Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1

Uploaded by

shabrinaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Uploaded by

shabrinaCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL RESEARCH & CONTRIBUTIONS

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Diagnostic Challenge in a

Nonendemic Setting: Our Experience with 101 Patients

Kevin H Wang, MD; Stephanie A Austin, MD; Sonia H Chen, MD; David C Sonne, MD; Deepak Gurushanthaiah, MD Perm J 2017;21:16-180

E-pub: 06/05/2017 https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-180

ABSTRACT RESULTS

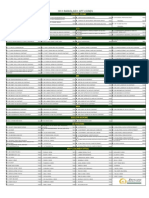

Introduction: We studied the presenting symptoms, time intervals, and workup in- During the study period, 101 patients

volved in the diagnosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in an integrated health care system. met inclusion criteria (demographics are de-

Methods: A retrospective chart review of all patients with a nasopharyngeal carci- scribed in Table 1). Most patients (70, 70%)

noma diagnosis between 2007 and 2010 at Kaiser Permanente Northern California. were of Chinese or Southeast Asian descent,

Main outcome measures included diagnostic time intervals, presenting symptoms, and 70 (70%) were men. The mean age

diagnostic accuracy of nasal endoscopy, imaging, and diagnosis at first otolaryngologist (± standard deviation) was age 52 (±13) years.

(Oto-HNS) visit. Among patients, 64% had late-stage disease

Results: This study included 101 patients: 70 (70%) were of Chinese or of Southeast (stages III/IV) at the time of diagnosis.

Asian descent. The median time intervals along the diagnostic pathway were symptom

onset to primary care physician visit, 6.0 weeks; primary care physician to Oto-HNS, 2.4 Table 1. Patient demographics

weeks; Oto-HNS to pathologic diagnosis, 1.1 weeks; and diagnosis to treatment onset,

Number

5.5 weeks. The most common presenting symptoms were otologic issues (41, 41%), neck Characteristic (N = 101)

mass (39, 39%), nasal issues (32, 32%), and headache/cranial neuropathy (16, 16%). A Mean age, years (SD) 52 (13)

nasopharyngeal lesion was detected in 54 (53%) patients after the first Oto-HNS visit.

Sex

Among the initial nasal endoscopy reports, 32 (32%) did not reveal a nasopharyngeal

Men 70

lesion; 32 (32%) initial imaging studies also did not reveal a nasopharyngeal lesion.

Women 31

There was no correlation between diagnostic delay and disease stage.

Race/ethnicity

Conclusion: Nasopharyngeal carcinoma presenting symptoms are extremely variable,

Chinese/Southeast Asiana 70

and initial misdiagnosis is common. Median time from symptom onset to treatment was

almost six months among patients studied. Nearly one-third of nasopharyngeal cancers Caucasian 22

were missed with nasal endoscopy and imaging. An understanding of the risk factors, Hispanic 6

presenting symptoms, and limitations associated with these diagnostic tests is necessary African American 3

to support earlier detection of this insidious cancer. Histology

WHO I 10

INTRODUCTION the importance of early diagnosis, the WHO II/III 85

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is frequency of delayed diagnoses, and the Unknown 6

rarely diagnosed outside of the endemic ar- relative lack of literature on this topic, we AJCC stage, 7th edition

eas of Southern China and Southeast Asia. sought to examine the pathway to NPC Stage I 6

In the US, NPC incidence is 0.7/100,000 diagnosis in our health care system. Stage II 31

per year.1 As with other cancers, disease Stage III 33

stage heavily influences prognosis, and METHODS Stage IVa 15

efforts directed toward earlier diagnosis The tumor registry at Kaiser Permanente Stage IVb 7

may improve survival. The largest study Northern California was queried for all Stage IVc 9

conducted to date in Hong Kong revealed patients who received an NPC diagnosis T stage

that the mean symptom-to-diagnosis dura- between January 1, 2007, and December

T1 31

tion was 8 months and that earlier presen- 31, 2010. Charts were reviewed for diag-

