Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History of Yellowstone

History of Yellowstone

Uploaded by

asd 1234Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hippa LettersDocument11 pagesHippa LettersKNOWLEDGE SOURCE100% (9)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Competition LawDocument15 pagesCompetition Lawminakshi tiwariNo ratings yet

- Steel String FunkDocument5 pagesSteel String FunkPoss HumNo ratings yet

- Aba Formal Opinion 497Document9 pagesAba Formal Opinion 497Chris HawkinsNo ratings yet

- GS410-6390 - BA (GeoSwath 4R System User Guide)Document81 pagesGS410-6390 - BA (GeoSwath 4R System User Guide)johan camilo casadiego estevezNo ratings yet

- Scouting Heritage: Merit Badge WorkbookDocument8 pagesScouting Heritage: Merit Badge WorkbookRoger GilbertNo ratings yet

- Samson Vs Corrales TanDocument3 pagesSamson Vs Corrales TanMargarita SisonNo ratings yet

- 3form v. Meridien AccentsDocument7 pages3form v. Meridien AccentsPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Michigan Attorney Discipline Board Order of Suspension For Ralph KimbleDocument2 pagesMichigan Attorney Discipline Board Order of Suspension For Ralph KimbleWWMTNo ratings yet

- BPOC-Resolution Half NakedDocument5 pagesBPOC-Resolution Half NakedCath SanoNo ratings yet

- Employee Travel Expenses SheetDocument5 pagesEmployee Travel Expenses SheetPrashant HartiNo ratings yet

- Viewing Netcool Impact UI Op Views in DASHDocument13 pagesViewing Netcool Impact UI Op Views in DASHNithin GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Service Appeal Against Transfer OrderDocument4 pagesService Appeal Against Transfer Ordermalik shahbaz khanNo ratings yet

- NCE V100R018C10 Command Reference (Restricted) 01-CDocument266 pagesNCE V100R018C10 Command Reference (Restricted) 01-CyugNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881Document12 pagesNegotiable Instruments Act, 1881Prameet PaulNo ratings yet

- Domagoso, IskoDocument8 pagesDomagoso, IskoYanie EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Gabay and Another Against Lloyd (1825) 107 ER 927Document3 pagesGabay and Another Against Lloyd (1825) 107 ER 927Lester LiNo ratings yet

- Digest - in Re BadoyDocument1 pageDigest - in Re Badoyianlayno0% (1)

- Compensation & Reword: Submitted To: Marwa HassonaDocument19 pagesCompensation & Reword: Submitted To: Marwa HassonaMega Pop LockerNo ratings yet

- Was The SWW 'Hitler's War'Document1 pageWas The SWW 'Hitler's War'boiNo ratings yet

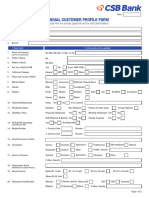

- New CSB Individual Customer Profile FormDocument2 pagesNew CSB Individual Customer Profile Formkrishnajidhu49No ratings yet

- The Truth of YogaDocument6 pagesThe Truth of YogaHugh0% (1)

- Product Leaflet Philips Surge Protection DevicesDocument4 pagesProduct Leaflet Philips Surge Protection DevicesAriel RahmanNo ratings yet

- 04 Assignments Practical Questions NEWDocument21 pages04 Assignments Practical Questions NEWBhupendra MendoleNo ratings yet

- OSH For Public Sector - EditedDocument56 pagesOSH For Public Sector - EditedbiancaNo ratings yet

- Marcelo v. EstacioDocument1 pageMarcelo v. EstacioAbbyr Nul100% (1)

- Makers of JapanDocument182 pagesMakers of JapanNsgNo ratings yet

- SPARK v. Quezon CityDocument4 pagesSPARK v. Quezon CityHogwarts School of Wizardy and WitchcraftNo ratings yet

- Vendor Registration FormDocument10 pagesVendor Registration FormGAURAV SHARMANo ratings yet

- Articles of Incorporation-Stock CorpDocument6 pagesArticles of Incorporation-Stock CorpEarl MagbanuaNo ratings yet

History of Yellowstone

History of Yellowstone

Uploaded by

asd 1234Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History of Yellowstone

History of Yellowstone

Uploaded by

asd 1234Copyright:

Available Formats

HISTORY OF YELLOWSTONE

The park contains the headwaters of the Yellowstone River, from which it takes its historical name.

