive Error 050115Document34 pagesRefractive Error 050115Anonymous l2Fve4PpDNo ratings yet

- Hugh Jackman's Workout - Strong, Lean & PowerfulDocument14 pagesHugh Jackman's Workout - Strong, Lean & PowerfulMouh100% (1)

- Health and Fitness Program Sample ProposalDocument7 pagesHealth and Fitness Program Sample ProposalBusiness PsychologistNo ratings yet

- 3.6.5. One-Shot AcidDocument1 page3.6.5. One-Shot Acidpedro taquichiriNo ratings yet

- International Ayurvedic Medical Journal: A Critical Review On Madatyaya A Critical Review On Madatyaya (Alcoholism)Document7 pagesInternational Ayurvedic Medical Journal: A Critical Review On Madatyaya A Critical Review On Madatyaya (Alcoholism)Abhishek Chakravarthy Abhishek ChakravarthyNo ratings yet

- First Announcement PIR PERDOSSI JOGLOSEMARMAS XXXIIIDocument13 pagesFirst Announcement PIR PERDOSSI JOGLOSEMARMAS XXXIIIRabbi'ahNo ratings yet

- Lighthouse Oct. 28, 2010Document40 pagesLighthouse Oct. 28, 2010VCStarNo ratings yet

- Shelf Prep: Guide To The Internal Medicine ClerkshipDocument2 pagesShelf Prep: Guide To The Internal Medicine ClerkshipRuth SanmooganNo ratings yet

- Quality Control in Occupational Safety and HealthDocument27 pagesQuality Control in Occupational Safety and HealthNecklal SoniNo ratings yet

- 0 - Hospital Design 2020 PDFDocument3 pages0 - Hospital Design 2020 PDFPriya DharshiniNo ratings yet

- RADTECH Room Assignment 0717 CDO PDFDocument5 pagesRADTECH Room Assignment 0717 CDO PDFPhilBoardResultsNo ratings yet

- Chemical Approval ProcessDocument5 pagesChemical Approval ProcessGiovanniNo ratings yet

- Refugees and Asylum DocumentDocument69 pagesRefugees and Asylum DocumentRAKESH KUMAR BAROINo ratings yet

- Sewer Smoke Testing NoticeDocument2 pagesSewer Smoke Testing Noticeapi-442300261No ratings yet

- MBBS Final Prof Annual 2010Document3 pagesMBBS Final Prof Annual 2010MfarhanonlineNo ratings yet

- Clinical Nursing Skills and Techniques 6th Edition Perry Test BankDocument11 pagesClinical Nursing Skills and Techniques 6th Edition Perry Test BankAnnetteOliverrbwcx100% (12)

- Fruit Bat-Aza - Standard - CareDocument60 pagesFruit Bat-Aza - Standard - CareOmar AguilarNo ratings yet

- 2001-003-C-01 Framework For Measuring SuccessDocument21 pages2001-003-C-01 Framework For Measuring SuccessironclawNo ratings yet

- Work Procedure For CCB Concrete Pouring Scheme of Second Floor Columns and Reinforced Concrete Walls and Third Floor SlabDocument28 pagesWork Procedure For CCB Concrete Pouring Scheme of Second Floor Columns and Reinforced Concrete Walls and Third Floor SlabResearcherNo ratings yet

- Functions of Public HealthDocument30 pagesFunctions of Public Healthteklay100% (1)

- SSC CGL Answer Key 16-08-2015 Tier-1 3149329 (Booklet No) Slot Morning SessionDocument7 pagesSSC CGL Answer Key 16-08-2015 Tier-1 3149329 (Booklet No) Slot Morning SessionHimanshu VermaNo ratings yet

- OMS1664 Topic 2 - 1 - 3EssentialSafetyDocument57 pagesOMS1664 Topic 2 - 1 - 3EssentialSafetyGlauco TorresNo ratings yet