T2 32

tation correlated with improved 10-year nostic time intervals, symptoms, nasopha-

T3 13

survival.2 To our knowledge, only a single ryngoscopy findings, initial radiographic

T4 25

study from 2001 described NPC in an imaging reports, and initial diagnosis by an

American health care setting.3 August et al otolaryngologist (Oto-HNS). Images were

a

Southeast Asian includes Filipino, Hmong, Laotian,

Pacific Islander, and Vietnamese.

reported a similar average symptom period reviewed with an experienced neuroradi- AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer; SD =

of 7 months before diagnosis.3 Considering ologist in a nonblinded fashion. standard deviation; WHO = World Health Organization.

Kevin H Wang, MD, is a Head and Neck Surgeon at the Oakland Medical Center in CA. E-mail:

kevin.h.wang@kp.org. Stephanie A Austin, MD, is a Head and Neck Surgeon at the Oakland Medical

Center in CA. E-mail: stephaustin@gmail.com. Sonia H Chen, MD, is a Head and Neck Surgeon at the

Oakland Medical Center in CA. E-mail: shchen34@gmail.com. David C Sonne, MD, is a Radiologist at

the Oakland Medical Center in CA. E-mail: chris.d.sonne@kp.org. Deepak Gurushanthaiah, MD, is a

Head and Neck Surgeon at the Oakland Medical Center in CA. E-mail: d.gurushanthaiah@kp.org.

The Permanente Journal/Perm J 2017;21:16-180 1

ORIGINAL RESEARCH & CONTRIBUTIONS

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Diagnostic Challenge in a Nonendemic Setting: Our Experience with 101 Patients

33 patients who had false-negative imag-

Symptom onset PCP Oto-HNS Diagnosis Treatment ing study results.

Of the negative imaging studies, 13

(39%) were identified as suboptimal for

evaluating the nasopharynx for these rea-

sons: 1) fewer than two slices of the naso-

pharynx were captured, 2) lack of contrast,

3) lack of axial-oriented slices, and/or 4)

Total: 23.5 weeks dental artifact. Among the positive scans,

(12.9 - 51.2) only 1 (1.5%) was suboptimal.

Upon review of radiographic images,

Figure 1. Median time intervals in weeks (interquartile ranges). the tumor growth pattern in the nasophar-

Oto-HNS = otolaryngologist; PCP = primary care physician. ynx was exophytic in 53 (52%) patients,

endophytic in 29 (29%), both exophytic

and endophytic in 15 (15%), normal in

The median diagnostic pathway time performed at the first Oto-HNS visit for

1 (1%), and not included in the scan in

intervals are summarized in Figure 1. 84 (83%) patients. Among initial endosco-

3 (3%). Mastoid opacification was found

The longest interval was from symptom pies, 69 (68%) detected a nasopharyngeal

in 53 (52%) images. Sphenoid opacifica-

onset to initial visit with a primary care lesion; the remaining results were docu-

tion was identified in 32 (32%) patients,

physician. The total median interval from mented as normal.

and bony skull base erosion in 30 (30%).

symptom onset to treatment initiation was The first radiographic study was vari-

Ultimately, a nasopharyngeal lesion was

23.5 weeks (interquartile range 12.9-51.2). able; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

first detected with nasal endoscopy in 64

Presenting symptoms, which were ex- was most common (Table 2). Radiologists

(63%) patients, with imaging in 33 (33%),

tremely variable, were categorized into detected nasopharyngeal lesions in 68 of

and intraoperatively for 4 (4%).