Near the end of the 18th century, French trappers named the river Roche Jaune, which is probably a

translation of the Hidatsa name Mi tsi a-da-zi ("Yellow Rock River").[16] Later, American trappers

rendered the French name in English as "Yellow Stone". Although it is commonly believed that the

river was named for the yellow rocks seen in the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, the Native

American name source is unclear.[17]

The human history of the park began at least 11,000 years ago when Native Americans began to

hunt and fish in the region. During the construction of the post office in Gardiner, Montana, in the

1950s, an obsidian projectile point of Clovis origin was found that dated from approximately 11,000

years ago.[18] These Paleo-Indians, of the Clovis culture, used the significant amounts of obsidian

found in the park to make cutting tools and weapons. Arrowheads made of Yellowstone obsidian

have been found as far away as the Mississippi Valley, indicating that a regular obsidian trade

existed between local tribes and tribes farther east.[19] By the time white explorers first entered the

region during the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805, they encountered the Nez Perce, Crow, and

Shoshone tribes. While passing through present day Montana, the expedition members heard of the

Yellowstone region to the south, but they did not investigate it.[19]

In 1806, John Colter, a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, left to join a group of fur

trappers. After splitting up with the other trappers in 1807, Colter passed through a portion of what

later became the park, during the winter of 1807–1808. He observed at least one geothermal area in

the northeastern section of the park, near Tower Fall.[20] After surviving wounds he suffered in a

battle with members of the Crow and Blackfoot tribes in 1809, Colter described a place of "fire and

brimstone" that most people dismissed as delirium; the supposedly imaginary place was nicknamed

"Colter's Hell". Over the next 40 years, numerous reports from mountain men and trappers told of

boiling mud, steaming rivers, and petrified trees, yet most of these reports were believed at the time

to be myth.[21]

After an 1856 exploration, mountain man Jim Bridger (also believed to be the first or second

European American to have seen the Great Salt Lake) reported observing boiling springs, spouting

water, and a mountain of glass and yellow rock. These reports were largely ignored because Bridger

was a known "spinner of yarns". In 1859, a U.S. Army Surveyor named Captain William F.

Raynolds embarked on a two-year survey of the northern Rockies. After wintering in Wyoming, in

May 1860, Raynolds and his party—which included naturalist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden and

guide Jim Bridger—attempted to cross the Continental Divide over Two Ocean Plateau from the

Wind River drainage in northwest Wyoming. Heavy spring snows prevented their passage, but had

they been able to traverse the divide, the party would have been the first organized survey to enter

the Yellowstone region.[22] The American Civil War hampered further organized explorations until

the late 1860s.[23]

Ferdinand V. Hayden (1829–1887) American geologist who convinced Congress to make

Yellowstone a national park in 1872.

The first detailed expedition to the Yellowstone area was the Cook–Folsom–Peterson Expedition of

1869, which consisted of three privately funded explorers. The Folsom party followed the

Yellowstone River to Yellowstone Lake.[24] The members of the Folsom party kept a journal and

based on the information it reported, a party of Montana residents organized the Washburn–

Langford–Doane Expedition in 1870. It was headed by the surveyor-general of Montana Henry

Washburn, and included Nathaniel P. Langford (who later became known as "National Park"

Langford) and a U.S. Army detachment commanded by Lt. Gustavus Doane.