4 groups (Figure 2). The most common 101 (67%) patients. When the referring

symptoms were ear-related; neck masses clinician indicated a nasopharyngeal le-

were second most common. Among pa- sion (42, 42% of the time), 39 (93%)

DISCUSSION

In this study, a nasopharyngeal lesion

tients, 33 (33%) experienced symptoms imaging studies confirmed the abnormal-

was diagnosed after the first Oto-HNS

from multiple categories. ity. Among 59 (58%) imaging studies

visit for 54 (53%) patients. No nasopha-

At the first Oto-HNS visit, 54 (53%) with other indications such as sinusitis

ryngeal abnormality was documented for

patients had a nasopharyngeal lesion or neck mass, only 28 (48%) imaging

the remaining patients. Most of these cases

diagnosed (Figure 3). For the remain- reports described a nasopharyngeal lesion.

were initially misdiagnosed and patients

ing patients, other diagnoses were made, All the studies were reviewed again by a

were treated for other conditions such

most commonly middle ear effusion and neuroradiologist in a nonblinded fashion,

as eustachian tube dysfunction, sinusitis,

neck masses. Nasopharyngoscopy was and NPC was identified for 30 (91%) of

or epistaxis without undergoing a cancer

workup. However, the primary diagnosis

was a neck mass for 10 (9%) patients, and

13% cranial (eg, headache, neuropathy)

neck imaging was obtained for 7 patients

within 1 month of the initial visit. Because

appropriate workups were initiated, we did

not consider misdiagnosis as an issue for

these patients. Although clinicians other

35% nasal than Oto-HNS are not expected to diag-

42% ear (eg, obstruction, nose NPC, the high rate of misdiagnosis

(eg, otitis media, epistaxis) by Oto-HNS has not been well described.

hearing loss) In part, this is attributable to the rarity of

NPCs. In our health care system, which

includes more than 3 million patient

members (15% Asian), approximately

130 full-time Oto-HNS each averaged one

NPC diagnosis every 4 years.

NPC is also challenging to diagnose

because of its anatomic isolation. Most of

40% neck mass these cancers remain clinically silent for a

long period of time. Although one-third

Figure 2. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma presenting symptoms. of patients presented with nasal symptoms

2 The Permanente Journal/Perm J 2017;21:16-180

ORIGINAL RESEARCH & CONTRIBUTIONS

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Diagnostic Challenge in a Nonendemic Setting: Our Experience with 101 Patients

trigger an examination of the nasopharynx.

In our study, neck masses were usually

referred appropriately by primary care

physicians and worked-up efficiently by

an Oto-HNS. However, several patients

received misdiagnoses of lipoma, reactive

lymphadenopathy, and neck abscess. Nasal

symptoms such as obstruction, epistaxis,

or sinusitislike symptoms were third most

common upon presentation. These condi-

tions often were initially treated with nasal

steroids, antihistamines, or antibiotics by

a primary care physician before referral to

Figure 3. Initial diagnosis by otolaryngologist. an Oto-HNS. Symptoms such as cranial

neuropathy and headache occurred in 13

such as epistaxis and nasal obstruction, Time Intervals (13%) patients. Cranial neuropathies

most presented only when the cancer be- The median diagnostic pathway time manifested most commonly as diplo-

gan to affect the surrounding organs, caus- intervals in Figure 1 appear to indicate an pia, followed by facial numbness, facial

ing ear symptoms or a neck mass. efficient pathway to diagnosis and treat- droop, and tongue numbness. One-third

Basic demographic data can be used to ment. However, the mean time intervals of patients had symptoms from multiple

assess NPC risk in the context of clinical were much longer: Total time from symp- categories, and 42 different symptom

symptoms. Among our patients with NPC, tom onset to treatment initiation was ten combinations were seen. Such variation

71 (70%) were men, and 83 (82%) were months. The much longer mean time in symptomatology likely contributes to

older than age 40 years. Although other intervals reflect the minority of patients the challenge in diagnosis.

head and neck cancers are rare in people whose care was substantially delayed by

younger than age 40 years, NPC does themselves or by their physicians. One- Nasal Endoscopy

occur in young adults (18 [18%] of our third of patients waited longer than three Nasal endoscopy plays a crucial role

patients were between ages 21 and 39; months before seeking medical attention. in NPC diagnosis. It is performed in the

71 [70%] were of Chinese or Southeast Considering that all of our patients had Oto-HNS office with topical anesthetic in

Asian ethnicity). This ethnic distinction is health insurance, this delay probably re- just a few minutes. For 84 (83%) patients,

important: In our population, there were flects the fact that they were not alarmed endoscopy was performed at the first Oto-

no patients with NPC of Indian, Korean, by symptoms such as hearing loss, neck HNS visit. Findings of the first nasopha-

or Japanese descent. Other epidemiology masses, and nasal obstruction. Additional- ryngoscopy were reported as normal for

studies confirm this ethnic predilection.4 ly, for one-third of patients, the Oto-HNS 32 (32%) patients. Of these patients with

In parts of southern China, NPC is the needed longer than one month to establish an initial negative nasal endoscopy result,

second-most-common cancer among men, the correct diagnosis after the initial visit. 21 (66%) had T1/2 tumors, and 11 (34%)

with an incidence 10 to 20 times that of Even when specialists are equipped with had T3/4 tumors. This false-negative rate

nonendemic populations.5 NPC etiology the proper technology with which to ex- is surprisingly high (especially for T3 and

is thought to involve a combination of amine the nasopharynx, an NPC diagnosis T4 tumors). These examination records

Epstein-Barr virus exposure and genetic can remain elusive. were not available for our review, but we

susceptibility. Those who immigrate to the postulate several explanations. Among tu-

US from endemic areas are at higher risk Presenting Symptoms mors, 29 (29%) were mostly endophytic

for NPC than the general US population, NPC’s presenting symptoms are, in de- on radiographic imaging; therefore, they

but their risk is decreased when compared scending order, ear-related issues, a neck were likely to be submucosal on endo-

with risk for people living in China.5 mass, and nasal and cranial symptoms. scopic exam. Most tumors are thought to

This is in contrast to classic teaching, originate from the fossa of Rosenmüller,

however, which states that a neck mass which is the posterolateral nasopharyngeal

Table 2. Initial radiographic scan type is the most common NPC presenting recess. This space is longer than 1 cm in

(N = 101) symptom.6,7 Ear symptoms occur because depth and less than 5 mm wide in about

MRI 34 the nasopharyngeal tumor compresses or 50% of people.8 It is not always possible

CT neck 33 obstructs the torus tubarius and leads to to visualize the entire fossa, so turning the

CT sinus 19 eustachian tube dysfunction, which can endoscope 90° or approaching the fossa

CT head 7 manifest as a middle ear effusion, acute from the contralateral side may be neces-

Positron emission tomography-CT 8 otitis media, and conductive hearing sary. We hypothesized that many Oto-

CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic loss. In Chinese or Southeast Asian men, HNS do not routinely visualize the fossa’s

resonance imaging. new onset of these ear symptoms should entirety, thereby missing smaller NPCs.

The Permanente Journal/Perm J 2017;21:16-180 3

ORIGINAL RESEARCH & CONTRIBUTIONS

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Diagnostic Challenge in a Nonendemic Setting: Our Experience with 101 Patients

NPC (Figure 4B provides an example of

a false-negative imaging study). The high

false-negative rate underscores the impor-

tance of clinicians communicating clini-

cal context to radiologists when ordering

scans. The challenge remains, however,

that clinicians themselves often do not

suspect NPC and do not communicate

this need to the interpreting radiologist.

Mastoid opacification was found in 53

(52%) patients and sphenoid opacification

in 32 (32%) patients. To our knowledge,

these radiographic findings were not previ-

ously reported as warning signs for NPC.

Figure 4. (A) Example of a T4b nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) with an endoscopic examination that was Although the specificity of these signs is

initially normal. (B) Example of an endophytic NPC initially interpreted as normal on this computed tomogra- unknown, considering that our cohort

phy sinus scan without contrast. The arrow points to a tumor in the right parapharyngeal space. was entirely patients with NPC, we feel

these signs should prompt astute clinicians

The challenge associated with nasopha- undetected on endoscopic exam; a large to closely scrutinize the nasopharynx in

ryngeal assessment was well described by tumor is visualized on MRI. high-risk patients.