The expedition spent about a month exploring the region, collecting specimens and naming sites of

interest. A Montana writer and lawyer named Cornelius Hedges, who had been a member of the

Washburn expedition, proposed that the region should be set aside and protected as a national park;

he wrote detailed articles about his observations for the Helena Herald newspaper between 1870

and 1871. Hedges essentially restated comments made in October 1865 by acting Montana

Territorial Governor Thomas Francis Meagher, who had previously commented that the region

should be protected.[25] Others made similar suggestions. In an 1871 letter from Jay Cooke to

Ferdinand V. Hayden, Cooke wrote that his friend, Congressman William D. Kelley had also

suggested "Congress pass a bill reserving the Great Geyser Basin as a public park forever"

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hippa LettersDocument11 pagesHippa LettersKNOWLEDGE SOURCE100% (9)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Competition LawDocument15 pagesCompetition Lawminakshi tiwariNo ratings yet

- Steel String FunkDocument5 pagesSteel String FunkPoss HumNo ratings yet

- Aba Formal Opinion 497Document9 pagesAba Formal Opinion 497Chris HawkinsNo ratings yet

- GS410-6390 - BA (GeoSwath 4R System User Guide)Document81 pagesGS410-6390 - BA (GeoSwath 4R System User Guide)johan camilo casadiego estevezNo ratings yet

- Scouting Heritage: Merit Badge WorkbookDocument8 pagesScouting Heritage: Merit Badge WorkbookRoger GilbertNo ratings yet

- Samson Vs Corrales TanDocument3 pagesSamson Vs Corrales TanMargarita SisonNo ratings yet

- 3form v. Meridien AccentsDocument7 pages3form v. Meridien AccentsPriorSmartNo ratings yet

- Michigan Attorney Discipline Board Order of Suspension For Ralph KimbleDocument2 pagesMichigan Attorney Discipline Board Order of Suspension For Ralph KimbleWWMTNo ratings yet

- BPOC-Resolution Half NakedDocument5 pagesBPOC-Resolution Half NakedCath SanoNo ratings yet

- Employee Travel Expenses SheetDocument5 pagesEmployee Travel Expenses SheetPrashant HartiNo ratings yet

- Viewing Netcool Impact UI Op Views in DASHDocument13 pagesViewing Netcool Impact UI Op Views in DASHNithin GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Service Appeal Against Transfer OrderDocument4 pagesService Appeal Against Transfer Ordermalik shahbaz khanNo ratings yet

- NCE V100R018C10 Command Reference (Restricted) 01-CDocument266 pagesNCE V100R018C10 Command Reference (Restricted) 01-CyugNo ratings yet

- Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881Document12 pagesNegotiable Instruments Act, 1881Prameet PaulNo ratings yet

- Domagoso, IskoDocument8 pagesDomagoso, IskoYanie EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Gabay and Another Against Lloyd (1825) 107 ER 927Document3 pagesGabay and Another Against Lloyd (1825) 107 ER 927Lester LiNo ratings yet

- Digest - in Re BadoyDocument1 pageDigest - in Re Badoyianlayno0% (1)

- Compensation & Reword: Submitted To: Marwa HassonaDocument19 pagesCompensation & Reword: Submitted To: Marwa HassonaMega Pop LockerNo ratings yet

- Was The SWW 'Hitler's War'Document1 pageWas The SWW 'Hitler's War'boiNo ratings yet

- New CSB Individual Customer Profile FormDocument2 pagesNew CSB Individual Customer Profile Formkrishnajidhu49No ratings yet

- The Truth of YogaDocument6 pagesThe Truth of YogaHugh0% (1)

- Product Leaflet Philips Surge Protection DevicesDocument4 pagesProduct Leaflet Philips Surge Protection DevicesAriel RahmanNo ratings yet

- 04 Assignments Practical Questions NEWDocument21 pages04 Assignments Practical Questions NEWBhupendra MendoleNo ratings yet

- OSH For Public Sector - EditedDocument56 pagesOSH For Public Sector - EditedbiancaNo ratings yet

- Marcelo v. EstacioDocument1 pageMarcelo v. EstacioAbbyr Nul100% (1)

- Makers of JapanDocument182 pagesMakers of JapanNsgNo ratings yet

- SPARK v. Quezon CityDocument4 pagesSPARK v. Quezon CityHogwarts School of Wizardy and WitchcraftNo ratings yet

- Vendor Registration FormDocument10 pagesVendor Registration FormGAURAV SHARMANo ratings yet

- Articles of Incorporation-Stock CorpDocument6 pagesArticles of Incorporation-Stock CorpEarl MagbanuaNo ratings yet