Vlantis et al9 in which a 44-point scoring We did not find a correlation between

system was used. This exceptionally thor- Imaging prolonged diagnostic time intervals and

ough evaluation system probably would be A nasopharyngeal lesion was not report- disease stage. This may be explained mainly

more accurate than other evaluations, but ed by the radiologist after viewing 33% by the clinically silent nature of NPC. Even

the time required would pose a challenge of initial scans. During our rereview with with prompt action by both patients and

in daily practice. our neuroradiologist, 91% of these scans the health care system, many patients with

The nasopharyngoscopes used during revealed a nasopharyngeal lesion. Some NPC probably do not develop clinical

this study were standard fiber optic scopes. lesions were subtle and probably detected symptoms until advanced T-stage disease

Video nasopharyngoscopes have improved on the basis of a priori knowledge of the or nodal positivity is present. Nevertheless,

resolution and offer a larger field of view presence of NPC; however, some lesions once these symptoms appear, patients must

and recording/playback capabilities. These were obvious. The first imaging study tech- receive an efficient diagnosis.

newer scopes have recently been adopted nique was highly variable (Table 2), which The limitations of this study include its

widely in our system; with improved visu- reflects the assorted symptom indications small size, its retrospective nature, and the

alization, the incidence of missed NPCs on and diversity among ordering physicians. availability of documentation and examina-

nasal endoscopy should decrease. One-quarter of first scans were ordered by tion data. Patient-reported history is prone

The fact that most (64, 63%) NPCs a non-Oto-HNS. to recall bias, and documentation by physi-

in our study were first detected by nasal Other studies that have examined the di- cians in the medical record was sometimes

endoscopy underscores the importance agnostic accuracy of MRI for NPC found vague. Although we could review each ra-

of performing nasal endoscopy for high- sensitivity to be higher than 90%.10,11 diographic study, review was not performed

risk patients at the initial Oto-HNS visit. However, these studies were performed in in a blinded fashion. Additionally, endo-

High-risk patients include any patient an endemic area on patients “suspected” scopic examinations were unavailable for

from China or Southeast Asia who present to have NPC. In our study, the first imag- review. Finally, the study was conducted at

with an ear complaint, neck mass, nasal ing study was a computed tomography a single institution in a limited geographic

obstruction or cranial symptoms. Con- (CT) scan (neck, sinus, or head), MRI, or area (Northern California).

sidering that nasal endoscopy is relatively a positron emission tomography/CT scan The Institute of Medicine’s recent land-

quick to perform and virtually risk free, in a nonendemic population for which a mark report, Improving Diagnosis in Health

the threshold for its use should be very nasopharyngeal pathology was not sus- Care,13 highlighted the fact that scant data

low for high-risk patients. Additionally, pected 58% of the time. exist on diagnostic error. We hope that our

an understanding of the high false-nega- Although some scans were suboptimal study will provide necessary baseline data

tive rate associated with this examination for examination of the nasopharynx (eg, regarding NPC.

is important when interpreting the find- CT sinus and CT head), we contend

ings. When a high-risk and symptomatic that some of the false-negative scans can CONCLUSION

patient has negative nasal endoscopic probably be explained by inattentional NPC is rarely encountered in our health

exam findings, MRI should be considered blindness.12 For example, when the in- care system and frequently is misdiagnosed.

for further evaluation for NPC. Figure 4A dication was sinusitis, the radiologist Thirty-two percent of nasopharyngeal

provides an example of an NPC that went likely focused on the sinuses and missed cancers are difficult to visualize upon nasal

4 The Permanente Journal/Perm J 2017;21:16-180

ORIGINAL RESEARCH & CONTRIBUTIONS

Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Diagnostic Challenge in a Nonendemic Setting: Our Experience with 101 Patients

endoscopy, and 33% are missed upon an References 8. Loh LE, Chee TS, John AB. The anatomy of the

1. Lee JT, Ko CY. Has survival improved for Fossa of Rosenmuller—its possible influence on

initial imaging study. This descriptive study nasopharyngeal carcinoma in the United States? the detection of occult nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

of misdiagnosis incidence and patterns is a Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005 Feb;132(2):303-8. Singapore Med J 1991 Jun;32(3):154-5.

first step toward understanding the chal- DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.otohns.2004.09.018. 9. Vlantis AC, Bower WF, Woo JK, Tong MC, van

2. Lee AW, Foo W, Law SC, et al. Nasopharyngeal Hasselt CA. Endoscopic assessment of the

lenges associated with NPC diagnosis. Fur- carcinoma: Presenting symptoms and duration before nasopharynx: An objective score of abnormality to

ther work is required to implement changes diagnosis. Hong Kong Med J 1997 Dec;3(4):355-61. predict the likelihood of malignancy. Ann Otol Rhinol

that can reduce diagnostic error. v 3. August M, Dodson TB, Nastri A, Chuang SK. Laryngol 2010 Feb;119(2):77-81. DOI: https://doi.org/

Nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Clinical assessment and 10.1177/000348941011900202.

review of 176 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 10. King AD, Vlantis AC, Tsang RK, et al. Magnetic

Disclosure Statement Oral Radiol Endod 2001 Feb;91(2):205-14. DOI: resonance imaging for the detection of

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to https://doi.org/10.1067/moe.2001.110698. nasopharyngeal carcinoma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol

disclose. 4. Chang ET, Adami HO. The enigmatic epidemiology 2006 Jun-Jul;27(6):1288-91.

of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol 11. King AD, Vlantis AC, Bhatia KS, et al. Primary

Biomarkers Prev 2006 Oct;15(10):1765-77. DOI: nasopharyngeal carcinoma: Diagnostic accuracy

Acknowledgments https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0353. of MR imaging versus that of endoscopy and

Jason E Gilde, MD, created Figure 2. 5. Yu WM, Hussain SS. Incidence of nasopharyngeal endoscopic biopsy. Radiology 2011 Feb;258(2):531-7.

Brenda Moss Feinberg, ELS, provided editorial carcinoma in Chinese immigrants, compared with DOI: https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.10101241.

assistance. Chinese in China and South East Asia: Review. 12. Drew T, Võ ML, Wolfe JM. The invisible gorilla strikes

J Laryngol Otol 2009 Oct;123(10):1067-74. DOI: again: Sustained inattentional blindness in expert

https://doi.org/10.1017/s0022215109005623. observers. Psychol Sci 2013 Sep;24(9):1848-53.

How to Cite this Article 6. Bailey BJ, Johnson JT, Newlands SD, editors. Head DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613479386.

Wang KH, Austin SA, Chen SH, Sonne DC, & neck surgery—otolaryngology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, 13. Balogh EP, Miller BT, Ball JR, editors. Improving

Gurushanthaiah D. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. diagnosis in health care [Internet]. Washington, DC:

diagnostic challenge in a nonendemic setting: Our 7. Tan L, Loh T. Benign and malignant tumors of the National Academies Press; 2015 [cited 2016 Feb 10].

nasopharynx. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, Available from: www.nap.edu/catalog/21794.

experience with 101 patients. Perm J 2017;21:16-180.

et al, editors. Cummings otolaryngology: Head and

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/16-180.

neck surgery. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders;

2015. p 1420-31.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of disease is often easy, often difficult, and often impossible.

— Peter Mere Latham, MD, 1789-1875, British physician

and medical educator, physician extraordinary to Queen Victoria

The Permanente Journal/Perm J 2017;21:16-180 5

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Mastoiditis Jurnal 3Document3 pagesMastoiditis Jurnal 3shabrinaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Jurnal Postgrad MedDocument7 pagesJurnal Postgrad MedBimasenaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Nasal Poly PosisDocument4 pagesNasal Poly PosisDevita RamadaniNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Jurnal Hidung Epistaksis PDFDocument5 pagesJurnal Hidung Epistaksis PDFMaulana ChasanNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Obstetric Factors and Pregnancy Outcome in Placenta PDFDocument4 pagesObstetric Factors and Pregnancy Outcome in Placenta PDFAl NaifNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- 1 s2.0 S0735109710007795 Main PDFDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0735109710007795 Main PDFshabrinaNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Alexander 2023 My Left KidneyDocument87 pagesAlexander 2023 My Left KidneyStamnumNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Clinical Presentation, Histopathology, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Staging of Soft Tissue Sarcoma - UpToDateDocument36 pagesClinical Presentation, Histopathology, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Staging of Soft Tissue Sarcoma - UpToDateKevin AdrianNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Colorectal Cancer: By:-Vaibhav SwarupDocument18 pagesColorectal Cancer: By:-Vaibhav SwarupOlga GoryachevaNo ratings yet

- Coffee Bean Sign Is Seen In?Document201 pagesCoffee Bean Sign Is Seen In?Ahima SNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- CT Teaching Manual A Systematic ApproachDocument1 pageCT Teaching Manual A Systematic ApproachAul Reyvan AuliaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Raphex Diagnostic Physics 2014 Questions CompressDocument30 pagesRaphex Diagnostic Physics 2014 Questions CompressJuan Antonio Mendoza FloresNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Designing Breakthrough ProductsDocument9 pagesDesigning Breakthrough ProductsSatyaKandukuryNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Vaginal Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and StagingDocument15 pagesVaginal Cancer Early Detection, Diagnosis, and StagingJayashreeNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- William Glasser - Reality TherapyDocument11 pagesWilliam Glasser - Reality TherapyMatej Oven100% (2)

- RADSCIENCESDocument24 pagesRADSCIENCESYael Opeña AlipNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Jurnal Low Back Pain PDFDocument5 pagesJurnal Low Back Pain PDFFikar AxlrosesNo ratings yet

- Radiology of The Urinary SystemDocument78 pagesRadiology of The Urinary Systemapi-19916399No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Ante Saccharomyces CerevisiaeDocument29 pagesAnte Saccharomyces CerevisiaeMichelle Efren-LabantaNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument49 pages1 PDFNurhidayahNo ratings yet

- Differences Between CT Scan and MRIDocument4 pagesDifferences Between CT Scan and MRISujata ThapaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Contrast Use in Cta ApplicationsDocument3 pagesContrast Use in Cta Applicationsmalvina902009No ratings yet

- Bone Scan Update.Document8 pagesBone Scan Update.Dr Jeremy Zapata ReumatologiaNo ratings yet

- The Clinical Impact of Volumetric and Helical CT ImagingDocument12 pagesThe Clinical Impact of Volumetric and Helical CT ImagingAndre ClouatreNo ratings yet

- CT Basic Principles ModifiedDocument55 pagesCT Basic Principles ModifiedRollo TomasiNo ratings yet

- Blunt Abdominal TraumaDocument20 pagesBlunt Abdominal TraumaDeusah EzrahNo ratings yet

- Lung BiopsyDocument8 pagesLung BiopsySiya PatilNo ratings yet

- CT Scan, Mri, Pet ScanDocument5 pagesCT Scan, Mri, Pet ScanAmit MartinNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- 5 Ear Disorders of DogsDocument14 pages5 Ear Disorders of DogsKoleen Lopez ÜNo ratings yet

- Barriers in Radiology.Document3 pagesBarriers in Radiology.Tarun AroraNo ratings yet

- Image Jewelers Diamond EssentialsDocument14 pagesImage Jewelers Diamond EssentialsJewellery Flyers100% (1)

- SIEMENS Coordinación de ProtecciónDocument32 pagesSIEMENS Coordinación de Protecciónarturoelectrica100% (1)

- 2011 Radiology CPT Codes: Cardiac ExamsDocument1 page2011 Radiology CPT Codes: Cardiac Examskarts23No ratings yet

- Sitecore - Media Library - Files.3d Imaging - Shared.7701 3dbrochure UsDocument28 pagesSitecore - Media Library - Files.3d Imaging - Shared.7701 3dbrochure UsandiNo ratings yet

- Pet - 2008Document494 pagesPet - 2008Nathália Cassiano100% (1)

- Lung Cancer ScreeningDocument17 pagesLung Cancer ScreeningNguyen Minh DucNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)